A Systematic State-of-the-Art Review of Asian Research on Principal Instructional Leadership, 1987–2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How has Asian research on instructional leadership evolved in terms of publication trajectory and geographic scope over the past 40 years?

- What analytical models have guided Asian research on instructional leadership?

- What analytical models and research methods have been used in state-of-the-art Asian studies of instructional leadership?

- What research findings can be synthesized from state-of-the-art studies of instructional leadership in Asia?

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. The PIMRS Framework

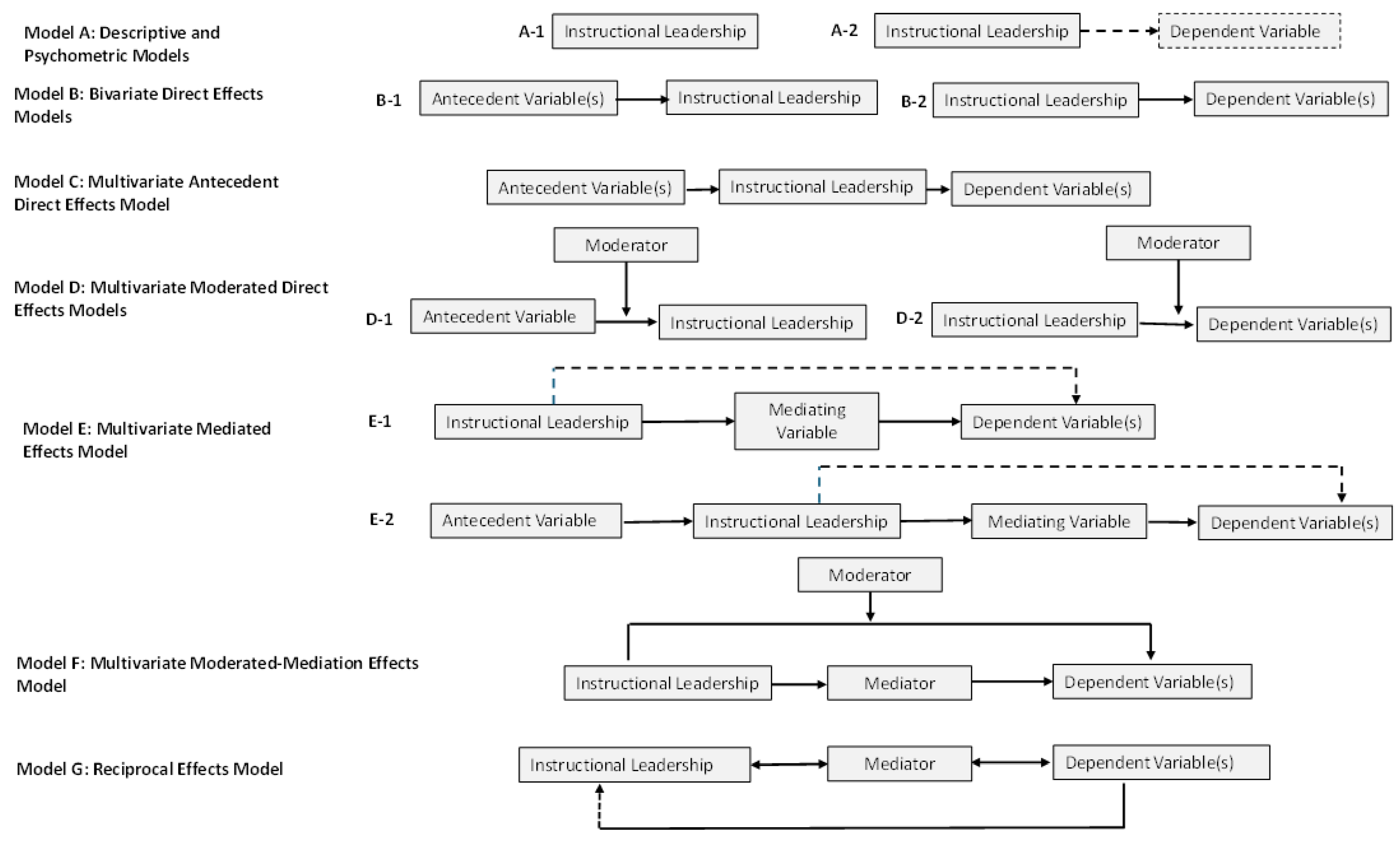

2.2. Analytical Models Used in Quantitative Studies of School Leadership

3. Materials and Methods

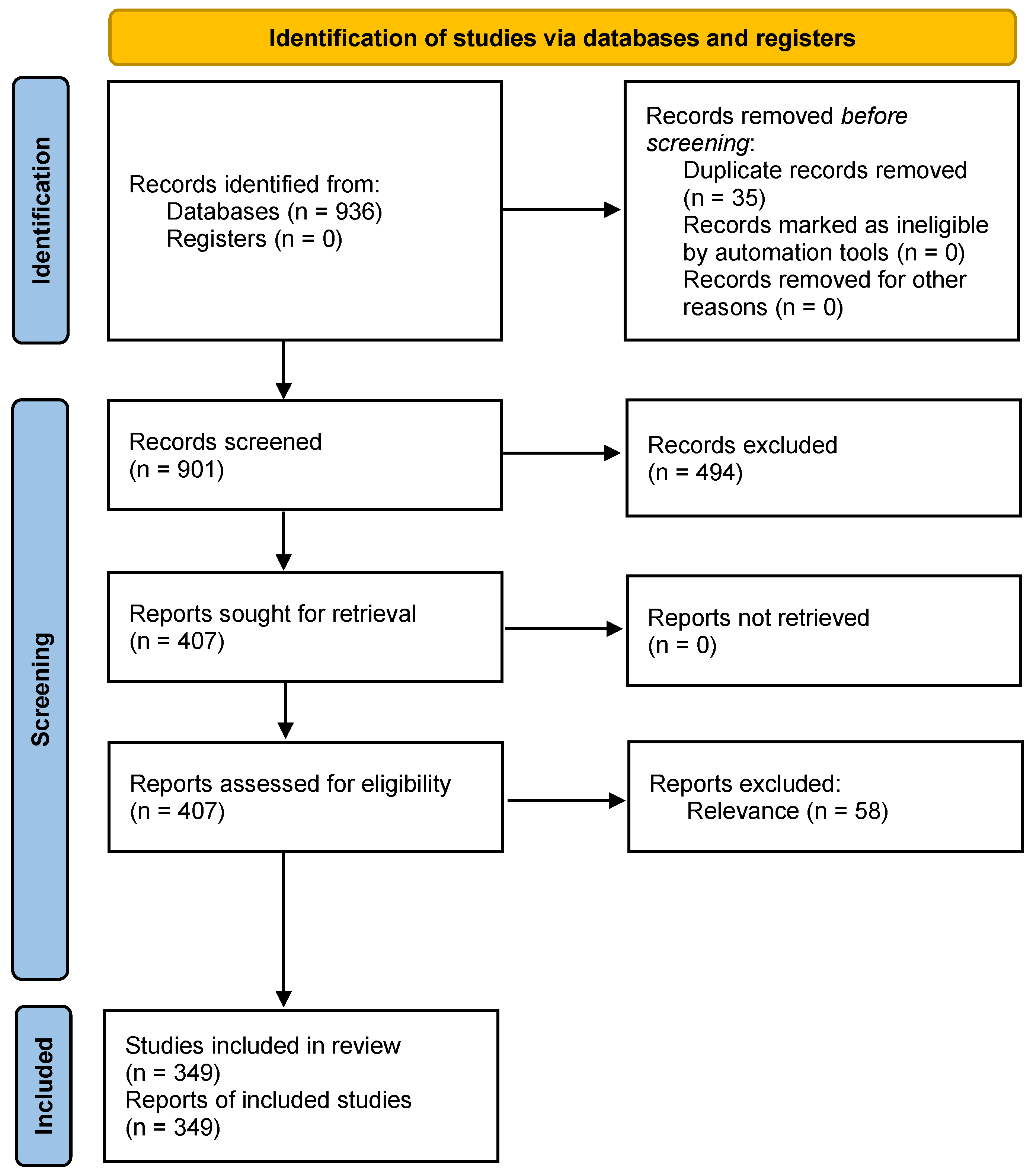

3.1. Document Identification

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Asian PIMRS Knowledge Base

4.2. Analytical Models Used in Asian Instructional Leadership Research

4.3. Analysis of State-of-the-Art PIMRS Studies from Asia

4.3.1. Methodological Characteristics of the State-of-the-Art Studies

4.3.2. Synthesis of Research Foci and Findings from State-of-the-Art PIMRS Studies of Instructional Leadership in Asia

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Interpretation of the Findings

