1. Introduction

Inclusive education, which promotes the full participation of all students regardless of ability, has become a central goal in contemporary educational discourse. Physical Education (PE), a subject inherently centered on social interaction and cooperation, holds significant potential for promoting inclusion and social justice. Inclusion is not a static goal but a continuous process of problem-solving and professional responsiveness on the part of teachers. It requires educators to observe, reflect, and adapt their instructional practices in response to diverse learner needs.

Reflection has been widely recognized as a core component of professional development and educational transformation (

Kolb, 1984;

Schön, 1983). Teachers who engage in reflective practices are better equipped to evaluate their assumptions, confront challenges, and improve their instructional methods (

Bourner, 2003;

Davis, 2003). However, in Physical Education specifically, the research on reflective thinking remains limited (

Ballard, 2006;

Standal & Moe, 2013). Most studies indicate that PE teachers tend to adopt direct teaching models and emphasize technical outcomes, often neglecting the cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions of learning (

Kirk, 2009;

Dania et al., 2016).

Despite the theoretical emphasis on reflection, there is insufficient empirical exploration of how PE teachers can be supported to progress from technical to critical reflection—particularly through structured professional development programs that promote inclusive values. This is a critical gap, especially in light of increasing classroom diversity and the need for pedagogical approaches that foster equity, respect, and active citizenship.

The present study addresses this gap by investigating whether a professional development program based on Paralympic values can enhance reflective thinking among PE teachers and promote inclusive teaching practices. Specifically, thisstudy examines (a) whether PE teachers can shift their reflective thinking from technical to critical levels and (b) whether reflective practices can foster inclusive classroom environments. By focusing on journal writing and guided reflection, this study contributes to a better understanding of how PE can serve as a platform for inclusive education and professional growth.

2. Literature Review

In light of the increasing emphasis on inclusive education and the identified lack of empirical research on reflective thinking in Physical Education, the following review presents the theoretical and empirical foundations that underpin this study. It summarizes key contributions to the conceptualization of reflection, the role of reflective journals, the development of critical reflection, and how these dimensions relate specifically to Physical Education teaching. This framework provides the conceptual basis for designing and interpreting the current intervention.

2.1. Theoretical Framework of Reflection

Reflection has long been regarded as a core component of professional growth and teacher development. Rather than simply describing or recalling experiences, reflection entails a deliberate cognitive process aimed at evaluating teaching practices, questioning assumptions, and informing future action (

Dewey, 1933;

Kolb, 1984;

Schön, 1983). As

Davis (

2003) and

Bourner (

2003) argue, reflection is a fundamental aspect of lifelong learning and serves as a foundation for continued pedagogical improvement.

Pollard (

2008) emphasizes that reflective teachers engage in objectifying their teaching experiences to enact meaningful changes. This is aligned with Dewey’s definition of reflective thought, which involves persistent, active inquiry into one’s own beliefs and practices (

Dewey, 1933).

Hatton and Smith (

1995) add that reflective teaching is a form of problem-solving that involves careful organization of thoughts and informed decision-making. Similarly,

Rodgers (

2002) identifies four essential characteristics of reflection, including its systematic, communal, and transformative nature. These perspectives suggest that effective reflection requires structure, collaboration, and a commitment to self-improvement.

Despite this consensus,

Corcoran and Leahy (

2003) caution that much of what is called reflection may merely be retrospective description. Genuine reflection, they argue, entails a reasoned and evidence-based analysis of experience.

Leahy and Corcoran (

1996) distinguish this from superficial recall by highlighting the intentional examination of personal and contextual factors. This analytical view of reflection is further reinforced by

Reynolds (

2011), who asserts that without leading to action, reflection remains incomplete.

2.2. Reflective Journals

Reflective journal writing (RJW) is widely recognized as a practical method for facilitating structured reflection in educational contexts (

Moon, 2006). Rather than starting with citations, it is important to establish that RJW promotes critical self-examination and supports the articulation of teaching experiences. According to

Thorpe (

2004), journals are written records that help teachers and students reflect on experiences and improve self-awareness. Similarly,

Cowan (

2014) emphasizes the importance of posing meaningful questions as a starting point for critical thought.

Several studies affirm the effectiveness of RJW in professional learning.

Garmon (

1998) and

Good and Whang (

2002) highlight its role in supporting independent learning and emotional engagement.

Farrell (

2003) points out that journaling enables the documentation of teaching challenges and achievements, encouraging critical examination of pedagogical choices.

Wallin and Adawi (

2018) also note that RJW promotes self-regulated learning and contributes to ongoing assessment.

Recent findings by

Batman and Saka (

2021) show that micro-reflective techniques, such as journaling, enhance core professional skills among pre-service teachers. The literature suggests that RJW not only deepens self-reflection but also provides evidence of reflective growth. Furthermore,

Bean and Zulich (

1989) argue that journal writing nurtures professional autonomy and enriches instructional approaches.

2.3. Critical Reflection

The concept of reflection has evolved into more nuanced models that differentiate between levels of engagement.

van Manen (

1977) proposed a tripartite framework: Technical Reflection, which emphasizes efficiency in achieving objectives; Practical Reflection, which considers values underlying teaching goals; and Critical Reflection, which integrates ethical and social justice dimensions.

Zeichner and Liston (

1987) further expand on this by situating reflection within institutional and societal contexts.

At the critical level, reflection becomes a tool for challenging inequities and envisioning transformative change.

Johns (

2000) underscores that critical reflection allows educators to reconcile contradictions between ideals and practice.

Boyd and Fales (

1983) and

Baumgartner (

2001) describe this as transformative learning, capable of reshaping beliefs and fostering personal and professional growth.

In educational practice, this progression from technical to critical reflection is pivotal for inclusive and equitable teaching. As noted by

Dania et al. (

2016), the classification into TR, PR, and CR provides a structured lens through which reflective depth can be assessed and developed. This theoretical grounding is central to the current study.

2.4. Reflective Thinking in Physical Education

Although reflection has been widely explored in general education, fewer studies focus specifically on reflective thinking within Physical Education (PE).

Ballard (

2006) notes this gap and emphasizes the need for targeted research in this field. According to

Placek and Smyth (

1995), preservice PE teachers often exhibit low levels of reflection during their training, with limited improvement over time.

Innovative methods to foster reflective thinking include the use of metaphors (

Carlson, 2001). These approaches encourage deeper engagement and self-awareness among pre-service teachers. Studies by

Attard and Armour (

2005) and

Attard (

2007) also underline the significance of peer collaboration in overcoming professional isolation and sustaining reflective growth.

The timing and duration of reflective interventions are crucial.

Senne and Rikard (

2002) emphasize that short-term efforts yield limited results, while extended programs are more effective in fostering lasting change. Finally, the dominance of direct instruction in PE (

Kirk, 2009) highlights the urgency of promoting reflective and inclusive pedagogies, especially in response to diverse student needs (

Dania et al., 2016).

This review reveals both the importance of reflection in teaching and the limited empirical focus on PE-specific reflective practices. The present study addresses this gap by exploring how a structured, values-based professional development program can enhance reflective thinking among in-service PE teachers.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative educational intervention approach, specifically in the form of action research. The research design included the development and implementation of a structured intervention in authentic school settings, with the explicit aim of enhancing inclusive education. The participating teachers were not passive subjects of observation but active agents of change and professional development (reflective practitioners). The process integrated elements of reflection through the systematic use of reflective journal writing, while data collection aimed to evaluate both the transformation of teaching practices and the overall impact of the intervention.

This study followed a six-phase action research cycle: (1) problem identification, (2) intervention planning, (3) action implementation, (4) data collection, (5) reflection, and (6) redesign or further planning. The core problem identified was the presence of heterogeneous classrooms, including students with diverse educational and social needs, highlighting the need to promote inclusive education. The intervention was thus designed to train and support Physical Education Teachers (PETs) in adopting inclusive pedagogical strategies and values, particularly those aligned with the Paralympic values.

