Abstract

Mental health difficulties in university students are an increasing concern, especially after the COVID-19 global crisis. This study used a cross-sectional design to analyze the effect of psychological factors on students’ psychological well-being. Participants were 190 university students enrolled in undergraduate or graduate programs at a public university. Based on previous research and grounded theoretical models, a conceptual model was proposed to analyze the influence of affect states/experiences (emotion regulation difficulties, anxiety and depression, perceived stress, self-compassion, gratitude, and satisfaction with life) on psychological well-being, including the indirect effect of emotions (negative emotions, positive activation emotions, self-efficacy emotions, prosocial emotions, and serenity emotions), using a path analysis. Multigroup analyses were also performed to test the moderating effect of gender and education level. Findings indicated that self-efficacy emotions had an indirect effect on the relationship between anxiety and depression, self-compassion, and psychological well-being. Both prosocial and self-efficacy emotions indirectly impacted the relationship between gratitude, satisfaction with life, and psychological well-being. Being a female and a bachelor student played a moderating role in the final model. The findings suggest that psychological interventions focused on self-efficacy and prosocial emotions are needed to increase psychological well-being in university students.

1. Introduction

The transition to college life can be emotionally demanding as students must adapt to a new environment, often dealing with novel and intense academic pressures, increased responsibilities, and changes in their social lives (Asif et al., 2020). These challenges may contribute to the development of psychological disorders and reduced well-being among university students. Mental health difficulties are increasingly prevalent in this population (Asif et al., 2020; Campbell et al., 2022), with university students suffering from stress, anxiety, and depression (Karakasidou et al., 2023), especially after the COVID-19 restrictions (Li et al., 2020). Currently, the growing number of university students diagnosed with mental health conditions represents a health and societal concern, with substantial implications for students’ academic performance and psychological well-being (PWB) (Campbell et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020).

PWB is a complex and multidimensional construct described as optimal psychological functioning and human experience. PWB includes feelings of overall happiness, satisfaction with life, fulfillment, and mental and emotional health which may be described as hedonic (e.g., happiness, enjoyment) or eudaimonic (e.g., meaning, autonomy) well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2001). The interest in PWB in higher education has grown exponentially in the last decade, mainly because young adults are more prone to report emotional problems that are known to negatively impact their well-being, making university students particularly vulnerable to mental disorders (Solmi et al., 2022). Moreover, the global health crisis caused by COVID-19 affected, in particular, young adults, inflicting unpredictable stress resulting from prolonged confinement measures and restrictions on social interaction (Aristovnik et al., 2020).

Affect states/experiences are feelings experienced in reaction to internal or external stimuli that may range in valence (positive or negative) and intensity, impacting PWB (Gross et al., 2019). Previous research showed that emotion regulation (e.g., Renati et al., 2023), self-compassion (e.g., Neff, 2023), gratitude (e.g., Martinez et al., 2022), anxiety and depression (e.g., Karakasidou et al., 2023), and perceived stress (e.g., Asif et al., 2020) are associated with university students’ PWB.

Emotion regulation strategies, i.e., one’s ability to adaptively modulate emotional responses and cope with frustrating experiences, have been positively associated with PWB (Renati et al., 2023). In contrast, difficulties in emotion regulation may lead to distress and decreased well-being (Gross et al., 2019). The literature consistently shows that emotion regulation positively affects PWB, enabling students to manage stress effectively, navigate interpersonal relationships, and adapt to the demands of the academic environment (e.g., Renati et al., 2023). A study involving psychology undergraduates from the southern United States (Rufino et al., 2022) showed that individuals exhibiting greater emotion dysregulation reported poorer mental health and reduced well-being during the pandemic.

Self-compassion is also linked to well-being (Neff, 2023), significantly predicting greater PWB (Karakasidou et al., 2023; Kotera et al., 2019). Self-compassion involves treating oneself with kindness, empathy, understanding, and acceptance in times of struggle or emotional suffering (Neff, 2023). Students reporting higher levels of self-compassion tend to cope more effectively with stress, depression and anxiety, are less critical of themselves, show more forgiveness towards their imperfections, and report higher PWB (Póka et al., 2024; Neff, 2023). Existing research also indicates that self-compassion reduces psychopathology by decreasing negative thoughts and emotions, and enhancing emotion regulation skills (Neff, 2023).

Previous studies have shown the predictive role of gratitude in promoting PWB (Kardas et al., 2019; Măirean et al., 2019; Martinez et al., 2022; Portocarrero et al., 2020). Experiencing gratitude involves appreciating the positive aspects of one’s life, experiences, and relationships. Gratitude also has the potential to foster optimism, reduce stress levels, enhance overall life satisfaction, and promote appreciation for the importance of a college education (Harlianty et al., 2022; Măirean et al., 2019; Portocarrero et al., 2020). A cross-sectional study conducted in Colombia with university students during the COVID-19 lockdown (Martinez et al., 2022) indicated that optimism and gratitude mitigated the pandemic’s negative impact, being positively correlated with well-being.

As expected, anxiety, depression, and perceived stress increased in university students after the pandemic outbreak, negatively affecting their overall well-being (Asif et al., 2020; Campbell et al., 2022; Karakasidou et al., 2023; Martinez et al., 2022) and academic performance (Li et al., 2020; Martinez et al., 2022; Mehmood & Shaukat, 2014). A scoping review of 90 original studies reported that 29.1% of university students reported anxiety symptoms, and 23.2% experienced depression symptoms, highlighting the adverse effects of COVID-19 on their PWB (Ebrahim et al., 2022).

