1. Introduction

Initial training for teachers of preschool and the first and second cycles of basic education in Portugal begins with a degree in Elementary Education, as established in the Legal Framework for Professional Qualifications for Teaching in Preschool Education and Basic and Secondary Education (

Decreto-Lei n.º 9-A/2025, 2025). It should be noted that the first cycle of basic education corresponds to the first four years of compulsory schooling for children, and the second cycle refers to the following two years. Therefore, the training mentioned above relates to the initial training of teachers for the first six years of the twelve years of compulsory education.

The degree in Elementary Education is a first cycle of training lasting three years, which aims to guarantee a foundation and global scientific and human training for the area of teaching, based on a common body of knowledge. The curricular structure is set out in Article 13 and indicates that the degree is awarded with a minimum of 180 credits, distributed among the different training components, which are: (a) Teaching area: minimum of 125; (b) General educational area: minimum of 15; (c) Specific didactics: minimum of 15; (d) Initiation to professional practice: minimum of 15. It should also be noted that there is a fifth training component, the ‘Cultural, Social and Ethical Area’, which is provided in the context of the other training components (Article 7). This means that it is transversal, and there does not appear to be any dedicated or objective space for problematizing this knowledge, which is argued to be the hallmark of teaching.

It should also be noted that the teaching area includes four structuring ‘skills’, and a minimum of 30 credits is required for each (Portuguese; Mathematics; Natural Sciences and History of Portugal; Expressions). As a rule, candidates for this degree enroll through a national competition and must have completed their 12th year of schooling or equivalent, with a minimum classification of 95 points (on a scale of 0 to 200), and entrance exams are required in the areas of Portuguese and Mathematics. They may also be admitted through other special conditions previously defined by the higher education institutions.

It should be noted that the training is carried out in higher education institutions (public or private), and that these institutions are free to organize the course and define the respective entry conditions, provided that the requirements set out in the Legal Framework for Professional Qualifications for Teaching in Preschool Education and Basic and Secondary Education (

Decreto-Lei n.º 9-A/2025, 2025) are taken into account, and that the Higher Education Assessment and Accreditation Agency, in conjunction with the Ministry of Education, Science and Innovation, has authorized the respective functioning.

This degree subsequently gives access to the second cycle of studies, i.e., the professionalizing master’s degrees that confer a professional qualification for teaching in Preschool Education and/or in the first and second cycles of Basic Education.

Considering the importance of ethics in the practice of teaching, and the fact that it is legally enshrined in initial teacher training, a study entitled “Ethics in the initial training of educators/teachers—The view of undergraduate students in Elementary Education” was conducted in two public higher education institutions in Portugal. The research, which was predominantly quantitative in nature, had the general objective of identifying the perception of undergraduate students in Elementary Education at two Portuguese higher education institutions regarding the approach to the ethical dimension in their courses. In this article, and within the framework of the research project, the aims are: (i) to determine whether the study plan for the Elementary Education degree adequately addresses ethical issues; (ii) to assess whether ethics should be taught as an integral part of the study plan; (iii) to gather possible suggestions and ways of improving the ethical approach in the Elementary Education degree. The article is structured as follows: a brief literature review is provided, followed by an explanation of the methodological approach, presentation and discussion of the results, and, finally, the concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review

The word ethics comes from the Greek

ethos, which means custom, habitual way of acting, principles, values and character. Morals, on the other hand, come from the Latin

mos, which refers to duties, norms, and standards of behavior (

Baptista, 2005;

Carvalho et al., 2011;

Paramo Bernal, 2018;

Vargas Guillén et al., 2018).

In contemporary times, the word ethics has become widely discussed in the media, and it is now common to hear it in the public sphere, across various contexts, and for different reasons. Generally, it reflects the life choices people make, associating it with values such as goodness, honesty, justice, truth, and freedom. It is also frequently associated with the word “morality,” and, as a rule, the two terms are used almost interchangeably in everyday language. However, as previously noted, ethics relates more to reflection and the questioning of principles and rules, while morality is more closely tied to the norms and social practices of a specific context (

Paramo Bernal, 2018;

Vargas Guillén et al., 2018).

Cuadros-Contreras (

2020) points out, while recognizing the possibility or necessity of such resources, that ethics is not merely a matter of codes or regulations. It should not be understood as a simple practice aimed at regulating our actions. According to the same author, and regardless of good intentions, it should also not be reduced to a safeguard against destructive tendencies, focused on risk prevention, or on tools designed to protect against the danger of making a mistake or doing something wrong. In other words, ethics should not be confined to a purely defensive conception, as a kind of technique or management of care and prevention. As a counterpoint,

Cuadros-Contreras (

2020) argues that ethics should have a strong affirmative dimension, the pursuit of happiness and the search for the good, which implies a sound analysis of human life and has implications for how ethics is taught (

Cuadros-Contreras, 2020). In this view, the importance and necessity of critical thinking that connects ways of life with science, ethics, culture, and political issues is reinforced, fostering reflection on the present and the ability to imagine and anticipate the future of a society we hope will be more humanized and sustainable (

Raupp, 2022).

Dixon (

2015) goes further by describing ethical competence “(…) as a collection of skills that require development and practice for their exercise to maturity (…)” (p. 75).

Returning to the issue of regulatory documents in the field of ethics, they often refer to the medical sciences, without considering that ethical care should be taken into account in research in other areas, namely, the social sciences. According to the author, this absence is even more pronounced in research involving children (

Fernandes, 2016). It should be emphasized that ethical considerations should prevail not only in research, but also in practice, namely in teaching practice, which is why it is argued, in line with the Legal Framework for Professional Qualifications for Teaching in Preschool Education and Basic and Secondary Education, that ethics should be integrated from the outset into the initial training of future teachers.

