Abstract

Critical thinking (CT) is widely recognised as a key competency in education for sustainable development (ESD). However, international research shows that many teachers feel unprepared to teach CT, especially within the ESD context. Despite its importance, few studies have explored how CT is actually practiced in ESD, particularly in primary and secondary education. This article presents a systematic literature review of 43 qualitative studies published between 1990 and 2021, following the PRISMA guidelines. This review aimed to (1) synthesise research on teachers’ understanding of CT in ESD and (2) identify teaching practices where CT is integrated into ESD. The findings reveal that the concept of CT is frequently used but is not clearly understood in the context of ESD. Most studies focused on critical rationality (skills), with fewer addressing critical character (dispositions), critical actions, critical virtue, critical consciousness, or critical pedagogy. This review highlights a need for broader engagement with these dimensions in order to foster ethically aware and responsible citizens. We argue for teaching approaches that involve students in interdisciplinary, real-world problems requiring not only critical reasoning but also action, reflection, and ethical judgment.

1. Introduction

This systematic review aimed to identify previous studies that refer to primary and secondary teachers’ understanding of and teaching practices with critical thinking (CT), specifically in an Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) context. CT has been recognised as an important key competency in education (EU, 2016). At the same time, UNESCO emphasises the importance of ESD through Quality Education—SDG4 (UNESCO, 2017) and characterises CT as one of the core key competencies for ESD (UNESCO, 2017). It is therefore useful to investigate the nature of CT practices within ESD.

In an ESD context, CT is seen as a way to critically engage with claims from authorities (Rieckmann, 2018; Reffhaug & Lysgaard, 2024). Traditionally, CT refers to a set of (cognitive) skills and dispositions (Yuan et al., 2022); however, it has also been related to critical action, taking the social, political, and cultural aspects of ESD contexts into consideration (Bengtsson, 2022; Reffhaug & Lysgaard, 2024). This broader view of CT aligns with Leal Filho’s (2025) view on ESD that “sustainability education is not merely about the transfer of knowledge but encompasses the transformation of educational paradigms to embrace a holistic approach—one that fosters critical thinking, systems thinking, and active participation” (p. 429). International studies imply that teachers recognise this broader view (Oner & Aggul, 2023) and the importance of considering both ESD and CT, but many teachers lack an understanding of what the concepts entail (Andersson et al., 2025; Choy & Cheah, 2009) and often feel unprepared to teach CT (Aliakbari & Sadeghdaghighi, 2013; Yuan et al., 2022), particularly in the context of ESD (Timm & Barth, 2020).

In recent years, a few studies have explored teachers’ perceptions of CT at higher education levels (Choy & Cheah, 2009; Santos, 2017; Christodoulou & Papanikolaou, 2023), but how CT can be, and has been, addressed in teaching remains relatively unexplored (Thorndahl & Stentoft, 2020). Also, few studies of CT have been directed at primary and secondary education (M. Davies & Barnett, 2015; Marin & de la Pava, 2017). Even fewer studies have investigated teaching practices of CT in relation to ESD, and studies from Scandinavia describe an untapped potential to connect ESD with CT in schools and curricula (Munkebye et al., 2020; Scheie et al., 2022). Indeed, recent studies suggest that educational approaches to ESD can benefit from including a broad approach to CT that includes action (Bengtsson, 2022; Reffhaug & Lysgaard, 2024). To our knowledge, based on literature searches, no studies have systematically explored teachers’ practices of CT in ESD using a broad range of aspects of CT, from skills and dispositions to criticality perspectives, and we argue that this is needed in order to fully appreciate the potential of using CT in an ESD context. The purpose of the current review was therefore to make visible and help fill the gaps in the literature and to support teachers in their daily teaching of CT in the context of ESD. For this purpose, we analysed research on teachers’ understanding of CT in ESD, and we discuss what the literature suggests good teaching practices might look like in this context. The aim of the present study was therefore twofold—to identify and synthesise qualitative research about teachers’ understanding of CT within the context of ESD, and to identify teaching practices where CT is discussed within an ESD context.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. CT as a Key to ESD

The concept of ESD stems from the United Nations’ (UN) declaration of the “Decade of ESD” (2005–2014), although the idea of education as key to sustainable development goes back further (UN, 1992). The UN considers three intertwined components of sustainable development—economic development, social development, and environmental protection—that are seen as “interdependent and mutually reinforcing pillars” towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (UN, 2005, p. 12; Giddings et al., 2002). These three components, or pillars, have also been widely addressed in education (Sinakou et al., 2019; Öhman, 2008). In The 2030 Agenda Roadmap for Sustainable Development (UNESCO, 2020, p. 6), stepping up actions is one of the priority areas. Indeed, it is considered essential that students—as future citizens in the sustainable world—are able to act within a sustainable development context. However, few concrete recommendations to increase students’ actions exist, which makes it difficult for teachers to empower students towards action (Wilhelm et al., 2019). To this end, CT is presented as a means to enable individuals and groups “to contribute to sustainability in genuinely autonomous and authentic ways” (Tilbury, 2011, p. 30). This also means that CT offers the possibility to question potential ESD practices (Jensen & Schnack, 2006; Bengtsson, 2022). Moreover, in the ESD context, tasks are often action-oriented, recognising that critical cognition and critical doing are important aspects to deal with. Therefore, the recognition of critical doing in ESD has a socio-cultural aspect that is important to consider in education (Bengtsson, 2022).

Furthermore, ESD is interdisciplinary in its nature, and despite it often being associated with natural sciences and the natural environment, it is frequently covered in different school subjects in different countries (Hallingfors & Åström Elmersjö, 2025). The interdisciplinarity of issues related to sustainability makes them suitable for training students to critically engage with the different perspectives on the matter. Due to this interdisciplinary nature of sustainability issues, our systematic review also characterises which school subjects are considered in the included studies. When students work on such complex sustainability issues, it is recommended that they are given the opportunity to “ask critical questions, collaborate, conduct investigations, evaluate, and discuss findings in a broader context” (Bjønnes, 2017, p. 22). Indeed, as argued above, CT has been highlighted as a key competence for addressing sustainability challenges (Rieckmann et al., 2017).

2.2. Defining and Identifying a Framework for CT

The concept of CT has been defined as “reasonable reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do” (R. H. Ennis, 2015, p. 32) and is described as critical for decision-making (EU, 2016; Ministry of Education and Research, 2017) and as a crucial competence for ESD (Rieckmann et al., 2017; Taimur & Sattar, 2020). However, although CT has a long tradition in academia, there is a reported lack of precision as to what the concept entails (Thomas & Lok, 2015; Gunawardena & Wilson, 2021; M. J. Davies & Willing, 2023; Andersson et al., 2025). Similarly, few directions for how to teach CT in schools exist (Noddings, 1995; Thomas & Lok, 2015). CT can be taught as a generic cross-curricular skill (R. H. Ennis, 1987) or within domain-specific contexts, each with their specific characteristics (Abrami et al., 2015). According to Andrews (2015), it is the nature of disciplines that creates the specificity within which argumentation of a particular kind is undertaken, where the teaching gradually goes from generic to domain-specific CT as individuals become more specialised in their area of interest. Either way, it has been argued that teaching CT is most efficient when the principles of CT are made explicit (R. Ennis, 2013). In light of this, it has been recommended that approaches and strategies to teaching CT should be developed in disciplinary or thematic contexts (Yuan et al., 2022). ESD can be a thematic (and interdisciplinary) context for CT instruction that simultaneously strengthens ESD, as argued above.

Three approaches to CT can be identified in the literature (E. R. Lai, 2011; E. Lai et al., 2017; Thomas & Lok, 2015) based in philosophical, psychological, and educational traditions, respectively. In the field of education, within which we position this study, Facione (1990) has defined CT as purposeful, self-regulatory judgement that results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference. In addition, explanations of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual factors upon which a certain judgement is based are considered part of CT in this tradition.