The research was conducted over ten weeks and involved 20 PE lessons. Two lessons per week (each 45 min) were taught in accordance with the official curriculum, enriched by inclusive practices and Paralympic values. The intervention included theoretical and practical training for the participating teachers, delivered by the researcher and a critical friend. The critical friend was a former Physical Education consultant with experience in doctoral-level research and extensive educational expertise. Their role included supporting teachers, providing feedback, and conducting non-participatory observation during lesson implementation.

This study involved seven in-service Physical Education Teachers working in primary schools in the province of Corinthia, Greece. The selection followed convenience sampling based on the teachers’ availability, willingness to participate, and continuity in the same school for the duration of the program. Although convenience sampling limits the generalizability of findings, this is consistent with the methodological orientation of qualitative research, which prioritizes depth and context over statistical representativeness. The term study group is used here in accordance with qualitative research conventions (

Cohen et al., 2018).

All participating teachers had substantial teaching experience (ranging from 12 to 28 years) and were aged between 46 and 55.According to previous research, experience is a vital component in the development of critical thinking (

Standal & Moe, 2013;

Yüksel & Tuncel, 2017), as well as in the successful completion of reflective journals (

Tsangaridou & O’Sullivan, 1997). They were permanent staff at their schools, which ensured continuity and the capacity for critical reflection. The selection of this small group is methodologically justified in action research, where collaborative inquiry and contextual understanding are prioritized (

McNiff & Whitehead, 2011;

Stringer, 2014).

The study employed methodological triangulation using three data collection tools: (1) semi-structured interviews, (2) reflective journals, and (3) non-participatory observation.

Interviews were conducted at the beginning and end of the intervention (14 total; two per participant). Each lasted approximately 30 min and followed a semi-structured format, enabling both consistency and openness.

Reflective journals were completed by the teachers at the end of each of the 20 lessons, using the DIEP model (Describe, Interpret, Evaluate, Plan) (

Redmond, 2006). The journals included five open-ended questions inspired by the DIEP model:

- (1)

What was the main theme of today’s lesson?

- (2)

If you could change something about the lesson, what would it be?

- (3)

Do you believe that students developed any cognitive or motor skills during the lesson?

- (4)

What do you consider to be the strongest aspect of this lesson?

- (5)

Do you think the lesson content was meaningful and interesting for the students? Please explain why or why not.

Responses were categorized based on van Manen’s levels of reflection (TR, PR, CR), as refined by

Dania et al. (

2016).

Observation was conducted by the critical friend, who applied non-participatory observation techniques focused on the implementation fidelity of lesson plans and inclusive practices.

Ethical research conduct was upheld: PETs provided informed consent, and parental consent was obtained for all students. The research was approved by the Greek Institute of Educational Policy (Approval ID: 40/03-10-2019), and the final authorization for its implementation in schools was issued by the Hellenic Ministry of Education under the decision Φ15/113151/167978/Δ1/29-10-2019. Furthermore, the study received ethical clearance from the Ethics Committee of the University of the Peloponnese. All necessary ethical protocols were followed. Participation was voluntary, with the right to withdraw at any stage. Teachers were anonymized using pseudonyms to protect personal data. No audiovisual materials were collected to ensure student privacy. The students’ parents provided written consent allowing the researcher and the critical friend to observe their children’s Physical Education lessons.

Data analysis followed a content analysis approach. Journal entries were analyzed by two independent coders (the researcher and the critical friend), and each response was coded using the categories TR, PR, and CR. An initial inter-rater agreement of 85% was achieved. In cases of disagreement, coders discussed and reached full consensus on final categorization. The process adhered to best practices in qualitative research (

Denzin, 2012;

Flick, 2007).

The analysis procedure for interviews followed inductive analysis principles based on Grounded Theory (

Strauss & Corbin, 1990), employing

Gioia et al.’s (

2013) coding model: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. Each step was documented to ensure transparency and methodological consistency.

Field notes were taken systematically by the critical friend during classroom observations. Although video or audio recordings were not used (due to ethical considerations), detailed written records were maintained to capture implementation dynamics and classroom interactions. The absence of audiovisual documentation is acknowledged as a limitation but was offset by the consistency and triangulation of multiple qualitative sources.

The content of the intervention followed the official national curriculum and included basketball and football modules, enriched with values-based activities drawn from Paralympic education. Materials included the following: structured lesson plans, instructional guides, discussion prompts on inclusion, and reflection tasks. Both individual support and group support were provided to teachers during the implementation phase.

This methodological framework supports the study’s objective of examining whether and how PE teachers develop reflective thinking through a targeted, inclusive educational intervention grounded in action research.

In terms of content, the didactical lessons implemented during the intervention were based on the Teaching Games for Understanding (TGfU) approach, which emphasizes tactical awareness and understanding of gameplay over the flawless execution of isolated motor skills, the “Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility” model developed by Hellison, as well as the principles of “fair play” and “cooperative learning.” Activities incorporated into the introductory and concluding parts of the lessons were drawn from previous Paralympic education programs implemented in Greek schools, such as “Olympic Education,” “Kallipateira,” “Paralympic Games: From 1960 to 2004,” and “Paralympic Day.”

No content in this article was generated using AI, and no data were collected or analyzed through AI-based tools.

4. Results

The findings are presented according to the three research tools used: interviews, reflective journals, and observation. The structure follows the principles of triangulation and highlights convergence across data sources.