Satisfaction with life, defined as an individual’s overall life assessment based on a positive evaluation of one’s experiences (Diener, 1984), is often used as an indicator of well-being (Portocarrero et al., 2020). According to previous studies, higher satisfaction with life is linked to greater PWB and lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress in university students (Mehmood & Shaukat, 2014; Ojha & Kumar, 2017), particularly after the coronavirus outbreak (e.g., Clair et al., 2021).

More recently, positive and negative emotions have been suggested as potential mediators of PWB. A study by Hendriks et al. (2021) found that positive emotions were a potential mediator of a positive psychology intervention aimed at increasing well-being. Zhao et al. (2019) also found that higher emotional intelligence was associated with lower levels of negative emotions, which contributed to improved PWB, suggesting that individuals with greater emotional intelligence were better equipped to manage negative emotions, leading to enhanced overall well-being.

The circumplex model of affect (Russell, 1980) states that affect experiences are not independent of one another since they are based on pleasure and arousal components. The empirical evidence of the model showed a sad versus happy affect component and a relaxed versus tense component, which was tested in undergraduate students.

Difficulties in emotion regulation, anxiety, depression, and stress are the most frequent reactions reported by university students, with a significant impact on PWB (Asif et al., 2020; Campbell et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020; Karakasidou et al., 2023). Stimulating emotions such as self-compassion and gratitude also predicted PWB in this population (Karakasidou et al., 2023; Kardas et al., 2019), while satisfaction with life represents a widely recognized predictor of well-being (Portocarrero et al., 2020). Therefore, in our proposed model, satisfaction with life (happy quadrant), perceived stress, anxiety, and depression (sad quadrant), gratitude as mood and self-compassion (relaxed quadrant), and difficulties in emotion regulation (tense quadrant) were selected to see how these affect states/experiences could predict wellbeing in college students.

Beyond the circumplex model of affect, the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2004) suggests that the capacity to experience positive emotions, contrary to negative emotions, may be a fundamental human resource central to one’s well-being. Empirical evidence supporting the theory (Hendriks et al., 2021) found that positive emotions mediated the relationship between positive affect experiences (e.g., writing a gratitude letter, performing acts of kindness, practicing forgiveness) and mental well-being.

Moreira and Gamboa (2016) also created a five-dimensional emotional model from an extensive list of emotion words in Portuguese, which was empirically tested in college students. The model offers a comprehensive assessment of positive and negative emotions, making it particularly relevant to educational research. According to Moreira and Gamboa, the model includes negative emotions (unpleasant feelings such as sadness, fear); positive emotions (uplifting and energizing emotions such as passionate or daring); self-efficacy emotions (emotions related to the belief in one’s ability to accomplish tasks or goals); prosocial emotions (emotions related to social connectedness, purpose and meaning in life, including feelings of empathy, connection, kindness, and a desire to help others); and serenity emotions (sense of calm, tranquility, harmony, and inner peace).

The impact of sex on well-being has not yielded consistent outcomes (e.g., Ferguson & Gunnell, 2016). Such differences seem to vary according to social factors influencing mental health, with women scoring higher on specific dimensions of well-being (e.g., positive relations with others), and men on others (e.g., self-acceptance and autonomy) (Ahrens & Ryff, 2006). Similarly, findings on the impact of education on well-being have been contradictory. Some studies report a positive association between high levels of education and well-being or life satisfaction (Nikolaev, 2018). In contrast, other studies indicated a negative relationship between education and PWB, probably because higher levels of education may be related to higher expectations that are more challenging to meet (Clark & Oswald, 1996). Given those contradictory findings, it is essential to further investigate the roles of gender and education level in students’ PWB, particularly post-COVID-19 outbreak.

Despite the extensive body of research addressing the impact of different affect states/experiences on PWB among university students, the indirect effect of positive and negative emotions on PWB needs more exploration, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in a decline in students’ PWB, with a significant negative impact on mental health (Aristovnik et al., 2020; Ebrahim et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020).

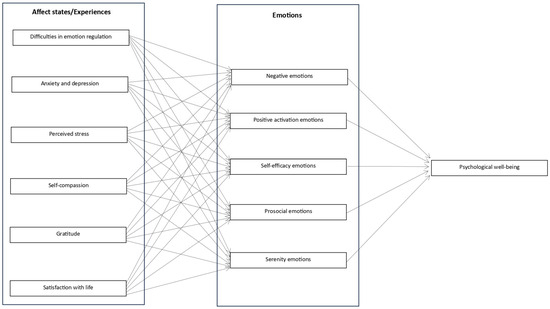

Based on previous research and the three theoretical models/theories previously described, we proposed a model (Figure 1), and hypothesized that positive and negative emotions might play an indirect role in the relationship between affect states/experiences and well-being in college students (Hypothesis 1). Our primary goal was to explore how affect states/experiences predicted PWB, going beyond the absence of psychopathology. Considering the inconsistencies in recent studies regarding the role of gender and education on students’ PWB, we further hypothesized that these two factors will moderate the aforementioned relationships (Hypothesis 2).

Figure 1.

The proposed conceptual model.

From a heuristic point of view, this knowledge may inform the development of targeted interventions focused on preventing poor mental health and, most importantly, help ensure that students at risk receive appropriate professional support.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This cross-sectional study used a convenience sample of university students. Questionnaires were administered online through the Qualtrics platform when hybrid learning prevailed in Portuguese universities.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The study received ethical approval by the Ethics Committee for Research in Social and Human Sciences of a major university in Northern Portugal (Reference: CEICSH 021_2019). All participants provided written informed consent, following the Helsinki Declaration and the Oviedo Convention.

