“It Required Lots of Energy from Me and I Didn’t Feel I Received Much in Return”: Perceptions of Educarers Who Dropped Out of the Ministry of Education’s Training Course Towards Their Dropping Out

Abstract

1. Introduction

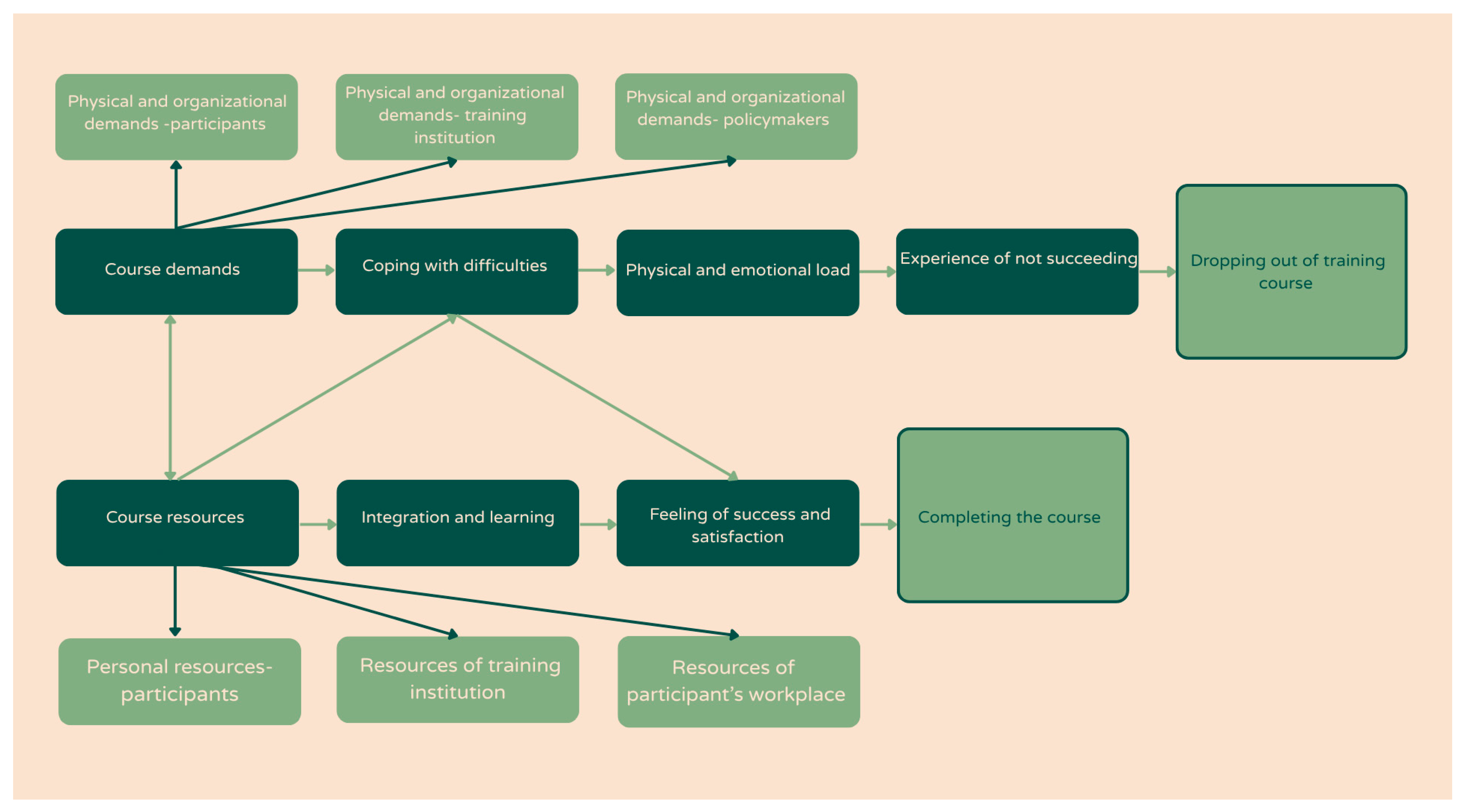

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Early Childhood Education Systems in Israel—Characteristics and Development

2.2. Challenges in the Early Childhood Education System in Israel

2.3. Training of Educarers Around the World and in Israel

2.4. Dropout from Work and Professional Training Courses in the Field of Early Childhood Education

3. Research Method

3.1. Participants

3.2. Research Instruments

3.3. Research Process and Ethical Issues

3.4. Analysis of the Findings

4. Findings

4.1. Conformance with and Reference to Previous Experience and Knowledge

I think there is a very, very big difference between someone who came to the course as a beginner, someone who just started working in preschools, and someone who really—really, I’m not just full of myself, okay?—but with so many years of experience and I’ve worked with the whole age range. There’s… a big difference.

