Abstract

Despite extensive research on early childhood education (ECE) quality at the preschool level, toddler settings remain comparatively understudied, particularly in Chile and Latin America. Research suggests that quality ECE strengthens child development, while low-quality services can be harmful. ECE quality comprises structural features like ratios and classroom resources, and process features related to interactions within classrooms. This study examines how process and structural quality indicators are related in nurseries serving disadvantaged backgrounds. Data were collected from 51 Chilean urban classrooms serving children aged 12–24 months. Classrooms were evaluated using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) for toddlers, questionnaires, and checklists. Latent Profile Analysis identified process quality patterns, while multinomial regression examined associations with structural quality indicators. The results revealed low-to-moderate process quality across classrooms (M = 4.78 for Emotional and Behavioral Support; M = 2.35 for Engaged Support for Learning), with three distinct quality clusters emerging. Marginally significant differences were found between high- and low-performing clusters regarding classroom space (p = 0.06), number of toys (p = 0.08), and staff educational credentials (p = 0.01–0.07). No significant differences emerged for group sizes or adult-to-child ratios, which are heavily regulated in Chile. These findings underscore the need to strengthen quality assurance mechanisms ensuring all children access quality ECE.

1. Introduction

An extensive body of research has highlighted that higher quality early childhood education (ECE) leads to enhanced children’s learning and development (Barros et al., 2016; Britto et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2017; OECD, 2018). Studies from different scientific fields such as neuroscience, economics, and educational science, alongside children’s rights perspectives, have argued that investing in ECE is beneficial for children and society (UNESCO, 2024). Indeed, ECE may constitute a protective factor for children living in poverty contexts (Hu et al., 2017; UNESCO, 2024). Nevertheless, a growing body of research has also indicated that only quality ECE can lead to desirable child outcomes, and that low-quality services can even generate detrimental effects on children’s lives (OECD, 2018). For these reasons, ECE has globally become an appealing area of public investment and policy development (OECD, 2024; UNESCO, 2024), and service quality has become a prominent topic of research in the ECE field.

1.1. Structural and Process Quality in ECE

Service quality in ECE has been extensively defined by the distinction between structural and process variables (Bichay-Awadalla & Bulotsky-Shearer, 2022; Britto et al., 2011; Castle et al., 2019; Lopez Boo et al., 2019). Structural quality embodies aspects of ECE quality that have been identified as measurable and regulable features of the system (Barros et al., 2016; Bichay-Awadalla & Bulotsky-Shearer, 2022; Thomason & La Paro, 2009). This includes variables such as adult-to-child ratios within classrooms, group sizes, teachers’ qualifications and salaries, and program facilities, among others (Buøen et al., 2021; Slot et al., 2015; Sokolovic et al., 2022; Thomason & La Paro, 2009). Such aspects have been defined as “distal” features of quality (Hu et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2024; Slot et al., 2015), and are usually recognized as preconditions of process quality (Slot et al., 2015). Process quality encompasses the dynamic aspects of the classroom and children’s daily experiences (Bichay-Awadalla & Bulotsky-Shearer, 2022; Slot et al., 2015; Thomason & La Paro, 2009). It includes children’s interactions with teachers, peers, and materials (Barros et al., 2016; Mortensen & Barnett, 2015; Slot et al., 2015; Sokolovic et al., 2022), which are features that have been characterized as proximal aspects of quality (Barros et al., 2016; Le et al., 2015). Due to this proximity, their stronger correlation with children’s learning (Luo et al., 2024; Wysłowska & Slot, 2020) and the complexity of accurately measuring them (Le et al., 2015), the focus on process indicators is arguably conceived as the most important component of quality (Buøen et al., 2021), and constitutes a more sophisticated approach to measuring quality (Barros et al., 2016).

While this scholarship has demonstrated greater proliferation in preschool contexts compared to toddlerhood (Bichay-Awadalla & Bulotsky-Shearer, 2022; Castle et al., 2019), there has been mounting scholarly attention toward measuring process quality during the earliest years. To this end, the toddler version of the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) has emerged as one of the most extensively utilized instruments (La Paro et al., 2012). CLASS Toddler examines pedagogical interactions within classroom environments serving children aged 15 to 36 months. The instrument comprises eight analytical dimensions structured across two domains: Emotional and Behavioral Support and Engaged Support for Learning. Although originally developed and predominantly implemented across Global North contexts (Castle et al., 2019; La Paro et al., 2014; Romo-Escudero et al., 2021; Salminen et al., 2021; Slot et al., 2017; Sokolovic et al., 2022), the instrument has demonstrated cross-cultural applicability across diverse contexts, including China (Luo et al., 2024), and Latin America (Gebauer Greve & Narea, 2021; Lopez Boo et al., 2019).

Broadly, studies employing CLASS-T have consistently documented that classrooms demonstrate medium to medium–high quality in the Emotional and Behavioral Support domain, while exhibiting medium–low to low levels in the Engaged Support for Learning domain (Guedes et al., 2020; Salminen et al., 2021; Slot et al., 2015; Sokolovic et al., 2022). These patterns have shown certain consistency across various Global North countries, including studies in Canada (Sokolovic et al., 2022), Portugal (Guedes et al., 2020), Netherlands (Slot et al., 2015), and also Norway (Buøen et al., 2021). Nevertheless, notable cross-national variations have emerged. Salminen et al. (2021) observed that that Finnish classrooms (EBS: 5.58; ESL: 3.35) achieved superior scores in both domains compared to Portuguese classrooms (EBS: 4.53; ESL: 3.17), particularly in Emotional and Behavioral Support. Similarly, a comparative analysis of toddler classrooms in Poland and Netherlands revealed contrasting strengths: Polish settings (EBS: 5.79; ESL: 2.84) excelled in EBS, while Dutch classrooms (EBS: 5.33; ESL: 3.57) demonstrated stronger performance in ESL (Wysłowska & Slot, 2020). Instead, incipient evidence from Ecuador indicates markedly lower performance relative to these established patterns, with classrooms achieving medium–low scores in EBS dimensions and low scores in ESL (Lopez Boo et al., 2019).

Considering that much of countries’ investment in ECE quality is focused on structural quality features—as they are the easiest to regulate (Guedes et al., 2020; Thomason & La Paro, 2009)—it is important to understand the relationship between structural and process quality features. Recently, an array of studies has focused on understanding this correlation in toddler settings (Castle et al., 2019; Lopez Boo et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2024; Wysłowska & Slot, 2020). Several studies have found a moderate correlation between class size and pedagogical interactions (Barros et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2024; Wysłowska & Slot, 2020), though in different directions. For example, some studies have shown a positive correlation between class size and EBS, which can be explained by a greater concern for effectively handling behavior in classrooms with a larger number of children (Luo et al., 2024; Wysłowska & Slot, 2020). Nevertheless, the association between class size and ESL tends to go in the opposite direction (Wysłowska & Slot, 2020). Moreover, there are studies that identify the effects of this variable only from certain thresholds of quality (Hu et al., 2017), and others have not found significant effects (Slot et al., 2015). Regarding child-to-teacher ratios, while some studies found a negative effect on process quality indicators (Lopez Boo et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2024), and others did not find any significant effect (Barros et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2017; Slot et al., 2015).