Higher education institutions play a central role in the creation and dissemination of knowledge, and teacher training is at the forefront of this work, with the potential to make a real difference for students (

Bulcão et al., 2024;

Moodley & Chetty, 2024;

Teke, 2021). Ethics instruction in initial teacher training helps future teachers develop a strong moral and ethical foundation, which is crucial for their professional practice. This foundation supports teachers in making ethical decisions and acting as role models for their students (

Göçen & Bulut, 2024;

Smith, 2014). It also prepares student teachers to face the ethical dilemmas they will encounter in their professional lives, including the development of a moral vocabulary and the critical thinking skills necessary to navigate complex ethical situations (

Davies & Heyward, 2019;

Göçen & Bulut, 2024). It fosters the ability to reflect on and address ethical issues within the specific sociocultural contexts of their teaching environments (

Davies & Heyward, 2019). The integration of ethics into the curriculum helps future teachers see the relevance of ethics in all areas of their professional practice, from classroom management to interactions with colleagues and the broader community (

Walters et al., 2018). Ethics instruction also promotes the development of ethical leadership among teachers, enabling them to cultivate ethical cultures within their schools and districts (

Smith, 2014).

According to

Loss et al. (

2025), the integration of ethics into initial teacher education offers several benefits: the strengthening of interpersonal relationships, the development of self-reflection, the valuing of the human dimension of teaching, and the promotion of ethical educational cultures. These benefits emerge from the participants’ own narratives and are closely linked to concrete formative practices—such as projects, pedagogical activities, and university-based interactions—which support the development of an ethical stance in professional practice.

Bolívar and Pérez-García (

2022) argue that integrating ethics into initial teacher education significantly contributes to the development of a strong professional identity grounded in moral commitment and public responsibility. The main benefits identified include the valuing of the ethical dimension of teaching, the promotion of professional autonomy, resistance to bureaucratic and technocratic logics, and the reinforcement of the social legitimacy of the teaching profession. These benefits result from building critical ethical awareness throughout teacher education, fostering more reflective, committed, and socially responsible pedagogical practices.

No studies were identified that reported drawbacks to the approach to ethics in initial teacher training. However,

Walters et al. (

2018) warn of potential difficulties. Students may resist ethics education, finding it less engaging or relevant compared to other subjects that focus on practical skills. The inclusion of ethics in the curriculum can also be constrained by limited time and the need to cover a wide range of other essential topics; the complex nature of ethics education requires significant time and effort to teach effectively, which can be challenging within the already packed schedules of initial teacher training programs.

It should be noted that various studies highlight the importance of ethics being present in initial teacher training, both as a cross-cutting theme and as a specific curricular unit, reflecting the idea that, in a school context, education cannot be separated from ethics (

Bazurto-Barragán & Higuera-Ramírez, 2021;

Bolívar & Pérez-García, 2022;

Davies & Heyward, 2019;

Göçen & Bulut, 2024;

Leite et al., 2022;

López-Calva, 2022;

Loss et al., 2025;

Martínez Martín & Carreño Rojas, 2020;

Walters et al., 2018). It should also be emphasized that it is essential for future teachers to receive ethical training, based on the assumption that they will intentionally contribute to the ethical development of others (

De Moura Cavalcanti et al., 2022).

An international comparative study on ethics education in initial teacher training programs in five OECD countries (

Walters et al., 2018) revealed that no institution offered curricular units or modules dedicated exclusively to ethics, although the topic was addressed transversally, with varying degrees of incorporation.

Some authors also argue that it is not just a matter of curriculum. People’s behavior throughout their lives ultimately shapes who they are as professionals. Other aspects can also make a difference, such as the teacher, who should serve as a strong point of reference for building contexts of coexistence and learning, promoting initiative, responsibility, respect, and civic participation (

Bolívar & Pérez-García, 2022;

Cronqvist, 2020;

Loss et al., 2025;

Martínez Martín & Carreño Rojas, 2020).

Reimão (

2013) even argues that teachers have a responsibility not only to act ethically, but also to educate their students ethically, fostering “wise and useful knowledge” rather than merely “useful knowledge.” Ethics is understood as one of education’s constitutive dimensions, since educating means promoting a way of living and understanding life. Teachers, as professionals, become “travelling companions” and are therefore moral subjects who embody ethics and serve as responsible references, models of transformative balance (

Reimão, 2013).

We are living in changing times in which human action is centered on the Self, and it is important to reflect both in action and on action in a conscious way, valuing the Other. It is essential to recognize that the singularity of isolated acts must be reconciled with the rights and freedoms of the Other, co-constructing societies grounded in greater justice, where the common good prevails over individualism. In this sense, ethics is committed to this relationship insofar as it presupposes the mutual recognition of people, positioning itself through concrete actions and decisions, at the intersection between universality and the values that emerge from lived experience (

Carvalho et al., 2011).

So, if education is a practice and an action intrinsically connected to the existence of the Other and, therefore, to the human condition, it implies a forward-looking responsibility that calls for education professionals who are capable of understanding that ethics arises, first and foremost, from an awareness of the Self as a sensitive being in coexistence with the Other, and that this relationship involves the dimension of time and human action (

Carvalho et al., 2011).

Cuadros-Contreras (

2020) argues that none of this is possible without a strong sense of formation and the development of a common affective and evaluative sensibility that accompanies us from early childhood to the highest levels of education, a shared sensibility that includes not only those close to us, but also those who are very different from us.

In this regard, it should be emphasized that the National Education Council (Conselho Nacional de Educação—Portugal), in Recommendation No. 3, published in April 2024, explicitly highlights the importance of the Education Sciences. Its aim is to develop various skills and literacies, advocating for solid initial training that enables the profession to be learned in its multiple dimensions, namely, intellectual, relational, technical, investigative, ethical, social, cultural, and emotional. To achieve this, the Council proposes training in: (i) the existence of specific professional knowledge for teaching; (ii) the vision of the teacher as a professional; (iii) the need for training that considers the multidimensionality and scope of the profession (

Recomendação n.º 3/2024 do Conselho Nacional de Educação, 2024).