I had a hard time with the discrepancy between girls who have been working in the system for a year, while I’ve been in the system for almost 30 years, and we can’t be the same, it’s just not correct. I really know the work… Maybe if, let’s say, I was learning in a smaller class, with women like me who have more experience, then it would be easier for me to listen, hear, and share… I think it could have helped me.

4.2. The Challenges of Studying After Work Hours

We come after an exhausting day of work; the children are boisterous. They are two years old, they are that age, you know, when they are testing limits, they are not easy, they are very challenging. And then to come to study after a day like that. I thank God that I didn’t fall asleep in class.

I’m not talking about caregivers who don’t have children, it’s easy for them, they can do it at night, in the afternoon, they are always available. But for those who have children, it’s much more complicated. Also, it’s until 9:30 at night. Listen, it’s not easy, you need to find a babysitter… it’s not easy.

4.3. The Need for Practical Tools Versus Studying Educational Theories

First of all, maybe a little less theory. It was too theoretical… and more, more practical things… Then more tools for the caregiver, … for how to behave with them, how to reach them… The theories of Piaget, Erikson, you have to know, but not in such depth.

Application in the field is much more effective than learning in the classroom… More application in the field, not what Freud would say… All kinds of things that are nice to know in principle, but… less effective for us in the field. More… of the practical aspect.

If I were planning this training course, I would at least start by answering some very basic things that would, I don’t know, straight away feel really important from the beginning, and maybe then get to some theoretical content that they think is relevant.

4.4. The Lack of Personal and Professional Support Mechanisms

I would like to have help with the assignments, and God willing, my biggest dream is that I will succeed, and that I will at least have this one certificate in my hand… I was a little upset because there was no one to help me and no one to give me the tools… I don’t mean that, God forbid, I was some kind of dimwitted person or something, just that there were things that were new to me and that I hadn’t learned.

I guess I’m undiagnosed ADHD… It was hard for me. Let’s say in class, I somehow managed… But when it came to all sorts of work, homework, studying for tests, preparing a summary paper, here, wow, it came out big time… For me, it was too much… I didn’t submit the work because I wasn’t able to do it.

5. Discussion

6. Practical Recommendations

7. Research Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achituv, S., & Hertzog, E. (2020a). Partners or managers? Mothers or bosses? Conflicting identities of Israeli daycare managers. Early Child Development and Care, 190(12), 1931–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achituv, S., & Hertzog, E. (2020b). ‘Sowing the seeds of community’: Daycare managers participating in a community approach project. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 48(6), 1080–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achituv, S., & Hertzog, E. (2021). “Before you invite guests, you have to clean the house”: The feminine and professional identity of daycare center directors in Israel. Researchers@Early Childhood, 14, 1–30. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365842278_Before_you_invite_guests_you_need_to_clean_up_your_house (accessed on 22 June 2024). (In Hebrew).

