Envisioning Global Education in Rwanda: Contributions from Secondary School Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the level of knowledge and awareness of GE among secondary school teachers on Kicukiro district, Rwanda?

- What are the teachers’ perceptions toward the inclusion of GE in teaching and learning in their schools?

- What are the challenges teachers face when incorporating global education and perspectives into their teaching?

1.1. Global Education: An Educational Approach Still to Be “Global”

“Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and strengthening, and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. Furthermore, it shall promote understanding, tolerance, and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.”2

1.2. Global Education and the Rwandan Context

1.3. Teachers’ Role in Global Education Implementation

Limited research exists on the case of GE in Rwanda, particularly regarding teachers. A recent analysis by Niyibizi et al. (2023) on GE in initial teacher education and school curricula highlights the need for greater investment in this area. This is especially important given the tensions within the competence-based curriculum between addressing national needs (particularly the promotion of national identity) and incorporating broader global perspectives.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participant Profiles

3.2. Teacher Knowledge and Awareness of Global Education and Global Issues

3.3. Importance and Inclusion of GE in the Curriculum

3.4. Challenges to Teaching Global Issues

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBC | Competence-Based Curriculum |

| GCE | Global Citizenship Education |

| GE | Global Education |

| GENE | Global Education Network Europe |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| REB | Rwanda Education Board |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| UN | United Nations |

| 1 | Competence-Based Curriculum (CBC) is a curriculum Framework adopted by the Rwandan government in 2016 with the aim of developing learners’ competences rather than just their knowledge. It is characterized by approaches that are learner-centered, criterion-referenced, constructivist, and learning outcomes rather than content definition (REB, 2015). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | A European network of governmental bodies and other agencies in education and development, with influence on national policies. |

| 4 | Considered to be a non-formal citizenship and values education program for high school leavers in post-genocide Rwanda. |

| 5 | Solidarity camps for students, teachers, government officials and returnees. |

| 6 | A national service for those between 10–35 years old to develop a sense of fraternity and national identity among the Rwandan youth. |

| 7 | A concept that breaks tribal beliefs brought by the colonial government and seeks to promote Rwandan values and beliefs. |

| 8 | We are together and also signifies unity. |

| 9 | Kicukiro district has 10 administrative sectors: Gahanga, Gatenga, Gikondo, Kanombe, Kagarama, Niboyi, Kigarama, Kicukiro, Masaka and Nyarugunga. |

