Characteristics of the Physical Literacy of Preschool Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Elements of Physical Literacy and Their Manifestations in the Initial Preschool Stage

3.2. Elements of Physical Literacy and Their Manifestations in the Elementary Preschool Stage

3.2.1. Manifestations of the Affective Domain

3.2.2. Manifestations of the Physical Domain

Basic Movement Skills

Postural Stability Skills

Locomotor Skills

Object Control Skills

3.2.3. Manifestations of the Cognitive Domain

3.2.4. Manifestations of the Social Domain

3.3. Elements of Physical Literacy and Their Manifestations in the Mature Preschool Stage

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of the Affective Domain of a Preschool Child

Factors Influencing Affective Domain

4.2. Characteristics of the Physical Domain of a Preschool Child

4.2.1. Factors Influencing Movement Skills

4.2.2. Characteristics of the Postural Stability Skills

4.2.3. Factors Influencing Postural Stability Skills

4.2.4. Characteristics of the Locomotor Skills

4.2.5. Factors Influencing Locomotor Skills

4.2.6. Characteristics of the Object Control Skills

4.2.7. Factors Influencing Object Control Skills

4.3. Characteristics of the Cognitive Domain of Preschool Children

4.4. Characteristics of the Social Domain of a Preschool Child

Factors Influencing Social Domain

4.5. Future Research Directions

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APLF | Australian Framework of Physical Literacy |

| TGMD-2 | Test of Gross Motor Development Second Edition |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings, National Library of Medicine (NLM), PubMed. |