As noted above, CT has traditionally been described as two interconnected sets of attributes—namely, composites of skills and dispositions (Facione, 1990; R. H. Ennis, 2015; E. R. Lai, 2011; E. Lai et al., 2017; Thomas & Lok, 2015). Thomas and Lok (2015) have categorised CT skills into three subgroups: reasoning, evaluation, and capacity for reflection and self-regulation, where reasoning comprises the ability to identify and explore evidence through acts of reading, discussion, inference, and explanation. Evaluation, the second skill set, involves interpretation and analysis. The third skill set involves the capacity for reflection and self-regulation. Dispositions can be divided into those that are related to the self, to others, and to the world, as well as ‘other’ (mindfulness and critical spiritedness) (M. Davies & Barnett, 2015). Skills and dispositions make up what has been referred to as the critical thinking movement, in which CT is perceived as individual qualities consisting of the cognitive elements (described as skills above) and the propensity or character attributes of the person (also referred to as dispositions or abilities) (M. Davies, 2015).

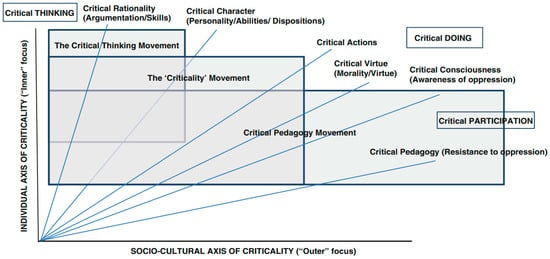

M. Davies (2015) has advocated for a broadening of the view of CT beyond skills and dispositions because in this vision, CT as potential actions is missing. This view is in keeping with UNESCO’s calls for action in autonomous and authentic ways, as discussed above. While the CT movement is more preoccupied with individual qualities, two additionally named “movements”—the criticality movement and the critical pedagogy movement—are embedded in the socio-cultural aspect of CT and the collective (Figure 1) (M. Davies, 2015). The criticality movement signifies attempts to incorporate critical action. Indeed, Burbules and Berk (1999, p. 52) state that criticality requires that “one be moved to do something”. This means that criticality sees the individual as a starting point and emphasises the importance of engaging actively with the world.

Figure 1.

M. Davies’ (2015, p. 77) visualisation of the three movements—The Critical Thinking Movement, The ‘Criticality’ Movement, and The Critical Pedagogy Movement, which all describe aspects of CT. Reproduced with the kind permission of Martin Davies.

The critical pedagogy movement, however, begins from a different starting point compared to the other two mentioned movements because it emphasises educating for radical pedagogy (M. Davies, 2015). It considers CT as the critique of lived social and political realities to ensure freedom of thought and actions (Kaplan, 1991) and therefore draws attention to the ways in which knowledge, power, and experience are produced under certain conditions of learning. This means that critical pedagogues are focused on the presence of ideology in social institutions’ discourses (M. Davies & Barnett, 2015). Therefore, critical pedagogy contains a social dimension within the concept of CT that potentializes the importance of applying critical thought to enact social change in ESD contexts (Reffhaug & Lysgaard, 2024). In our view, this makes an important addition to the conceptualisation of CT if one wants to use CT to advance ESD.

M. Davies (2015) therefore considers CT in a broad sense. On the left side of Figure 1 lies critical rationality (argumentation/skills) and critical character (personality/abilities/dispositions), followed by critical actions, critical virtue (morality/virtue), critical consciousness (awareness of oppression), and finally critical pedagogy (resistance to oppression). The axes focus on CT as a movement (shaded box) from the CT movement near the Y axis, via the criticality movement and to the critical pedagogy movement, which extends to the right on the X axis, showing the degree to which individual or socio-cultural aspects of criticality in each of the movements are most pertinent. The diagram also shows how ‘critical thinking’, ‘critical doing’, and ‘critical participation’ are positioned on the criticality and socio-cultural scales. In the field of education, CT has been identified as a dialogical practice (Kuhn, 2019). Consequently, an ever-changing environment requires the teachers’ ongoing interpretations. In teachers’ interpretations, thinking in action and on action (Schön, 1983) constitute an essential aspect of their professional practice. Thinking in action and on action can be devised as the thinking in action occurring when events happen, while thinking on action is characterised as thinking after a particular event. We therefore see Davies’ framework as particularly suited for a discussion on how to teach CT in an ESD context.

Using M. Davies’ (2015) framework, therefore, this systematic review offers a way to understand how CT in different conceptualisations (critical rationality, critical character, critical actions, critical virtue, critical consciousness, and critical pedagogies) can contribute to understanding how CT has been used in ESD. M. Davies’ framework (2015) has recently been cited in studies on CT in an ESD context (Reffhaug & Lysgaard, 2024; Christodoulou & Papanikolaou, 2023), which further supports its relevance for our study. However, we argue that its potential as an analytical framework has hitherto not been fully exploited. This study attempts to fill this gap by analysing how a broad understanding of CT has been used to teach ESD. To this end, the research questions that guided our literature review are as follows:

With respect to critical rationality, critical character, critical actions, critical virtue, critical consciousness, and critical pedagogies, what does the literature reveal about (1) how teachers understand CT (in ESD) and (2) how they (can potentially) practice this in their teaching?

3. Materials and Methods

The current study was conducted as a systematic review (Booth et al., 2012, 2019). According to Booth et al. (2012), a systematic review seeks to aggregate and integrate views from multiple studies, avoiding exaggerated emphasis on one or a few studies. To this end, the present study adopted a qualitative evidence synthesis that aimed for variation in concepts rather than an exhaustive sample. This means that to allow for the broadest possible variation within the included studies, we used maximum variation purposive sampling to select from the eligible studies (cf. Booth et al., 2019).

In addition to the analysis addressing the research questions, we mapped the scope of the included articles with respect to country, school level and subject, and the number of articles per year. On top of providing context for the systematic review, the resulting information helped to identify potential skewness in the research as well as gaps in research regarding certain school levels, subjects, or regions of the world. A scoping analysis is quantitative in its nature; however, to address our main research questions, we focused on non-numerical data because our interest was not to establish quantitative relationships but rather to capture a breadth of understandings and practices as they have been communicated and studied in the literature in a given period. To capture a plethora of approaches to CT in ESD, we also included literature that has proposed teaching practices without trying them out systematically.

3.1. Data Collection

To allow for a broad variation of studies, we included as many articles as possible to inform our review. The following databases were searched: Education Source (EBSCO host), ERIC (ProQuest), Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Epistemonikos, Google Scholar, OpenGrey (EU), and Idunn (Scandinavian University Press’s platform for academic journals and books). The database search was combined with a reference-checking procedure whereby articles from the reference list were downloaded and added to the existing Endnote library.

To ensure that only qualitative studies were included, a methodological filter was applied for the databases for which this function was enabled. When possible, we also included a filter to select primary, elementary, middle high school, and junior high school levels. The search strategy procedures for all databases are presented in Table 1. We also searched for so-called ‘grey’ (‘gray’, ‘fugitive’) literature (Booth, 2016, p. 10) through OpenGrey (EU) and Google Scholar to include as many types of publications as possible. For Google Scholar, we browsed and selected from the first 200 records only, as per the recommendation in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins & Thomas, 2019). The searches were conducted between January 2022 and January 2023.

Table 1.

Search strategy procedure for each database.

3.2. Article Selection Criteria

Two of the authors conducted a pilot search of the Education Source database before expanding the search to the remaining databases. Because this search only generated a limited number of records (n = 45) (Appendix A), of which many were assessed to be of uncertain relevance, it was decided to search for literature on CT without considering it together with ‘education for sustainable development’ (Appendix B). The rationale for this search strategy was to ensure a sufficient number of records and to then add ESD concepts as manual search criteria in the next step of the selection process. The overall selection criteria that were used to select the articles are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selection criteria: Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

A protocol entitled “Teachers’ Own Accounts of Conceptualization and Teaching About Critical Thinking and Education for Sustainable Development: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis” was submitted on 18 February 2022 to PROSPERO, the international prospective register for systematic reviews, with the ID: CRD42022304197 (EPOC, 2020).