2.3. Participants

Participants were recruited through the institutional university email and a credit platform system (for psychology students). Students who were formerly enrolled at the university, and had attended classes during the two semesters of data collection were considered eligible to participate. Those who agreed to participate signed a written informed consent before completing the self-report measures. Questionnaires took approximately 20 min to complete. If students desired to take a break during the process, they could use a designated link to resume where they left off. To ensure confidentiality, all responses were collected anonymously. A total of 190 students participated in the study. Table 1 summarizes the participants’ characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, data collection occurred between April 2021 and December 2022. Since Qualtrics only saves complete survey responses, there was no missing data.

2.4. Instruments

Sociodemographic Questionnaire. This questionnaire was created by the authors for the present study, and evaluated sociodemographic variables such as gender, age, marital status, education, academic course, and physical activity.

Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWS; Novo et al., 1997). PWS measures different aspects of well-being through 18 items divided into six subscales: autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. All items are answered on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). This study used the PWS total score, with higher scores reflecting greater PWB. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the original PWS subscales ranged from 0.33 to 0.56, which is acceptable given the limited number of items per subscale (Taber, 2018). In the Portuguese version, Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales ranged from 0.74 to 0.86, while for the total scale, it was 0.93. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was 0.84.

Affective State Inventory-Reduced (ASI-R; Moreira & Gamboa, 2016). This questionnaire measures emotional states through 19 items distributed across five subscales: negative emotions, positive activation emotions, self-efficacy emotions, prosocial emotions, and serenity emotions. Items are evaluated using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very little or none at all) to 5 (extremely), with higher scores indicating a higher emotional state in the specific domain assessed. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the subscales of the Portuguese version ranged from 0.63 to 0.87, whereas in the present study, they ranged from 0.81 to 0.90.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Coutinho et al., 2010). This is a 36-item questionnaire designed to assess emotion dysregulation across six domains: nonacceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, impulse control difficulties, limited access to emotional regulation strategies, lack of emotional awareness, and lack of emotional clarity. Participants are asked to rate items using a five-point Likert scale of 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), and higher scores indicate greater difficulties in regulating emotions. Cronbach’s alphas for the total scores were 0.93 in the original version and 0.92 in the Portuguese version. The current study used the total scale, yielding a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.96.

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Castilho et al., 2015). SCS measures individual levels of self-compassion through 26 items divided into six subscales: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification. Each question is answered on a five-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), and higher scores correspond to higher levels of self-compassion. Cronbach’s alpha for the original scale was 0.93, while in the Portuguese version it was 0.89. Only the total scale was used in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.69.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2007). HADS consists of 14 items designed to assess symptoms of anxiety and depression. Respondents are asked to rate how they felt during the past week, using a four-point Likert scale (0-3), with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. In the original validation study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.90 for the anxiety subscale and 0.80 for the depression subscale. For the Portuguese version, internal consistency values were 0.76 and 0.81 for the anxiety and depression subscales, respectively. The present study used the total scale, presenting a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Trigo et al., 2010). PSS measures the degree to which life situations are perceived as stressful. This scale includes 10 items that are answered on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very frequently), and higher scores indicate higher perceived stress. Cronbach’s alpha for the original scale was 0.78, while for the Portuguese version it was 0.87. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6; Neto, 2007). GQ-6 includes six items to assess the tendency to experience gratitude in daily life. Items use a five-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), and higher scores reflect higher levels of gratitude. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in the original version was 0.82, while the Portuguese version showed an alpha of 0.75. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78.

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SwL; Simões, 1992). This instrument measures overall contentment with one’s life using five items. Questions are answered on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree), with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction with life. Cronbach’s alphas for the original version, the Portuguese version, and the present study were 0.87, 0.77, and 0.85, respectively.

2.5. Data Analysis

Given that the assumptions for parametric statistics were met, Pearson correlations were used to analyze the relationships among all variables. Only independent variables showing moderate to high correlations with PWB or emotions (r > 0.30, p < 0.05) were included in the path analysis model (Field, 2009). A power analysis was performed with power set at 0.80, a significance level of 5%, a medium effect size, and 11 independent variables (emotional regulation difficulties, anxiety and depression, perceived stress, self-compassion, gratitude, satisfaction with life, and five emotions), requiring a sample size of 131 participants (Soper, 2019). The corollaries to perform a path analysis were present. We assessed the data for key assumptions, including normality, linearity, uncorrelated residuals, and multicollinearity. Univariate normality was evaluated through skewness and kurtosis values, all within acceptable ranges (between −2 and +2), suggesting that normality assumptions were reasonably met. Tolerance values were greater than 0.10, the VIF values were below 2, the eigenvalues were not close to 0, and the condition index values indicated non-collinearity (Marcoulides & Raykov, 2019), ensuring the stability and reliability of the model estimates.

To assess the adequacy of the path analysis model, goodness-of-fit indices were calculated, with a chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df) < 2, goodness of fit index (GFI) ≥ 0.95, comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ 0.95, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) ≥ 0.95, root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) < 0.07, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) < 0.08, indicating a good fit (Hair et al., 2010). Indirect effects were tested using 5000 bootstrap samples with a 95% confidence interval. Additionally, multigroup analyses were conducted to test the moderating effect of gender (male versus female) and education level (attending a bachelor’s versus master’s degree). All results are reported using unstandardized regression coefficients.

The analyses were conducted using SPSS Software (version 28.0) and SPSS AMOS (version 28.0).

3. Results

3.1. Path Analysis

The correlation between all the variables and PWB is described in Table 2. Given that positive activation emotions (ASI-R subscale) did not correlate significantly with PWB, the initial path analysis model did not include the indirect effect of this emotion.

Table 2.

Correlations between all variables.