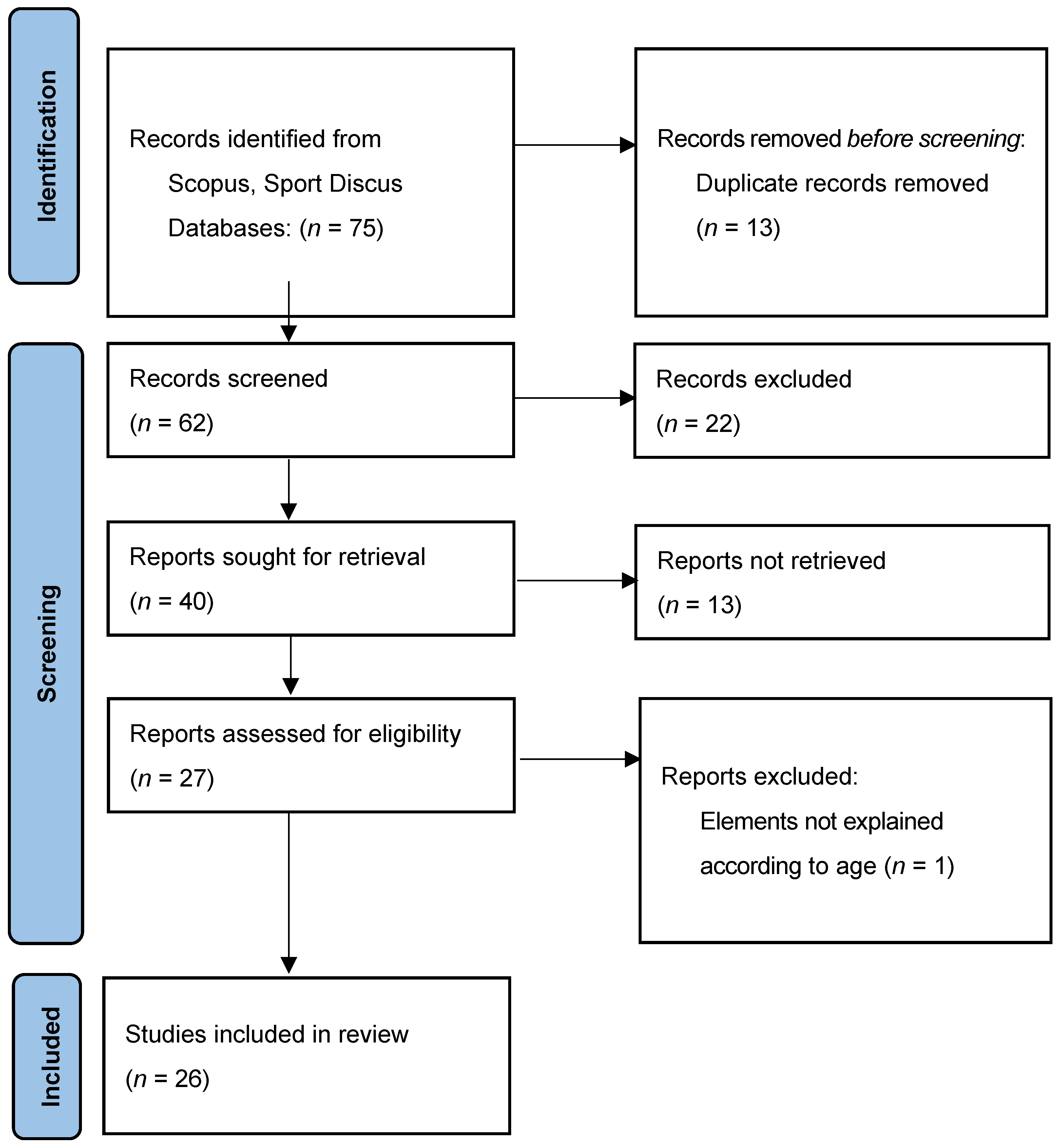

Appendix A. A Flow Map of the Review

References

- Almond, L. (2013). Physical literacy and fundamental movement skills: An introductory critique. ICSSPE Bulletin–Journal of Sport Science and Physical Education, 65, 81–88. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280715708_Physical_Literacy_and_Fundamental_Movement_Skills_an_Introductory_critique (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Bai, M., Lin, N., Yu, J. J., Teng, Z., & Xu, M. (2024). The effect of planned active play on the fundamental movement skills of preschool children. Human Movement Science, 96, 103241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, L. M., Mazzoli, E., Hawkins, M., Lander, N., Lubans, D. R., Caldwell, S., Comis, P., Keegan, R. J., Cairney, J., Dudley, D., Stewart, R. L., Long, G., Schranz, N., Brown, T. D., & Salmon, J. (2022). Development of a self-report scale to assess children’s perceived physical literacy. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27(1), 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, J., Dudley, D., Stylianou, M., & Cairney, J. (2024). A conceptual model of an effective early childhood physical literacy pedagogue. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 22(3), 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, T. A., Bandeira, P. F. R., de Souza Filho, A. N., Mota, J. A. P. S., Duncan, M. J., & de Lucena Martins, C. P. (2021). A network perspective on the relationship between moderate to vigorous physical activity and fundamental motor skills in early childhood. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 18(7), 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. In Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health (Vol. 11, Issue 4, pp. 589–597). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, Ú., Belton, S., Peers, C., Issartel, J., Goss, H., Roantree, M., & Behan, S. (2023). Physical literacy in children: Exploring the construct validity of a multidimensional physical literacy construct. European Physical Education Review, 29(2), 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairney, J., Clark, H., Dudley, D., & Kriellaars, D. (2019). Physical literacy in children and youth-a construct validation study. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 38(2), 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, H. A. T., Proudfoot, N. A., DiCristofaro, N. A., Cairney, J., Bray, S. R., & Timmons, B. W. (2022). Preschool to school-age physical activity trajectories and school-age physical literacy: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 19(4), 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, J., Jaunig, J., Kurtzhals, M., Müllertz, A. L. O., Stage, A., Bentsen, P., & Elsborg, P. (2023). Synthesising physical literacy research for ‘blank spots’: A Systematic review of reviews. Journal of Sports Sciences, 41(11), 1056–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durden-Myers, E. J. (2024). Advancing physical literacy research in children. Children, 11(6), 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durden-Myers, E. J., Bartle, G., Whitehead, M. E., & Dhillon, K. K. (2022). Exploring the notion of literacy within physical literacy: A discussion paper. In Frontiers in sports and active living (Vol. 4). Frontiers Media S.A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, L. C., Bryant, A., Keegan, R., Morgan, K., Cooper, S., & Jones, A. (2017). ‘Measuring’ physical literacy and related constructs: A systematic review of empirical findings. Sports Medicine, 48(3), 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezeugwu, V. E., Mandhane, P. J., Hammam, N., Brook, J. R., Tamana, S. K., Hunter, S., Chikuma, J., Lefebvre, D. L., Azad, M. B., Moraes, T. J., Subbarao, P., Becker, A. B., Turvey, S. E., Rosu, A., Sears, M. R., & Carson, V. (2021). Influence of neighborhood characteristics and weather on movement behaviors at age 3 and 5 years in a longitudinal birth cohort. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 18(5), 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friskawati, G. F. (2024). Teacher’s understanding of early childhood physical literacy: Thematic analysis based on teaching experience from an Indonesian perspective. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallahue, D. L., Ozmund, J. C., & Goodway, J. D. (2012). Understanding motor development: Infants, children, adolescents, adults (7th ed.). McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, M., & Fraser-Thomas, J. (2023). Describing early years sport: Take-up, pathways, and engagement patterns amongst preschoolers in a major Canadian city. Sport in Society, 27(1), 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, M., Roonasi, A., Saboonchi, R., & Salehian, M. H. (2012). Effect of selected physical activities on social skills among 3–6 years old children. Life Science Journal, 9(4), 4267–4271. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/88884945 (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Houser, N., & Kriellaars, D. (2023). “Where was this when I was in physical education?” Physical literacy enriched pedagogy in a quality physical education context. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, 1185680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iivonen, S., & Sääkslahti, A. (2014). Preschool children’s fundamental motor skills: A review of significant determinants. Early Child Development and Care, 184(7), 1107–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, R. J., Barnett, L. M., Dudley, D. A., Telford, R. D., Lubans, D. R., Bryant, A. S., Roberts, W. M., Morgan, P. J., Schranz, N. K., Weissensteiner, J. R., Vella, S. A., Salmon, J., Ziviani, J., Okely, A. D., Wainwright, N., & Evans, J. R. (2019). Defining physical literacy for application in Australia: A modified Delphi method. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 38(2), 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretaine, A., & Vecenane, H. (2024). Assessing physical literacy of pre-school children—A systematic literature review. Education Innovation Diversity, 1(8), 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahuerta-Contell, S., Molina-García, J., Queralt, A., Bernabé-Villodre, M. d. M., & Martínez-Bello, V. E. (2021). Ecological correlates of Spanish preschoolers’ physical activity and sedentary behaviours during structured movement sessions. European Physical Education Review, 27(3), 636–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre-Román, P. A., Martínez-Redondo, M., Párraga-Montilla, J. A., Lucena-Zurita, M., Manjón-Pozas, D., González, P. J. C., Robles-Fuentes, A., Cardona-Linares, A. J., Keating, C. J., & Salas-Sánchez, J. (2021). Analysis of dynamic balance in preschool children through the balance beam test: A cross-sectional study providing reference values. Gait and Posture, 83, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, A. R., Coughenour, C., Case, L., Bevell, J., Fryer, V., & Brian, A. (2022). A review of motor skill development in state-level early learning standards for preschoolers in the United States. Journal of Motor Learning and Development, 10(3), 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, S. W., Ross, S. M., Chee, K., Stodden, D. F., & Robinson, L. E. (2018). Fundamental motor skills: A systematic review of terminology. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(7), 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ltifi, M. A., Turki, O., Ben-Bouzaiene, G., Chong, K. H., Okely, A. D., & Chelly, M. S. (2024). Exploring urban-rural differences in 24-h movement behaviours among Tunisian preschoolers: Insights from the SUNRISE study. Sports Medicine and Health Science, 7(1), 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugossy, A.-M., Froehlich Chow, A., & Humbert, M. L. (2022). Learn to do by doing and observing: Exploring early childhood educators’ personal behaviours as a mechanism for developing physical literacy among preschool aged children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(3), 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, T. C. T., Chan, D. K. C., & Capio, C. M. (2021). Strategies for teachers to promote physical activity in early childhood education settings—A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnejja, K., Fendri, T., Chaari, F., Harrabi, M. A., & Sahli, S. (2022). Reference values of postural balance in preschoolers: Age and gender differences for 4–5 years old Tunisian children. Gait & Posture, 91, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Patón, R., Canosa-Pasantes, F., Mecías-Calvo, M., & Arufe-Giráldez, V. (2024). Modification of the relative age effect on 4–6-year-old schoolchildren’s motor competence after an intervention with balance bike. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 19(3), 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelemiš, V., Pavlović, S., Mandić, D., Radaković, M., Branković, D., Živanović, V., Milić, Z., & Bajrić, S. (2024). Differences and relationship between body composition and motor coordination in children aged 6–7 years. Sports, 12(6), 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J. E., Dabkowski, E., Prokopiv, V., Missen, K., Barbagallo, M., & James, M. (2023). An exploration into early childhood physical literacy programs: A systematic literature review. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 48(1), 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiola, G. (2025). Physical literacy, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), in an Italian preschool and education for a daily movement routine. Children, 12(1), 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R. E., Guerrero, M. D., Vanderloo, L. M., Barbeau, K., Birken, C. S., Chaput, J.-P., Faulkner, G., Janssen, I., Madigan, S., Mâsse, L. C., McHugh, T.-L., Perdew, M., Stone, K., Shelley, J., Spinks, N., Tamminen, K. A., Tomasone, J. R., Ward, H., Welsh, F., & Tremblay, M. S. (2020). Development of a consensus statement on the role of the family in the physical activity, sedentary, and sleep behaviours of children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico-González, M., Ardigò, L. P., Ramírez-Arroyo, A. P., & Gómez-Carmona, C. D. (2024). Anthropometric influence on preschool children’s physical fitness and motor skills: A systematic review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 9(2), 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd, J. R., Barnett, L. M., Butson, M. L., Farrow, D., Berry, J., & Polman, R. C. J. (2015). Fundamental movement skills are more than run, throw and catch: The role of stability skills. PLoS ONE, 10(10), e0140224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, S. K., Sheikh, M., & Talebrokni, F. S. (2017). Comparison exam of Gallahue’s hourglass model and Clark and Metcalfe’s the mountain of motor development metaphor. Advances in Physical Education, 7(3), 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F., Newman, T. J., Aytur, S., & Farias, C. (2022). Aligning physical literacy with critical positive youth development and student-centered pedagogy: Implications for today’s youth. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4, 845827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, H., Nomura, Y., & Kamide, K. (2022). Relationship between static balance and gait parameters in preschool children. Gait & Posture, 96, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stania, M., Sarat-Spek, A., Blacha, T., Kazek, B., Juras, A., Słomka, K. J., Juras, G., & Emich-Widera, E. (2024). Rambling-trembling analysis of postural control in children aged 3–6 years diagnosed with developmental delay during infancy. Gait & Posture, 82(2020), 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starrett, A., Pennell, A., Irvin, M. J., Taunton Miedema, S., Howard-Smith, C., Goodway, J. D., Stodden, D. F., & Brian, A. (2021). An examination of motor competence profiles in preschool children: A latent profile analysis. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 93(3), 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaidou, C., Konstantinidou, E., & Venetsanou, F. (2021). Effects of an eight-week creative dance and movement program on motor creativity and motor competence of preschoolers. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 21(6), 3268–3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, B. W., Naylor, P.-J., & Pfeiffer, K. A. (2007). Physical activity in preschool age children—Amount and method? Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 32(Suppl. 2F), S139–S149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M. S., Chaput, J.-P., Adamo, K. B., Aubert, S., Barnes, J. D., Choquette, L., Duggan, M., Faulkner, G., Goldfield, G. S., Gray, C. E., Gruber, R., Janson, K., Janssen, I., Janssen, X., Jaramillo Garcia, A., Kuzik, N., LeBlanc, C., MacLean, J., Okely, A. D., … Carson, V. (2017). Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for the early years (0–4 years): An integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. BMC Public Health, 17(Suppl. 5), 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trost, S., Schipperijn, J., Nathan, A., Wolfenden, L., Yoong, S., Shilton, T., & Christian, H. (2024). Population-referenced percentiles for total movement and energetic play at early childhood education and care. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 27(12), 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Užičanin, E., Gilić, B., Babajic, F., Huremovic, T., Hodzic, S., Bilalic, J., & Sajber, D. (2024). The international study of movement behaviours in the early years: A pilot study from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Montenegrin Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 13(2), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtíková, L., Hnízdil, J., Turčová, I., & Wojciech, S. (2023). The relationship of cognitive abilities and motor proficiency in preschool children—Pilot study. Physical Activity Review, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, S., Bratić, M., & Vukajlović, N. Z. (2023). The effects of a sports school program on motor skills in preschool children. Physical Education and Sport, 21(2), 121–128. Available online: https://casopisi.junis.ni.ac.rs/index.php/FUPhysEdSport/article/view/12129 (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Wainwright, N., Goodway, J., John, A., Thomas, K., Piper, K., Williams, K., & Gardener, D. (2020). Developing children’s motor skills in the foundation phase in Wales to support physical literacy. Education 3-13, 48(5), 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, N., Goodway, J., Whitehead, M., Williams, A., & Kirk, D. (2018). Laying the foundations for physical literacy in Wales: The contribution of the Foundation Phase to the development of physical literacy. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(4), 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, M. (2010). Physical literacy: Throughout the lifecourse. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, M. (2019). Physical literacy across the world. Routledge eBooks. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2019). Guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age. World Health Organization. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311664 (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Yürük, S., Sönmez, S., & Kazak, F. Z. (2024). Values development through gymnastic education in preschool children. Science of Gymnastics Journal, 16(1), 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domains | Elements of Physical Literacy (Whitehead, 2019) | Manifestations in Behaviour | Summary: Modalities and Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective | Motivation | Mentioned, but not explained (Caldwell et al., 2022) | - |