3.3. Screening and Review Procedure

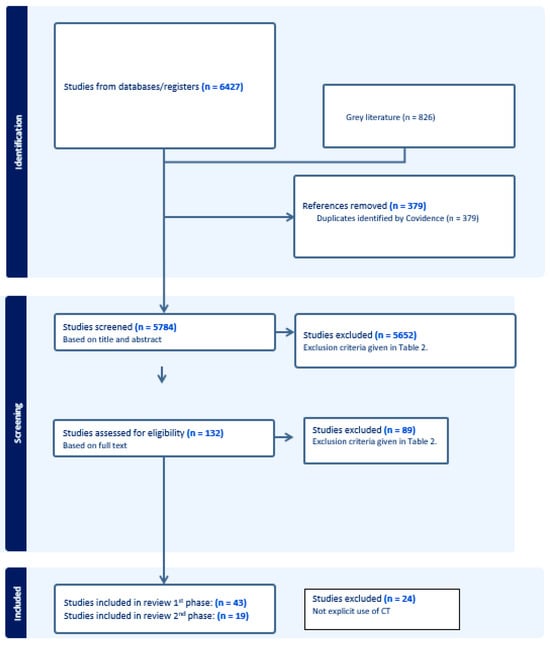

The retrieval of the reviewed studies followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses) standards for systematic literature review (PRISMA, n.d.) and was based on a multiple-step procedure, which is presented below. The results of the literature search and study selection are summarised in the flowchart in Figure 2. After having removed duplicates from an original sample of 6427 articles, 5784 were screened for inclusion in the review. In the first phase, the study selection process resulted in 43 included studies (Appendix C). Later, after reading all 43 articles, we focused on 19 articles in a second phase in which we considered the explicit use of CT.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flowchart diagram of the screening and selection procedure. Based on PRISMA (n.d.) 2020 guidelines and retrieved from Covidence.

All publications were retrieved to Covidence, which is a web-based platform (Covidence, n.d.) that is recommended by the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins & Thomas, 2019) and streamlines the process of conducting a systematic review.

3.3.1. Level One Screening Based on Title and Abstract

After removing duplicates, the retrieved list of 5784 publications was first subjected to a crude exclusion of irrelevant publications based on title and abstract information. The first level of screening was conducted by two authors. In cases of doubt, the articles were included for further review in the next screening step. Full-text versions of all selected articles were obtained.

3.3.2. Level Two Screening Based on Full Texts

All 132 articles that passed the abstract-screening phase were assessed as full texts independently and individually by the two other authors, of which 75 studies were initially excluded, and the exclusion criteria were documented (see Figure 2). At the end of the screening process, any disagreements were explored and resolved via discussion within the review team (cf. Higgins & Thomas, 2019), which led to the exclusion of another 14 articles.

3.3.3. Data Extraction

In the first phase, we included 43 articles, and relevant overall information was extracted individually by all four authors using two coding sheets based on templates from Covidence. In the first coding sheet (Data Extraction), for each title, we logged: (1) education level, (2) school subject, and (3) country of investigation. In the second coding sheet (Quality Assessment), we assessed each article with regard to: (1) CT (implicit or explicit), (2) ESD dimensions (environment, environment/economy, environment/social, and environment/economy/social), (3) the extent to which the teaching practice was explicitly (through interviews or explicit reflections) or implicitly reported, and (4) type of publication (peer-reviewed journal article, conference proceedings article, book chapter, and contribution in a teachers’ magazine).

The quality assessment point ‘3’ led to a grouping of articles into (a) intervention studies, n = 11 (where teaching practices were explicitly reported on, and where reflections on try-outs and in interviews were included), (b) modules that had not necessarily been tried out or assessed, n = 23, and (c) other articles, n = 9. The reasons for including articles on modules among our selected studies were three-fold. First, very few of the 43 articles that we reviewed involved the systematic study of teaching practices. Second, examples of teaching modules, if only implicitly, provided insight into how some teachers worked with, and found it feasible to practice, the topics of CT and ESD in their classrooms. Third, our pool might serve as a sampling of teaching modules taking up CT in an ESD context to be used by teachers and teacher educators in different fields. As a consequence, our assessment was that such literature could give a broader picture of teaching practices than just including studies of interventions. The other category consists of articles in three subcategories: (a) guidelines for science education, environmental literacy, and sustainability teaching, (b) commentaries about the needs for future education, and (c) teacher interviews about consumer education, aims for ESD, and the use of folklore. Examples include guidelines on “how to help primary and secondary students to ask questions, think critically, and make decisions, while empowering them to create and implement solutions to local sustainability issues” (McKeown, 2013, p. 15) and a commentary about “the advantage of incorporating high level thinking skills and interdisciplinary science and social studies in classrooms” (Kumar & Fritzer, 1994, p. 4). In the second phase, we included 19 articles that considered the explicit use of CT (as explained and further developed below in the next section).

3.4. Data Analysis and Analytical Framework

As a step in the data extraction process described above, we distinguished between articles in which CT was mentioned implicitly and explicitly, and we identified which of the three pillars of ESD were addressed in the entire pool of included articles. All articles for which CT had been explicitly mentioned (n = 19) were analysed using M. Davies’ (2015) framework for CT (Figure 1) in order to identify which aspects of CT were covered in the different contributions. The coding scheme with sample statements from the articles is included in Table 3. This table was developed over several rounds of dialogue between all of the authors.

Table 3.

Coding scheme inspired from M. Davies (2015).

In the second phase of the analysis, we examined the relationships between the dimensions of ESD and the different aspects of CT. Furthermore, we took a closer look at the intervention studies and module-based articles specifically in order to identify which ESD pillars had been addressed in the interventions and modules that were presented and to look for trends across CT aspects and ESD dimensions.

Similarly, the sorting of articles into categories went through several steps. An initial sample categorisation and development of the coding scheme was performed among the team, and responsibility for different categories was then assigned between the four authors. In the final round, the categorisation was first reviewed by one author, who suggested revisions, then reviewed and re-checked by two other authors, whereupon new revisions were made, which were discussed within the team until consensus was reached. Similarly, the grouping into intervention studies, module-based articles, and ‘other’ was also subjected to several revisions between the authors during the review process.

It should be noted that, in agreement with M. Davies (2015), we believe that CT can be evaluated along all of the outlined dimensions simultaneously; therefore, the separation into separate categories does not imply that these exist independently of the others.

4. Results

As explained above, the present systematic review started out with a sample of 43 articles, whereupon a focused sample of 19 articles for which CT had been found to be described explicitly was analysed. To provide a context for our discussion, in this Results section, we will start with an overview of the general characteristics of all 43 studies and the extent to which the different ESD pillars were addressed. Thereafter, we present the results of the analysis of the sub-sample of 19 articles, with a specific focus on CT aspects (M. Davies, 2015) and ESD pillars. All 43 articles, sorted by article type, are listed in Appendix C, and the 19 selected articles are marked in bold.

The ‘explicit’ category that led to the focused subsample of 19 articles was only used if the authors defined or indicated what CT entailed in their study or module. In the articles sorted within the ‘implicit’ category, CT was mentioned but not explained. Interestingly, only 8 of the 23 module-based articles explicitly addressed CT (Brown & Golden, 2017; Deaton & Cook, 2012; Garzón et al., 2019; Goodwin, 2014; Heller, 1997; Karvankova et al., 2020; Rahman et al., 2019; Sperry, 2020), while this was the case for 6 of the 11 intervention articles (Ampuero et al., 2015; Barakiti & Bokolas, 2014; Jackson et al., 1997; Muthersbaugh et al., 2014; Pedretti, 1999; Proulx, 2004) and for 5 of the 9 studies in the ‘other’ category (Blatt, 2015; Hasslöf & Malmberg, 2015; Hicks, 1991; Kumar & Fritzer, 1994; McKeown, 2013). As noted, these 19 articles (see Table 4) were selected for the second phase of the analysis, with a focus on CT aspects and ESD dimensions.

Table 4.

Results of the systematic review of the 19 articles that explicitly mentioned CT. Codes: I—Intervention study, M—Module-based article, O—Other; PR—Peer-reviewed journal articles; J—Journal article, TM—Article in teachers’ magazine, CP—Conference proceedings article, BC—Book chapter, CR—Critical rationality, CC—Critical character, CA—Critical action, CV—Critical virtue, CCo—Critical consciousness, CP—Critical pedagogy, * No information about peer review process available. Also note that reviewing practices may have changed over time.

