Abstract

Learning is occurring increasingly online, often asynchronously, and sometimes that presents a barrier to instructional delivery on metacognitive behaviors that might easily be modeled in traditional classrooms. However, such metacognitive behaviors are essential to engaging deeply with academic texts. The research team involved in this paper is part of ongoing design-based research exploring the use of social annotation to support students as metacognitive readers of digital, academic texts in online asynchronous contexts. In the most recent iteration of this research, the authors designed asynchronous instruction on metacognitive reading using the gradual release of responsibility (GRR) framework. This paper provides rich descriptions of instructors’ instructional moves to scaffold and support students as metacognitive readers of digital, academic texts in asynchronous online classes. Future research should explore the efficacy of GRR as a pedagogical approach used online.

1. Introduction

Prior to the pandemic, graduate literacy courses were increasingly offered online, and the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the process of transitioning more in-person classes to online (Gallagher & Palmer, 2020; Seaman et al., 2018). Given the rising demand for online teaching, instructors across domains are seeking innovative teaching models that effectively support online learning (Groth et al., 2009).

This paper reports on a learning design developed as part of ongoing design-based research (DBR) (Reinking & Bradley, 2008) exploring the use of social annotation to support students as metacognitive readers of digital, academic texts in online asynchronous learning. All prior publications about this research have, naturally, focused on participant data and evaluation of the learning design (see Adams & Wilson, 2020; Adams et al., 2022, 2023; Wilson et al., 2024). Such focus often necessitated limiting description of the teaching that occurred during implementation of the learning design, both for clarity of purpose and to adhere to publication page limits. This paper seeks to provide a richer description of the components of our ongoing research that are often abbreviated when reporting results.

Specifically, as part of DBR, we theorized that the gradual release of responsibility (GRR) framework (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983) might be useful for developing graduate students’ metacognition and comprehension of academic texts given its efficacy in literacy education (e.g., Brown et al., 1995; Reutzel et al., 2005). The GRR framework was originally theorized and developed in response to Durkin’s (1978) study findings: little reading comprehension instruction was occurring in classrooms, rather students were completing assignments such as question-responsive activities. GRR is widely used in literacy instruction but has also been used across other educational domains since its inception over 30 years ago (Pearson et al., 2019). The purpose of this article is to provide rich descriptions of asynchronous instructional moves implemented within a GRR framework that could be used by online instructors across domains to support students’ learning. As such, we ask: How can the GRR framework be implemented as a pedagogical approach in asynchronous classes to support metacognitive reading?

In the sections that follow we review the literature on metacognition, online reading and learning, social annotations, and gradual release of responsibility. Then we describe our DBR, including previous iterations and the learning design under study. In the results, we provide rich descriptions of the instructors’ instructional moves within the GRR framework. Finally, in the discussion we offer implications for practice and an articulation of our future inquiry related to this DBR.

2. Literature Review

Metacognition, or thinking about one’s thinking, supports comprehension as readers demonstrate control of their thinking through strategies such as asking and answering questions, making inferences, and monitoring the text (N. K. Duke et al., 2011). Flavell (1993) defined metacognition as “…knowledge or cognitive activity that takes as its object or regulates any aspect of the cognitive enterprise” (p. 150). As such, metacognition is a construct that has broad applicability in higher education. It has become a defining characteristic of active learners who exercise control over the learning process (Ward & Butler, 2019; Young & Fry, 2008). However, college and university instructors often encounter students with varying levels of knowledge about how they learn (Karpicke et al., 2009; Ku & Ho, 2010). Some students are active and self-directed; they know how they learn and can strategically apply that knowledge across varied learning contexts. Other students might have some understanding of their learning strengths and weaknesses but lack the skills to adequately regulate their learning. Still others may be passive learners with minimal awareness of how they learn and how to regulate their learning (Young & Fry, 2008).

This disparity in metacognitive skill is further complicated by the prevalence of screen reading in higher education learning contexts. Most learning management systems adopted by colleges and universities include textbook integration tools that allow students to read embedded digital versions of assigned texts. Yet, reading on a screen differs from reading texts in hard copy (Coiro, 2003; Jian, 2022). Students must not only decode while reading digital texts, but also navigate myriad multimodal text features and critically evaluate an abundance of supplemental sources in order to make meaning from what they read (Coiro, 2003). Students also deploy different strategies when reading on a screen versus reading hard-copy texts (Davis & Neitzel, 2012; Liu, 2005). Ackerman and Lauterman (2012) found that participants reading on paper comprehended better, were more efficient in learning under time pressure, and exhibited less overconfidence. They concluded that “the primary differences between the two study media are not cognitive but rather metacognitive” (Ackerman & Goldsmith, 2011, p. 18). Though use of digital tools and resources is on the rise in both K-12 and university settings (National Center for Education Statistics, 2021; Sage et al., 2019), there remains a dearth of research regarding differences in metacognition between the mediums and limited extant research is overall inconclusive (Jian, 2022). Through meta-analyses generally support this idea, there has been work that identified null results (Schwabe et al., 2022) or even benefits to digital reading because of the multimodal digital tools (Clinton-Lisell et al., 2023; Goodwin et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2020; Schwabe et al., 2022).

The fact remains that students’ use of metacognitive reading strategies is vital to the development of the higher order thinking skills necessary to understand complex academic texts (Conley & French, 2014; Mokhtari & Reichard, 2002; Veine et al., 2020). This often requires that instructors embed metacognitive instruction into their teaching (Jiang et al., 2016; Zohar & Lustov, 2018). However, the increasing regularity with which learning occurs in online, often asynchronous, environments presents a barrier to instructional delivery on metacognitive behaviors that might easily be modeled in traditional classrooms (Adams et al., 2022, 2023; Wilson et al., 2024). We have engaged in multiple studies that work towards the transfer of face-to-face metacognitive scaffolding to the online learning environment, through explicit video and written instruction (Adams et al., 2023; Wilson et al., 2024). As a result, educators are actively seeking better instructional techniques to facilitate learning in online asynchronous contexts (Groth et al., 2009). Social annotation has been proposed as one avenue for improving students’ comprehension when reading academic texts (Johnson et al., 2010). Social annotation is a method of interactive reading online that enables students to annotate texts simultaneously with others (Glover et al., 2007). As students work on the same text, their individual sense making (Kintsch, 2013) and collective knowledge construction and revision (Kendeou et al., 2014; Morales et al., 2022) can be observed.

