Abstract

Based on flipped learning, digital competence, and inclusive instructional design, this study employs a mixed-method approach (quantitative and qualitative) to evaluate the pilot and involves academics from six European universities. Teacher participants co-designed and implemented flexible learning scenarios using the FLeD tool, which integrates pedagogical patterns, scaffolding strategies, and playful features. Using a mixed-methods research approach, this study collected and analyzed data from 34 teachers and indirectly over 800 students. Results revealed enhanced student engagement, self-regulated learning, and pedagogical innovation. While educators reported increased awareness of inclusive teaching and benefited from collaborative design, challenges related to tool usability, time constraints, and the implementation of inclusivity also emerged. The findings support the effectiveness of structured digital tools in promoting pedagogical transformation in online, face-to-face, and hybrid learning. This study contributes to the discussion on the digitalization of higher education by illustrating how research-informed design can enable educators to develop engaging and flexible inclusive learning environments in line with the evolving needs of learners and the opportunities presented by technology.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed an unprecedented transformation in higher education teaching practices, forcing a rapid transition to online and flexible teaching modalities. Faculty members have experienced an accelerated development in their digital competencies, driven by necessity rather than choice (Beardsley et al., 2021; Morgado et al., 2021). As emphasized by the European Plan for Digital Education (European Commission, 2020), this shift demanded that educators quickly develop digital competencies while maintaining effective student engagement in virtual environments.

The evolution of faculty digital competence has been marked by varying levels of adaptation and innovation. While some institutions and educators successfully transformed their teaching approaches, others struggled with digitizing traditional methods. This disparity has highlighted the critical need for systematic training in technology-mediated digital pedagogy, as supported by several studies (Låg & Sæle, 2019; Lin & Hwang, 2019; Cardoso et al., 2019; Weiß & Friege, 2021).

A significant gap remains concerning effective learning design for digital contexts across participating universities. While faculty members have developed basic digital literacy and broadened their perspective toward flexible learning forms, many still struggle to design effective learning experiences in digitally mediated environments. This gap is particularly evident in blended and hybrid learning approaches, where traditional content-based teaching methods are often merely adapted to virtual contexts rather than fundamentally redesigned (Bishop & Verleger, 2013). The EDUCAUSE Report (Pelletier et al., 2022) further supports this trend, identifying flipped learning as an expanding modality in higher education.

In a review of 70 articles based on the experience gained from pandemic practices with online flipped courses, Lo (2023) identified many challenges, such as low student participation in classes, the difficulty for teachers to observe students on screen, and the lack of tangible hands-on practice. With this analysis, they propose a RAISE design framework with five aspects: Resources (e.g., provision of instructional videos), Activities (e.g., emphasis on application of knowledge and skills), Institutional facilitation (e.g., allocation of budgets for educational technology), Support (e.g., use of tools for student response and collaboration) and Evaluation (e.g., provision of formative assessment and teacher feedback).

Clark et al. (2022) in a study on the online flipped classroom with adaptive learning, highlighted the occurrence of positive changes: perception of the classroom environment, preference for flipped instruction, perception of the responsibility imposed, motivation for independent learning, and perception of learning. The results also point to a significant decrease in the proportion of students who felt burdened, overwhelmed, or stressed in the online flipped classroom. These conclusions are in line with the recommendation for a post-pandemic education in which the adoption of adaptive learning and flipped instruction will be fundamental (medical and engineering, for example).

However, research indicates that more investigation and practice on effective technology-mediated pedagogies for flipped learning are needed (Låg & Sæle, 2019; Lin & Hwang, 2019; Weiß & Friege, 2021). This need is particularly acute in sudden shifts between teaching modalities, as experienced during the pandemic.

The need for flexible, inclusive approaches has become increasingly apparent, as emphasized by Veletsianos and Houlden (2019) in their comprehensive analysis of flexibility in education. Their research identified key themes such as “anywhere, anytime” learning and the necessity for adaptable pedagogy, incorporating flexible delivery methodologies and content. This aligns with what Noguera et al. (2022) discuss regarding flexible teaching and learning, emphasizing that it extends beyond traditional notions of flexibility to address individual learner needs. The emergence of diverse learning contexts (face-to-face, hybrid, and online) has amplified the need for flexible and inclusive teaching approaches. This need is particularly acute in addressing the challenges faced by students from disadvantaged backgrounds or those with special needs. The situation calls for adaptive frameworks that efficiently guide teachers toward flexible teaching methods while ensuring accessibility and inclusivity in higher education.

The FLeD project’s theoretical framework integrates three interconnected components: flipped learning methodology, flexible learning design, and digital competence development. The flipped classroom approach emphasizes student-centered learning through optimized asynchronous engagement and self-paced study (Bishop & Verleger, 2013; Låg & Sæle, 2019). The flexible learning design framework encompasses six dimensions: inclusivity, learning styles, task approach flexibility, independent work, interaction patterns, and multimodality options (Dikilitas & Noguera, 2023), built upon design patterns theory (Gros et al., 2016). These elements align with the core principles of learner choice, equivalency, reusability, and accessibility (Huang et al., 2020). Digital competence development, aligned with the European Digital Education Plan, emphasizes educators’ mastery of technology-mediated pedagogy (Beardsley et al., 2021; Morgado et al., 2021). This integrated framework addresses the need for effective learning in digitally mediated contexts while promoting inclusive and adaptive teaching approaches.

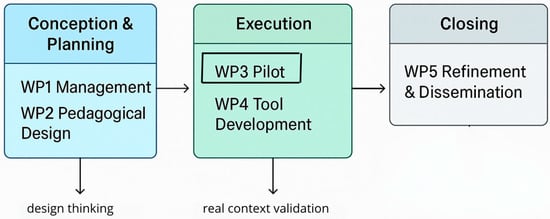

The Learning Design for Flexible Education (FLeD) project directly addresses the European Commission’s call (2022–2025 KA220-HED) for innovation in digitally supported teaching and learning. Running from December 2022 to May 2025, the project brings together six leading European institutions: Università Degli Studi di Trento, Universidade Aberta, Universitetet I Stavanger, Sofia University St Kliment Ohridski, Universidad Pompeu Fabra, and Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. The project targets a significant gap in pedagogical effectiveness in digital learning contexts. It is organized into three phases and five work packages (WPs) (cf. Figure 1) and was conceived following a design thinking approach (Brown, 2009), with a strong focus on collaborative design and user-centered innovation. While not based on a design-based research (DBR) methodology (Anderson & Shattuck, 2012), but in a mixed-methods approach, some iterative cycles were integrated in the pilot implementation (WP3)—the focus of this article—to ensure responsiveness to real-world contexts.

Figure 1.

Project phases and work packages.

The specific objectives of the pilot (WP3), as stated in the project’s proposal document are: (a) to test the pattern, scaffolding, and playful experience using the FLeD tool with real users; (b) to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the pattern, scaffolding, playful; (c) experience, and the FLeD tool to structure and support the effective application of the flipped method; (d) to refine the pattern, scaffolding, and the FLeD tool to ensure a playful experience and the development of inclusive learning scenarios.

This study investigates the pilot implementation by addressing the following research questions:

- How do university teachers perceive and engage with digital tools and pedagogical resources for designing flipped and flexible learning scenarios?

- What challenges and enablers do faculty encounter when implementing flipped learning in diverse higher education contexts?

- To what extent do the FLeD resources (patterns, scaffolds, and the FLeD Tool) support inclusive teaching practices and address student diversity?

- What impact does the FLeD pilot have on student engagement, self-regulated learning, and collaboration in flipped classroom settings?

- How does participating in the collaborative design and implementation of flipped scenarios influence teachers’ pedagogical innovation and reflection?

