1. Introduction

The prominence of multilingualism in today’s primary schools presents a significant challenge for initial teacher education (ITE) programs: ensuring that student teachers are prepared to support linguistically and culturally diverse learners in multilingual schools. This is particularly salient in Ireland, historically a country of emigration, which has become a hub of immigration and linguistic diversity in recent decades. Today, over 750,000 residents—representing more than 200 languages—speak a language other than English or Irish at home (

CSO, 2023). Among them, 78,412 school-aged children (5–12 years old) are multilingual learners and/or immigrants (

CSO, 2023). While national policy frameworks emphasize inclusive education (e.g.,

The Teaching Council of Ireland (

2020)’s Céim Standards for Initial Teacher Education), the extent to which student teachers are prepared to address the complex language and literacy needs in multilingual classrooms remain under-researched.

Over the past two decades, teacher professional development in Ireland has evolved through successive phases, showing a changing focus in the teaching of English as an additional language (EAL). Early initiatives (e.g.,

NCCA, 2006;

IILT, 2006) primarily targeted in-service teachers, equipping them with strategies for managing multilingual classrooms. More recently, efforts have shifted towards fostering a more inclusive, plurilingual approach that values students’ home languages and cultural backgrounds (

NCCA, 2015/2019,

2024). However, these developments have focused on teachers within multilingual schools. Therefore, it is timely to assess student teachers’ readiness for multilingual classrooms of their own and evaluate the contributions of current initial teacher education programs in addressing linguistic and cultural diversity.

To elaborate, early approaches to multilingual language education were rooted in a bilingual framework, centered on English and Irish (Gaeilge), with the assumption that learners would become balanced bilinguals (

Ní Dhiorbháin et al., 2024). However, contemporary perspectives have broadened to embrace a more inclusive orientation—one that acknowledges diverse home languages and fosters intercultural awareness within ITE programs. While the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) has long advocated for collaborative learning that engages with “the diversity of languages and cultures of children in the school” (

NCCA, 2006, p. 13), it is unclear how well-prepared student teachers are for this reality.

The Teaching Council of Ireland (

2020) reinforces the need for research-informed teacher preparation, emphasizing that student teachers should be engaged with “deconstructing what good teachers do in order for their teaching practice to be as inclusive as possible” (p. 8). This national policy framework has informed the accreditation and provided a structured pathway for embedding linguistically and culturally responsive pedagogy into Irish schools and ITE programs.

Despite these policy advancements, research on student teacher preparedness for multilingual Irish classrooms remains scarce. A small number of research papers by Irish stakeholders have highlighted the necessity for an ongoing focus on EAL in initial teacher education within diverse Irish contexts. The findings show a focus on creating inclusive curricula (

Bracken et al., 2010), the importance of grounding in EAL-related theory and basic and advanced practical coping strategies in Northern Ireland (

Skinner, 2010), and the development of culturally responsive practices and decolonizing pedagogy (

O’Toole & Skinner, 2018, drawing on the work of

Ladson-Billings (

2014) and

Martin et al. (

2017)). These studies have resulted in a consensus that if learners are to be supported in reaching their plurilingual potential, a key requirement is “professional training in language education for teachers so that they will have the expertise and confidence to integrate linguistic experience across the curriculum and contribute to a broader perception of language on the part of their pupils” (

Kirwan, 2014, p. 202). Furthermore, “what teachers have expressed is the need for pre-service and in-service education that will give them the expertise to respond to the demands of a changed demographic among the pupil population that will never return to the way it was” (

Kirwan, 2020, p. 52). Yet to date, Irish teacher education initiatives have largely taken an insider perspective, with internal institutional documentation of progress, module specifics, and gaps in student teacher preparedness for multilingual classrooms within Ireland.

At an international level, the Council of Europe’s European Centre for Modern Languages (ECML) has further advanced the conceptualization of plurilingual education, offering 11 practical recommendations for fostering the academic growth, plurilingual repertoires, and confidence of multilingual learners (

ECML, 2022). The ECML encourages pedagogies that leverage students’ home languages and promote language comparison, including the use of translation tools where appropriate, employing peer learning and varied assessment strategies. Two takeaways for the Irish context include first incorporating languages other than English and Irish (Gaeilge) into the classroom and second repurposing known literacy teaching strategies for EAL instruction towards plurilingual pedagogy.

Additionally, both the European Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education, henceforth European Guide, (

Beacco et al., 2016) and

The Teaching Council of Ireland (

2020)’s Céim Standards for Teacher Education, advocate for responsive, inclusive education. However, the European Guide takes a more reflexive approach to engaging with home languages and plurilingual education within curriculum development. This shift invites Irish ITE programs to review student teacher outcomes with European orientations to language education and teacher preparation by asking the critical question: what do student teachers need to know to effectively support young multilinguals learners in Irish primary schools? To date, the plurilingual dimensions of student teacher preparedness remains underexplored.

In responding to the need for empirical research on student teacher preparedness for multilingual classrooms in Ireland, we examine student teacher feedback from a fourth year Bachelor of Education (B. Ed.) elective module, Linguistic and Cultural Diversity in the Primary Classroom: English as an Additional Language, at Mary Immaculate College (MIC), Limerick, Ireland. Designed by the insider researcher in 2018 to move beyond a second language acquisition model towards a plurilingual and culturally responsive teaching approach (e.g., principles, stages, complexities, and pedagogical supports for teaching primary EAL) which incorporated European policy (

Beacco et al., 2016;

ECML, 2022), the MIC module has evolved iteratively using student teacher feedback, sustained engagement with local schools, a professional learning community, and European recommendations. We employ a longitudinal insider/outsider discursive case study, drawing on the methodological principles of reflexive thematic analysis (

Braun & Clarke, 2022). This collaborative design is particularly appropriate for the evolving context-sensitive nature of ITE. We examine student teacher reflections (

n = 35) across three iterations of the module in 2019, 2021, and 2023 on their learning and their readiness for teaching in multilingual classrooms.

The remainder of this paper critically examines existing literature on teacher preparation for multilingual classrooms in Ireland positioning our study within national and European policy context frameworks. Using the four levels of curriculum development proposed in the European Guide (

Beacco et al., 2016), we analyze their application to the elective MIC module, Linguistic and Cultural Diversity in the Primary Classroom: English as an Additional Language. We then present our research orientation and methodology, followed by a thematic analysis of student teacher reflections, presenting findings as “pockets of possibility” (

Erling et al., 2023, p. 72) which illustrate emerging insights around plurilingual pedagogy and suggest growth areas for agentive learning in teacher preparation. The paper concludes by considering the broader implications for research and the advancement of inclusive, reflexive teacher education in Ireland and internationally.

To begin, our analysis of the plurilingual approach is framed using the four levels of curriculum development presented in the European Guide (

Beacco et al., 2016). We describe the MIC module curriculum in focus in terms of the macro level of national policies, including

The Teaching Council of Ireland (

2020)’s Céim Standards. We also report on the meso level of institutional inputs shaping the module design and the micro level of objectives and instructional strategies within the module. In doing so, the nano level of student teachers’ autonomous reflections on their learning experiences is framed by the larger institutional and national structures.

Table 1 presents a schema of the module within this broader framework.

Using this structure, we review student teachers’ written responses for evidence of engagement with key concepts of multilingualism and plurilingual pedagogy, namely linguistic awareness and awareness of EAL strategies within plurilingual pedagogy. We then analyze the reflections for themes which present implications for local and international practices. Ultimately, our study aims to offer research-informed insights into the pockets of possibilities (

Erling et al., 2023), not only for the given module at MIC but also initial teacher education in other Irish and international contexts. This structure positions multilingual identities (

Forbes et al., 2021) and collective multicultural consciousness (

Forbes et al., 2021) as central to initial teacher education through the MIC module.

2. An Overview of Teacher Preparation for Multilingual Classrooms in Ireland

While migration is well understood within the history of Ireland, the economic boom in the mid-1990s and early 2000s and the expansion of the European Union (

Cushen, 2017) have changed patterns of immigration to Ireland. These economic and political factors underpin the growth of teacher development initiatives that address culturally and linguistically diverse students. Recognition of the home languages of the majority of children as English or Irish is evident at the macro level of national policies and curricular documents. However, statistics from 2023 show that 12% of the population were born outside of Ireland and about one in seven speak a language other than English and Irish (

Kavanagh & Neville, 2023). These sociocultural changes mean that primary schools today serve as dynamic sites where student teachers and teachers encounter a broadened array of languages. In this context, ensuring that student teachers are prepared to support multilingual classrooms is both an educational priority and a key challenge for ITE.

Over the past two decades, an evolving response to multilingualism in primary schools can be traced in Irish educational policy and curricular documents, research and teacher development initiatives. Our review spanning twenty years identifies three distinct phases as reactive, responsive, and reflexive, as shown in

Figure 1: Teacher development initiatives for multilingual classrooms.