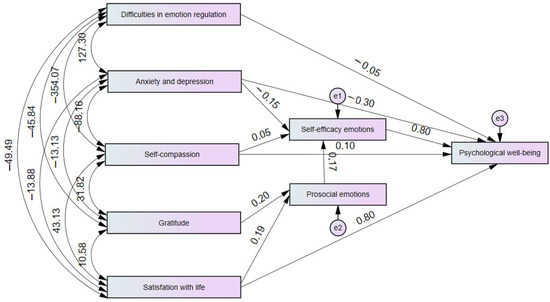

The estimated values of the fit indices in the initial model indicated that the RMSEA index was not acceptable, and several pathways (covariances) between the variables were not significant, undermining the adequacy of the model’s global fit: χ2/DF = 2.31, GFI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.08 [0.03, 0.14]; SRMR = 0.02. Subsequently, several pathways were explored according to the modification indices, the significance of the path coefficients, and the final model adjustment. Specifically, the non-significant paths (p < 0.05) were removed. After their removal, five modification indexes remained and were taken into consideration, resulting in the addition of direct relationships between the independent variables (emotion regulation, anxiety and depression, self-compassion, and satisfaction with life) and PWB, as well as between prosocial and efficacy emotions (Figure 2). The adjusted model revealed a strong model fit: χ2/DF = 1.09, GFI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.02 [0.00, 0.09]; SRMR = 0.03.

Figure 2.

The indirect effect of emotions (self-efficacy and prosocial emotions) in the relationship between emotion regulation difficulties, anxiety and depression, self-compassion, gratitude, satisfaction with life, and psychological well-being. Note: Values in the independent variables indicate the covariances between the variables, while values in the direct and indirect paths are unstandardized regression coefficients (β).

The results of the final adjusted model indicated that emotion regulation was negatively associated with PWB (β = −0.05, p = 0.031). Self-compassion was positively associated with self-efficacy emotions (β = 0.05, p < 0.001) and PWB (β = 0.10, p = 0.002), while anxiety and depression showed a negative association with self-efficacy emotions (β = −0.15, p < 0.001) and PWB (β = −0.30, p < 0.001). Gratitude was positively associated with prosocial emotions (β = 0.20, p = 0.001), and satisfaction with life was positively associated with prosocial emotions (β = 0.19, p = 0.001) and PWB (β = 0.80, p < 0.001).

The indirect effects presented in Table 3 show that self-efficacy emotions had an indirect effect in the relationships between self-compassion and PWB (β = 0.04, p < 0.001), and between anxiety and depression and PWB (β = −0.12, p < 0.001). Both prosocial and self-efficacy emotions had an indirect effect in the relationships between gratitude and PWB (β = 0.03, p = 0.006), and between satisfaction with life and PWB (β = 0.03, p = 0.006) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Unstandardized indirect effects in the final adjusted model.

3.2. The Moderating Role of Gender and Education Level

Analysis of the moderating effect of gender indicated a significant difference between the unconstrained adjusted model and the fully constrained model (Δ χ2 (10) = 19.26, p = 0.037), suggesting that gender significantly moderated the hypothesized relationships in the final model. Specifically, only male participants showed a significant relationship between emotional regulation and PWB (β = −0.19, p = 0.01). Also, significant relationships between anxiety and depression and PWB (β = −0.36, p < 0.001), gratitude and prosocial emotions (β = 0.22, p = 0.002), and self-efficacy emotions and PWB (β = 0.80, p < 0.001) were observed only among female participants. Regarding indirect effects, significant paths were found exclusively in female participants. Self-efficacy emotions had an indirect effect in the relationship between anxiety and depression and PWB (β = −0.12, p < 0.001), as well as between self-compassion and PWB (β = 0.04, p = 0.001). Additionally, both prosocial and self-efficacy emotions had an indirect effect on the relationships between gratitude and PWB (β = 0.03, p = 0.019), and between satisfaction with life and PWB (β = 0.02, p = 0.021).

In terms of the moderating effect of education level (master’s versus bachelor’s degree), results indicated a significant difference between the unconstrained adjusted model and the fully constrained model (Δ χ2 (10) = 18.94; p = 0.041), suggesting that education level significantly moderated the hypothesized relationships in the final model. Specifically, gratitude was significantly associated with prosocial emotions only among master’s students (β = 0.41, p < 0.001). Also, significant relationships between anxiety and depression and self-efficacy emotions (β = −0.17, p < 0.001), satisfaction with life and prosocial emotions (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), and prosocial and self-efficacy emotions (β = 0.16, p = 0.005) emerged solely among bachelor students. Regarding indirect effects, significant paths were observed exclusively among bachelor students. Self-efficacy emotions exhibited an indirect effect in the relationships between anxiety and depression and PWB (β = −0.15, p < 0.001) and between self-compassion and PWB (β = 0.04, p = 0.002). Furthermore, both prosocial and self-efficacy emotions had an indirect effect in the relationship between satisfaction with life and PWB (β = 0.03, p = 0.009) only in bachelor students.

4. Discussion

The main goal of this study was to test a model focused on the indirect effect of emotions in the relationships between affect states/experiences and PWB, as well as the moderating role of gender and students’ education level.

Positive activation emotions (i.e., feeling audacious, daring) did not correlate significantly with PWB, which may reflect the limited opportunities during the pandemic to experience high-arousal, energizing emotions (e.g., fewer social events, campus activities). Interestingly, positive activation emotions did not correlate with negative emotions or most affect states. This pattern may suggest that, in the unique context of the pandemic, high-arousal positive emotions became somewhat disconnected from students’ broader emotional and psychological functioning. Instead, students’ well-being might have relied more on low-arousal positive emotions, such as prosocial and self-efficacy emotions, which could be sustained through online interactions, academic engagement, and supportive relationships, even during periods of social restriction.