The literature review reveals a consensus on the relevance of ethics in the teaching profession and the importance of including it in teacher training. Nevertheless, several authors emphasize that little is known about how students in initial teacher training are actually being prepared to address ethical issues, to confront the ethical challenges of contemporary teaching, and, in particular, about trainees’ conceptions of these issues (

Maxwell et al., 2016;

Paakkari & Välimaa, 2013). The few studies available tend to focus on small samples, employ qualitative methods, address specific dimensions of ethics, and consider a single training context (

Cronqvist, 2020;

Darabi Bazvand, 2023;

Karataş et al., 2019;

Loss et al., 2025;

Macedo & Caetano, 2017;

Paakkari & Välimaa, 2013). Within this framework and given the scarcity of studies on this topic, the research project “Ethics in initial teacher training—The view of undergraduate students in Elementary Education” was designed and implemented, as explained below.

3. Materials and Methods

The study was carried out in two Portuguese higher education institutions located in the interior of Portugal: one in the northern region (the Bragança Polytechnic University—PU_B) and the other in the Alentejo region (the Portalegre Polytechnic University—PU_P). The research project, including the data collection instrument, was previously submitted for review and approved by the PU_B Ethics Committee (reference number 520494).

Regarding the methodological approach and considering the objectives of the study and the research questions, a quantitative methodology was chosen. This approach was selected to develop a systematic research process capable of aggregating a wide range of questions, with the aim of obtaining broader information about individuals and establishing relationships between variables (

Sá et al., 2021).

In this article, and as part of the wider research project, the objectives, based on a comparison between two higher education institutions, are: (i) to determine whether the study plan for the Elementary Education degree adequately addresses ethical issues; (ii) to assess whether ethics should be taught as an integral part of the study plan; (iii) to gather possible suggestions and ways of improving the ethical approach in the Elementary Education degree course.

The data collection instrument used was a questionnaire, developed from scratch by the authors, made available for online completion, and directed to 252 students who, in the academic year 2023–2024, were enrolled in the Elementary Education degree at two higher education institutions (PU_B and PU_P). The questionnaire is organized into four sections: I—Socio-demographic Characterization, II—Study Plan, III—Ethical Issues in the Educational Context, and IV—Recommendations. It should be noted that this choice was based on the understanding that the questionnaire is an appropriate instrument for collecting information, consisting of a set of statements or questions through which the participants can freely express their ideas, information, and suggestions. It is also an instrument that reflects the research objectives through measurable variables, facilitating the organization and control of data and allowing information to be collected in a rigorous manner (

Freixo, 2012).

Once constructed, the questionnaire was made available online via the Google Forms platform for a pre-test, and no difficulties were identified in understanding the questions or completing the form. Subsequently, the final version was made available to all Elementary Education undergraduate students at PU_B and PU_P during April and May 2024.

Cronbach’s α coefficient was used to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire, which yielded an overall value of 0.86, indicating good internal consistency.

The data resulting from the responses to the closed questions were statistically processed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 29, IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) software and involved the use of descriptive analysis techniques focused on the presentation of frequencies and means (tables and graphs). Non-parametric statistical analysis techniques were also used, using appropriate statistical tests for comparing nominal and ordinal scale variables. To check for statistically significant differences (at a 5% significance level), the Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the mean ranks of an ordinal qualitative variable between two independent groups (the higher education institutions), and the Chi-Square test was applied to compare two nominal scale variables.

4. Results

Of the total 252 students enrolled in the Elementary Education degree program at the two higher education institutions (PU_B and PU_P), 141 responded to the questionnaire, corresponding to an overall response rate of 56% approximately. At PU_B, there were 184 students, of whom 85 responded (46.2%). At PU_P, 56 out of 68 students responded, representing a response rate of 82.4%.