Following the exploratory and mixed-methods approach of this study, we have formulated hypotheses that reflect anticipated outcomes based on previous literature concerning flipped learning, inclusive instructional design, and digital pedagogy, to guide data interpretation and structure our analysis, in line with our research questions:

- H1: Teachers using the FLeD toolkit and flipped learning patterns will report positive perceptions of flexibility, inclusiveness, and support for student self-regulation in their course designs.

- H2: Faculty members will identify technical and pedagogical enablers (e.g., collaborative features and scaffolding strategies) and challenges (e.g., time constraints and tool usability) when implementing flipped learning with the FLeD toolkit.

- H3: Teachers will perceive the FLeD resources as contributing positively to the development of inclusive and accessible learning scenarios that address student diversity, though implementation challenges may remain.

- H4: The use of FLeD-supported flipped scenarios will lead to higher levels of student engagement, collaboration, and self-regulated learning, as teachers perceive it.

- H5: The participation in collaborative design and implementation will support teachers’ pedagogical innovation and reflective practice.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the conceptual and methodological basis of the FLeD framework, including its pedagogical principles and the development of the digital tool. Section 3 describes the pilot design and implementation across partner institutions. Section 4 outlines the data collection and analysis methods used to evaluate the pilot. Section 5 reports on key findings drawn from both quantitative platform data and qualitative feedback from participants. This section also discusses the implications of these findings for the design of flipped learning and faculty development. Finally, it concludes with reflections on the lessons learned and directions for future research and refinement.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Faculty Development in Digital Contexts

Flipped learning has gained popularity in recent years, particularly during the pandemic as a response to the need for online and blended modes of teaching and learning. As a result, teachers have developed digital competencies and have broadened their perspective towards flexible forms of learning (Albó et al., 2020; Noguera & Valdivia-Vizarreta, 2023).

The concept of professional digital competence is emerging as a framework for teacher preparation in the digital age (Starkey, 2019). Research in digital teacher professional development emphasizes the need for innovative, digitally enabled approaches to faculty development that can enhance teaching quality and student engagement in digital spaces (Lay et al., 2020). Institutions employ diverse professional development practices, but face challenges like culture change and unclear expectations (VanLeeuwen et al., 2020). Effective faculty development should be theory-based, rigorously evaluated, and consider individual differences and cost-effectiveness (K. A. Meyer, 2013). A systematic review reveals a lack of teacher training and insufficient ICT preparation, underscoring the need for improved digital competence development (Fernández-Batanero et al., 2022). Another study shows that university teachers have a mostly intermediate level of digital skills, independent of gender, but dependent on the generational cohort (Jorge-Vázquez et al., 2021). Basilotta-Gómez-Pablos et al. (2022) found that university teachers often self-assess their digital competencies as low or medium-low, particularly in evaluating educational practices. Overall, these studies underscore the growing importance of digital competencies in higher education and the need for targeted faculty development initiatives to enhance these skills.

Digital competence frameworks aim to improve teachers’ digital competencies and, consequently, enhance student learning in digital environments. The newly developed digital competencies for teachers in the Higher Education framework specifically address higher education teachers’ digital competencies, encompassing teaching practice, empowering students, digital literacy, and professional development (Tondeur et al., 2023). Several frameworks have been developed to guide digital competence development, including the European Digital Education Plan, which emphasizes educators’ mastery of technology-mediated pedagogy (Morgado et al., 2021); DigCompEdu, ISTE standards, and the Norwegian professional digital competence framework can be applied to initial teacher education, though they may need adaptation for student teachers’ specific needs (Starkey & Yates, 2021). Research suggests that clear conceptual frameworks can lead to effective faculty development strategies (Raffaghelli, 2017).

2.2. Flipped Learning in Higher Education

Recent research on flipped learning in higher education highlights its potential to enhance student engagement, performance, and various skills across disciplines (Al-Samarraie et al., 2020). Studies indicate an increasing trend in flipped learning research, particularly in Asia, with a focus on social sciences and computer science (González-Zamar & Abad-Segura, 2022). Flipped learning has shown positive outcomes in student performance, cognitive skills, and engagement (Birgili et al., 2021). A meta-analysis of 317 studies found significant advantages of flipped learning over traditional lecture-based instruction across various learning domains (Bredow et al., 2021). However, challenges persist in implementation, requiring strategies to address them (Baig & Yadegaridehkordi, 2023). The main issue with flipped learning is its ineffectiveness when students fail to regulate their learning, prepare before class, or collaborate properly, and when the flexibility options make them feel lost (Sein-Echaluce et al., 2024). Also, the time required for material preparation and mastery (Al-Samarraie et al., 2020), as well as students’ readiness for autonomous learning (Garcia-Ponce & Mora-Pablo, 2020). A flipped learning design without adequate guidance for self-regulated learning processes and the intensive use of digital technologies might represent a barrier to students with special needs, special circumstances, or low self-regulation or digital competencies (Sosa-Díaz et al., 2021).

Despite these challenges, flipped learning continues to demonstrate potential for enhancing student learning outcomes and adapting to the evolving educational landscape in higher education (Bredow et al., 2021). Key factors contributing to successful flipped classrooms include pedagogical aspects like guidance and teaching for understanding, as well as student participation and perception of preview materials (Sointu et al., 2023). Moreover, successful implementation requires institutional support and flexible assessments (Goedhart et al., 2019).

2.3. Flexible Learning Design Framework

Flexible learning offers opportunities for diverse student populations (Andrade & Alden-Rivers, 2019), and encompasses various modalities, including online, blended, and competency-based learning (Houlden & Veletsianos, 2021). Furthermore, several learning theories are closely related to the concept of flexible learning designs, including constructivism, social constructivism, and connectivism. These theories all prioritize learner-centeredness in design, recognizing that students are active constructors of their knowledge and meaning through both their experiences and their interactions with the environment (Brieger et al., 2020). Constructivism emphasizes the active role that students play in constructing their own understanding of the world around them (Corbett & Spinello, 2020). In a flexible learning design, this approach to learning improved learning processes, active participation, self-reflection, and professional development for educators (Dziubaniuk et al., 2023). A flexible learning design that integrates social constructivist principles (Vygotsky, 1978) could offer opportunities for students to collaborate with others, such as through group projects or online discussions.

Flexible learning enhances access to higher education, particularly for underserved students, and can be supported through course design and responsive pedagogies (Andrade & Alden-Rivers, 2019). One area where such an approach can be particularly applicable can be found in flipped learning models, in which the traditional classroom instruction is flipped, and students access course materials before class so that they can engage in active learning during class time (Poole, 2021). Students prefer flipped learning models that combine synchronous and asynchronous elements, promoting self-regulation, collaboration, and autonomous learning (Noguera et al., 2022). However, the flipped classroom is often misunderstood, and there is a need for a structured pedagogical framework to support teachers in designing effective flipped learning scenarios (Schallert et al., 2022). One way to promote this understanding is to support teachers in their self-regulated learning process (Öztürk & Çakıroğlu, 2021).

To ensure that flipped learning is inclusive and accessible to all students, it is important to structure and support inclusive flipped learning scenarios. This can be achieved through the development of a digital tool and a decision-making process that considers the needs of all students, including those with special needs and disabilities (Hwang et al., 2019). It is also important to increase awareness of flexible learning, promoting inclusiveness and providing continuous and systematic feedback and support for teachers; this can help to build a culture of innovation and creativity in flexible education, which might benefit all students and teachers (Sangiuliano Intra et al., 2023).

