A Narrative Inquiry into the Cultivation of a Classroom Knowledge Community in a Chinese Normal University

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Backdrop

2.1. Knowledge Community

2.2. Teacher Knowledge Community

2.3. Classroom Knowledge Community

3. Research Method

3.1. Narrative Inquiry

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Four Interpretive Tools

3.4. Participants

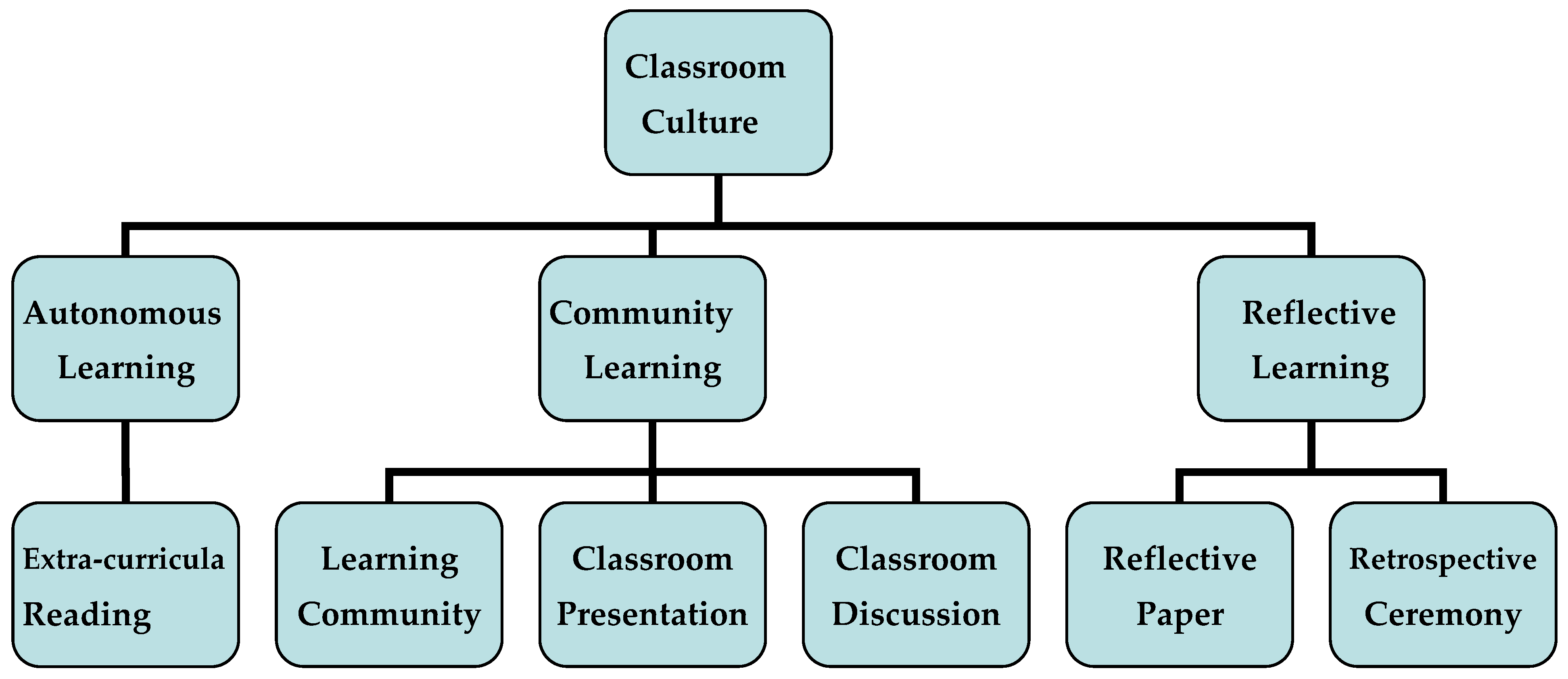

4. Cultivation of the Classroom Knowledge Community

4.1. The Author’s Narrative of Course Enactment

4.1.1. Classroom Culture: Authenticity

4.1.2. Learning Community: Rotation of Roles

4.1.3. Classroom Presentation: “Speak It Out”

4.1.4. Classroom Discussion: “I Have a Question”

4.1.5. Extra-Curricula Reading: “Go to the Library”

4.1.6. A Reflective Paper: “Think It Over”

4.1.7. A Retrospective Ceremony: Growth

4.1.8. Comments

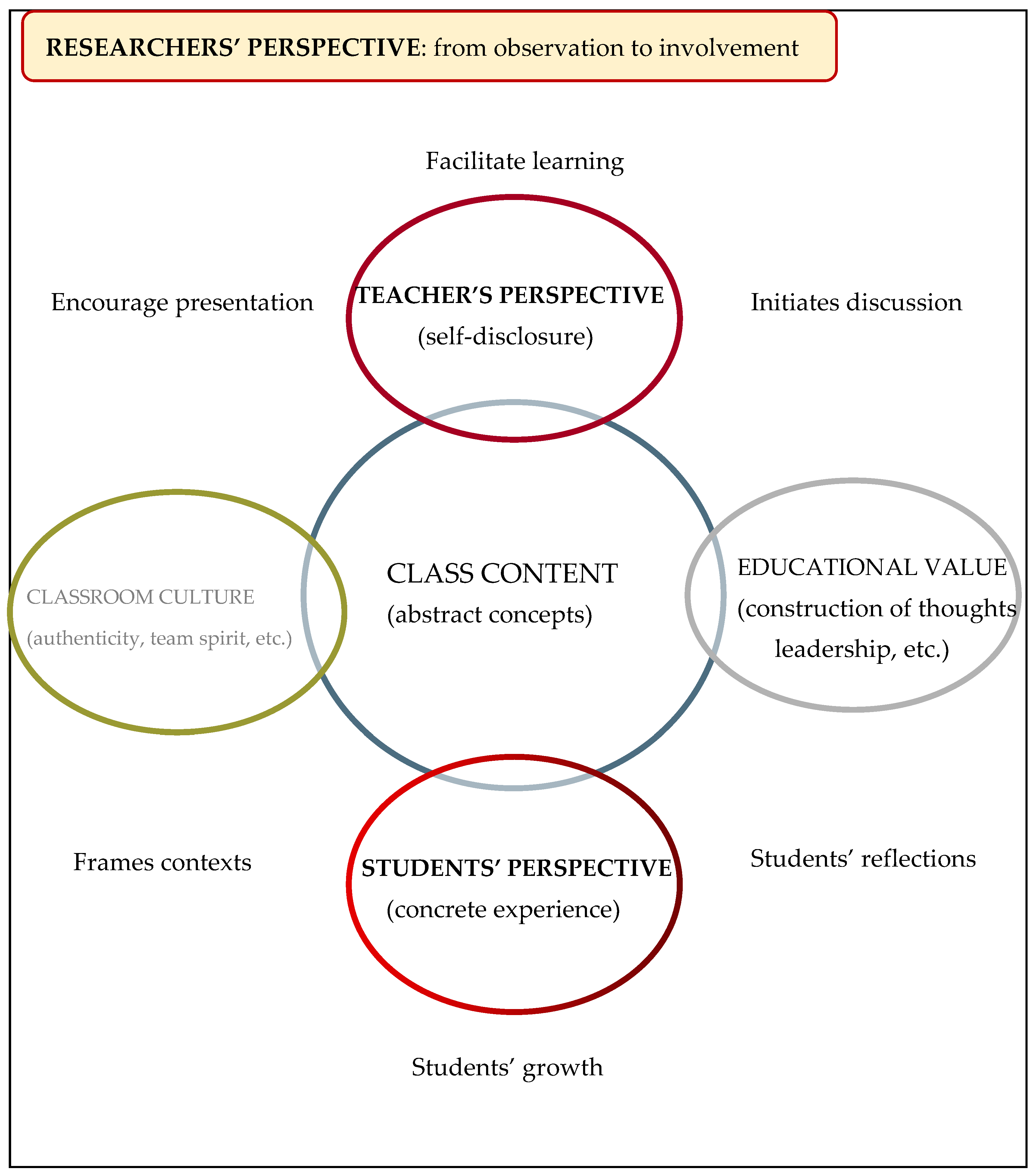

4.2. The Teacher’s Narrative of Classroom Culture

4.2.1. Cultural Narrative

4.2.2. Personal Narrative

4.3. Students’ Narrative of Growth

4.3.1. Episode Five: Paratexts—Improvement of Skills

4.3.2. Episode Six: From “Mad” to “Alive”—Growth from Failure

- Low Point

Huang: Yuan had prepared extensively. However, as soon as she started reading the first two lines, my heart sank. It was a rigid recitation, which is a taboo in class presentation. As expected, Yin pointed it out and asked us to make immediate revisions. I felt a big blow, thinking it was all over. I engaged in intense discussions with my classmates while quickly modifying the content I was going to present. I even wrote four words on the paper, “I’m going crazy.”

