Abstract

This narrative inquiry explores a vibrant classroom knowledge community in a Chinese normal university. By examining the teacher’s interactions, we analyze the community’s development through three perspectives: (1) the author’s narrative of the course outline, (2) the teacher’s narrative of classroom culture, and (3) students’ narratives of their growth. The author presents a student-centered model and seven steps for enacting the course, outlining the environment for cultivating the knowledge community. The teacher’s narrative reveals clues to his success, emphasizing his use of storytelling to foster the community and share educational ideas. Students’ narratives reflect their growth, validating the classroom as a safe space for development and language learning. The significance of this research is that the classroom knowledge community consisted of the teacher, his undergraduate students, and his post-graduates. The three layers existed because of this unrestrained character, devoid of conflicts of interest, created a safe place for students’ development. This research study adds to the literature on how knowledge communities form in school contexts. It focuses on a particular space and time and involves multiple layers of participants, which is prerequisite to the conceptualization of classroom knowledge community. This research has important implications for college language education.

1. Introduction

In Chinese universities, English language teaching has often been marginalized within the broader educational framework. It is commonly assumed that engaging with philosophical questions around worldview and values is unnecessary in language instruction. Students, particularly those majoring in foreign languages, are expected to speak and write with the fluency and articulation of native speakers. However, little attention is given to the content of their communication or the reasoning behind their conclusions. Instead, proficiency in the target language is often treated as a prerequisite for academic success. Language teachers tend to be less reflective about their pedagogical practices from a philosophical perspective compared to educators in other disciplines. This perception of neutrality in language teaching is misleading.

Recent scholarship has begun to challenge the notion that language teaching can be value-free. As Kramsch (1998) asserts, “language is not just a code for expressing thoughts, it is also a social practice that shapes identity and community.” Research indicates that students inevitably learn more than just linguistic skills in their language classes, they absorb values and attitudes from the texts they engage with and the discussions they participate in. Van Lier (2004) emphasizes that language learning is “a social process that involves the negotiation of meaning and identity.” Despite this recognition, the role of language teachers in shaping students’ academic and personal growth remains underexplored. Lantolf (2000) argues that “language learning is fundamentally an evaluative enterprise,” highlighting the importance of understanding the sociocultural contexts in which language is taught. Engaging with these theoretical frameworks underscores the critical point that language education cannot be separated from the values and ideologies embedded within it. It is crucial for language educators to recognize their responsibility in fostering students’ overall development. A language class should not only aim to develop linguistic skills but also to reflect the broader educational goals of the university. Therefore, understanding how to create a supportive and authentic learning environment is essential.

This study explores the cultivation of a “classroom knowledge community,” defined as an environment where learners and teachers can exchange ideas freely and safely. We employ “narrative inquiry,” which involves sharing and reflecting on personal experiences, to construct a curriculum that values authenticity and connection. Through the examination of one teacher Yin’s (pseudonym) classroom practices, this research aims to highlight the interplay between narrative, community, and educational growth. In this study, the classroom knowledge community included three layers of participants: the teacher, his undergraduates and his post-graduates (who acted as the researchers). In the case of the teacher’s actual classroom, we explore the cultivation of the classroom knowledge community from three narrative perspectives: (1) the first author’s narrative of the course outline/syllabus, (2) the teacher’s narrative of the classroom culture, and (3) the students’ narratives of their growth. First, the first author’s narrative presents a tripartite (Austin, 2020) student-centered model of course enactment and the seven steps of the course’s development. It provides the milieu in which the classroom knowledge community was cultivated. Second, the teacher’s narrative provides clues to the success of his class, through his creation of a narrative environment (Rao, 2023) for a classroom knowledge community and how educational ideas would be shared with students. Third, the students’ narrative of their growth is the ultimate purpose of the teacher’s education and occupation, and in return, is the best proof of the success of the classroom knowledge community as a “safe place” (Craig, 1995, 2004; Olson & Craig, 2001) for students’ growth, as well as for their language learning. By investigating the experiences of undergraduates and postgraduates within this knowledge community, the study aims to illustrate how a supportive classroom environment can facilitate linguistic proficiency, critical thinking, and interpersonal skills. The ultimate goal is to prepare students not only for academic success but also for personal fulfillment.

2. Conceptual Backdrop

2.1. Knowledge Community

The concept of knowledge communities, as developed by the author, builds upon the foundational work of Dewey (1938), Schwab (1969), Connelly and Clandinin (1990), and others. These communities are seen as essential spaces where teachers collaboratively develop their knowledge through shared experiences and narratives. Drawing from Wenger (1998) and Lave and Wenger (1991), knowledge communities are defined as social structures that facilitate the ongoing negotiation and reconstruction of knowledge among members.

Craig’s longitudinal research has demonstrated how teachers engage in storytelling and re-storying their experiences within these contexts, influenced by the nature of their school environments. Knowledge communities are described as “safe places” where teachers can openly discuss their practices, revisit, reassess, and re-story their experiences. These communities become particularly important when teachers face tensions in their professional lives, providing the support necessary for ongoing instruction and growth.

The notion of “safe spaces” is further supported by Mezirow (1997), who emphasizes the importance of creating environments where individuals feel secure enough to engage in critical reflection and transformative learning. Such spaces not only foster trust but also encourage deep interpersonal relationships, enabling members to reflect more profoundly than individual reflection would allow (Zhong & Craig, 2020). This aligns with Vygotsky’s (1978) idea that social interaction is crucial for cognitive development, reinforcing the significance of collaborative reflection in knowledge communities.