The final adjusted model confirmed the indirect effect of only two positive emotions (self-efficacy and prosocial emotions) on PWB. Although negative emotions were expected to negatively impact PWB, this effect was not observed. This finding may suggest that negative emotions were not central to students’ PWB in the aftermath of the pandemic or that their coping strategies buffered the impact of these emotions. Similarly, serenity emotions (e.g., feeling calm, peaceful) might not have played a protective role, as the COVID-19 context may have demanded more active coping strategies rather than passive calm (Akeman et al., 2022). Furthermore, previous research has shown that under stressful situations, women report lower self-efficacy emotions (Cuadrado et al., 2022) and are more likely to engage in prosocial behaviors (Taylor et al., 2000), which could help explain why, in our predominantly female sample, prosocial emotions and self-efficacy emotions emerged as significant correlates of PWB. Future research is needed to further clarify the complex role of different emotions in shaping university students’ PWB, particularly during periods of crisis.

The results showed that satisfaction with life directly influenced PWB, corroborating the extensive literature that identifies satisfaction with life as a key contributor to PWB, in the general population (Portocarrero et al., 2020), and specifically in university students (Kardas et al., 2019). Difficulties in emotion regulation also had a significant, direct negative effect on PWB as expected, given that emotional regulation has a critical role in PWB (Renati et al., 2023). According to several studies, emotional regulation strategies are positively associated with PWB and may lead to positive changes in individuals’ well-being (e.g., Rahmania et al., 2020), while difficulties in emotion regulation are associated with worse PWB (Fernández-Fernández et al., 2020). Therefore, using maladaptive emotional strategies seems to compromise university students’ PWB, suggesting that promoting effective self-regulation strategies is paramount in this population.

Anxiety and depression had a significant negative direct effect on PWB, consistent with evidence showing that psychological morbidity adversely affects well-being (Asif et al., 2020; Gallagher et al., 2021; Karakasidou et al., 2023; Martinez et al., 2022). Furthermore, considering the high prevalence of mental health issues within the university context (Asif et al., 2020; Campbell et al., 2022; Solmi et al., 2022), the adverse effect of psychological morbidity on PWB, found in this study, is not surprising. The direct positive influence of self-compassion on PWB makes theoretical sense, as self-compassion is a significant predictor of PWB (Kotera et al., 2019). Tran et al. (2024) found that high self-compassion helped undergraduate students cope with the adverse psychological effects of COVID-19 and predicted positive PWB. Overall, the results of the present study showed that satisfaction with life, emotion regulation, anxiety and depression, and self-compassion had a direct impact on university students’ PWB.

Both prosocial and self-efficacy emotions had an indirect effect on the relationship between gratitude, satisfaction with life, and PWB. Individuals who experience gratitude and feel satisfied with life are more likely to develop positive interpersonal emotions, such as kindness and empathy (Armenta et al., 2017; Fredrickson, 2004). These prosocial emotions, in turn, foster emotions characterized by confidence and determination (Caprara & Steca, 2007; Moreira & Gamboa, 2016). This pattern is consistent with the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2004), which suggests that positive emotions expand individuals’ thought-action repertoires and help build lasting personal resources. Emotions also facilitate adaptive regulation regarding thoughts, affect, and actions (Gross et al., 2019; Ojha & Kumar, 2017), contributing to greater PWB (Gross et al., 2019). However, it should be noted that the indirect effect of prosocial emotions happened through self-efficacy emotions rather than directly, thereby highlighting the role of self-efficacy emotions in the model.

Self-efficacy emotions were found to have an indirect effect on the relationship between self-compassion, anxiety and depression, and PWB. Self-compassion may act as an emotional regulation strategy, where negative feelings and thoughts are not avoided, providing an understanding of the situation (Diedrich et al., 2014; Neff, 2023). In other words, negative emotions may be converted into positive emotional states, providing a positive perspective of the event (Diedrich et al., 2014). By attenuating individuals’ negative reactions to adverse situations, self-compassion enhances resilience, thereby playing an essential role in promoting self-efficacy to deal with stressful or challenging demands (Liao et al., 2021). Furthermore, self-compassion was found to act as an effective protective factor for positive psychological functioning among university students in the context of COVID-19 (Karakasidou et al., 2023; Tran et al., 2024), with several studies indicating that self-compassionate individuals tend to express more happiness, more satisfaction with life, lower negative affect, and lower psychological morbidity when compared to less self-compassionate individuals (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012). Individuals with higher levels of anxiety and depression believe less in their ability to accomplish goals (i.e., self-efficacy emotions) (Shek et al., 2023), which, as expected, negatively affects their PWB (Gallagher et al., 2021). Given that the final model confirmed the indirect effect of only two emotions, and emotion regulation difficulties were directly linked to PWB, the initial conceptual model was not fully supported. Thus, H1 was partially accepted.

According to the results, gender had a moderating effect in the final model, with female students showing a significant relationship between anxiety and depression, and PWB, both directly and indirectly via self-efficacy emotions. Being a female is a well-documented predictor of psychological distress (Stallman, 2010), and female students in particular are more likely to experience psychological symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression, somatization) (Beatens et al., 2022). Research on gender differences in academic self-efficacy suggests that male students generally report slightly higher levels of self-efficacy (Huang, 2013). However, women typically report higher self-efficacy emotions in social domains (Pérez et al., 2015), which may help explain why, among female students, self-efficacy had an indirect effect in the relationship between anxiety and depression, and PWB. The indirect effect of self-efficacy emotions in the association between self-compassion and PWB was also significant in female students, despite men exhibiting higher levels of self-compassion than women (Póka et al., 2024). Future research is warranted to further explore gender differences in the relationship between self-compassion, self-efficacy, and PWB.