- Achituv, S., & Hertzog, E. (2022). “Sitting around a round table, not a rectangular one”: Attitudes of early childhood daycare directors towards the “Community Building” project. Social Issues in Israel, 31(2), 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adi-Yaffe, A. (2022). Infrastructure document for policy on reforms and changes in education systems for ages birth to six. Office of the Chief Scientist, Ministry of Education. Available online: https://meyda.education.gov.il/files/LishcatMadaan/SkirotSifrut/early-childhood-policy.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Ahmad, J., Saffardin, S. F., & Teoh, K. B. (2020). How does job demands and job resources affect work engagement towards burnout? The case of Penang preschool. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 24(2), 1888–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alase, A. (2017). The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): A guide to a good qualitative research approach. Australian International Academic Centre. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbiv-Elyashiv, R., & Zimmerman, V. (2015). Who is the teacher who drops out? Demographic, occupational and institutional characteristics of those who drop out of teaching. Dapim, 59, 175–206. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Awwad-Tabry, S., Levkovich, I., Pressley, T., & Shinan-Altman, S. (2023). Arab teachers’ well-being upon school reopening during COVID-19: Applying the Job Demands–Resources Model. Education Sciences, 13(4), 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M. C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(2), 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A. B., & Mostert, K. (2024). Study demands–resources theory: Understanding student well-being in higher education. Educational Psychology Review, 36(3), 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenthien, J., Oppermann, E., Anders, Y., & Steffensky, M. (2020). Preschool teachers’ learning opportunities in their initial teacher education and in-service professional development–do they have an influence on preschool teachers’ science-specific professional knowledge and motivation? International Journal of Science Education, 42(5), 744–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, N., & Gutman, Y. (2020). Quality of education-care in settings for children under the age of 3: Selected findings and recommendations for daycare centers and family nurseries in Israel [From the OECD Talis international study on early childhood education and care, 2018] [PowerPoint presentation]. JDC Israel, Ashalim. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bierman, K. L., Heinrichs, B. S., Welsh, J. A., & Nix, R. L. (2020). Reducing adolescent psychopathology in socioeconomically disadvantaged children with a preschool intervention: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(4), 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnet, G. (2025). Preschool children educational report—Governmental infrastructure for preschool children. Oranim College of Education: The Institute for Early Childhood Education. Available online: https://www.oranim.ac.il/sites/heb/content/kidum/docs/%D7%93%D7%95%D7%97-%D7%94%D7%97%D7%99%D7%A0%D7%95%D7%9A-2025.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Blöchliger, O. R., & Bauer, G. F. (2024). Why do childcare teachers leave? Why do they stay?—Pre-Pandemic evidence. Early Education and Development, 35(5), 879–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownstein-Berkowitz, H. (2023). The contribution of resilience and empowerment resources to reducing burnout among young mothers: The mediating role of balance in the career-family conflict. Psycho-Actuality, 90, 29–38. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Cadima, J., Ferreira, T., Guedes, C., Alves, D., Grande, C., Leal, T., Piedade, F., Lemos, A., Agathokleous, A., Charalambous, V., Vrasidas, C., Michael, D., Ciucurel, M., Chirlesan, G., Marinescu, B., Duminica, D., Vatou, A., Tsitiridou-Evangelou, M., Zachopoulou, E., & Grammatikopoulos, V. (2025). Does support for professional development in early childhood and care settings matter? A study in four countries. Early Childhood Education Journal, 53, 1181–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council for Higher Education. (2017). Report of the committee for the evaluation of the quality of curriculum for training early childhood educators in colleges of education: A cross-sectional report. Council for Higher Education, Israel. Available online: https://bit.ly/4n7seYf (accessed on 20 May 2024). (In Hebrew)

- De Los Santos, R., Borchardt PsyD, J. N., Yousey, B., Dickson, S., Aloise, S., Butler, M., & Banker Ed D, D. (2023). A narrative review of preschool teacher burnout. Modern Psychological Studies, 29(2), 1–23. Available online: https://scholar.utc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1603&context=mps (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, S. A., Mortari, L., & Silva, R. (2021). Preschool teachers’ emotion socialization and child social-emotional behavior in two countries. Early Education and Development, 33(5), 806–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egert, F., Dederer, V., & Fukkink, R. G. (2020). The impact of in-service professional development on the quality of teacher-child interactions in early education and care: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 29, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, F. (2013). Knowledge and discourse: The evolution of research on teacher thinking. In Insights into teachers’ thinking and practice (pp. 15–41). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Emolina, I. (2011). Burnout among the childcare educators in the private childcare sector in the area of north Co. Kildare and Co. Dublin [Bachelor’s Thesis, DBS School of Arts]. Available online: https://esource.dbs.ie/bitstream/10788/291/3/ba_emolina_i_2011.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Fináncz, J., Nyitrai, Á., Podráczky, J., & Csima, M. (2020). Connections between professional well-being and mental health of early childhood educators. International Journal of Instruction, 13(4), 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner-Neblett, N., Henk, J. K., Vallotton, C. D., Rucker, L., & Chazan-Cohen, R. (2021). The what, how, and who, of early childhood professional development (PD): Differential associations of PD and self-reported beliefs and practices. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 42(1), 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gat, L., & Dayan, Y. (2021). Cultural adaptation of the “Learning to Live Together” intervention program for kindergarten teachers in Arab society in Israel. Mifgash—Educational-Social Work, 53, 65–88. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, E. E., Avari, P., Hatton-Bowers, H., & Schachter, R. E. (2025). ‘The kids. that’s my number one motivator’: Understanding teachers’ motivators and challenges to working in early childhood education. Early Childhood Education Journal, 53, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasaisi, R. (2014). The status and conditions of employment of childcare workers in daycare centers and family nurseries. Knesset Research and Information Center. Available online: https://fs.knesset.gov.il/globaldocs/MMM/35596b58-e9f7-e411-80c8-00155d010977/2_35596b58-e9f7-e411-80c8-00155d010977_11_7446.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Heilala, C., Kalland, M., Lundkvist, M., Forsius, M., Vincze, L., & Santavirta, N. (2021). Work demands and work resources: Testing a model of factors predicting turnover intentions in early childhood education. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(3), 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumani, N. B., & Malik, S. (2017). Promoting teachers’ leadership through autonomy and accountability. In I. H. Amzate, & N. P. Valdes (Eds.), Teacher empowerment toward professional development and practices: Perspectives across Borders (pp. 21–41). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S. N. (2014). Qualitative research method: Grounded theory. International Journal of Business and Management, 9(11), 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laor, N. (2016). Toddlers at risk in Israel: The relationship between the quality of care-education in day care centers and experiences, and language, emotional, and social development [Doctoral Thesis, Hebrew University]. [Google Scholar]