Chiu (2008) suggested that practices like social annotation offer a form of “social metacognition” that helps “group members monitor and control one another’s knowledge, emotions and actions” (p. 422). In a social metacognitive constructivist framework, social metacognition extends the ideas to increase “the visibility of one another’s metacognition” and improve “individual cognition, resulting in reciprocal scaffolding and greater motivation” (Chiu & Kuo, 2010, p. 322). Kalir et al. (2020) found that students believed their peers’ annotations helped them comprehend, engage, and interact with text with greater depth as a result of the collaborative nature of the process. Gao (2013) indicated that students who used social annotation were able to focus on more specific, rather than general, information which supported their comprehension. Multiple studies have also observed higher levels of student participation when using social annotation compared to traditional discussion boards (e.g., Adams & Wilson, 2020; Sun & Gao, 2017).

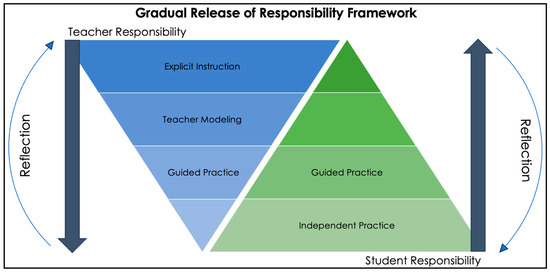

Graduate students participating in this study received direct instruction in online social annotation through the platform Perusall (www.perusall.com, accessed 1 May 2024) to make meaning from text using a GRR framework. The instruction was designed by the researchers to assure continuity across institutions; it occurred asynchronously, with details included in the methods section. GRR refers to the process in which students become more accountable for their work as they develop experience with the task (Durkin, 1978). There are five stages of GRR: (1) explicit instruction, where the teacher directly teaches what, how, when and why to use the strategy; (2) the teacher modeling stage where the teacher walks students through the strategy using a think-aloud or explicit instruction; (3) the guided practice stage where the teacher facilitates students’ interactions with the text as they apply what they learned; (4) the independent practice stage, where students are tasked to use the strategy on their own; and (5) reflection, when teacher and students reflect on their performance to decide the next steps for instruction (Baumann & Schmitt, 1986; Pearson & Gallagher, 1983) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The GRR Framework. (Fisher & Frey, 2008a).

Students and teachers may cycle through these phases nonlinearly—they can “move back and forth between each of the components as they master skills, strategies, and standards” (Fisher, 2008, p. 2). The non-linear nature of GRR is particularly important as educators consider increasingly complex tasks, texts, and learning contexts (Webb et al., 2019).

The following section details the most recent revision to our social annotation learning design. During this implementation, we focused on identifying and enacting explicit moves the instructor could make to better support students in engaging deeply with academic texts. The section describes the data collected on the teaching practices of two instructors and the process by which we analyzed the data to develop an asynchronous model of GRR.

3. Methodology

This study utilized DBR to explore how the gradual release of responsibility framework could be implemented in an asynchronous online class to support metacognitive reading. The primary objective of DBR is to examine the relationship between the theoretical underpinnings of a learning design and its efficacy to promote student learning (Reinking & Bradley, 2008). DBR is powerful for pragmatic education research because it necessitates revising a learning design until it meets the needs of students (Gravemeijer & Cobb, 2006). Specific to our field, scholars have called for more DBR methodologies that promote formative, flexible, and contextually situated conceptions of literacy (Mills, 2010). This orientation to the research compels us to bring our theoretical knowledge and practice into conversation with one another to develop the best design to support our graduate students.

To that end, this study is part of a larger design-based project that is currently in its fourth year. The project began by looking at the metacognitive behaviors of students during reading and has since evolved to investigate how course design, assignment instructions, types of readings, and contexts for learning influence these metacognitive behaviors. This most recent round extends previous iterations by looking at explicit instruction, in the context of GRR, aimed at improving metacognition.

3.1. Previous Iterations

At the outset of this research, Nance (Author 2) and Brittany (Author 4) wondered whether collaborative annotation of assigned texts might encourage community in an online asynchronous graduate course (Adams & Wilson, 2020). That initial inquiry yielded thousands of units of data that ultimately shed light on the comprehension strategies graduate students employed while reading academic texts: almost exclusively making personal connections (Adams & Wilson, 2022; Adams et al., 2023; Wilson et al., 2024). This finding is in response to our definition of comprehension and the metacognitive reader as stated by Pearson (2004) that reading comprehension is a complex process that occurs in the head and thus has always been difficult to see. The metacognitive reader “sizes up the potential influence of relevant factors in the reading environment (particular attributes of the text, the situation, which can be construed to include other learners, and the self) and then selects, from among a healthy repertoire of strategies that enable and repair comprehension, exactly that strategy or set of strategies that will maximize comprehension of the text at hand” (Pearson, 2004, p. 14). Because strategic readers select from multiple strategies instead of relying heavily on one, we sought to support our students in developing the “healthy repertoire” of strategies (Pearson, 2004). In response to this finding, all subsequent iterations of this research have sought to design instructional practices that better support graduate students in reading online metacognitively. Throughout, Perusall has functioned as a tool for both capturing in-process reading behaviors and scaffolding metacognitive practice.

The earliest iterations of this research were conducted within a single program at an institution in the northeastern United States. In another round, Nance and Brittany modified their instructional plan to explicitly present students with additional strategic practices that could support their reading (e.g., asking questions, summarizing, synthesizing), but doing so had little impact on their behavior (Adams & Wilson, 2022). To determine whether this was merely a feature of their program or university, they brought on additional researchers at other universities. Two additional iterations sought to determine whether the findings of prior work would hold true at other institutions, in other programs, in other parts of the country. That data confirmed that text-to-self connections are still the dominant comprehension strategy utilized by students in graduate programs, even when we controlled for assigned reading content, provided rubrics, and gave cyclical feedback (Wilson et al., 2024).

This recurring pattern has led us to consider: while our graduate students do appear to be approaching assigned readings with intention, is the assumption that these students are already strategic readers incorrect (Almasi & Fullerton, 2012)? The consistency of these results across five rounds of implementation suggests that they need additional instruction and scaffolding to be more metacognitive, strategic readers of academic texts—at least when reading these texts online. Research indicates that online and offline reading differs (Neugebauer et al., 2022), though this research is usually focused on non-linear online texts while our participants were reading linear text.

