1. Introduction

In Melbourne, Australia, where this study is set, during the initial outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022), people endured six separate lockdowns totalling 262 days. During some of these lockdowns, schools and early childhood services and playgrounds were closed. Restrictions were placed on travel (within a five-kilometre radius), curfews were imposed, and time outside of the home premises was restricted, sometimes to only one hour a day. Interim regulations between lockdowns continued to limit movement and social interaction.

The impacts of the lockdowns were varied. For many families, lockdowns resulted in a decrease in physical activity and an increase in screen time over an extended period. Psychological impacts have also been noted among pre-school children, with Vasileva and colleagues [

1] finding that Australian preschool children were worried about getting sick and infecting others, as well as changes to their daily life. COVID-19-related worries appeared to enter family conversations, play, and drawings, and resulted in behavioural changes (including arousal, cautiousness, avoidance, and attachment-seeking behaviour), with emerging research from other countries illustrating the negative impact of COVID-19 confinement on young children’s physical activity and sedentary behaviours (e.g., extra screen time). This includes Spain [

2] and the Republic of Ireland [

3]. Emerging evidence is also showing that babies born during the pandemic have a greater risk of being vulnerable in the domains of fine and gross motor, personal, and social skills [

4]. In addition, parenting experiences have been impacted as well, with Egan et al. [

5] finding that being at home negatively impacted some parents and carers, who reported increases in their child’s tantrums, anxiety, clinginess, boredom, and under-stimulation.

The spread of COVID-19 among vulnerable populations, including the elderly and those with underlying health conditions, also presented significant challenges. Not only were the elderly, such as grandparents, at higher risk of illness or complications from the virus, but they may also be responsible for caring for others, such as grandchildren [

6]. COVID-19 social distancing and lockdowns highlighted the substantial contributions grandparents make in providing intergenerational support such as childcare for families. The global crisis and the widespread “stay-at-home” government response foregrounded the unpaid care duties of grandparents as families were forced to isolate, early childhood centres shut, and parents worked from home. These conditions affected children’s play with their families and the benefits associated with play in the development of children and older adults.

In this paper, we explore intergenerational play through Rogoff’s [

7] social learning theory focusing on what grandparents as play partners have to offer the young child. We examine intergenerational play episodes through Rogoff’s intertwined and interdependent “personal”, “interpersonal”, and “community” planes. The larger study this paper emerges from was set against the backdrop of the COVID-19 lockdown periods when face-to-face contact was intermittently available under limited circumstances.

Intergenerational family studies are diverse and can consist of participants spanning two (or more) generations with data generated from across generations simultaneously. For example, parents and their children [

8] or children and their grandparents [

9,

10]. For this paper, the notion of intergenerational family practices will be employed to represent two family groups, each spanning three generations.

The impacts of COVID-19 provide an important context for the following discussion. When widespread “stay-at-home” government responses compelled the shutdown of early childhood centres, the relocation of many parents and carers to work from home, the requirement of families to isolate, and the unpaid care duties of grandparents were affected. As a result, the restrictions affected children’s play and the associated benefits for children and older adults.

These unusual conditions enabled the authors to shed new light on the under-researched intersections of intergenerational play. Despite the acknowledged significance of play for both older adults and young children, the intersections of different generations in play have been relatively under-researched, with limited studies exploring the importance of intergenerational play, particularly in the context of play between grandparents and grandchildren [

11]. We build on Rogoff’s theory to explore how learning is shaped by interactions, experiences, and understandings arising from the play between grandparents and young children.

Research has clearly established the role of play in children’s healthy growth and development [

12,

13]. Although defining play can be challenging [

14], researchers agree that play encompasses a combination of characteristics, including being symbolic, meaningful, active, pleasurable, voluntary, intrinsically motivated, rule governed, and having episodic features [

14,

15]. Eberle [

16], for example, assigns five basic qualities to play: “purposeless, voluntary, outside of the ordinary, fun and focused by rules” (p. 215). In addition, play has numerous benefits, including increased physical fitness [

17] and cognitive development [

18], providing the opportunity to learn new skills and adapt them to new situations.