- Levkovich, A., & Elyosef, Z. (2020). Education students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The connection between childhood memories and their choice in education and teaching. Dvarim, 13, 85–107. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A. J., Liem, G. A. D., Collie, R. J., Malmberg, L. E., & Mainhard, T. (2025). School-level academic and cultural demands and resources: Their role in immigrant students’ motivation and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matattov Sekeles, H., Zadok, I., Zur, H., & Huss, E. (2024). ‘I’m no longer myself anymore’: Burnout and coping of educators-caregivers in day-care centers in Israel. Early Child Development and Care, 194, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondi, C. F., Magro, S. W., Rihal, T. K., & Carlson, E. A. (2024). Burnout and perceptions of child behavior among childcare professionals. Early Childhood Education Journal, 52, 1803–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J., Rogers, M., & McNamara, C. (2023). Early childhood educator’s burnout: A systematic review of the determinants and effectiveness of interventions. Issues in Educational Research, 33(1), 173–206. [Google Scholar]

- Obee, A. F., Hart, K. C., & Fabiano, G. A. (2023). Professional Development Targeting classroom management and behavioral support skills in early childhood settings: A Systematic review. School Mental Health, 15(2), 339–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., Downer, J. T., Burchinal, M., Williford, A., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Howes, C., La Paro, K., & Scott-Little, C. (2022). Early childhood professional development: Coaching and coursework effects on indicators of children’s school readiness. Early Education and Development, 33(4), 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R. C., Whittaker, J. E., Vitiello, V., Ruzek, E., Ansari, A., Hofkens, T., & DeCoster, J. (2020). Children’s school readiness skills across the pre-K year: Associations with teacher-student interactions, teacher practices, and exposure to academic content. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 66, 101084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, M. (2023). Early childhood reform in the education system: An overview. Research and Information Center. Available online: https://fs.knesset.gov.il/globaldocs/MMM/5f984b4a-a37f-ed11-8155-005056aa4246/2_5f984b4a-a37f-ed11-8155-005056aa4246_11_19909.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Ragadu, S. C., & Rothmann, S. (2025). Job Demands-Resources Profiles and Work Capabilities: Effects on Early Childhood Development Practitioners’ Functioning. Early Childhood Education Journal, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recchia, S. L., & Fincham, E. N. (2019). The significance of infant/toddler care and education. In C. P. Brown, M. B. McMullen, & N. File (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of early childhood care and education (pp. 197–218). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev, M., & Gidalevich, S. (2024). Social emotional learning in teacher education: Biographical narrative as a method for professional development. Education Sciences, 14(8), 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavit, Y., Gal, J., & Shay, D. (2018). Emerging early childhood inequality: On the relationship between poverty, sensory stimulation, child development, and achievement. Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, S., & Blank, C. (2023, December). Early childhood education and care in Israel: An overview. State of the Nation Report. Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel. Available online: https://www.taubcenter.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Early-Childhood-2023-HEB-2.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024). (In Hebrew)