Prosocial and self-efficacy emotions only showed an indirect effect in the relationship between gratitude, satisfaction with life, and PWB in female students. Previous research has consistently shown that women report more satisfaction with life (Joshanloo & Jovanović, 2020) and express more positive affect and gratitude than men, being more aware of their emotional experiences (Stallman, 2010). Therefore, expressing positive affect (e.g., kindness) may enhance a person’s social network and, consequently, PWB (Stallman, 2010). In male students, PWB was predicted by difficulties in emotion regulation, which is in accordance with empirical findings showing men as more likely to resort to emotion suppression and impulse control, reporting more problems with emotional acceptance (Kaur et al., 2022) compared to women. Overall, the indirect effect of emotions was significant only in female students, possibly due to the significant number of women in this study (85.5%).

The students’ education level (bachelor versus master) also had a moderating effect in the adjusted model. Specifically, the indirect effect of self-efficacy emotions in the relationship between anxiety and depression, self-compassion, and PWB was significant only in bachelor students. Based on existing research, during the COVID-19 pandemic, bachelor’s students reported lower levels of PWB than master’s students (Beatens et al., 2022). Also, being in the first and second academic years was significantly associated with more anxiety and depression among bachelor’s students, particularly first-year students, who are more prone to developing psychological symptoms such as depression, and report more feelings of loneliness (Beatens et al., 2022). Such symptoms may result from adaptation to a new environment (e.g., university), often characterized by increased responsibilities, academic pressure, and changes in social relationships (Asif et al., 2020). In addition, undergraduate students, who report higher anxiety and depressive symptoms, often report lower self-efficacy emotions (Shek et al., 2023). Self-compassion, which involves adopting a self-caring attitude in times of adversity, may enhance an individual’s ability to cope with difficult times (Neff, 2023). Thus, it makes theoretical sense that self-compassionate students report more self-efficacy emotions and PWB, especially bachelor’s students, as they face more challenges as a result of the adaptation to the university environment, compared to master’s students who have been in the university for an extended period, and have already finished a university degree (Asif et al., 2020; Campbell et al., 2022).

The indirect effect of prosocial and self-efficacy emotions in the relationship between satisfaction with life and PWB was significant only in bachelor students. Satisfaction with life is linked to prosocial behaviors (e.g., altruistic behaviors, helping others) (Mehmood & Shaukat, 2014; Ojha & Kumar, 2017). Moreover, there is a relationship between prosocial and self-efficacy emotions since the belief in one’s ability to achieve goals and overcome challenges may be influenced by social interaction, providing emotional support, and a positive view of one’s abilities and skills (Caprara & Steca, 2007). Likewise, Mehmood and Shaukat (2014) suggested that positive social relationships associated with prosocial emotions and academic achievements associated with self-efficacy emotions were key contributors to satisfaction with life in university students. Prosocial and self-efficacy emotions may be particularly relevant for bachelor’s students, since the integration into the university depends on the student’s social support network and academic self-efficacy (Erzen & Ozabaci, 2023).

The relationship between gratitude and prosocial emotions was significant only in master’s students. There is evidence that gratitude promotes prosocial behaviors and emotions (e.g., helping others, cooperation), contributing to healthy relationships (Oguni & Otake, 2020), and enhancing satisfaction with life (Harlianty et al., 2022; Măirean et al., 2019; Portocarrero et al., 2020). Given that master’s students have spent at least three years at university, it is reasonable to expect that they have already adjusted and feel integrated into the academic environment and, as a result, develop more gratitude and feel more socially supported compared to younger students. Overall, findings support the moderating effect of gender and students’ education level, confirming H2.

The present study has some limitations that should be addressed. The sample was recruited from a single university through convenience sampling, being overrepresented by female psychology students, which limits the generalization of the findings. However, it is worth noting that this overrepresentation reflects the demographic characteristics of the population from which the sample was drawn, as women constitute the majority in university psychology programs. Also, female psychology students may be more aware of their emotions than the general population, so findings must be interpreted cautiously. To mitigate potential biases, we conducted subgroup analyses examining gender and education level as moderators in our model, which allowed us to better understand how these factors influenced PWB. Data collection occurred right after the COVID-19 outbreak, so findings should be interpreted considering this specific context. Additionally, the cross-sectional design does limit the scope of the findings. Finally, the exclusive use of self-report measures to measure PWB is also a limitation.

Future research should aim to recruit more balanced and diverse university student samples to confirm the findings’ robustness and generalizability. Longitudinal studies focused on the impact of the affect states/experiences on PWB, as students progress through their academic journey, would also be important, including whether academic performance moderates the relationship between those affect experiences and PWB. Future studies should also include the moderator role of gender and education level, as students pursue their studies, which would further enhance our understanding and help design interventions adapted to students’ needs.

5. Conclusions

The university is a privileged context that promotes the well-being of young adults. As more students from minority groups and vulnerable backgrounds now attend university, they may experience more challenges in their transition to adulthood. Therefore, universities should give students the psychological resources they need to attain their personal, social, and academic goals. Interventions that promote positive emotions are paramount to increase students’ PWB and should be made accessible to students before and, particularly, during the first years of university. Psychological assessment could also be used to identify students who may be more at risk for lower PWB to provide them with the support they need.

According to the results, positive affect states/experiences (e.g., self-compassion, gratitude, emotion regulation skills) could be taught to students and integrated into their academic curricula to foster their PWB. Such practices could be embedded into students’ academic development through community projects. Service-Learning (SL) activities, an educational approach that applies academic knowledge to real-world community needs, could provide a practical “lab” for students to practice positive affect experiences and develop positive emotions, all while earning curriculum credits toward graduation.

SL opportunities could be offered through internships designed to increase positive emotions as part of the academic curriculum. Students would have the option to select which internships they would like to pursue, and would earn credit for these activities. Professors could assess such experiences through reflection essays, projects, or presentations, helping students process and understand the value of what they have learned. The SL approach would offer students real-world experience, allowing them to see how their academic knowledge translates into practical applications.

