Disconnected in a Connected World: Improving Digital Literacies Instruction to Reconnect with Each Other, Ideas, and Texts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Language Comprehension and Digital Literacies: An Evolution

3. Instructional Context

3.1. New Literacies

3.2. Content Area Reading and Language Arts in Middle and Secondary Schools

3.3. Examining Content, Culture, and Current Events Through Children’s and Young Adult Literature

4. Shared Instructional Methods

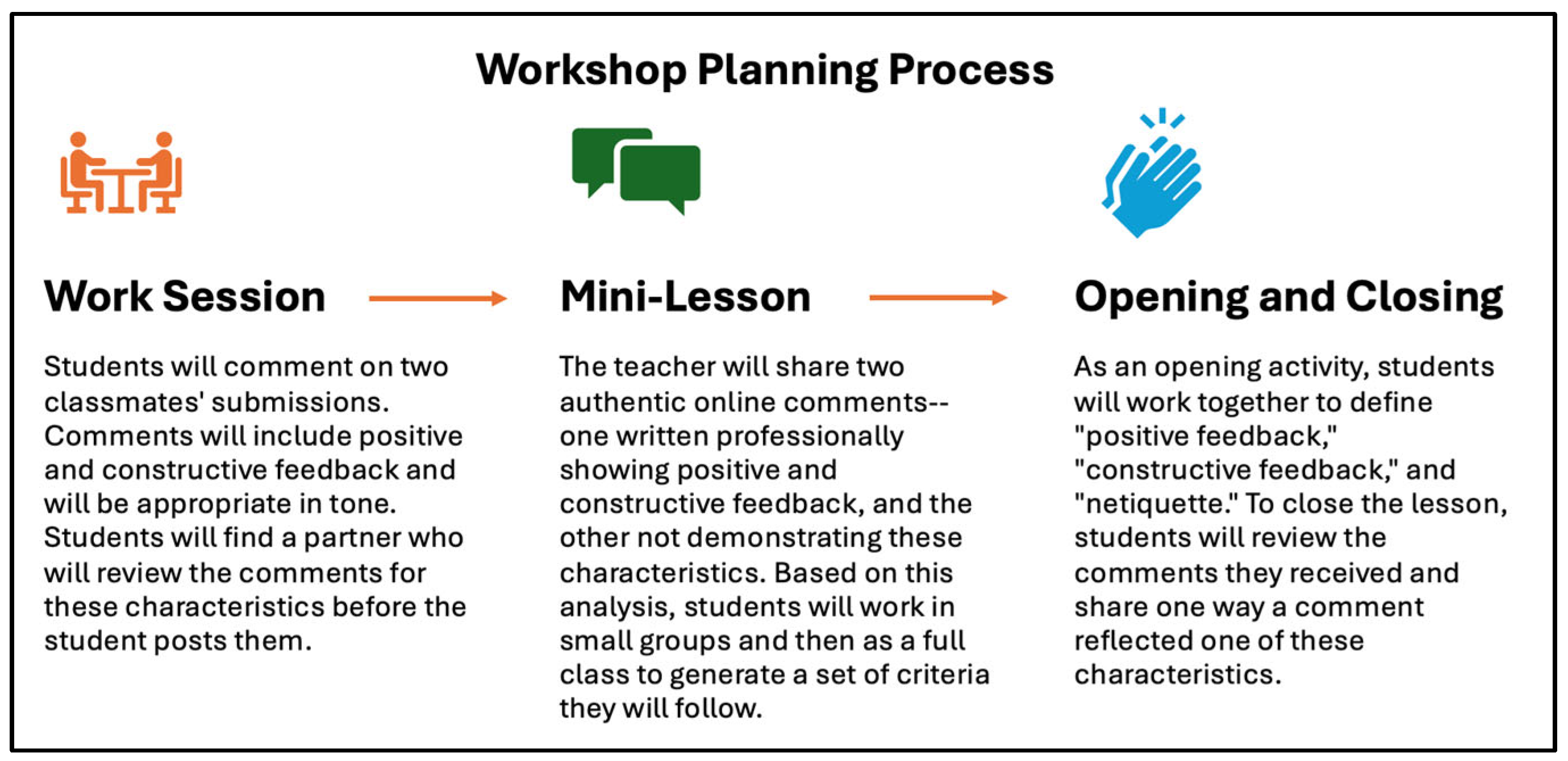

4.1. Workshop Model

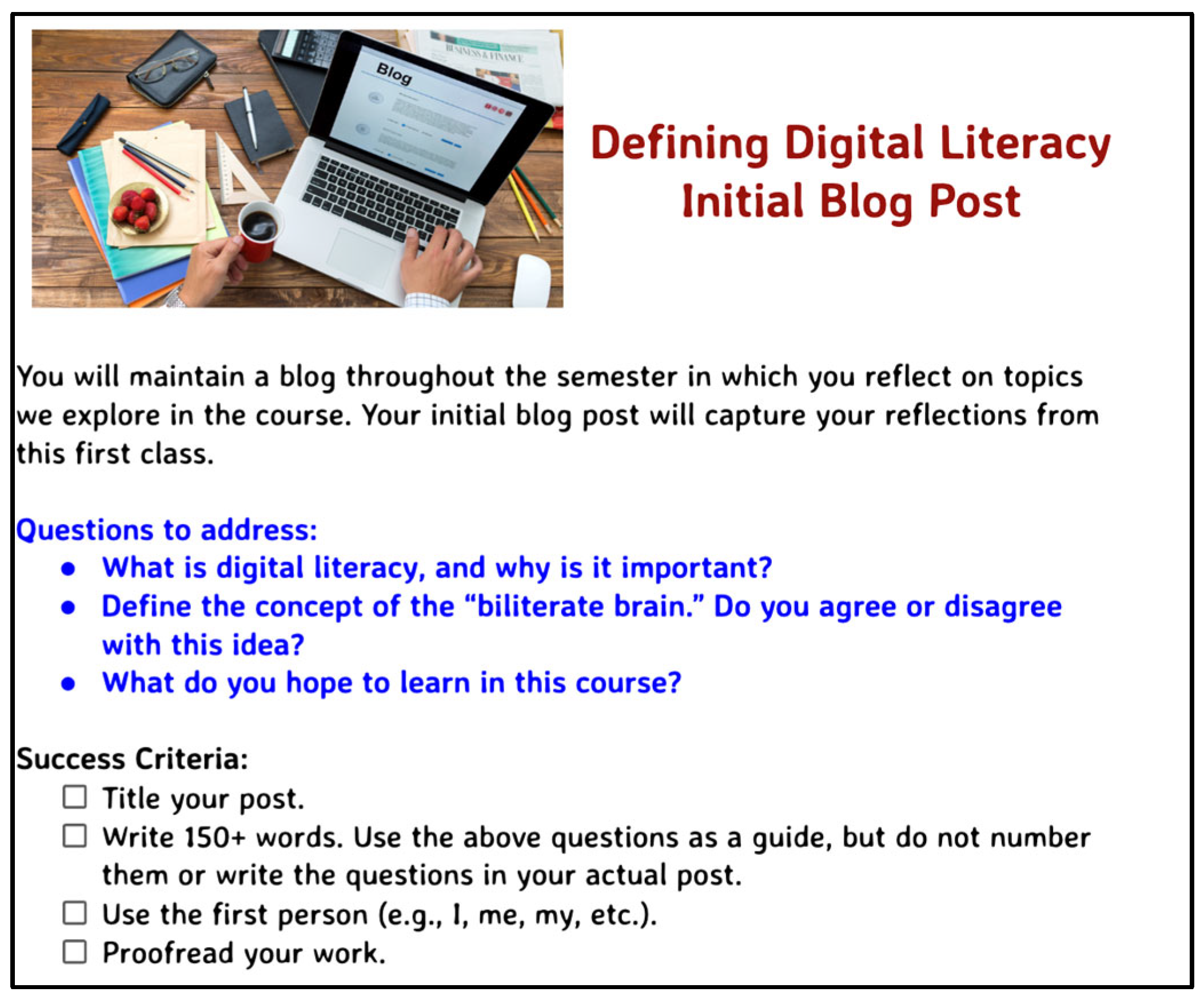

4.2. Balance of Traditional and Technology Fluency

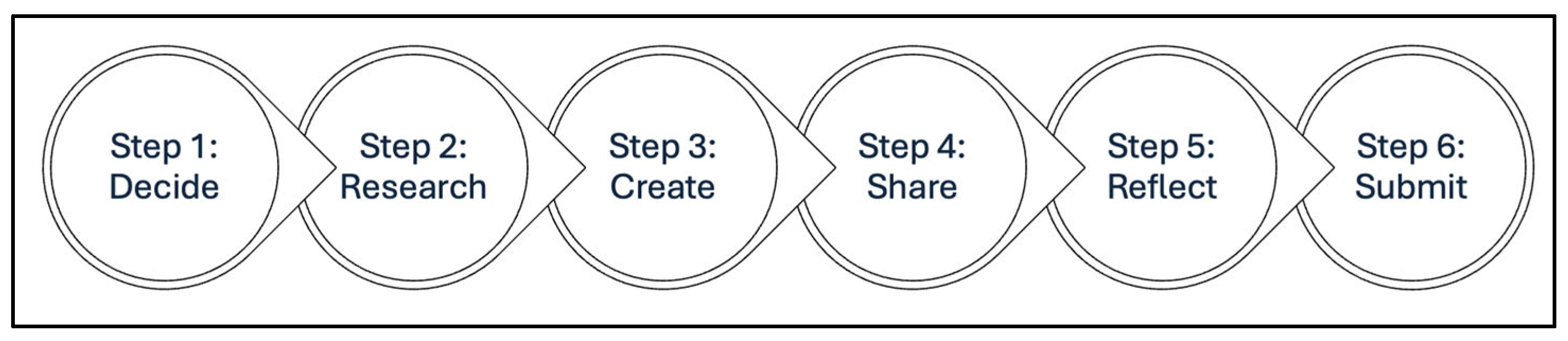

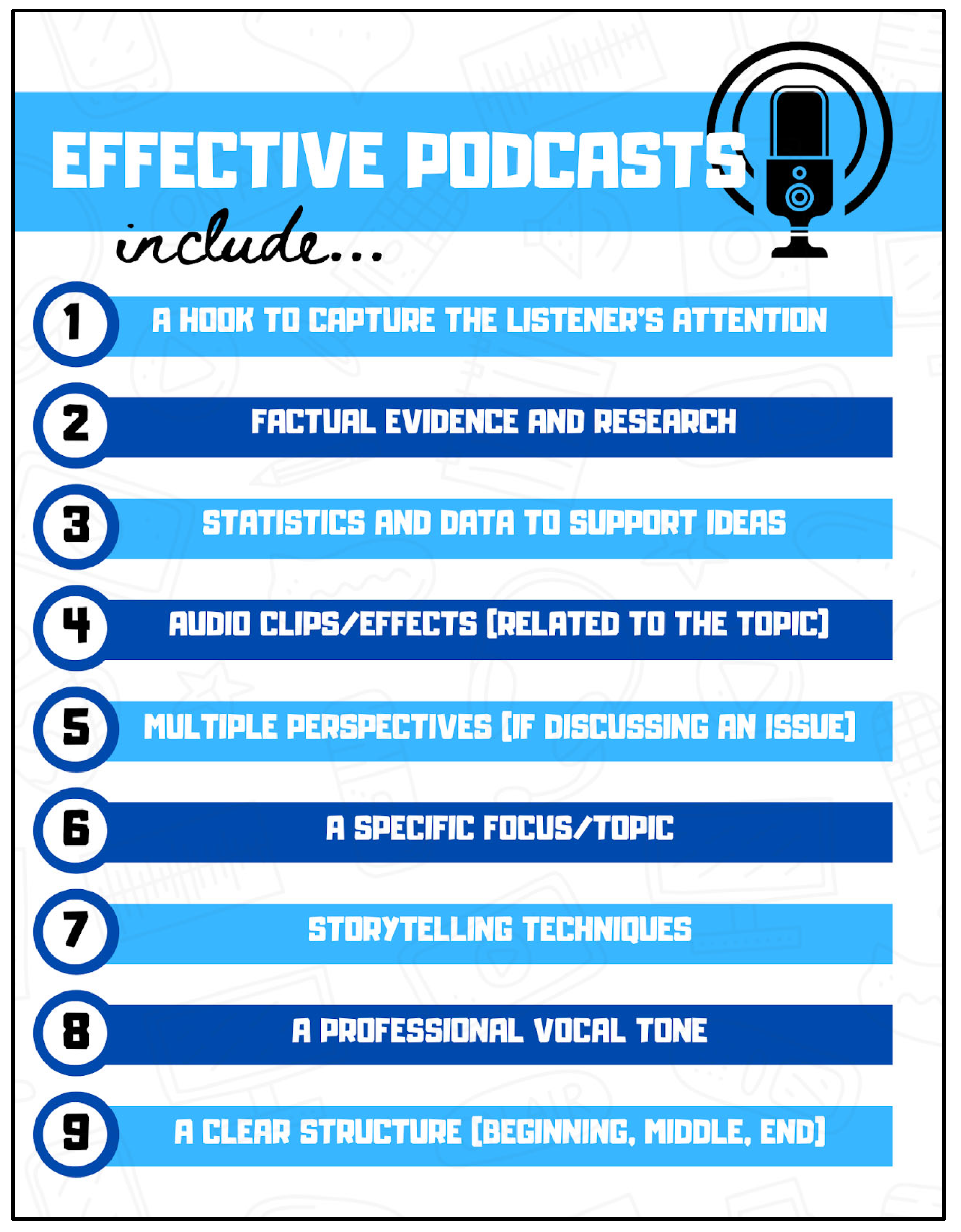

4.3. Authentic and Multimodal Projects

4.4. Source Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adjin-Tettey, T. D. (2020). Can ‘digital natives’ be ‘strangers’ to digital technologies? An analytical reflection. Inkanyiso: Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 12(1), 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, M. (2020). An exploratory study of online equity: Differential levels of technological access and technological efficacy among underserved and underrepresented student populations in higher education. Interdisciplinary Journal of e-Skills and Lifelong Learning, 16, 93–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, N. (2010). The