- Presenters’ interpretation—a great failure.

- 2.

- The teacher’s interpretation—frustration education.

- Turing Point

- 3.

- Presenters’ re-interpretation—smile.

Yuan: I wanted to show the teacher that we could do it. I was very nervous, and my speech was a bit disorganized, but I tried my best to make my classmates understand the key points through the use of the blackboard. At that moment, I saw Yin giving us his thumbs up. I felt a great relief and smiled. It was only then that I realized that this rollercoaster of ups and downs was yet another lesson on living through setbacks. I wrote down the words “I’m alive again.”

- 4.

- The teacher’s re-interpretation: Thumbs up.

Yin: I was thrilled when I witnessed your second presentation. What a miracle it was! Within just half an hour after a devastating defeat, you managed to make a triumphant comeback to the forefront. It’s truly unbelievable. This experience will strengthen my resolve and composure when I deliver another heavy blow to you in the future. I admire your ability to endure suffering with a courageous heart.

- High Point

- 5.

- Presenters’ interpretation: Growth.

Xiaoru: This classroom experience has been immensely beneficial to me. It goes beyond the mere label of “College English” and encompasses the valuable lessons I’ve learned in classroom presentations and overcoming challenges. The English class has witnessed my personal growth.

- 6.

- Other students’ interpretation: Responsibility.

Group Five: We bore witness to the growth journey of the fourth group as they faced challenges and overcame them. Creating an environment of continuous improvement in the classroom is not solely the teacher’s responsibility, but also the duty and privilege of students.

- 7.

- The teacher’s interpretation: Authentic classroom knowledge community witnessed students’ growth.

Yin: Read this report and you will feel a sense of pride. These students are truly remarkable, displaying genuine passion. I am filled with joy to have such exceptional young individuals as my students, witnessing their rapid growth right before my eyes, akin to bamboo shoots sprouting in the springtime.

- 8.

- The observer’s interpretation: Moved and want to be a teacher like Yin.

Xin: While reading the report, I was deeply moved by the heartfelt dialogs between the students and the teacher. This process proved to be immensely beneficial for me, fueling my passion and determination to become a teacher like Yin.

- Interpretive Aspects of Narrative

4.4. Summary

5. Conclusions

6. Final Thoughts

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A normal university in China means a teacher education university in the Chinese context. |

| 2 | WeChat, like Facebook, is a multi-purpose messaging, social media, and mobile payment app developed by the Chinese company Tencent. |