The initial phase of teacher development in Ireland, spanning from the mid 1990’s to 2008, shows a reactive response to targeting increasing linguistic and cultural diversity within schools. While these efforts addressed important gaps in teacher knowledge within mainstream schools, their overall impact was limited and uneven. At the time, classrooms in mainstream schools were predominantly monolingual, with English as the primary language of instruction and Irish taught as a second language. However, Ireland’s economic boom in the mid-1990s to 2008 brought an influx of migrant students learning EAL, fundamentally altering the landscape of Irish schools. Initially, teachers encountered migration and multilingualism as an unexpected challenge, with little systematic guidance to support their evolving classroom needs. Statistics from this period recorded 170 languages spoken by new residents, a figure which has since expanded to over 200 languages nationwide (

CSO, 2023). During this phase, an early B.Ed. language and literacy module incorporated a limited number of lectures on the teaching of EAL appeared in ITE in Dublin, signaling tentative steps towards addressing multilingualism at the ITE level. Nevertheless, local guidance on teacher preparation to support linguistic and cultural diversity remained limited (

Kirwan, 2020), presenting significant challenges for teachers. In response, early reactive measures focusing on schools included the provision of EAL teaching posts, ad hoc professional development, and increased language support hours. However, the 2008 economic crisis led to a significant reduction in resources, increasing pressure on mainstream teachers to integrate EAL learners independently.

The second phase, which began to emerge from around 2011, marked a gradual shift towards more culturally and linguistically responsive approaches in both schools and ITE programs. This period also saw the introduction of the 2017 Special Educational Needs (SEN) allocation model, which endeavored to create a fluid continuum of support for both SEN and EAL learners, moving from whole-class integration to individualized instruction. However, limited references to EAL within the model and insufficient funding created significant challenges for teachers, particularly those in schools balancing high SEN populations alongside EAL needs (

Gardiner-Hyland & Burke, 2018). During this more responsive phase, schools faced dual pressures of structural reforms and constrained budgets, forcing EAL and SEN teachers to fulfil dual roles (

Gardiner-Hyland & Burke, 2018). This led to a problematic overlap where EAL students were sometimes treated through a SEN lens or vice versa, signaling a need for EAL teachers to advocate for discrete and integrated inclusive plurilingual education. Within ITE, this phase also saw more active institutional engagement, with MIC contributing to this trend through the introduction of a 36 h elective module in 2018-the focus of this study.

During this more responsive yet constrained phrase, teachers were often expected to manage the dual roles in supporting SEN and EAL learners. In addition, the new budgetary constraints required EAL teachers in Irish schools to respond strategically by developing relevant materials for collective use with multilinguals and advocating for the discrete needs of individual learners with school administrators. As such, this second phase underscored the need to develop advocacy roles in championing the needs of culturally and linguistically diverse students within resource-limited school environments. As suggested by

Gardiner-Hyland and Burke (

2018), student teachers may have experienced schools with inadequate resource allocations for multilingual children, while additional support was available in contexts of concentrated multilingualism only (

DES, 2017). These findings suggested an emergent need for teachers in schools to address issues of equitable provisions for all students. It also emphasized the value of reflexivity, adaptability, and proactivity in teacher preparation to ensure student teachers develop these qualities, now seen as essential for equipping future teachers to support diverse learners in resource-constrained and structurally complex educational environments. Moreover, this phase revealed that the primary challenge was not the presence of multilingual learners per say but the persistent time, resource and systemic constraints which limited teachers’ ability to effectively plan for and implement inclusive pedagogical teaching practices.

From 2019, a third phase of language education reform in Ireland marked a shift towards more inclusive and plurilingual teaching approaches within ITE programs. This phase reflects the gradual diffusion of concepts from supranational policies, such as those from the Council of Europe, into the national, or macro-level policies directing changes at the meso level. Specifically, ideas of plurilingualism, intercultural learning, and linguistic reflexivity began influencing both curriculum development in schools and ITE. To illustrate, the revised Primary Language Curriculum (

NCCA, 2024) and the Languages Connect Strategy for Foreign Languages in Education 2017–2026 (

Department of Education and Youth, 2017), launched by the Irish Department of Education, targeted foreign language education across the country. These curricula highlight the importance of language learning and provide guidance on how to integrate dual and multilingual approaches for the first time. They also emphasize skill transfer, language awareness, and modern foreign language teaching in upper primary classes.

Complementing this,

The Teaching Council of Ireland (

2020)’s Céim Standards advocated for responsive, inclusive education, which mapped key principles onto the draft Primary Curriculum Framework (

NCCA, 2023). These developments have broadened the scope beyond knowledge acquisition to assert that linguistic diversity is a facet of inclusive education. This phase featured concepts of linguistic reflexivity, plurilingualism, and intercultural learning into EAL instruction within student teacher modules.

One example is the Starlight Primary English Programme (

Folens, 2018) which involved the insider researcher embedding EAL strategies into thematic lessons for infant classes. Another initiative entitled the Migrant Teacher Project at

Marino Institute (

2017) addressed inclusion of internationally educated teachers. A further example is the development of guidelines for primary teachers, Language and Languages in the Primary School from Post-Primary Languages Ireland (

Little & Kirwan, 2021/2024), which emphasized the value of all languages within children’s linguistic repertoire. In addition, the recent establishment in 2024 of a national body for teachers’ professional development -Oide (named after an Irish word for teacher, tutor or professor), provided specialized EAL training, where capacity allows. Parallel developments included a revised allocation model for special education (

DES, 2024, p. 15) which introduced a three-tiered support structure of differentiation: Support for all (universal, preventive, and proactive); support for some (targeting groups and individuals), and support for few (intensified individual support). Two key

Department of Education Inspectorate Report (

2024a,

2024b), Meeting Additional Language Needs: Whole-school and Classroom Approaches for Inclusive Language Learning Findings from Primary and Post-primary school inspections of English as an Additional Language and The Quality of Education for Children and Young People from Ukraine, evaluated the quality of EAL instruction and the integration of learners, such as Ukrainian students, at a whole-school and classroom level. Collectively, these reforms reveal a growing alignment between Irish educational policy and the Council of Europe’s recommendations for plurilingual pedagogy.

During this period, a growing body of research on plurilingual pedagogy in Ireland drew attention to the meso level of school interventions for EAL. For instance,

Little and Kirwan (

2019,

2021/2024) reported on a whole-school plurilingual approach at Scoil Bhríde Cailíní, Dublin which used multiple languages of schooling (English, Irish, and French) and promoted home languages through integrated language learning and code-switching/mixing to enhance plurilingual pedagogy.

Gardiner-Hyland’s (

2021) study reported on EAL teachers’ experiences with navigating multilingual classrooms, highlighting their perceived levels of language development and diversity knowledge, challenges with collaboration and professional development, the need for inclusive practices and resources, and ways to accommodate and embracing diversity. Another study by

Ní Dhiorbháin et al. (

2024) investigated why multilingual parents (i.e., families where English or Irish is not the home language) enrolled their children in Irish immersion programs. The findings revealed that young multilingual children were able to use Irish to interact with culturally different neighbors, offering new reflexive insights into Irish immersion programs as a vehicle for linguistic and cultural inclusion. These findings ultimately affirm “the social cohesion of contemporary European societies” (

Beacco et al., 2016, p. 7). While Irish-medium education was not the first choice for all multilingual and immigrant families, it was often viewed as the best available option with positive appraisals of the cognitive and sociocultural benefits. These studies, along with

Little and Kirwan’s (

2021/2024) Language and Languages guidelines for schools and Council of Europe’s

ECML (

2022) 11 recommendations for plurilingual pedagogy, have served as formative influences in shaping orientations to good practice for student teachers and teachers in the face of multilingual classrooms.

2.1. Meso Orientations: Student Teachier Preparation for Multilingual Classrooms

Narrowing our focus to the meso level of student teacher preparation in Irish initial teacher education, the MIC module in focus was developed in parallel with other initial teacher education programs nationally. Among three established ITE programs, in Dublin (2) and Limerick (1), all had incorporated elements of linguistic reflexivity into instruction on second language teaching, EAL pedagogy, and leadership, as shown in

Figure 1. For instance, the Marino Institute of Education included a Language Study/EAL module within its B. Ed program and offered a number of postgraduate options on teaching EAL. Dublin City University’s School of Language, Literacy, and Early Childhood introduced an EAL specialism and embedded EAL content into core modules. MIC, Limerick, the site of the study, integrated five 36 h literacy electives into its B. Ed. program, amongst them electives on Linguistic and Cultural Diversity and Literacy Leadership in addition to ten lectures on EAL within the B.Ed. Year 2 program and six lectures on EAL in its Professional Masters of Education program.