5.3. Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguinis, H., Beaty, J. C., Boik, R. J., & Pierce, C. A. (2005). Effect size and power in assessing moderating effects of categorical variables using multiple regression: A 30-year review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanoglu, M. (2022). The role of instructional leadership in increasing teacher self-efficacy: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Education Review, 23(2), 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahdy, Y. F. H., Hallinger, P., Emam, M., Hammad, W., Alabri, K. M., & Al-Harthi, K. (2024a). Supporting teacher professional learning in Oman: The effects of principal leadership, teacher trust, and teacher agency. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 52(2), 395–416. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mahdy, Y. F. H., Hallinger, P., Omara, E., & Emam, M. (2024b). Exploring how power distance influences principal instructional leadership effects on teacher agency and classroom instruction in Oman: A moderated-mediation analysis. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 52(4), 878–900. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, P., & Lu, M. (2018). Evaluating the measuring properties of the principal instructional management rating scale in the Chinese educational system: Implications for measuring school leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(4), 624–641. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, N. A. B., Foo, S. F., Hassan, A., & Asimiran, S. (2014). Instructional leadership: Validity and reliability of PIMRS 22-item instrument. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 8(23), 200–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bajunid, I. A. (1996). Preliminary explorations of indigenous perspectives of educational management: The evolving Malaysian experience. Journal of Educational Administration, 34(5), 50–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C. A., Camburn, E., Sanders, B. R., & Sebastian, J. (2010). Developing instructional leaders: Using mixed methods to explore the black box of planned change in principals’ professional practice. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(2), 241–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, E. S., Merkebu, J., & Varpio, L. (2022). Understanding state-of-the-art literature reviews. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 14(6), 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basah, A. A., & Abdul Razak, A. Z. B. (2023). Exploring instructional leadership practises items among headmasters in public primary schools: An exploratory factor analysis. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), 8(9), e002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellibaş, M. S., Bulut, O., Hallinger, P., & Wang, W. C. (2016). Developing a validated instructional leadership profile of Turkish primary school principals. International Journal of Educational Research, 75, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellibaş, M. Ş., Kılınç, A. Ç., & Polatcan, M. (2021). The moderation role of transformational leadership in the effect of instructional leadership on teacher professional learning and instructional practice: An integrated leadership perspective. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(5), 776–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellibaş, M. Ş., Polatcan, M., & Kılınç, A. Ç. (2022). Linking instructional leadership to teacher practices: The mediating effect of shared practice and agency in learning effectiveness. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 50(5), 812–831. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutto, S., Mydin, A. A., Malik, K. H., Rind, G. M., & Tiwari, V. (2023). The impact of workplace spirituality on teachers’ critical thinking: Mediating role of instructional leadership and knowledge management. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Management, 11(4), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bossert, S. T., Dwyer, D. C., Rowan, B., & Lee, G. V. (1982). The instructional management role of the principal. Educational Administration Quarterly, 18(3), 34–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkuş, K., Güngör, T. A., & Öztürk, H. K. (2024). Predictive factors of student achievement: The role of instructional leadership, organizational trust, and teacher self-efficacy. GESJ: Education Science and Psychology, 3(72), 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, E. M. (1967). Instructional leadership: A concept re-examined. Journal of Educational Administration, 5(2), 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, E. M. (1982). Research on the school administrator: The state of the art, 1967–19801. Educational Administration Quarterly, 18(3), 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cansoy, R., & Polatcan, M. (2018). Examination of instructional leadership research in Turkey. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 10(1), 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., & Rong, J. (2023). The moderating role of teacher collegiality in the relationship between instructional leadership and teacher self-efficacy. SAGE Open, 13(4), 21582440231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S., & O’donoghue, T. (2017). Educational leadership and context: A rendering of an inseparable relationship. British Journal of Educational Studies, 65(2), 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dimmock, C., & Walker, A. (2000). Globalisation and societal culture: Redefining schooling and school leadership in the twenty-first century. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 30(3), 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorukbaşi, E., & Cansoy, R. (2024). Examining the mediating role of teacher professional learning between perceived instructional leadership and teacher instructional practices. European Journal of Education, 59, e12672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, D. A. (1979). Research on educational administration: The state-of-the-art. Educational Researcher, 8(3), 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2022). Developing robust state-of-the-art reports: Systematic literature reviews. Education in the Knowledge Society, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W., & Lu, J. (2018). Assessing instructional leadership from two mindsets in China: Power distance as a moderator. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 30(4), 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., Lu, J., & Qian, H. (2018). Principal instructional leadership: Chinese PIMRS development and validation. Chinese Education & Society, 51(5), 337–358. [Google Scholar]