According to Sutton-Smith [

19], play continues to be important throughout life. For older adults, play provides the opportunity for positive behaviours and to develop relationships [

20], and for some grandparents, it can be a meaningful source of leisure [

21]. Other research has identified that intergenerational play offers several benefits, including reducing the stigma that older adults face when engaging in play that is sometimes viewed as childish [

22], as well as providing more leisurely time spent with grandchildren, where the grandparent does not take on the primary caregiver role [

23].

1.1. Grandparents’ and Children’s Play

With grandparents making up to 20 percent of the population globally, the amount of time spent grandparenting is also extending due to increased life expectancy [

24]. Concurrently, assumptions about family structures and the notions of “home” are often oversimplified [

25] and sometimes fail to acknowledge the complexity and significance of intergenerational care [

26]. As grandparenting roles have traditionally been strongly shaped by gender, it is often assumed that grandmothers take on the main role in childcare for young children, and as a result, more encompassing representations of grandparents have been largely absent in the literature [

27].

Grandparents take on diverse roles in their grandchildren’s lives depending on family’s and children’s needs. A study in the United States found that for preschool children, grandparents not only provide important childcare, but importantly at times engage in a range of play activities as playmates or friends during mealtimes, converse with their grandchildren and engage in social-media activities with their grandchildren [

28]. Research has shown that through their interventions, grandparents have a vital role in the affective lives of young children through play across place and time, through activity and dialogue, and through intercultural and multimedia practices [

29].

Intergenerational family practices can both afford and constrain young children’s play. Agate and colleagues’ [

30] study of the experience of grandchildren and grandparents involved in intergenerational play through a visual and text analysis, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, shows how both groups enjoyed and were motivated to engage in play, negotiating constraints during play, and receiving various benefits from playing with each other.

Story reading, for example, can be a pleasurable play-type activity for grandparents to engage in with young children. Gregory et al. [

31], for example, investigated the interlingual and intercultural exchanges of a family in East London during story reading time. The focus of the study was on how a grandmother of Bengali background infused traditional heritage patterns of story and rhyme reading practices when reading with her six-year-old grandchild. The child occupied multiple worlds during the story reading episodes, which reflected the reading styles of his cultural heritage. A complex blending of home and school practices occurred which involved “different texts, languages, scripts and illustrations alongside the fusion of western and traditional Bengali teaching styles …” (p. 21).

Inter- and multigenerational research spanning three or more generations is even more complex in its conceptualisations of grandparenting and intergenerational play. Monk’s [

32] multigenerational Australian research study, for example, highlights “the dialectical complexity of relations, transitions, and transformations within intergenerational families” (p. 183). In Monk’s exploration of intergenerational continuity in, and through, everyday family practices, values and beliefs associated with these practices involve meaningful artefacts, locations for family visits such as the beach and park, knowledge of local environments, food preparation practices and routines of everyday life. Family togetherness is developed through shared experiences of older generations sharing their everyday lives with young children.

Across the research literature, we can see the diverse ways that grandparents act as play partners in young children’s lives depending on the familial and community context. While this study also focuses on the everyday interactions of grandparents and young children, what differs from the previous research is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the nature and shape of intergenerational relationships and the possibilities of play.

1.2. Rogoff: A Context for Viewing Intergenerational Play

Barbara Rogoff provides a way to examine the systematic nature of human development through social learning theory. Our research expands Rogoff’s theory, which provides a context for viewing children’s development, as a lens for exploring the behaviours, understandings, and approaches taken by grandparents in their grandchildren’s play. Specifically, we examine how learning is shaped by interactions, experiences, and understandings derived from grandparents and young children in social and cultural contexts.

Rogoff’s [

33] main premise is that “[the] individual cannot be studied in isolation from the social, and that the individual, interpersonal and cultural process are not independent entities” (p. 687). From this viewpoint we reflect on the interactions and collective engagement of the grandparents and children. Rogoff suggests that learning and development takes place across three “planes” which are intertwined and interdependent—the “personal”, “interpersonal”, and “community” planes. The personal plane centres on how the child transforms their understanding and responsibility of their actions through participation in activities. This process involves acquiring knowledge and skills that can shape future practices. As the child and grandparents engage in group activities, they build new understandings and can feel a sense of belonging. The interpersonal plane analyses the everyday practice and happenings that the child engages in with others focusing on the face-to-face and the more distal aspects of other’s activities [

33]. These interactions can involve both active and deliberate engagement as well as incidental learning; for example, from observing comments and actions. This plane is about the child feeling included and valued by others. The community plane acknowledges that the child will build understanding by interacting with others and focuses on how the child, “engages in culturally organised activity in which the apprentice [child] becomes a more responsible participant” (p. 143). The child will observe and make meaning from their interactions with others—in this case grandparents—developing an understanding of the expected cultural norms [

34].