2.2. Teacher Knowledge Community

Teacher knowledge communities form around “an originating event” (Schein, 1985), creating a shared meaning among members. Within these communities, knowledge is continuously negotiated, allowing for dynamic evolution as individuals join or leave. Each member may belong to multiple knowledge communities simultaneously. The braided river metaphor employed by Curtis et al. (2013) effectively illustrates the fluid nature of knowledge as it flows in and out of these communities, reflecting the diverse ways of knowing that emerge as members interact.

It is essential to highlight the narrative aspect of teacher knowledge communities, which emphasizes how teachers’ experiences and stories contribute to the collective knowledge of the community. This narrative dimension captures the complexities of teacher identities and practices, further enriching the understanding of these communities.

2.3. Classroom Knowledge Community

Similarly to teachers, students also thrive within knowledge communities, particularly in the classroom setting. In this research, the classroom is viewed as a vital space for cultivating student knowledge communities. The teacher, researchers, and participating students constitute the core members of this community. The espoused theory posits that the combination of educational theory, collaboration, and reflection leads to improved teaching practices, which in turn benefits students.

Regular public reflection in a safe and nurturing environment allows students to engage in the zone of maximal contact, where their past, present, and future experiences converge. This interaction results in significant shifts in their thinking and actions (Zhong & Craig, 2020). Thus, classroom knowledge communities serve as safe spaces for students to learn, reflect, and grow, fostering a culture of inquiry and collaboration.

In contrast, “dead spaces” occur when imagination and connection are lacking, often filled with policies and procedures that alienate individuals from themselves and one another (Dewey, 1938). There is no place for one’s self and the ongoing reconstruction of one’s self in dead spaces—let alone spaces for the students one teaches (Craig et al., 2025). Classroom knowledge communities strive to overcome these limitations, creating vibrant environments for meaningful learning.

3. Research Method

3.1. Narrative Inquiry

Connelly and Clandinin’s (1990) narrative inquiry method was used. It traces back to Dewey’s (1938) experiential philosophy and Schwab’s (1969) practical scholarship. We explored research participant Yin and his students’ stories of experience in a three-dimensional narrative inquiry space (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000) involving the temporal, personal-social, and place. We present the background of the teacher’s educational reform and consequently the tripartite student-centered model of course enactment and seven steps of the course’s instantiation, which creates the milieu for the cultivation of the classroom knowledge community. As for the personal–social dimension, we observed multi-layered relationships among the teacher, the researchers, and the teacher’s former students and the current students, and focused on classroom culture transformation and current students’ challenges and growth in the knowledge community.

Why do we use narrative inquiry as our method?

First, we use narrative inquiry because we regard curriculum as the nourishment of teachers’ and students’ lives—human growth and self-fulfillment. The nourishment of teachers’ lives often subsequently contributes to the nourishment of students’ of lives. Narrative analysis focuses more directly on the dynamics the “in process” nature of interpretation (Ezzy, 2002). That is how the interpretation changes with time, new experience, and with new and varied social interactions. When a curriculum is understood as a dynamic interplay of multiple, ongoing, experiential narratives that are continually reconstructed over time through interactive situations, the value of narrative inquiry for examining stories of practice is apparent. Second, the complexity of narrative becomes apparent when it is understood that each of us is authoring his/her own life while at the same time being a character in lives authored by others. Narration sometimes may appear to be monologic, but its success in establishing identity will inevitably rely on dialog. Narrative identities are interwoven within the culture. This could be explained by Bakhtin’s notion of dialogism. The living utterances, having taken meaning and shape at a particular historical moment in a social specific environment… are woven by social–ideological consciousness around the given object of an utterance (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 276). This dialogic imperative ensures that there can be no speaking person’s own words, no purely personal meanings (Wu, 2005, p. 215). All utterances mix different consciousnesses, one’s own and others’ (ibid). Thus, the stories teachers and students tell illuminate their personal thoughts and actions while making sense of their relationships with others and their stance in the world (Bruner, 1987). Third, narrative inquiry is a quite different way from traditional positivism. The dominance of positivism in educational research (Tom & Valli, 1990) has led to a vast body of knowledge that “looks at” and “talks about” education from the solid high ground of theory (Schon, 1987). Students’ authentic life is often ignored. There have been many authorized theories telling students and teachers to do this and to do that to achieve education success. As a result, telling and living unauthorized stories becomes difficult because we think the stories will not be accepted. So, narrative research recognizes the importance of teachers’ and students’ lives in educational development according to their own perceptions of their lives.

3.2. Data Sources

After observing Yin’s classroom for three terms during 2022–2024 (Table 1), data were collected via participant observation, interviews, and extant data sources. Students’ presentations, notes, and reflections were transcribed from recordings and sent to participants for feedback. Participant observation notes were shared too (Table 2). Focus groups were conducted with 134 learners. Lengthy interviews were conducted with ten students. Other data included impromptu conversations, post-class evaluations, and talks at lunchtime.

Table 1.

Basic information of the courses and the three classes.

Table 2.

Data for the present study.