2.4. Tools and Resources for Learning Design

The landscape of digital tools in higher education has evolved to encompass a diverse array of platforms aimed at supporting pedagogical innovation and flexible learning. Within this landscape, learning design tools play a pivotal role by assisting educators in structuring pedagogically informed scenarios (Laurillard, 2012; Wasson & Kirschner, 2020). However, despite the proliferation of such tools, support for flipped learning (FL) approaches remains limited (Albó & Hernández-Leo, 2021). The FLeD tool contributes to filling this gap by offering a dedicated platform that integrates design patterns specifically tailored for FL, addressing common challenges such as feedback exchange, student preparation, and collaborative regulation. This focus reflects a growing demand for tools that not only digitize teaching practices but also embed evidence-based pedagogical strategies, enhancing the alignment between technological affordances and learning goals.

Learning design platforms serve as mediating systems that support educators in planning and implementing structured learning experiences. The FLeD platform exemplifies this by providing an authoring environment grounded in pedagogical patterns for flipped learning (Hernández-Leo et al., 2006; McAndrew et al., 2006). Built upon foundational infrastructures such as edCrumble (Albó & Hernández-Leo, 2021) and LdShake (Hernández-Leo et al., 2014), the tool supports a modular and community-oriented approach to design. Educators engage with the platform through an intuitive interface that includes pattern selection, design editors, and timeline-based session planners. This approach enables the creation of detailed learning sequences, promotes reflection on inclusivity and self-regulation, and facilitates resource allocation for both in-class and out-of-class activities. Importantly, the platform incorporates collaborative and open design principles by enabling educators to share, duplicate, and adapt learning scenarios, fostering a culture of pedagogical co-creation and reuse.

Effective integration of educational technologies into teaching practices requires effective scaffolding frameworks that align technological tools with pedagogical intent. The FLeD tool incorporates such a framework by embedding a scaffolding system that leverages conceptual, metacognitive, strategic, and procedural dimensions (Hannafin et al., 1999; Agostini et al., 2024). Drawing on principles of contingency, intersubjectivity, and transfer of responsibility (Belland, 2017; Pea, 2004), the tool provides adaptive guidance that considers the modality of delivery (face-to-face, blended, online), the diversity of learners, and the nature of the learning tasks. This integrated approach is grounded in the principles of design-based research (Cole et al., 2005), emphasizing iterative development grounded in real-world use cases and educator feedback. The resulting framework supports educators not only in navigating the complexities of technology integration but also in designing inclusive, student-centered learning environments that encourage active engagement and self-regulation.

The FLeD platform offers a comprehensive suite of resources designed to support educators throughout the learning design process. These include pattern descriptions with detailed educational rationales and case examples, a design editor enriched with actionable recommendations, and a scaffolding panel that prompts reflective decision-making (Albó et al., 2024). Furthermore, the toolkit section of the platform provides supplementary resources such as inclusiveness handbooks, glossaries, meta-pattern documents, and a collection of instructional videos. To enhance accessibility and ensure broader adoption across diverse educational contexts, all key resources have been translated into the official languages of the project partners: Catalan, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Bulgarian, and Norwegian. Notably, the FLeD ’playful experience’ introduces a gamified pathway to foster teacher engagement, creativity, and collaboration. This playful approach is not merely motivational but strategically aligned with the goals of professional development, encouraging experimentation and co-design of flipped scenarios in a supportive, community-driven environment (Nørgård et al., 2017).

The FLeD Learning Design Tool aims to pedagogically support teachers in designing flexible learning scenarios and making informed instructional decisions, using flipped learning (FL) patterns as the foundation for their designs, particularly within the flipped classroom model (Albó et al., 2024). This part explores how the FLeD tool integrates various pedagogical elements into the learning design scenario to support teachers in creating effective and flexible learning experiences. These elements include design description, learning outcomes, assessment strategies, inclusiveness and self-regulation, challenges and solutions, implementation experiences, calendar-based planning, and recommended actions. By incorporating these elements, the tool helps educators create structured and effective learning scenarios. It also offers scaffolded guidance (Agostini et al., 2024), enabling teachers to make informed decisions when designing student-centered, adaptable, and technology-enhanced learning activities.

Teachers begin their flexible learning design scenarios in the FLeD tool by selecting a learning pattern that best aligns with their instructional goals. These patterns offer structured guidance to address key pedagogical challenges, such as enhancing student self-regulation, facilitating constructive feedback, managing collaborative activities, or utilizing a combined pattern that integrates two or more of these challenges (Albó et al., 2024). By selecting a pattern at the outset, educators gain access to targeted recommendations and design scaffolds, enabling them to develop well-structured, flexible learning scenarios informed by research and best practices (Cole et al., 2005). Once educators select a pattern, the FLeD tool provides tailored recommendations to guide their instructional choices. With these insights, teachers can then proceed to the design editor, where they structure their learning scenarios by specifying key details such as a title, description, and target educational level. They also define the intended learning outcomes and select an appropriate assessment strategy, including formative and summative evaluations. This step ensures clarity and coherence, helping educators establish a structured instructional framework, align activities with learning goals, and develop effective assessment methods to measure student progress.

Additionally, teachers integrate inclusivity and self-regulation strategies to make learning experiences accessible and adaptable for all students (Bergamin et al., 2012). The tool provides recommendations for self-regulated learners, allowing them to customize their learning paths based on individual needs. It also offers guidance on supporting diverse learners, including those with special educational needs (SEND), and provides customizable resources to accommodate varied learning preferences and accessibility requirements. These features foster an inclusive educational environment that supports diverse student profiles. Teachers can use the tool’s integrated calendar to set start and end dates and specify the number of students involved in the learning design. The calendar-based planning feature allows them to structure in-class and out-of-class sessions within a visual timeline, ensuring a clear sequence of activities. This helps balance student workload by strategically organizing synchronous and asynchronous tasks, ensuring they are well-paced, logically structured, and aligned with instructional objectives. By facilitating progress tracking and workload distribution, the calendar feature enhances the overall coherence and effectiveness of the learning design.

Clicking on a session opens an editing interface, where teachers can define learning objectives and provide detailed task descriptions. Each task includes an edit menu with a pop-up window displaying pattern-based recommendations relevant to the selected design approach. Additionally, the system allows teachers to specify whether tasks should be completed individually or in groups, with an option to define group size. Most of the tool’s icon menus open pop-up windows where users can input the necessary details, which are automatically saved upon closing. The final two fields in the design editor header become available only after the design has been implemented in a real setting, allowing educators to document challenges encountered, solutions applied, and overall experiences. This reflective feature enables teachers to analyze and refine their designs based on practical experience, benefiting both their own instructional practice and the broader teaching community (Weller et al., 2015). By sharing their designs, educators contribute to a collaborative community repository. The tool includes a dedicated page where users can browse shared learning scenarios, enabling them to reuse, adapt, and enhance existing designs (Hernández-Leo et al., 2006). Furthermore, it provides teachers with a record of past designed scenarios, allowing them to revisit and improve their strategies for future courses, informed by lessons learned and evolving pedagogical needs.

Additionally, teachers can drag and drop resources from the left panel of the editor interface into each task. There are two types of resources: consultation resources, which are materials prepared by teachers for students to reference, and product resources, which are outputs students are expected to create while completing the task. This feature is important as it streamlines the resource management process, ensuring that instructional materials are easily accessible and aligned with the learning activities. It also enhances organization and efficiency, allowing teachers to seamlessly integrate relevant content while enabling students to engage with structured guidance and produce meaningful outputs.

Throughout the design process of a learning scenario, teachers can access a scaffolding panel located on the right side of the editor interface, which offers checklists for guidance. These checklists are organized into different tabs based on design stages or topics and serve as reflection tools to help teachers refine their designs in alignment with the selected pattern. One tab remains consistent across all patterns, providing inclusiveness recommendations that specifically address the needs of students with self-regulation difficulties, students with special needs, and disadvantaged students.