4.1. Interview Analysis

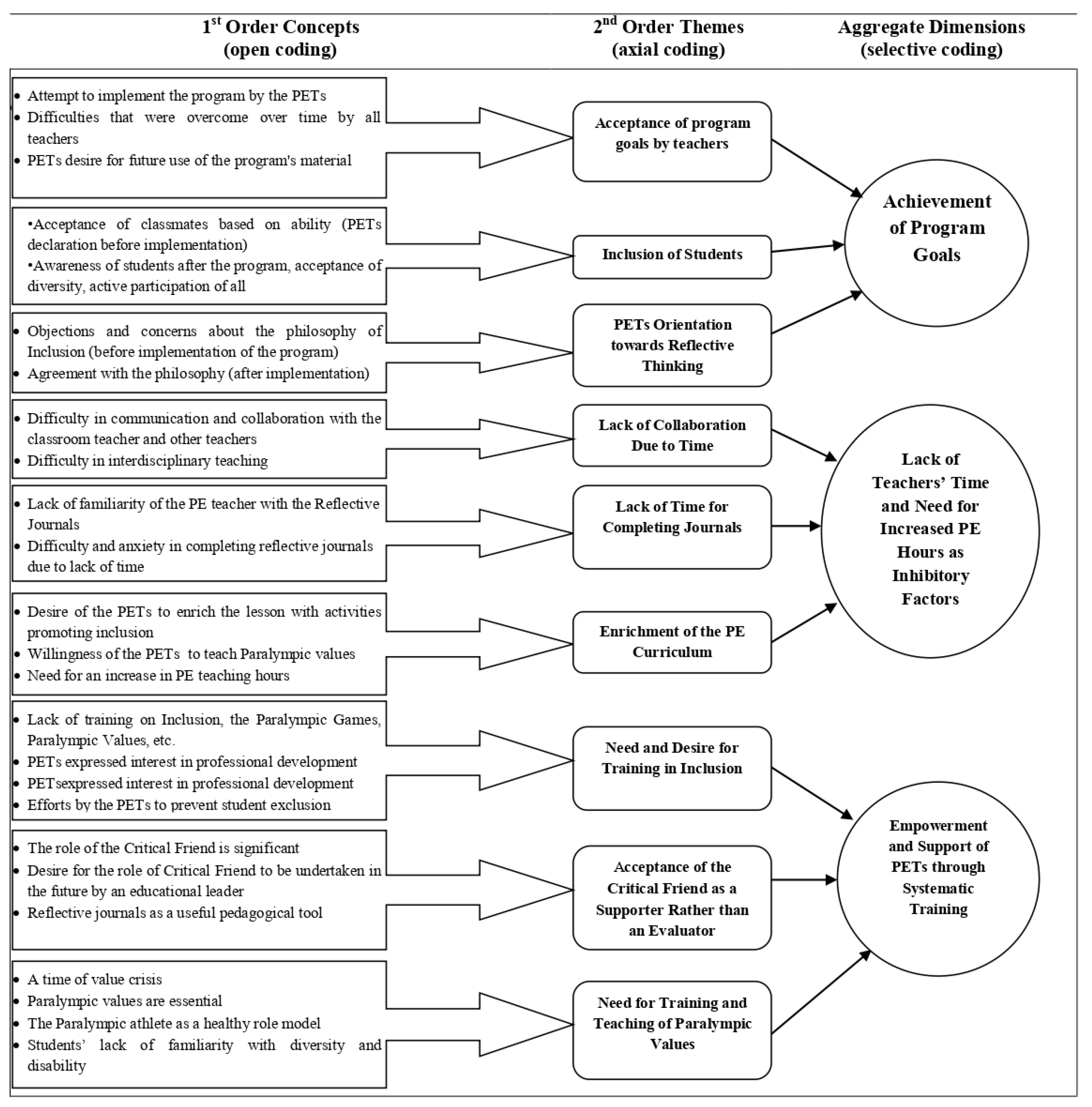

The interview data were analyzed using “inductive analysis” and the principles of “Grounded Theory” (

Strauss & Corbin, 1990), which is particularly suitable for shedding light on areas where existing knowledge is limited (

Turner & Astin, 2021). The analysis was carried out through “coding procedures” following the stages proposed by

Gioia et al. (

2013): in the first stage (1st order concepts), “open coding” was used to identify initial categories within a large volume of qualitative data. In the second stage (2nd order themes), “axial coding” was applied to examine similarities and differences across categories, assigning conceptual labels. Finally, in the Aggregate Dimensions stage (“selective coding”), a data structure was constructed—an analytical framework that served as the foundation for the overall research interpretation.

The interview findings indicated that the PETs attempted to implement the program, encountered only minimal difficulties, and progressively embraced the program’s objectives. In the beginning of the program, they expressed reservations regarding the philosophy of inclusion, noting that students tended to prefer teammates who could lead them to victory. However, by the end of the program, students had become more sensitized, showed acceptance toward their peers’ diversity, and expressed a clear desire for inclusion. The program’s goals were successfully achieved. As Joanna remarked: “You wouldn’t see a child left out. Even some girls who previously didn’t participate in basketball or football were now engaged in the game—and everyone took part!” (translated from Greek).

It was also revealed that PETs have limited time available for discussion and collaboration with other teachers. Regarding the reflective journals, they appeared unfamiliar with the tool, and although they found it useful, it caused anxiety—primarily due to lack of time. They expressed a strong interest in receiving training on inclusion and emphasized that the two weekly hours allocated to Physical Education are insufficient. They had not received any training on Paralympic values, Paralympic Games, or in general, on strategies for promoting inclusion within Physical Education. The Paralympic values were viewed as essential content for schools, and Physical Education was identified as an ideal context for their teaching. The Paralympic athlete was described as a healthy role model for students.

The role of the Critical Friend in the research was significant. All participants considered this support essential and expressed a desire for such a supportive role to be assumed in the future by a qualified educational leader.

Teachers also reported that students are not familiar with disability and highlighted the broader need for awareness and engagement with diversity. These values must be promoted through both teacher and student education and training. In conclusion, PETs require sustained support and structured professional development to reinforce their role.

With respect to the research questions, the interviews suggest that an inclusive learning environment was established and that teachers progressed toward reflective thinking. A summary of the interview coding process is presented in “

Figure 1. Stages of Interview coding.”

4.2. Reflective Journal Analysis

The journals were completed by the teachers immediately following the conclusion of each lesson. The Physical Education Teachers (PETs) responded to five questions per journal entry, across a total of 20 lessons, resulting in 100 responses per teacher throughout the program. The three levels of teacher reflection were first introduced by

van Manen (

1977) and have since been further developed and analyzed by numerous scholars (

Ballard, 2006;

Zeichner & Liston, 1987). In this study, we adopt the reflection stages proposed by

Dania et al. (

2016).

At the first level, Technical Reflection (TR), the teacher concentrates on evaluating the means rather than the ends. The focus is on the teacher’s role in ensuring the effectiveness and efficiency of instruction in achieving predetermined objectives. The teacher follows the lesson plans consistently and precisely. The second level, Practical Reflection (PR), involves analyzing and experimenting with the underlying logic of teaching processes, goals, and outcomes while also attempting to clarify the fundamental principles and values that guide student learning. The third level, Critical Reflection (CR), addresses the broader purposes of education within social, political, and ethical contexts, emphasizing values such as meritocracy, justice, and democracy. The ultimate aim of this highest level of reflection is to promote inclusive education free from bias.

According to the principles of action research, the lessons are divided into two cycles: the first cycle includes lessons 1 to 10, and the second cycle comprises lessons 11 to 20. Below is a synthesis of the PETs’ development across both cycles, supported by representative quotes and corresponding graphs.