Alongside these developments in ITE, there was a growing recognition of Professional Learning Communities for in-service teachers. This shift repositioned EAL teachers as active members of communities of practice, co-advocating for linguistic and cultural diversity in parallel with SEN-related concerns. One such professional learning community for EAL teachers in Limerick, “The TEAL Project”, was philanthropically funded though the Transforming Education Through Dialogue Projects (See

Léargas, 2021, video). Launched in 2019 by MIC’s Curriculum Development Unit in partnership with the Oscailt Schools Network, the project promoted culturally and linguistically responsive teaching over a six-year period from 2019–2025, reflecting

Stoll et al.’s (

2006) five characteristics of professional learning communities: shared values and vision, collective responsibility, reflective professional inquiry, collaboration, and promotion of individual and group learning, as seen in Irish initiatives. The TEAL Project aimed to upskill teachers in supporting migrant students as EAL learners and as agents of their home languages. Key outcomes included the development of plurilingual teaching strategies, resource materials, and leadership practices, positioning teachers as presenters, mentors, curriculum developers, writers, and change agents (

Gardiner-Hyland, 2025). These impacts extended to ITE, particularly into the MIC module under discussion. Tangible outputs, such as an online resource hub and the planned co-development of an EAL guidebook, exemplify the long-term benefits of sustained investments in professional learning communities. The TEAL Project demonstrates how inspiration drawn from the Council of Europe’s recommendations translated into actionable teacher preparedness efforts, inspiring the development of other communities of practice across Ireland and beyond.

With the

Council of Europe (

2022, p. 34) identifying teachers as “the agents of change”, Kirwan noted that the TEAL Project led by MIC in collaboration with Oscailt schools, Limerick illustrated the positive outcomes that inclusive, plurilingual classroom practices can generate (

MIC, 2025). She adds that owing to its achievements in Limerick in 2019, this initiative is set to expand across Munster in 2025–2026 as the Community of EAL Teachers (CEALT). This expansion bears the potential to benefit all participating pupils by helping them reach their full potential and in turn enable these pupils to contribute to the development of a socially cohesive and prosperous society from which all can benefit (

MIC, 2025). The projects’ outreach demonstrates a growing consensus that supporting linguistic and cultural diversity within Irish schools is a powerful mechanism for fostering social cohesion. The ongoing efforts to develop professional learning communities of EAL teachers across the region underscores the evolving landscape of teacher preparedness for multilingual classrooms. The initiative points to the development of a model for bringing student teachers into communities of practice alongside EAL teacher leaders, postgraduate researchers, and educators engaged in EAL practice and scholarship to collaborate and share expertise.

2.2. Supra-Level Connectionss: The Council of Europe’s Framework for Plurilingual and Intercultural Education

Research across international contexts underscores the importance of preparing student teachers to affirm linguistic and cultural diversity through pedagogical approaches that value students’ home languages and identities. Studies from Austria (

Lucas & Villegas, 2013), Belgium (

Sierens & Van Avermaet, 2014), and the US (

Sharroky, 2018;

Cummins, 2018;

García & Alonso, 2021) highlight how culturally and linguistically responsive preparation enables student teachers to scaffold learning, foster multilingual interaction, and support students’ academic and personal development in reaching their plurilingual potential (

Kirwan, 2014). These findings reinforce the need for ITE programs to move beyond generic language support for EAL learners and equip future teachers with targeted, research-informed strategies for affirming linguistic diversity in the classroom.

Turning to international policy influences, through the ECML, the Council of Europe has become an important source of guidance on plurilingual and intercultural education only recently. In 2022, the ECML outlined 11 recommendations for plurilingual school environments, which offered concrete strategies for addressing language barriers and leveraging students’ home languages through plurilingual teaching approaches. Also,

Beacco et al.’s (

2016) European Guide serves as a supra-level policy support available to European ITE programs and schools and provides a valuable framework for introducing plurilingual and intercultural learning within Irish ITE which merit closer attention.

Among the many contributions of the European Guide, one under-explored contribution is its organization of different inputs on curriculum development. Within ITE, the inputs extend beyond the individual actions of teacher educators to broader institutional and government influences. As illustrated in

Table 1, the inputs of curriculum planning and development derive from different bodies: international (supra), national/regional (macro), institutional (meso), classroom (micro), and coalesce at the nano-level of individual learning (

Beacco et al., 2016, p. 19). This layered perspective accounts for curriculum design that is not only shaped by the inputs of teacher educators and available resources, but also broader institutional structures, which influence the implementation in the classroom. In practice, student teacher assessments and module surveys constitute a valuable feedback loop at the nano and micro levels.

Another opportunity presented by the European Guide is its engagement with otherness and an openness to “intercultural discoveries” (p. 11). Related to this, the European Guide refers to linguistic reflexivity as an awareness of how languages function from different perspectives, and its attention on the European scale invites examination of how ITE programs contribute to the development of intercultural competence among student teachers, including developing skills in intercultural mediation. This perspective is a fresh direction for the MIC module, which aims to prepare student teachers for plurilingual pedagogies in future multilingual classrooms. It provokes a broader understanding of plurilingual competence that extends beyond English and Irish—the main languages of schooling—to include modern foreign languages, such as Spanish, French, or German, and the diverse home languages of Ireland’s increasingly multicultural population (

NCCA, 2024). This orientation to linguistic reflexivity tunes into the intercultural dimensions of language learning and European-informed vision of plurilingualism (

Beacco et al., 2016).

The reflexive orientation in the current phase positions student teacher’s own experiences with language and culture learning as a subject of analysis, reinforcing our interest in student teacher’s written course reflections. Student teacher surveys completed at the end of the MIC module provide insights into the linguistic and intercultural experiences that enhance their ability to support multilingual students. Their reflections constitute a nano-level response to teaching EAL, which can bring fresh understandings about the knowledge and skills needed for teaching in multilingual classrooms. Accordingly, we interpret their reflections on language learning and teaching as indicators of what student teachers need to know for teaching in multilingual classrooms. To date, insider perspectives of successful and innovative initiatives rest at the meso level of programming initiatives, but less is known about the preparations of future teachers from student teachers’ point of view. Using the MIC module as a stimulus, we wondered how learning about teaching in multilingual classrooms as a subject of analysis appears to student teachers; what their feedback can tell us about relevant linguistic and cultural encounters which prepare them for supporting multilingual students; and what their reflections can tell researchers and teacher educators about new directions for ITE programming.

In sum, in reviewing teacher preparation for multilingual classrooms in Ireland over the past two decades, we described three orientations to linguistic and cultural diversity: reactive, responsive, and reflexive. The reactive phase entailed taking stock of the immediate challenges of incoming students learning EAL in schools, with ad hoc in-service teacher workshops and early approaches in ITE, Dublin. The responsive phase highlighted further EAL modules in ITE, including the MIC module, a SEN allocation model of support for all, some, few with minimal reference to EAL in the context of resource constraints and yet new (often unofficial) roles for EAL teachers as advocates in schools. This phase also profits from curricular guidance at the national or macro level and programming at the institutional or meso level, particularly in ITE. Since 2019, student teachers in Irish ITE have access to revised national primary language curriculum guidelines (2019), Post-Primary Languages Ireland’s (PPLI) guidelines by

Little and Kirwan (

2019), and recommendations from the

Council of Europe (

2022). As important curricular influences from the macro and supra levels, these guidelines impart new understandings about teaching EAL which draw on principles of plurilingual and intercultural education. In addition, as mentioned earlier, professional learning communities have emerged as vehicles for ongoing teacher development. In orienting to student teacher reflections as a source of information on student teacher preparedness, we foreground the development of the MIC module as a significant meso-level initiative anchored by the potential to prepare student teachers to bring about inclusive, plurilingual teaching in multilingual classrooms.

3. Research Orientation

Given Ireland’s evolving plurilingual context, significant investments have been made in inclusive and linguistically and culturally responsive education (

The Teaching Council of Ireland, 2020;

NCCA, 2015/2019,

2024). Our study focuses on one micro-level intervention: a dedicated module at MIC, Limerick.

Framed as an evaluative case study with a collaborative, discursive approach, it draws on shared prior experiences in ITE in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) more than a decade earlier and our current insider/outsider positionings in relation to the Irish context. We acknowledge that student teacher preparedness is shaped by many inputs across the B. Ed program, including other modules and school placements, and that good research requires “in-depth understandings of specific settings and openness to complexity, contradiction, and re-interpretation” (

Hopkyns & van den Hoven, 2024, p. 66). Guided by a central concern with student teachers’ understandings of their preparedness for teaching in multilingual classrooms in Irish primary schools, our inquiry is framed by the research question: What do student teachers need to know for affirming cultural and linguistic diversity in multilingual classrooms in Irish primary schools? We begin by analyzing the multiple levels of inputs and interactions shaping teaching and learning within the MIC module,

Linguistic and Cultural Diversity in the Primary Classroom: English as an Additional Language, as shown in

Table 1: The Components of Planning the MIC Module. Moving beyond a linear critique of strengths and areas for development, we identify themes in student teacher reflections, which could be cast as pockets of possibility (

Erling et al., 2023) for advancing culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy in ITE.