Through the lens of the three planes, this research explores the child’s interactions with grandparents as the significant “expert” other. We are interested in understanding the dynamics and impact of intergenerational play, during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, on young children’s learning. Using two vignettes, we examine the play practices of grandparents with their grandchildren.

2. Methods

This study adds to the emerging literature on intergenerational everyday practices of grandparents and young children, with data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021–22 in Melbourne and Sydney, the two largest capital cities in Australia. Melbourne is the research team’s location and the location of five of the six families who participated in this research. The family who lives in Sydney is related to the lead researcher and has been involved in previous iterations of this research [

35,

36].

This project builds on a larger qualitative study involving six family groups. Families were known to Author One and direct person-to-person contact was made with the six family groups regarding their participation in the research. The families were chosen as they agreed to family group interviews and the sharing of family photographs and videoclips of intergenerational interactions with the researchers. Ethics approval was obtained from a University Human Ethics Committee to conduct this study [Project ID: 21968] including use of visual materials which identify the participants in this paper, including minors. Child assent was given where applicable and by the six-year-old participant in this paper.

We employed a vignette-based approach for this paper. Quigley et al. [

37] depict a vignette as a concise description of a person, object, or situation that encapsulates essential characteristics. For this paper, we draw on two vignettes to show how grandparents across the COVID-19 lockdown periods were significant figures in creating play opportunities for their grandchildren. The vignettes allow us to explore intergenerational play practices, providing valuable insights into how young children from two families interact with their grandparents within familial contexts. Family one consisted of Louis (six years of age), his mother Ange, and his maternal grandparents Marg and Pete. Family two’s vignette is made up of Nina (two months old) and her maternal grandmother Rina.

Table 1 represents the two family groups involved in this paper.

The study was guided by the following research questions: (i) how can intergenerational play practices integrate linguistic and cultural experiences in young children’s lives? and (ii) in what ways do intergenerational play practices provide a space and time for social interaction and learning for young children?

In this paper, two vignettes are developed using a multimethodological approach to data generation. The intent was to capture the multifaceted, relational, and dynamic everyday life of families with young children, with the research methods drawing on Monk’s [

32] early childhood multigenerational Australian study. Data collected for this paper (see

Table 2 and

Table 3) included video- and/or audio-recorded (face-to-face/Zoom/phone) interviews, with cultural artefacts, photographs, and family videoclips acting as prompts. In addition, the research team visited the family homes and filmed intergenerational play activities with young children when COVID-19 regulations allowed.

Textual data combine with visual data in this intergenerational study, with the visual data enhancing and providing evidence for the textual data. Spencer [

38] contends that “there is something indefinable about the visual, grounding it in material reality. It is an immediate and authentic form which verbal accounts are unable to fully encompass” (p. 32); “images and video open up complex, reflexive and multifaceted ways of exploring social realities” (p. 35). The interview data, transcription of the videos, and film footage combine to provide a rich arena for the exploration of the relations and creation of play affordances during grandparent–grandchild interactions across the COVID-19 lockdowns.

The interview and visual data were sifted and sorted for examples which represented grandparents creating opportunities for children’s play and learning during the COVID-19 period. As with Monk’s study, data analysis “was an iterative process; it does not start and stop in a particular linear sequence. Analysis weaves together the sequences involved in image production, sorting and coding of images, as well as historical, contextual and cultural knowledges of artefacts and social situations” (p. 85) [

39].

We engaged with Microsoft Co-pilot (Artificial Intelligence) to check the weaving together of sequences in the sorting and coding of images and text. Artificial Intelligence was not used for thematizing the data but rather to support the analytic process [

40].