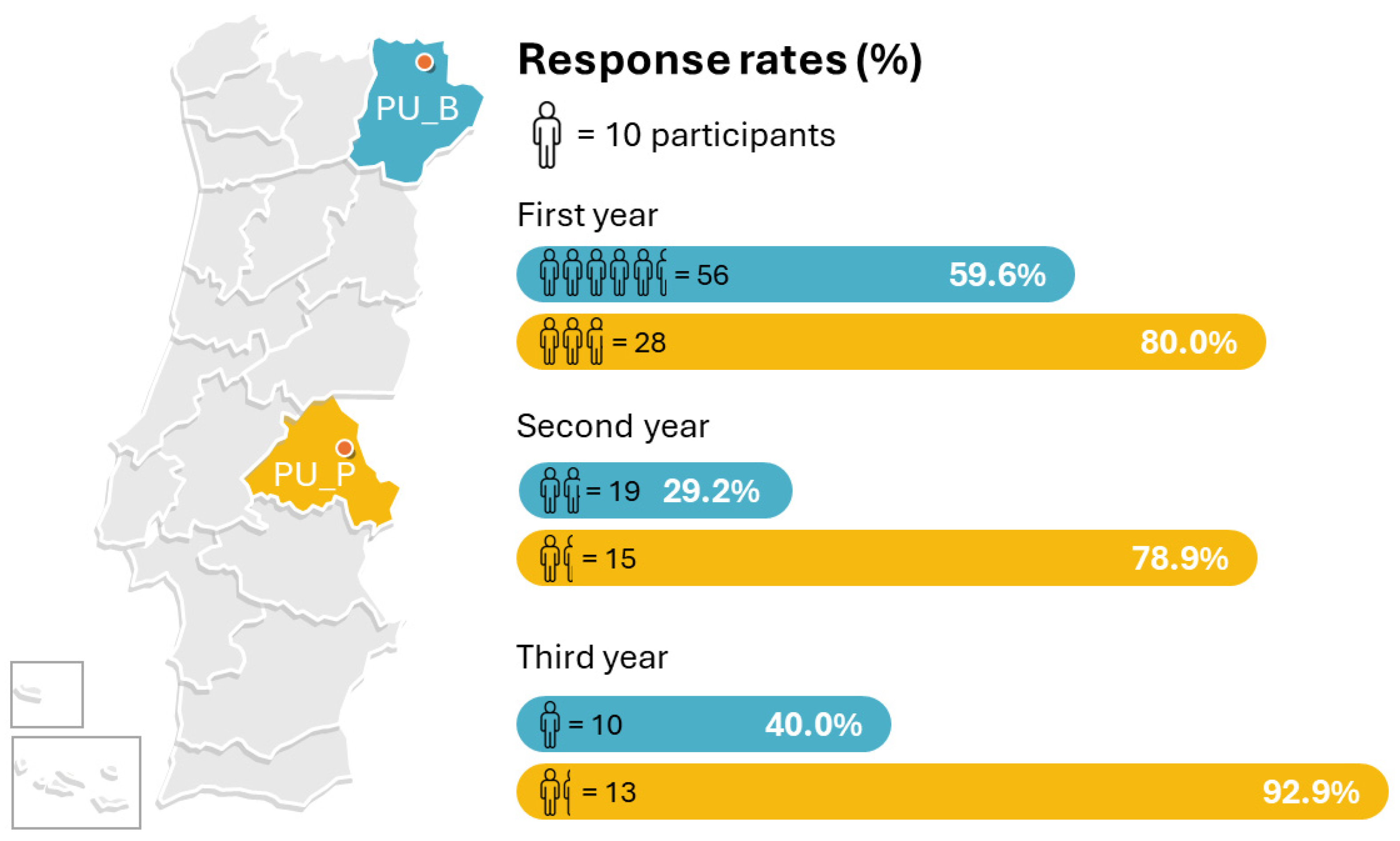

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the response rate to the questionnaire survey among students at each institution, according to the year of study. Overall, the response rate was higher among students at PU_P across all three academic years. At PU_B, the response rate was highest among first-year students. However, it should be emphasized that the total number of students enrolled at each institution during the study period differed considerably, with PU_B having approximately 2.7 times more students.

Figure 1 shows that, at both institutions, the majority of participants in the study were first-year students (59.6%), which was also the year with the highest overall enrollment. Of the total 141 participants, 24.1% were in their second year, and 16.3% were in their third year.

With regard to gender, 95.7% of the participants were female, 2.8% were male, and the remainder chose not to answer.

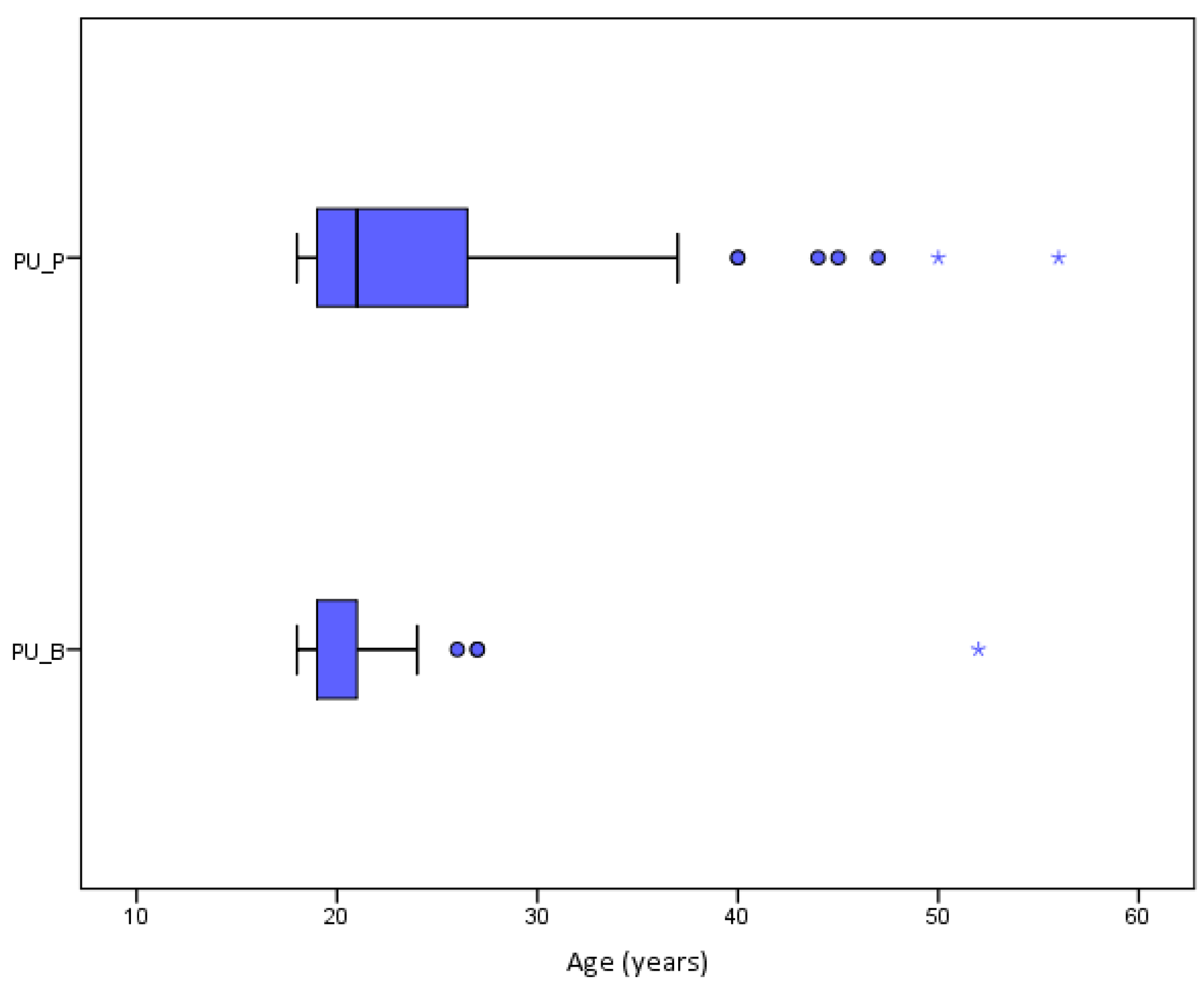

The students’ ages ranged from 18 to 56, with a mean age of 22.

Figure 2 shows the age distribution by institution, revealing the presence of outliers, that is, ages significantly different from the rest (more frequent at PU_P), which naturally increases the mean age at each institution (

and

). The data also show that the age distribution at PU_P is more dispersed: 50% of students were 21 or younger, compared to 75% at PU_B.