shallows: How the internet is changing the way we think, read, and remember. Atlantic Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Castek, J., & Gwinn, C. B. (2020). Literacy and leadership in the digital age. In A. S. Dagen, & R. M. Bean (Eds.), Best practices of literacy leaders (2nd ed., pp. 258–279). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield, M. (2019, May 12). Introducing SIFT, a four moves acronym. Hapgood. Available online: https://hapgood.us/2019/05/12/sift-and-a-check-please-preview/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Chen, S. Y. (2023). Generative AI, learning and new literacies. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange (JETDE), 16(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiro, J. (2011). Predicting reading comprehension on the Internet: Contributions of offline reading skills, online reading skills, and prior knowledge. Journal of Literacy Research, 43, 352–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T., & Frey, T. K. (2021). Teaching digital natives where they live: Generation Z and online learning. In R. Robinson (Ed.), Communicating, engaging, and educating Generation Z: Theoretical and practical implications for instructional spaces (pp. 71–84). Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, D., & Cambourne, B. (2018). Teaching decisions that bring the conditions of learning to life. Available online: https://foundationforlearningandliteracy.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Teaching-decisions-that-bring-the-conditions-of-learning-to-life-1.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Delgado, P., Vargas, C., Ackerman, R., & Salmerón, L. (2018). Don’t throw away your printed books: A meta-analysis on the effects of reading media on reading comprehension. Educational Research Review, 25, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, A. (1992). Reading from paper versus screens: A critical review of the empirical literature. Ergonomics, 35(10), 1297–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, M., & Haselgrove, M. (2000). The effects of reading speed and reading patterns on the understanding of text read from screen. Journal of Research in Reading, 23(2), 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakle, A. J. (2009). Museum literacies and adolescents using multiple forms of texts “on their own”. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53(3), 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Lapp, D. (2012). Teaching students to read like detectives: Comprehending, analyzing, and discussing text. Solution Tree Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, K. (2011). Write like this: Teaching real-world writing through modeling and mentor texts. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, J. P. (1999). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gilster, P. (1997). Digital literacy. Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ignite Talks. About—Ignite talks. n.d. Available online: https://www.ignitetalks.io/about (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- International Literacy Association. Literacy glossary. n.d. Available online: https://www.literacyworldwide.org/get-resources/literacy-glossary (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- International Reading Association. (2009). New literacies and 21st-century technologies: A position statement of the International Reading Association [PDF]. Available online: https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/where-we-stand/new-literacies-21st-century-position-statement.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Jaeger, P. T., & Taylor, N. G. (2021). Arsenals of lifelong Information literacy: Educating users to navigate political and current events information in a world of ever-evolving misinformation. The Library Quarterly, 91(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucaser, A. M. R., & Acedera, A. P. (2025). Information literacy skills and critical thinking strategies: Key factors of online source credibility evaluation skills. International Journal of All Research Writings, 6(7), 128–137. [Google Scholar]