From this methodological vignette approach, rich and meaningful insights are captured of the intergenerational family practices of two families. In the next section, the vignettes are given meaning in dynamic and complex ways, with intergenerational family practices explained and interpreted through Rogoff’s three planes theory.

3. Findings

3.1. Family One: Rogoff’s Personal Plane

Louis was six years old at the time of the research and living with his mother in an apartment in the eastern suburbs of Melbourne. In 2021, he began the foundation year of school, attending a local government primary school which is a French–English bilingual school. Attendance at school was interrupted with long periods of home-schooling, which took place online via Zoom. As his mother Ange was an emergency worker, Louis was granted an exception to attend school part-time during the lockdown periods. Louis has a close relationship with his maternal grandparents, who met him at parks to go for walks and play games such as Australian rules football during the COVID-19 restrictions. In our analysis, we particularly focus on Louis’ interactions with his grandfather.

The transcript below (

Table 4) is from a videoclip of Louis playing footy with his grandfather (Pete) and mother (Ange) in December 2021 at a neighbouring community park that they liked to visit. The clip was captured out of a lockdown period by the research team. Lockdowns were intermittent with restrictions lifted for periods of time. Louis’ grandmother was on the sidelines, closely watching the footy game. The outdoor space in the park allowed for a form of intergenerational play that had been disrupted for significant periods of time. A game such as football supported the recommencement of intergenerational play in a safe, open space.

The videoclip, although captured outside a period of restrictions, represents how the family played during the COVID-19 lockdown times, when play was permitted in public spaces. The space in the park allowed for a minimum of 1.5 m distance between people as mandated by government regulations.

We use this vignette of Louis’ family playing footy to explore Rogoff’s [

33] personal plane, which is concerned with how the child transforms his understanding and responsibility for his play actions through participation in intergenerational play activities. We look at how he acquires knowledge and skills for shaping future practices.

The game of footy, a popular game in Melbourne, Australia, for children of all ages to play and watch, influenced the intergenerational interactions between Louis and his mother and grandparents. Through the game of footy with his mother and grandparents, Louis (re)engaged in shared intergenerational play practices.

Figure 1 shows the family members physically distanced, an ongoing expectation of people as they returned to community activities. Yet, the open space of the park facilitated closer physical engagement than isolation, while the game of footy, which requires distance for players to kick or move the ball to each other, provided “safe” re-engagement in play for Louis and his family.

As the family played footy, they took turns to kick and hand-ball the football. During their play, the grandfather along with the mother are play partners who offered Louis guidance, encouragement, and direction for playing the game. Louis’ grandfather and mother were experienced with playing footy and passed their knowledge about the game onto Louis. The play episode illustrates how the grandfather and mother taught this game of skill and strategy to Louis, giving him time to practice his play in a secure familial environment.

The extract in

Table 4 illustrates how Pete and Ange guide Louis in how to play football. They tell him to “watch the ball” (Pete) and “you’re kicking it too …” (Ange). Louis is directed to practice his footy manoeuvres with Pete suggesting “try that again”. Louis also receives encouragement from Pete, who yells “good catch”. Louis himself, at one stage, critiques his own footy game saying “too small” [a kick]. The grandmother, on this occasion, provided support for the family interaction as a spectator and observer.

Within the confines of the COVID-19 pandemic, the activities and play artefacts (e.g., football) are central to Louis’ play and “safely” moderate relations in the intergenerational play activity. The photo (a still from the videoclip) and transcript capture the real yet play-world of the family [

41]. The grandfather and mother as play partners, and grandmother as onlooker, become part of Louis’ play-world and by so doing, grow their relationship with him. The play episode shows how engaging in intergenerational play practices builds new understandings and solidifies a sense of belonging to family.

3.2. Family 2: Rogoff’s Interpersonal Plane

Sara gave birth to Nina during the first lockdown that took place in Australia from March to April in 2020. After the birth of Nina and during Victoria’s first COVID-19 lockdown, Sara and her husband lived with Sara’s parents at their winery in a regional area of Victoria. Sara has a grandmother, Tina, and a younger sister Danielle, who also gave birth to a baby daughter Maia, about nine months after Nina was born. Both Tina and Danielle live near Rina’s Melbourne home. The extended family are very close and Rina, then Sara and Danielle, made the decision to raise their children bilingually in Italian and English.