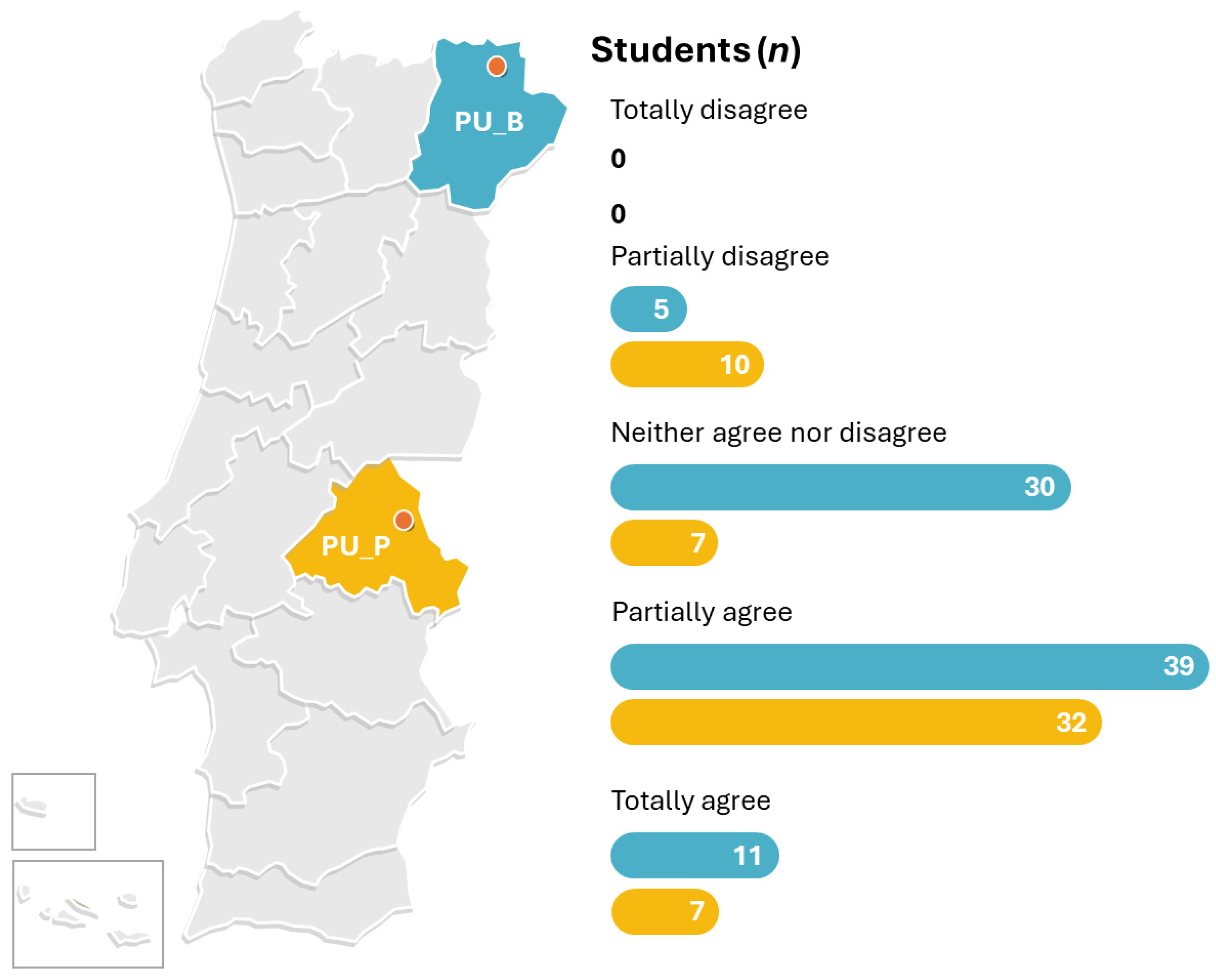

When asked whether their degree program adequately addresses ethical issues, a significant percentage of students at PU_B (35.3%) reported that they neither agreed nor disagreed, compared to a much smaller percentage at PU_P (12.5%). However, the majority of students from both institutions (PU_B: 58.8%, PU_P: 69.6%) either partially or fully agreed with how ethical issues are addressed in their degree program (

Figure 3).

Although there are some differences between the two institutions in the distribution of response frequencies across the five categories, the statistical measures presented in

Table 1 show similar values overall in terms of the mean, median, and response dispersion.

The similarity in the statistical measure values suggests that the difference in students’ mean ranks regarding the approach to ethical issues in their degree programs is not statistically significant. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney test confirms this at the 5% significance level (

,

), indicating that students’ opinions on whether their study plan adequately addresses ethical issues are not influenced by the institution they attend. The effect size associated with the test (

) reveals a small effect, that is, the magnitude of the difference between students’ opinions at the two institutions is minimal (

Table 2).