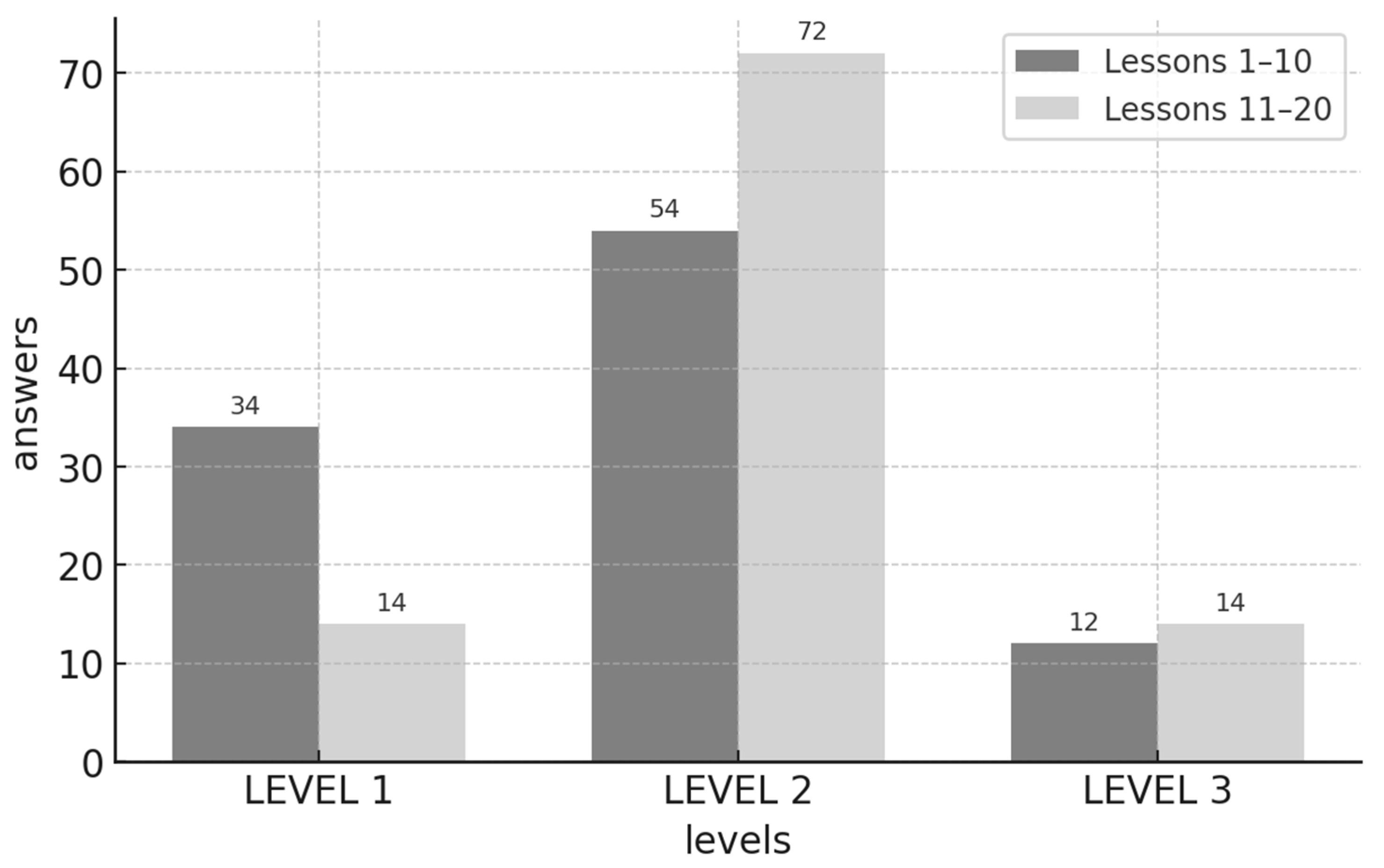

4.2.1. Daphne

The female PET, referred to as “Daphne”, demonstrated a predominance of Practical Reflection (PR) during lessons 1–10. Specifically, 34% (17 responses) were categorized as technical reflection (TR), 54% (27 responses) as Practical Reflection, and 12% (6 responses) as Critical Reflection (CR). In lessons 11–20, her TR responses decreased to 14% (7), PR increased to 72% (36), and CR rose slightly to 14% (7). This shift indicates a progression toward deeper reflective thinking. Daphne’s prior involvement in inclusive education initiatives (e.g., Olympic Education, Kalypatira, Paralympic Day), as reported in the interview, likely contributed to her initial inclination toward higher levels of reflection. The reduction in technical responses and the increase in practical and critical ones suggest a development in her pedagogical stance. A representative response appears in the penultimate lesson (19), where the teacher states the following: “Through this process, students will eventually become more cooperative, learn to follow and apply rules, and make fair decisions” (translation from Greek). These changes are visualized in “

Figure 2: Daphne’s answers,” which presents the distribution of her responses across the two phases of the program.

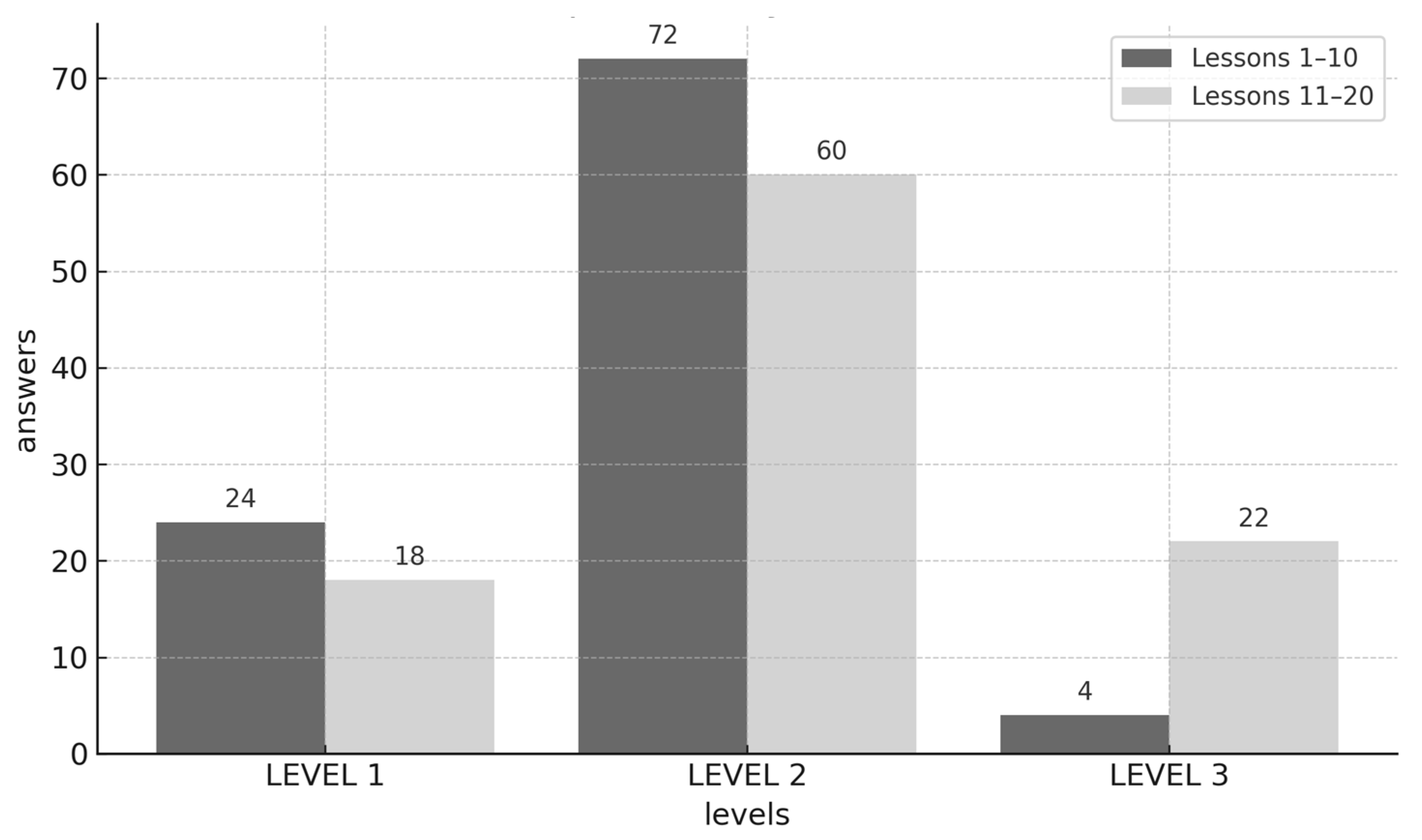

4.2.2. Betty

Betty demonstrated a predominantly practical mode of reflection (Level 2) from the beginning of the program. In the first cycle of lessons (1–10), 24% of her responses fell under technical reflection (Level 1), 72% aligned with practical reflection (Level 2), and only 4% (2 responses) demonstrated critical reflection (Level 3), with the latter appearing for the first time in lesson 10. In the second cycle (lessons 11–20), a shift is observed: Level 1 responses decrease to 18%, Level 2 to 60% (30 responses), while Level 3 responses increase significantly to 22% (11 responses). This trend suggests a gradual evolution from technical to critical reflection, although practical reflection remains dominant. A characteristic example is her statement in lesson 18: “a climate of democratic processes was created.” This highlights her emerging capacity for critical engagement. In conclusion, although Betty’s thinking remains largely at the practical level, the progressive reduction in technical responses in favor of critical reflection is noteworthy. The distribution of responses across reflection levels is illustrated in “

Figure 3: Betty’s answers.”