4.1. General Characteristics of All Included Studies (n = 43)

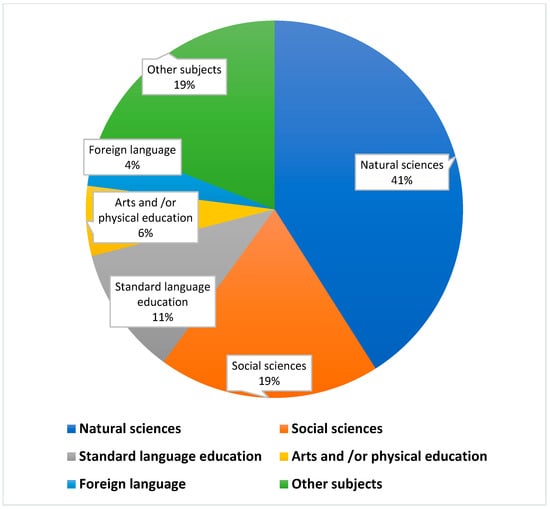

We present here the scope of the extended sample of 43 articles with respect to geographical distribution, school level, school subject, and number of publications per year interval. In terms of geographical spread, 64% of the 43 studies took place in the Americas (58% in North America) and 20% in Europe. A small proportion of the articles originated in Australia (7%), Asia (7%), and South Africa (2%). Almost half of the studies (41%) were conducted at the primary school level, followed by studies from middle school (32%) and secondary school (which includes junior high school, at 23%). Some overlap between middle school and primary or secondary school might be assumed because different terms are used for the same age groups in different countries. Together, middle and secondary schools made up the majority of the studies (55%). Finally, very few studies (4%) dealt with ‘all school levels’. With regard to the disciplinary context of the studies, unsurprisingly, the majority (41%) of the included articles (n = 24) dealt with CT while teaching ESD in a natural science context (see Figure 3), and 56% of the articles targeted more than one subject. A few studies were conducted within an interdisciplinary teaching context, such as environmental or sustainability education. A total of 65% of the included articles were published in or after 2015, while 35% were published from 1991 to 2014.

Figure 3.

Distribution of school subjects for which the included studies or modules were investigated or designed (n = 43). Note that most articles (56%) discussed more than one school subject. The ‘other subjects’ category included subjects such as mathematics, and also interdisciplinary fields such as sustainability education.

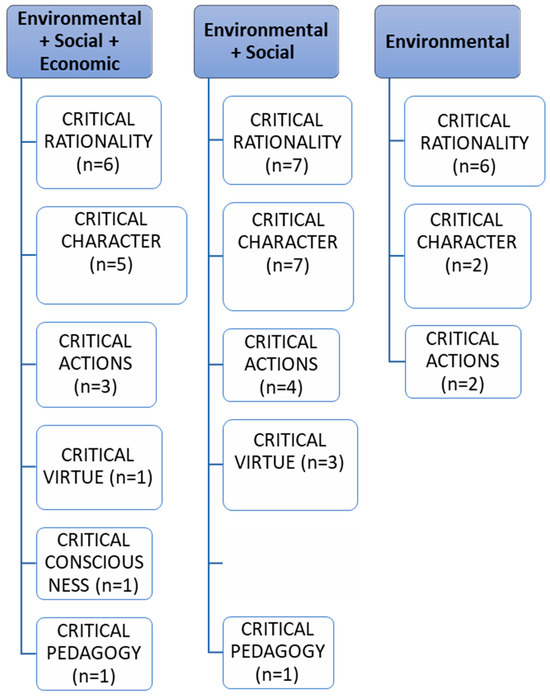

As for the three pillars of ESD (Table 4, right column), 12 articles (26.5%) were found to include environmental, societal, and economic aspects, 12 articles (26.5%) included only environmental and societal aspects, and 19 articles (47%) exclusively dealt with environmental issues. We found no articles that only dealt with environmental and economic dimensions. Only six of the articles that explicitly addressed CT covered all three pillars of ESD (29%); three were module-based articles (Deaton & Cook, 2012; Goodwin, 2014; Sperry, 2020), two were intervention studies (Kumar & Fritzer, 1994; McKeown, 2013), and one was from the ‘other’ category (Proulx, 2004).

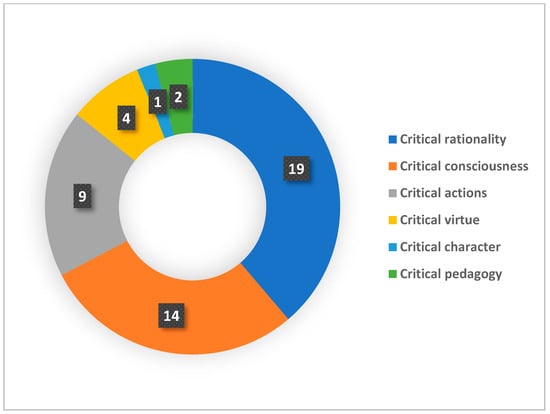

4.2. CT Aspects Addressed Explicitly (n = 19)

When analysing the articles that explicitly referred to CT (Table 4) with regard to M. Davies’ (2015) categories (Figure 1), we found that all 19 articles referred to critical rationality, and more than half referred to critical character (n = 14) (Figure 4). Many articles also included aspects of critical actions (n = 9), which here is broadly defined to also encompass explicit plans for actions. We also uncovered elements in the studies that referred to critical virtue (n = 4), critical consciousness (n = 1), and critical pedagogy (n = 2).

Figure 4.

Distribution of CT explicit categories. n = number of articles.

In terms of critical rationality (n = 19), we identified a variety of skills from all three sets of skills suggested by Thomas and Lok (2015), including explanation (reasoning), evaluation, interpretation and analysis (evaluation), and reflection and self-regulation (capacity for reflection and self-regulation). Of all the included articles, more than half (n = 14) referred to critical character, especially those classed as being in relation to self and in relation to others (M. Davies & Barnett, 2015). For example, dispositions to asking questions (e.g., Muthersbaugh et al., 2014; Kumar & Fritzer, 1994; Hasslöf & Malmberg, 2015), promoting empathy (Karvankova et al., 2020; Ampuero et al., 2015), and open-mindedness and respect for alternative viewpoints (e.g., Ampuero et al., 2015; Blatt, 2015; Garzón et al., 2019; Karvankova et al., 2020; Proulx, 2004) were discussed.

Some of the included articles referred to teaching practices that can be considered as critical actions (n = 9). We identified environmental actions such as building and engaging in a school garden, (Ampuero et al., 2015), proposing possible solutions to reduce the use of plastics in students’ daily life (Garzón et al., 2019), or suggestions for measures at home to preserve the environment (Heller, 1997). We also found environmental actions that involve perspective-taking and actions directed at a better future (Blatt, 2015; McKeown, 2013; Muthersbaugh et al., 2014), such as lessons using visual images to encourage students to solve present and future environmental problems (Muthersbaugh et al., 2014). Environmental actions were also related to social responsibilities, such as a town hall debate, and activities that promoted students’ participation in public life, such as proposing solutions to global issues at a local scale (Goodwin, 2014; Karvankova et al., 2020). For example, Karvankova et al. (2020, p. 150) wrote: “The intention of the discussion is to incite the development of public responsibility for their surroundings, and to encourage a modification of pupil behavior towards the values of sustainable and ecological development as a way of life.”

References to critical virtue (n = 4) included virtues of social reconstruction and social good (Pedretti, 1999), taking ethical stands towards resolving peace, conflict, and human rights issues (Hicks, 1991), and teaching values such as solidarity and cooperation among all peoples (McKeown, 2013). In the critical consciousness category (n = 1), McKeown (2013) connects pieces of clothing to resources, manufacturing, and labour around the world, indicating that cheap labour is one root basis for cheap prices in the West.

Finally, two studies were found to include critical pedagogy, which is a dialogical engagement with actions that participants take in relation to solving issues or problems. Hicks (1991) described global education as a process of exploring relationships between the personal and the political dimensions, including investigating how organisations work to create critical social change. According to McKeown (2013, p. 13), pedagogies associated with ESD “do more than point out what is wrong in the world; they empower students to find and implement solutions”.

4.3. ESD Aspects in Intervention Studies and Module-Based Articles That Explicitly Address CT

When sorting the 19 studies into the identified ESD dimensions and CT categories, interesting connections appeared (Figure 5), and a prerequisite for the categories of critical virtue, critical consciousness, and critical pedagogy to occur is that the social dimension of ESD needs to be present. All but two of the articles that addressed critical action also included the social pillar of ESD. In the following, we will elaborate in more detail on how the intervention studies and the module-based articles incorporated the different dimensions of ESD.

Figure 5.

Connections between ESD dimensions and CT aspects (n = 19).