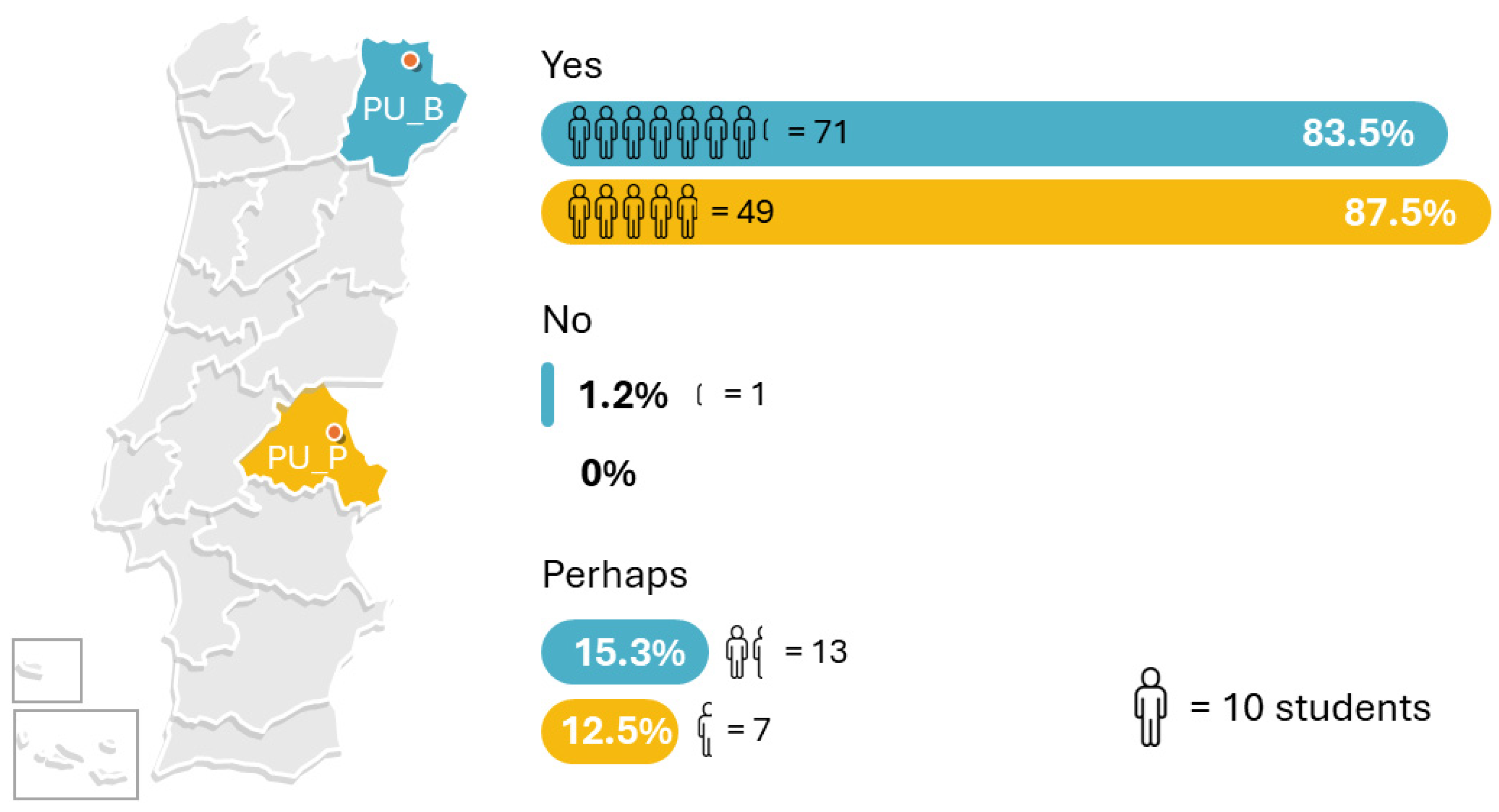

Building on this, students were asked whether they believed ethics should be included in the study plan of the Elementary Education degree. The majority (85.1%) responded affirmatively. Only one student (0.7%) answered negatively, while 14.2% selected “Perhaps”. This trend was consistent across both higher education institutions, with more than 83% of students at each responding in the affirmative (

Figure 4).

The non-parametric Chi-Square test was used to assess whether a statistically significant association exists between the inclusion of ethics in the Elementary Education degree program and the higher education institution attended. To ensure the test validity—specifically, to maintain fewer than 20% of cells with expected frequencies below five—the “No” and “Perhaps” response categories were merged. The distribution of responses is presented in

Figure 4. The results showed no statistically significant association between the variables under analysis at the 0.05 significance level (

;

). Furthermore, the effect size, calculated using Cramér’s V (

), indicates a very weak association between the variables, consistent with the thresholds proposed by

Cohen (

1988).