SL activities would also promote growth through community service or teamwork, enabling the development of positive affect states and emotions. This learning experience would also be tailored to align with students’ academic interests, with accountability ensured by linking these experiences to academic credit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.P. and M.V.; methodology, M.G.P., R.G., A.C.B. and M.V.; formal analysis, R.G. and M.V.; data curation, M.G.P.; original draft preparation, R.G., A.C.B., M.V. and M.G.P.; review and editing, M.V. and M.G.P.; supervision and project administration, M.G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was conducted at CIPsi, School of Psychology, University of Minho, supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT; UID/01662: Centro de Investigação em Psicologia) through national funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human and Social Sciences Ethics Committee of the University of Minho (CEICSH021/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

For privacy reasons, data is unavailable but will be made available upon reasonable request to the first author.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Maria Miguel Costa for her help with data collection and all the students who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASI-R | Affective State Inventory-Reduced |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| DERS | Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale |

| GFI | Goodness of fit index |

| GQ-6 | Gratitude Questionnaire |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| PSS-10 | Perceived Stress Scale |

| PWB | Psychological well-being |

| PWS | Psychological Well-Being Scale |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error approximation |

| SCS | Self-Compassion Scale |

| SRMR | Standardized root mean square residual |

| SwL | Satisfaction with Life Scale |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

References

- Ahrens, C. J. C., & Ryff, C. D. (2006). Multiple roles and well-being: Sociodemographic and psychological moderators. Sex Roles, 55, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akeman, E., Cannon, M. J., Kirlic, N., Cosgrove, K. T., DeVille, D. C., McDermott, T. J., White, E. J., Cohen, Z. P., Forthman, K. L., Paulus, M. P., & Aupperle, R. L. (2022). Active coping strategies and less pre-pandemic alcohol use relate to college student mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 926697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aristovnik, A., Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., & Umek, L. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lives of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability, 12, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta, C. N., Fritz, M. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2017). Functions of positive emotions: Gratitude as a motivator of self-improvement and positive change. Emotion Review, 9, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, S., Mudassar, A., Shahzad, T. Z., Raouf, M., & Pervaiz, T. (2020). Frequency of depression, anxiety, and stress among university students. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(5), 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatens, I., Vanderfaeillie, J., Soyez, V., Vantilborgh, T., Van Den Meersschaut, J., Schotte, C., & Theuns, P. (2022). Subjective well-being and psychological symptoms of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a structured telephone interview in a large sample of university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 889503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F., Blank, L., Cantrell, A., Baxter, S., Blackmore, C., Dixon, J., & Goyder, E. (2022). Factors influencing mental health of university and college students in the UK: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 22, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprara, G. V., & Steca, P. (2007). Prosocial agency: The contribution of values and self–efficacy beliefs to prosocial behavior across ages. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(2), 218–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilho, P., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, J. (2015). Evaluating the multifactor structure of the long and short versions of the self-compassion scale in a clinical sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(9), 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clair, R., Gordon, M., Kroon, M., & Reilly, C. (2021). The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic. Humanities & social Sciences Communications, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1996). Satisfaction and comparison income. Journal of Public Economics, 3, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, J., Ribeiro, E., Ferreirinha, R., & Dias, P. (2010). Versão portuguesa da escala de dificuldades de regulação emocional e sua relação com sintomas psicopatológicos [Portuguese version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale and its relationships with psychopathological symptoms]. Revista de Psiquiatria Clínica, 37(4), 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, E., Rich-Ruiz, M., Gutiérrez-Domingo, T., Luque, B., Castillo-Mayén, R., Villaécija, J., & Farhane-Medina, N. Z. (2022). Regulatory emotional self-efficacy and anxiety in times of pandemic: A gender perspective. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 11(1), 2158831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diedrich, A., Grant, M., Hofmann, S. G., Hiller, W., & Berking, M. (2014). Self-compassion as an emotion regulation strategy in major depressive disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy, 58, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahim, A. H., Dhahi, A., Husain, M. A., & Jahrami, H. (2022). The psychological well-being of university students amidst COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping review, systematic review and meta-analysis. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 22(2), 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erzen, E., & Ozabaci, N. (2023). Effects of personality traits, social support and self-efficacy on predicting university adjustment. Journal of Education, 203, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L. J., & Gunnell, K. E. (2016). Eudaimonic Well-being: A Gendered Perspective. In J. Vittersø (Ed.), Handbook of eudaimonic well-being. International handbooks of quality-of-life (pp. 427–436). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fernández, V., Losada-Baltar, A., Márquez-González, M., Paniagua-Granados, T., Vara-García, C., & Luque-Reca, O. (2020). Emotion regulation processes as mediators of the impact of past life events on older adults’ psychological distress. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(2), 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd. ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, M. W., Smith, L. J., Richardson, A. L., D’Souza, J. M., & Long, L. J. (2021). Examining the longitudinal effects and potential mechanisms of hope on COVID-19 stress, anxiety, and well-being. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 50(3), 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J. J., Uusberg, H., & Uusberg, A. (2019). Mental illness and well-being: An affect regulation perspective. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Harlianty, R. A., Wilantika, R., Mukhlis, H., & Madila, L. (2022). The role of gratitude as a moderator of the relationship between the feeling of sincerity (Narimo ing Pandum) and psychological well-being among the first year university students. Psychological Studies, 67, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Graafsma, T., Bohlmeijer, E., & Jong, J. (2021). Positive emotions as a potential mediator of a multi-component positive psychology intervention aimed at increasing mental well-being and resilience. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. (2013). Gender differences in academic self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, M., & Jovanović, V. (2020). The relationship between gender and life satisfaction: Analysis across demographic groups and global regions. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 23, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakasidou, E., Raftopoulou, G., Papadimitriou, A., & Stalikas, A. (2023). Self-compassion and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study of Greek college students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20, 4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardas, F., Zekeriya, C. A. M., Eskisu, M., & Gelibolu, S. (2019). Gratitude, hope, optimism and life satisfaction as predictors of psychological well-being. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 19(82), 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A., Kailash, S. Z., Sureshkumar, K., Sivabackiya, C., & Rumaisa, N. (2022). Gender differences in emotional regulation capacity among the general population. International Archives of Integrated Medicine, 9(1), 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kotera, Y., Green, P., & Sheffield, D. (2019). Mental health shame of UK construction workers: Relationship with masculinity, work motivation, and self-compassion. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 35(2), 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Y., Cao, H., Leung, D. Y., & Mak, Y. W. (2020). The psychological impacts of a COVID-19 outbreak on college students in China: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, K. Y. H., Stead, G. B., & Liao, C. Y. (2021). A meta-analysis of the relation between self-compassion and self-efficacy. Mindfulness, 12, 1878–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychological Review, 32(6), 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcoulides, K. M., & Raykov, T. (2019). Evaluation of variance inflation factors in regression models using latent variable modeling methods. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 79(5), 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, L., Valenzuela, L. S., & Soto, V. E. (2022). Well-Being amongst college students during COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from a developing country. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Măirean, C., Turliuc, M. N., & Arghire, D. (2019). The relationship between trait gratitude and psychological wellbeing in university students: The mediating role of affective state and the moderating role of state gratitude. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20, 1359–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, T., & Shaukat, M. (2014). Life satisfaction and psychological well-being among young adult female university students. International Journal of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, 2(5), 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, J. M., & Gamboa, P. (2016). Inventário de Estados Afetivos-Reduzido: Uma medida multidimensional breve de indicadores emocionais de ajustamento [The affective state inventory–reduced: A brief multidimensional measure of emotional indicators of adjustment]. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación—E Avaliação Psicológica, 1(41), 132–144. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, K. D. (2023). Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 74(1), 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, F. (2007). Forgiveness, personality and gratitude. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(8), 2313–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, B. (2018). Does higher education increase hedonic and eudaimonic happiness? Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, R. F., Duarte-Silva, E., & Peralta, E. (1997). O bem-estar psicológico em adultos: Estudo das características psicométricas da versão portuguesa das escalas de C. Riff. In M. Gonçalves, I. Ribeiro, S. Araújo, C. Machado, L. S. Almeida, & M. Simões (Eds.), Avaliação psicológica: Formas e contextos [Psychological evaluation: Forms and contexts] (Volume V, pp. 313–324). APPORT/SHO. [Google Scholar]