3.3. Four Interpretive Tools

All the field texts were transformed into interim research texts using narrative inquiry’s four interpretive tools: broadening, burrowing, storying and restorying (Connelly & Clandinin, 1990), and fictionalization (Clandinin et al., 2006). Broadening included the existing language teaching limitations, the origins of Yin’s educational research, and teaching practice. Burrowing allowed the tripartite model of the course implementation and seven steps of the course procedure to be clearly presented. Storying/re-storying captured the classroom knowledge community’s cultivation, and the challenges and growth of the students over time. Fictionalization allowed the researchers to subtly shift circumstances to protect participants’ identities when they became increasingly identifiable and their relationships with one another were potentially placed at risk (Craig, 2013). We used fictionalization to also conceal the students’ names and the university that our participants attended. We also used fictionalization so that the participants would not be able to easily identify each other.

3.4. Participants

Yin, consistent with Normal University1 tradition, teaches English and American literature to English majors who will become teachers. Seven years ago, he started his educational research on the perspective of a humanistic curriculum and put his idea into teaching practice. His intent is not simply to impart the knowledge of Western cultural backgrounds. Rather, his ultimate purpose is to liberate students from their previous ways of thinking about the lives and fortunes of others and to develop sympathy towards the world they inhabit. With constant improvement, Yin’s course on Western Mythology as a freshmen elective has become one of the most popular courses.

Xin is one of Yin’s graduate students and a program member. The classroom knowledge community, which includes Yin, his undergraduate students (who soon will be teachers), his other graduates, and Xin, frequently meet at a cafe or in the library after class to discuss their learning and exchange understandings. After nearly two years under Yin’s supervision, Xin gleaned knowledge about Yin’s life story and professional experience, resulting in a profound understanding of his educational ideas.

4. Cultivation of the Classroom Knowledge Community

This part provides a narrative account of the cultivation of the classroom knowledge community, focusing on the teacher and his students’ personal experiences. The philosophic assumption is that “the empiricist ontology is constructed by the category of experience” (Wu, 2005), and human experience is the starting point of any social science. A narrative account of the knowledge that emerged from the teacher and his students’ experience provides a solid base for our research. Three types of narrative were used: narratives of Yin’s way of teaching from the author’s point of view, narratives of Yin’s professional experience, and narratives of his students’ learning experience.

4.1. The Author’s Narrative of Course Enactment

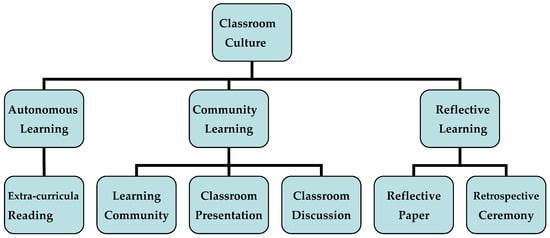

Yin’s course on Western Philosophy unfolds using a new way of teaching language in China. The class is organized as a seminar. Yin acts as the host, responsible for facilitating the discussion, while the students take charge of the entire process, deciding what topics to discuss and how to engage with them. Figure 1 presents a model for the course enactment. As foreshadowed, it is a tripartite model that integrates three views of language teaching: autonomous learning, community learning, and reflective learning. Seven steps address the three types of learning. This class puts students at the center of their learning, guided by the ultimate goal of their growth and self-fulfillment. This approach creates the milieu for the cultivation of the classroom knowledge community.

Figure 1.

The tripartite model of English teaching.

4.1.1. Classroom Culture: Authenticity

The first challenge encountered by innovative classes like Yin’s is how to establish an authentic classroom community culture. After over a decade of traditional education, most students have become accustomed to a teacher-centered approach and exhibit resistance and even hostility when they are encouraged to be more independent. This is when students need a teacher. The teacher’s objective in employing instructional techniques is “offering just enough assistance to guide the students toward independence and self-regulation” (Hartman, 2001). Narrative is the popular approach Yin utilizes to achieve this goal. Through story-telling, Yin creates a classroom community which leads his students to more easily understand and participate in his course.

4.1.2. Learning Community: Rotation of Roles

In the first class, a psychological questionnaire was used to allocate students into groups. Once the group division was completed, students were required to immediately relocate to their respective groups. For each unit, one group was assigned to prepare for a presentation, another group to take notes on the entire classroom proceedings, and a separate group to write a post-class reflection. The remaining groups served as active participants in the classroom discussion, engaging as questioners. Each group took turns to do each task.

4.1.3. Classroom Presentation: “Speak It Out”

In each class, Yin takes ten-twenty minutes to have a pre-class talk, providing feedback on students’ note-taking and reflection essays, offering encouragement for their efforts, and commenting on individuals or groups for their critical thinking or collaborative work. Afterward, Yin sits among his students and the presentation group assumes responsibility for leading the class. The main task is to present their understanding of the context in twenty minutes.

4.1.4. Classroom Discussion: “I Have a Question”

Afterwards, the presenters remain on the platform to ask or pose questions. If the students are unable to find suitable answers, group discussions within the classroom ensue. Class discussions are always driven by students’ questions. As they seek answers, new questions emerge, leading the discussion to delve deeper into the process of creating meaning.

4.1.5. Extra-Curricula Reading: “Go to the Library”

Although each group has different tasks, reading the textbook at least three times is required of everyone. In addition, extra-curricular reading is mandatory for fulfilling their respective tasks, which is an important part of a successful classroom performance and one of Yin’s expectations.

4.1.6. A Reflective Paper: “Think It Over”

After class, members of one group are expected to write a reflective essay centering on any perspective of the text that piques their interest. To ensure that every student has an equal opportunity to reflect on their learning, a monthly report appears. After a month’s learning, each group will look back on their experience and write a monthly reflection in terms of concrete knowledge learned, a response to how the content is being taught, etc.