Sara talks about living with her parents during the lockdowns:

during last year’s lockdown, when we were up there [living at the winery with Mum and Dad] for the first lockdown. And then, for the second lockdown, we ended up going up there [again]. Nina spent a lot of time with Mum and Dad … being an intergenerational family in a home together. I think that’s something that without the pandemic, we would never have had. And I think that time was so special…

Sara, Nina’s mother, spoke of the extended time she and Nina spent with her parents as an intergenerational family living together in her parent’s home during the pandemic. Sara names this time as “special” as it was unique to the lockdown period, an affordance that she was able to leverage to create an intergenerational experience that would have otherwise not existed as her parents took on a significant role of carers and play partners for Nina during this time.

We use the interpersonal plane to analyse the everyday practice and happenings that the baby engaged in with the grandmother, focusing on the face-to-face and the more distal aspects of the intergenerational play activity. These interactions involve both active and deliberate interactions as well as incidental learning (See

Table 5). This plane is about the baby feeling included and valued by her grandmother.

Rina, the grandmother, embedded ways of enacting a story during her reading practice with her young grandchild, Nina. She found rhythm in her storytelling, just like it is presumed she did when she read the same story to her own children when they were young. The story was read in her home language, Italian, in response to the families’ linguistic and cultural heritage and experiences. For Rina and Nina, the strictures of the lockdowns provided an unexpected intergenerational experience that facilitated the sharing and maintenance of their heritage language and culture through the opportunity to replicate the use of Italian as the home language, which Sara had experienced growing up with her mother Rina. The restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic provided Rina and Sara with an opportunity to harness their heritage language—Italian—as part of their intergenerational practices.