3.2. The Learning Design

In previous rounds of this research, we focused on developing a community of learners through social annotation, the types of readings presented to students, instruction on the technological tool (Perusall) utilized for social annotation and developing instruction on metacognitive reading behaviors. In this iteration, we modified the learning design by adopting a GRR framework that included explicit instruction, modeling, guided practice, independent practice, and reflection. While our team is comprised of literacy scholars, this framework is applicable across domains (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983). Adopting a modified GRR framework appropriate for asynchronous learning and focused on metacognition involved scripting explicit definitions of comprehension strategies and modeling their application in social annotation. We also were challenged to develop a mechanism for engaging in shared practice between teachers and students in asynchronous learning contexts, prior to inviting independent application by students.

Two members of the research team, Nance and Elizabeth (Author 1), volunteered to use their classes as research sites for this round. Nance taught at a medium sized comprehensive college in the northeast United States. The course in which she implemented this learning design was focused on digital literacies. Elizabeth taught at a small private university in the northeast United States. The course in which she implemented this learning design was focused on assessment-driven literacy instruction. Online teaching and learning experiences are shaped by the instructor’s course development and content knowledge, and the ways the instructor promotes building meaning through reading, viewing, listening, and inviting students to demonstrate understanding of course materials through speaking and writing (Chen et al., 2022; Garrison, 2007). Understanding this, Elizabeth and Nance met four times prior to the start of the semester to collaboratively plan instruction. During these meetings, they participated in a technology integration planning cycle (Hutchison & Woodward, 2014). This cycle includes identifying instructional goals, considering the best approaches with digital technology, taking up appropriate tools to support instruction, considering the constraints of using such tools, imagining how instruction will be delivered with these tools, and then reflecting on the instructional tool’s efficacy and potential changes in future instruction.

Elizabeth and Nance collaboratively developed slideshow presentations that would support their instruction. The first presentation was titled, “Perusall for Social Annotation and Community Engagement,” and it defined social annotation, some of its benefits, and community engagement. Here Nance also introduced questioning and criticality, and Elizabeth did not. In this learning context, we refer to criticality as analyzing and evaluating the meaning of texts through a lens of equity, power, and privilege (Adams et al., 2022). The second was titled, “Getting the Most Out of Your Course Readings,” and it defined reading comprehension, comprehension strategies, metacognition, with emphasis on monitoring and summarizing. The third was titled, “Getting the Most Out of Your Monitoring: Using Strategies to Better Comprehend.” It defined connecting, inference, and synthesizing. Elizabeth created a fourth presentation, “Using Your Metacognition to be Critically Literate,” in which she recalled metacognition, and introduced questioning and criticality, as Nance did in her first slideshow. They planned to present the slideshow presentations within a GRR framework. Notably, the slideshows’ topics also built on one another and were increasingly complex in terms of comprehension strategy use, which aligns with historical conceptions of GRR (Pearson et al., 2019). The presentations contained largely the same content, but varied slightly regarding when and in what order content was presented to learners. The instructors recorded videos of themselves talking through the presentation slides. Each video included explicit instruction, modeling, and guided practice. The videos were embedded in the courses and assigned to students in each course to complete as part of the course requirements.

As noted above, Elizabeth and Nance also used planning meetings to identify and discuss differences in their planned approaches. For example, Nance chose to record three instructional videos, shared with her students during weeks one, three, and six of the semester. She also assigned quizzes for students to complete after viewing the videos. Elizabeth chose to record an additional instructional video, assigned in week two, and did not assign quizzes. In her videos, Nance provided example annotations from prior semesters, while Elizabeth generated annotations for the texts her students would be reading. In the spirit of DBR, the study was conducted in real-world settings with multiple variables at play (Barab & Squire, 2004). While much of the learning design was determined in advance based on the five previous iterations (e.g., Adams & Wilson, 2020, 2022; Adams et al., 2022, 2023; Wilson et al., 2024), the instructors modified their individual videos to meet the needs of their students and course content.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Data collected for analysis of instructional moves included memos of research meetings in which the team revised the learning design, notes from Elizabeth and Nance’s meetings, the three slideshow presentations collaboratively developed to support the learning design, and seven instructional videos recorded by Elizabeth and Nance. The first round of analysis involved open coding (Saldaña, 2016) and analytic memoing across all data sources. The first four authors split into pairs to independently code, identifying specific instructional moves in the videos that Elizabeth and Nance used to guide student understanding (Frey & Fisher, 2010). The instructors did not code their own data. Open coding was used to assemble a preliminary codebook that captured all instructional moves used. We then brought the rest of the research team in to review codes and corroborate interpretations. When we disagreed on the code for a specific instructor move, we negotiated and clarified our understanding. Through discussion, intercoder convergence was resolved to 100%.

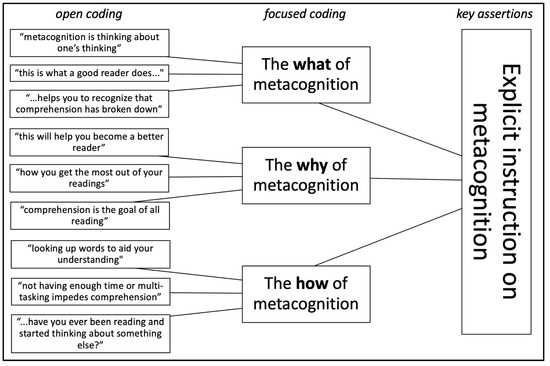

Second-round coding, focused coding (Saldaña, 2016), was used to categorize our codes into frequent instructional moves or content matter. Categories developed following corroboration included items such as “the what of metacognition,” “thinking aloud,” and “guiding questions or prompts.” Third-round coding involved establishing key assertions (Erickson, 1986) by matching focused codes with stages of GRR and triangulating across data sources (see Figure 2 for a representation of collapsing codes). We also held member checks with Elizabeth and Nance to validate or question our assumptions and understandings (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Figure 2.

Representation of collapsing codes during analysis.