Six of the intervention studies and eight of the module-based articles treated CT explicitly. The contexts of the interventions and modules included geographical fieldwork, building a life lab (garden), building wiki-based tools through problem-based learning, investigating the use of plastics through mathematical analyses of data, reading and writing about environmental issues, using images in place-based lessons, role-play about algae in a lake, assessment of information about climate change and photosynthesis, and classroom debates. With regard to CT aspects from M. Davies’ (2015) framework, the intervention studies and module-based articles covered critical rationality (all), critical character (n = 10), critical actions (n = 6), and critical virtue (n = 1). No articles covering critical consciousness or critical pedagogy were found (Table 4).

In an intervention study that addressed environmental, social, and economic issues, Proulx (2004) suggested that classroom debates are an opportunity to help students establish links between elements of the scientific method that they learned over the years and to develop CT through firsthand involvement by asking questions, assessing claims (critical rationality), and acquiring respect for alternative viewpoints (critical character). In a module-based article that covered all three pillars of ESD, Goodwin (2014) addressed critical rationality, critical character, and critical actions in a teaching module that invited students to consider the practices of hydraulic fracturing or fracking, including social and environmental aspects of land, water, waste, and air considerations. Goodwin (2014) argued, “The intense debate over fracking can be framed as an epitome of the struggle or tension between contrasting worldviews: environment/economy, short-/long-term, biodiversity/monoculture”. One intervention study—Pedretti (1999)—also addressed the aspect of critical virtue by examining the environmental and social pillars of ESD through role-play about a socio-scientific issue centred on mining. Here, students were invited to discuss principles of justice and what is ‘good’, ‘bad’, or ‘right’.

Ampuero et al.’s (2015) intervention study, which concentrated on the environmental and social pillars of ESD, focused on empowering decision-making capacities in order to develop students’ thinking and empathy skills within the context of ESD (here given as a life lab). This intervention indicated that critical thinking skills such as self-regulation, interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, and explanation (critical rationality), in combination with empathy (critical character), could help to improve the disposition towards sustainable behaviours in young citizens at a primary school level. When developing the affective domain, the authors argued, the students are comforted and willing to learn how to guide the thinking process. This involves an in-depth level of understanding of what is happening, and the students might be able to problem-solve with more clarity and security, leading to actions (critical actions): “For the children, love was the most interesting and valuable topic. They highlighted this by applying the concept of environmental love to the thinking process and how it drove them to endure and continue to grow as thinkers and keep fighting to solve various problems in their lives” (Ampuero et al., 2015, p. 74). Ampuero et al.’s (2015) study exemplifies how a teaching approach combining cognitive and affective domains with an explicit focus on CT skills and empathy skills can help students to make decisions and prepare them to positively meet imposing present and future challenges.

5. Discussion

The research questions guiding this systematic review were, with respect to critical rationality, critical character, critical actions, critical virtue, critical consciousness, and critical pedagogies, what does the literature reveal about (1) how teachers understand CT (in ESD) and (2) how can they (potentially) practice this in their teaching?

Teachers’ understanding of CT was presented in very few articles in this systematic review. Therefore, this first research question must, to a large extent, be answered indirectly through an analysis of which aspects of CT have been addressed in interventions or published modules. The second research question, about the potential use of CT in ESD, will partly be answered through teachers’ reported practices as part of intervention studies, or through the modules that have been proposed and partly tried out in classrooms at primary or secondary school levels. While we will start by addressing each question separately, we acknowledge that the two questions are intertwined. Thus, we will conclude the discussion by looking at both questions together, as seen through a breadth of literature, including teacher interviews, proposed teaching modules, and qualitative intervention studies as well as commentaries and guidelines.

5.1. How Do Teachers Understand CT (in ESD)?

The fact that fewer than half of the 43 originally included articles explicitly addressed CT suggests that CT is frequently used as a buzzword without filling it with precise meaning. This is in line with what others have found (Thomas & Lok, 2015; Gunawardena & Wilson, 2021; M. J. Davies & Willing, 2023; Thorndahl & Stentoft, 2020; Andersson et al., 2025). Indeed, teachers often find it hard to work with CT in their classroom because it is not clear to them what the concept entails and therefore it is not clear how they can develop this competence with their students. Miri et al. (2007) found in their study that teachers who teach with awareness, with appropriate purposes, and with an explicit focus on promoting students’ CT increase the likelihood of success. R. Ennis (2013) also argued that the CT principles need to be explicitly taught because leaving the principles as implicit will not support a transfer of CT to other subjects or to students’ everyday life. In the following, we will therefore discuss the selected 19 studies in which CT was mentioned explicitly (Table 4).

To capture the CT aspects that were addressed in these selected articles, going beyond the traditional sets of skills and dispositions, the results revealed that, unsurprisingly, all 19 articles included critical rationality (skills) as part of CT, while 14 also addressed critical character (dispositions). The critical thinking movement is therefore broadly embraced in the ESD teaching contexts that we studied. This corresponds well with the findings of Abrami et al. (2015), who argue that CT skills and dispositions can be developed at all levels of education across all disciplinary areas. This finding is also in line with other studies, such as that by Munkebye and Gericke (2022), who state that primary teachers in the Norwegian school context mostly emphasise skills and not affective elements such as imagination, empathy, emotion, and intuition. Instead, teachers emphasise the skills of source criticism; examining, detecting, and analysing arguments; engaging in logical reflection, drawing conclusions, and justifying arguments. In our review, one intervention study, which was conducted in Chile (Ampuero et al., 2015), explicitly aimed to develop empathy and CT, which implicitly implies that empathy was considered part of CT. Their findings revealed a significant benefit in using empathy strategies to engage students regarding the thinking processes that are involved in solving environmental problems. Cultural differences in approaches to CT (Howe, 2004) might also explain the emphasis on the CT movement in our sample, which was dominated by countries in North America and Europe.

More interesting, however, is whether, and if so, to what extent, the two ‘additional’ movements—the ‘criticality’ movement and the critical pedagogy movement—that contribute to a broader view on CT are considered part of CT as it is understood in an ESD context (cf. Bengtsson, 2022; Reffhaug & Lysgaard, 2024). To analyse this, we considered the CT aspects that are addressed, along with the ESD pillars covered in each article (Figure 5). As noted above, the categories of critical virtue, critical consciousness, and critical pedagogy seem to require that the social dimension of ESD is present. This is in keeping with M. Davies’ (2015) diagram (Figure 1). This review demonstrates that CT is seen as closely linked to social engagement and citizenship and thus goes beyond skills and dispositions.

5.2. How Can Teachers Practice CT in ESD?

In Ampuero et al.’s (2015) study, the students were engaged in the critical action of building a life lab (‘the garden’). Through building and maintenance of the garden and through outings to the park, forest, vegetable market, the adjacent plaza, and nursing homes, the students showed a shift in consciousness, in that they became more aware of personal welfare and the environment. The interdisciplinary nature of the course and its theoretical and practical components provided opportunities to coordinate thematic areas and to explore the connections between natural and social systems.

Dialogue, group discussions, and debates are considered to be effective approaches for CT teaching by several authors in our sample (Brown & Golden, 2017; Deaton & Cook, 2012; Goodwin, 2014; Pedretti, 1999). Indeed, Abrami et al. (2015) found that opportunities for dialogue (e.g., discussions), the exposure of students to authentic or situated problems and examples, and mentoring are effective strategies for teaching both generic and topic-specific CT skills and CT dispositions at all educational levels and across all disciplinary areas. Authentic problems taking ESD as a context were also mentioned in some of the articles in our sample (Deaton & Cook, 2012; Garzón et al., 2019; Jackson et al., 1997; Karvankova et al., 2020; Pedretti, 1999).

In Karvankova et al.’s (2020) article, cross-curricular links between geography, biology, physics, civic education, ecological education, and personal and social education are encouraged. Natural science was included in most studies and modules in our selection (41%, see Figure 3). Although 19 of the 43 articles dealt with one single subject, more than half of them (n = 24) dealt with two or more subjects. Moreover, several studies emphasise interdisciplinarity as a prerequisite for successfully solving sustainability problems—e.g., as stated by McKeown (2013, p. 15): “Many real world problems are so complex that they require multi-perspective or multidisciplinary teams to analyze the problems as well as to propose, evaluate, and implement solutions.” ESD can be such a complex and interdisciplinary topic, for which CT is considered a crucial competence (Rieckmann et al., 2017; Taimur & Sattar, 2020; Hallingfors & Åström Elmersjö, 2025).

