As previously mentioned, the questions of the questionnaire used for acquiring the data were divided into two groups. Consequently, the results are going to be presented in a similar way. First, the demographics results characterized the sample and analyzed the topic of the research. The second set of questions supplied the data that answered the research questions.

4.1. Demographics

The study included 64 early childhood education teachers, the majority of whom were aged between 31 and 40, comprising 39.1% of the participants. This group was followed by those under 30 years old, who represented 23.4%, while 20% of participants were aged between 41 and 50, and 17.2% were between 51 and 60 years old. Regarding the participants’ marital status, the majority of teachers were married, accounting for 68.8%, followed by single teachers at 25%, and only 6.3% were divorced.

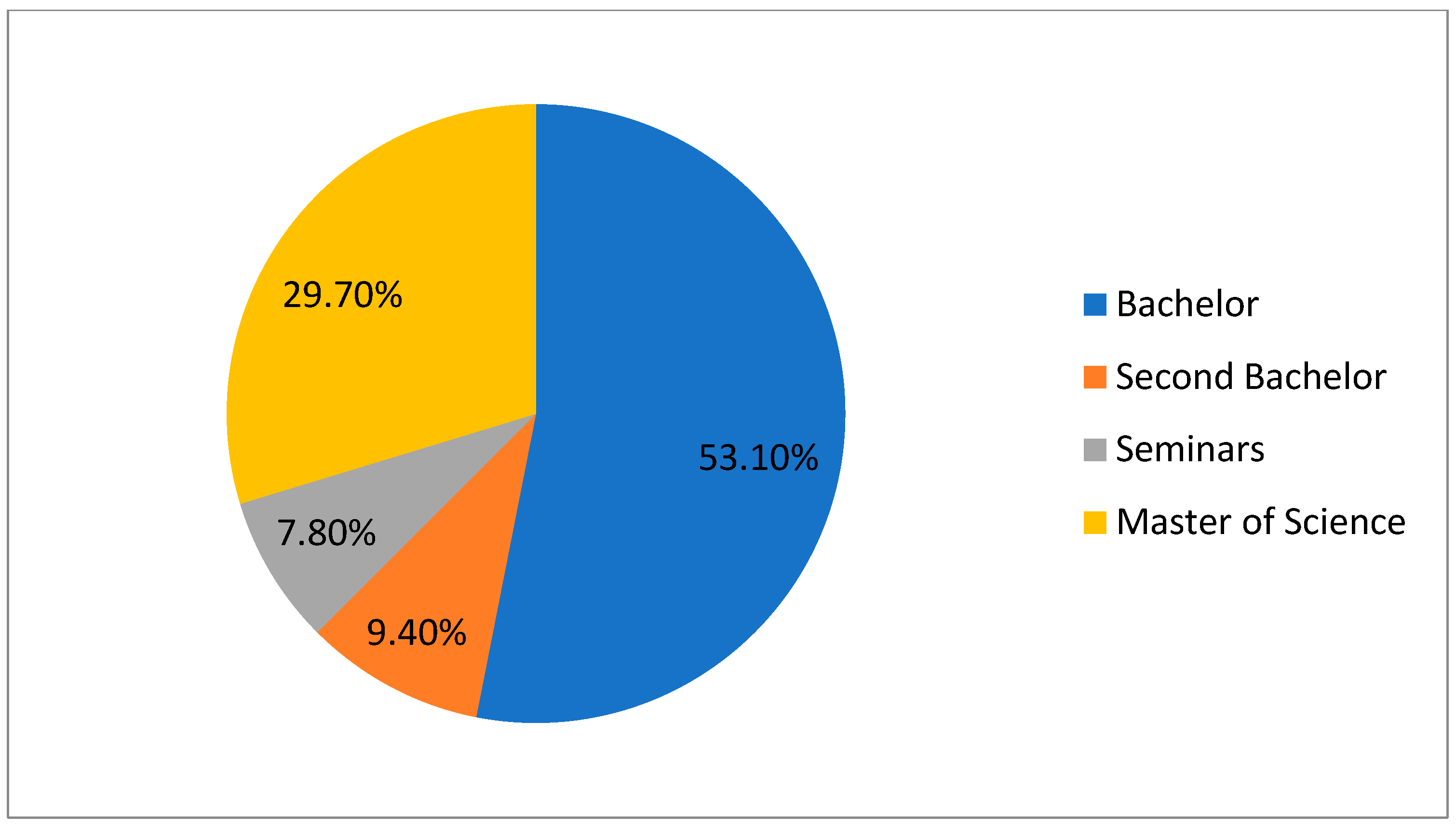

Regarding the educational level of the participants and their occupation,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 provide the information. Most teachers appeared to hold a basic degree, at 53.1%, followed by those with a postgraduate degree at 29.7%, while most participants were kindergarten teachers, at 62.4%, followed by nursery teachers and nursery teacher assistants, each at 18.8%.