4. Results

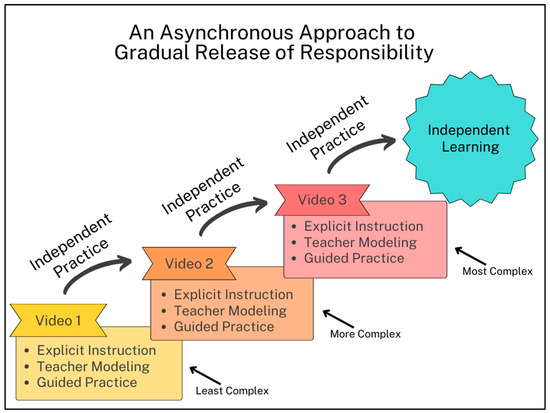

In the section below, we provide rich descriptions of the instructional moves made by Elizabeth and Nance in their online asynchronous classes. We organized the findings according to the steps of GRR: explicit instruction, modeling, guided practice, independent practice, and reflection. Because GRR is a recursive, fluid framework (Fisher, 2008; Grant et al., 2012; Pearson et al., 2019), the examples we highlight below cut across the seven recorded instructional videos grounded in the three slideshow presentations on metacognition and comprehension. While the instructional videos progressed linearly through increasingly complex metacognitive practices (e.g., making connections, questioning, synthesizing), the findings below toggle back and forth between them to explicate the steps of GRR. Our conception of the practices illuminated in this study are captured in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

An asynchronous approach to GRR.

4.1. Explicit Instruction

In the first phase of the GRR framework, the teacher provides explicit instruction to help students be able to work on the objective independently later (Durkin, 1978). While the educator explains, demonstrates, and provides a rationale, the role of the students is to be active listeners. Knowing that “before students can be expected to produce independently, they need to understand the purpose and experience an example,” Elizabeth set the stage in her first video by explaining how students would complete the Perusall assignments, why Perusall was being used as a platform, and explicitly stated her intentions and expectations for the assignments (Fisher & Frey, 2008b, p. 41). Nance also began her first video by setting expectations, connecting to information from previous courses, and explicitly stating that comprehension is the goal of all the reading tasks assigned in her course.

Throughout both Elizabeth and Nance’s videos, they continued to reinforce expectations and elaborate on definitions while drawing upon previously taught information. Students were reminded about what was taught in earlier videos and new information was layered on to demonstrate different metacognitive strategies and what they look like in practice. For example, Elizabeth asked,

Have you ever been reading and started thinking about what you were going to make for dinner? Suddenly you realize you have no idea what the last half page of text said because you were distracted by thoughts of dinner. That is when being metacognitive about your reading helps you to recognize that comprehension has broken down.

Both instructors were also careful to provide concrete examples and explanations, such as “Monitoring behaviors might include looking up words to aid your understanding. It might include restating the text or asking questions regarding your practice.” Additionally, Nance addressed things that can get in the way of comprehension, such as not having enough time or multi-tasking, and warned students that these challenges can impede comprehension.

When explaining how the annotation assignments are designed to maximize understanding, Elizabeth operated from the assumption that her students care and want to do well. This is evident by her commenting, “this is how you get the most out of it” when addressing the annotation process. Nance operated from a similar assumption by telling her students that the assignments were “to help you become a better reader.” This type of stance can increase student effort and, ultimately, achievement (Fisher & Frey, 2008a).

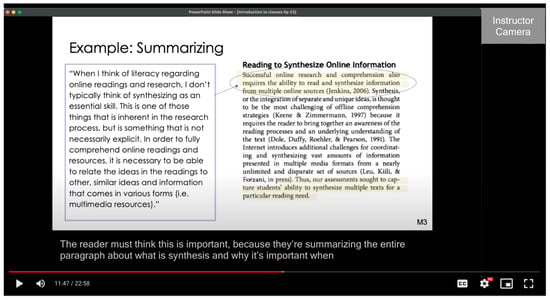

Nance used articles her students would read later in the semester to highlight examples of student annotations and demonstrate how she, the instructor, might interpret the comments. Nance used explicit language like “The reader must think this is important, because…” and “A good reader makes sure to…” (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Explicit instruction provided by Nance.

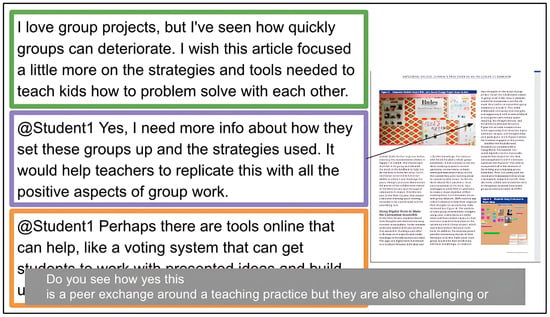

Similarly, Elizabeth displayed example student comments from Perusall in her video and explained how the students were building community by discussing a teaching practice and simultaneously questioning the text (Figure 5). Elizabeth continued to provide context and examples, digging deeper into what was expected when summarizing and monitoring. Nance also provided in-depth examples of monitoring and summarizing, while unpacking each.

Figure 5.

Explicit Instruction provided by Elizabeth.

4.2. Modeling

With the purpose set and examples given, Elizabeth and Nance moved into the modeling phase. In this phase, the instructor transitions beyond merely telling students about strategies and skills, by providing a step-by-step demonstration that closely mirrors what will be asked of the students later. Both Elizabeth and Nance used a mode of instruction known for improving comprehension and promoting social interaction called a think-aloud (N. Duke & Pearson, 2002; Kucan & Beck, 1997). “Teacher think-aloud is typically conceived of as a form of teacher modeling” (N. Duke & Pearson, 2002, p. 214). In this mode, the teacher, an expert reader, verbalizes their thinking during reading to overtly demonstrate effective comprehension strategy use.

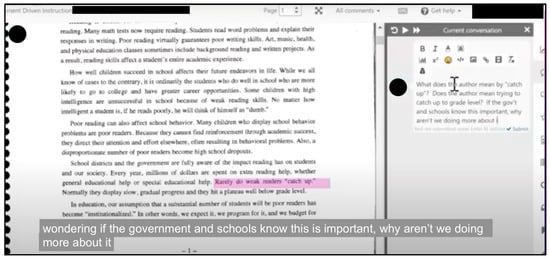

Elizabeth began by walking through exactly how to find Perusall on the course management system through the student view. She clicked on a module and hovered her mouse over the readings, emphasizing that there was an external learning tool icon for Perusall so students could easily navigate to the site. She clicked the Perusall link and showed students how Perusall opens, how they could access the readings, and how they could begin annotating (Figure 6). Elizabeth verbalized her thinking as she read aloud a snippet of a text (Kilpatrick, 2016, p. 1), stating,

Figure 6.

