Challenges and Opportunities of Multi-Grade Teaching: A Systematic Review of Recent International Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Questions

- What are the principal organizational characteristics of multigrade classrooms, as evidenced by the studies that have been analyzed?

- The following question is posed for consideration: what pedagogical methodologies are applied in these contexts, and what are the results of their application?

- The present study seeks to explore the way teacher training is approached in relation to working in multigrade classrooms.

- The following question is posed for discussion: what challenges and opportunities have been identified in the implementation of this educational model?

- The following question is posed for discussion: what recommendations, if any, can be drawn from the extant literature regarding the enhancement of the quality of education in multigrade classrooms?

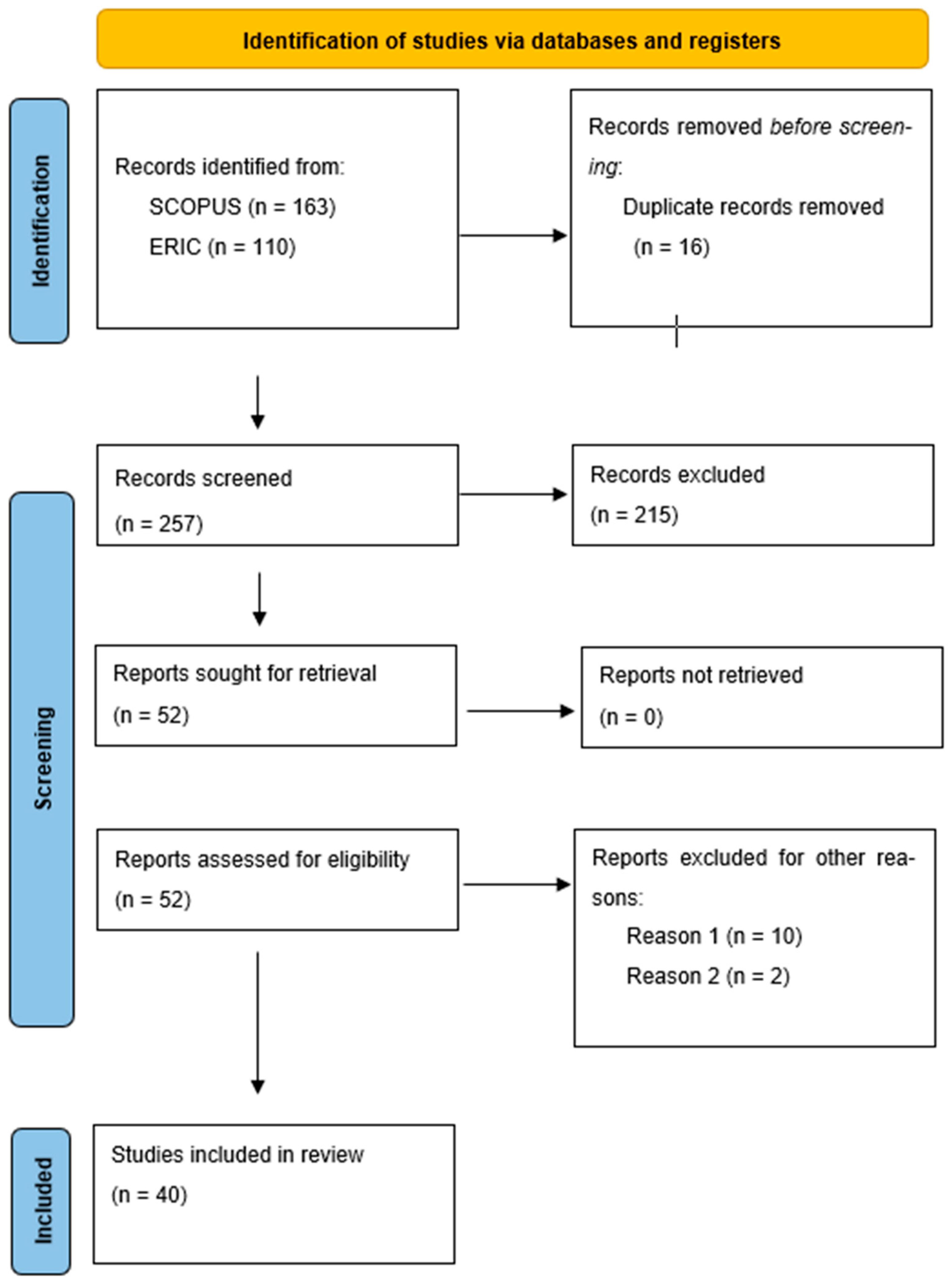

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Inclusion criteria

- Articles and book chapters

- Age limit of the last 5 years (2019–2024)