3.1. Theoretical and Methodological Positioniongs

Our methodological and theoretical orientations shaped the steps taken in the research process. The development of the course was led by the insider researcher. The insider researcher followed participatory action research (

McNiff, 2017), theorized through the lens of communities of practice (

Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015), and professional learning communities (

Johannesson, 2022), having revised the module from its inception until 2024. The outsider researcher joined in 2024, bringing theoretical insights from social constructionism to highlight socialization processes involved in building professional knowledge and awareness of intercultural experiences (

Hopkyns & van den Hoven, 2024). These discussions about the MIC module as a micro-level influence repositioned student teachers’ feedback from course evaluations to discrete nano-level responses to macro-, meso- and supra–level influences. Our discursive process entailed drawing on our personal language learning and migration narratives. Our positionings as bilinguals shaped our interpretations of salient patterns in the student teacher survey data.

Our reflexive approach was informed by

Braun and Clarke’s (

2022) clarifications concerning flexibility to make choices about relevance, where theme development is constructed through the researchers’ research aims (i.e., gaining insights about student teachers’ preparation to affirm cultural and linguistic diversity within Irish schools today). Rather than bias, we used our life capital (

Consoli, 2022) to determine the relevance of the themes which offer recommendations for ITE and for research into student teacher preparation for multilingual classrooms. Our qualitative sensibilities are oriented to views of knowledge that come from our positions, whether an insider to the cultural context or outsider with a theoretical engagement in the topic, and, more notably, not developing claims based from numbers or cause and effect (

Braun & Clarke, 2022, pp. 6–7).

3.2. The Development of the Curriculum

The MIC module, Linguistic and Cultural Diversity in the Primary Classroom: English as an Additional Language, was a central means of teaching student teachers about plurilingual pedagogy in Irish primary schools. Developed as a 36-hour, Year 4 elective module in 2018, it aimed to promote student teacher readiness for linguistic and cultural diversity in Irish schools. Designed by the insider researcher and approved by the institutional academic course board, the module focused on the concept of variation in children’s oral language and literacy development for EAL learners. It also addressed cognitive and affective learning goals by engaging student teachers with the principles, stages, complexities, and inclusive practices necessary to support EAL learners. In addition, the module introduced language and intercultural learning as facets of EAL instruction relevant for multilingual students in Irish schools.

The curriculum evolved through a participatory action research approach (

McNiff, 2017) over six years from 2018 to 2024. The insider researcher, who designed, coordinated, and lectured on the 12-week module, employed an iterative process in collaboration with student teachers to revise select features of the module. One feature of this process was yearly student teacher surveys which served as an important feedback loop on the student teacher learning experience. Key responsive revisions included integrating technological resources from the ECML and research-informed guidelines for Irish primary schools (

Little & Kirwan, 2021/2024). Guest speakers, such as EAL Teacher Leaders from the TEAL Project in Limerick and experienced graduates, were invited to share expertise on local practices of plurilingual strategies and language support planning. The final assessment required collaboration with practicing teachers on the development of an academic e-poster and creation of original teaching resources. In addition, all student teachers were invited to submit contributions for consideration in an EAL guidebook publication for primary schools through the final assessment, which required collaboration with practicing teachers. In this way, student teacher agency and meaningful interactions with teachers in Irish schools were encouraged.

Another curricular element was the introduction of reflexivity embedded within several final year B. Ed. Modules under a ‘teacher as researcher’ framework. Student teachers were tasked with critically examining their language learning experiences, belief systems, and biases as second language learners to deepen understanding of diversity in the primary classroom. This reflexive approach provided a necessary foundation for appraising policy, curricula, and inclusive practices and synthesize international research about variation in oral language and literacy development among multilingual children. The module also introduced practical ways to include home languages of multilingual pupils in classroom activities. While this was framed as a vital step towards social cohesion and a plurilingual approach to language and literacy education, the insider researcher also encouraged student teachers to connect their learning with prior school placements where they encountered multilingual students. As shown in

Table 1, key components of the module were mapped onto the framework provided by the European Guide (

Beacco et al., 2016). This mapping illustrates how international frameworks and national and institutional polices (supra, macro, and meso levels) informed the module’s aims, content, and practices (micro level) with survey data offering insights from the nano level. The European Guide was included as a reference material, accessible online.

3.3. Methodological Approach

According to

The Teaching Council of Ireland (

2020)’s Céim Standards, the learning process “at this stage involves them deconstructing their identities so that their practice can be as inclusive as possible” (p. 7). As explained, isolating the module’s impact was not feasible, so we sought evidence of a “clearer and more concrete picture of what plurilingual and intercultural education can be when translated into practice” (

Beacco et al., 2016, p. 7), and considered strengths and gaps reported in student teacher surveys as important indicators of student teacher knowledge. In 2018, the insider researcher gained ethical clearance to study the student teacher surveys. To achieve a necessary critical distance, the insider researcher engaged an outsider researcher unfamiliar with the Irish context to analyze student teachers’ evaluations of the module in 2019, 2021, and 2023.

Survey data from 35 student teachers, as outlined in

Table 2: Phases of Data Collection and Analysis, were collected over three iterations: paper-based survey feedback in 2019 (

n = 16), online survey feedback in 2021 (

n = 7) and in 2023 (

n = 10), as well as emailed responses from 2023 in early 2024 (

n = 2). In 2019, the survey was distributed in paper form during class time. During the pandemic, the 2021 survey was distributed online, and in 2024, the module was taught by a second teacher, not the insider researcher. In 2024–2025, the outsider researcher manually coded the 35 responses and identified patterns to report in analytical discussions. The two researchers discussed the patterns using different methods under the shared aims of gathering insights into student teacher preparedness for multilingual classrooms.

The outsider researcher introduced research practices from linguistic duo-ethnography (

Hopkyns & van den Hoven, 2024) and reflexive thematic analysis (

Braun & Clarke, 2022) to the process. Student teachers’ self-reported knowledge was first analyzed with codes drawn from the European Guide. This phase of analysis featured deductive coding, drawing on statements of what student teachers need to know for fostering “social cohesion of contemporary European societies” (p. 7). The European resources framed the multilingual classroom as a micro-level linguistic ecosystem with broader social implications for the Irish context. As shown in