4.1.7. A Retrospective Ceremony: Growth

Furthermore, in the final class, collective reflection on the entire term’s learning becomes the focal point. Students are encouraged to share their reflective opinions. Their attention is drawn to contingencies they encountered. This last class resembles a graduation ceremony, where each student recounts their learning along the way that contributed to their growth and development. The students’ classmates, the researchers, and Yin willingly serve as the audience.

4.1.8. Comments

So far, a brief overview of the enactment of Yin’s class from the author’s perspective has been introduced. The approach employs a tripartite model, integrating three views of language teaching into the context of an authentic classroom environment. The seven coherent processes belong to the three types of learning, respectively. To be exact, “extra-curricular reading” is autonomous learning; “learning community”, “classroom presentation” and “classroom discussion” are types of community learning; and “a reflective paper” and “a retrospective ceremony” are reflective learning. Compared with conventional lecturing, which involves question and answers between a teacher and students, this tripartite model is much more complicated and involves continuous live interactions between the teacher and students. Classrooms are “multi-layered” (Craig et al., 2024) environments with processes and dynamic social relationships that are embedded into the teaching and learning process. These environments “contain considerable complexity” and provide milieu around which the classroom knowledge community is cultivated. Confronted with the classroom complexity, a series of queries arise. For instance, how are authentic classroom environments formed? How might students be encouraged to make presentations? How can students’ passions be maintained during classroom questioning and discussion? In Yin’s classrooms, narratives, humor, and self-disclosure have been effective tools in helping his students to understand the material, in assisting him to create the classroom knowledge community, and in aiding his sharing of educational value with his students.

4.2. The Teacher’s Narrative of Classroom Culture

The focus of this section is to identify the use of stories and narratives as significant features of Yin’s course creation. An analysis of the data divides Yin’s classroom narratives into two categories: a cultural narrative and his personal narrative. Cultural narratives present the traditions of his course. Personal narratives assist to communicate his perspectives and educational values. Both occurred in the classroom knowledge community when current events, student issues, and personal perspectives were discussed.

4.2.1. Cultural Narrative

Narratives provide sources of cultural expression and the mind, not a record of the world, but rather a creation “according to its own mix of cultural and individual expectations” (Chafe, 1990, p. 81). This strengthens relationships and connections with others and establishes each individual’s place within the context of human interest. Here, we probe into Yin’s use of narrative for establishing connections between himself and students, fostering a shared interpretation of the world, and shaping the culture of the classroom knowledge community. Following are two stories Yin used to foster a classroom culture of team spirit and authenticity, respectively.

Episode one: Xiaojia’s tears—team spirit.

During the first term of the 2022–2023 school year, the senior students enrolled in Yin’s advanced English course. Xiaojia’s group worked hard and succeeded in note-taking and monthly reporting, which compensated for their lesser abilities where oral presentations were concerned. However, in the middle of the term, they were less committed to their study because of job-hunting. What is more, when it became time for Xiaojia’s group to present, they were faced with a difficult unit: The Alienation by Marx. When Xiaojia was to complete the ten-minute presentation, she surprised the whole class. ‘Silent, she stood on the platform, in tears, first with her face toward her classmates, then with her back toward them, and finally her face turned around again’. There was some anger among the students. But Yin was determined to let her stand through the required ten minutes. After ten minutes, Yin made a passionate speech, praising Xiaojia for her responsibility and courage. This class impressed every student because it taught a lesson about team spirit. Xiaojia reflected that she was sorry for her un-preparedness. Lihua, another group member who refused to do the presentation, cried in her seat, and blamed herself. She believed that if similar things happen in her future life, she would now undertake her duty and show her bravery. After this experience, the group became more united and faced all difficulties together. They made great progress in terms of academic knowledge and public speaking because of their renewed team spirit.

Yin regarded this story as a treasure. He even included the story in the book he compiled for the course. This made it possible for students to read the story and prepare for group work before class. Xiaojia’s story was told and retold. When students who take Yin’s class mention “Xiao Jia’s tears”, everyone knows it refers to the classroom culture of “teamwork”.

Episode two: Raise your hands—authenticity.

Authenticity is the basic and also the highest quality Yin calls for among his students. He believes that only when a person is authentic to themselves, to others, and to the world, can the language they use to communicate become meaningful and vibrant, and can their personal growth become possible. Also, only in an authentic classroom can a knowledge community be cultivated. This “raise your hands” story is another typical narrative of Yin’s classroom culture of authenticity, which has become a tradition to be passed on to his new students.

At the outset of the course on Western Philosophy, Yin asked his students to read the related unit three times before class. Furthermore, he checked their reading by asking them to raise their hands. As a result, 60 percent of the students read the unit only one time, 30 percent had read it three times, and 10 percent of the students raised their hands to admit that they hadn’t read the text at all. Yin praised those who read the work three times. Surprisingly, he also praised those 10 percent. Yin thanked them for their trust in him and their authenticity to themselves. In the following classes, most of the students tried to express their true feeling either in presentation or in discussion.

4.2.2. Personal Narrative

In the prior two sections, there are two stories of cultural narrative. Yin uses the story of his students’ experience to foster classroom culture. The subsequent stories are personal narratives that Yin shared to impart his educational values to his students. A student’s personal story of emerging as a leader and Yin’s self-disclosure of his learning journey convey his educational value regarding the importance of leadership in group work and the construction of thoughts in language learning.

Episode three: The emergent leader—leadership.