Evidence regarding the effect of teacher education level on process quality is mixed. While some studies found a moderate effect (Lopez Boo et al., 2019; Slot et al., 2015), others did not show significant correlations (Castle et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2024). Nevertheless, holding an early childhood education specialized degree did show a more consistent positive association with CLASS-T scores (Barros et al., 2016; Castle et al., 2019). In sum, evidence on the association between structural and process quality features is not yet conclusive, and when it is reported, it tends to be weak to moderate (Slot et al., 2015). In this context, some studies have argued that this absence of correlation is due to the existence of strict regulations regarding structural quality features in several countries (Buøen et al., 2021; Lopez Boo et al., 2019; Wysłowska & Slot, 2020). As we will show, Chile is no exception.

1.2. ECE Quality in Chile and Latin America

Chile has an integrated ECE system, in which the educational goals, curriculum, main regulations, and governing institutions are similar for all levels that serve children from 0 to 6 years old (Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia, 2024). According to the national curricular framework, the main goal of ECE in Chile is to promote the comprehensive development and meaningful learning of children, supporting the family in its irreplaceable role as the primary educator (Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia, 2018a). This education-focused goal is consistent across all formal ECE settings and levels, and to date, except for some highly focused alternative programs (Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia, 2024), Chile has no formal early years centers of which the major goal is childcare (Narea et al., 2024). While the Chilean ECE system has demonstrated significant advancements in enrollment rates over the past 20 years (Narea et al., 2022; OECD, 2019), these rates remain low at the nursery level that serves children from three months to two years, reaching 17.6% (Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia, 2024).

Besides notable progress in terms of enrollment rates, considerable efforts have also been made to enhance the quality of the system. From the perspective of structural quality indicators, Chile has established university-level teacher training requirements for educators working in publicly funded ECE centers and professional technical training for teaching assistants (MINEDUC, 2011). Additionally, the country has implemented technical coefficient regulations in publicly funded centers that establish differentiated criteria for Nursery (which serves children from 3 to 24 months, approximately), Lower-Middle (2 to 3 years old), Upper-Middle (3 to 4 years old), Pre-Kindergarten (4 to 5 years old), and Kindergarten levels (5 to 6 years old), supported by pedagogical teams comprising technical staff led by a qualified educator (MINEDUC, 2011). Furthermore, Chilean ECE has a curricular framework (designed in 2001 and upgraded in 2018) that establishes learning goals and teaching guidelines for all children from nursery to kindergarten levels (Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia, 2018a). From an institutional perspective, Chile modernized its ECE system by establishing the Undersecretariat of Early Childhood Education, responsible for defining policy guidelines for this educational level. The country also created the Education Quality Agency, focused on monitoring and evaluating progress regarding practices within educational establishments. Finally, Chile established the Superintendency of Education and the Intendancy of Early Childhood Education, whose objective is to oversee compliance with the basic operational requirements for early childhood centers as established in Chilean legislation (Adlerstein & Pardo, 2020; Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia, 2018b). In summary, Chile maintains a high level of regulation regarding structural quality indicators, particularly on ratios, class size and teacher education, which comprise the so-called “iron triangle” of ECE structural quality (Slot et al., 2015).

Despite the importance conferred to ECE in Chile and Latin America in the last decades, evidence on ECE quality remains limited in the region. While the majority of studies conducted in these countries have focused on pre-kindergarten and kindergarten levels (Dominguez et al., 2008; Hanno et al., 2020; Herrera et al., 2005; Leyva et al., 2015; Treviño et al., 2013), there is a growing interest in studying toddler classrooms. To date, only three studies using the CLASS-T instrument with Latin American samples have been identified: two in Ecuador (both using the same sample) (Araujo et al., 2015; Lopez Boo et al., 2019) and one in Chile (Gebauer Greve & Narea, 2021). The Ecuadorian study (n = 404) reported CLASS-T scores indicating low-to-medium quality (mean = 2.88, SD = 0.42), with moderate levels in EBS (mean = 3.63) and low quality in ESL domain (mean = 1.65) (Lopez Boo et al., 2019). They found correlations between CLASS-T and some structural factors. For example, there was a weak but significant correlation between CLASS-T total score and teachers’ years of education (r = 0.15; p < 0.10). Additionally, they found an association between CLASS-T total score and the child–caregiver ratio: classrooms below the median ratio had a slightly higher CLASS-T mean score (mean = 2.92) than those above the median (M = 2.83; p = 0.03). In contrast, the Chilean study (Gebauer Greve & Narea, 2021) (n = 16) found moderate quality levels in the sample (mean CLASS-T = 3.7; mean ESB = 4.08; mean ESL = 3.33). The authors did not find correlations between EBS or ESL scores and class size, child-to-teacher ratio or teacher education.

Other studies have analyzed the association between structural and process quality, finding mixed results. A recent study conducted in Peruvian classrooms of children from 3–6 years old did not find significant associations between CLASS scores and other quality measures (teachers’ education, teachers’ years of experience, and child-to-teacher ratios) (Hanno et al., 2020). Maldonado-Carreño et al. (2022) studied structural and process quality in pre-kinder settings in Colombia, identifying low correlations between the two dimensions of quality. In Chile, Cárcamo et al. (2014) measured the association between process quality in a small sample (N = 17) using the ITERS-R, number of adults within the classroom, and their type of professional preparation and, despite positive trends, did not find any significant correlation. Conversely, Dominguez et al. (2008) found a positive association between caregivers’ training hours and process quality in infant/toddler groups (r = 0.45). In sum, as in other parts of the world, in Chile and Latin American countries, evidence regarding the association between process and structural quality features remains inconclusive. Nevertheless, most of this evidence has been produced at older age levels (pre-kinder and kinder).

1.3. The Present Study

This study characterizes Chilean “Salas cuna” (nurseries) based on features of process and structural quality. The paper seeks to identify whether nurseries with a certain process quality profile also display a certain pattern of structural quality. To do this, following a strategy similar to Wysłowska and Slot (2020), classroom profiles were constructed based on their process quality features, and then structural quality variables of each profile were examined. This strategy allowed us to develop a more fine-grained approach to understanding how these two types of factors relate to each other in concrete classroom types, which leads to an enhanced understanding of quality in nurseries serving disadvantaged backgrounds in Chile.