| Confidence | Mentioned, but not explained (Caldwell et al., 2022) | - | |

| Physical | Basic movement skills | Basic fine and gross motor skills may depend on the child’s height (Rico-González et al., 2024) | Influencing factors: Height |

| Locomotor skills | Running (Caldwell et al., 2022; Lindsay et al., 2022), Jumping, walking, climbing, hopping (unspecified), galloping, climbing up and down, skipping, dancing, hopping on one foot, marching, gliding (Lindsay et al., 2022) | Locomotor types: Running, Jumps: jumps on spot, jumps in different directions horizontally, jumps in different ways (styles), walking, moving up and down stairs, Dancing | |

| Object control skills | Throwing, pushing, catching the ball. Use of outdoor gaming equipment (Lindsay et al., 2022), Object control skills—upper and lower body parts (Caldwell et al., 2022) | Modalities of object control: Ball control skills: Throwing, pushing, catching, dribbling. Object control skills—upper and lower body parts | |

| Postural stability skills | Balancing skills in general, balancing on one leg, swinging, towing, carrying an object, pushing, standing and walking on tiptoes, balancing on unstable surfaces, turning (Lindsay et al., 2022), balance (Caldwell et al., 2022), dynamic balance (Latorre-Román et al., 2021) | Modalities of postural stability: Standing on one leg Dynamic balance Postural control and posture change Postural control when interacting with objects and/or moving | |

| Physical qualities of movement | Strength and endurance, spatial awareness, proprioception, understanding movement directions, understanding time and speed (Lindsay et al., 2022) | Modalities of physical qualities of movement: Strength, motion coordination, Speed of movement, agility, Spatial awareness of space, body | |

| Cognitive | Knowledge | Mentioned, but not explained (Caldwell et al., 2022) | - |

| Understanding | Movement creativity shows no change after organized dance classes in short-term programs (Thomaidou et al., 2021) Low-height and underweight children have significantly lower developmental rates in communication and motor skills (Rico-González et al., 2024) | Modalities of understanding: Use of motion skills in an unusual way Influencing factors: Height and weight | |