By including module-based articles along with intervention studies, interview studies, guidelines, and commentaries, we have been able to map a large extent of teaching contexts for CT in ESD that would not otherwise have been possible to detect. We will conclude with some final remarks on CT in ESD, as seen from theoretical and practical perspectives, before we finally address the qualities and limitations of this study.

5.3. CT in ESD in Theory and Practice

According to Facione (2016, p. 6), a person can be strong at CT but still not be an ethical critical thinker. This is in line with M. Davies’ (2015) idea that the possession of skills and dispositions alone do not suffice for a person to become a critical citizen. Critical actions and ethical behaviour might be seen as related. In our selection of studies, there are some examples of how critical actions can be implemented in classrooms. This knowledge is a prerequisite for developing teachers’ CT practices. Indeed, as Blatt (2015) demonstrated in their interview study, teachers’ understandings and ideals do not always align with their actual practice; for example, the teacher Mrs. P explicitly stated that she was “purposefully” not “trying to work on their behavior” (Blatt, 2015, p. 722), while this was exactly what the students felt that she was doing.

According to Siegel (1988, pp. 55–61), “Education should prepare children to become democratic citizens, which requires reasoned procedures and critical talents and attitudes.” Recently, it has been suggested that the real educational goal is recognition, adoption, and implementation by students of those criteria and standards used in the CT process (Hitchcock, 2020). This includes attaining the knowledge, abilities, and dispositions of a critical thinker and extending this to their everyday lives as informed citizens (Facione, 2000; Hitchcock, 2020). In these everyday lives, teachers are practising a reflective form of knowing in action when events happen (Schön, 1983) and when using knowledge, abilities, and dispositions.

5.4. Quality of This Study and Its Limitations, Implications for Practice, and Future Directions

Regarding the scope of the studies presented in this systematic review, although we were openly looking at different languages, 58% of the 43 studies were from North America. This fact might point to a limitation in this research because we were still not able to incorporate more studies from Asia or Africa, and it remains unclear if this is because of the choice of the databases we used. Another limitation of this systematic review is that a significant number of the studies (n = 23) were module-based. This indicates that they have not been systematically implemented in a classroom setting. In terms of the reliability of this systematic review, we submitted a protocol following the Qualitative Evidence Synthesis protocol and review template (cf. EPOC, 2020). In addition, we followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (PRISMA, n.d.) while applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria (as indicated in Section 3.2) and following the established data extraction procedures (Section 3.3.3) to ensure the validity and transparency of this study (cf. Tong et al., 2012).

In the context of ESD, and based on this review, we indeed suggest that teachers’ use of CT should include more than just critical rationality and critical character. But more research is needed, for example, to see whether it is easier to inspire and prepare students for critical actions if the teacher practices critical virtue. Based on this literature review, we also conclude that more research is needed to clarify teachers’ understanding of CT more explicitly. In our view, when teachers use critical pedagogy as part of the critical pedagogy movement (M. Davies, 2015), they have the opportunity to think on action, a reflective practice that occurs after an event (Schön, 1983) in the context of ESD. We propose a need for engaging students in interdisciplinary problems that face critical actions, critical virtue, critical consciousness, and critical pedagogy for them to be responsible citizens with ethically conscious behaviour. We recognise that CT in education is a dialogical practice (Kuhn, 2019). Therefore, such education benefits from a broader spectrum of CT in ESD, rather than a focus on skills and dispositions—and this forms the critical thinking movement (M. Davies, 2015).

The fact that less than half of the studies (41%) were conducted at the primary school level can be a promising area for future research in investigating teachers’ use of CT in ESD with a specific focus on interdisciplinarity. Finally, we recommend using M. Davies’s (2015) framework including critical rationality, critical character, critical actions, critical virtue, critical consciousness, and critical pedagogies to investigate the practice in teacher education and therefore revitalise CT approaches in ESD in teachers’ practice.

We have assumed in this study the centrality of the broad use of CT in ESD, and this stance brings out the perception that specific studies are still needed on the economic pillar (whether associated or not with the environmental and social pillar) of ESD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.F.; Formal analysis, S.M.F., M.L., A.L. and R.L.S.; Investigation, S.M.F., M.L., A.L. and R.L.S.; Methodology, S.M.F., A.L. and R.L.S.; Writing—original draft, S.M.F., A.L., M.L. and R.L.S.; Writing—review & editing, S.M.F., A.L., M.L. and R.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Research Council of Norway, project number 302774. The APC was funded by Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Pilot study: complete search strategy for one database. As part of the pilot study, we searched Education Source via EBSCOhost on 22 January 2022 with the following search terms:

| Search Number | Terms | Results |

| 1 | “Teach*” | n = 1,564,372 |

| 2 | (“Critical Thinking” OR “Thinking critical*” OR “CT” OR “critical*” OR “reflect* thinking”) | n = 165,096 |

| 3 | (“education sustain* development” OR “education for sustain* OR “sustain* education” OR “sustain* development education” OR “ESD”) | n = 7711 |

| 4 | (“Primary School*” OR “Primary Educ*” OR “Elementary School*” OR “Elementary Educ*” OR “Secondary School*” OR “Secondary Educ*” OR “Middle School*” OR “Middle Educ*” OR “Junior High School*” OR “Junior High Educ*”) | n = 339,762 |

| 5 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 AND S4 | n = 45 |

| * means that it will search for all the words that are composed with the identified word. For example, Educ* could mean Education, Educational, … | ||

Appendix B

Pilot study: complete search strategy for one database. As part of the pilot study, we searched Education Source via EBSCOhost on 17 November 2021 with the following search terms:

| Search Number | Terms | Results |

| 1 | (“Teacher*” OR “Teaching” OR “Teach”) | n = 1,684,915 |

| 2 | (“critical thinking” OR “think* critically” OR “critical reflection*” OR “reflecting critically”) | n = 23,050 |

| 3 | (“Primary School*” OR “Primary Educ*” OR “Elementary School*” OR “Elementary Educ*” OR “Secondary School*” OR “Secondary Educ*” OR “Middle School*” OR “Middle Educ*” OR “Junior High School*” OR “Junior High Educ*”) | n = 470,413 |

| 4 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 | n = 2360 |

| * means that it will search for all the words that are composed with the identified word. For example, Educ* could mean Education, Educational, … | ||

Appendix C

All 43 articles included in the systematic review, sorted by article category. PR—Peer Reviewed; J—Journal article, TM—article in Teacher’s Magazine, CP—Conference Proceedings article, BC—Book Chapter, I—Implicit CT, E—Explicit CT (highlighted—make up the n = 19 that were further analysed).

| Author (Article Categorization) | Year of Publication | Country of Investigation | Type of Publication | Implicit or Explicit CT |