Elizabeth modeling using Perusall.

Here I am on page one of a text you will read in an upcoming week, and I want to model for you how I might monitor my thinking. So, in the second to last paragraph it says, “School districts and the government are fully aware of the impact reading has on our students and our society. Every year, millions of dollars are spent on extra reading help, whether general education help or special education help. Rarely do weak readers ‘catch up.’ Normally they display slow, gradual progress and they hit a plateau well below grade level.” So, I am going to highlight this [“Rarely do weak readers ‘catch up.’”], and I have a question I want to ask as I’m monitoring: What does the author mean by putting “catch up” in quotes? I might start to think about the next sentence and think, “well normally they display slow gradual progress and they hit a plateau well below grade level, so does the author mean trying to catch up to grade level?” And then I’m wondering, “if the government and schools know this is important, why aren’t we doing more about it?” So, I have a couple of questions as I am monitoring my understanding of what I am reading that I would write in my annotation.

Elizabeth’s modeling was layered. First she literally modeled for students how to access the technology tool, Perusall. Then she modeled asking questions as a strategy for monitoring her own thinking. She continued reading to draw on the text to further her understanding. Finally, she asked a critical question, challenging the systems that oversee K-12 public schools.

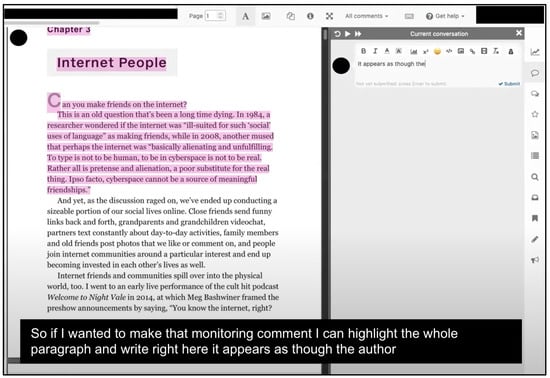

Nance similarly navigated to Perusall from her institution’s learning management system. Once she had the students’ first assigned reading open, she then posed the question, “So how do I annotate?” While thinking aloud, she demonstrated how she was able highlight a word, sentence, or paragraph. Nance highlighted the first paragraph and began to type in the text box, “It appears as though the author is starting with the argument that you can’t make friends online” (Figure 7). She then reiterated how she highlighted the passage, typed her comment, and hit submit.

Figure 7.

Nance modeling using Perusall.

Nance models how to literally use Perusall by highlighting text to add a comment, and at the same time, she modeled monitoring her own understanding. She said, “I am going to give you another example of monitoring,” and then she read the paragraph she highlighted. (See Figure 7.) Next, Nance modeled her thinking aloud:

In this first paragraph, I am getting the sense that there have been people for a long time who equate being online with being alone, and that we cannot make friends while reading online.

Nance then invited students to pause the video, read the next paragraph, monitor their own understanding, and share their response (or thinking) via the provided quiz questions as they moved into guided practice. Later, demonstrating the recursive nature of GRR, Nance then cycled back to some annotation examples from past students and repeated some explicit instruction described in the above section.

4.3. Guided Practice

During the guided practice phase of GRR, the teacher facilitates students’ first attempt to replicate the teacher’s model. This phase can be teacher- or student-led as appropriate. The objective is to provide a space for students to try their hand at the skill or strategy being taught in a highly supported environment. Asynchronous learning contexts present a unique challenge for this phase.

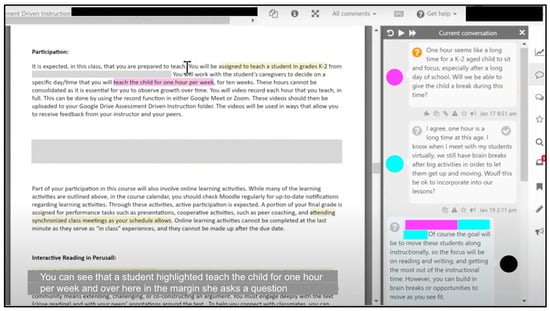

Elizabeth addressed this by giving her students an easy text to practice their annotation: the course syllabus. In the first video, she first reviewed strategies for establishing collaborative, community sense-making. Readers stay engaged while reading by asking questions or contributing to a peer’s thinking by responding to questions or challenging another’s thoughts or comments. She opened the course syllabus in Perusall and again modeled annotating the text herself (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Elizabeth using the course syllabus as guided practice.

After this, Elizabeth invited students to participate: “You can pause this video and think about a place in the text where you could stop and monitor your own understanding…I’m trying to release responsibility to you so you can try it yourself on a low stakes text.”

Nance also addressed the guided practice phase by displaying her students’ assigned chapter (McCluhan, 1964), and building pauses into the video for students to practice with the video guiding them. At one point, she said,

Remember, don’t be afraid to ask questions. It’s your job as a critical reader to challenge the text, print, video, or image. We are going to take some time to practice on this text. You can see that I scrolled down to the second paragraph. I want you to read the second paragraph and start thinking about the questions that I posed on the previous slide. Who wrote this? Why do you think McCluhan wrote the paragraph in this way? Who is the intended audience of this paragraph? Who is the article about? Who is he talking about in the article? Are there perspectives that are missing? Again, you’re just reading a paragraph, so you might not be able to answer every question. That’s okay. How are they writing about this subject? What language are they using as they talk about the medium? And again, don’t be afraid to challenge the text.

Throughout the video and multiple pauses, Nance continued to offer statements of encouragement, guiding students regarding the assigned task to read with a critical eye, and she provided additional think-alouds and models for students.

Additionally, Nance designed quizzes for each of her videos that students were required to complete after viewing sections of the video to improve accountability and provide opportunities to practice the skill. The questions were designed to prompt students to think about their own thinking, reflect on their understanding of the video content, and ultimately walk away with useful summative notes (see Table 1 for example questions).

Table 1.

Example Quiz Questions in Nance’s Course.