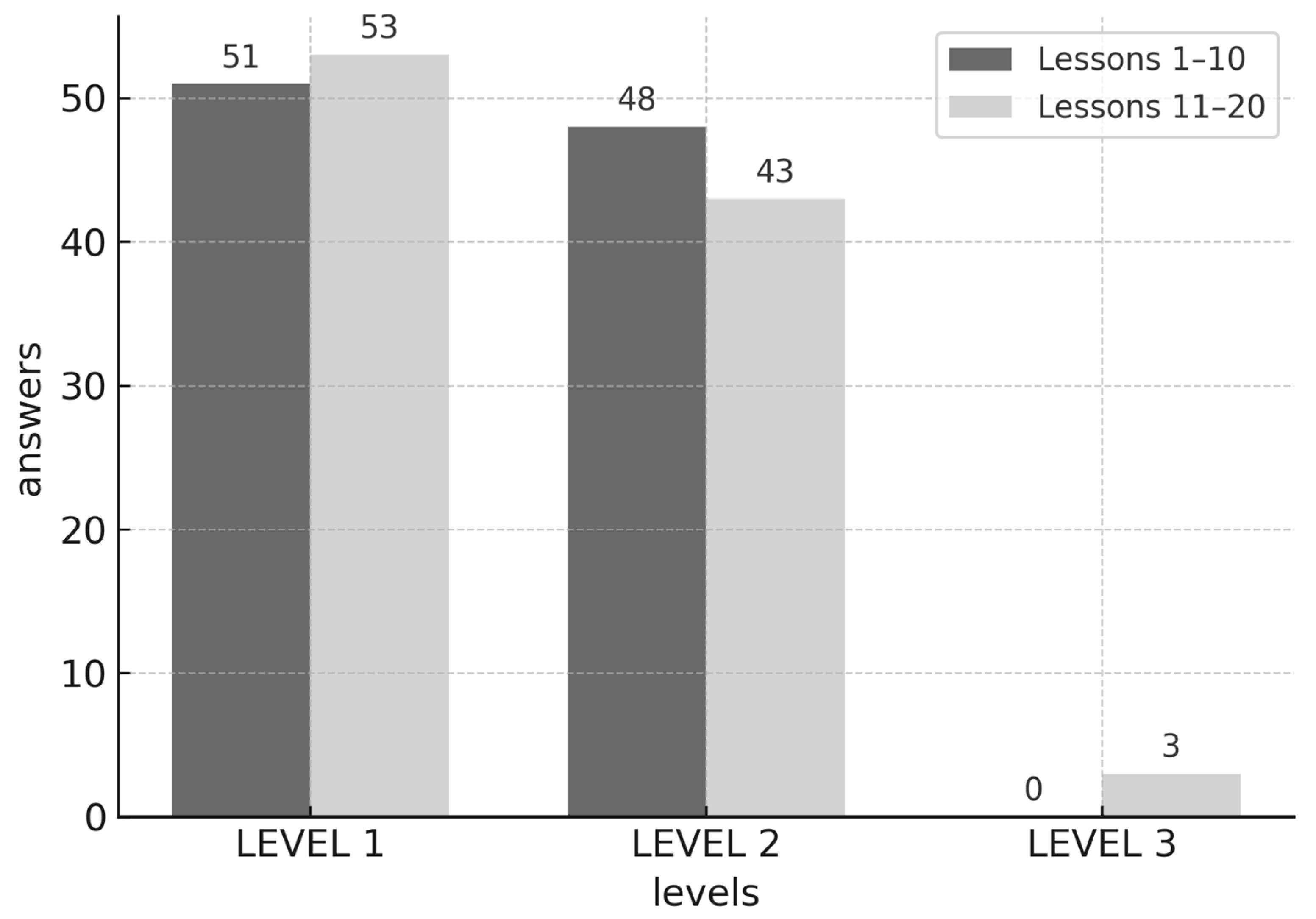

4.2.3. Fani

A female PET, referred to as “Fani,” demonstrated a consistent pattern of reflective thinking across both cycles of the program. In the first cycle, her responses were almost evenly distributed between technical and practical reflection, with no instances of critical reflection (Level 3). In the second cycle (lessons 11–20), the proportion of Level 1 responses slightly increased to 53%, while Level 2 responses decreased to 44%. These findings suggest that the teacher’s reflective stance remained largely stable over time. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that some responses in the second cycle were categorized at the level of critical reflection (Level 3), indicating isolated instances of deeper engagement. A likely explanation for the limited progression lies in a contextual constraint: the teacher reported time pressure due to immediate relocation to another school following each lesson, which hindered the timely completion of the journals. This issue is substantiated by both interview data and observational notes. The distribution of responses across the three levels of reflection in both cycles is presented in “

Figure 4: Fani’s answers.”

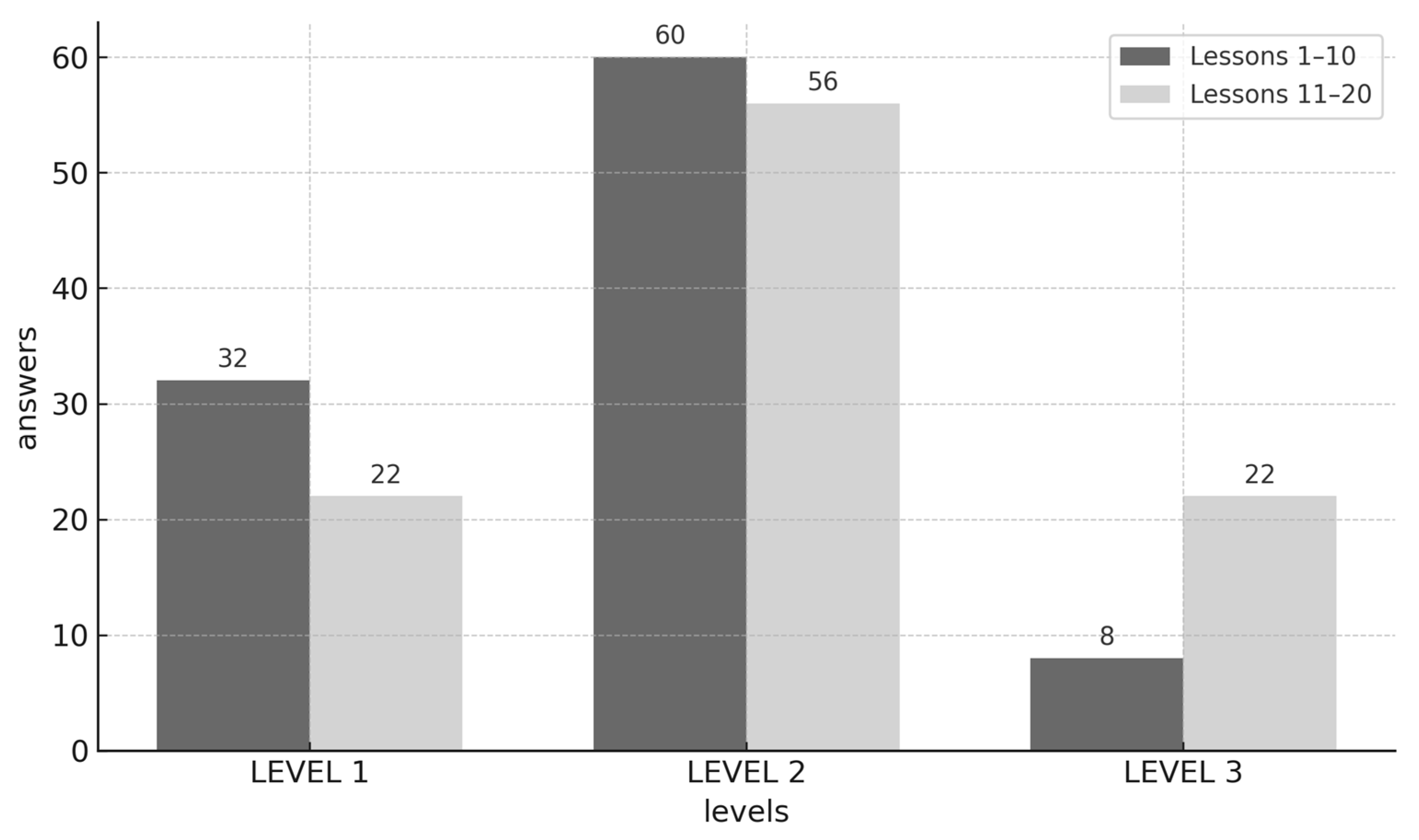

4.2.4. Sotiris

A male PET, referred to as “Sotiris,” demonstrated a reflective profile predominantly situated at the level of practical reflection (Level 2) across both phases of the program. In the first cycle (lessons 1–10), 32% of his responses were categorized as technical reflection (Level 1), 60% as practical (Level 2), and only 8% as critical reflection (Level 3). In the second cycle (lessons 11–20), there is a noticeable decline in Level 1 responses to 22%, with Level 2 slightly reduced to 56%, and Level 3 responses increasing markedly to 22%. This shift suggests a move away from merely applying instructional procedures toward a more critical, evaluative stance. A representative example is found in lesson 19, where he stated the following: “I believe they developed the ability to build the rules of a fair game step by step and to understand their necessity. This will help them in the future to respect these rules more- whether they concern a game or social life itself.” The distribution of responses across the three levels of reflection is presented in “

Figure 5: Sotiris’s answers.”