In the mid-term, Yin observed the presence of three distinct tiers of students in his Western Mythology course: the pioneers, the followers, and the wanderers. To aid the growth of the wanderers, Yin provided them with more opportunities for participation and established the role of an “emergent leader” within each group. The next day, in their note-taking file, one emergent leader stood out by writing her name in the designated space. Yin noticed that and made a phone call to Xin, serving as an observer of the classroom’s performance. He informed her to interview Wang and clarify what she had done. Xin contacted Wang by sending her WeChat2 messages and received Wang’s email, providing a detailed explanation of how she assumed the role of the emergent leader.

During the class opening in the following week, Yin highly praised Wang’s courage and invited her to share her reflections with her classmates. Wang received a round of spontaneous applause. Following that, each group engaged in negotiations among their members and selected the individual who needed more assistance to be the emergent leader. Ultimately, in their retrospective term papers, nearly every new leader noted that the experience of taking on a leadership role had greatly benefited them, fostering their rapid growth in terms of knowledge acquisition, critical thinking, and group management.

Episode four: Learning story—construction of thoughts.

Some students perceived Yin’s efforts to encourage them to discover a framework for the content and to engage in critical thinking as a waste of time. In her monthly reflection, Xiaolian confessed, “I had a strong dislike for his class … I engaged in reading philosophical books, disregarding his instruction.” Bruner (1987) writes that the “psychic reality” of the individual, in fact, may resist change. In Yin’s class, for instance, some students resisted additional changes even when such changes might have been very beneficial.

When Yin noticed, he believed that their eagerness to learn was a positive aspect. The only challenge was their lack of awareness regarding the significance of constructing thoughts in language acquisition. This is an ideological matter. Storytelling in non-judgmental ways helped Yin with the dilemma. He shared with them his own experience of learning English when he was their age.

I immersed myself in brilliant books, devouring them eagerly like a hungry man with bread in hand. I acquired a wealth of knowledge and became familiar with the works of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Lawrence, and others. However, I often pondered what else I gained from this endeavor. Does it hold any significance for my own thoughts and my life?

For his students, Yin’s self-disclosure through narrative was a process of coming to understand, in which the emphasis was on listening and receiving rather than on analysis, explanation, or categorization. Once the students accepted the story and engaged in self-reflection, the impact would be much greater than theoretical instruction. Xiaolian’s change in attitude and the subsequent outcomes serve as a perfect example. In her monthly reflection, she wrote:

The big change took place in this term. There were many factors interwoven together to cause my change, such as peer pressure, Yin’s care, etc. But the most important factor was Yin’s own story of his learning experience. After hearing his story, I began to reflect on mine. There is a famous Chinese saying: ‘the greatest sorrow of a nation is that every generation starts from zero’. Maybe, I should take Yin’s experience as a lesson and try to avoid the same mistake.

After Xiaolian decided to change, she became motivated and dedicated herself wholeheartedly to her studies. Her effort paid off, and she made remarkable progress. She confidently presented herself in question-and-answer formats, delivering clear and logical speeches that captivated the class.

In this period, one important thing aside from the interaction between the teacher and his students was the researchers involved in the course, who helped Yin gather information about his students. This made the classroom knowledge community multi-layered and added complexity and dynamics to the community.

4.3. Students’ Narrative of Growth

4.3.1. Episode Five: Paratexts—Improvement of Skills

In the freshmen Western Mythology course, Yin showed his students their predecessor’s successful use of pictures to tell mythological stories. Bearing this guidance in mind, students took the initiative to draw pictures on the blackboard before class. The presentation was attractive and triggered a consequent discussion filled with profound meaning making. In narratology, these pictures are called paratexts. “Narrative usually come packaged in additional words and sometimes even pictures…All of this tangential material can inflect our experience of the narrative … So in this sense all of this material is part of the narrative” (Martin, 2006). Pictures can make a complicated context simpler. However, with the increase in the difficulties of the text, pictures could no longer illustrate the meaning of the story. Group Nine attempted to use a concept map to create a framework of the central concepts in the unit. The concept map can also be considered a form of paratext and is an integral part of the students’ narrative. Group Nine’s successful creation of the concept map inspired other groups to express their understanding in their own ways. Some used multimedia to show the pictures clearer and more vividly; some found a video clip of Sisyphus rolling a rock up to the top of a mountain; others even role-played the dialog between Socrates and Euthydemus to illustrate Socrates’ “knowing the unknown”.

From pictures to the concept map, and from multimedia to video clips and role plays, the students used their own power of discourse to express their understanding of the contents. The power of narrative, in this case paratexts, lies in the close relevance to students’ life experience. “Digital narrative” (Chan & Sage, 2019) has received a great range of attention by capitalizing on the electronic capability to break up the text and incorporate into it pictures, graphics, and sound. Students are quick to learn new technologies, and to take the things with which they are familiar to the classroom and to improve their presentation skills.

4.3.2. Episode Six: From “Mad” to “Alive”—Growth from Failure

The students were freshmen in a Western Mythology course. Group Four survived a specific low point, a turning point, and high point of their experience, in which they called forth particular challenges in the eighty minutes of the two periods of classes. The girls now speak for themselves.

- Low Point

Huang: Yuan had prepared extensively. However, as soon as she started reading the first two lines, my heart sank. It was a rigid recitation, which is a taboo in class presentation. As expected, Yin pointed it out and asked us to make immediate revisions. I felt a big blow, thinking it was all over. I engaged in intense discussions with my classmates while quickly modifying the content I was going to present. I even wrote four words on the paper, “I’m going crazy.”