2.5. Inclusive Design Principles

The inclusive learning design principles—flexibility, accessibility, and personalization—in the FLeD pilot are based on Universal Design for Learning (A. Meyer et al., 2014), and are in line with international inclusion policies such as the Salamanca Declaration (UNESCO, 1994) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 2006). These fundamental principles (multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression) enable learners with diverse needs and preferences to access content, actively participate, and demonstrate their understanding in their own personalized and appropriate way (Rose & Meyer, 2002; A. Meyer et al., 2014). Hence, FLeD views inclusive learning design as a dynamic process that embraces diversity and a sense of belonging (UNESCO, 2020).

Recognizing that accessibility encompasses contextual, relational, and technical aspects in an integrative vision of learning and its design (Seale, 2006; Cooper, 2006), the pilot raised concerns about promoting technological accessibility (e.g., assistance tools and platform usability) and integrating it with pedagogical accessibility (e.g., inclusive teaching strategies and student-centered design), as Guglielman (2010) has proposed. This dual focus ensures that learning environments are adaptable and remove barriers, enabling equitable participation for all learners (Kelly et al., 2004; Bel & Bradburn, 2008).

The FLeD tool supports educators in embedding these principles from the outset of scenario development, fostering reflective practice and collaborative planning. These inclusive approaches prepare learners for participation in diverse societies while reinforcing institutional quality and responsiveness (Soriano et al., 2017; Martins et al., 2018).

Inclusive learning design within FLeD is a continuous and evolving process responsive to learner variability, technological change, and societal demands. It offers a structured approach to achieving the objectives of the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2021) and UN Sustainable Development Goal 4.5, which promote equitable access to quality education at all levels.

3. Methods and Materials

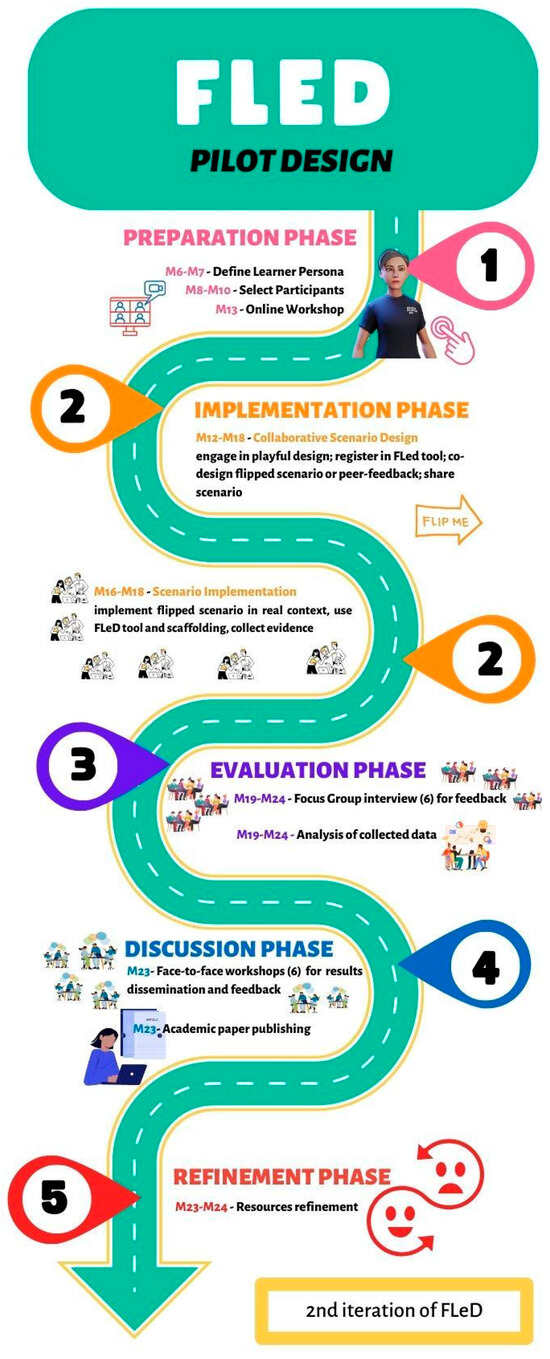

3.1. Pilot Implementation

This pilot study evaluated the efficacy and practicality of the FLeD framework and its associated digital toolkit when applied within authentic higher education contexts. The pilot implementation included two sequential phases: Collaborative Scenario Design and Flipped Scenario Implementation, each with distinct objectives and protocols (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Roadmap to FLeD pilot design. Source: Morgado et al. (2024).

In the pilots’ initial phase, ‘Phase 1: Collaborative Scenario Design’, collaborative pairs of university lecturers from the participating institutions co-created a flipped learning scenario by applying the FLeD framework and its comprehensive resource toolkit. This toolkit includes patterns, scaffolding materials, playful design elements, and the FLeDTool platform. Within these collaborative structures, a designated lecturer was primarily responsible for scenario design, while their counterpart provided formative feedback and critical reflection, thereby facilitating a recursive design process characterized by peer evaluation and iterative refinement.

Participants engaged with the provided resources and developed a series of pedagogically sound learning scenarios suitable for use in their instructional contexts. This design process encouraged the integration of innovative pedagogical approaches and appropriate digital technologies to enhance learner engagement and promote inclusive educational practices. Created learning scenarios, upon completion, were uploaded to the FLeDTool platform.

For the pilots’ next phase, entitled ‘Phase 2: Flipped Scenario Implementation’, participant lecturers operationalized their flipped learning scenarios. Each pair implemented their designed scenario in a minimum of one and a maximum of three sessions within an established course, module, or unit at their respective higher education institution (HEI). Lecturers were encouraged to use the FLeDTool, patterns, and scaffolding resources as implementation guides and pedagogical support.

The pilot phase (implementation), conducted from February to June 2024, directly involved 34 university teachers and, indirectly, approximately 840 students from diverse disciplines. During this period, 20 of the 34 university teachers involved piloted the FLeD tool and designed and implemented 20 flexible learning scenarios and 52 learning sessions encompassing a range of delivery formats, including face-to-face, online, and blended modalities, and were applied at both bachelor’s and master’s degree levels.

3.2. Evaluation of Pilot Implementation

The evaluation of the pilot implementation of the FLeD framework and toolkit used a mixed-methods research approach integrating quantitative and qualitative methods (J. W. Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). The data collection instruments used in this study are diversified, as Table 1 illustrates.

Table 1.

Instruments to collect the data in the FLeD pilot.

Quantitative data collection used structured surveys of participating lecturers before and after the pilot. The FLeD tool’s integrated analytics system tracked user engagement, scenario creation, and the frequency of collaborative interactions on the platform, which provided an additional quantitative layer, revealing patterns in tool adoption and the types of learning designs most frequently developed and shared.

A qualitative approach was also chosen to capture in-depth comprehension of the challenges and opportunities associated with designing the flipped learning scenarios (J. B. Creswell, 2013). Qualitative data collection included (i) focus groups (FG), (ii) self-observation reports (SOR), and (iii) peer feedback reports (PFR). Focus group discussions (virtual or in person) facilitated collaborative reflection on participant experiences, knowledge-sharing, and identification of the challenges encountered during the design and implementation phases. The self-observation reports submitted by lecturers offered individual perspectives on the adaptation process, and the peer feedback reports captured observations and criticism on the design and execution of scenarios.

Data triangulation, which included cross-referencing survey results, FLeD platform analytics, focus group transcripts, self-observation reports and peer feedback reports, was used for a more robust analysis.