- Articles in any language

- Open-access scientific publications

- Studies focused on multigrade classrooms in rural and urban contexts, whose sample is framed in early childhood education, with emphasis on their organizational, methodological, formative, or pedagogical characteristics

- Exclusion criteria

- Articles without full access to the text

- Duplicated publications or with little methodological rigor

- Articles whose samples were not in Infant/Primary Education

- Articles prior to 2019

2.4. Article Selection Process

2.5. Analysis of the Information

- Comprehensive Reading: A thorough reading of the selected articles was carried out independently by each researcher but following the same criteria. Discrepancies were resolved at a review meeting of the categories that emerged.

- Grouping into Thematic Categories: organization of the initial codes into broader and more coherent thematic categories based on the recurrence of themes and identified interconnections.

- Open Coding: identification and coding of relevant text fragments.

- Interpretation and Synthesis: done for each of the categories that emerged and the meaning of what appeared in the text.

- Organizational models and school management: structures, groupings, and dynamics specific to multigrade classrooms.

- Teaching practices and active methods: teaching strategies used, with an emphasis on cooperative and personalized learning.

- Teacher training and professional development: initial and in-service training for teachers in multigrade contexts.

- Impact on learning and educational inclusion: observed impact on academic achievement, equity, and diversity.

- School-community relations and the territorial dimension: links between the socio-cultural environment and the functioning of education.

3. Results

3.1. Organizational Models and School Management

- The educational environment is characterized by the presence of single classrooms, wherein a single teacher is responsible for instructing students of varying levels. Such practices are particularly prevalent in small schools, especially in rural areas (Varga & Sabljak, 2020).

- The concept of combined classrooms is evident in schools that feature multigrade sections, which are integrated into larger educational centers. This phenomenon is exemplified by the case of incomplete Infant and Primary Education Centers (CEIP) in Spain, where the operation of certain levels is consolidated due to the progressive decline in enrolment (Boix & Buscà, 2020).