- Presenters’ interpretation—a great failure.

According to after-class interview, all members of the group regarded their presentation as a great failure.

- 2.

- The teacher’s interpretation—frustration education.

At first, Yin was satisfied with and highly praised the students’ activeness and initiative during the first three periods of their presentations. However, he became concerned about the negative consequence of the high-headed aura surrounding them and wanted them to experience frustration, for after reading their reflections, he had complete confidence in students’ ability to endure it.

- Turing Point

- 3.

- Presenters’ re-interpretation—smile.

Yin gave the presenters five minutes to re-organize their presentation and consciously guided them to re-present their ideas with the assistance of a concept map. After an on-the-spot group discussion, three presenters came to the chalkboard and drew some simple diagrams. But the second presenter still did not make use of the concept map. It was not until the third presenter, Yuan, had their turn and the class made a breakthrough.

Yuan: I wanted to show the teacher that we could do it. I was very nervous, and my speech was a bit disorganized, but I tried my best to make my classmates understand the key points through the use of the blackboard. At that moment, I saw Yin giving us his thumbs up. I felt a great relief and smiled. It was only then that I realized that this rollercoaster of ups and downs was yet another lesson on living through setbacks. I wrote down the words “I’m alive again.”

- 4.

- The teacher’s re-interpretation: Thumbs up.

Yin: I was thrilled when I witnessed your second presentation. What a miracle it was! Within just half an hour after a devastating defeat, you managed to make a triumphant comeback to the forefront. It’s truly unbelievable. This experience will strengthen my resolve and composure when I deliver another heavy blow to you in the future. I admire your ability to endure suffering with a courageous heart.

- High Point

- 5.

- Presenters’ interpretation: Growth.

Xiaoru: This classroom experience has been immensely beneficial to me. It goes beyond the mere label of “College English” and encompasses the valuable lessons I’ve learned in classroom presentations and overcoming challenges. The English class has witnessed my personal growth.

- 6.

- Other students’ interpretation: Responsibility.

The growth exhibited by Group Four prompted the following reflection from the note-taking group.

Group Five: We bore witness to the growth journey of the fourth group as they faced challenges and overcame them. Creating an environment of continuous improvement in the classroom is not solely the teacher’s responsibility, but also the duty and privilege of students.

They even regarded the improvement in the class performance as their own duty and responsibility.

- 7.

- The teacher’s interpretation: Authentic classroom knowledge community witnessed students’ growth.

Yin: Read this report and you will feel a sense of pride. These students are truly remarkable, displaying genuine passion. I am filled with joy to have such exceptional young individuals as my students, witnessing their rapid growth right before my eyes, akin to bamboo shoots sprouting in the springtime.

- 8.

- The observer’s interpretation: Moved and want to be a teacher like Yin.

Xin: While reading the report, I was deeply moved by the heartfelt dialogs between the students and the teacher. This process proved to be immensely beneficial for me, fueling my passion and determination to become a teacher like Yin.

- Interpretive Aspects of Narrative

A narrative approach to human development is fundamentally interpretive. Life stories, much like literary narratives, consist of elements that are both discovered and constructed. Consequently, when we seek to comprehend the actions of others, we should approach them as literary interpreters and hermeneuticists, treating their actions as texts that hold potential meanings. In this “mad and alive” narrative, Group Four’ s presentation itself unfolded as an original story. Faced with the same narrative, individuals held different perspectives. The girls in the presentation group perceived it as a failure, as their delivery method involved simply reading the material, resulting in a lack of engagement and failing to capture the attention of others. Yin provided a critique of their performance because he observed a sense of pride and arrogance in the class, and he aimed to impart a lesson of frustration. By explaining his intention to challenge them and emphasizing the prerequisite of believing in their ability to endure hardship, Yin broadened the horizons of the presenters. Upon realizing that the teacher’s strictness was aimed at fostering their growth through failure rather than assigning blame, the presenters smiled and embraced this newfound awareness. With this expanded perspective, they diligently worked on the spot and re-presented the material using a fresh framework of central concepts. Yin’s gesture of approval, a thumbs-up, signaled their success, and they themselves re-evaluated the entire process as a remarkable journey of personal growth. What is more, the conversation and interpretation to the second presentation influenced the other students and made them change in their horizon. The note-taking group, when organizing the classroom performance after class, thought reflectively that it was also each student’s responsibility to improve the classroom performance. The students’ reflections also had an impact on the teacher, reinforcing his determination to foster an authentic classroom knowledge community with the ultimate goal of student growth. These various interpretations even touched the classroom observer, inspiring a desire to become a teacher like Yin.

All of the new things we experience or learn help us to expand our horizons yet again, which then makes it easier to learn and experience even more new things. In order to have a “fusion of horizons” (Gadamer, 2004) and particularly to have our horizon expanded, we must stay open to whatever experience we are having. As a result, the narrative becomes a dynamic one. In this process, students learn from each other and experience sadness or happiness when they fail or succeed, which leads them to the utmost goal of growth.