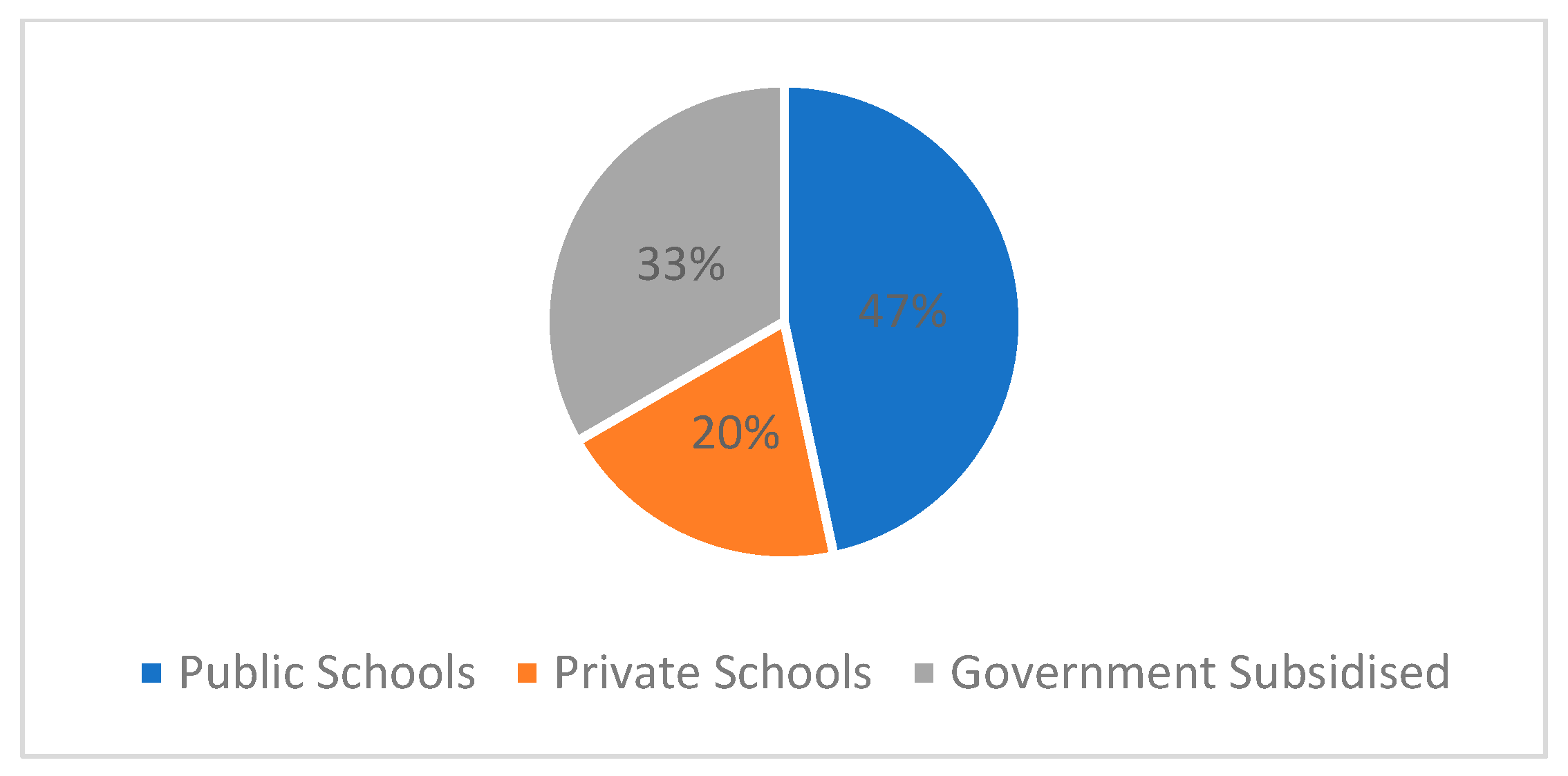

| 10 | School categories included public schools, government-subsidised schools, and private schools. |