| Intervention studies (n = 11) | ||||

| Ampuero et al. (2015) | 2015 | Chile | PRJ | E |

| Angelaina and Jimoyiannis (2012) | 2012 | Greece | PRJ | I |

| Barakiti and Bokolas (2014) | 2014 | Greece | * CP | E |

| Bloxsome et al. (2017) | 2017 | Australia | PRJ | I |

| Christenson (2004) | 2004 | USA | PRJ | I |

| Contrafatto et al. (2015) | 2015 | Peru | PRJ | I |

| Jackson et al. (1997) | 1997 | USA | PRJ | E |

| Muthersbaugh et al. (2014) | 2014 | USA | PRJ | E |

| Pedretti (1999) | 1999 | Canada | PRJ | E |

| Proulx (2004) | 2004 | Canada | PRTM | E |

| Utzschneider and Pruneau (2010) | 2010 | Canada | PRJ | I |

| Module-based articles (n = 23) | ||||

| Bardsley and Bardsley (2007) | 2007 | Australia | PRJ | I |

| Berge et al. (2014) | 2014 | USA | PRJ | I |

| Boomershine (1994) | 1994 | USA | * TM | I |

| Bradfield (2020) | 2020 | Australia | * TM | I |

| Britton et al. (2010) | 2010 | USA, Mexico | * TM | I |

| Brown and Golden (2017) | 2017 | USA | PRTM | E |

| Childers et al. (2016) | 2016 | USA | PRTM | I |

| Deaton and Cook (2012) | 2012 | USA | PRJ | E |

| Garzón et al. (2019) | 2019 | Spain | CP | E |

| Gille (2008) | 2008 | France | * BC | I |

| Goodwin (2014) | 2014 | Canada | PRTM | E |

| Heller (1997) | 1997 | USA | PRJ | E |

| Jeffrey et al. (2016) | 2016 | USA | PRJ | I |

| Karvankova et al. (2020) | 2020 | The Czech Republic | PRJ | E |

| Kitagawa et al. (2018) | 2018 | USA | PRJ | I |

| Kruger (2020) | 2020 | South Africa | PRJ | I |

| Krupa and Knowles (2010) | 2010 | USA | * TM | I |

| Pokrandt (2010) | 2010 | USA | PRJ | I |

| Poleski (2017) | 2017 | USA | PRJ | I |

| Rahman et al. (2019) | 2019 | Indonesia | * CP | E |

| Robinson and Mangold (2013) | 2013 | USA | * CP | I |

| Sperry (2020) | 2020 | USA | PRJ | E |

| Weiland (2011) | 2011 | USA | PRTM | I |

| Other (n = 9) | ||||

| Blatt (2015) (Teacher interviews) | 2015 | USA | PR | E |

| Costa and Martins (2011) (Guidelines) | 2011 | Portugal | * CP | I |

| Fleming and Billman (2005) (Guidelines) | 2005 | USA | PRJ | I |

| Hasslöf and Malmberg (2015) (Teacher interviews) | 2015 | Sweden | PRJ | E |

| Hicks (1991) (Commentary) | 1991 | England | PRJ | E |

| Kumar and Fritzer (1994) (Commentary) | 1994 | USA | * J | E |

| McKeown (2013) (Guidelines) | 2013 | USA | PRJ | E |

| Pajari and Harmoinen (2019) (Teacher interviews) | 2019 | Finland | PRJ | I |

| Sukmawan and Setyowati (2017) (Teacher interviews) | 2017 | Indonesia | PRJ | I |

| * No information about peer review process available. | ||||

References

- Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Waddington, D. I., Wade, C. A., & Persson, T. (2015). Strategies for teaching students to think critically: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 85(2), 275–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliakbari, M., & Sadeghdaghighi, A. (2013). Teachers’ perception of the barriers to critical thinking. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 70, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampuero, D., Miranda, C. E., Delgado, L. E., Goyen, S., & Weaver, S. (2015). Empathy and critical thinking: Primary students solving local environmental problems through outdoor learning. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 15(1), 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E., Reffhaug, M., & Jegstad, K. (2025). ‘It’s not rocket science. It’s all about facilitation and imagination’: Teachers’ perceptions of how to facilitate critical thinking in primary education. In K. M. Jegstad, T. Bjørkvold, & E. Andersson-Bakken (Eds.), Enacting critical thinking in primary school. Perspectives from the classroom. Scandinavian University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R. (2015). Critical thinking and/or argumentation in higher education. In M. Davies, & R. Barnett (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of critical thinking in higher education (pp. 49–62). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Angelaina, S., & Jimoyiannis, A. (2012). Analysing students’ engagement and learning presence in an educational blog community. Educational Media International, 49(3), 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakiti, K., & Bokolas, V. (2014, March 10–12). Critical thinking and methodology of problem-based learning: Building wiki tools bridges. INTED2014 Proceedings. 8th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Bardsley, D. K., & Bardsley, A. M. (2007). A constructivist approach to climate change teaching and learning. Geographical Research, 45(4), 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, S. L. (2022). Critical education for sustainable development: Exploring the conception of criticality in the context of global and Vietnamese policy discourse. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 54(5), 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, N., Thompson, D. D., Ingram, C., & Pierce, C. (2014). Engineering Design and Effect. Science Scope, 38(3), 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjønnes, B. (2017). Bærekraftig utvikling: Utforskende arbeidsmåter. Bedre Skole, 29(2), 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt, E. N. (2015). An investigation of the goals for an environmental science course: Teacher and student perspectives. Environmental Education Research, 21(5), 710–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloxsome, B., Van Gent, D., Stalker, L., & Ferguson, B. (2017). A collaborative approach to school community engagement with a local CCS project. Energy Procedia, 114, 7295–7309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomershine, S. (1994). Mining Your Own Business—And Other Environmental Activities. Science Scope, 18, 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, A. (2016). Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: A structured methodological review. Systematic Reviews, 5(74), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A., Noyes, J., Flemming, K., Moore, G., Tunçalp, Ö., & Shakibazadeh, E. (2019). Formulating questions to explore complex interventions within qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Global Health, 4, e001107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, A., Papaioannou, D., & Sutton, A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bradfield, K. (2020). Reading with an ecocritical lens: Deeper and more critical thinking with children’s literature. Practical Literacy: The Early and Primary Years, 25(2), 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Britton, S., Tippins, D., Cajigal, A., Cox, M., Cole, G., Vazquez, M., Tippins, D., Guzman, A., & Guzman, A. (2010). The Adventures of the Gray Whale: An Integrated Approach to Learning about the Long Migration. Science Scope, 33(8), 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A., & Golden, B. (2017). Climate change photosynthesis misleading information: Navigating critical thinking and scientific reasoning in the classroom. Science Scope, 41(2), 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbules, N. C., & Berk, R. (1999). Critical thinking and critical pedagogy: Relations, differences, and limits. In T. S. Popkewitz, & L. Fendler (Eds.), Critical theories in education: Changing terrains of knowledge and politics (pp. 45–66). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Childers, G., Wolfe, K., Dupree, A., Young, S., Caver, J., Quintanilla, R., & Thornton, L. (2016). Sculpting the barnyard gene pool: Immersing students in the science and engineering of chicken genetics and hatcheries. The Science Teacher, 83(7), 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, S. C., & Cheah, P. K. (2009). Teacher perceptions of critical thinking among students and its influence on higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 20(2), 198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson, M. A. (2004). Teaching multiple perspectives on environmental issues in elementary classrooms: A story of teacher inquiry. The journal of environmental education, 35(4), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, P., & Papanikolaou, A. (2023). Examining Pre-Service Teachers’ Critical Thinking Competences within the Framework of Education for Sustainable Development: A Qualitative Analysis. Education Sciences, 13(12), 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contrafatto, M., Thomson, I., & Monk, E. A. (2015). Peru, mountains and los niños: Dialogic action, accounting and sustainable transformation. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 33, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C., & Martins, I. P. (2011, March 7–9). Education for sustainable development: Contributions to a science curriculum for primary education. INTED2011 Proceedings. 5th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Covidence. (n.d.). Covidence systematic review software, veritas health innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Davies, M. (2015). A model of critical thinking in higher education. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Volume 30, pp. 41–92). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, M., & Barnett, R. (2015). Introduction. In M. Davies, & R. Barnett (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of critical thinking in higher education (pp. 1–25). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Davies, M. J., & Willing, L. (2023). An examination of teachers’ beliefs about critical thinking in New Zealand high schools. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 48, 101280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, C. C. M., & Cook, M. (2012). Using role-play and case study to promote student research on environmental science. Science Activities, 49(3), 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, R. (2013). Critical thinking across the curriculum: The Wisdom CTAC program. Inquiry: Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines, 28(2), 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, R. H. (1987). Critical thinking and the curriculum. In Thinking skills instruction: Concepts and techniques (pp. 40–48). Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Ennis, R. H. (2015). Critical thinking: A streamline conception. In M. Davies, & R. Barnett (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of critical thinking in higher education (pp. 31–48). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPOC. (2020). EPOC Qualitative Evidence Synthesis: Protocol and review template. Version 1.1. EPOC Resources for review authors. Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Available online: http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors.