4.4. Independent Practice

After guided practice, Elizabeth and Nance encouraged students to independently practice metacognition and reading comprehension strategies. Independent practice is the most hands-off phase in terms of instructor involvement, making it harder to capture when analyzing teaching videos. However, the research team noticed some consistent moves made by both instructors to set students up for successfully entering this phase. Both Elizabeth and Nance made connections to theory. For instance, they both made reference to Rosenblatt’s (1994) reader-response theory. Nance reminded students that Perusall is a tool for making transactions with the text visible to their peers and instructor. As another example, Elizabeth made reference to the social learning theory, saying, “I am thinking about how we are using Perusall. We’re really thinking about reading through a constructivist lens. We can help each other. We can build on each other’s understanding with this tool.”

Both instructors also offered questions as invitations to participate. Videos always included questions like, “How will you demonstrate your metacognition in this class?” and “How are you going to practice summarizing as you go into your reading today?” Nance also made statements like, “I’d like to hear your connections, too,” after she modeled making a connection to the text. They repeatedly reminded students that it is acceptable, expected even, to challenge the text. Elizabeth acknowledged students’ possible hesitancy to push back on a text assigned by their instructor, saying

Don’t be afraid to ask questions. It’s your job to challenge the text. I know that’s funny coming from a professor saying, ‘Here’s a text I want you to read. I think it’s really valuable and important.’ But I want you to be critical consumers of anything you encounter, including the things I give you…I hope this helps you to be a more thoughtful consumer as you are reading, whatever you might read, in the classes you encounter.

4.5. Reflection

Pearson et al. (2019) recently identified reflection as an essential fifth phase of GRR, for both teachers and students. To that end, each instructor maintained journals throughout their implementation of the GRR framework. Both Nance and Elizabeth wrote reflective memos during their meetings and after each video was recorded. These memos documented their joint and separate instructional decisions, as well as ideas for what they might do differently in the next iteration. For example, Elizabeth wrote about her decision to emphasize community interaction in her first video,

I decided to start with introducing Perusall and its benefits, as well as how we can engage as a community with it in lieu of a discussion board. Given that my students’ first assignment is to annotate the syllabus, I want them to push themselves to engage with one another first.

Elizabeth understood annotating the syllabus as low-stakes practice as it doesn’t demand much in the way of metacognitive reading practices. It is also related to ease of entry and scaffolding, a fundamental teaching move at the core of GRR (Pearson et al., 2019), as well as building community, first, so that students are comfortable sharing their thinking in front of their peers.

Nance documented her instructional decision to include a quiz for each video so that students would “engage actively with the teaching videos and reflect on their understanding.” Her memos indicate that students did well on the quizzes. Drawing on data from the quizzes and anecdotal feedback from students Nance wrote, “In the future I think I need to do more modeling.” She also documented the unexpected that occurs when teaching. In one memo she noted,

My recording about synthesis got cut off and I didn’t realize this until I made the quiz. However, this means the quiz ended with students doing a little bit of hands-on practice, so I think it is okay. I may make a quick two-minute video on synthesis for next week. And that might end up being better for the GRR process.

The instructors reported that the planned reflection helped them to think about their instructional moves and how they might do things differently going ahead. Anecdotally, the instructors shared that the students seemed more engaged in this iteration of our ongoing research. The research team also felt that the iterative nature of this design-based study was greatly enhanced by structured reflection.

5. Discussion and Implications

At the onset of this study, we found ourselves in a similar position as Durkin (1978). Previous iterations of this DBR revealed that graduate students approached academic reading with intention but were mostly limited to making text-to-self connections (Adams et al., 2022, 2023; Wilson et al., 2024). This pattern caused us to challenge our assumption that graduate students come to texts in our online classes as strategic readers (Almasi & Fullerton, 2012) and prompted us to design explicit instruction and scaffolding to support students as metacognitive readers of digital, academic texts in online contexts. We recognize metacognition as a characteristic of active learners and vital for higher order thinking and understanding of complex texts, a goal we have for our own students (Conley & French, 2014; Mokhtari & Reichard, 2002; Ward & Butler, 2019; Young & Fry, 2008; Veine et al., 2020). We also understand that reading an online text differs from a traditional hard copy, which works left to right, and chapter by chapter, page by page. Digital texts are increasingly multimodal; readers may visit a number of hyperlinks, sometimes reading out of order (Coiro, 2003).

Given our backgrounds in literacy and expertise in comprehension, we drew on the findings of Durkin (1978) and the GRR framework (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983), to design instruction within a GRR model for online, asynchronous classes to instruct and scaffold our students’ reading of digital, academic texts. It seemed like a fitting framework to guide and build our students’ metacognition and comprehension. For us, this is especially important as we expect that our students, when teachers, will take up this framework with their own students.

Our goal of this paper was to provide a rich description of GRR in an online context so it could be taken up or applied by instructors across domains. There are myriad other best practices when it comes to online teaching (e.g., Martin et al., 2023; Thomas et al., 2017) but have yet to have taken up the GRR framework explicitly. We hope instructors can see themselves in our descriptions or think of ways they can enhance their own online instruction and students’ learning with the GRR framework. This matters because instructors across a variety of disciplines may wish to utilize a framework that allows for explicit instruction, modeling, shared practice, and leads to individual application. While our instructional approaches were embedded in literacy education courses, we believe that instructors and students in all fields would benefit from an instructional framework that emphasizes the shift in responsibility to ensure students develop the skill sets they need to succeed.

While the organization of this paper presents the steps of GRR in a linear order, we also made an effort to underscore its recursive nature to clarify that instructors may move back and forth between the phases based on students’ understanding (Fisher, 2008; Grant et al., 2012). Instructors must think of GRR as a flexible framework. For example, if an instructor is teaching from a constructivist lens in a unit of inquiry, they may have the students participate in independent or guided practice before providing explicit instruction or modeling (Pearson et al., 2019). Similarly, the progression and duration between the steps may look different for students as some may need more modeling or guided practice. This is where reflection seems to be an important part of the framework, as reflection invites instructors to examine the efficacy of their own teaching as well as to monitor students’ progress.