Three types of structural indicators were tested: classroom resources and infrastructure, group size and ratios, and teachers’ characteristics. In this regard, the study contributes empirical evidence to address the two research gaps identified above. On the one hand, it aims to provide new evidence on the association between structural and process quality in toddler classrooms. On the other hand, the paper addresses structural and process quality in Chile, a Latin American country from the Global South, which is a less explored context in this area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

The data used in this study come from the longitudinal study First Thousand Days (Mil Primeros Días: MPD) (Narea et al., 2020), a Chilean study conducted by the Center for Advanced Studies on Educational Justice (CJE) of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. The study aims to characterize trajectories of care and education by following a cohort of 1161 children and their main caregivers in Santiago, Chile. Participants were recruited in the waiting rooms of public healthcare centers during the children’s well-child checks. The first round of data was collected in 2019 when the children were between 12 and 15 months old, and the current study was conducted using a subsample of children who were enrolled in early childhood education settings, which constituted the second most used type of care within the total sample (Narea et al., 2020).

The analytic sample of this study included 51 toddler classrooms that serve children from 12 to 24 months. These classrooms were chosen because at least one child attending them for more than 20 h a week was a participant in the MPD study. All the nursery classrooms were in the Chilean Metropolitan Region; 90% of them were public institutions, and only 10% were private. Following the Territorial Human Well-being Index (for more details, see Section 2.2 Measures and Procedures), these classrooms were in territories with an index between 0.41 and 0.84, with a mean of 0.62. This index ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 represents better territorial human well-being, and the average for the Chilean Metropolitan Region is 0.64. Within these classrooms, 152 educational agents were surveyed, including 45 teachers and 107 teacher assistants. All of them were female.

2.2. Measures and Procedures

To record selected classrooms, public and private nursery administrators were asked to participate and signed formal agreements when requested. Consent forms were signed by teaching teams and parents. Once consent forms were collected, classrooms were recorded for four hours between November 2019 and January 2020, capturing pedagogical activities, breaks, and mealtimes within the classrooms. It is important to note that this constituted an atypical period for collecting classroom data. In November, classrooms had started to reopen after being closed for 35 days (Navarro et al., 2020) due to the largest social uprising in Chile in three decades. Hence, both children and teachers were arguably experiencing high levels of stress during the data collection period. Additionally, January constitutes a vacation period in Chile, during which early childhood centers typically implement activities that differ from standard academic programming—specifically, less instructionally focused activities—compared to the remainder of the academic year.

2.2.1. Process Quality

To measure process quality, the classrooms were evaluated using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS), Toddler version (La Paro et al., 2012). The CLASS Toddler assesses quality in two domains: Emotional and Behavioral Support (EBS) and Engaged Support for Learning (ESL). These domains comprise eight dimensions rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from low (1 or 2), mid (3, 4, 5), to high (6 or 7) (see Table 1). Studies reporting CLASS results typically describe mid-level scores as middle-low when scores are near 3, and middle-high when scores are near 5 (Guedes et al., 2020; Salminen et al., 2021). In this paper, these scores are reported in the same manner.

Table 1.

CLASS-T domains, dimensions, and definitions.

The CLASS-T was administered by a certified team. The certification process was conducted by the Center for Educational Transformation (CENTRE UC), following established Teachstone procedures. CENTRE UC is the only Teachstone-certified CLASS trainer in Chile. The coding procedure comprised four segments of 20 min per classroom. To ensure the reliability and calibration of the coding process, 20% of the video recordings were independently coded a second time by a master coder. Children’s caregivers as well as pedagogical agents signed informed consent to participate in the study.

2.2.2. Structural Quality

The structural quality features analyzed in this study included three types of variables commonly measured by other scholars: (a) classroom resources and infrastructure (Barros et al., 2016), (b) group size and ratios (Slot et al., 2015; Barros et al., 2016), and (c) teachers’ education and experience (Thomason & La Paro, 2009; Slot et al., 2015; Barros et al., 2016). Data on classroom resources and infrastructure, and group size and ratios were collected by a questionnaire completed by a fieldwork professional who observed the classroom and documented the number of children and adults who were present during the observation. Data on teachers’ education and experience were provided by the teachers and assistant teachers who completed a questionnaire after the classroom recording. The variables included in the analysis are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Structural quality variables and their definitions.

In addition to process and structural quality indicators, the analysis also controlled differences by the nursery’s socioeconomic status. This was measured as follows:

- Nursery’s socioeconomic status

Territorial Human Well-being Index: The Territorial Human Well-being Index was used as a proxy of each classroom’s socioeconomic status. This indicator includes four dimensions: accessibility (to different facilities and services), environmental (environmental comfort of the surroundings, thermal amplitude, and vegetation), socioeconomic, and security. It ranges from 0 to 1, providing a number per block/square/neighborhood (or per commune) in Chile.

2.3. Analysis Strategy

The analysis consisted of two stages: 1. A latent profile analysis (LPA) to identify different profiles of classrooms in terms of their process quality. 2. A multinomial regression analysis to observe potential differences in structural quality indicators between the profiles of process quality, identifying whether classrooms with a higher process quality also have better structural quality features.

LPA allows researchers to distinguish subgroups and identify profiles of cases with similar characteristics (Linzer & Lewis, 2011) from multivariate continuous data (Clogg, 1995). This person-centered approach has been particularly useful in educational and social contexts, as it allows researchers to explore data heterogeneity and detect differentiated profiles (Collins & Lanza, 2009; Linzer & Lewis, 2011). Furthermore, by relying on probabilistic models, LPA offers greater robustness to measurement errors, facilitating informed decision-making based on the outcomes (Pastor et al., 2007).

The final number of profiles is determined by the comparison of fit statistics given by the different number of profiles, as well as theoretical expectations. For the present study, the eight dimensions from the CLASS Toddler were used for the LPA. Solutions with two to six profiles were compared, and the robustness of the final solution (three latent profiles) was tested by drawing on an alternative methodology (non-hierarchical k-means cluster analysis). Both analyses resulted in the same three profiles. The analyses were run using Stata 18.

In a second stage, multinomial regression analyses were employed to ascertain the extent to which structural indicators are associated with profile membership. Multinomial logistic regression (MLR) is used when the response variable (in this case, the CLASS Toddler profiles) is a categorical variable composed of more than two categories (El-Habil, 2012). Thus, unlike logistic regression, MLR allows for the simultaneous comparison of more than one contrast between variables (El-Habil, 2012). In this case, it allows researchers to simultaneously compare the predictability of the independent variables (structural quality features) when contrasting process quality profiles 1 and 2, 2 and 3, and 1 and 3.

3. Results

The findings of the study are reported in three different sections. First, we present descriptive statistics of the process and structural variables, including results of the CLASS Toddler average scores by dimension. Then, we report the outcomes of the latent profile analysis, describing the obtained profiles based on CLASS Toddler scores. Finally, in the third section, we present findings on the association between process and structural quality features through the MLR analysis.