References

- Austin, T. (2020). Narrative environments and experience design: Space as a media of communication. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination. University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. (1987). Life as narrative. Social Research, 54, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafe, W. (1990). Some things that narrative tell us about mind. In B. K. Pellagrini, & A. D. Britton (Eds.), Narrative thought and narrative language. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C., & Sage, M. (2019). A narrative review of digital storytelling for social work practice. Journal of Social Work Practice, 35, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin, D. J., Huber, J., Huber, M., Murphy, M. S., Orr, A. M., Pearce, M., & Steeves, P. (2006). Composing diverse identities: Narrative inquiries into the interwoven lives of children and teachers. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C. (1995). Knowledge communities: A way of making sense of how beginning teachers come to know. Curriculum Inquiry, 25(2), 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C. (2004). Shifting boundaries on the professional knowledge landscape: When teacher communications become less safe. Curriculum Inquiry, 34(4), 395–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C. (2013). Life on school landscapes: Teachers’ experiences, relationships and emotions. In M. Newberry, A. Gallant, & P. Riley (Eds.), Emotion in schools: Understanding how the hidden curriculum influences relationship, leadership, teaching and learning (pp. 99–117). Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, C., Curtis, G., Kelley, M., Martindell, P. T., & Michael, M. (2020). Knowledge communities in teacher education: Sustaining collaborative work. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, C., Evans, P., Stokes, D., McAlister-Shields, L., & Curtis, G. A. (2024). Multi-layered mentoring: Exemplars from a US STEM teacher education program. Teachers and Teaching, 30, 241–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C., Williams, J., & Hill-Jackson, V. (2025). Dead spaces in teaching and teacher education: What are they? How can they be overcome? Journal of Teacher Education, 76(2), 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, G., Reid, D., Kelley, M., Martindell, P. T., & Craig, C. J. (2013). Braided Lives: Multiple ways of knowing, flowing in and out of knowledge communities. Studying Teacher Education, 9(2), 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Collier Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzy, D. (2002). Qualitative analysis: Practice and innovation. Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, H. G. (2004). Truth and method. China Social Sciences Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, H. (2001). Cognitive development and learning in instructional context. Ally & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, C. (1998). Langugage and culture. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lantolf, J. P. (2000). Sociocultural theory and second language learning. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lier, V. (2004). The ecology and semiotics of language learning: A social cultural perspective. Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, W. (2006). Recent theories of narrative. Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 74, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M., & Craig, C. J. (2001). Opportunities and challenges in the development of teachers’ knowledge: The development of narrative authority through knowledge communities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(6), 667–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V. (2023). A History of narrative environments. Available online: https://ribbonfarm.com (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Schein, E. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Schon, D. A. (1987, April 20–24). Educating the reflective practitioner. Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, J. J. (1969). College curriculum and student protest. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tom, A. R., & Valli, L. (Eds.). (1990). Professional knowledge for teachers in W.R. Houston. In Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 373–392). Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z. (2005). Teachers’ knowing in curriculum change: A critical discourse study of language teaching. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L., & Craig, C. (2020). A narrative inquiry into the cultivation of self and identity of three novice teachers in Chinese colleges—Through the evolution of an online knowledge community. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(5), 646–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class | Course | Learning Materials | Times | Students | Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Western Mythology | Western Culture in Mythology, edited by Yin | 17 weeks | 52 | 9 |

| Class 2 | Western Philosophy | Fifteen Lectures on Western Philosophy | 17 weeks | 52 | 9 |

| Class 3 | Advanced English | Philosophy of Self, edited by Yin | 17 weeks | 30 | 6 |

| Class | Teaching Journals | Graduates’ Observations | Students’ Notes | Students’ Reflections | Monthly Reports | Interviews with Teachers | Interviews with Students |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | 17 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 16 | 3 | 5 |

| Class 2 | 17 | 6 | 8 | 17 | 14 | 2 | 3 |

| Class 3 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 12 | 15 | 3 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, L.; Craig, C.J. A Narrative Inquiry into the Cultivation of a Classroom Knowledge Community in a Chinese Normal University. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070911

Zhong L, Craig CJ. A Narrative Inquiry into the Cultivation of a Classroom Knowledge Community in a Chinese Normal University. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070911

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Libo, and Cheryl J. Craig. 2025. "A Narrative Inquiry into the Cultivation of a Classroom Knowledge Community in a Chinese Normal University" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070911

APA StyleZhong, L., & Craig, C. J. (2025). A Narrative Inquiry into the Cultivation of a Classroom Knowledge Community in a Chinese Normal University. Education Sciences, 15(7), 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070911