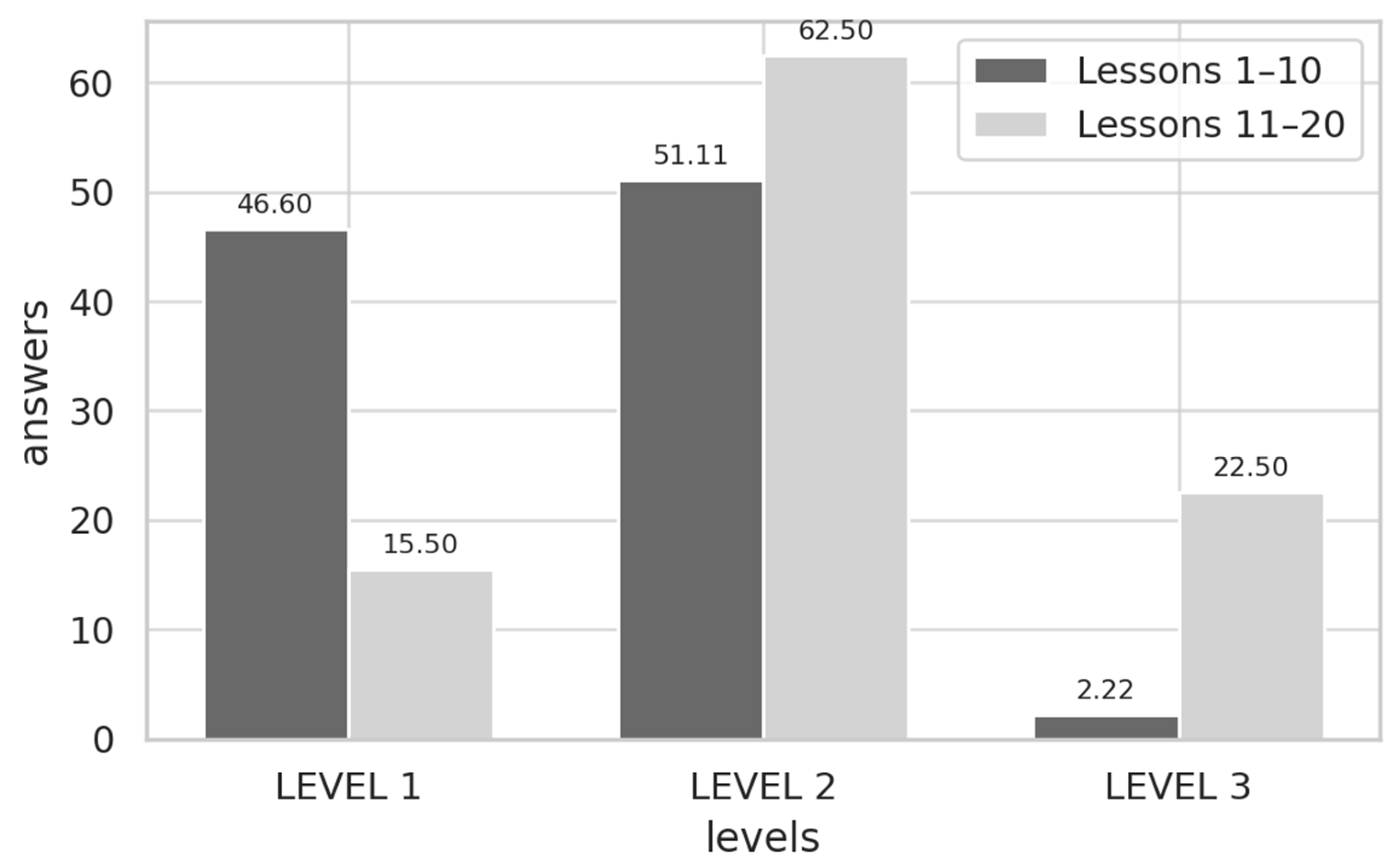

4.2.5. Thomas

A male PET, referred to as “Thomas,” exhibited a transition from technical to critical reflection over the course of the program. In the first cycle (lessons 1–10), he completed 45 out of 50 journal entries. His responses were divided between technical and practical reflection. The use of decimal values occurs because some questions were left unanswered. Thomas had time constraints due to his additional role as assistant principal at the school, which explains the missing responses in some of the journals, as noted in both the interview and the observation. In the second cycle (lessons 11–20), he answered 40 out of 50 questions. Responses at Level 1 dropped markedly to 15% (6 responses), Level 2 increased to 62.5% (25 responses), and Level 3 rose to 22.5% (9 responses), indicating a substantial shift toward more critical thinking. A representative response appears in lesson 19: “Students were supported in understanding the importance of cooperation and respect for the opponent.”In summary, the teacher demonstrated a clear reduction in technical reflection, a consolidation of practical thinking, and a notable enhancement in critical reflection. The distribution of responses across reflection levels is presented in “

Figure 6: Thomas’s answers.”