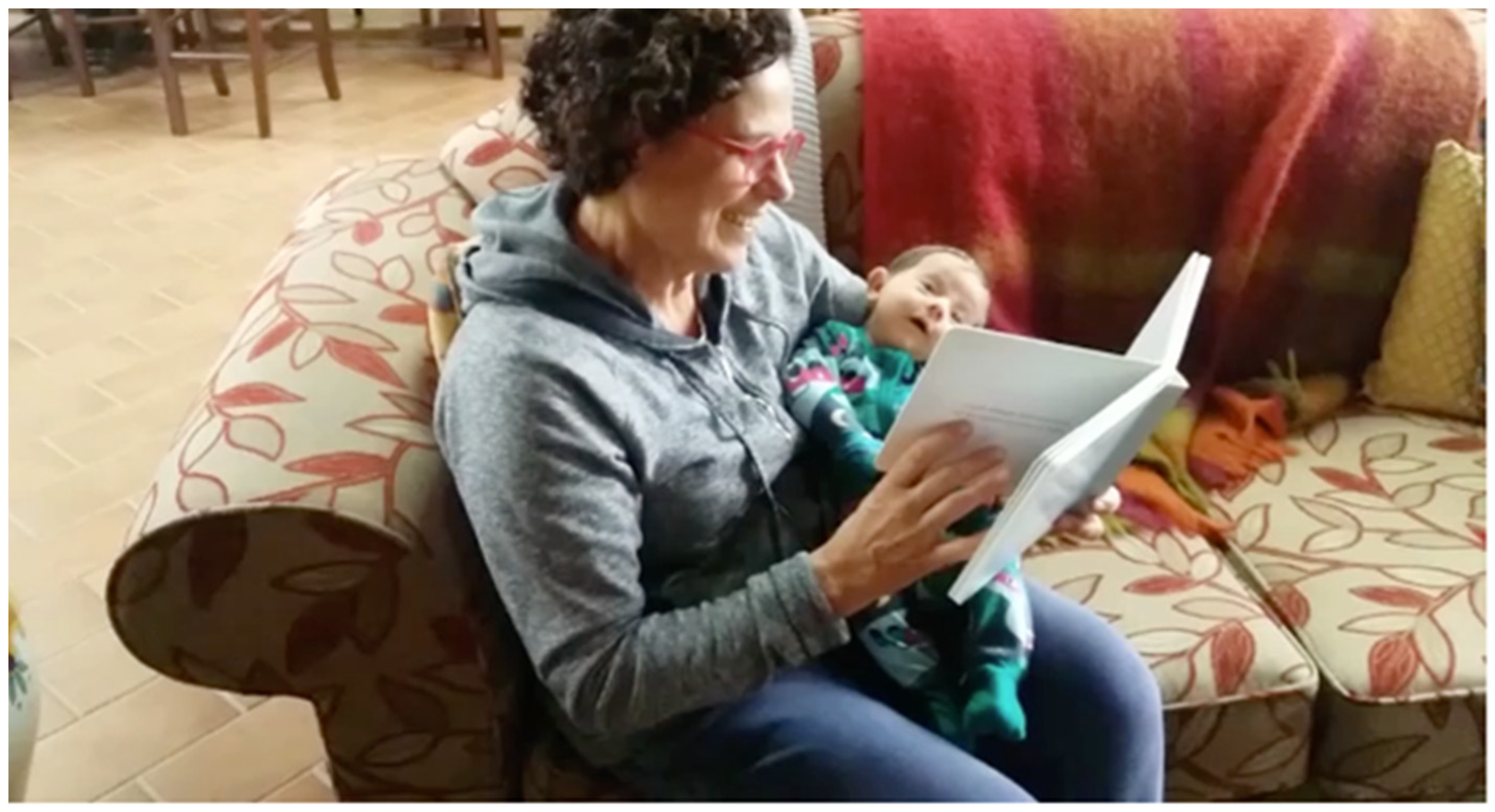

Intergenerational continuity was enabled through everyday familial practices. Values and beliefs associated with child-rearing practices were shared and passed on intergenerationally, such as the speaking of the grandparents’ home language, Italian, in an English-speaking country. Rina read in her home language, Italian, a traditional story which she had read to her own children as babies (see

Figure 2).

Nina reacted with smiles and contentment as Rina interacted with her during the story reading episode. In the excerpt, Rina and the Nina took turns smiling and gesturing as they interacted during the storytelling episode. Nina “takes in things” and developed and learned about becoming a communicative partner as she observed her grandmother reading, enacting the story, and interacting with her. Rina read with expression and a loving tone. She stopped reading to interact with and look at Nina who smiled back at her. The interaction between Rina and Nina is warm and comfortable and one of familiarity. As Rina read, “And I could caress your beautiful little head”, she gently stroked the baby’s head. Rina continued reading, “caressing” and stroking the baby’s face in a caring way. Then she read, “And I could hold your hand in my hand”, while holding the baby’s hand in her own hands. Rina interacted in an affective and physical way with Nina as she read the story.

3.3. Louis and Nina: Rogoff’s Community Plane

According to Rogoff [

42], young children seek to gain a better understanding of their own community contexts to find their place and space within it. Higher-order thinking develops from these social interactions which enable young children to explore ideals, goals, and valued skills in their local contexts. In this paper, Rogoff’s [

33] community plane is used to explain how young children build their understandings of their own community contexts by interacting with their grandparents. By engaging in organised familial activities as the “apprentice”, the young children become more of a “responsible participant” (p. 143). Both Louis and Nina observed their grandparents and by so doing made meaning from their interactions with them. This intergenerational interaction enabled meaning making concerning expected familial and community norms [

34].

The grandparents in these two vignettes were involved in everyday repetitious-type play activities which provided their grandchildren with time to rehearse and recast their play and feel secure in a familial environment. Louis’ grandparents and mother played footy with him, sharing a game that he most probably plays in the school playground with his friends. Footy is likely to be a game that is familiar to Louis and playing with his mother and grandfather provided him with time to practice and refine his kicking and balls skills. While Rina immersed herself in Nina’s play-world through the act of reading a story in her home language, Italian. Grandmother and granddaughter interacted and played together during the story reading episode, growing their relationship and communicative repertoires.

These two vignettes offer a small snapshot in time of how intergenerational play practices afford the growing of relationships between grandparents and their grandchildren. Intergenerational play interactions for these two families offered a way to integrate linguistic and cultural experiences, providing a space and time for social interaction and learning for younger as well as older generations.