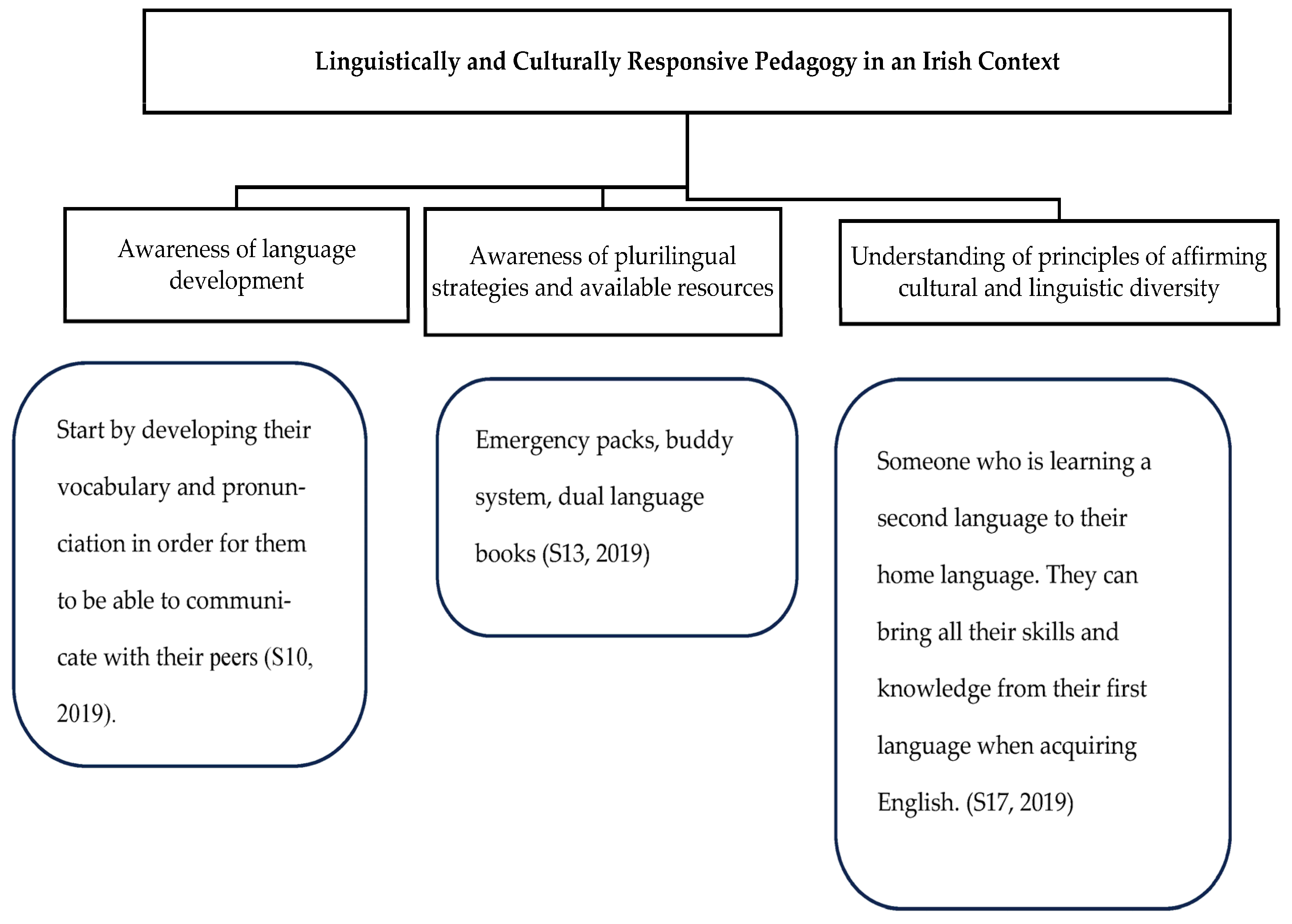

Figure 2: Example of preliminary coding, an initial stage of theme development entailed mapping student teachers’ written words onto principles espoused in the European Guide.

The preliminary phase of coding looked at statements about plurilingual education and sought patterns related to intercultural learning, backgrounding evaluations of the module. In other words, statements referring to empathetic statements of learning EAL or learning new cultural content from others were distinguished from those pertaining to awareness of inclusive, plurilingual teaching approaches and resources and “principles of affirming cultural and linguistic diversity” (

Beacco et al., 2016, p. 49). These patterns were then discussed as relating to references in

The Teaching Council of Ireland (

2020)’s Céim Standards to inclusive education, reflective practice, and Innovation, Integration, and Improvement, as underpinning all phases of ITE from induction to teacher’s ongoing professional learning. Other resources on the multilingual Irish classroom, such as

Little and Kirwan’s (

2021/2024) revised Language and Languages in the Primary School, were also consulted.

As practiced in linguistic duo ethnographies, our reflexive dialogue entailed talking about the data and using the process of talking to deepen the analyses based on our subject positions. In reflexive thematic analysis, the recursive dialogic process credits subjectivity as a resource for developing reflexive insights. In this methodology, reflexivity pertains to clarifying personal standpoints (values-based positionings), methodological dispositions, and disciplinary expertise. At times, the process entailed invoking our linguistic and professional profiles (as an English and Irish-speaking teacher educator with a hands-on approach to the module and a French- and English-speaking researcher and intercultural communication advisor). Our discursive approach served to delineate our priorities for theme development. In describing what student teachers need to know in light of challenges encountered in the MIC module, we also discussed how the module could be revised. Through sensitizing ourselves to the teacher development across three phases (i.e., reactive, responsive, and reflexive) in Ireland, we viewed the current phase as involving skills in “doing” plurilingual pedagogy within ITE programs, which entailed showing indicators of linguistic reflexivity as well as concrete ideas of implementing plurilingual and intercultural education in practice.

4. Themes

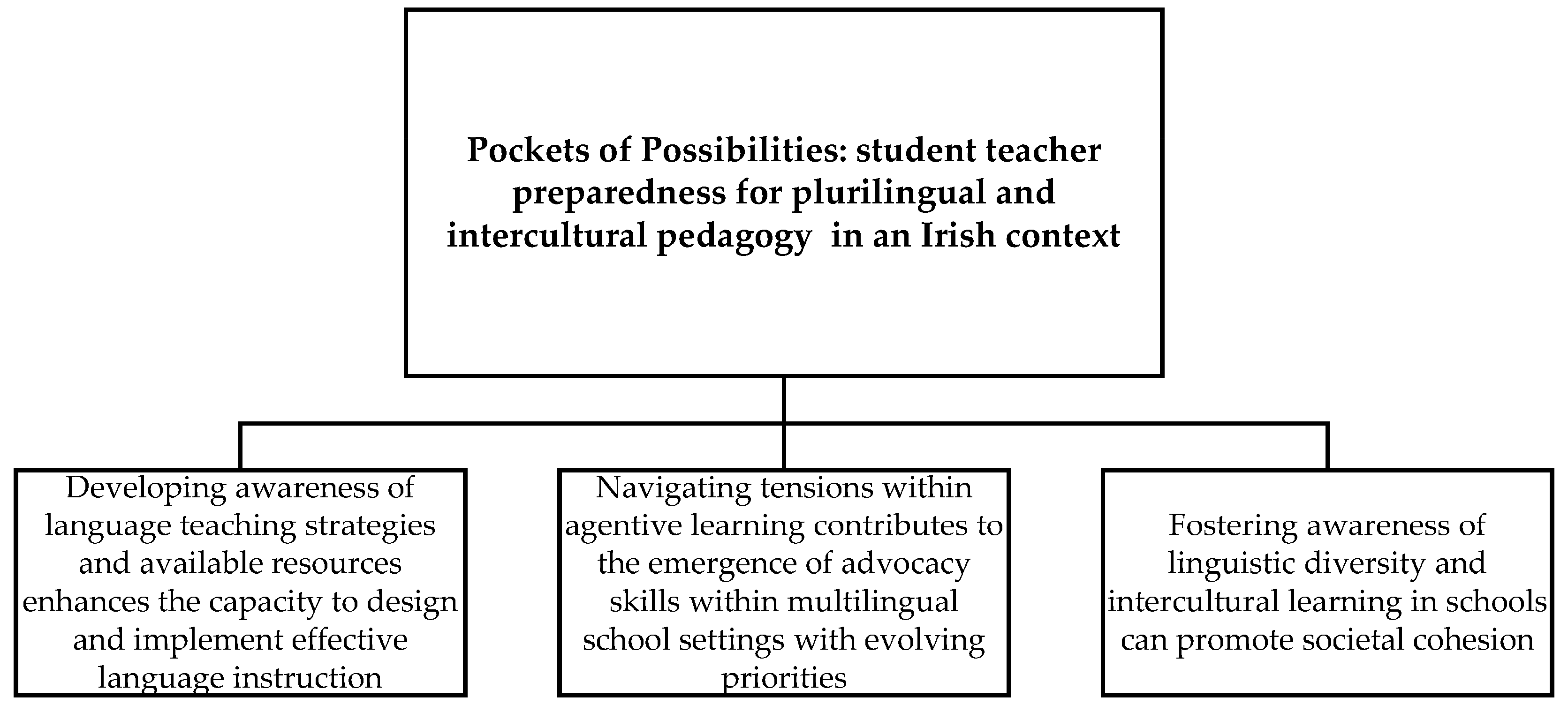

Through a process of reading and rereading the data in alignment with our analytical focus, we identified three interrelated themes focused on the preparation of student teachers for multilingual classrooms. A illustrated in

Figure 3: Possibilities for enhancing preparedness for multilingual classrooms, we identified three themes which answered our research questions about student teacher readiness for teaching in multilingual classrooms of their own: (1) developing awareness of language teaching strategies and available resources enhances the capacity to design and implement effective language instruction; (2) navigating tensions within agentive learning contributes to the emergence of advocacy skills within multilingual school settings with evolving priorities; and (3) fostering greater awareness of linguistic diversity and intercultural learning supports broader goals of societal cohesion. In reflecting on

Erling et al.’s (

2023) pockets of possibilities, we interpreted patterns in the data as indicative of a developmental trajectory towards becoming teachers equipped to navigate the complexities of plurilingual pedagogy in multilingual schools in Ireland.

4.1. Developing Awareness of Language Teaching Strategies and Available Resources Enhances the Capacity to Design and Implement Effective Language Instruction

Student survey responses indicated strong engagement with language teaching, relevant teaching activities, and resources appropriate for EAL learners in Ireland. Many reflections pointed to the use of online and concrete resources, suggesting that student teachers were introduced to a diverse set of pedagogical tools and strategies within the module. These included “emergency packs, buddy system, [and] dual language books” (S13, 2019) and learning “information about where to access materials and resources to support teaching EAL children” (S19, 2019), indicating both awareness and capacity building.

Student teachers recognized the value of differentiated instruction, with some highlighting the need for graded approaches. This was further reinforced by student teacher learning around “different approaches and strategies to teach EAL learners” (S5, 2019) and others noting the value of generalizable strategies and resources, such as “group work, practical ideas, resources (websites, games, interactive English programmes, etc.)” (S2, 2024). Such responses suggest that the module content successfully fostered a foundational awareness of how to plan and implement effective language instruction, including practical supports for EAL learners.