- Gümüş, S., Bellibaş, M. S., Esen, M., & Gümüş, E. (2018). A systematic review of studies on leadership models in educational research from 1980 to 2014. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(1), 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gümüş, S., Hallinger, P., Cansoy, R., & Bellibaş, M. Ş. (2021). Instructional leadership in a centralized and competitive educational system: A qualitative meta-synthesis of research from Turkey. Journal of Educational Administration, 59(6), 702–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. (1983). Assessing the instructional management behavior of principals [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stanford University (United States)]. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P. (2011). A review of three decades of doctoral studies using the principal instructional management rating scale: A lens on methodological progress in educational leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47(2), 271–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., Gümüş, S., & Bellibaş, M. Ş. (2020). ‘Are principals instructional leaders yet?’ A science map of the knowledge base on instructional leadership, 1940–2018. Scientometrics, 122(3), 1629–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (1996). Reassessing the principal’s role in school effectiveness: A review of empirical research, 1980–1995. Educational Administration Quarterly, 32(1), 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (2011). Conceptual and methodological issues in studying school leadership effects as a reciprocal process. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 22(2), 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., Hosseingholizadeh, R., Hashemi, N., & Kouhsari, M. (2018). Do beliefs make a difference? Exploring how principal self-efficacy and instructional leadership impact teacher efficacy and commitment in Iran. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(5), 800–819. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P., & Kovačević, J. (2019). A bibliometric review of research on educational administration: Science mapping the literature, 1960 to 2018. Review of Educational Research, 89(3), 335–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Leithwood, K. (1996). Culture and educational administration: A case of finding out what you don’t know you don’t know. Journal of Educational Administration, 34(5), 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., Li, D., & Wang, W. C. (2016). Gender differences in instructional leadership: A meta-analytic review of studies using the Principal Instructional Management Rating Scale. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(4), 567–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Murphy, J. (1985). Assessing the instructional management behavior of principals. The Elementary School Journal, 86(2), 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Truong, T. (2016). “Above must be above, and below must be below”: Enactment of relational school leadership in Vietnam. Asia Pacific Education Review, 17(4), 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Walker, A. (2017). Leading learning in Asia–emerging empirical insights from five societies. Journal of Educational Administration, 55(2), 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., Walker, A., Nguyen, D. T. H., Truong, T., & Nguyen, T. T. (2017). Perspectives on principal instructional leadership in Vietnam: A preliminary model. Journal of Educational Administration, 55(2), 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., Walker, A., & Trung, G. T. (2015). Making sense of images of fact and fiction: A critical review of the knowledge base for school leadership in Vietnam. Journal of Educational Administration, 53(4), 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Wang, W. C. (2015). Assessing instructional leadership with the Principal Instructional Management Rating Scale. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, W., Hilal, Y. Y., & Bellibaş, M. Ş. (2024). Exploring the link between principal instructional leadership and differentiated instruction in an understudied context: The role of teacher collaboration and self-efficacy. International Journal of Educational Management, 38(4), 1184–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A., Jones, M., Adams, D., & Cheah, K. (2019). Instructional leadership in Malaysia: A review of the contemporary literature. School Leadership & Management, 39(1), 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- Heck, R., & Hallinger, P. (1999). Conceptual models, methodology, and methods for studying school leadership. In K. Leithwood, & P. Hallinger (Eds.), The 2nd handbook of research in educational administration (pp. 141–162). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Heck, R. H., & Hallinger, P. (2005). The study of educational leadership and management: Where does the field stand today? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 33(2), 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseingholizadeh, R., Amrahi, A., & El-Farr, H. (2023). Instructional leadership, and teacher’s collective efficacy, commitment, and professional learning in primary schools: A mediation model. Professional Development in Education, 49(3), 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseingholizadeh, R., Sharif, A., & Taghizadeh Kerman, N. (2021). A systematic review of conceptual models and methodologies in research on school principals in Iran. Journal of Educational Administration, 59(5), 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S. N., Muhammad, S., Omar, M. N., & Raman, A. (2020). The great challenge of Malaysian school leaders’ instructional leadership: Can it affect teachers’ functional competency across 21st century education? Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(6), 2436–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalapang, I., & Raman, A. (2020). Effect of instructional leadership, principal efficacy, teacher efficacy and school climate on students’ academic achievements. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 9(3), 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacabey, M. F., Bellibaş, M. Ş., & Adams, D. (2022). Principal leadership and teacher professional learning in Turkish schools: Examining the mediating effects of collective teacher efficacy and teacher trust. Educational Studies, 48(2), 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T., Gurr, D., Tülübaş, T., & Kanadlı, S. (2025). What factors mediate the relationship between leadership for learning and teacher professional development? Evidence from meta-analytic structural equation modelling. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 17411432241308461. [Google Scholar]