The pilots’ evaluation phase comprised post-pilot workshops to present and discuss preliminary findings with participants, providing a forum for member-checking and an opportunity to co-refine the FLeD resources in response to real-world feedback.

This methodological approach facilitated a refined understanding of the influence of FLeD patterns and digital resources on pedagogical practices and their role in supporting flexible, inclusive learning environments across higher education institutions.

3.3. Data Collection

3.3.1. Quantitative Design

To assess the effectiveness of the FLeD project, a pre- and post-survey was employed to collect quantitative data.

The pre-pilot survey, administered in December 2023, gathered baseline data on teachers’ attitudes and interests regarding flexible teaching, flipped classroom methodologies, collaborative learning, inclusion, digital technologies, and self-regulated learning. This survey consisted of 36 Likert-type items (scale 1–7); a sample question is: “Indicate which of the following statements best describes your attitude towards the use of new internet technologies for teaching and learning”.

The post-pilot survey, conducted in July 2024, measured changes in these dimensions and included 60 Likert-type items (scale 1–7); a sample question is:

“Indicate which of the following statements best describes your attitude towards incorporating flexible teaching and learning methods:

Additional items explored participants’ experiences with design patterns, scaffolding, training pathways, the tool, and inclusion. Furthermore, the impact of the FLeD project was extended through dissemination workshops held across multiple partner institutions from October to November 2024. These sessions engaged educators, academics, and stakeholders, fostering collaboration and knowledge-sharing in exploring innovative approaches to flexible learning. Workshops were delivered in face-to-face, hybrid, and online formats, with attendance ranging from 40 to 78 participants per institution. In some cases, satisfaction surveys were conducted to assess the impact of these workshops and refine future implementations.

An additional layer of quantitative data was provided by the FLeD tool’s integrated analytics system that tracked user engagement, scenario creation, and the frequency of collaborative interactions on the platform, providing a set of metrics for analysis.

3.3.2. Qualitative Design

To complement the quantitative data, several qualitative instruments were designed to capture deeper insights into the implementation and impact of the FLeD pilot.

A focus group was conducted at each institution (six FG) in July 2024, gathering teachers’ reflections on their pilot experience, identifying strengths and weaknesses of the provided resources, and assessing their effectiveness in designing flexible learning scenarios. Discussions also explored the future integration of emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, in flipped learning. A sample question used in the FG is: “How did you find the flipped classroom resources (patterns, FLeD tool, playful experience and peer feedback) in guiding you through the pilot program?”.

Additionally, a self-observation form was provided to participating teachers, allowing them to reflect on the changes made in their designs, implementation challenges, and prospects for improving flexibility, inclusion, and self-regulation. A sample question used in the self-observation form is: “Changes made (1) What specific changes have you made in your flipped learning implementation? Peer-feedback and co-design (1) How have you collaborated with your peers to co-design pre-class or in class- activities?”

A peer-feedback document, structured similarly to the self-observation form, was used by peer teachers to evaluate the effective implementation of their colleagues’ designs with a guide of questions. A sample question used in the peer-feedback report is: “(1) Describe your colleague’s practice of your observed scenario, (5) How were pre-class activities connected to the in-class activities?”. Furthermore, parallel studies on inclusion collected students’ and experts’ perspectives through focus groups, interviews, and questionnaires, evaluating how diverse learning strategies accommodate different needs.

3.3.3. Validation Procedures

To ensure the validity and reliability of the research instruments, several validation steps were implemented. The surveys and qualitative instruments were reviewed by experts in flexible learning and inclusion, ensuring their alignment with the research objectives. The triangulation method was applied by cross-referencing data from teacher surveys, focus groups, self-observations, and peer feedback, ensuring a comprehensive and multi-perspective analysis. Furthermore, an open call for external teachers attracted 36 educators from diverse educational levels, ranging from primary and secondary education to vocational, higher, and postgraduate education. Their feedback on the usefulness of the resources and implementation process was gathered through an online session, further validating the applicability of the FLeD resources.

3.3.4. Data Analysis

A mixed-methods approach was used to analyze the collected data. Quantitative survey data were processed using descriptive and inferential statistical analyses to measure changes in participants’ attitudes, skills, and perceptions regarding flexible learning. The qualitative data from focus groups, self-observations, and peer feedback were analyzed using thematic analysis, identifying key patterns in teachers’ experiences, challenges, and perceived effectiveness of the resources. Additionally, a parallel study on inclusion gathered student perspectives on inclusive learning strategies, with findings categorized according to themes such as special educational needs, ethnic and gender diversity, and accessibility.

4. Results

To evaluate the effectiveness and user perceptions of the FLeD project resources, a mixed-methods approach was employed, combining both quantitative and qualitative data. We present the results organized in terms of the research questions and the methodological approach.

4.1. Quantitative Analysis

Satisfaction Scores: Results from the Survey and Tool Usage Metrics (Technical Performance Metrics)

The pre- and post-pilot surveys administered to participating educators utilized a 7-point Likert scale to capture attitudes toward flexible teaching, flipped classroom methodologies, inclusivity, digital technologies, and student self-regulation. These instruments facilitated both descriptive and comparative analyses, allowing for the assessment of changes over time in participants’ perceptions and practices.

Regarding RQ1—How do university teachers perceive and engage with digital tools and pedagogical resources for designing flipped and flexible learning scenarios? The results from the post-survey and through the tool usage metrics (evaluation of the FLeD project’s resources and tools) indicate a generally high level of satisfaction across key dimensions as described in Table 2 and satisfaction with the tool.

Table 2.

Results from the survey—mean by dimension.

Specifically, the implementation of learning design patterns received a mean satisfaction score of 5.31 out of 7, suggesting that participants found the patterns effective in guiding pedagogical decisions. The scaffolding strategies provided for learning design scored 5.04 out of 7, indicating moderate to high perceived utility. The FLeD tool, while positively received overall, obtained a slightly lower average rating of 4.83 out of 7, reflecting both its potential and areas for improvement.

Further analysis of specific aspects revealed the highest satisfaction in relation to student collaboration (5.64/7) and self-regulated learning (5.57/7), highlighting the perceived effectiveness of the FLeD resources in fostering active and autonomous student engagement. The flexibility of the learning design also scored favorably (5.43/7), while the perceived inclusiveness of the designs was rated at 4.71/7, suggesting variability in experiences regarding accommodating diverse learning preferences. Notably, the ease of use of the tool was rated lowest at 4.29/7, indicating challenges related to navigation and usability that warrant further refinement.

These findings provide evidence of the strengths and limitations of the FLeD initiative and offer valuable insights for future iterations aimed at enhancing the user experience and pedagogical impact.

The quantitative data from the survey revealed variability in responses, with score ranges between 2 and 7 across different dimensions. This variability offered insights not only into the mean values but also into the distribution and consistency of responses, informing an understanding of how the intervention was experienced across diverse institutional and disciplinary contexts. The analysis of these data was supplemented by qualitative methods, including focus groups, peer feedback sessions, and self-reflection exercises, which provided contextual depth and interpretive richness to the survey results. This triangulated methodological approach enhanced the validity and reliability of the findings by capturing both measurable trends and experiential nuances within the implementation process.

The FLeD tool was tested by 34 educators from six universities across five European countries participated in testing the tool and providing feedback.

- Usability findings

Usability emerged as a prominent theme in the post-pilot evaluation. Educators generally found the FLeD tool valuable for organizing and structuring teaching activities, although some participants initially encountered difficulties due to its nonlinear interface design. The mean satisfaction score for tool usability was 4.29 out of 7, the lowest among measured categories, reflecting mixed experiences with interface intuitiveness and navigation. However, user feedback indicated that, once familiarized, the tool significantly aided in lesson framing and systematizing instructional strategies. This dichotomy suggests that while the tool offers high pedagogical utility, its user experience design could benefit from refinement to reduce the initial learning curve.