3.1. Structural and Process Quality Features

Table 3 shows that process quality measured by the CLASS-T is at a low-to-moderate level. The sampled classrooms obtained, on average, moderate level scores on Emotional and Behavioral Support (EBS) dimensions, and low scores on Engaged Support for Learning (ESL) dimensions. Regarding EBS, higher average scores were observed in Positive Climate (M = 4.6; SD = 0.72) and Negative Climate (M = 6.8; SD = 0.27; higher scores represent less Negative Climate), as well as in Teacher Sensitivity (M = 4.7; SD = 0.63). In ESL, classrooms exhibited better scores in Facilitation of Learning and Development (M = 2.95; SD = 0.87), but low scores in Quality of Feedback (M = 2.09; SD = 0.67) and Language Modeling (M = 2.02; SD = 0.81). The dispersion of the scores tended to be slightly greater in ESL than in EBS dimensions, and none of the classrooms exhibited scores higher than 3.5 and 3.75 in Quality of Feedback and Language Modeling, respectively. On the contrary, it was possible to find classrooms with high-level quality in Positive and Negative Climate, alongside Teacher Sensitivity.

Table 3.

CLASS-T scores by dimension and domain. Descriptive statistics of the analytic sample.

In terms of structural quality indicators, three types of features were assessed: space and pedagogical resources, ratios and group size, and teachers’ characteristics. Regarding space and pedagogical resources, Table 4 shows that more than half of the classrooms have large spaces (54%), as well as enough lighting and control of the entrance of natural light (80%). In addition, observers indicate that nearly 40% of the classrooms have “plenty of toys and/or supplies” and, noteworthy, only 12% of the classrooms have “plenty of books”. Regarding ratios and group size, classrooms exhibit an average children-to-teacher ratio of 3.48 (SD = 2.20), and an average group size of 10.58 (SD = 4.10). Lastly, regarding teachers’ and assistants’ characteristics, both together have on average, 8.24 years of experience (SD = 3.95); nearly 54% of the teachers hold a college degree, and 41% hold a vocational tertiary education diploma. On the other hand, on average, classrooms have 64% of teacher assistants who were trained in vocational high school programs, and an average of 36% of them hold higher education certifications, either at Centros de Formación Técnica (Centers of Technical Training), Institutos Profesionales (Professional Institutes) or universities.

Table 4.

Structural quality indicators: descriptive statistics of the analytic sample by process quality profile.

3.2. Latent Profile Identification Results

The second stage of the analysis consists of identifying groups to classify classrooms in terms of their process quality, as measured by CLASS-T. As described in the previous section, on average, classrooms exhibited moderate quality on EBS dimensions, and low quality on ESL dimensions. Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) allows us to identify groups of classrooms with similar quality characteristics.

Potential LPA profile solutions comprising different numbers of profiles (two to six) were evaluated and compared using the Bayesian and Akaike information criteria (BIC and AIC), class sizes, and substantive considerations (Bray et al., 2010). In both cases, lower values indicate fit better (Celeux & Soromenho, 1996). Table 5 shows the outcomes based on the solutions for two to six profiles.

Table 5.

Fit indices for different latent profile solutions.

As shown in Table 5, the model with three latent profiles yielded the lowest AIC and BIC. Therefore, based on the fit criteria previously described, a three-profile solution was identified as the optimal fit for describing the process quality in our sample based on theory and interpretability. The solution provided substantively interpretable profiles (Bauer, 2022).

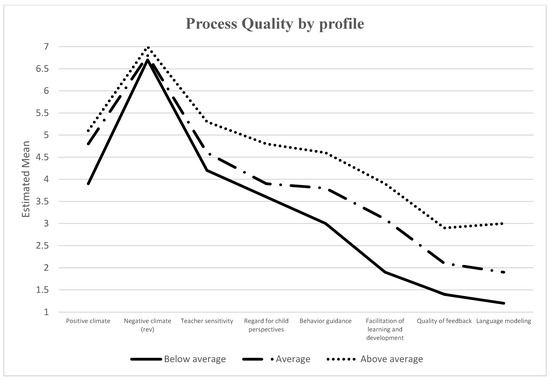

Figure 1 depicts the three-profile solution, which illustrates the variation in process quality. For the sample of 51 classrooms, approximately 31% were classified as belonging to Profile 1 (n = 16). This profile presents the lowest scores in all eight dimensions measured by the CLASS-T, which would indicate that this group of classrooms presents the lowest level of process quality. Consequently, this profile was designated as “below average”. Around 41% of the sample was classified as profile 2 (n = 21), presenting average scores for all the CLASS dimensions. This group is described as “average”. Finally, approximately 28% of the sample was classified as Profile 3 (n = 14), exhibiting higher CLASS scores, and were thus designated as “above average”. As outlined in Table 6, the average scores were clearly different among the three profiles in all eight dimensions of the CLASS. Differences among profiles were statistically significant (p < 0.01) in all dimensions, and in each case, average scores were the lowest in profile 1, the highest in profile 3, and intermediate between both in Profile 2.

Figure 1.

CLASS average scores by Profile.

Table 6.

CLASS-T scores by Profile.

In the following, the three process quality profiles are described in terms of their structural quality features. This allowed us to get a comprehensive overview of the way both types of quality indicators appear in classrooms.

3.2.1. Profile 1: Below-Average Process Quality

The first profile groups classrooms with the lowest scores in all dimensions from the two CLASS domains. Regarding the EBS domain, Table 6 depicts that classrooms obtained middle-range scores in Positive Climate (M = 3.95, SD = 0.67), Teacher Sensitivity (M = 4.23, SD = 0.42), and Regard for Child Perspectives (M = 3.64, SD = 0.49) and middle-low scores in Behavior Guidance (M = 2.98, SD = 0.47). In contrast, the three dimensions of the ESL domain exhibited low scores (Facilitation of Learning and Development (M = 1.92, SD = 0.37), Quality of Feedback (M = 1.36, SD = 0.32), and especially Language Modeling (M = 1.2, SD = 0.37)).

While statistically significant differences among profiles were observed only in a few structural quality indicators (as will be described in the next section), some trends exhibited in Table 4 are worthy of description. Regarding space and pedagogical resources, while classrooms of profile 1 exhibit fewer pedagogical resources (books, toys, and supplies) than those of profiles 2 and 3, no substantial differences were observed in terms of classroom installations (space and light access). In relation to ratio and group size indicators, these classrooms exhibited slightly greater group size and children-to-teacher ratios compared to the other two profiles, as might be expected. Lastly, classrooms grouped in profile 1 showed teachers with fewer years of working experience (M = 7.91) and a slightly greater proportion of assistants trained at secondary schools (74.4%) instead of tertiary-level education programs, as expected. However, it is noteworthy that in this profile there were more teachers with college degrees than in profile 3, which is the one with better process quality indicators.

3.2.2. Profile 2: Average Process Quality

Profile 2 classrooms obtained scores between profiles 1 and 3 in all eight CLASS-T dimensions. These classrooms were characterized by exhibiting mid-level scores in all EBS dimensions (except for Negative Climate, in which all profiles have very high-level scores). In the case of Positive Climate (M = 4.77, SD = 0.51) and Teacher Sensitivity (M = 4.67, SD = 0.50) dimensions, scores were situated near to a mid–high range. Regarding the ESL domain, classrooms in this profile exhibited a mid–low level in Facilitation of Learning and Development (M = 3.10, SD = 0.36), and a low level in Quality of Feedback (M = 2.13, SD = 0.37) and Language Modeling (M = 1.9, SD = 0.42), but almost one point higher than profile 1 classrooms.