References

- Academic Network on Global Education & Learning (ANGEL). (2022). Global education digest 2022. Development Education Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Albright, A. (2019). The global education challenge: Scaling up to tackle the learning crisis. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-global-education-challenge-scaling-up-to-tackle-the-learning-crisis/ (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Altun, M. (2017). What global education should focus on. International Journal of Social Sciences & Educational Studies, 4(1), 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, V., & de Souza, L. (2008). Translating theory into practice and walking minefields: Lessons from the project “through other eyes”. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 1(1), 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, V., & de Souza, L. (2012). Postcolonial perspectives on global citizenship education (Vol. 1). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ariely, G. (2012). Globalisation and the decline of national identity? An exploration across sixty-three countries. Nations and Nationalism, 18(3), 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, R., Zakaria, S., Isa, N., Majid, N., & Razman, M. R. (2021). Teachers’ perception and roles regarding global Citizenship for sustainable development. Ecology, Environment and Conservation, 27(1), 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bosire, A. M. (2022). Towards a curriculum for global education integration and implementation in Sub-Saharan Africa: An analysis of Rwanda’s secondary school curriculum. University of Porto. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/145157 (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Bourn, D. (2016). Teachers as agents of social change. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 7(3), 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D. (2018). The global teacher. In Understanding global skills for 21st century professionals (pp. 163–200). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D. (2020). The emergence of global education as a distinctive pedagogical field. In D. Bourn (Ed.), The Bloomsbury handbook of global education and learning (pp. 11–22). Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- British Council. (2022, May 30). British council-Rwanda. Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.rw/programmes/education (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Bruce, J., North, C., & Fitzpatrick, J. (2019). Globalisation, societies and education preservice teachers’ views of global citizenship and implications for global citizenship education. Globaliation, Societies and Education, 17(2), 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezudo, A., Cicala, F., Luisa De Bivar Black, M., & Carvalho Da Silva, M. (2019). Global education guidelines-concepts and methodologies on global education for educators and policy makers responsibility: North-south centre of the council of Europe. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/north-south-centre/global-education-resources (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Capalbo, R. (2013). Global education brief. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/31146085/Global_Education_Brief (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Catterall, P. (2011). Democracy, cosmopolitanism and national identity in a ‘globalising’ world. National Identities, 13(4), 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, D. P., Caramelo, J., & Açıkalın, M. (2020). Global education in Europe at crossroads: Contributions from critical perspectives. Journal of Social Science Education, 19(4), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, D. P., Caramelo, J., Amorim, J. P., & Menezes, I. (2022). Towards the transformative role of global citizenship education experiences in higher education: Crossing students’ and teachers’ views. Journal of Transformative Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, L. (2008). Interruptive democracy in education. In J. Zahjda, L. Davies, & S. Majhanovich (Eds.), Comparative and global pedagogies: Equity, access & democracy in education (pp. 15–31). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, J., & Robinson-Jones, C. (2022). Bridging theory and practice: Conceptualizations of global citizenship education in Dutch secondary education. Globalization, Societies and Education, 22(2), 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischman, G. E., & Estellés, M. (2020). Global citizenship education in teacher education: Is there any alternative beyond redemptive dreams and nightmarish germs? In D. Schugurensky, & C. Wolhuter (Eds.), Global citizenship education and teacher education: Theoretical and practical issues (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 102–124). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadsby, H., & Bullivant, A. (Eds.). (2011). Global learning and sustainable development. In Teaching contemporary themes in secondary education (p. 180). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generation Global. (2024, November 26). Empowering Rwandan youth with global citizenship skills. Available online: https://www.reb.gov.rw/news-detail/empowering-rwandan-youth-with-global-citizenship-skills (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Global Education Network Europe. (2022, July 15). European congress on global education in Europe to 2050. Global Education Network Europe. Available online: https://www.gene.eu/ge2050 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Global Youth Connect. (2020). Rwanda. Global Youth Connect. Available online: https://www.globalyouthconnect.org/rwanda (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Goren, H., & Yemini, M. (2015). Global citizenship education in context: Teacher perceptions at an international school and a local Israeli school. A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 46(5), 832–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanvey, R. G. (1982). An attainable global perspective. Theory into Practice, 21(3), 162–167. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1476762 (accessed on 20 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Inka, L., & Niina, S. (2013). Global education from a teacher’s perspective. Laurea University of Applied Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhoff, S. N., & Cloud, M. E. (2020). Equipping teachers with globally competent practices: A mixed methods study on integrating global competence and teacher education. International Journal of Educational Research, 103, 101629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurie, R., Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y., Mckeown, R., & Hopkins, C. (2016). Contributions of education for sustainable development (ESD) to quality education: A synthesis of research. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 10(2), 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwerier, T. (2020). Global citizenship education in west Africa: A promising concept? In Global citizenship education (pp. 99–109). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- la Velle, L. (2020). The challenges for teacher education in the 21st century: Urgency, complexity, and timeliness. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education-Rwanda. (2019). The republic of Rwanda ministry of education statistics. Available online: https://www.mineduc.gov.rw/index.php?eID=dumpFile&t=f&f=57556&token=46e2f488cbbedb7100d047093bf3e61cdaff908c (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Moloi, K. C., Gravett, S. J., & Petersen, N. F. (2009). Globalization and its impact on education with specific reference to education in South Africa. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 37(2), 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J. P., & Rivero, K. (2019). Preparing globally competent preservice teachers: The development of content knowledge, disciplinary skills, and instructional design. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Never Again Rwanda. (2022). Never again Rwanda. Available online: https://neveragainrwanda.org/en/who-we-are (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Niyibizi, E., Nyiramana, C., & Gahutu, C. (2023). Initial teacher training curriculum for global education in Rwanda: Between national and global perspectives and necessities. ZEP—Zeitschrift für Internationale Bildungsforschung und Entwicklungspädagogik, 46(3), 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzahabwanayo, S. (2018). What works in citizenship and values education: Attitudes of trainers towards the Itorero training program in post-genocide Rwanda. Rwandan Journal of Education, 4(2), 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Oxley, L., & Morris, P. (2013). Global citizenship: A typology for distinguishing its multiple conceptions. British Journal of Educational Studies, 61(3), 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmigiani, D., Jones, S. L., Silvaggio, C., Nicchia, E., Ambrosini, A., Pario, M., Pedevilla, A., & Sardi, I. (2022). Assessing global competence within teacher education programs. How to design and create a set of rubrics with a modified Delphi method. SAGE Open, 12(4), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, V. L. (2014). Stratified sampling. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics reference online (pp. 1–11). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Pashby, K., da Costa, M., Stein, S., & Andreotti, V. (2020). A meta-review of typologies of global citizenship education. Comparative Education, 56(2), 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdeková, A. (2015). Making UBUMWE power, state and camps in Rwanda’s unity-building project. Berghahn. Available online: www.berghahnbooks.com (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Quaynor, L. (2015). ‘I do not have the means to speak’: Educating youth for citizenship in post-conflict Liberia. Journal of Peace Education, 12(1), 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A. (2010). We cannot teach what we don’t know: Indiana teachers talk about global citizenship education. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 5(3), 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REB. (2015). Competence-based curriculum. REB/MINEDUC. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, F. (2020). What is global education and why does it matter? In F. Reimers (Ed.), Educating students to improve the world (pp. 25–29). Springer Open. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, R. (2015). Contesting and constructing international perspectives in global education. In R. Reynolds, D. Bradbery, J. Brown, K. Carroll, D. Donnelly, K. Ferguson-Patrick, & S. Macqueen (Eds.), Contesting and constructing international perspectives in global education (1st ed., pp. 27–43). Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Roiha, A., & Sommier, M. (2021). Exploring teachers’ perceptions and practices of intercultural education in an international school. Intercultural Education, 32(4), 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G. (2018). Global discourses and local practices: Teaching citizenship and human rights in post genocide Rwanda. Comparative Education Review, 62(3), 385–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saperstein, E. (2020). Global citizenship education starts with teacher training and professional development. Journal of Global Education and Research, 4(2), 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweisfurth, M. (2006). Education for global citizenship: Teacher agency and curricular structure in Ontario schools. Educational Review, 58(1), 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shar, N. H. (2024). Global citizenship education in government secondary schools: A case study of government secondary schools in northern Sindh [Doctoral thesis, UCL (University College London)]. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, J. (2013). Global education in Massachusetts: A study of the role of administrators [Doctoral thesis, Northeastern University]. [Google Scholar]