6. Conclusions

The goal of this paper was to provide rich descriptions of our use of the GRR framework in online, asynchronous courses to instruct and scaffold graduate students reading of digital, academic texts. We provided, anecdotally, our insights: students seemed most engaged in this iteration. However, we will not know the efficacy of our instructional efforts until we examine students’ annotations for evidence of comprehension strategies. Our next step is to examine the quality and depth of their metacognitive strategy used within the annotations, given explicit instruction, modeling, and guided practice in this iteration. Future research should continue to examine how we can best teach and assess metacognition during online reading as well as students’ perceptions of implementation of such instruction. This may include surveys and/or following graduate students into the field to see if/how they apply the GRR framework in their own teaching about metacognitive strategies.

We aspire for this research to encourage other online instructors to consider the ways they provide explicit instruction, modeling, guided practice, independent practice, and reflection in their teaching. We hope our rich descriptions offer a turnkey model for implementing GRR across domains and contexts. As always, regardless of modality, the goal is always student learning and understanding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.S.W., E.Y.S. and J.B.; methodology: N.S.W., E.Y.S., J.B., T.M.D. and B.A.; software: N.S.W. and E.Y.S.; validation: N.S.W., E.Y.S., J.B., T.M.D., B.A. and L.S.; formal analysis: N.S.W., E.Y.S., J.B., T.M.D. and B.A.; investigation: N.S.W., E.Y.S., J.B., T.M.D. and B.A.; resources: N.S.W., E.Y.S., J.B., T.M.D. and B.A.; data curation: N.S.W. and E.Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation: N.S.W., E.Y.S., J.B., T.M.D. and B.A.; writing—review and editing: N.S.W., E.Y.S., J.B., T.M.D., B.A., L.S. and J.B.-F.; supervision: N.S.W. and E.Y.S.; project administration: N.S.W. and E.Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board of SUNY Cortland, Code Approval 171858, Date Approval 4 January 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent was obtained by all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to student privacy best practices.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Ackerman, R., & Goldsmith, M. (2011). Metacognitive regulation of text learning: On screen versus on paper. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17(1), 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerman, R., & Lauterman, T. (2012). Taking reading comprehension exams on screen or on paper? A metacognitive analysis of learning texts under time pressure. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1816–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B., Dussling, T., Stevens, E., & Wilson, N. S. (2022). Troubling critical literacy assessment: Criticality-in-process. Journal of Literacy Innovation, 7, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, B., & Wilson, N. S. (2020). Building community in asynchronous online higher education courses through collaborative annotation. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(2), 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B., & Wilson, N. S. (2022). Investigating students’ during-reading practices through social annotation. Literacy Research and Instruction, 61(4), 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B., Wilson, N. S., Dussling, T., Stevens, E. Y., Van Wig, A., Baumann, J., Yang, S., Mertens, G. E., Bean-Folkes, J., & Smetana, L. (2023). Literacy’s Schrödinger’s cat: Capturing reading comprehension with social annotation. Teaching Education, 34(4), 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasi, J. F., & Fullerton, S. K. (2012). Teaching strategic processes in reading (2nd ed.). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Barab, S., & Squire, K. (2004). Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, J. F., & Schmitt, M. C. (1986). The what, why, how, and when of comprehension instruction. The Reading Teacher, 39(7), 640–646. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R., Pressley, M., Van Meter, P., & Schuder, T. (1995). A quasi-experimental validation of transactional strategies instruction with previously low-achieving, second-grade readers. Reading Research Report No. 33. National Reading Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X., Yang, S., Karkar Esperat, T., Bahlmann Bollinger, C. M., Van Wig, A., Wilson, N. S., & Pole, K. (2022). Literacy faculty perspectives during covid: What did we learn? Literacy Practice and Research, 47(2), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, M. M. (2008). Flowing toward correct contributions during group problem solving: A statistical discourse analysis. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 17(3), 415–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M. M., & Kuo, S. W. (2010). From metacognition to social metacognition: Similarities, differences and learning. Journal of Education Research, 3(4), 321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Clinton-Lisell, V., Seipel, B., Gilpin, S., & Litzinger, C. (2023). Interactive features of E-texts’ effects on learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(6), 3728–3743. Available online: https://doi-org.utk.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/10494820.2021.1943453 (accessed on 1 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Coiro, J. (2003). Exploring literacy on the internet. The Reading Teacher, 56(4), 458–464. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, D. T., & French, E. M. (2014). Student ownership of learning as a key component of college readiness. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(8), 1018–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D. S., & Neitzel, C. (2012). Collaborative sense-making in print and digital text environments. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 25(4), 831–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, N., & Pearson, P. D. (2002). Effective practices for developing reading comprehension. In A. E. Farstrup, & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp. 205–242). International Reading Association. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, N. K., Pearson, P. D., Strachan, S. L., & Billman, A. K. (2011). Essential elements of fostering and teaching reading comprehension. In S. J. Samuels, & A. E. Farstrup (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (4th ed., pp. 51–93). International Reading Association. [Google Scholar]