Structural quality indicators in these classrooms were consistent with what is expected in space and pedagogical resources, and group size and ratios, though slightly atypical in relation to teacher characteristics. Regarding space and pedagogical resources, profile 2 classrooms exhibited an intermediate number of pedagogical resources (books, toys) compared to profiles 1 and 3. Likewise, the number of times that observers indicate that the space of these classrooms is “large”, was slightly smaller than in the other two profiles (45%), but this proportion was the highest among the three profiles regarding the light access and control (85%). Ratio and group size indicators maintained the trend: smaller group size and children-to-teacher ratio than profile 1, but slightly greater than profile 3. Finally, pedagogical agents in profile 2 exhibited the best educational credentials of the three profiles: most of the teachers held a college degree (70.6%), and classrooms had a greater proportion of teacher assistants holding vocational tertiary-level diplomas (44.1%).

3.2.3. Profile 3: Above-Average Process Quality

Profile 3 classrooms exhibited the best scores in all the dimensions of both CLASS Toddler domains. Performance in EBS dimensions was broadly middle-to-high scores. While dimensions such as Positive Climate (M = 5.07, SD = 0.51) and Teacher Sensitivity (M = 5.27, SD = 0.55) obtained middle-to-high scores, Regard for Child Perspectives (M = 4.79, SD = 0.54) and Behavior Guidance scores (M = 4.55, SD = 0.38) were situated from the middle toward the middle–high level. Nevertheless, the main difference between this profile and profiles 1 and 2 was its ESL scores. While Facilitation of Learning and Development (M = 3.91, SD = 0.47) almost achieved a middle-range score, Quality of Feedback (M = 2.88, SD = 0.29) and Language Modeling (M = 3.04, SD = 0.48) approached middle-low level scores.

Like the other profiles, the structural quality characteristics of profile 3 classrooms aligned with anticipated patterns in terms of space and pedagogical resources, as well as group size and ratios, while displaying somewhat unconventional patterns regarding teacher characteristics. Profile 3 classrooms had more books and toys than profiles 1 and 2, as well as more space. Similarly, they also had smaller group sizes and children-to-teacher ratios. However, contrary to expectations, profile 3 classrooms had fewer teachers holding college degrees and fewer assistants per classroom holding tertiary-level education diplomas than profile 2.

3.3. Process and Structural Quality: How Do They Correlate?

The final section of the findings aimed at identifying the possible associations between process and structural quality features. To do this, multinomial regression analysis was carried out to identify the extent to which the variability in structural indicators was associated with the probability of belonging to any of the three process quality profiles. Three models were estimated, each one devoted to the three groups of structural quality indicators: Model 1 (Table 7) estimates the probability of belonging to process quality latent profiles, conditional on space and pedagogical resources, and models 2 and 3 (Table 8 and Table 9) repeat this exercise with ratios and group size, and Teachers’ characteristics variables, respectively. Additionally, the Territorial Human Well-being Index was included in each of the three models to control for the effects of the socioeconomic status of the classrooms. It is important to note that, given the small sample size, trends reported in this section might suggest associations between variables, yet the size of the sample creates substantial uncertainty around the magnitude of these effects. Therefore, results should be interpreted carefully and only as promising trends that need to be further studied using a more robust sample design.

Table 7.

Model 1. Profile (below average, average, or above average) conditional on the classroom space and pedagogical resources.

Table 8.

Model 2. Profile (below average, average, or above average) conditional on the group size and adult/child ratio.

Table 9.

Model 3. Profile (below average, average, or above average) conditional on teachers’ characteristics.

Statistically significant differences among process quality profiles were found only in a few structural indicators, yet not always in the expected direction. Regarding space and pedagogical resources, Table 7 shows weak statistically significant differences in classroom space between above-average and average profiles (β = 1.64, OR = 5.16, p = 0.06). This trend suggests that having large space increases the classrooms’ chance of being in the highest process quality profile instead of the average profile. Likewise, there are marginally significant differences between above and below-average profiles in toys and/or supplies (β = 1.74, OR = 5.68, p = 0.08), which indicates that classrooms having plenty of toys and supplies have a greater chance of belonging to a better process quality profile.

While differences regarding ratio and group size indicators were in the expected direction (that is, as process quality improved, average group sizes and children-to-teacher ratios tend to decreased), Model 2 coefficients (Table 8) show that there are no statistically significant differences between process quality profiles conditional on group size or children-to-adults ratios.

Finally, in relation to teachers’ characteristics, weak statistically significant differences were found in teachers’ and assistants’ pre-service training. Regarding teachers’ education, findings suggest that teachers with college degrees have a greater chance of working in Average process quality classrooms (profile 2), rather than in below-average (profile 1) (β = 2.56, OR = 25.49, p = 0.07) and above-average process quality classrooms (profile 3) (β = −3.29, OR = 0.04, p = 0.01). Likewise, Table 9 shows that there is a greater probability of having more teacher assistants trained in higher education institutions in Average quality classrooms (Profile 2) than in below-average quality classrooms (profile 1) (β = 0.05, OR = 1.05, p = 0.04). As it was expected that classrooms with better process quality were led by better trained teachers, these outcomes suggest trends which are partially in the expected direction. Nevertheless, β and OR coefficients should be interpreted carefully given the high uncertainty caused by the small sample size.

4. Discussion

In this study, we characterized the process and structural quality of Chilean nurseries by producing three classroom profiles based on their process quality features (CLASS Toddler scores), which were later compared in terms of their structural quality features. Profile 1 (below average) exhibited middle–low-to-middle-range scores in Emotional and Behavioral Support (EBS) dimensions, and very low scores in Engaged Support for Learning (ESL) dimensions. In profile 2 (average), scores rose to the middle or middle–high range in EBS dimensions, and while ESL scores remained low, these are nearly 1 point higher than profile 1. Profile 3 classrooms (above average) obtained average middle–high scores in EBS dimensions and middle or middle-low scores in ESL dimensions. Despite the sharp differences in terms of process quality, no substantial differences were observed in relation to structural quality features among these three profiles. It is important to analyze these results in relation to the findings of previous studies.

4.1. Examining CLASS Toddler Outcomes Based on Their Context

Broadly, CLASS Toddler scores exhibited by the classrooms in this sample were lower than those observed in studies carried out in other contexts, including Global North countries and China. This is particularly clear in the case of the ESL domain, although it also occurs in the case of the EBS domain. In the case of ESL (M = 2.35), these scores are lower than the observed in studies conducted in Finland (Salminen et al., 2021), Canada (Sokolovic et al., 2022), Portugal (Salminen et al., 2021), Norway (Buøen et al., 2021), the Netherlands (Wysłowska & Slot, 2020), and China (Luo et al., 2024), in which scores fluctuate between 3.17 and 3.57. In the EBS domain (M = 4.79), the situation is similar, as scores of samples studied in Finland (Salminen et al., 2021), the United States (Castle et al., 2019), Canada (Sokolovic et al., 2022), Norway (Buøen et al., 2021), and Poland (Wysłowska & Slot, 2020) exhibited scores that fluctuate between 5.58 and 6.02. Nonetheless, in this case, the scores of the current study were similar to those observed in samples from the United States (4.82) (La Paro et al., 2014) and China (4.81) (Luo et al., 2024), and better than a sample from Portugal (4.53) (Salminen et al., 2021).