- Oguni, R., & Otake, K. (2020). Prosocial repertoire mediates the effects of gratitude on prosocial behavior. Letters on Evolutionary Behavioral Science, 11(2), 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, R., & Kumar, V. (2017). A study on life satisfaction and emotional well-being among university students. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(2), 112–116. Available online: http://www.iahrw.com/index.php/home/journal_detail/19#list (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Pais-Ribeiro, J., Silva, I., Ferreira, T., Martins, A., Meneses, R., & Baltar, M. (2007). Validation study of a Portuguese version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Psychology Health & Medicine, 12(2), 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J. E. P., Enríquez, M. D. C. Z., Cuadras, G. G., Ledezma, Y. R., & Vega, H. B. (2015). Perceived self-efficacy in teamwork and entrepreneurship in university students. A gender study. Science Journal of Education, 3(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portocarrero, F. F., Gonzalez, K., & Ekema-Agbaw, M. (2020). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between dispositional gratitude and well-being. Personality and Individual Difference, 164, 110101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Póka, T., Fodor, L. A., Barta, A., & Mérő, L. (2024). A Systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of self-compassion interventions for changing university students’ positive and negative affect. Current Psychology, 43, 6475–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmania, F., Tri Hutami, P., Rahmayanti, F., & Muslaini, R. (2020). Emotional regulation and psychological well-being in patients with diabetes mellitus. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 5(8), 1652–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renati, R., Bonfiglio, N. S., & Rollo, D. (2023). Italian university students’ resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown—A structural equation model about the relationship between resilience, emotion regulation and well-being. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(2), 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rufino, K. A., Babb, S. J., & Johnson, R. M. (2022). Moderating effects of emotion regulation difficulties and resilience on students’ mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 28(2), 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D. T., Chai, W., Li, X., & Dou, D. (2023). Profiles and predictors of mental health of university students in Hong Kong under the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1211229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simões, A. (1992). Ulterior validação de uma escala de satisfação com a vida (SWLS) [Further validation of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS)]. Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia, 3, 503–515. [Google Scholar]

- Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., de Pablo, G. S., Shin, J. L., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2022). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soper, D. S. (2019). A-priori sample size calculator for hierarchical multiple regression [Software]. Available online: http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Stallman, H. M. (2010). Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Australian Psychologist, 45(4), 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K. S. (2018). The Use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, M. A. Q., Khoury, B., Chau, N. N. T., Van Pham, M., Dang, A. T. N., Ngo, T. V., Truong, T. M., & Le Dao, A. K. (2024). The role of self-compassion on psychological well-being and life satisfaction of vietnamese undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Hope as a mediator. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 42, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, M., Canudo, N., Branco, F., & Silva, D. (2010). Estudo das propriedades psicométricas da Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) na população portuguesa [Psychometric proprieties of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) in the portuguese population]. Psychologica, 53, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X., Li, Y., & Zhang, W. (2019). The mediating role of negative emotions between emotional intelligence and psychological well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 78, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).