- Durkin, D. (1978). What classroom observations reveal about reading comprehension instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 14, 481–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, F. (1986). Qualitative methods in research on teaching. In M. Wittrockk (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 119–161). MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D. (2008). Effective use of the gradual release of responsibility model. Macmillan. Available online: http://srhscollaborationsuite.weebly.com/uploads/3/8/4/0/38407301/douglas_fisher.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2008a). From better learning through structured teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2008b). Homework and the gradual release of responsibility: Making “responsibility” possible. English Journal, 98, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J. H. (1993). Cognitive development (3rd ed.). Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2010). Identifying instructional moves during guided learning. The Reading Teacher, 64(2), 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S., & Palmer, J. (2020). The pandemic pushed universities online. The change was long overdue. Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/09/the-pandemic-pushed-universities-online-the-change-was-long-overdue#:~:text=Following%20a%20slow%2C%20two%2Ddecade,learning%20experiences%20and%20business%20models (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Gao, F. (2013). Case study of using a social annotation tool to support collaboratively learning. Visual Communications and Technology Education, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, I., Xu, Z., & Hardaker, G. (2007). Online annotation—Research and practices. Computers & Education, 49(4), 1308–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, A. P., Cho, S.-J., Reynolds, D., Brady, K., & Salas, J. (2020). Digital versus paper reading processes and links to comprehension for middle school students. American Educational Research Journal, 57(4), 1837–1867. Available online: https://doi-org.utk.idm.oclc.org/10.3102/0002831219890300 (accessed on 1 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Grant, M., Lapp, D., Fisher, D., Johnson, K., & Frey, N. (2012). Purposeful instruction: Mixing up the “I,” “we,” and “you”. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56(1), 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravemeijer, K., & Cobb, P. (2006). Design research from a learning design perspective. In J. van den Akker, K. Gravemeijer, S. McKenney, & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational design research (pp. 17–51). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, R., Spickler, D., Bergner, J., & Bardzell, M. (2009). A qualitative approach to assessing technological pedagogical content knowledge. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 9(4), 392–411. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, A., & Woodward, L. (2014). A planning cycle for integrating digital technology into literacy instruction. The Reading Teacher, 67(6), 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y. C. (2022). Reading in print versus digital media uses different cognitive strategies: Evidence from eye movements during science-text reading. Reading and Writing, 35(7), 1549–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Ma, L., & Gao, L. (2016). Assessing teachers’ metacognition in teaching: The teacher metacognition inventory. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. E., Archibald, T. N., & Tenenbaum, G. (2010). Individual and team annotation effects on students’ reading comprehension, critical thinking, and meta-cognitive skills. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalir, J. H., Morales, E., Fleerackers, A., & Alperin, J. P. (2020). “When I saw my peers annotating”: Student perceptions of social annotation for learning in multiple courses. Information and Learning Sciences, 121(3/4), 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: Do students practise retrieval when they study on their own? Memory, 17(4), 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendeou, P., van den Broek, P., Helder, A., & Karlsson, J. (2014). A cognitive view of reading comprehension: Implications for reading difficulties. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 29(1), 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, D. A. (2016). Equipped for reading success: A comprehensive, step-by-step program for developing phonemic awareness and fluent word recognition. Casey & Kirsch Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kintsch, W. (2013). Revisiting the construction-integration model of text comprehension and its implications for instruction. In D. E. Alvermann, N. J. Unrau, & R. B. Ruddell (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (6th ed., pp. 807–839). International Reading Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, K. Y., & Ho, I. T. (2010). Metacognitive strategies that enhance critical thinking. Metacognition and Learning, 5(3), 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucan, L., & Beck, I. L. (1997). Thinking aloud and reading comprehension research: Inquiry, instruction, and social interaction. Review of Educational Research, 67(3), 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. (2005). Reading behavior in the digital environment: Changes in reading behavior over the past ten years. Journal of Documentation, 61(6), 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F., Kumar, S., Ritzhaupt, A. D., & Polly, D. (2023). Bichronous online learning: Award-winning online instructor practices of blending asynchronous and synchronous online modalities. The Internet and Higher Education, 56, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, K. A. (2010). A review of the “digital turn” in the New Literacy Studies. Review of Educational Research, 80(2), 246–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, K., & Reichard, C. A. (2002). Assessing students’ metacognitive awareness of reading strategies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, E., Kalir, J. H., Fleerackers, A., & Alperin, J. P. (2022). Using social annotation to construct knowledge with others: A case study across undergraduate courses. F1000 Research, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). Use of educational technology for instruction in public schools: 2019–2020. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2021/2021017Summary.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Neugebauer, S. R., Han, I., Fujimoto, K. A., & Ellis, E. (2022). Using national data to explore online and offline reading comprehension processes. Reading Research Quarterly, 57(3), 1021–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, P. D. (2004). The reading wars. Educational Policy, 18(1), 216–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, P. D., & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8(3), 317–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, P. D., McVee, M. B., & Shanahan, L. E. (2019). In the beginning: The historical and conceptual genesis of the gradual release of responsibility. In M. B. McVee, E. Ortlieb, J. S. Reichenberg, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), The gradual release of responsibility in literacy research and practice (pp. 1–21). Emerald Group Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Reinking, D., & Bradley, B. A. (2008). Formative and design experiments: Approaches to language and literacy research. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reutzel, D. R., Smith, J. A., & Fawson, P. C. (2005). An evaluation of two approaches for teaching reading comprehension strategies in the primary years using science information texts. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20, 276–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, L. M. (1994). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In R. B. Ruddell, M. R. Ruddell, & H. Singer (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (4th ed., pp. 1057–1092). International Reading Association. [Google Scholar]

- Sage, K., Augustine, H., Shand, H., Bakner, K., & Rayne, S. (2019). Reading from print, computer, and tablet: Equivalent learning in the digital age. Education and Information Technologies, 24(4), 2477–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe, A., Lind, F., Kosch, L., & Boomgaarden, H. G. (2022). No negative effects of reading on screen on comprehension of narrative texts compared to print: A meta-analysis. Media Psychology, 25(6), 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, J. E., Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2018). Grade increase: Tracking distance education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y., & Gao, F. (2017). Comparing the use of a social annotation tool and a threaded discussion forum to support online discussions. The Internet and Higher Education, 32, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. A., West, R. E., & Borup, J. (2017). An analysis of instructor social presence in online text and asynchronous video feedback comments. Internet and Higher Education, 33, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K. H., Hicks, T., & Zucker, L. (2020). Connected reading: A framework for understanding how adolescents encounter, evaluate, and engage with texts in the digital age. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(2), 291–309. Available online: https://doi-org.utk.idm.oclc.org/10.1002/rrq.271 (accessed on 1 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Veine, S., Anderson, M. K., Andersen, N. H., Espenes, T. C., Søyland, T. B., Wallin, P., & Reams, J. (2020). Reflection as a core student learning activity in higher education: Insights from nearly two decades of academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(2), 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R. T., & Butler, D. L. (2019). An investigation of metacognitive awareness and academic performance in college freshmen. Education, 139(3), 120–126. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, S., Massey, D., Goggans, M., & Flajole, K. (2019). Thirty-five years of the gradual release of responsibility: Scaffolding toward complex and responsive teaching. The Reading Teacher, 73(1), 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N. S., Dussling, T., Adams, B., Stevens, E., Baumann, J., Yang, S., Smetana, L., Bean-Folkes, J., & Van Wig, A. (2024). What a multi-institutional collective case study of social annotation data reveals about graduate students’ metacognitive reading practices. Literacy, 58(2), 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A., & Fry, J. D. (2008). Metacognitive awareness and academic achievement in college students. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 8(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar, A., & Lustov, E. (2018). Challenges in addressing metacognition in professional development programs in the context of instruction of higher-order thinking. In W. Yehudith, & L. Zipora (Eds.), Contemporary pedagogies in teacher education and development (Chp. 6). IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).