While the overall response was positive, showing an appreciation of the module’s relevance to future teaching, student teachers also expressed a need for deeper engagement with material development. One student teacher from the 2023 module suggested the inclusion of “a booklet of key resources as an EAL teacher” (S3, 2024) while another valued “creating practical resources that can be used in the classroom (assignment)” (S1, 2024). Notably, at the time of the module delivery, a dual hard-copy and amendable, online guidebook for EAL teachers was under development by the insider researcher. Student teacher awareness of this guidebook of plurilingual approaches tailored to an Irish context—its relevance, momentum, and the potential inclusion of their contributions—likely shaped their feedback.

The development of a guidebook exemplifies a key aspect of plurilingual pedagogy: the co-construction of practical tools informed by research, professional experience, and contextual knowledge. As

Consoli (

2022) notes, cultivating social and life embodies knowledge making and reflexivity, which stimulates “a process of growth facilitated by external forces” (p. 1398), where, for instance, learning about plurilingual pedagogy can lead to creative, agentive, and collaborative engagement. To illustrate, the insider researcher’s 30 years of teaching and lecturing experience, moving from an Irish-medium school (Gaelscoil) to international schools and higher education settings in both the Middle East and Ireland, informed the guidebook’s content and design. The new guidebook for multilingual education also drew on previous research and professional publishing experience as well as collaborative international research projects and direct supervision of student teachers in both Irish and international contexts. It also reflected stewardship of teacher leadership initiatives involving the TEAL Project professional learning community and cross-sectoral collaboration between teacher educators, EAL teacher leaders, and student teachers. Notably, assessment tasks strategically encouraged student teacher collaboration with practicing EAL teachers to address specific language issues, often highlighting unmet needs. Comments such as “mor [sic] emphasis on how EALs can access each aspect of the curriculum at each class level” (S17, 2019) and calls for more attention on “EAL teacher-planning requirements in school such as school support plans (SSPs) for EAL children (S1, 2024)” further demonstrate the potential growth area for agentive, collaborative, and inquiry-led preparation.

4.2. Navigating Tensions Within Agentive Learning Contributes to the Emergence of Advocacy Skills Within Multilingual School Settings with Evolving Priorities

Developing teacher agency is essential for navigating the complexity of multilingual classrooms. Our insider outsider collaboration examined student teacher feedback on the MIC module to identify strengths in preparedness, highlight gaps and challenges, and signal areas for improvement. Student teachers’ recommendations, while crisp, short, and often lacking the theoretical framing familiar to experienced teacher educators, offered a grounded perspective on readiness for practice. In contrast, in addition to the life capital highlighted previously, the experienced teacher educator/insider researcher drew on relevant theories, academic readings, and professional guides, revealing the nuanced, research-informed, skill-based competences required for effective plurilingual pedagogy in Irish classrooms. This contrast provided a useful lens through which to interpret student teachers’ criticisms or stressors as potential growth areas, commonly observed across the wider student teacher cohort.

Feedback reflected both logistical suggestions and assessment concerns. While some students commented on practical matters, such as “lecture times—late afternoon classes for a double were less desirable than early morning classes” (S16, 2019) and “I enjoy the asynchronous activities and the live lectures” (S3, 2021), others engaged with more substantive issues surrounding agentive learning. A recurring theme was the challenge of directing their own learning during the module’s summative e-poster assessment project, which required collaboration with a practicing EAL teacher.

Although praised by external examiners and part-time lecturers as an authentic and meaningful assignment with clear assessment criteria, guided steps and choices, the e-poster assessment surfaced tensions. Student teachers needed to display not only creativity but interpersonal, planning, and reflective skills, including empathy for the limited availability of practicing EAL teachers. Some comments included “trouble sourcing a teacher for the assignment” (S6, 2019) and “finding it tough to source a teacher who has the time to sign up to t-Rex and communicate on it as part of the assignment. All 3 teachers I contacted explained how busy they are at the minute” (S5, 2021). Others appreciated the relevance of the task, claiming it was “very worthwhile as it allowed us to review the content and apply it to everyday classroom situations” (S14, 2019).

Additional concerns centered on navigating the open-ended nature of the assessment. A few student teachers found it difficult to choose a topic or interpret assessment criteria. As noted by one student teacher, “The greatest challenge of the elective was to devise a topic for the assessment” (S12, 2019), and another asked for “further clarity around the assessment… particularly in relation to the creation of the resources component and what the 2000 words consists of” (S4, 2021). In response, sample assessments were shared on the module’s online resource repository, and an interactive session was introduced in later iterations, following a student teacher recommendation for “a Q and A session on the assessment in Week 7 to help us start thinking about the assessment” (S2, 2021).

These challenges should not be solely interpreted as gaps in knowledge but rather as developmental touchpoints in student teachers’ growing awareness of multilingual pedagogy. The assessment provided a space for student teachers to engage with real classroom issues, bridge theory with practice, build collaborative relationships, and learn from dialogic exchanges with teacher educators, peers, teachers, and guest speakers. According to the insider researcher, only a small subset of student teachers each year struggled with agentive learning despite access to detailed supports, such as sample e-posters, supplemental resources, and step-by-step guidelines. This suggests that while not universal, such tensions are informative indicators of where support structures and modeling of teacher agency can be enhanced so that student teachers become ready to take ownership and participate actively (

Erling et al., 2023).

The value of the assessment lay in its capacity to cultivate essential teaching competencies, ranging from clarifying complex tasks internal to the assessment and resolving external factors, such as managing logistical barriers and persuading busy teachers to collaborate. To elaborate, a range of work skills were needed to complete the assessment project planning, choosing a language or literacy issue for EAL learners in an chosen class/group and devising an academic e-poster inclusive of a mini-literature review and a resource bank, clarifying understanding of complex aspects of the task, resolving conflicts with logistics with practicing teachers who needed to offer discretionary time to help student teachers succeed with their assessment. These skills underpin preparation for multilingual classrooms, showing that student teachers’ preparation entails a sense of agency and a readiness for collaborating under time constraints. These skills are central to multilingual advocacy work. Indeed, fostering student teacher agency involves cultivating initiative, collaboration, and purposeful decision-making, enabling student teachers to respond meaningfully to diversity in schools. As identified in

The Teaching Council of Ireland (

2020)’s Céim Standards, agency pertains to awareness of student teacher roles to act intentionally, responsibly, and innovatively to strengthen relationships with peers, students, and teachers using professional conversations.

Student teacher responses also pointed to a desire for more structured discussions about EAL literacy issues, reflecting a readiness to assess professional roles and identities. Guest speakers were effective in presenting experiences within multilingual contexts, but could extend their contributions by modeling agentive teaching practices. One example is offering strategies for giving and receiving peer feedback, navigating school dynamics, and initiating collaborative inclusive dialogues on EAL in staffrooms. This orientation supports the view that developing advocacy skills requires not only exposure to classroom realities but also an insider’s understanding of how multilingual schools operate.

The theme of agency also connects with broader professional development pathways. Post-graduation, student teachers who view themselves as emerging EAL teacher leaders (

Gardiner-Hyland, 2021) are more likely to pursue further learning via Oide, the provider of Professional Development for teachers in Ireland, or Irish Education Support Centres, which offer sessions on EAL, assessment and leadership training within their continuous professional programming. With support for dual and plurilingual approaches in national

Department of Education Inspectorate Report (

2024a,

2024b) and the revised Primary Language Curriculum (

NCCA, 2015/2019,

2024), fostering agentive engagement with EAL teacher leadership is timely and necessary. The shared task of affirming new multicultural realities described as “large numbers of newcomer students” (

Gardiner-Hyland, 2025, p. 33) requires ongoing professional development and collaboration within a professional community.

Yet, as highlighted by the TEAL Project, and other initiatives for teachers in multilingual classrooms, advancing teacher preparedness for multilingual classrooms depends on systemic support and whole-school, distributed leadership (

Gardiner-Hyland, 2025). EAL teacher leadership still relies on the discretionary efforts of individual educators and available funding. For student teachers, preparation means not only mastering theoretically content (e.g., awareness of stages of language learning, proficiency benchmarks, plurilingual approaches and resources for teaching EAL) but also developing the advocacy and leadership skills to influence school practices, negotiate resources, and sustain collaborative professional communities.

In sum, while agentive learning may present initial tensions for some student teachers, it is a necessary and powerful driver of advocacy in multilingual school settings. By fostering student teacher agency, initial teacher education programs can prepare future EAL teacher leaders to navigate the complexities of multilingual classrooms. Agency is a vital and often overlooked driver of transformative practice and it is through navigating the tensions of agentive learning skills that student teachers are set on a path to developing advocacy for equitable and inclusive education.

4.3. Fostering Awareness of Linguistic Diversity and Intercultural Learning in Schools Can Promote Societal Cohesion

The MIC module was positively received not only for its practical relevance to multilingual classrooms but also for its broader cultural significance within an increasingly diverse Irish society. Student teachers acknowledged this connection in reflective feedback, describing the module as “interesting and relevant to today’s teaching climate” (S14, 2019) and “very relevant to today’s society—nation growing in diversity” (S15, 2019).