- EU. (2016). A new skills agenda for Europe: Working together to strengthen human capital, employability and competitiveness. European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. The Delphi report. The California Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Facione, P. A. (2016). Cultivating a positive critical thinking mindset. Measured Reasons LLC: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Facione, P. A. (2000). The disposition toward critical thinking: Its character, measurement, and relationship to critical thinking skill. Informal Logic, 20(1), 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, L. C., & Billman, L. W. (2005). Are You Sure We’re Supposed to Be Reading These Books for Our Project? Middle School Journal, 36, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (1973). Education for critical consciousness. Seabury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garzón, A., Montes, M., & Cara, B. (2019, November 11–13). Environmental education and mathematics to raising awareness in the young population about the use of plastic. ICERI2019 Proceedings. 2nd annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville, Spain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, B., Hopwood, B., & O’Brien, G. (2002). Environment, economy and society: Fitting them together into sustainable development. Sustainable Development, 10(2), 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, H. (2008). Environmental education from the perspective of sustainable development: A teaching resource kit for dryland countries. In C. Lee, & T. Schaaf (Eds.), The future of drylands. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, C. (2014). Fracking: Unlocking the Great Debate. Green Teacher. Education for Planet Earth, 104, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena, M., & Wilson, K. (2021). Scaffolding students’ critical thinking: A process not an end game. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 41, 100848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallingfors, H., & Åström Elmersjö, H. (2025). Guarding the boundaries: A Swedish policy debate about geography and education for sustainable development. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasslöf, H., & Malmberg, C. (2015). Critical thinking as room for subjectification in education for sustainable development. Environmental Education Research, 21, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M. F. (1997). Reading and writing about the environment: Visions of the year 2000. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 40, 332–341. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, D. (1991). Preparing for the millennium: Reflections on the need for futures education. Futures, 23, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J., & Thomas, J. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (2nd ed.). Wiley. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781119536604 (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Hitchcock, D. (2020). Critical Thinking. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/critical-thinking (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Howe, E. R. (2004). Canadian and Japanese teachers’ conceptions of critical thinking: A comparative study. Teachers and Teaching, 10(5), 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N. L., Cerrato, M. L., & Elliot, N. (1997). Geography and fieldwork at the secondary school level: An investigation of anthropogenic litter on an estuarine shoreline. Journal of Geography, 96, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, T. D., McCollough, C. A., & Moore, K. (2016). Crabby interactions: Fifth graders explore human impact on the blue crab population. Science and Children, 53(7), 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B. B., & Schnack, K. (2006). The action competence approach in environmental education: Reprinted from Environmental Education Research (1997) 3(2), pp. 163–178. Environmental Education Research, 12(3–4), 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, L. D. (1991). Teaching intellectual autonomy: The failure of the critical thinking movement. Educational Theories, 41(4), 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvankova, P., Popjakova, D., & Mintalova, T. (2020). Using the ‘new age Atlantis’ case study for global education components of geography lessons across lower secondary schools in Czechia. Review of International Geographical Education Online, 10(2), 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, L., Pombo, E., & Davis, T. (2018). Plastic pollution. Science and Children, 55(7), 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, J. (2020). Self-directed education in two transformative pro-environmental initiatives within the eco-schools programme: A South African case study. Education as Change, 24(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupa, K. M., & Knowles, C. C. (2010). Scientific Inquiry, Technology, and Nature. Learning & Leading with Technology, 38, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, D. (2019). Critical thinking as discourse. Human Development, 62(3), 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D., & Fritzer, P. (1994). Critical thinking assessment in a science and social studies context. American Secondary Education, 22(3), 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, E. R. (2011). Critical thinking: A literature review. Pearson’s Research Reports, 6(1), 40–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, E., Kobrin, J., Sato, E., & Weegar, J. (2017). Examining the constructs assessed by published tests of critical thinking. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W. (2025). The future of competence building for sustainable development. In W. Leal Filho, B. Rebelatto, A. Annelin, & G. Boström (Eds.), Competence building in sustainable development (pp. 423–434). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, M. A., & de la Pava, L. (2017). Conceptions of critical thinking from university EFL teachers. English Language Teaching, 10(7), 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, R. (2013). Teaching for a brighter more sustainable future. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 49(1), 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education and Research [Kunnskapsdepartementet]. (2017). Overordnet del—Verdier og prinsipper for grunnopplæringen. Fastsatt som forskrift ved kongelig resolusjon. Læreplanverket for Kunnskapsløftet 2020. Ministry of Education and Research [Kunnskapsdepartementet].

- Miri, B., David, B. C., & Uri, Z. (2007). Purposely teaching for the promotion of higher-order thinking skills: A case of critical thinking. Research in Science Education, 37(4), 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkebye, E., & Gericke, N. (2022). Primary school teachers’ understanding of critical thinking in the context of education for sustainable development. In B. Puig, & M. P. Jimenez-Aleixandre (Eds.), Critical thinking in biology and environmental education: Facing challenges in a post-truth world (pp. 249–266). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Munkebye, E., Scheie, E., Gabrielsen, A., Jordet, A., Misund, S., Nergård, T., & Øyehaug, A. (2020). Interdisciplinary primary school curriculum units for sustainable development. Environmental Education Research, 26(6), 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthersbaugh, D., Kern, A. L., & Charvoz, R. (2014). Impact through images: Exploring student understanding of environmental science through integrated place-based lessons in the elementary classroom. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 28(3), 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noddings, N. (1995). Teaching themes of care. Phi Delta Kappa, 76, 675. [Google Scholar]

- Oner, D., & Aggul, Y. G. (2023). Critical thinking for teachers. In N. Rezaei (Ed.), Integrated education and learning (Vol. 13). Integrated Science. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, J. (2008). Values and democracy in education for sustainable development—Contributions from Swedish research. Liber Förlag. [Google Scholar]

- Pajari, K., & Harmoinen, S. (2019). Teachers’ perceptions of consumer education in primary schools in Finland. Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education, 10(2), 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedretti, E. (1999). Decision making and STS education: Exploring scientific knowledge and social responsibility in schools and science centers through an issues-based approach. School Science and Mathematics, 99(4), 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrandt, R. (2010). What is green? The Technology Teacher, 69, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Poleski, M. (2017). A Lesson Plan for Advanced Placement Human Geography®: A Site Location Exercise for New Businesses. The Geography Teacher, 14(3), 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA. (n.d.). Available online: http://prisma-statement.org (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Proulx, G. (2004). Integrating scientific method & critical thinking in classroom debates on environmental issues. The American Biology Teacher, 66(1), 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, D. F., Chandra, D. T., & Anwar, S. (2019,Development of an integrated science teaching material oriented ability to argue for junior high school student. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1157(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reffhaug, M. B. A., & Lysgaard, J. A. (2024). Conceptualisations of ‘critical thinking’ in environmental and sustainability education. Environmental Education Research, 30(9), 1519–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. (2018). Learning to transform the world: Key competencies in Education for Sustainable De-velopment. Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development, 39(1), 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann, M., Mindt, L., & Gardiner, S. (2017). Education for sustainable development goals—Learning objectives. UNESCO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S. L., & Mangold, J. A. (2013, November 15–21). Implementing engineering and sustainability curriculum in K-12 education. ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L. (2017). The role of critical thinking in science education. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(20), 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Scheie, E., Berglund, T., Munkebye, E., Staberg, R. L., & Gericke, N. (2022). Læreplananalyse av kritisk tenking og bærekraftig utvikling i norsk læreplan. Acta Didactica Norden, 16(2), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, H. (1988). Educating reason: Rationality, critical thinking, and education. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sinakou, E., Boeve-de Pauw, J., & Van Petegem, P. (2019). Exploring the concept of sustainable development within education for sustainable development: Implications for ESD research and practice. Environment Development Sustainability, 21(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperry, S. (2020). Briefing: Project Look Sharp’s decoding media constructions and substantiality. Journal of Sustainability Education, 23, 298–308. [Google Scholar]

- Sukmawan, S., & Setyowati, L. (2017). Environmental messages as found in Indonesian folklore and its relation to foreign language classroom. Arab World English Journal, 8, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taimur, S., & Sattar, H. (2020). Education for Sustainable Development and Critical Thinking Competency. In W. Leal Filho, A. Azul, L. Brandli, P. Özuyar, & T. Wall (Eds.), Quality Education. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K., & Lok, B. (2015). Teaching critical thinking: An operational framework. In M. Davies, & R. Barnett (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of critical thinking in higher education (pp. 93–105). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndahl, K. L., & Stentoft, D. (2020). Thinking critically about critical thinking and problem-based learning in higher education: A scoping review. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 14(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. (2011). Education for sustainable development: An expert review of processes and learning. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Timm, J. M., & Barth, M. (2020). Making education for sustainable development happen in elementary schools: The role of teachers. Environmental Education Research, 27(1), 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. (1992, June 3–14). Agenda 21. United Nations Conference on Environment & Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- UN. (2005). UN general assembly. 2005 world summit outcome resolution/adopted by the general assembly, 24 October 2005, A/RES/60/1. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/44168a910.html (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- UNESCO. (2017). Education for sustainable development goals: Learning objectives. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]