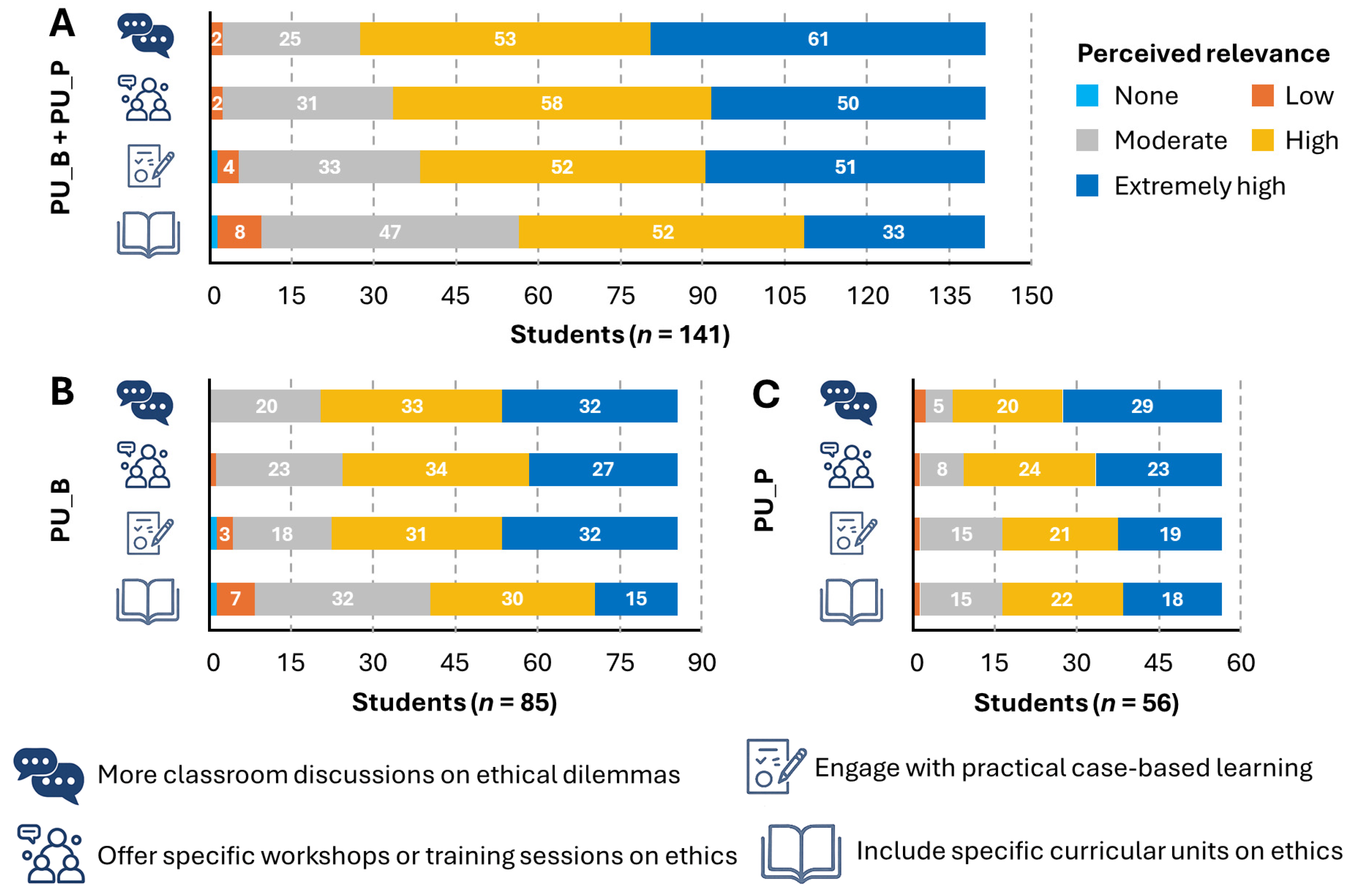

When asked about the integration of different strategies to improve the ethical approach in the Elementary Education Degree program, the results shown in

Figure 5 were obtained.

As shown, the most highly valued strategies, based on the highest number of responses in the “5—Extremely high” and “4—High” categories, were “More classroom discussions on ethical dilemmas”, “Engage with practical case-based learning”, and “Offer specific workshops or training sessions on ethics”. The strategy “Include specific curricular unit on ethics” showed greater dispersion in responses compared to the other strategies, with a more significant number of responses falling in the “4—High” and “3—Moderate” categories.

An analysis by institution attended shows some distinct patterns (

Figure 5B,C).

To assess the differences in students’ mean ranks regarding ways to improve the ethical approach in the degree program were statistically significant, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was applied. The results indicated a statistically significant difference at the 5% significance level for the strategy “Include specific curricular unit on ethics” and a marginally significant difference (0.05 ≤

p < 0.10) for the strategy “More classroom discussions on ethical dilemmas,” as the

p-value was very close to 0.05 (

Table 3). The results of the effect sizes indicate that the magnitude of the differences in the degree of importance attributed by the students to each of the four situations analyzed is low.

Students attending PU_P assigned a higher degree of importance to the strategies “Include specific curricular unit on ethics”, “Offer specific workshops or training sessions on ethics”, and “More classroom discussions on ethical dilemmas”. In contrast, students attending PU_B placed the greatest importance on the strategy “Engage with practical case-based learning” (

Table 4).

5. Discussion

The results suggest that the majority of students believe the study plan of their degree program adequately addresses ethical issues. It is important to emphasize, however, that none of the higher education institutions include curricular units specifically dedicated to ethics within the study plans of the programs in question. Thus, the overall trend appears to align with findings from previous research, which concluded that although no standalone curricular units or modules on ethics are offered, the topic is nevertheless addressed to some extent (

Cristi & García, 2018;

Walters et al., 2018). Even so, a notable percentage of students did not share this view, suggesting that the current approach may warrant reconsideration and may not fully meet the expectations of all students. Several studies support the idea that ethics could occupy a more prominent role within the curriculum (

De Moura Cavalcanti et al., 2022;

Macedo & Caetano, 2017;

Moodley & Chetty, 2024;

Ordine, 2023). Despite some divergent trends in student responses, as discussed above, no statistically significant differences were found based on the institution attended.

The students’ position was reinforced when they were asked whether ethics should be taught as part of the study plan for a degree in Elementary Education. The majority of participants, again with no statistically significant differences based on the institution attended, affirmed the importance of this knowledge and recognized its relevance within the curriculum. These perspectives align with

Macedo and Caetano (

2020), who argue that training models must be rethought and redefined, given existing gaps in this field of knowledge. Ethics, they contend, must be integrated into the core training components and granted appropriate curricular space, rather than allowing technical and scientific knowledge to the prioritized at the expense of humanistic knowledge that fosters critical thinking (

Bulcão et al., 2024;

Ordine, 2023). The materialization of these aims must be anchored in initial training that treats ethics not as a superficial element, but as a foundational dimension or reflection, on the premise that future teachers have the right to receive quality education: that is, to be well educated and educated for the good, which necessarily implies the presence of an explicit ethical component (

Ordine, 2023). Similarly,

Moodley and Chetty (

2024) emphasize that this should be a concern of higher education institutions, particularly regarding the mobilization of teachers’ knowledge to shape and guide ways of being and acting in the world. In sum, the results are consistent with several of the aforementioned studies that underscore the importance of ethics in initial teacher education, whether integrated transversally or delivered as a dedicated curricular unit (

Bazurto-Barragán & Higuera-Ramírez, 2021;

Bolívar & Pérez-García, 2022;

Leite et al., 2022;

López-Calva, 2022;

Martínez Martín & Carreño Rojas, 2020;

Walters et al., 2018).

It is worth noting that when asked how to improve the approach to ethics in Elementary Education degrees, participants valued multiple strategies, with the majority considering the top two categories of relevance. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the integration of a specific curricular unit on ethics received the lowest level of importance

1. This finding aligns with previous studies suggesting that the inclusion of ethics within curricular units may not be sufficient on its own (

Bazurto-Barragán & Higuera-Ramírez, 2021;

Bolívar & Pérez-García, 2022;

Cronqvist, 2020;

Leite et al., 2022;

Martínez Martín & Carreño Rojas, 2020). It should also be noted that the legal framework in Portugal stipulates that training in the “Cultural, Social, and Ethical Area” must be embedded within other training components (

Decreto-Lei n.º 9-A/2025, 2025). However, the results of the statistical tests revealed significant differences based on the institution attended, indicating the presence of distinct trends. Notably, students at PU_P placed greater emphasis on the integration of a specific curricular unit.