4.4. Summary

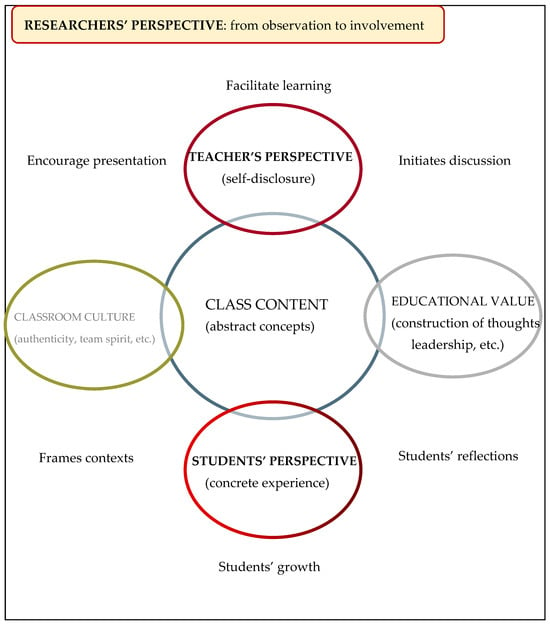

Figure 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the development of the classroom knowledge community. Initially, the researchers begin as observers of the class, documenting their observations and reflections on classroom activities. As they engage with the environment, their role evolves from passive observers to active participants in the learning process. This transformation allows them to provide deeper insights and interpretations of classroom dynamics.

Figure 2.

The cultivation of classroom knowledge community.

The researchers’ observations are discussed with the teacher and shared with the students, contributing to the dynamic and multi-perspective nature of the classroom knowledge community. This interpretive layering enriches the dialog among all participants, fostering a collaborative atmosphere where diverse viewpoints are valued.

The teacher employs narrative techniques to cultivate the classroom culture and impart educational values to the students. By encouraging presentations and initiating discussions, the teacher facilitates the students’ learning process. This approach not only supports the students in storytelling but also encourages them to frame various contexts based on their own understanding, contrasting abstract concepts with concrete experiences.

As students reflect on their learning journeys, they gain insights into their future professions, contributing to their personal and professional development. The harmonious interplay among the three layers of participants—teacher, researchers, and students—creates a safe and nurturing environment that fosters growth and development, particularly for the students.

In summary, the evolving role of the researchers, coupled with interpretive layering, enhances the richness of the classroom knowledge community, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the educational experience.

5. Conclusions

In this research study, we aimed to present the process of cultivating a classroom knowledge community. From the researchers’ perspective, we introduced a novel approach to language teaching and learning through a narrative inquiry into Yin’s classroom practices. This approach employs a tripartite model that integrates autonomous learning, communicative learning, and reflective learning within the classroom environment. This model not only fosters the development of the classroom knowledge community but also highlights the dynamic interactions that characterize it. The lead researcher’s role evolved from a mere observer of classroom performance to that of an active participant in class activities, contributing to the richness and diversity of perspectives within the knowledge community.

From the teacher’s perspective, we explored the factors contributing to the success of this classroom knowledge community, particularly the use of narrative in the classroom context. Yin’s teaching style, which combines storytelling and narrative with course enactment, creates an authentic culture that prepares students for advanced critical thinking and encourages emotional expression. He employs culturally appropriate strategies to foster interdependent development, integrating multiple representations of classroom culture such as team spirit and authenticity. The use of personal narratives and self-disclosure allows the teacher to share his viewpoints and educational values, thereby enhancing students’ awareness of their teacher’s cognitive and emotional processes.

From the students’ perspective, the establishment of a safe and nurturing learning environment nourishes not only the teacher and researchers but also the students themselves, facilitating human growth and self-fulfillment. The case study of students’ narratives reveals improvements in presentation skills, thought construction in language learning, and shifts in their perceptions of language teaching. This exploration of students’ lived experiences highlights the “fusion of horizons” as an innovative approach to understanding the dynamic, ongoing nature of interpretation in students’ lives.

When the classroom knowledge community is viewed as a dynamic interplay of multiple, experiential narratives that are continually reconstructed through interactive situations, the value of narrative inquiry in examining stories of practice becomes clear. This community serves as a context for critical dialog, where language conveys students’ authentic feelings and thoughts, making the learning experience vibrant and alive. Students are encouraged to delve beneath the surface of the text to understand the underlying ideologies, social and historical contexts, and personal implications, ultimately fostering their academic understanding and personal development.

Overall, this study extends the theoretical contributions of narrative inquiry by emphasizing its role in facilitating transformative learning experiences within classroom knowledge communities. By synthesizing findings across participant perspectives, we underscore the classroom knowledge community as a vital site of transformation, where collaborative dialog and shared narratives drive both individual and collective growth.

6. Final Thoughts

We now return to the problems we initially introduced. First, we address the implications of the research for classroom language education. The findings of this narrative inquiry into the cultivation of a classroom knowledge community in a Chinese normal university context reveal significant insights into the dynamics of classroom language education. By examining the experiences of the teacher, the first author, and the students, we can interpret the results in relation to the existing literature and explore their broader implications.

First, the tripartite model of course enactment highlighted in the study aligns with the principles of student-centered learning, emphasizing autonomy, community, and reflection. This model resonates with Dewey’s (1938) emphasis on experiential learning, suggesting that when students engage actively in their education, they are more likely to develop critical thinking skills and a deeper understanding of content.

Second, the narratives shared by the teacher and students illuminate how storytelling serves as a powerful tool in fostering a supportive classroom culture. This finding supports Craig et al. (2020) notion of knowledge communities as “safe places”, where dialog and reflection can occur freely. The emotional connections forged through narratives not only enhance student engagement but also promote a sense of belonging within the classroom knowledge community.