| Social | Application of physical activity | Structured activities (only), unstructured activities (only), both (Lindsay et al., 2022) Movement behaviour and intense physical activity of 3-year-olds throughout the day (Ezeugwu et al., 2021) Boys do intense physical activities more than girls at age 3, but not age 2 (Trost et al., 2024) In a preschool education facility, children spend 50–60 percent of their time in physical activity (Trost et al., 2024; Lahuerta-Contell et al., 2021) Boys tend to engage in active games, girls are more likely to engage in imitation home life games, perhaps getting fewer referrals to participate in active games (Trost et al., 2024) Children communicate more frequently between peers of their gender during structured classes (Lahuerta-Contell et al., 2021) Participation in organised sports (Harlow & Fraser-Thomas, 2023) Swimming, exercise, long-term participation in sport (Harlow & Fraser-Thomas, 2023). | Modalities of physical activity: Structured organized physical activities, organised sports classes—swimming, exercise Unstructured physical activity Combinations of physical activity classes Influencing factors: Cultural impact Physical activity habits Amount of physical activity Intensity of physical activity Age Gender |

| Domains | Elements of Physical Literacy (Whitehead, 2019) | Manifestations in Behaviour | Summary: Modalities and Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective | Motivation | Fun (Harlow & Fraser-Thomas, 2023; Ltifi et al., 2024). Motivation and confidence before learning physical activity with the aim of encouraging engagement (Friskawati, 2024) | Modalities of motivation: Motivation and confidence to initiate and maintain physical activity Feeling of fun during physical activity |

| Confidence | Confidence and self-efficacy (Lugossy et al., 2022) | Modalities of confidence: self-efficacy | |

| Physical | Basic movement skills | The fine and gross motor skills depend on the children’s height (Rico-González et al., 2024) Low-height and underweight children have significantly lower developmental rates of communication and motor skills compared to normal children. (Rico-González et al., 2024) Impact of gender and cultural traditions—boys are engaged in active games, while girls are more involved in dancing or gymnastics, where postural stability is developed (Mnejja et al., 2022) Locomotor and object control skills are not developing in a coherent way (Starrett et al., 2021) Upper body object control skills can develop better under the influence of various sporting cultural traditions (Starrett et al., 2021) | Influencing factors: Internal: Height, weight, gender, External: Cultural influences The development of different categories of movement skills does not take place at the same time |

| Locomotor skills | The length of steps depends on height (Sato et al., 2022) There are improvements to targeted organised classes (Thomaidou et al., 2021) Different types of jumps and running (forward/back) (Harlow & Fraser-Thomas, 2023; Bezerra et al., 2021) Running (Caldwell et al., 2022) Climbing the stairs (Lindsay et al., 2022) Tiptoeing, jumping on the mat (Navarro-Patón et al., 2024) | Locomotor modalities: Walking in different types and styles Running Running with direction change Jumps Jumps in different ways and directions Climbing stairs Influencing factors: Internal—height, External—environment, targeted development activities | |

| Object control skills | Hand agility—precision movements, pitching accuracy, catching (Navarro-Patón et al., 2024) 6 object control skills (Bezerra et al., 2021) In the skills of strike, pitching, throwing and pushing by hands boys have performed better on hits, kicks and throws (Rico-González et al., 2024) Ball throwing (by hand), ball pushing, ball catching (by hand), ball catching and bouncing (stationary dribbling), ball pushing (stationary), ball rolling (by hand), use of outdoor play equipment (Lindsay et al., 2022) Object control—upper and lower body (Caldwell et al., 2022) Sports specific skills in various ballgame sport programs include—throws, strikes, dribbling (hand and foot), punching, rolling and touchdowns (Harlow & Fraser-Thomas, 2023) Dribble and strike (Starrett et al., 2021) Fine motor agility (Ltifi et al., 2024) | Modalities of object control skills: Upper and lower body object control skills Fine motor skills—accuracy, agility Ball skills: Upper body: throwing, pitching, pushing, rolling catching, rebounding, dribbling, touchdowns, batting Lower body: kicks, moving ball forward with legs, rolling, touchdowns Influencing factors: gender | |