Concerning the institution in which they are employed, most participants work in public nursery schools, at 59.4%, followed by employees in private kindergartens, at 17.2%, and 15.6% in public kindergartens, and only 7.8% in private nursery schools. Regarding their years of experience,

Figure 4 presents the participants’ work experience, revealing that most participants claimed to have worked for up to 5 years, at 25%, followed by those with 11–15 years of experience at 23%.

4.2. Teachers’ Perceptions on the Role of SSs in Fostering Environmental Awareness in Young Children During Early Childhood Education

The main part of the research dealt with teachers’ views on the role of sustainable schools in shaping the environmental awareness of early childhood children. Thus, initially, the early childhood educators were requested to indicate the extent to which they are familiar with the concept of sustainability. The majority indicated that they were “moderately” familiar, at 40.6%. Additionally, 20.3% stated that they were “very” familiar, and 9.4% considered themselves “extremely” familiar. Only 6.3% reported being “not at all” familiar, while 23.4% described their familiarity as “slightly.” Following that, they were asked whether they were aware of Sustainable Schools, with most of them answering positively at 53.1%.

Then, the participants were provided with a set of criteria for a Sustainable School and were asked to identify which ones they deemed the most essential.

Table 1 provides insightful data on the important criteria of a SS, as reflected in the mean values across different dimensions. Each criterion is rated on a scale from 1 to 5, with higher mean values indicating greater importance.

The mean value of the Promotion of Ecological Protection is 4.437, indicating that promoting ecological protection is a top priority for SSs. Sustainable development increasingly recognizes environmental education as crucial. The adherence to sustainability principles has a high mean value (4.3281), indicating that schools place significant importance on adhering to sustainability principles. The criteria for enhancement of physical/spiritual health and the opening of the school to the community have the same mean value (4.2654), suggesting a widespread recognition of their importance. Generally, schools value all criteria, with mean ratings above 4. Although some criteria exhibit greater variability in how they are prioritized by different schools, the low to moderate standard deviations suggest consensus on their importance.

At that point, participants were given some characteristics of a SS and were asked to indicate which ones they considered the most fundamental.

As indicated in

Table 2, all characteristics were deemed highly important, with the strongest endorsement for the notion that “a modern school should promote issues of environmental awareness, culture, equality, economy, management of natural resources, human rights, etc., beyond the curriculum” (4.5625). It was also affirmed that “experiential activities and educational visits designed to enhance students’ environmental, cultural, and social awareness contribute significantly to the effectiveness of knowledge delivery and skill development.” The increase of recyclable materials given for recycling is considered a necessary feature of a modern school. Especially, the high mean value of the opportunities for teacher training (4.6563) indicates that a modern school should provide teachers with opportunities to train in new teaching and organizational approaches. The findings suggest that educators place high values on professional development, recognizing its importance in improving the quality of education. Moreover, the high mean value of the promotion of Environmental Awareness, Culture, Equality, etc., (4.5625) shows that broader issues beyond the curriculum should be promoted in modern schools, such as environmental awareness, culture, and equality. Equal to the promotion of Environmental Awareness, Culture, Equality, etc., is the criterion of Extracurricular Events and Educational Visits. Moreover, the mean value of increasing recyclable materials (4.5156) indicates that several respondents agreed with the importance of sustainability practices in schools.

Thereafter, the survey then inquired about the extent to which teachers engage in actions that promote environmental sustainability within their school.

Table 3 illustrates a range of actions that foster environmental sustainability within a school unit. The mean values offer valuable insights into which actions are regarded as the most impactful.

According to the results of the above table, recycling is the major factor that can promote environmental sustainability in schools and has the highest mean value (4.0781). The promotion of environmental awareness is another important factor that contributes to sustainability (mean value: 4.0625). Also, the high mean value of increasing recyclable materials (3.9375) indicates that respondents generally agree that increased recycling is one of the most important features of a modern school. Within the educational environment, sustainability practices are widely recognized as an important component. Finally, energy and water saving (3.8125) technologies are recognized as crucial criteria, demonstrating strong consensus for the need for modern schools to be energy-efficient and water-saving.