While these affirmations signal a willingness to support multilingual learners, most reflections lacked direct reference to specific cultural or linguistics identities encountered during school placements. Instead, general terms such as “EAL Learners” (S15, 2019) were frequently used, suggesting a conceptual rather than personalized engagement with linguistic diversity. Notably, in surveys there were no mentions of languages currently spoken by newer populations in Ireland, such as Ukrainian, Arabic, or Kurdish, despite the inclusion of guest lecturers and an e-poster assessment, which directly prompted such connections. Also, delivered in the final semester, after student teachers had completed their last school placement, the timing of the MIC module meant that student teachers would not be able to practice preparing for teaching multilingual learners before employment as teachers, which as identified by

Paulsrud and Gheitasi (

2024) in the Swedish context is needed for targeted planning to foster teacher preparedness for multilingual classrooms. This observation has informed future priorities by the insider researcher, including creating potentially stronger integration with other existing initiatives, including the Embracing Diversity Nurturing Integration Project (

Higgins et al., 2021) and re-introducing the use of platforms such as The Teaching Council of Ireland’s T-Rex.

Encouragingly, some feedback revealed an emerging intercultural awareness framed through ethno-relative perspectives (

Bennett, 2025), with student teachers recognizing diversity and cultural difference positively. Expressions of curiosity were evident, although sometimes perceived as peripheral to immediate professional goals. For instance, further exposure to intercultural experiences teaching outside Ireland could be an asset, as seen with one student teacher’s remark: “slightly unrelated but I would also love to hear more about teaching in the Middle East and what that was like—could be useful for anyone else considering it” (S4, 2021). While reflective of personal interest and ambition, this comment also highlights a missed opportunity to link global teaching experiences within local multicultural realities. As explained in

Dillon et al. (

2025), trained Irish educators are in high demand in overseas Middle Eastern contexts, such as reported in the UAE where 10% of expatriate teachers are Irish. Reflecting on this feedback in light of the global mobility of teaching staff, the insider researcher expressed plans to expand future school placement opportunities abroad, including visits to international schools in Europe or participation in short-term international exchanges, such as the current Erasmus partnership with a university in Austria.

However, a more dialogic approach to intercultural learning could encourage deeper engagement with student teachers’ own multilingual experiences. Culture-learning models such as the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (

Bennett, 2025) and the concept of collective multicultural consciousness (

Forbes et al., 2021) offer relevant frameworks for intercultural learning. For example, assignments could prompt student teachers to explore their own multilingual journeys via reflective writing tasks on “exposure to and interaction with languages across the lifespan” (

Forbes et al., 2021, p. 435) and foster deeper personal connections to the significance of inclusive plurilingual education. As noted by

Beacco et al. (

2016), effective plurilingual pedagogy “would be incomplete without its pluricultural and intercultural dimensions” (p. 20). When student teachers better understand how their own language(s) and culture(s) intersects with others, they are better equipped to foster classroom communities grounded in mutual respect, empathy, and social cohesion. Engagement with linguistic and cultural reflexivity sets student teachers on a path of personal enrichment which is an asset for teaching in multilingual classrooms of their own.

In summary, fostering awareness of linguistic diversity and intercultural learning is not simply about appreciating cultural diversity. Fostering linguistic and cultural awareness is about embedding inclusive plurilingual practices that sustain societal cohesion. Our reflexive thematic analysis offers several recommendations as pockets of possibilities for rethinking student teacher preparation for multilingual classrooms in Ireland, firstly, through expanding awareness of integrated language learning through teaching of plurilingual strategies through the development of a nationally distributed guidebook. Secondly, through strengthening student teacher agency through more structured dialogic interactions not only with teacher educators but also with multilingual guest speakers and EAL teacher leaders. Dialogic conversations could develop from the assessment focus on specific language and literacy issues in classrooms to the specific needs of multilingual identities within schools, and to professional challenges experienced by EAL teachers who advocate for EAL learners. Finally, promoting intercultural learning by embedding models of intercultural sensitivity and reflective writing tasks that encourage personal and professional connections to the multilingual realities of Irish society benefit intercultural awareness by “tuning into the perceptual experience of otherness” (

Bennett, 2025, p. 5). These interventions not only prepare student teachers for multilingual classrooms, but also inform their roles in shaping a more inclusive and societally cohesive future.

5. Discussion: Wider Significance for Student Teacher Preparation

The question of student teacher preparedness for teaching in multilingual classrooms is not simple. fixed answer but merit an evolving response alongside societal and policy changes. As Ireland continues to embrace its multilingual future, the preparation of student teachers is understandably an ongoing process. ITE reform demands adaptability, reflexivity, promotion of plurilingual teaching and learning in schools, intercultural competence, and collaborative leadership. This evolution offers a rich terrain for innovation and meaningful change within ITE. In this section, we reflect on the wider significance of our empirical insights by situating the MIC module within national and international discourses on plurilingual and intercultural education. Drawing on our conceptual framework and methodological stance, we reimagine ITE as a site for shaping not only pedagogically competent practitioners but also agentive professionals who are capable of navigating more inclusive and socially cohesive educational systems. In doing so, we highlight how our case study helps pockets of possibility to surface not only within the Irish context but the wider scope of transforming language education within increasingly diverse societies internationally.

Our orientation to contributing to

Erling et al. (

2023)’s mindset of pockets of possibilities stemmed from a commitment to reframe prevailing deficit narratives, which portrayed the teaching of EAL students in Irish primary schools as inherently problematic (

Gardiner-Hyland & Burke, 2018). In seeking empirical insights into student teacher preparation, we highlighted proactive, agentive, and context-sensitive strategies. Central to our approach was a discursive and dialogic collaboration between ourselves as insider and outsider researchers, leveraging complementary disciplinary and methodological expertise. This dual perspective provided a valuable lens for examining student teacher preparation for multilingual classrooms in Ireland, which, as captured in

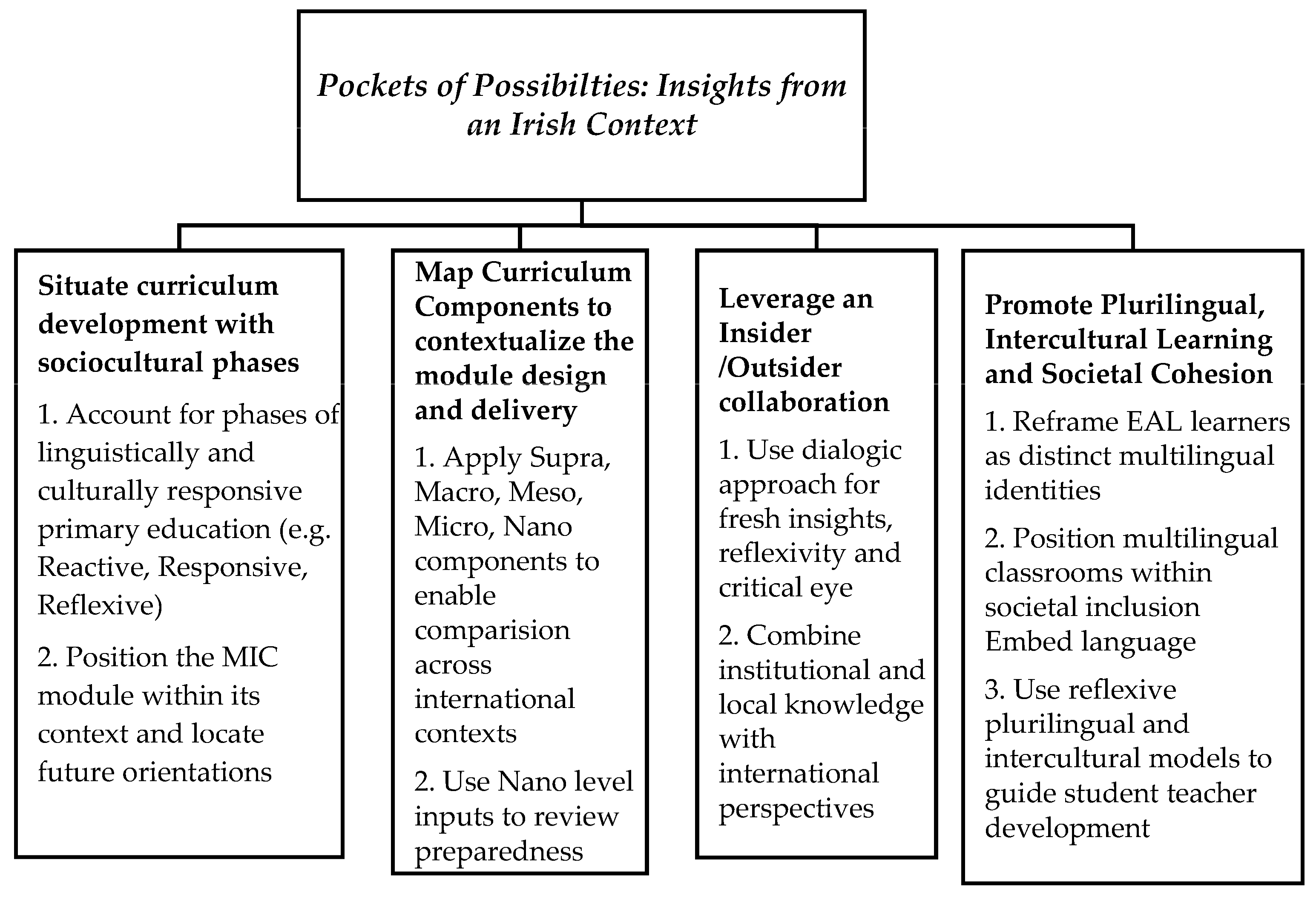

Figure 4: Pockets of Possibilities: Insights from an Irish Context considers relevance for stakeholders recognizing parallels in educational contexts globally.