- Integration success rates

The FLeD tool demonstrated considerable success in being integrated into existing teaching practices across institutions and disciplines. Teachers from multiple universities reported that the tool, along with its associated learning design patterns, helped them systematize planning, enhance student engagement, and improve self-regulated learning. The tool’s integration into both face-to-face and online environments, and across bachelor’s and master’s level courses, reflects a high degree of adaptability and contextual fit. Additionally, collaborative features such as design sharing, feedback exchange, and community interactions were successfully utilized, further indicating effective integration into professional teaching routines.

- Language support effectiveness

The FLeD tool includes multilingual support, offering platform translations and instructional resources in six languages, thereby enhancing accessibility for educators across varied linguistic and cultural contexts. This ensures that educators from different countries can navigate the tool, understand the recommendations, and implement the patterns without language being a barrier, which is critical for a transnational European project.

In sum, we may say that these findings support H1, as teachers reported positive perceptions of the flexibility (M = 5.43/7), inclusiveness (M = 4.71/7), and support for student self-regulation (M = 5.57/7) provided by the FLeD toolkit and learning design patterns.

4.2. Qualitative Findings

Within the following sections, the main results related to the challenges, opportunities, and effectiveness of the resources within the context of the FLeD project and future improvements have been analyzed.

Regarding RQ2—What challenges and enablers do faculty encounter when implementing flipped learning in diverse higher education contexts? The results are based on the thematic analysis from the focus group (FG), self-observation report (SOR), and peer feedback (PFR). As referred to above, a total of six FG were conducted and 15 responses were collected in the SOR and PF reports. The results are presented in terms of the categories of responses (challenges, opportunities), including some quotations from the FGs are included in consideration of the institution, while SOR and PF are presented by the respondents.

4.2.1. Challenges

The analysis of the FG detected some challenges faced by the participants, including technical issues, particularly with the usability of the tool. Several teachers found these tools to be difficult to integrate into their existing teaching practices, resulting in frustration and inefficiency.

“The tool is just another tool. It helps to plan, but I have already planned it in another format. I don’t need a tool that forces me to put all sessions and resources in each case”.(UAB, FG)

The FC model also posed challenges in ensuring pre-class participation and engagement, with many students failing to complete tasks that would allow for a productive class session. Similarly, in the self-reflection report, one participant noted the need for prior preparation, which reinforces the need for proactive engagement strategies.

“Only 30% of the students did the FC activity… those who did gave good feedback, but it’s difficult to say if it had a real impact on their final grade”.(UPF, FG)

“The primary challenges in implementing the design were ensuring student engagement and managing time effectively during activities. To address these, I used interactive elements to maintain interest and established clear time limits for each activity to keep the class on track.”(R4, SOR)

“One of the challenges was to get students to do their homework at home”(R1, SOR)

Another significant challenge across both reports (FG and SOR) was time management. Teachers in both cases indicated difficulty in managing the pacing of activities and aligning the content within limited course durations, which they attributed to logistical constraints and varied student participation rates.

“The schedules of the tasks and demands in the pilot were short in time… I could not dedicate the time I would have liked”.(TU, FG)

Furthermore, better organization of activities was emphasized across the reports. In the FGs, participants noted that clearer planning and a more structured approach to FC design would help improve student engagement. In the self-observation, there was a desire to blend FC with traditional teaching.

“I think I will encapsulate the flipped classrooms not in single topics but across topics. I will keep the flipped activities interleaved with traditional lectures but will make them shorter”.(R5, SOR)

4.2.2. Opportunities

The analysis of the FG also highlighted opportunities presented by the project, including the chance for pedagogical innovation, where many teachers recognized the value of using the FC model and associated digital tools to enhance student engagement and autonomy, a sentiment echoed in the self-reflection data (SOR).

“It helped to create the responsibility. You are at the university; if you think that you can stay without doing previous work, you can’t”.(UAB, FG)

“My experience is positive. What I liked the most were the resources and the theoretical support of the project, which seems to me to be very good.”(UAb, FG)

“The students come prepared from home, which helps them to get a good grounding in the subject matter”(R1, SOR)

The collaboration fostered by the project allowed teachers to share best practices and learn from each other, as highlighted by the responses to the FG and the SOR.

“The collaboration during the pilot/training has been positive to create knowledge sharing”.(UPF)

“I found the FLeD Tool particularly useful for structuring my learning journey. The resources made the content more interactive, and the peer feedback allowed for constructive collaboration and continuous progress during the program.”(UiS, FG)

“Peer collaboration is key to the proper functioning of this methodology, as the synchrony and understanding of those who have been part of the design and implementation, allows better deal with any unforeseen events that may arise. It also makes us flexible to be involved in different phases of the process, as we are aware of everything.”(R8, PF)

The use of gamification elements also showed the potential to make learning more engaging.

“They gave themselves points for clarity of presentation, creativity, analysis… the teams themselves among themselves evaluated and gave feedback”.(SU, FG)

Additionally, teachers appreciated the availability of open educational resources (OER), which helped them save time while offering more flexible and inclusive learning environments.

“Teachers were very happy to learn about new tools and resources that are openly available on the Internet… it’s very time-consuming to find resources, and these platforms help by bringing them all into one place”(UPF, FG)

The participants employed various adaptation strategies to accommodate different learning preferences and abilities in their FCs models. In the self-observation report, these were the strategies reported.

4.2.3. Future Developments

Within the FG and SOR, future reflections emphasized the need for improved collaboration features within digital tools and more streamlined tools that align better with existing teaching methods.

“It would be very useful if we could have more flexibility to adapt the tools to our teaching styles”.(TU, FG)

“We need more time allocated for group activities”.(R2, SOR)

Inclusivity was also a focus for improvement.

“I will include clearer instructions for students with SEN. I will include additional electronic resources on each of the topics as students show interest in the course issues”.(R12, SOR)

Additionally, gradual autonomy was proposed.

“In order to gradually work on autonomy, it would be necessary at the beginning of the year to do the activities during class time and, little by little, introduce students to do them at home”.(R3, SOR)

There was also a call for more structured, flexible training that allows teachers to experiment with and implement innovative teaching practices without feeling overwhelmed.

“The experience was positive because I had the feeling of always having access to a structure that somehow also forced me to plan my teaching activities more”.(UPF, FG)

The role of AI in both enhancing teaching and supporting personalized learning experiences was recognized, though concerns over ethical implications and academic integrity were also raised.

“AI will be inevitable… we will have to face difficulties like information validity and ethical issues”.(UPF, FG)

“AI can help identify students’ learning levels and potential difficulties, allowing for tailored educational experiences that accommodate various learning styles”.(SU, FG)

“I want to keep improving current designs and working with new technologies and artificial intelligence (AI).”(R15, SOR)

Looking ahead, the need for ongoing professional development and support for educators in using digital tools and adapting to flexible learning environments was a common theme. In the self-reflection report, one teacher acknowledged the necessity of improving digital competencies. This matches the focus group concerns, where teachers expressed the need for more user-friendly tools and comprehensive training to better integrate technology into their teaching practices.

“For the future, I believe it would be beneficial to address the new challenges that come with deepening the Digital Competence for Educators”.(R8)

Following valuable insights gathered during the pilot phase, the development team has incorporated a series of refinements into the FLeD learning design tool. These enhancements emerged from a collaborative consensus and prioritization process among project partners, ensuring that user feedback played a central role in shaping improvements. The refinements were implemented after evaluating their pedagogical impact and technical feasibility in consultation with expert developers, with the overarching goal of enhancing flexibility, inclusivity, usability, and overall user experience.