The participants were subsequently asked to indicate the extent to which they engage in actions that promote social sustainability within their school (

Table 4). The results revealed that the most frequently implemented actions focus on fostering positive relationships (4.1406) and values (4.1875), as well as encouraging family involvement (3.9844).

Following that, the participants were then asked about the factors that motivate the adoption of sustainable development principles, with a focus on enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of the school (

Table 5). The most strongly supported reasons included waste reduction, energy consumption reduction, the implementation of an organized recycling program, and the overall improvement of the school’s operational efficiency.

Regarding the factors that contribute to greater productivity among students attending a SS,

Table 6 presents teachers’ perspectives.

According to

Table 6, Teachers’ believe that students who are well-informed about environmental issues are more likely to engage in sustainable practices and address environmental challenges because they acquire environmental knowledge. Moreover, the formation of ecological consciousness has a high mean value (4.5313), showing that schools must integrate environmental consciousness into their curriculum and activities to help students develop an awareness and attitude towards the environment and to foster responsible and environmentally responsible behaviors. Finally, the high mean value of the awareness of environmental issues (4.5156) highlights the importance of this factor.

Subsequently, the participating teachers were asked whether they believe that educators working in Sustainable Schools experience higher levels of satisfaction with their professional activities. The majority, 78.1%, reported being either very or extremely satisfied, while 18.8% expressed moderate satisfaction, and 3.1% indicated minimal satisfaction. Regarding whether they believe the school can contribute to the culture of sustainable development, the majority of teachers, 93.7%, strongly agreed or agreed with this statement.

Finally, the participants were asked whether they regarded the transformation of a conventional school into a sustainable one as important and beneficial. A significant majority of teachers, specifically 92.2%, expressed strong agreement or agreement with this view.

4.3. Cluster Analysis

A cluster analysis typology was developed to identify similar groups of school units based on sustainability, highlighting the similarities and differences among the clusters (

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9).

According to

Table 7, in the C1 cluster, most of the teachers are aged between 41 and 50 (44%), followed by 31–40 (28%), 51–60 (20%), and the least up to 30 (8%). In the C2 cluster most of the teachers are aged between 31 and 40 (41.2%), followed by teachers that are under 30 (35.2%), 41–50 (17.7%), and the least being 51–60 (5.9%). In the C3 cluster it was mostly teachers aged 31–40 (40.9%), followed closely by up to 30 (31.8%), 41–50 (18.2%), and 51–60 (9.1%).

As presented in

Table 8, the educational qualifications of teachers are outlined for each cluster. According to the results in the C1 cluster, most teachers hold a bachelor’s degree (44%), followed by seminars (32%), master’s (16%), and second bachelor’s (8%). In the C2 cluster, the majority have a bachelor’s degree (76.5%), followed by a master’s (17.6%), and a few attended seminars (5.9%); no teachers held a second bachelor’s degree. Finally, in the C3 cluster, a significant proportion holds a master’s degree (50%), followed by a second bachelor’s (27.3%), a bachelor’s (13.6%), and seminars (9.1%).

This profile of clusters analyzes the motivations behind adopting sustainable development practices in schools within each cluster. In the C1 cluster, the main reason why adopting the philosophy of sustainable development enhances school efficiency is waste reduction (32%), followed by energy consumption reduction (28%), limitation of expenditure of resources (24%), and organized recycling programs (16%). In the C2 cluster the main reason why adopting the philosophy of sustainable development enhances school efficiency is the organized recycling program (41.2%), followed by waste reduction and energy consumption reduction (both at 23.5%), and lastly limitation of expenditure of resources (11.8%). In the C3 cluster the main reason why adopting the philosophy of sustainable development enhances school efficiency is the organized recycling program (40.9%), followed by waste reduction (27.3%), energy consumption reduction (18.2%), and limitation of expenditure of resources (13.6%).

More specifically, the C1 cluster consists of middle-aged teachers who hold a bachelor’s degree, and the main motivation for sustainable development is waste reduction. The C2 cluster consists of teachers that are between 31 and 40 years old; the majority hold a bachelor’s degree, and the main motivation for sustainable development is the organized recycling programs. The C3 cluster consists of teachers that are between 31 and 40 years old; the majority hold a master’s degree, and the main motivation for sustainable development is the organized recycling programs.