However, it is interesting to enrich this discussion by focusing on profile 3 CLASS-T scores only, which group classrooms with the best scores in the sample. Average scores of this profile tend to be better aligned with average scores reported in countries from the Global North and China. As observed in the findings section, Profile 3 scores in EBS and ESL rise to 5.33 and 3.28, respectively. Looking at these classrooms only, average scores in ESL were similar to those obtained in samples from China (Luo et al., 2024) and Canada (Sokolovic et al., 2022), and better than samples from the United States (La Paro et al., 2014), Portugal (Salminen et al., 2021), and Poland (Wysłowska & Slot, 2020). In the case of EBS, Chilean classrooms in this study were similar to a sample from the Netherlands (Wysłowska & Slot, 2020), and they exhibited scores above reports from Portugal (Salminen et al., 2021) and the United States (La Paro et al., 2014).

Considering these findings, two things are important to point out. On the one hand, the findings from the studied Chilean toddler classrooms are broadly lower than those commonly obtained by studies conducted in countries from the Global North. Considering that CLASS is a tool developed in the United States, its standards were conceptually designed based on that context. Thus, it is not surprising that Chilean classrooms struggle in some cases to meet these standards. On the other hand, however, it is important to note that, under certain circumstances, pedagogical interactions that take place in vulnerable contexts of a Global South country like Chile, can be similar to those implemented in classrooms from the Global North.

Indeed, it is worth noting that higher CLASS-T scores of profile 3 classrooms come closer to the thresholds of the quality studied in pre-kinder and toddler classrooms (Hatfield et al., 2016; Bichay-Awadalla, 2019). According to this literature, the association between process quality and child cognitive and socioemotional outcomes may not be linear and, instead, this relationship might strengthen from a certain threshold of quality (Hatfield et al., 2016). While these may vary among studies and classroom levels (Burchinal et al., 2010; Hatfield et al., 2016; Bichay-Awadalla, 2019), incipient evidence in toddler settings suggests that in those classrooms scoring at or above 5.5 in EBS and 3.5 in ESL, the effects of process quality on socioemotional development are stronger and more beneficial compared to the effects detected below those thresholds (Bichay-Awadalla, 2019). While profile 3 classrooms did not reach these average scores, their scores came notably closer than those of the other two classroom profiles. Therefore, according to this evidence, this group of classrooms nearly meets quality standards that have proven to be highly beneficial for children’s learning.

It is also important to analyze these findings in relation to other studies carried out in similar contexts. The CLASS-T means reported in this paper (EBS: 4.79; ESL: 2.35) were greater than other figures from a study in Ecuador (EBS: 3.63; ESL: 1.65) (Lopez Boo et al., 2019), but they differed from those reported in another study conducted in Chile (EBS: 4.08; ESL: 3.33) (Gebauer Greve & Narea, 2021). The latter found better scores in ESL, but lower scores in EBS. In sum, the present study contributes to enriching incipient evidence collected with CLASS Toddler in Latin American countries, which accounts for a different reality regarding pedagogical interactions compared to countries from the Global North where these studies are more common.

Likewise, it is important to examine the CLASS outcomes of this sample considering the context in which the data were collected. As explained in the Methods section, data were collected during an unfavorable moment for evaluating classrooms using the CLASS, as, on the one hand, educational communities were subjected to elevated stress levels and, on the other, part of the data was collected during the holiday season. These factors may have influenced the quality of pedagogical interactions observed, particularly given CLASS’s predominantly instructional focus (see, for instance, the differences in CLASS Toddler scores between academic and free play activities documented in Guedes et al. (2020)). Therefore, it is essential to observe and evaluate measures of this nature—based on fixed standards—within their specific contexts of implementation.

4.2. Structural and Process Quality: An Unclear Relationship

The study results show that, despite sharp differences in process quality among the three profiles created through Latent Profile Analysis, these profiles did not appear to differentiate as distinctly with respect to their structural quality indicators. Thus, while trends consistent with expectations are observed in the descriptive data of structural quality characteristics among the three profiles, only limited and weak statistically significant differences are found between them. This finding is consistent with part of the international evidence compiled on this matter.

First, no significant differences were observed between profiles regarding group size and ratio variables. This is consistent with studies that have found no effects of either group size (Slot et al., 2015) or child-to-teacher ratios on process quality variables (Barros et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2017; Slot et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the descriptive analysis suggested trends aligned with expectations, namely, that classrooms with higher process quality exhibited, on average, smaller group sizes and lower child-to-teacher ratios.

Second, the study revealed marginal associations between process quality and teacher training indicators, albeit not always in the anticipated direction. Specifically, there was a greater chance of finding better-trained educators in average process-quality classrooms (Profile 2) rather than in above and below-average process-quality classrooms. As explained in the introduction, the evidence concerning the impact of educator qualification levels on process quality remains inconclusive. While certain studies identified a moderate effect (Lopez Boo et al., 2019; Slot et al., 2015), others did not show significant correlations (Castle et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2024), although more consistent positive associations were documented regarding the possession of specialized early childhood education degrees (Barros et al., 2016; Castle et al., 2019). In this context, it is crucial to acknowledge that, in Chile, educators and teaching assistants are legally required to possess specialized degrees or diplomas in early childhood education, rendering this a consistent characteristic across most Chilean classrooms.

In sum, the present study adds evidence to the incipient body of research conducted in Latin America regarding the correlation between process and structural quality in early childhood classrooms. Like previous studies, this study did not show strong evidence regarding the relationship between both components of quality (Cárcamo et al., 2014; Dominguez et al., 2008; Hanno et al., 2020; Maldonado-Carreño et al., 2022). As reported by other international studies (Buøen et al., 2021; Lopez Boo et al., 2019; Wysłowska & Slot, 2020) in the case of Chilean classrooms, this lack of association between the two dimensions may be attributed to the high degree of standardization of structural quality factors. In Chile, aspects concerning group size, child-to-teacher ratios, and teachers’ training are highly regulated, establishing minimum requirements for all classrooms nationwide (MINEDUC, 2011). Although the legislation allows for variability in ratios and group sizes above these minimum standards, this variability appears to be limited on average. In fact, the data from this study show that, even though ratios range from 1 to 12 children per adult in the examined classrooms, the standard deviation of these ratios is 2.20 children per adult. In summary, this suggests that these regulations are effective, and that child-to-teacher ratios and group sizes do not appear to constitute highly relevant factors for explaining differences in process quality at present.