The most emphasized strategy for improving the ethical approach in the Elementary Education degree was the inclusion of more classroom discussions on ethical dilemmas. This finding is consistent with previous studies that highlight the importance of ethics education in fostering intellectual knowledge, moral decisions, and the development of teaching skills, encouraging reflection and the problematization of values inherent to the teaching profession (

Bulcão et al., 2024;

Macedo & Caetano, 2020). Similarly,

Loss et al. (

2025) emphasize the role of listening, dialogue, problematization, and critical reflection in ethical development. Several authors further emphasized the need to view teaching as a future-shaping profession that must be grounded in ethical practice (

Bazurto-Barragán & Higuera-Ramírez, 2021;

Bolívar & Pérez-García, 2022;

Leite et al., 2022;

López-Calva, 2022;

Martínez Martín & Carreño Rojas, 2020).

Freire (

2005) adds that the teaching role extends beyond delivering content to promoting thought, “teaching to think right.” Teachers must not shy away from ethical rigor; rather, their scientific competence must be grounded in both scientific and ethical integrity (

Freire, 2005). The statistical tests revealed marginally significant differences based on the institution attended, suggesting that once again, students from PU_P placed greater emphasis on this particular approach.

The inclusion of “Engage with practical case-based learning” was also considered a valuable way to improve the ethical approach in the Elementary Education degree. It can be inferred that, alongside the strategies mentioned above, students value practical, experience-based knowledge, though not disconnected from theoretical knowledge, as practice itself can challenge and reshape the theories and patterns that underpin action (

Dixon, 2015;

Macedo & Caetano, 2017).

Morin (

2002) stresses that this kind of thinking enables a simultaneous understanding of the text and its context, the individual, and their environment, the local and the global, integrating multidimensional perspectives and synthesizing complexity, that is, the conditions of human behavior, which are inherently linked to the human relationships embedded in teaching praxis. Within this process, it is essential to create opportunities for critical and grounded reflection on practice and action (

Bazurto-Barragán & Higuera-Ramírez, 2021;

Bolívar & Pérez-García, 2022;

Bulcão et al., 2024;

Cronqvist, 2020;

Leite et al., 2022;

Loss et al., 2025;

Martínez Martín & Carreño Rojas, 2020).

Regarding these last two strategies for improving the ethical approach, practical cases, and workshops or training sessions, no statistically significant differences were found based on the institution attended.

It is important to emphasize that although the four strategies for improving the ethical approach were ranked in hierarchy, the majority of students rated all of them within the top two categories of relevance.

It is widely acknowledged that the educational process is a collective responsibility. However, it is also recognized that current social and material conditions tend to prioritize the exact sciences while marginalizing the humanities and social sciences. In this context,

Ordine (

2023) argues that, in today’s globalized world, memories of the past, humanistic disciplines, free inquiry, the arts, critical thinking, and the civic horizon that should guide and inspire all human activity are gradually being erased. According to the author, this undermines essential knowledge that forms the foundation for learning how to think and understand human nature, knowledge that can transform a dull, unreflective existence into a vibrant and engaged life, guided by curiosity about human concerns. This, Ordine insists, is the true commitment of a teacher.

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Future Directions

Returning to the objectives defined at the outset, it can be concluded that students generally perceived the study plan of their degree as adequately addressing ethical issues, although not all opinions aligned. It was also evident that the majority of students, consistent with findings from other studies, believed ethics should be an integral part of the curriculum, identifying different ways to strengthen its presence in the Elementary Education degree program, not necessarily through the inclusion of a dedicated ethics course. These findings highlight the importance of cultivating in students (as future teachers) a genuine engagement not only with the construction of knowledge, but also with its social, affective, and ethical dimension, through a praxis grounded in human relationships, dialogue, and a commitment to dignity and respect for the Other. There is a clear need to (re)think the structure of study plans, or at least the content and approaches of existing courses, to ensure that ethics is meaningfully and holistically embedded in teacher education, particularly in the ways perceived as most relevant by students themselves.

It should be emphasized that, from a comparative perspective, statistically significant differences were found regarding the integration of a specific ethics-related course, as well as marginally significant differences concerning the inclusion of more classroom discussions on ethical dilemmas as strategies to enhance the ethical approach. These differences highlight particularities based on the higher education institution attended by the study participants. In the future, it would be essential to conduct further analyses by cross-referencing additional variables to identify other statistically significant patterns that could enrich the findings and provide a deeper understanding of the educational contexts involved.

We believe that this study is relevant given the limited number of investigations in this field, despite the widely recognized relevance of the topic, as highlighted in the literature review. Therefore, a key strength of this research is its contribution to expanding scientific knowledge; the findings may offer valuable insights for revising initial teacher training curricula, with the aim of enhancing the integration and treatment of ethical issues. Additionally, as highlighted in the literature review, existing studies often adopt qualitative methodologies, have small sample sizes, and focus on specific contexts. In this regard, another noteworthy strength is the methodological design employed in this study—predominantly quantitative and based on a questionnaire—which allowed for a broader analysis of the situation within two higher education institutions and included a substantial proportion of the student population.

However, certain limitations must be acknowledged. Despite the considerable number of participants, data were collected from only two institutions, both located in the interior regions of the country. While the findings may offer insights applicable to Elementary Education degrees at institutions located in different geographical contexts, this geographic concentration constrains the generalizability of the results.

In future studies, this research could be further developed by incorporating a more qualitative methodological approach. It would also be beneficial to collect data from faculty members in these programs, enabling a triangulation of perspectives. Additionally, replicating the study with students enrolled in Elementary Education degrees at other higher education institutions, particularly those located in different geographical regions, would help broaden the scope and deepen the understanding of the findings.