| Postural stability skills | Postural balance (Stania et al., 2024; Mnejja et al., 2022) Dynamic balance (Latorre-Román et al., 2021) Posture stability, getting up and running quickly to a goal (Ltifi et al., 2024) Standing on one leg (Ltifi et al., 2024; Navarro-Patón et al., 2024) Sports specific skills: forward roll, backward roll, lying down jumps and star jumps; walking and jumping (on gymnastic beam), swinging and hanging (Harlow & Fraser-Thomas, 2023) Balance, stability and body control (Caldwell et al., 2022) Balance in general, one leg stance, swinging, towing, carrying an item while moving, pushing, standing and walking on tiptoes, balancing on rough surfaces, turning (Lindsay et al., 2022) | Modalities of postural stability Stand on one leg, dynamic balance Stability of body posture Body control skills—rolls, jumps Body control while hanging, swinging Maintaining the balance while moving, maintaining the balance while carrying, pushing objects Skills on balance surfaces—on a balance beam, unstable surfaces | |

| Physical qualities of movement | Body mass index is normal in 80% of children (Bezerra et al., 2021) Spatial awareness, proprioception, awareness and understanding of direction, time awareness and speed characteristics (Lindsay et al., 2022) Lower body strength is associated with jumping on spot, upper body strength, power, agility (Ltifi et al., 2024). | Modalities of movement qualities: Spatial perception, proprioception, awareness of direction Agility, speed and strength for lower and upper body | |

| Cognitive | Knowledge | Mentioned, but not explained (Caldwell et al., 2022) | - |

| Understanding | Linking exercise to daily routine provides cognitive bonding (Raiola, 2025) During test procedures girls listen to instructions more carefully than boys (Mnejja et al., 2022) Perceived competence influences children’s self-confidence (Barratt et al., 2024) Movement creativity (Thomaidou et al., 2021) Understanding and linking different tasks (Ltifi et al., 2024) | Modalities: Ability to maintain attention (listening) Use of mobility skills combining different skills, variability Influencing factors: gender | |

| Social | Application of physical activity | Outdoor physical activity and physical activity as a daily routine (Raiola, 2025) Boys spend more time in vigorous physical activity than girls, on average 20 min of preschool time, (Trost et al., 2024) Free play for exercise, “sense of community” (Barratt et al., 2024) Total amount of physical activity is achieved with low-intensity physical activity, with boys participating more in vigorous play (Užičanin et al., 2024) Swimming, gymnastics, soccer, football, hockey, long-term participation in sports (Harlow & Fraser-Thomas, 2023) Friendship rates changed significantly among four-year-olds in organized gymnastics classes (Yürük et al., 2024) Game-based activities promote learning with peers in a fun and interactive way (Thomaidou et al., 2021) Structured and unstructured physical activity (Lindsay et al., 2022) Daily exercise pattern—on workdays 37%, on weekends 52% of the active part of the day (Bezerra et al., 2021) Children spend 59 percent of total time active, boys are more active than girls (Lahuerta-Contell et al., 2021) Acquisition of basic movement skills often depends on the context of the environment. (Bezerra et al., 2021) An autonomy-supportive environment promotes engagement in physical activity, both child-initiated and teacher-directed, both indoors and outdoors (Barratt et al., 2024). | Modalities of physical activity: Child-initiated physical activity, teacher-led physical activity, physical activity as a daily routine, outdoor physical activity, free play, physical activity as part of the learning process, organized sports—swimming, gymnastics, football, hockey, multisport. Intensity of physical activity—factors influencing low-intensity and moderate-intensity physical activity habits: External factors: autonomous and accessible environments, internal motivation or choice, parental encouragement, neighborhood safety, outdoor temperature, proximity of roads, engagement in preschool education. Internal factors: gender, internal motivation. |

| Domains | Elements of Physical Literacy (Whitehead, 2019) | Manifestations in Behaviour | Summary: Modalities and Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective | Motivation | Fun (Harlow & Fraser-Thomas, 2023) Emotional domain under the influence of physical activity is considered to improve (Vuković et al., 2023). Motivation plays a role in the evaluation process, which is manifested by cooperation during the assessment (Vojtíková et al., 2023). The willingness to cooperate leads to the evaluation process (Vojtíková et al., 2023). | Modalities: fun, motivation as cooperation Influencing factors: improvement of the emotional domain under the influence of physical activity |