Alternatively, this lack of statistically significant association may be due to methodological reasons. As shown in Table 6, trends in the expected direction can be observed regarding class size and ratios among the three process quality profiles. Thus, one possible explanation for this absence of association is the small sample size used in this study. As stated in the final section of this paper, this is a limitation that needs to be addressed in future research. However, this alternative explanation is not necessarily contradictory to the argument presented above.

In the case of teacher education, the requirements of a college degree and specialized technical–professional diplomas for educators and assistants, respectively, are also part of the minimum requirements for teaching in establishments officially recognized by the Chilean Ministry of Education (MINEDUC, 2011). However, this regulation is relatively recent, so there are senior teachers trained under the old legislation who are still actively working in the system. In the case of assistants, the law establishes that they can be trained in specialized vocational programs, either in secondary schools or in tertiary education institutions. Although there is no evidence available on differences in the teaching effectiveness of either type of program, there are studies that show important differences in the depth of the pedagogical focus of tertiary-level programs compared to secondary ones (Viviani & Rodríguez, 2020).

In sum, this study offers useful insights regarding how the process and structural quality interrelate within Chilean classrooms, characterized by diverse quality levels, though predominantly serving socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts. The findings align with internationally recognized standards of early childhood education quality, such as the OECD quality framework (OECD, 2018), which emphasizes the relevance of both structural and process quality. Thus, this study contributes useful input for understanding how quality concepts produced in the Global North take shape in the Global South.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights for examining the relationship between the process and structural quality in Chile, it is essential to continue developing research in this field using larger and representative samples. Additionally, future studies should analyze the relationship between structural and process quality indicators from a longitudinal perspective in order to establish causality. While the First Thousand Days study has a longitudinal design regarding child development and home-based care practices, we were unable to continue collecting classroom data. Therefore, research addressing both methodological issues would enable the confirmation or redirection of the hypotheses raised in this study, with the aim of strengthening policies oriented toward enhancing educational quality in Chile.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G. and M.N.; methodology, P.S.-R., F.G., C.A. and M.J.L.; software, P.S.-R. and C.A.; validation, F.G., M.N. and P.S.-R.; formal analysis, P.S.-R. and C.A.; data curation, F.G. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G., C.A., P.S.-R. and M.J.L.; writing—review and editing, F.G. and M.N.; project administration, M.N.; funding acquisition, M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by AGENCIA NACIONAL DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y DESARROLLO, grant number ANID PIA CIE160007.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Scientific Ethical Committee of PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE CHILE (200514007) in 20 August 2019 and has been updated for each subsequent wave of data collection.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the teachers and parents of the children involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to confidentiality agreements with the participants.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all families and teachers who devoted time to participate in the First Thousand Days study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECE | Early Childhood Education |

| EBS | Emotional and Behavioral Support |

| ESL | Engaged Support for Learning |

| CLASS-T | Classroom Assessment Scoring System, Toddler version |

References

- Adlerstein, C., & Pardo, M. (2020). Otra cosa es con sistema! En camino hacia una Educacion Parvularia de calidad. In M. T. Corvera, & G. Munoz (Eds.), Horizones y propuestas para transformar el sistema educativo chileno (pp. 22–51). Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, M. C., Lopez Boo, F., Novella, R., Schodt, S., & Tomé, R. (2015). La calidad de los Centros Infantiles del Buen Vivir en Ecuador. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/en/quality-centros-infantiles-del-buen-vivir-ecuador (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Barros, S., Cadima, J., Bryant, D. M., Coelho, V., Pinto, A. I., Pessanha, M., & Peixoto, C. (2016). Infant child care quality in Portugal: Associations with structural characteristics. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 37, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J. (2022). A primer to latent profile and latent class analysis. In M. Goller, E. Kyndt, S. Paloniemi, & C. Damsa (Eds.), Methods for researching professional learning and development: Challenges, applications and empirical illustrations (pp. 243–268). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bichay-Awadalla, K. (2019). Examining the Role of varying levels of classroom quality for toddlers in early head start and subsidized child care programs: Understanding threshold effects (order no. 22615516). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2311654516). Available online: https://scholarship.miami.edu/esploro/outputs/doctoral/Examining-the-Role-of-Varying-Levels/991031447559302976 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Bichay-Awadalla, K., & Bulotsky-Shearer, R. J. (2022). Examining the factor structure of the classroom assessment scoring system toddler (class-t) in early head start and subsidized child care classrooms. Early Education and Development, 33(2), 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, B. C., Lanza, S. T., & Collins, L. M. (2010). Modeling relations among discrete developmental processes: A general approach to associative latent transition analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 17(4), 541–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, P. R., Yoshikawa, H., & Boller, K. (2011). Quality of early childhood development programs in global contexts: Rationale for investment, conceptual framework and implications for equity and commentaries. Social Policy Report, 25(2), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buøen, E. S., Lekhal, R., Lydersen, S., Berg-Nielsen, T. S., & Drugli, M. B. (2021). Promoting the quality of teacher-toddler interactions: A randomized controlled trial of “thrive by three” in-service professional development in 187 norwegian toddler classrooms [original research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 778777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchinal, M., Vandergrift, N., Pianta, R., & Mashburn, A. (2010). Threshold analysis of association between child care quality and child outcomes for low-income children in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25(2), 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, S., Williamson, A. C., Young, E., Stubblefield, J., Laurin, D., & Pearce, N. (2019). Teacher–child interactions in early head start classrooms: Associations with teacher characteristics. In Group care for infants, toddlers, and twos (pp. 115–130). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cárcamo, R. A., Vermeer, H. J., De la Harpe, C., van der Veer, R., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2014). The quality of childcare in Chile: Its stability and international ranking. Child & Youth Care Forum, 43(6), 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celeux, G., & Soromenho, G. (1996). An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification, 13(2), 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clogg, C. C. (1995). Latent class models. In G. Arminger, C. Clogg, & M. E. Sobel (Eds.), Handbook of statistical modeling for the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 311–359). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2009). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, P., Moreno, L., Narvaez, L., Herrera, M. O., & Mathiesen, M. E. (2008). Prácticas pedagógicas de calidad. Informe final [Teaching practices of quality. Final report]. Ministerio de Educación de Chile.