- Karakose, T., Kardas, A., Kanadlı, S., Tülübaş, T., & Yildirim, B. (2024). How collective efficacy mediates the association between principal instructional leadership and teacher self-efficacy: Findings from a meta-analytic structural equation modeling (MASEM) study. Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavitha, K. (2024). Role of principal’s instructional leadership and teacher efficacy in secondary school performance: A case study of CBSE schools in Bengaluru [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Dayananda Sagar University (India)]. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z. (2022). Examining the mediating role of school culture in the relationship between heads’ instructional leadership and students’ engagement at secondary level in Punjab, Pakistan. Bulletin of Education and Research, 44(2), 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H. C., & Lien, H. Y. (2025). Instructional leadership scale for high school principals: Development and validation. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 53(3), 484–498. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K. (2005). Understanding successful principal leadership: Progress on a broken front. Journal of Educational Administration, 43(6), 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K. (2023). The personal resources of successful leaders: A narrative review. Education Sciences, 13(9), 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Sun, J., & Schumacker, R. (2020). How school leadership influences student learning: A test of “The four paths model”. Educational Administration Quarterly, 56(4), 570–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Hallinger, P., & Ko, J. (2016). Principal leadership and school capacity effects on teacher learning in Hong Kong. International Journal of Educational Management, 30(1), 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebowitz, D. D., & Porter, L. (2019). The effect of principal behaviors on student, teacher, and school outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 785–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S. H. (2016). Amalan kepimpinan instruksional, budaya organisasi dan organisasi pembelajaran di sekolah berprestasi tinggi Malaysia (The relationship between instructional leadership, organizational culture and learning organization in high performing schools in Malaysia. Jurnal Pengurusan dan Kepimpinan Pendidikan, 30(2), 1–19. (In Malaysian). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S., & Hallinger, P. (2018). Principal instructional leadership, teacher self-efficacy, and teacher professional learning in China: Testing a mediated-effects model. Educational Administration Quarterly, 54(4), 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., & Hallinger, P. (2021). Unpacking the effects of culture on school leadership and teacher learning in China. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(2), 214–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X., & Marion, R. (2021). Exploring how instructional leadership affects teacher efficacy: A multilevel analysis. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(1), 188–207. [Google Scholar]