3.2. Pedagogical Practices and Active Methodologies

3.3. Teacher Training and Professional Development

3.4. Educational Strengths of the Multigrade Model

3.5. Challenges for Students, Teachers and the System

3.6. School-Community Relationship and Territorial Dimension

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations of the Study

5.2. Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abós, P. (2014). El modelo de escuela rural multigrado¿ es un modelo del que podamos aprender?¿ es transferible a otro tipo de escuela? [Can we learn the rural multigrade school? Has it a transferable model?]. Innovación Educativa, (24), 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktan, S. (2021). Waking up to the dawn of a new era: Reconceptualization of curriculum post COVID-19. Prospects, 51(1), 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga-Rojas, J., & Del Pino, M. (2024). Education evaluation policy in Chile: Experience at a multigrade rural school as a contribution to social justice. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 37, 95–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzures-Tapia, A. A. (2020). Culturas de Responsabilização em Educação Infantil no México [Cultures of accountability in indigenous early childhood education in Mexico]. Educacao and Realidade, 45(2), e99893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Meléndez, L. A. (2024). Meaningful ICT integration into deprived rural communities’ multigrade classrooms. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 19, 005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister-Tyrrell, M., & Pringle, E. (2021). Differentiation in an Australian multigrade classroom. In Perspectives on multigrade teaching: Research and practice in South Africa and Australia (pp. 185–212). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbetta, G. P., Chuard-Keller, P., Sorrenti, G., & Turati, G. (2023). Good or bad? Understanding the effects over time of multigrading on child achievement. Economics of Education Review, 96, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benigno, B. L., Vasconcelos, S. M. O., & Franco, Z. G. E. (2023). Educação infantil do campo: Docência em turmas multisseriadas no interior do Amazonas [Rural early childhood education: Teaching in multigrade classrooms in the hinterland of the amazon]. Cadernos CEDES, 43(119), 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix, R., & Busca, F. (2020). Competencias del Profesorado de la Escuela Rural Catalana para Abordar la Dimensión Territorial en el Aula Multigrado [Catalan rural schools teachers’ skills to face the territorial dimension in the multigrade classroom]. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana Sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educacion, 18(2), 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix, R., & Bustos, A. (2014). La enseñanza en las aulas multigrado: Una aproximación a las actividades escolares y los recursos didácticos desde la perspectiva del profesorado [The teaching in multigrade classrooms: An approach to school activities and teaching resources from teachers’ perspective]. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa, 7(3), 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bongala, J. V., Bobis, V. B., Castillo, J. P. R., & Marasigan, A. C. (2020). Pedagogical strategies and challenges of multigrade schoolteachers in Albay, Philippines. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 22(4), 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunswic, E., & Valérien, J. (2004). Multigrade schools: Improving access in rural Africa? UNESCO: International Institute for Educational Planning. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000136280 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Bunga, J. B., Olano, M. L. R., & Morga, M. R. (2025). Differentiated instruction in multigrade classrooms: Bridging theory and practice. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 11(3), 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrete-Marín, N., & Domingo-Peñafiel, L. (2022). Textbooks and teaching materials in rural schools: A systematic review. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 12(2), 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrete-Marín, N., Domingo-Peñafiel, L., & Simó-Gil, N. (2024a). Educational practices and teaching materials in spanish rural schools from the territorial dimension. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 34(2), 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrete-Marín, N., Domingo-Peñafiel, L., & Simó-Gil, N. (2024b). Teaching materials for rural schools: Challenges and practical considerations from an international perspective. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 7, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrete-Marín, N., Domingo-Peñafiel, L., & Simó-Gil, N. (2024c). Teaching materials in multigrade classrooms: A descriptive study in Spanish rural schools. Social Sciences and Humanities Open, 10, 100969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-López, J., & Figaredo, D. D. (2022). Characterisation of flipped classroom teaching in multigrade rural schools. South African Journal of Education, 42, S1–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, L. (2021a). History, context and future directions of multigrade education. In L. Cornish, & M. J. Taole (Eds.), Perspectives on multigrade teaching: Research and practice in South Africa and Australia (pp. 21–39). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, L. (2021b). Quality practices for multigrade teaching. In L. Cornish, & M. J. Taole (Eds.), Perspectives on Multigrade teaching: Research and practice in South Africa and Australia (pp. 165–184). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida Mota, C. M., da Silva, F. O., & Pacheco Rios, J. A. V. (2021). Classes multisseriadas em escolas da roça: Lócus das práticas contextualizadas pela diferença [Multigrade classes in rural schools: Locus of practices contextualized by difference]. Revista Portuguesa de Educacao, 34(2), 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Vega, L. F. (2020). Docencia en aulas multigrado: Claves para la calidad educativa y el desarrollo profesional docente [Multilateral Education: Key Words for Educational Quality and Professional Development]. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva, 14(2), 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, N., Manassero, M., & Vázquez, Á. (2020). El pensamiento creativo en estudiantes para profesores de ciencias: Efectos del aprendizaje basado en problemas y en la historia de la ciencia [Creative Thinking in Prospective Science Teachers: Effects of Problem and History of Science Based Learning]. Tecné, Episteme y Didaxis: TED, 48, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druker Ibáñez, S. (2020). El giro epistemológico: De la diversidad de los otros a la diversidad como condición del encuentro [The Epistemological Turn: From the diversity of the other to diver-sity as a condition of the encounter]. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 19(39), 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, B., & Jita, L. (2020). The rural child and the ambivalence of education in Zimbabwe: What can bricolage do? Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(9), 3873–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, A., & Subramanien, B. (2021). Teacher usage of ICT in a South African multigrade context. In L. Cornish, & M. J. Taole (Eds.), Perspectives on multigrade teaching: Research and practice in South Africa and Australia (pp. 213–241). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, C., Aktay, E. G., & Kuru, O. (2021). Improving the speaking skill of primary school students instructed in a multigrade class through cartoons. Participatory Educational Research, 8(4), 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Morante, C., Martínez, B. F., Cebreiro, B., & Casal-Otero, L. (2023). Aulas multigrado: Ventajas, dificultades y propuestas de mejora manifestadas por el profesorado de Galicia-España [Multigrade classrooms: Advantages, difficulties and proposals for improvement expressed by teachers in Galicia-Spain]. Revista Portuguesa de Educacao, 36(2), e23030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlin, P. R., & Birch, I. K. F. (1995). Preparatory survey for the development of a methodological guide for one-teacher primary schools and multigrade classes: The Australian case study. Educational Research and Perspectives, 22(1), 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Contreras, P. A., Llanquín-Yaupi, G. N., Neira-Toledo, V. E., Queupumil-Huaiquinao, E. N., Riquelme Hueichaleo, L. A., & Arias-Ortega, K. E. (2021). Prácticas pedagógicas en aula multigrado: Principales desafíos socioeducativos en Chile [Pedagogical practices in multigrade classroom: Main socio-educational challenges in Chile]. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 51, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L. T. (2023). La enseñanza de la adición con números naturales en la escuela primaria multi-grado [Teaching natural number sums in multi-grade primary school]. Educacion Matematica, 35(1), 142–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, M. M., Hus, V., Hegediš, P. J., & Domínguez, S. C. (2022). Students of primary education degree from two European universities: A competency-based assessment of performance in multigrade schools. Comparative study between Spain and Slovenia. Revista Espanola de Educacion Comparada, 40, 162–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J. T. G., Bermúdez, E. A., & Buriticá, L. P. M. (2024). Rural teachers’ meanings about teaching of decimal metric system. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 20(6), em2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalender, B., & Erdem, E. (2021). Challenges faced by classroom teachers in multigrade classrooms: A case study. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 5(4), 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaçoban, F., & Karakuş, M. (2022). Evaluation of the curriculum of the teaching in the multigrade classrooms course: Participatory evaluation approach. Pegem Egitim ve Ogretim Dergisi, 12(1), 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlberg-Granlund, G. (2023). The heart of the small Finnish rural school: Supporting roots and wings, solidarity and autonomy. In K. E. Reimer, M. Kaukko, S. Windsor, K. Mahn, & S. Kemmis (Eds.), Living well in a world worth living in for all (pp. 47–67). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, A., & Güven Demir, E. (2023). Multi-grade teaching: Experiences of teachers and preservice teachers in Turkey. The Hungarian Educational Research Journal, 13(2), 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, T. (2021). Overcoming Learning Barriers of Hutterian Students. BU Journal of Graduate Studies in Education, 13(4), 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Cilleros, M. V., Gutiérrez-Ortega, M., Morán-Antón, M., & Sánchez-Gómez, M. C. (2021). Percepción del profesorado de las aulas multigrado desde una perspectiva DAFO [Teachers’ perceptions of multi-grade classrooms from a SWOT perspective]. Revista Lusofona de Educacao, 51(51), 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinko, L., & Topolovčan, T. (2023). Područna osnovna škola i kombinirani razredni odjel: Studija slučaja. Reinkarnacija didaktičkih ideja John Deweya, Peter Petersena i Célestin Freineta u Hrvatskoj [Branch elementary school and multigrade clasroom: A case study. Reincarnation of the didactic ideas of John Dewey, Peter Petersen and Célestin Freinet in Croatia]. Acta Iadertina, 20(2), 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain, K. V. M., Heaston, A., & Kitchens, T. (1995). A multi-age grouping success story. Early Childhood Education Journal, 23(2), 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B. A. (1990). A review of quantitative research on multigrade instruction. Rural Education Quarterly, 6(2), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, B. A. (1991). A review of qualitative research on multigrade instruction. Journal of Rural Education Research, 7(2), 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, E. M., & Cheng, Y. L. (2025). Parents as allies: Innovative strategies for (re)imagining family, school, and community partnerships. Education Sciences, 15(5), 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munser-Kiefer, M., Martschinke, S., Lindl, A., & Hartinger, A. (2023). Development of self-concept in multi-grade 3rd and 4th classes. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 15(4), 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naparan, G. B., & Alinsug, V. G. (2021). Classroom strategies of multigrade teachers. Social Sciences and Humanities Open, 3(1), 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, C. P. (2023). La propuesta educativa multigrado 2005. Diseño pedagógico a partir de los retos, experiencias y aportes educativos [The 2005 multigrade educational proposal. Pedagogical design based on challenges, experiences and educational contributions]. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Rural, 1(1), 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J., Akl, E., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M., Li, T., Loder, E., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Alonso-Fernández, S. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas [The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews]. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluk, S. (1993). Comparison of academic achievement in multigrade and single-grade elementary classrooms. Journal of Christian Education Research, 2(2), 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluk, S. T. (1992). Comparison of academic achievement of students in multigrade elementary classrooms and students in single-grade self-contained elementary classrooms [Tesis de Maestría, Montana State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Psacharopoulos, G., Rojas, C. D. V., & Vélez, E. (1993). Achievement evaluation of Colombia’s “Escuela Nueva”: Is multigrade the answer? Comparative Education Review, 37(3), 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo-Rivas, M., Sierra-Martínez, S., Alonso-Ferreiro, A., García-Fuentes, O., & Zabalza-Cerdeiriña, M. A. (2024). Myths and realities of rural schools. The voice of families and teachers. Revista Electronica Educare, 28(3), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, P., Fiszbein, A., García, S., & Radinger, T. (2017). OCDE revisión de recursos escolares [OECD Reviews of School Resources: Chile 2017]. OECD Chile. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/es/publications/reports/2017/12/oecd-reviews-of-school-resources-chile-2017_g1g846ad/9789264287112-es.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Santos-Casaña, L. E. (2011). Aulas multigrado y circulación de los saberes: Especificidades didácticas de la escuela rural [Multigrade classrooms and circulation of knowledge: Specification teaching of rural schools]. Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado, 15(2), 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Shareefa, M. (2021). Using differentiated instruction in multigrade classes: A case of a small school. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 41(1), 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareefa, M., Moosa, V., Zin, R. M., Abdullah, N. Z. M., & Jawawi, R. (2020). A challenge made easy: Contributing factors for successful multigrade teaching in a small school. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 28(3), 1643–1661. [Google Scholar]