- Subedi, B. (2010). Reading the world through critical global perspectives. In B. Subedi (Ed.), Critical global perspectives: Rethinking knowledge about global societies (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 1–18). Information Age Publishing Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Taka, M. (2020). The role of education in peacebuilding: Learner narratives from Rwanda. Journal of Peace Education, 17(1), 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegay, S. M., & Bekoe, M. A. (2020). Global citizenship education and teacher education in Africa. In D. Schugurensky, & C. Wolhuter (Eds.), Global citizenship education in teacher education: Theoretical and practical issues (pp. 139–160). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2015). Global citizenship education: An emerging perspective. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2018). Reconciliation through global citizenship education. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2019). Educational content up close examining the learning dimensions of education for sustainable development and global citizenship education. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.gcedclearinghouse.org/sites/default/files/resources/200004eng.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- UNESCO. (2025). Global citizenship education and Peace Education. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/global-citizenship-peace-education/need-know?hub=87862 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Van Werven, I. M., Coelen, R. J., Jansen, E. P. W. A., & Hofman, W. H. A. (2023). Global teaching competencies in primary education. A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 53(1), 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghid, Y. (2021). Cultivating global citizenship education and its implications for education in South Africa. In E. Bosio (Ed.), Conversations on global citizenship education: Perspectives on research, teaching, and learning in higher education (pp. 62–71). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Willemse, T. M., ten Dam, G., Geijsel, F., van Wessum, L., & Volman, M. (2015). Fostering teachers’ professional development for citizenship education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 49, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolansky, W. D. (2016). Nurturing global education in its infancy. International Research and Review: Journal of Phi Beta Delta Honour Society for International Scholars, 6(1), 11. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Variable | Frequency (f) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 120 | 57.7 |