One of the most significant refinements is the introduction of the “Combined Pattern”, a feature developed in response to educators’ need for greater design flexibility. This addition allows teachers to integrate elements from the three existing patterns: constructive feedback, prior preparations, and team regulation, offering a more adaptable approach to learning design. In response to user feedback highlighting the need for clearer navigation and design identification, the tool now displays the pattern type within each lesson description. This enhancement makes it easier for educators to recognize and explore different design structures, improving overall usability.

Inclusivity has been a key focus of the refinements, leading to the integration of a feature that enables teachers to specify the number of SEND (Special Educational Needs and Disabilities) students and indicate their specific needs. This functionality has been embedded within the inclusiveness and self-regulation section, ensuring that learning designs better accommodate diverse student requirements. Additionally, usability improvements, such as an enhanced activity calendar with a scroll button and magnifying lens, were introduced to facilitate smoother navigation and interaction.

Other refinements were guided by the need to enhance efficiency and accessibility. A frequently requested feature—the ability to duplicate tasks within any session—has been implemented, simplifying the process of structuring learning activities. Updates to the community feature now provide a more accurate reflection of user contributions, fostering greater engagement among platform members.

To support educators in their design process, the visibility of the scaffolding tab has been improved, ensuring easier access to guidance throughout learning design activities. Another highly requested feature—the ability to download learning scenarios in PDF format—has been introduced, allowing educators to effortlessly export and share their designs. Additionally, recognizing the diverse linguistic backgrounds of its users and the need for broader accessibility, the platform has been fully translated into six languages: Catalan, Spanish, Norwegian, Italian, Bulgarian, and Portuguese. This ensures that educators across different regions can navigate and utilize the tool more effectively, fostering greater inclusivity and engagement.

These refinements highlight a commitment to continuous improvement, ensuring that the tool evolves in response to educators’ needs. By incorporating user insights from testing and implementation, the platform has become more dynamic, inclusive, and adaptable to diverse teaching and learning contexts.

To conclude, the analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data sets has revealed a range of technical and pedagogical enablers, including scaffolding strategies, peer collaboration, and gamification, which support H2. The identification of challenges—such as time constraints and tool usability—complements these findings.

Regarding RQ3—To what extend do the FLeD resources (patterns, scaffolds, and FLeD tool) support inclusive teaching practices and address student diversity? the results from the qualitative instruments point to the following conclusions:

Inclusivity was another concern, as teachers grappled with accommodating students from diverse backgrounds, including those with disabilities or language barriers. In the self-reflection report, similar challenges are noted. R13 acknowledged challenges in ensuring inclusivity, suggesting that real-time feedback tools could enhance support for diverse learners.

“… the critical need to modify teaching techniques to meet the diverse needs of students, ensuring that each student was actively involved and supported throughout the learning process”.(UiS, FG)

The responses about inclusivity (UAB, UT, SU) revealed valuable insights into the effectiveness of the FLeD resources and flipped classroom (FC) model in promoting inclusive learning environments. While students generally perceived their courses as inclusive and fair, they highlighted areas for improvement, particularly in accessibility for SEND students and the personalization of learning activities. Students from all three universities appreciated the flexibility of learning activities, with UAB students noting the adaptability of deadlines and materials. However, some students expressed concerns about accommodating students with visual or auditory impairments, with one remarking, “Despite being someone who is not disabled in any capacity, I think that perhaps courses are not fully adapted to people who experience visual or auditory impairment” (E3). This concern was echoed at Trento and Sofia, where students emphasized the need for personalized accommodations to support diverse learning preferences and abilities.

The learning resources were mostly seen as accessible, though students highlighted gaps in digital accessibility and the need for better resources for SEND students. At UAB, students valued the variety of materials provided, such as “mind maps, full texts, and summarized texts” (E5), which helped them engage with the content. However, students from Trento noted the necessity for clearer communication and resources that reduce teacher dependency, with one student observing, “There is a need to interact directly with professors very often, even for particularly delicate areas” (F). A significant recommendation from students across all three universities was the inclusion of assistive technologies such as subtitles, readable fonts, and audio dubbing to better support students with diverse needs.

Regarding teamwork and gender inclusion, students at UAB appreciated the intentional effort to create diverse groups, fostering an inclusive environment where different perspectives were valued. One student mentioned, “Different ideas and different ways of looking at things enrich teamwork, allowing for a deeper understanding of the subject studied” (E5). However, there was limited awareness of gender representation in course materials, with one student noting, “The focus is more on concepts rather than academic personalities. The discussions in class are not centered on individuals—neither men nor women” (E2). This suggests the need for greater attention to gender representation in academic references and materials to ensure diverse voices are included in learning contexts.

Overall, while students found the flipped classroom model largely inclusive, they recommended further improvements, such as enhanced accessibility, more personalized learning, improved communication, and fairer assessment strategies to ensure a truly inclusive and equitable learning experience.

Furthermore, these findings are consistent with the H3, thus suggesting that teachers perceive the FLeD materials as contributing to inclusive pedagogical approaches and addressing student diversity. However, we have identified challenges related to the comprehensive implementation of inclusivity for students with special needs or language barriers.

Regarding RQ4—What impact does the FLeD pilot have on student engagement, self-regulated learning, and collaboration in flipped classroom settings? The results from the survey and from the FG highlight the effectiveness of the FLeD resources and the flipped classroom (FC) approach was widely acknowledged by teachers within the FG, particularly for its ability to structure teaching activities, enhance student engagement, and support inclusivity and innovation. The usability of the FLeD tool was central to this effectiveness, as many teachers found it useful for organizing lessons and structuring activities. Despite some initial struggles with its non-linear design, teachers from institutions like UPF and UT noted that once familiar with the tool, it helped them frame and systematize their teaching process. The tool was particularly valued for its instructional support and clear guidance in lesson planning.

“The tool helped me better frame my activities… it was a bit complicated at first, but once I got used to it, it worked better”.(UT)

The learning design patterns provided teachers with a structured framework that significantly improved their planning and organization. Teachers reported that the patterns guided them in promoting self-regulated learning and ensuring students were better prepared for classroom activities. Furthermore, teachers observed a marked improvement in student focus and engagement, particularly when patterns encouraged prior preparation, peer feedback, and collaborative learning.

“I believe that this helped them be more prepared to face possible demands that could arise from students”.(UPF)

“In the classroom, I see them more prepared and more focused”.(UAB)

The integration of gamification and peer feedback also contributed to higher participation and student interest.

“The implementation of gamification further piqued student interest, leading to high participation rates in the sessions despite challenges like work and other commitments”.(SU)

The FLeD resources also made significant strides in promoting inclusivity, innovation, and digitalization. Teachers were guided to consider gender perspectives, special educational needs, and disabilities (SEND), and accessibility, though some found it challenging to fully implement inclusivity without detailed knowledge of students’ needs. For example, one teacher said:

“I followed the recommendation of publishing the tasks on Monday due to a gender perspective. I also designed the tasks thinking that special needs students could follow them”.(UPF)

In terms of innovation, the shift towards student-centered learning was seen as highly effective in fostering critical thinking and self-regulation.

“The implementation of the flipped classroom was quite innovative in that it moved away from traditional lecture-based teaching to a more student-centered approach”.(UiS)

Finally, digitalization played a crucial role in enabling flexible learning pathways and fostering student collaboration.

“Digital tools enabled peer collaboration and feedback, helping to create a connected learning community even in a remote or hybrid setting”.(UiS)

Overall, as defended by the participants in the FG, the FLeD project helped teachers create more dynamic, inclusive, and engaging learning environments, significantly improving student preparedness and participation.