Third, the implications of this study extend beyond the specific context of a normal university in China. As educational institutions worldwide grapple with the challenges of fostering meaningful learning environments, the insights gained from this research can inform teaching practices in diverse settings. The emphasis on creating an authentic classroom knowledge community, where students feel safe to express themselves, is crucial for language education, particularly in cultures that may prioritize rote learning over critical engagement. Moreover, the role of the teacher as a facilitator rather than a mere transmitter of knowledge is vital for nurturing student growth. This shifts the focus from traditional pedagogical approaches to more collaborative and interactive methods, encouraging educators to reflect on their practices and foster environments conducive to student empowerment.

While this study provides valuable insights, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations. The findings are based on a single context, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Future research could explore the applicability of the tripartite model in different cultural and educational settings, as well as investigate the long-term impacts of cultivating a classroom knowledge community on students’ academic and personal development. Additionally, including perspectives from other stakeholders, such as former students or colleagues, could provide a more nuanced understanding of classroom dynamics and highlight discrepancies in reported experiences.

In conclusion, this narrative inquiry contributes to the literature on knowledge communities in education and emphasizes the transformative potential of authentic, narrative-rich pedagogy. By fostering reflective and empowered learners within collaborative knowledge communities, educators can create meaningful learning experiences that resonate deeply with students. The findings underscore the importance of narrative in language learning, highlighting how storytelling can enrich educational practices and cultivate engaged, thoughtful learners.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.J.C. and L.Z.; methodology, C.J.C. and L.Z.; software, L.Z.; validation, L.Z.; formal analysis, L.Z.; investigation, L.Z.; resources, L.Z.; data curation, L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.J.C.; visualization, L.Z.; supervision, C.J.C.; project administration, L.Z.; funding acquisition, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was sponsored by “Chinese Foreign Language Education Fund” project titled “Narrative Inquiry into the Tripartite Course Model in College English Teaching”, Project number: ZGWYJYJJ11A144.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai University of Medicine and Health Science (protocol code 2025-ESCI-12-001 and 25 June 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully appreciate the community members who willingly shared their experiences in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

| 1 | A normal university in China means a teacher education university in the Chinese context. |

| 2 | WeChat, like Facebook, is a multi-purpose messaging, social media, and mobile payment app developed by the Chinese company Tencent. |

References

- Austin, T. (2020). Narrative environments and experience design: Space as a media of communication. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination. University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. (1987). Life as narrative. Social Research, 54, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafe, W. (1990). Some things that narrative tell us about mind. In B. K. Pellagrini, & A. D. Britton (Eds.), Narrative thought and narrative language. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C., & Sage, M. (2019). A narrative review of digital storytelling for social work practice. Journal of Social Work Practice, 35, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin, D. J., Huber, J., Huber, M., Murphy, M. S., Orr, A. M., Pearce, M., & Steeves, P. (2006). Composing diverse identities: Narrative inquiries into the interwoven lives of children and teachers. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C. (1995). Knowledge communities: A way of making sense of how beginning teachers come to know. Curriculum Inquiry, 25(2), 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C. (2004). Shifting boundaries on the professional knowledge landscape: When teacher communications become less safe. Curriculum Inquiry, 34(4), 395–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C. (2013). Life on school landscapes: Teachers’ experiences, relationships and emotions. In M. Newberry, A. Gallant, & P. Riley (Eds.), Emotion in schools: Understanding how the hidden curriculum influences relationship, leadership, teaching and learning (pp. 99–117). Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, C., Curtis, G., Kelley, M., Martindell, P. T., & Michael, M. (2020). Knowledge communities in teacher education: Sustaining collaborative work. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, C., Evans, P., Stokes, D., McAlister-Shields, L., & Curtis, G. A. (2024). Multi-layered mentoring: Exemplars from a US STEM teacher education program. Teachers and Teaching, 30, 241–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C., Williams, J., & Hill-Jackson, V. (2025). Dead spaces in teaching and teacher education: What are they? How can they be overcome? Journal of Teacher Education, 76(2), 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, G., Reid, D., Kelley, M., Martindell, P. T., & Craig, C. J. (2013). Braided Lives: Multiple ways of knowing, flowing in and out of knowledge communities. Studying Teacher Education, 9(2), 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Collier Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzy, D. (2002). Qualitative analysis: Practice and innovation. Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, H. G. (2004). Truth and method. China Social Sciences Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, H. (2001). Cognitive development and learning in instructional context. Ally & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, C. (1998). Langugage and culture. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lantolf, J. P. (2000). Sociocultural theory and second language learning. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lier, V. (2004). The ecology and semiotics of language learning: A social cultural perspective. Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, W. (2006). Recent theories of narrative. Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 74, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M., & Craig, C. J. (2001). Opportunities and challenges in the development of teachers’ knowledge: The development of narrative authority through knowledge communities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(6), 667–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V. (2023). A History of narrative environments. Available online: https://ribbonfarm.com (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Schein, E. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Schon, D. A. (1987, April 20–24). Educating the reflective practitioner. Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, J. J. (1969). College curriculum and student protest. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tom, A. R., & Valli, L. (Eds.). (1990). Professional knowledge for teachers in W.R. Houston. In Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 373–392). Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z. (2005). Teachers’ knowing in curriculum change: A critical discourse study of language teaching. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L., & Craig, C. (2020). A narrative inquiry into the cultivation of self and identity of three novice teachers in Chinese colleges—Through the evolution of an online knowledge community. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(5), 646–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).