| Female | 88 | 42.3 | |

| Age | Below 25 | 12 | 5.8 |

| 26–30 | 56 | 26.9 | |

| 31–35 | 57 | 27.4 | |

| 36–40 | 44 | 21.2 | |

| 41–45 | 24 | 11.5 | |

| 46–50 | 10 | 4.8 | |

| 51–55 | 3 | 1.4 | |

| Above 56 | 2 | 1.0 | |

| Level of Education | Diploma | 21 | 10.1 |

| Bachelors | 172 | 82.7 | |

| Masters | 15 | 7.2 | |

| Teaching Experience | 1–2 Years | 31 | 14.9 |

| 3–5 Years | 53 | 25.5 | |

| 6–10 Years | 64 | 30.8 | |

| 11–15 Years | 42 | 20.2 | |

| 16–20 Years | 10 | 4.8 | |

| 21–25 Years | 4 | 1.9 | |

| 26–30 Years | 3 | 1.4 | |

| 31 years and more | 1 | 0.5 |

| No | Global Education Issues | Mode | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sustainable development | 3.000 | 3.034 | 0.677 |

| 2 | Sustainable lifestyles | 3.000 | 2.913 | 0.737 |

| 3 | Climate change and global warming | 3.000 | 3.111 | 0.683 |

| 4 | Environmental issues (e.g., desertification, destruction of tropical rainforests, and depletion of soil resources) | 3.000 | 3.067 | 0.670 |

| 5 | Global health (e.g., epidemics and diseases) | 3.000 | 3.024 | 0.684 |

| 6 | Migration (the movement of people) | 3.000 | 3.163 | 0.661 |

| 7 | The promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence | 3.000 | 3.144 | 0.651 |

| 8 | International conflicts and wars | 3.000 | 3.120 | 0.645 |

| 9 | Hunger or malnutrition in different parts of the world | 3.000 | 3.115 | 0.634 |

| 10 | Causes of poverty in the world | 3.000 | 3.159 | 0.644 |

| 11 | Equality between men and women in different parts of the world and in different sectors of life | 3.000 | 3.144 | 0.620 |

| 12 | Global citizenship | 3.000 | 2.572 | 0.795 |

| 13 | Human rights issues | 3.000 | 2.909 | 0.685 |

| 14 | Peoples’ different cultures and the appreciation of cultural diversity | 3.000 | 3.087 | 0.654 |

| % of Respondents on 4 and 5 * | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Importance 1. I believe global education is an important tool for helping students to become global citizens and in achieving the sustainable development agenda. | 95.7 | 4.35 | 0.578 |

| 2. Global education is important in Rwanda and globally, now and in the future. | 86 | 4.06 | 0.579 |

| GE in curriculum and schools 3. Global education should be incorporated into the school curriculum and be taught in schools. | 94.2 | 4.45 | 0.635 |

| 4. In Rwanda, education should focus less on global awareness and global issues, but more on the development of national identity. | 45.2 | 3.25 | 1.147 |

| 5. It is essential for secondary students to learn to become global citizens. | 91.4 | 4.27 | 0.691 |

| Item Description | % Respondents on 4 and 5 * | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual/Personal Constraints | |||

| 1. I have sufficient knowledge and skills to teach global education and global issues in school. | 31.3 | 3.00 | 1.019 |

| 2. My low-interest level hinders me from teaching global issues. | 17.7 | 2.70 | 0.953 |

| Systemic Constraints | |||

| 3. Education authorities and my school have provided me with continuous in-service training to improve my teaching skills on global issues. | 32.7 | 3.12 | 0.998 |

| 4. I am provided with sufficient and current materials such as books to teach global issues in school. | 26.4 | 2.95 | 0.984 |

| 5. The Competence-Based Curriculum policy allows me to teach global issues in school. | 22.1 | 2.84 | 0.957 |

| 6. The overall school climate hinders me from teaching global issues. | 20.7 | 2.82 | 0.914 |

| 7. I received training and materials on global education and global issues from the government through the Ministry of Education. | 23.5 | 2.94 | 0.915 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bosire, A.; Correia, L.G.; Coelho, D.P. Envisioning Global Education in Rwanda: Contributions from Secondary School Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050619

Bosire A, Correia LG, Coelho DP. Envisioning Global Education in Rwanda: Contributions from Secondary School Teachers. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):619. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050619

Chicago/Turabian StyleBosire, Abiud, Luís Grosso Correia, and Dalila Pinto Coelho. 2025. "Envisioning Global Education in Rwanda: Contributions from Secondary School Teachers" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050619

APA StyleBosire, A., Correia, L. G., & Coelho, D. P. (2025). Envisioning Global Education in Rwanda: Contributions from Secondary School Teachers. Education Sciences, 15(5), 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050619