- Siraj, I., Kingston, D., & Neilsen-Hewett, C. (2019). The role of professional development in improving quality and supporting child outcomes in early education and care. Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education, 13(2), 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Comptroller. (2022). The care and education of toddlers in day care centers and family nurseries: Systemic issues. Annual Report: Office of the State Comptroller and Ombudsman. Available online: https://www.mevaker.gov.il/sites/DigitalLibrary/Documents/2022/2022.5/2022.5-103-Meonot-Yom.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Stillman, J. (2011). Teacher learning in an era of high-stakes accountability: Productive tension and critical professional practice. Teachers College Record, 113(1), 133–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, E., Cohen, D., Mizrachi, C. D., & Sagi-Schwartz, A. (2024). Early childcare setting in Israel: Structural quality, caregiver sensitivity, and children’s behavior. Early Child Development and Care, 194, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (2015). Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Studny, M., & Oplatka, Y. (2022). Leading at eye level: Ways to motivate employees in kindergartens in Israel. Studies in Education Administration and Organization, 37, 169–198. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/11mbF-5_KFeL4OFNoxYmPNK9mh3MEc0TO/view (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Timor, T. (2017). The journey of novice teachers: Perceptions of interns from a teacher training program for academics. Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (1947–2900), 9(2), 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Trachtenberg, M., Zer-Aviv, H., Leizer, R., & Uziel, E. (2019). Turning the pyramid upside down: Vision and policy for early childhood in Israel. Shmuel Neeman National Policy Research Institute. Available online: https://www.neaman.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Turning-the-Pyramid-Upside-Down_20190314111450.251.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Tzuriel, D., Cohen, S., Feuerstein, R., Devisheim, H., Zaguri-Vittenberg, S., Goldenberg, R., Yosef, L., & Cagan, A. (2021). Evaluation of the Feuerstein Instrumental Enrichment (FIE) program among Israeli-Arab students. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 11(1), 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaknin, D. (2020). Early childhood education and care in Israel compared to the OECD: Enrollment rates, employment rates of mothers, quality indices, and future achievement. Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel. Available online: https://www.taubcenter.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/earlychildhood2020en.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Vaknin, D. (Ed.). (2021). Early childhood in Israel: Findings from selected studies. Taub Center Initiative for the Study of Early Childhood Development and Inequality. Available online: https://www.taubcenter.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/HE-ECEC-booklet-ONLINE.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2023). (In Hebrew)

- Vitiello, V. E., Nguyen, T., Ruzek, E., Pianta, R. C., & Whittaker, J. V. (2022). Differences between pre-k and kindergarten contexts and achievement across the kindergarten transition. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 80, 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T., & Wise, V. (2012). Critical absence in the field of educational administration: Framing the (missing) discourse of leadership in early childhood settings. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 7(2), n2. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ973803.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Zano, G. (2019). Childcare workers’ perceptions of emotional and social development of infants in daycare centers of the Israel Society for Community Centers. Online. Researchers@Early Childhood, 9, 22–59. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H., Cheng, X., & Ai, Y. (2024). How social-emotional competence of Chinese rural kindergarten teachers affects job burnout: An analysis based on mediating and moderating effects. Early Childhood Education Journal, 53, 539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Students Who Started the Training in 2022–2023 | Number of Students Who Completed the Training | Number of Dropouts | Percentage of Dropouts | Number of Participants in the Study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| College No. 1 | 104 | 87 | 17 | 16% | 6 |

| College No. 2 | 103 | 89 | 14 | 14% | 3 |

| College No. 3 | 59 | 49 | 10 | 17% | 2 |

| College No. 4 | 120 | 90 | 30 | 25% | 4 |

| Mother Tongue | Hebrew (N = 9) | Russian (N = 2) | Arabic (N = 4) | Spanish (N = 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 23–64 | 36–57 | 26–45 | 45 |

| Years of Education | 10–14 | 13–14 | 12–16 | 18 |

| Years of Experience | 0.4–40 | 0.3–19 | 2–5 | 14.5 |

| Number of Training Sessions | 4–20 | 4–12 | 4–5 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lavi, N.; Achituv, S. “It Required Lots of Energy from Me and I Didn’t Feel I Received Much in Return”: Perceptions of Educarers Who Dropped Out of the Ministry of Education’s Training Course Towards Their Dropping Out. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081025

Lavi N, Achituv S. “It Required Lots of Energy from Me and I Didn’t Feel I Received Much in Return”: Perceptions of Educarers Who Dropped Out of the Ministry of Education’s Training Course Towards Their Dropping Out. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081025

Chicago/Turabian StyleLavi, Nurit, and Sigal Achituv. 2025. "“It Required Lots of Energy from Me and I Didn’t Feel I Received Much in Return”: Perceptions of Educarers Who Dropped Out of the Ministry of Education’s Training Course Towards Their Dropping Out" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081025

APA StyleLavi, N., & Achituv, S. (2025). “It Required Lots of Energy from Me and I Didn’t Feel I Received Much in Return”: Perceptions of Educarers Who Dropped Out of the Ministry of Education’s Training Course Towards Their Dropping Out. Education Sciences, 15(8), 1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081025