Social interactions for young children can foster the development of higher-order thinking by engaging in play and developing skills within their family and local community contexts [

42]. These two vignettes illustrate how young children are helped by grandparents to participate in and learn the languages, behaviours, routines, and cultural practices of their communities [

43]. Engaging with Rogoff’s [

33] three planes theory offers insights into why and how relationships, such as those between grandparents and grandchildren, are enacted and important for young children’s growth and development. In addition, family expectations and approaches toward including grandparents as play partners for their young children come into view.

4. Discussion

Overall, Rogoff’s three planes intersect and influence each other, creating a dynamic interplay [

33] within these two vignettes. Rogoff’s three plane theory provides a valuable lens through which we can understand how young children build their understanding by engaging with their grandparents. The findings show how the two families adapted and continued to foster connections through play, engaging in meaningful intergenerational interactions, even during challenging COVID-19 times.

In the case of Louis, the interactions with his grandparents and mother created a shared context for learning. Expertise about footy was passed down to him through the generations, and skills were developed through the intergenerational interactions. Louis’ experiences during this play episode contributed to shaping his future play practices as he gained insights into social relationships within the family and developed his sense of belonging to the family [

33].

The experiences between Nina and her grandmother Rina exemplify the richness of relationships and language exposure that can occur in such close-knit settings. The extended time together during lockdown periods allowed for bonding, caregiving, and shared play. Rina engaged in various nurturing gestures during her interaction with Nina, fostering emotional connection and amplifying her role as a grandmother, caregiver, and play partner [

32].

Rogoff’s three planes theory provides a valuable lens through which to understand how young children build their understandings and higher-order thinking [

43] by engaging with significant family members as play partners. Observing grandparents allowed them to make meaning from interactions, shaping their understanding of familial and community norms [

34,

42]. The grandparents immersed themselves in the young children’s play, strengthening their relationship and communication [

32]. The shared play experiences provided a secure and safe familial environment. Integrating linguistic and cultural aspects enriched the interactions and offered valuable learning opportunities for all generations [

30]. Play transcended generations creating meaningful connections and nurturing understanding.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This paper helps to build an understanding of the importance of play within intergenerational experiences. The two vignettes in this paper can be understood both as illustrations of intergenerational experiences of grandparents and their grandchildren, as well as experiences situated within the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to acknowledge the factor of time, especially given the conditions of “lockdowns” during COVID-19 when young children did not have access to peers. The pandemic, for some families, allowed greater opportunities for engagement between grandchildren and grandparents. However, for other families, this intergenerational space was constrained by lockdown rules that did not permit travel, and family get-togethers only occurred through online platforms. The role of play, however, became an important tool for connection of either real-time or virtual interactions for grandparents and their grandchildren.

Intergenerational play practices between grandparents and young children, in these two vignettes, were shown to weave together language and cultural elements into the fabric of young children’s everyday experiences and create a sense of belonging. By engaging with grandparents, young children learned not only through play but also through shared language and cultural traditions. Intergenerational play practices created a valuable space and time for young children to interact socially with grandparents. Within these interactions, they developed a sense of belonging and emotional connectedness. These practices fostered holistic development and learning beyond mere play.

This paper reports on a small-scale qualitative research study and as such presents a discussion of vignettes from two families. The intention is to enhance the understanding of intergenerational family play practices through an in-depth analysis of two vignettes, drawing on Rogoff’s three planes theory [

33]. Hence, the interpretations of the data are limited and cannot be generalised [

42]. Further analysis of the data collected from all six families who participated in the study would further optimize our understanding about grandparents’ roles in young children’s play.

Our understanding of intergenerational play requires revisiting in light of, and beyond, the pandemic. Significant research is needed into the impact of and impact on intergenerational play practices, especially involving grandparents as play partners, how these practices are adapted and evolved during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how they continue to morph across families and communities. We know the importance of play interactions for young children and grandparents from research and, in this study, the importance for linguistic and cultural experiences. However, it is important to also explore how these are developed over continued periods of time, especially given changing contextual and cultural factors. This includes the decline of playtime for some children, exposure to different types of play (especially “risky” play), and the current cost-of-living crisis affecting many countries in the world that may limit time for intergenerational interactions because of increased costs (e.g., travel costs for grandparents to visit grandchildren or grandparents having to continue to work).