- Taole, M. J. (2020). Diversity and inclusion in rural South African multigrade classrooms. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(12), 1268–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taole, M. J. (2021). Assessment and feedback practices in a multigrade context in South African classrooms. In L. Cornish, & M. J. Taole (Eds.), Perspectives on multigrade teaching: Research and practice in South Africa and Australia (pp. 141–161). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taole, M. J. (2022). Challenges encountered by teaching principals in rural multigrade primary schools: A South African perspective. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 18(2), 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Taole, M. J. (2024). ICT integration in a multigrade context: Exploring primary school teachers’ experiences. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 9(1), 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taole, M. J., & Cornish, L. (2021). Breaking isolation in Australian multigrade teaching contexts through communities of practice. In L. Cornish, & M. J. Taole (Eds.), Perspectives on multigrade teaching: Research and practice in South Africa and Australia (pp. 95–117). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, A. A. (2020). The promise of language planning in indigenous early childhood education in Mexico [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania]. [Google Scholar]

- Tavella, G. N., & Fernández, S. C. (2023). Reflecting on a community service-learning project for English learners in Argentina from a decolonial perspective. In Decolonizing Applied Linguistics Research in Latin America (pp. 126–146). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thaba-Nkadimene, K. L., & Molotja, T. W. (2021). Critical and Capability Theories as a Framework to Improve Multigrade Teaching. In Perspectives on multigrade teaching: Research and practice in South Africa and Australia (pp. 57–70). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C., & Shaw, C. (1992). Issues in the development of multigrade schools (Vol. 172). World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk, M. M. (2019). Teachers’ voices matter: Is cooperative learning an appropriate pedagogy for multigrade classes? International Journal of Pedagogy and Curriculum, 26(2), 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, M. M. (2021). South African multigrade teachers’ implementation of cooperative learning strategies. In L. Cornish, & M. J. Taole (Eds.), Perspectives on multigrade teaching: Research and practice in South Africa and Australia (pp. 73–93). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, R., & Sabljak, M. (2020). Kombinirani razredni odjel: Socioekonomska nužnost ili pedagoški izbor? [Multigrade classroom: Socio-economic inevitability or pedagogical pick?]. Acta Iadertina, 17(2), 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenman, S. (1995). Cognitive and non-cognitive effects of multigrade and multi-age classes: A best-evidence synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 65(4), 319–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigo-Arrazola, B., & Moreno-Pinillos, C. (2025). Creative and inclusive teaching practices in multigrade schools. An ethnographic study on the use of digital media. International Journal of Educational Research, 131, 102596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidmann, L., & Fiechter, U. (2023). The didactics of autonomy in multigrade classrooms. In J. Hangartner, H. Durler, R. Fankhauser, & C. Girinshuti (Eds.), The fabrication of the autonomous learner: Ethnographies of educational practices (pp. 75–90). Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Terms | Filters Applied | Time Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERIC | (“multigrade” AND “teaching”) OR (“multigrade” AND “classes”) | Open Access, Full Text | 2019–2024 |

| Scopus | (“multigrade” AND “teaching”) OR (“multigrade” AND “classes”); alternative terms: “multi-grade”, “multiage”, “pedagogy”, “early childhood education”, “primary education” | Document type: articles; Access type: open | 2019–2024 |

| Study (Autor, Year) | Inclusion Status | Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Cornish (2021a) | Excluded (reason 1) | No access to full text |

| Cornish (2021b) | Excluded (reason 1) | No access to full text |

| Thaba-Nkadimene and Molotja (2021) | Excluded (reason 1) | No access to full text |

| Druker Ibáñez (2020) | Excluded (reason 2) | Not in line with the objective of the study |

| Tapia (2020) | Excluded (reason 1) | No access to full text |

| Tavella and Fernández (2023) | Excluded (reason 1) | No access to full text |

| Aktan (2021) | Excluded (reason 2) | Not in line with the objective of the study |

| Castillo-López and Figaredo (2022) | Excluded (reason 1) | No access to full text |

| Du Plessis and Subramanien (2021) | Excluded (reason 1) | No access to full text |

| Taole (2021) | Excluded (reason 1) | No access to full text |

| Taole and Cornish (2021) | Excluded (reason 1) | No access to full text |

| Van Wyk (2021) | Excluded (reason 1) | No access to full text |

| Category | General Description | Examples or Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational models | Structural configuration of the multigrade classroom according to context, enrolment, and available resources. | Single classrooms in the Rural Grouping Center (CRA) and combined classrooms in the incomplete CEIP. |

| Pedagogical methodologies | Strategies used to cater for the heterogeneity of the student body. | Cooperative learning, project-based learning, jump-jump, and Escuela Nueva (New School) model. |

| Teacher training | Level of initial and ongoing preparation of teachers to deal with the multigrade model. | Lack of specific training and need for adapted plans. |

| Strengths of the model | Pedagogical, social, and organizational opportunities of the multigrade classroom. | Individualized attention, autonomy, peer learning, and flexibility. |

| Challenges and barriers | Constraints to effective implementation of the model. | Teaching overload, shortage of resources, and professional isolation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ares-Ferreirós, M.; Álvarez Martínez-Iglesias, J.M.; Bernárdez-Gómez, A. Challenges and Opportunities of Multi-Grade Teaching: A Systematic Review of Recent International Studies. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081052

Ares-Ferreirós M, Álvarez Martínez-Iglesias JM, Bernárdez-Gómez A. Challenges and Opportunities of Multi-Grade Teaching: A Systematic Review of Recent International Studies. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081052

Chicago/Turabian StyleAres-Ferreirós, Martina, José María Álvarez Martínez-Iglesias, and Abraham Bernárdez-Gómez. 2025. "Challenges and Opportunities of Multi-Grade Teaching: A Systematic Review of Recent International Studies" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081052

APA StyleAres-Ferreirós, M., Álvarez Martínez-Iglesias, J. M., & Bernárdez-Gómez, A. (2025). Challenges and Opportunities of Multi-Grade Teaching: A Systematic Review of Recent International Studies. Education Sciences, 15(8), 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081052