Our examination of the broader positioning of the MIC module was built on defining the historical context, which helped us to understand the social and economic factors shaping new developments in both primary schools and ITE. Our overview led to classifying three orientations to linguistic and cultural diversity: reactive, responsive, and reflexive. While the reactive phase took stock of the pressing challenges of multicultural EAL learners in schools with limited systematic guidance to support evolving classrooms and early approaches to EAL within ITE, the ensuing responsive phase enabled new (and often unofficial) roles of EAL teachers as advocates in Irish schools, despite resource constraints and an increase in ITE provision for not only EAL but plurilingual education. This responsive phase of curriculum development saw the introduction of the MIC module while also recognizing that student teacher development is shared across multiple modules. We note that growth lies in the direction of a reflexive orientation premised on increased sensitivity to local realities of linguistic and cultural diversity. The first insight then was to establish how the MIC module fit into the responsive phase of curriculum development within the specific sociocultural context.

As a next step, we mapped the MIC module against the four layers of curricular input outlined in the European Guide (

Beacco et al., 2016). This framework allowed us to conceptualize the MIC module as a dynamic point of convergence between supra-level guidance documents, macro-level inputs of national policy, and meso-level parameters of institutional programming. At the nano level, student teachers’ reflections formed an essential feedback loop, illustrating how personal learning experiences can inform both module refinement and institutional planning and subtle variations at the micro level of curricular delivery.

This layered perspective reinforces the applicability of the European Guide (

Beacco et al., 2016) as both an evaluative and developmental framework for the Irish and international contexts. In applying it to our case study, we show how the responsive phase of Irish ITE profited from curricular guidance at both the level of international and national policies (supra and macro levels) and programming within the institutions (at the

meso level). We also used the layered perspective to not only identify concrete areas for module enhancement but also demonstrate the utility of the template for other initial teacher education contexts seeking to integrate plurilingual and intercultural approaches. As a second insight, then, the Guide enables comparison with similar modules in other contexts internationally.

Third, our insider/outsider methodological stance enabled a reflexive account of teacher education in Ireland to locate three phases of teacher development initiatives (i.e., reactive, responsive, and reflexive). We traced a three-phase trajectory through which an evolving agenda of linguistically and culturally responsive pedagogy emerged. Our case study contributes to this reflexive phase by asking what student teachers need to know and do to teach effectively in multilingual classrooms. In doing so, we also brought in supra policy discourses and transnational frameworks to foreground the interconnectedness of policy influence on teaching practices.

Fourth, the European Guide (

Beacco et al., 2016) underscores intercultural learning as a cornerstone for plurilingual education. By reframing EAL learners as multilingual learners with distinct multilingual identities (

Forbes et al., 2021), we shifted the narrative from remediation to recognition, and from deficit to potential. Within this framing, social cohesion emerges as a central goal, not only for Irish classrooms, but for democratic European societies at large. We proposed that Irish ITE is currently transitioning into a reflexive phase, in which integrating plurilingualism with interculturality involves actively promoting “the ability to participate in different cultures” (p. 10) through language learning. This means enhancing language awareness is central to this effort as it encourages student teachers to recognize language as both a cognitive tool and a driver of intercultural empathy. As explained in the European Guide, intercultural learning entails engagement with cultural diversity in our societies, and language learning is a vital means to develop reflexive orientations. These positionings mean student teacher preparation for multilingual classrooms involves learning from and about others for the broader aim of social cohesion.

Our data show that student teacher preparation must move beyond gaining pedagogical competencies to include the development of reflexive orientations imbued with notions of a collective multicultural consciousness (

Halse, 2022). As

Ní Dhiorbháin et al. (

2024) suggest, multilingual classrooms contribute not only to student learning but also to broader goals of societal inclusion and civic participation. Valuing multilingual speakers as potential intercultural mediators, whether they speak English, Irish, and/or other heritage languages, creates new possibilities for civic engagement and mutual respect.

The MIC module’s broader relevance also lies in its potential to influence other teacher education specializations. Its connections to electives like Children’s Literature, Literacy Leadership, and institutional partnerships such as with the TEAL and Embracing Diversity, Nurturing Integration projects highlights how language awareness, foreign language learning, plurilingual and intercultural sensitivity are mutually reinforcing. These crossovers can foster a holistic approach to multilingual education that spans disciplines, institutions, and communities.

Looking beyond Ireland, international frameworks also offer valuable insights. In an Austrian context,

Lucas and Villegas (

2013) draw on Feiman-Nemser’s (2001) framework to outline core tasks for preparing teachers of multilingual learners: building awareness of linguistic diversity, advocating for EAL students, analyzing socio-political and academic language demands. Importantly, they emphasize the need to recognize student teachers realistically as novices who are still in the process of developing their expertise as linguistically and culturally responsive teaching.

Erling et al. (

2023) further argue that educational environments favorable to translanguaging approaches can transform classroom dynamics, enabling students to feel valued in their multilingual identities. Their findings stress the importance of intercultural environments where teachers show a genuine interest in students’ linguistic and cultural worlds on student engagement and learning outcomes. Similarly,

Paulsrud and Gheitasi’s (

2024), writing in a Swedish context, stress the need for structured intercultural opportunities within ITE to ensure that differentiated lesson planning includes meaningful language inclusion.

6. Conclusions

With over 200 languages spoken in Ireland today among a population of 5 million, childhood multilingualism highlights the currency of preparing teachers for plurilingual education. These new patterns of cultural and linguistic diversity also prompt ITE to develop modules for preparing student teachers on teaching EAL in multilingual classrooms. The findings from our dialogic case study using reflexive thematic analysis illustrate the broader significance of student teacher preparedness for multilingual classrooms within an evolving Irish context of demographic changes. Drawing on three core themes of the study, we show that developing awareness of language teaching approaches and resources, fostering agentive learning for advocacy roles in multilingual schools, and deepening intercultural sensitivity all play essential roles in preparing student teachers for inclusive plurilingual education.

Each theme identifies areas of promise, referred to as pockets of possibilities (

Erling et al., 2023) which extend research and practice. These pockets are not isolated successes of the MIC module alone but should be seen as interconnected opportunities for building future plurilingual teaching capacity. They highlight how student teachers, when supported by responsive frameworks and authentic assessment, can begin to see themselves as advocates—through professional placements, whole-school EAL leadership, collaboration in professional learning communities such as the TEAL Project or CEALT, contributions to pedagogical resources and guidebooks, or by advancing broader goals of social cohesion.

Our methodological approach combines insider knowledge of module design with an outsider lens of intercultural education. Our dialogic and discursive approach enabled us to situate the MIC module within

Beacco et al.’s (

2016) framework in their Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education. In mapping the module across supra, macro, meso, micro, and nano levels of curricular inputs, we illustrated how the module responded to broader developments within Irish teacher education reform. In doing so, we underscored the transformative insights of our dialogic engagement on understanding the current state of student teacher preparedness, which resulted in a newfound appreciation for the vital role of reflection on multilingual and intercultural encounters for student teachers, and ultimately, the professional identities of teachers.

We also highlighted the value of linking these efforts to broader goals of social cohesion. Recognizing multilingual learners not through a deficit lens but as plurilingual individuals with distinct cultural and linguistic identities allows student teachers to imagine a future for Irish schools where equity, empathy, and civic participation are at the core. The pathways for professional learning communities within the TEAL and CEALT projects, signal the available pockets of collaboration when teachers in schools, teacher educators in college and policy advisors converge around shared values of plurilingual pedagogy and inclusive education.

Over the past two decades, this transition has culminated into a growing recognition of the need to integrate young EAL learners into Irish schools through a plurilingual rather than a deficit-based perspective. This paper accounted for key initial teacher education programs in Ireland that have integrated EAL, including those early adopters at Marino Institute of Education, Trinity College Dublin and Dublin City University.