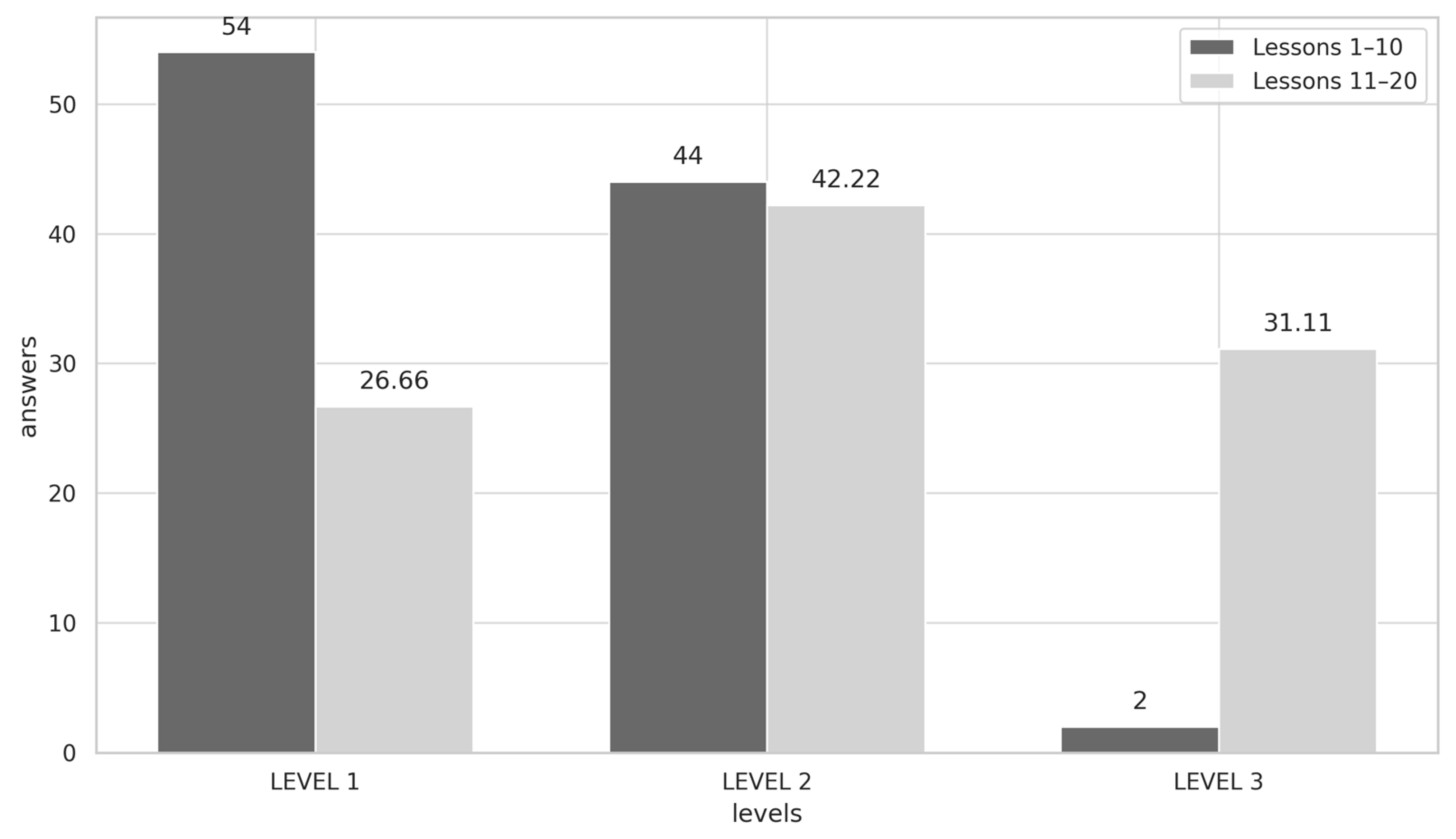

4.2.6. Akis

A male PET, referred to as “Akis,” exhibited a notable shift in his reflective thinking throughout the program. His responses at the level of critical reflection (Level 3) increased significantly—from just 2% in the first cycle (lessons 1–10) to 31% in the second cycle (lessons 11–20)—indicating a clear progression toward deeper critical engagement. A representative response in the final lesson illustrates this transformation: “This will help students in matters of respecting diversity and promoting the inclusion of all individuals in society.” This evolution in reflective practice is visually presented in “

Figure 7: Akis’s answers.”

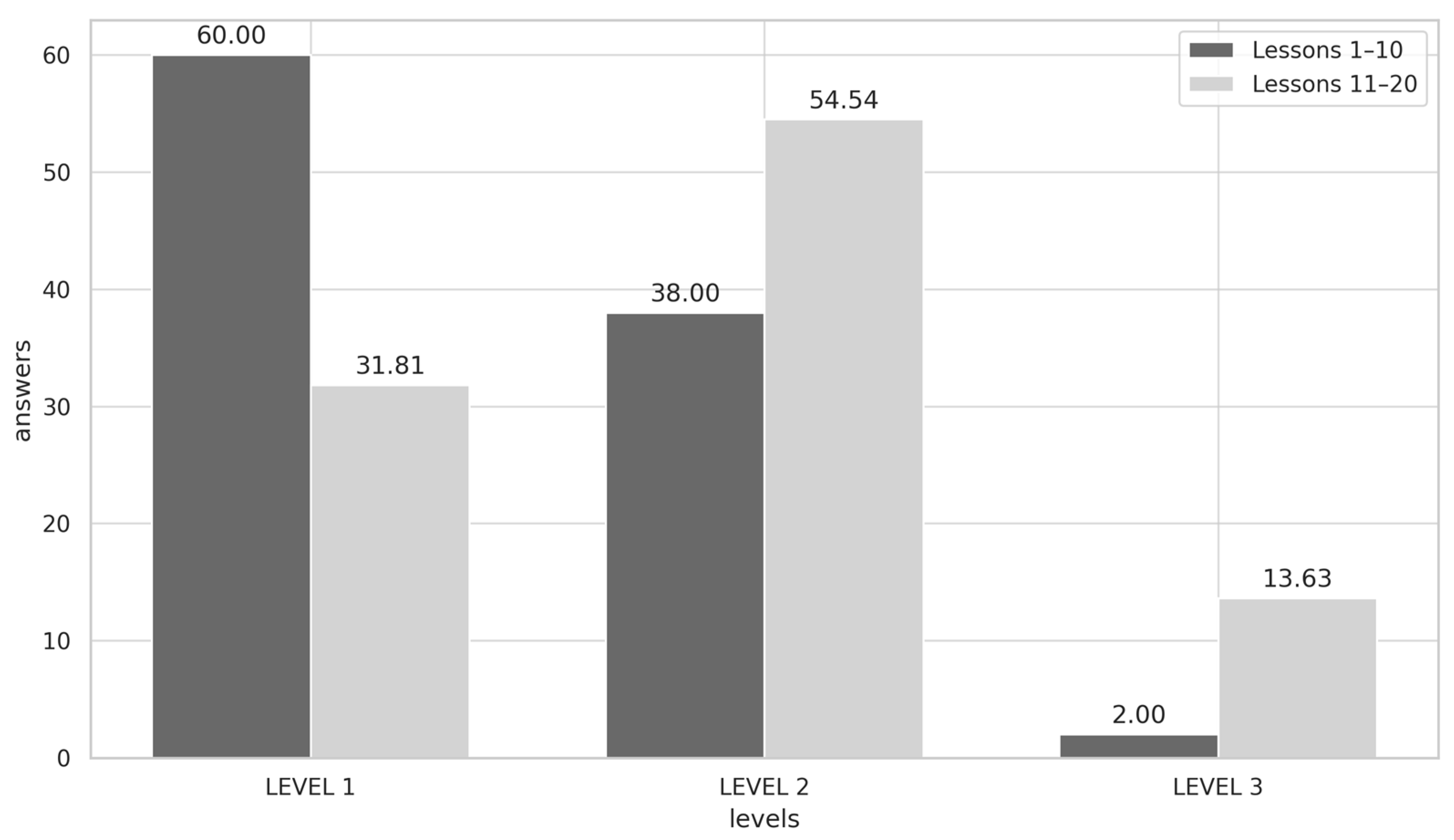

4.2.7. Joanna

A female PET, referred to as “Joanna,” demonstrated a clear shift in her reflective thinking over the course of the program. She significantly reduced her responses at the level of technical reflection (Level 1), progressively transitioning toward practical (Level 2) and critical reflection (Level 3). A representative response appears in lesson 18, where she noted the following: “During the lesson, honesty and self-discipline were cultivated.” The progression in her reflective practice is depicted in “

Figure 8: Joanna’s answers.”

An analysis of the reflective journal data across participants reveals varying degrees of development in reflective thinking. Most PETs demonstrated a clear progression from technical to practical and, in several cases, to critical reflection. For example, Akis showed the most significant transformation, increasing his Level 3 (CR) responses from 2% to 31%. Similarly, Thomas and Sotiris exhibited strong growth in critical reflection, especially in the second cycle of lessons.

In contrast, Fani maintained a stable but limited reflective pattern, with most responses concentrated at the technical and practical levels and minimal movement toward critical reflection. This stagnation may be attributed to contextual limitations, such as time constraints and difficulty completing the journals. Joanna and Betty also demonstrated upward movement in reflection levels, with Joanna notably reporting a change in students’ participation, reflecting a deeper pedagogical awareness.

These differences suggest that while the intervention generally promoted reflective thinking, its impact was mediated by individual factors, such as teaching experience, openness to inclusive practices, and the level of engagement with the reflective process. The consistent support of the “critical friend” emerged as a key factor in facilitating teacher development, particularly for those who initially encountered implementation challenges.

4.3. Observation Analysis

A non-participatory observation was conducted by the critical friend throughout the implementation of the program. The observation focused on specific criteria, including the fidelity to the lesson plans, classroom management, and the application of inclusive teaching strategies. Findings indicated that all participating teachers implemented the program and consistently followed the lesson plans. The teacher referred to as “Sotiris” initially experienced significant difficulties, particularly with instructional methodology and time management. The supportive role of the critical friend proved crucial in helping him overcome these challenges and complete the program successfully.