- El-Habil, A. M. (2012). An application on multinomial logistic regression model. Pakistan Journal of Statistics and Operation Research, 8, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer Greve, M. A., & Narea, M. (2021). Calidad de las interacciones entre educadoras y niños/as en jardines infantiles públicos en Santiago. Psykhe, 30(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, C., Cadima, J., Aguiar, T., Aguiar, C., & Barata, C. (2020). Activity settings in toddler classrooms and quality of group and individual interactions. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 67, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanno, E. C., Gonzalez, K. E., Lebowitz, R. B., McCoy, D. C., Lizárraga, A., & Korder Fort, C. (2020). Structural and process quality features in Peruvian early childhood education settings. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 67, 101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, B. E., Burchinal, M. R., Pianta, R. C., & Sideris, J. (2016). Thresholds in the association between quality of teacher–child interactions and preschool children’s school readiness skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 36, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M. O., Elena, M. M., Manuel, M. J., & Recart, I. (2005). Learning contexts for young children in Chile: Process quality assessment in preschool centres. International Journal of Early Years Education, 13(1), 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B. Y., Fan, X., Wu, Y., & Yang, N. (2017). Are structural quality indicators associated with preschool process quality in China? An exploration of threshold effects. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 40, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Paro, K. M., Hamre, B., & Pianta, R. (2012). Classroom assessment scoring system, manual toddler. Teachstone. [Google Scholar]

- La Paro, K. M., Williamson, A. C., & Hatfield, B. (2014). Assessing quality in toddler classrooms using the CLASS-Toddler and the ITERS-R. Early Education and Development, 25(6), 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.-N., Schaack, D. D., & Setodji, C. M. (2015). Identifying baseline and ceiling thresholds within the qualistar early learning quality rating and improvement system. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 30, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyva, D., Weiland, C., Barata, M., Yoshikawa, H., Snow, C., Treviño, E., & Rolla, A. (2015). Teacher–child interactions in Chile and their associations with prekindergarten outcomes. Child Development, 86(3), 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, D. A., & Lewis, J. B. (2011). poLCA: An R package for polytomous variable latent class analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 42(10), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Boo, F., Dormal, M., & Weber, A. (2019). Validity of four measures of child care quality in a national sample of centers in Ecuador. PLoS ONE, 14(2), e0209987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L., Qiu, Y., Lyu, S., Ge, H., & Liu, H. (2024). Variation in the quality of teacher–child interactions in Chinese toddler classrooms. Early Education and Development, 35(8), 1847–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Carreño, C., Yoshikawa, H., Escallón, E., Ponguta Liliana, A., Nieto, A. M., Kagan, S. L., Rey-Guerra, C., Cristancho, J. C., Mateus, A., Caro, L. A., Aragon, C. A., Rodríguez, A. M., & Motta, A. (2022). Measuring the quality of early childhood education: Associations with children’s development from a national study with the IMCEIC tool in Colombia. Child Development, 93(1), 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINEDUC. (2011). Decreto nº315: Reglamenta requisitos de adquisición, mantención y pérdida del Reconocimiento Oficial del Estado a los establecimientos educacionales de educación parvularia, básica y media. Available online: https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1026910 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Mortensen, J. A., & Barnett, M. A. (2015). Teacher–Child Interactions in Infant/Toddler Child Care and Socioemotional Development. Early Education and Development, 26(2), 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narea, M., Abufhele, A., Telias, A., Alarcón, S., & Solari, F. (2020). Mil Primeros Días: Tipos y calidad del cuidado infantil en Chile y su asociación con el desarrollo infantil. 3. Available online: https://centrojusticiaeducacional.uc.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/estudios-n3.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Narea, M., Godoy, F., & Treviño, E. (2022). Background on continuities and discontinuities in the transition from early childhood education to primary: The Chilean case. In A. Urbina-García, B. Perry, S. Dockett, D. Jindal-Snape, & B. García-Cabrero (Eds.), Transitions to school: Perspectives and experiences from Latin America. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narea, M., Treviño, E., Alarcón, S., López, M. J., & Soto, P. (2024). Guarderías informales en la primera infancia: Experiencias internacionales y una propuesta para Chile. Propuestas para Chile, 231. Available online: https://politicaspublicas.uc.cl/publicacion/capitulo-vii-guarderias-informales-en-la-primera-infancia-experiencias-internacionales-y-una-propuesta-para-chile/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Navarro, L., González, L. E., & Espinoza, Ó. (2020). El sector educación bajo el estallido social y la pandemia. In P. Díaz-Romero, A. Rodríguez, & A. Varas (Eds.), Chile en cuarentena: Causas y efectos de la crisis política y social (pp. 177–224). Ediciones SUR. Available online: https://barometro.sitiosur.cl/barometros/chile-en-cuarentena-causas-y-efectos-de-la-crisis-politica-y-social (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- OECD. (2018). Engaging young children: Lessons from research about quality in early childhood education and care (startng strong). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/engaging-young-children_9789264085145-en.html (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- OECD. (2019). Education at a glance 2019: OECD indicators. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2024). Education at a glance: OECD indicators. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, D. A., Barron, K. E., Miller, B. J., & Davis, S. L. (2007). A latent profile analysis of college students’ achievement goal orientation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32(1), 8–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo-Escudero, F., LoCasale-Crouch, J., & Turnbull, K. L. P. (2021). Caregiver ability to notice and enact effective interactions in early care classroom settings. Teaching and Teacher Education, 97, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, J., Guedes, C., Lerkkanen, M.-K., Pakarinen, E., & Cadima, J. (2021). Teacher–child interaction quality and children’s self-regulation in toddler classrooms in Finland and Portugal. Infant and Child Development, 30(3), e2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slot, P. L., Boom, J., Verhagen, J., & Leseman, P. P. M. (2017). Measurement properties of the CLASS Toddler in ECEC in The Netherlands. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 48, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slot, P. L., Leseman, P. P. M., Verhagen, J., & Mulder, H. (2015). Associations between structural quality aspects and process quality in Dutch early childhood education and care settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 33, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolovic, N., Brunsek, A., Rodrigues, M., Borairi, S., Jenkins, J. M., & Perlman, M. (2022). Assessing quality quickly: Validation of the Responsive Interactions for Learning—Educator (RIFL-Ed.) measure. Early Education and Development, 33(6), 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia. (2018a). Bases Curriculares Educación Parvularia. Ministerio de Educación. [Google Scholar]

- Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia. (2018b). Trayectorias, avances y desafíos de la Educación Parvularia en Chile: Análisis y balance de la política pública 2014–2018. Available online: https://parvularia.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Trayectorias-avances-y-desafios.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia. (2024). Informe de Caracterización de la Educación Parvularia 2023. Available online: https://parvularia.mineduc.cl/recursos/informe-de-caracterizacion-ep-2023/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Thomason, A. C., & La Paro, K. M. (2009). Measuring the quality of teacher–child interactions in toddler child care. Early Education and Development, 20(2), 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, E., Toledo, G., & Gempp, R. (2013). Calidad de la educación parvularia: Las prácticas de clase y el camino a la mejora [Preschool education quality: Teacher practices and the path to improvement]. Pensamiento Educativo. Revista de Investigación Educacional Latinoamericana, 50(1), 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2024). Early childhood care and education: Landscape review 2010–2022. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Viviani, M., & Rodríguez, J. P. (2020). Análisis de los roles y responsabilidades de las técnicos en educación parvularia en el nivel sala cuna: Una contribución a su formación inicial. Calidad en la educación. [Google Scholar]

- Wysłowska, O., & Slot, P. L. (2020). Structural and process quality in early childhood education and care provisions in Poland and the Netherlands: A cross-national study using cluster analysis. Early Education and Development, 31(4), 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).