- Marangell, J. P. (2023). High school social studies teachers’ perceptions and practices using workshop model: An action research study. In N. Nasr-Barakat, & J. Perry (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives through action research across educational disciplines: The K-12 classroom (pp. 87–109). Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, D. S. (2024). Toward culturally digitized pedagogy: Informing theory, research, and practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 59(2), 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, C. V., & VanGronigen, B. A. (2021). The best-laid plans can succeed. Educational Leadership, 78(7), 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Morawski, C., & Sokolowski, J. (2023). The experiences of three teachers using body biographies for multimodal literature study. International Journal for Talent Development and Creativity, 11(1), 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PBL Toolkit. (2021). Project based learning handbook for middle & high school. Buck Institute for Education. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, R. E., & Marangell, J. P. (2020). One story creates another: Using book clubs to promote inquiry in the content areas. Inquiry in Education, 12(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, R. E., & Mercurio, M. L. (2016). Tributes beyond words: Memorializing the triangle shirtwaist factory fire through the intersection of art, history and literacy for pre-service educators. Journal for Learning through the Arts: A Research Journal on Arts Integration in Schools and Communities, 12(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, R. E., & Mercurio, M. L. (2018). Imagination, literacy, and design: Content area curation in the secondary classroom. Teacher Education and Practice, 31(1), 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, T. (2023, July 8). Can we really teach prosody and why would we want to? Shanahan on Literacy. Available online: https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/can-we-really-teach-prosody-and-why-would-we-want-to (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Shanahan, T. (2024, November 9). Is comprehension better with digital text? Shanahan on Literacy. Available online: https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/is-comprehension-better-with-digital-text-1 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Shea, V. (1994). Netiquette. Albion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tovani, C. (2011). So what do they really know?: Assessment that informs teaching and learning. Stenhouse Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Vuorikari, R., Kluzer, S., & Punie, Y. (2022). DigComp 2.2: The digital competence framework for citizens—With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes (EUR 31006 EN). Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, J. (2023). Fighting fake news: Teaching students to identify and interrogate information pollution. Corwin. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M. (2018). Reader come home: The reading brain in a digital world. Harper. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marangell, J.; Randall, R. Disconnected in a Connected World: Improving Digital Literacies Instruction to Reconnect with Each Other, Ideas, and Texts. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081026

Marangell J, Randall R. Disconnected in a Connected World: Improving Digital Literacies Instruction to Reconnect with Each Other, Ideas, and Texts. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081026

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarangell, Joseph, and Régine Randall. 2025. "Disconnected in a Connected World: Improving Digital Literacies Instruction to Reconnect with Each Other, Ideas, and Texts" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081026

APA StyleMarangell, J., & Randall, R. (2025). Disconnected in a Connected World: Improving Digital Literacies Instruction to Reconnect with Each Other, Ideas, and Texts. Education Sciences, 15(8), 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081026