Although no direct data were collected from students, it is worth noting that observable changes were recorded in student behavior. The classroom climate progressively evolved into one that was inclusive and free from exclusionary attitudes or practices.

This triangulated presentation of findings confirms the transformative potential of structured, values-based professional development in fostering reflective teaching practices and promoting inclusion in Physical Education.

5. Discussion

The results of the study demonstrate that the participating Physical Education Teachers (PETs) exhibited notable progress in their reflective thinking, with most moving from technical to practical and critical levels of reflection, in line with van Manen’s framework and the model by

Dania et al. (

2016). The data derived from the 140 reflective journals (20 per teacher, 7 teachers) confirmed that the structured intervention enabled deepened pedagogical reflection and an evolving understanding of inclusive education. Triangulated findings from interviews and observations further validated the shifts in teachers’ thinking and practice.

One of the main contributions of this study is its evidence that a professional development program grounded in values-based content—specifically Paralympic values—can foster not only inclusive practices but also a more critical, ethical, and student-centered reflective stance among teachers. This supports earlier research emphasizing the transformative potential of reflective teaching (

Brookfield, 2017;

Zeichner & Liston, 1996).

Research conducted with prospective Physical Education teachers demonstrated that strengthening reflective thinking skills can enhance both their theoretical understanding and instructional performance (

Salman & Şenel, 2024). This suggests that teachers and students alike can better comprehend the theoretical foundations of the values being taught.

A key challenge highlighted in the study was the limited time available to teachers—particularly those with administrative responsibilities (as in the case of Thomas)—which significantly restricted their ability to engage consistently with the reflective journals. One participant, for instance, submitted journals that were either brief and superficial or entirely missing, indicating both time pressure and potentially limited appreciation of the value of reflective writing. The barrier of lack of time has also been identified as a major constraint in similar studies (

Brookfield, 2017;

Farrell, 2013;

Libatique, 2024). This aligns with previous findings noting that not all educators find reflective writing engaging or accessible (

McCormack, 2001;

O’Connell & Dyment, 2011).

In response to these barriers, future professional development initiatives should incorporate strategies to support teachers in building reflective habits. This may include allocating protected time within teachers’ schedules for reflection, offering alternative modes of reflective expression (e.g., audio logs, peer discussion), and providing mentoring support to underscore the pedagogical purpose of reflection. Embedding reflection into the teaching culture, rather than treating it as an isolated task, is essential for long-term professional growth.

Emotional intelligence has been found to be closely linked to reflective thinking. A study conducted with nursing students revealed that participants with higher emotional awareness demonstrated a more critical and transformative approach in evaluating their educational experiences (

Dogham et al., 2025). Similarly, reflective journal writing has been shown to foster growth in teachers’ reflective thinking—particularly in their ability to identify weaknesses, enhance self-awareness, and transform their instructional practices through ongoing reflection (

Abrouq, 2024a). These findings suggest that while challenges may arise during the process, reflective engagement ultimately contributes to teachers’ professional development and pedagogical evolution—an outcome also supported by the results of the present study.

In the specific context of Physical Education—where the focus often lies on physical performance and measurable skill acquisition—there is a need to reframe reflection as a means of critically interrogating not only how skills are taught but also why certain activities are prioritized and how they relate to broader educational values such as inclusion, cooperation, and ethical behavior. Reflective questions for PE teachers might include the following: “How does this activity support all learners, including those with disabilities? In what ways does my teaching promote social–emotional learning? Are students learning to respect diversity through movement-based experiences?”

The integration of Paralympic values into PE demonstrated that reflective engagement with inclusive content can alter both instructional strategies and student perceptions. Several teachers reported improved peer interaction, greater sensitivity to diversity, and a more democratic classroom atmosphere. These outcomes suggest that reflective thinking in PE can extend beyond technique and performance, toward cultivating ethically conscious and socially aware learning environments.

Overall, the findings reaffirm that reflective practice in PE is both possible and impactful when supported through structured, contextually relevant professional development. They also emphasize the importance of designing programs that not only train teachers in reflective tools like journals but also address the institutional and cultural barriers that may hinder their effective use.

Future research could consider implementing an intervention program over a longer period than the present study. Such interventions might also be conducted in secondary education settings or with younger students in lower primary school grades. Additionally, it would be valuable to shift the focus toward students and explore their perspectives on inclusive practices and reflective teaching. Finally, quantitative data collection tools could be incorporated to support a more comprehensive investigation through a mixed-methods or fully quantitative research design.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the development of reflective thinking among Physical Education Teachers (PETs) through a professional development program centered on inclusive practices and Paralympic values. The findings, drawn from 140 reflective journal entries, semi-structured interviews, and classroom observations, indicate that most participants progressed from technical to practical and, in several cases, to critical reflection. This progression aligns with

van Manen’s (

1977) and

Dania et al.’s (

2016) frameworks and confirms that structured, value-oriented interventions can effectively foster reflective teaching. The point is to use these experiences to think, reflect, and improve their lessons. Teachers of Physical Education, like other educators, must learn to be reflective practitioners and actively analyze their own practices. This is because students and colleagues will benefit from it as well as themselves as educators who must always improve their teaching (

Maksimović & Osmanović, 2018).

The study also revealed that PETs not only adopted more inclusive teaching strategies but also reported observable changes in student behavior, including greater cooperation, participation, and respect for diversity. These outcomes demonstrate that reflective engagement has the potential to transform both teaching practices and classroom culture. Recent research has also shown that reflective thinking has a favorable and significant impact on a number of characteristics of trainee teachers’ teaching attitudes, including how well they perform as Physical Education teachers, how effectively they teach and learn, and how well they cultivate a positive attitude toward their work (

Maleesha-Malkishari et al., 2023).

Despite its strengths, the study identified practical challenges, such as limited time for reflection and unfamiliarity with journaling as a method. These barriers, consistent with findings from

McCormack (

2001) and

O’Connell & Dyment (

2011), highlight the need for targeted support in future professional development programs. Specifically, initiatives should include flexible reflective tools, institutional support, and mentoring structures to sustain reflective engagement over time.

The study reinforces previous research (

Brookfield, 2017;

Zeichner & Liston, 1996) by demonstrating that reflection can be cultivated through intentional and contextually relevant training. It also expands the literature by focusing on PE—a field often underrepresented in reflective practice research—and showing that reflective thinking can support not only pedagogical improvement but also the promotion of equity and inclusion.

Teachers and students must engage in a process of reflection and problem-solving. Targeted reflective activities can foster enhanced creative problem-solving, metacognitive awareness, and improved communication skills (

Ekarina & Engliana, 2025). Such democratic problem-solving can cultivate active and socially conscious citizens.

Moreover, systematic reflective writing functions not only as a means of self-evaluation but also as a catalyst for the formation of professional identity, moral reasoning, and pedagogical insight. As

Abrouq (

2024b) notes, such practices are essential for cultivating educators with a heightened sense of ethical and social responsibility.

The present study was limited to sixth-grade primary school students and did not involve performance assessment. The research adopted a qualitative approach, with the observation focusing on students’ full participation in the lesson (i.e., inclusion), peer interaction, and the overall learning climate (creative, democratic, and interactive). The evaluation of how well students internalized the values of inclusion and diversity may be better assessed in future studies through quantitative methods, such as structured questionnaires.

Future research should explore similar interventions across different educational levels, regions, and cultural contexts. Longitudinal designs may further capture the sustainability of reflective growth.

In conclusion, this study provides empirical evidence that reflective thinking can be effectively cultivated in Physical Education through structured, inclusive, and values-based professional development. Such programs empower teachers and simultaneously contribute to the construction of equitable, inclusive, and ethically grounded educational environments. The contemporary educator must respond to the evolving needs of students and society by embracing flexibility, self-inquiry, and pedagogical transformation.