| Confidence | Mentioned, but no explanation (Caldwell et al., 2022) | - | |

| Physical | Basic movement skills | Family highly influences movement skills, sports activities and educational institution (Vojtíková et al., 2023). Fine and gross motor object control movement skills may depend on height (Rico-González et al., 2024). | Influencing factors: External: family, preschool educational institution and sports activities; Internal: Height |

| Locomotor skills | Running (Lindsay et al., 2022) Locomotor skills improve, but not significantly (Vuković et al., 2023). Single-leg jumps are better for girls than for boys, (Pelemiš et al., 2024) Results showed that body composition was not associated with lateral jump and single-leg jump test results (Pelemiš et al., 2024) | Modalities of locomotion: Running, jumping, in various ways and directions Influencing factors: Gender | |

| Object control skills | Object control—upper and lower body (Lindsay et al., 2022) Participating in organized sports school classes improves ball skills—throwing, catching, passing, dribbling (Vuković et al., 2023). Girls dominate in fine motor skills tests (Vojtíková et al., 2023) | Modalities of object control: Upper and lower body, ball handling skills—throwing, catching, passing, dribbling Influencing factors: Experience in sports school class | |

| Postural stability skills | Balance, stability and body control (Lindsay et al., 2022) Dynamic balance (Latorre-Román et al., 2021) Postural balance (Stania et al., 2024) The maturation aspect is negatively related to motor performance, mainly in terms of balance skills on a balance beam in backward movement, in which children with slightly delayed biological maturation show better results (Pelemiš et al., 2024). Girls show better results in balance skills tests (Vojtíková et al., 2023) | Modalities of postural stability: Dynamic balance, Body stability Body control during movement Influencing factors: Physical developmental maturity, gender | |

| Physical qualities of movement | Agility and strength have small correlation with cognitive ability (Vojtíková et al., 2023) Boys dominate in hand-eye coordination skills tests (Vojtíková et al., 2023) Movement coordination depends on body mass index (Pelemiš et al., 2024) Body composition affects movement coordination more in boys (Pelemiš et al., 2024) | Modalities of movement qualities: Movement coordination, agility, strength Influencing factors: Body mass index, body composition, gender | |

| Cognitive | Knowledge | Mentioned but no explanation (Caldwell et al., 2022) | - |

| Understanding | Children with reduced height and weight have significantly lower rates of development of communication and motor skills compared to typically developing children (Rico-González et al., 2024). Physical activity improves cognitive skills (Vuković et al., 2023). Object control skills by hand have a stronger correlation with cognitive ability than motor qualities (Vojtíková et al., 2023). Correlation between cognitive abilities and motor skills has been confirmed, 25–40% of motor skills affect the level of cognitive abilities and vice versa. (Vojtíková et al., 2023) | Influencing factors: External: Relationship between communication and motor skills, movement skills Improvement of cognitive skills under the influence of physical activity Object control skills with hands Internal: Weight and height, gender | |

| Social | Application of physical activity | The environment as an opportunity for physical activity (Caldwell et al., 2022) The total amount of physical activity from 3 to 6 years of age tends to decrease in about 90 percent of children, with a greater tendency for girls than boys (Caldwell et al., 2022) Participation in sports training can affect the results of specific tests—if girls in the test group play tennis, then the results of the object control skills test with a tennis ball will be affected (Vojtíková et al., 2023) Physical activity as a game (Vojtíková et al., 2023) The role of the family in the formation of physical habits (Vojtíková et al., 2023) | Modalities of physical activity: Amount of daily physical activity Organized sports training Physical activity as play Influencing factors: External: Environmental opportunities, Experience in certain types of physical activity Family’s role Internal: Age, gender |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kretaine, A.; Vecenane, H. Characteristics of the Physical Literacy of Preschool Children. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070835

Kretaine A, Vecenane H. Characteristics of the Physical Literacy of Preschool Children. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):835. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070835

Chicago/Turabian StyleKretaine, Agnese, and Helena Vecenane. 2025. "Characteristics of the Physical Literacy of Preschool Children" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070835

APA StyleKretaine, A., & Vecenane, H. (2025). Characteristics of the Physical Literacy of Preschool Children. Education Sciences, 15(7), 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070835