In sum, the findings offer evidence for H4, with faculty members reporting enhanced student engagement, collaboration, and self-regulation concomitant with the use of FLeD-supported flipped scenarios.

Concerning RQ5—How does participating in the collaborative design and implementation of flipped scenarios influence teachers’ pedagogical innovation and reflection? nevertheless, considering the responses given by participants in the self-observation report (SOR), five participants emphasized the need to be flexible and to reconsider their approach based on factors like student engagement, lesson dynamics, or unforeseen circumstances. Two participants used the implementation process as an opportunity to reflect on their design, resulting in more thoughtful planning or revisions for future iterations. Six people followed the original design closely, with either no or minimal changes, highlighting either satisfaction with the original design or limitations in altering plans.

The reflections highlight varying levels of change in implementing flipped learning, ranging from no changes to significant pedagogical shifts. While some participants found their original designs effective, others adapted based on student needs, teaching format, and contextual challenges. Finally, the reflections underscore the importance of flexibility and continual reflection in optimizing flipped learning approaches.

The participants employed various adaptation strategies based on the FLeD given resources to accommodate different learning preferences and abilities in their FC models as reported in the self-observation. They were mainly oriented to prompt a personalized, flexible, and inclusive learning experience:

- Varied teaching methods: teachers utilized diverse instructional methods to cater to different learning styles. For instance, R1 used multimodal teaching, combining oral explanations, PowerPoint presentations, and collaborative activities for both large and small groups. R5 allowed students to choose how they participated, such as using platforms like Wooclap for interaction, promoting engagement through varied methods.

- Flexibility and autonomy: several participants emphasized giving students more control over their learning. R3 allowed students to engage with pre-class materials at their own pace by providing questionnaires and activities in advance. Similarly, R10 offered students a variety of task options, enabling them to choose how to complete assignments based on their preferences.

- Communication and support: effective communication was key to supporting diverse learners. R6 highlighted the use of clear communication plans and the provision of external resources via the Learning Management System (LMS) to guide students through course expectations. R12 and R4 focused on individualized support, offering extra time, feedback, and additional resources for students with special needs like dyslexia or language barriers.

- Understanding learner needs: teachers assessed and adapted to students’ individual needs through surveys and by observing group dynamics. For example, R6 used surveys to gather information on students’ backgrounds and challenges, allowing them to tailor instruction effectively. R7 adjusted workshop dynamics based on the group’s digital skills and preferences.

- Scaffolded support and regulation: scaffolding strategies were used to help students manage their learning. R8 emphasized enabling students to self-regulate their learning through pre-workshop forms and constant check-ins, while also maintaining flexibility in response to students’ varied needs. R12 extended deadlines and offered additional resources for students who required extra time to engage.

In sum, the findings also support H5, as participation in collaborative design and implementation encouraged pedagogical innovation, experimentation, and reflective practice among faculty members.

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The FLeD project was developed in response to the increasing demand for flexible, inclusive, and digitally mediated higher education, particularly following the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. The European Commission’s goals for digital transformation in education align with FLeD’s theoretical foundation of flipped learning (FL), inclusive design, and digital pedagogy. The FLeD pilot study’s key research questions focus on whether structured pedagogical support, provided through tools like the FLeD platform and its associated resources, could empower educators to implement flexible, inclusive, and effective flipped classroom scenarios.

The results of the collected data analysis indicate improvements in instructional design, student engagement, and self-regulated learning, in line with the initial assumptions. These outcomes corroborate earlier research highlighting the benefits of flipped learning in promoting active and student-centered learning (Birgili et al., 2021; Bredow et al., 2021). The teachers in the pilot particularly valued the FLeD design patterns and support in overcoming the challenges of digital learning environments, a topic extensively researched in studies on digital competence (Starkey, 2019; Fernández-Batanero et al., 2022).

However, the lowest rate obtained by the tool usability dimension reveals a limitation consistent with previous studies emphasizing the importance of adequate usability design and training when introducing new technologies (Lay et al., 2020; Albó & Hernández-Leo, 2021).

The results in the FLeD pilot study provide evidence that learning design tools, when combined with structured pedagogical patterns, gamified engagement, and inclusive design strategies, can result in significant changes to teaching practices and student outcomes.

Concerning inclusivity issues, the multilingual and multimodal approach enhanced accessibility, and collaborative design activities enabled peer learning and professional development. Moreover, the integration of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles ensures attention to inclusion, although qualitative feedback from students and teachers suggests this is an ongoing area for development.

Results indicate that the FLeD framework is consistent with current trends in higher education, which aim to promote inclusivity, flexibility, and student autonomy (Houlden & Veletsianos, 2021). Furthermore, it shifts faculty development from passive training toward active, community-driven co-design—an approach supported by connectivism and social constructivism principles.

However, despite its positive outcomes, the pilot study results highlighted areas for improvement:

- Tool usability: the initial engagement was compromised by the non-linear and complex interface of the FLeD tool, which highlights a disconnect between the pedagogical vision and user experience (UX) design that must be addressed in future iterations.

- Inclusivity in practice: while teachers appreciated the inclusive guidance, its implementation was inconsistent. Some educators found it difficult to adapt materials for students with SEND and lacked insight into their learners’ specific needs. Hence, a more integrated approach to learner profiling and real-time feedback tools could help to bridge this gap.

- Student autonomy challenges: low pre-class participation, a common challenge in flipped models, was evident in this pilot study. This reiterates the findings of Sein-Echaluce et al. (2024), who found that, without structured support, students may struggle with the self-regulation demands of FL environments.

- Time constraints: teachers noted a lack of time for meaningful engagement with the tool and iterative refinement, suggesting the need for lighter onboarding processes or modular training.

The findings presented and analyzed in this study provide clear and consistent support for our exploratory hypotheses, each of which aligns with the research questions initially proposed.

Teachers had a positive view of the flexibility, inclusiveness, and support for student self-regulation offered by the FLeD toolkit and learning design patterns, which supports H1. These results are consistent with existing research that emphasizes the importance of structured, flexible frameworks in flipped learning contexts (Lo, 2023; Albó et al., 2024; Noguera et al., 2022). The second hypothesis was supported through the identification of key technical and pedagogical enablers, including scaffolding strategies, peer collaboration, and gamification features integrated into the FLeD design. Faculty also highlighted challenges such as time constraints and tool usability, reflecting commonly reported implementation barriers (Albó & Hernández-Leo, 2021; Baig & Yadegaridehkordi, 2023; Agostini et al., 2024). The participants’ recognition of FLeD’s role in supporting inclusive practices, particularly through the availability of multilingual resources and pattern-based supports, was evidence of H3. Nevertheless, challenges remained, especially about ensuring accessibility for students with special needs and language diversity—issues also reported in previous work on UDL and digital inclusion (A. Meyer et al., 2014; Sosa-Díaz et al., 2021; Soriano et al., 2017). Regarding H4, it was confirmed by teachers’ reports of enhanced student engagement, collaboration, and self-regulated learning when implementing FLeD-supported scenarios. These perceptions align with meta-analyses and empirical findings on the positive learning outcomes associated with well-designed flipped classroom interventions (Bredow et al., 2021; Birgili et al., 2021; Albó et al., 2024). Faculty reflections on how participation in the co-design and implementation of flipped scenarios promoted pedagogical innovation and reflective teaching provided support for H5, evidenced in the adoption of new strategies and experimentation with learning designs across institutions, aligning with prior literature on faculty development and design-based collaboration (Starkey, 2019; Albó et al., 2024; Nørgård et al., 2017).

These results evidence that the research questions were addressed and provide empirical and theoretical support for the FLeD framework as an effective tool to foster flexible, inclusive, and engaging learning environments in higher education.