- Mannan, F. (2017). The relationship between women principal instructional leadership practices, teacher organizational commitment and teacher professional community practice in secondary schools in Kuala Lumpur [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Malaya (Malaysia)]. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, D. F. S. (2019). Instructional leadership. Instructional leadership and leadership for learning in schools. In T. Townsend (Ed.), Understanding theories of leading (pp. 15–48). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, D. F. S., Nguyen, T. D., Wong, K. S. B., & Choy, K. W. W. (2015). Instructional leadership practices in Singapore. School Leadership & Management, 35(4), 388–407. [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir, N., Kılınç, A. Ç., & Turan, S. (2023). Instructional leadership, power distance, teacher enthusiasm, and differentiated instruction in Turkey: Testing a multilevel moderated mediation model. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 43(3), 912–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., & Chou, R. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H. L. W., Nyeu, F. Y., & Chen, J. S. (2015). Principal instructional leadership in Taiwan: Lessons from two decades of research. Journal of Educational Administration, 53(4), 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H. L. W., Nyeu, F. Y., & Cheng, S. H. (2017). Leading school for learning: Principal practices in Taiwan. Journal of Educational Administration, 55(2), 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. K., & Lee, S. E. (2007). A study on the construct validity for the scale of instructional leadership of principals. Open Education Research, 15(2), 51–70. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitner, N. J. (1988). The study of administrator effects and effectiveness. In N. Boyan (Ed.), Handbook of research in educational administration (pp. 106–132). Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Pitner, N. J., & Hocevar, D. (1987). An empirical comparison of two-factor versus multifactor theories of principal leadership: Implications for the evaluation of school principals. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 1, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyaman, P., Hallinger, P., & Viseshsiri, P. (2017). Addressing the achievement gap: Exploring principal leadership and teacher professional learning in urban and rural primary schools in Thailand. Journal of Educational Administration, 55(6), 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, P. (2010). The relationship of instructional leadership, teachers’ organizational commitment and students’ achievement in small schools [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Universiti Sains Malaysia (Malaysia)]. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, H., Walker, A., & Li, X. (2017). The West wind vs the East wind: Instructional leadership model in China. Journal of Educational Administration, 55(2), 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A., Waqar, Y., Aslam, M., & Muhammad, Y. (2025). Rethinking instructional leadership in Pakistan’s elite schools: A call for indigenous leadership models. Journal for Social Science Archives, 3(1), 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V. M., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samichan, A., Awang, M., & Beram, S. (2021). Perbandingan model kepimpinan instruksional: Persepsi barat dan Malaysia (A comparison of instructional leadership models: The Western and Malaysian perception). Management Research Journal, 10, 94–105. (In Malaysian). [Google Scholar]

- Stemler, S. (2000). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 7(1), 17. [Google Scholar]

- Thien, L. M. (2022). Psychometric analysis of a Malay language version of the Principal Instructional Management Rating Scale. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 50(4), 711–733. [Google Scholar]

- Thien, L. M., & Adams, D. (2024). Investigating the relationships between principal instructional leadership and teachers’affective commitment through collective teacher efficacy in Malaysian rural and urban primary schools. MOJEM: Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Management, 12(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thien, L. M., Darmawan, I. N., & Adams, D. (2023). (Re) Investigating the pathways between instructional leadership, collective teacher efficacy, and teacher commitment: A multilevel analysis. International Journal of Educational Management, 37(4), 830–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thien, L. M., & Liu, P. (2024). Linear and nonlinear relationships between instructional leadership and teacher professional learning through teacher self-efficacy as a mediator: A partial least squares analysis. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, T. D., & Hallinger, P. (2017). Exploring cultural context and school leadership: Conceptualizing an indigenous model of có uy school leadership in Vietnam. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20(5), 539–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, L. D., Gumela, G., & Maulana, H. (2021). Interrater reliability: Comparison of essay tests and scoring rubrics. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1933(1), 012081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A., & Hallinger, P. (2015). A synthesis of reviews of research on principal leadership in East Asia. Journal of Educational Administration, 53(4), 554–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A., & Qian, H. (2022). Developing a model of instructional leadership in China. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 52(1), 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witziers, B., Bosker, R. J., & Krüger, M. L. (2003). Educational leadership and student achievement: The elusive search for an association. Educational Administration Quarterly, 39(3), 398–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K. C., & Cheng, K. M. (1995). Educational leadership and change: An international perspective (Vol. 1). Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi, A., Zahed Bablan, A., & Moeinikia, M. (2021). Investigating the psychometric properties of Principals’ Instructional Management Rating Scale (PIMRS-22). School Administration, 9(1), 358–337. [Google Scholar]

| Dimensions | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Research sample |

|

| Variables and measures |

|

| Data analysis |

|

| 1983–2010 | 2011–2024 | 1983–2024 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % |

| A-1: Descriptive | 9 | 19.1% | 47 | 18.3% | 56 | 18.4% |

| A-2: Psychometric | 2 | 4.3% | 7 | 2.7% | 9 | 3.0% |

| B-1: Direct Antecedent Effects | 20 | 42.6% | 30 | 11.7% | 50 | 16.4% |

| B-2: Direct Outcome Effects | 9 | 19.1% | 99 | 38.5% | 108 | 35.5% |

| C: Multivariate Antecedent Effects | 6 | 12.8% | 14 | 5.4% | 20 | 6.6% |

| D-1: Moderated Antecedent Effects | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.4% | 1 | 0.3% |

| D-2: Moderated Outcome Effects | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 2.7% | 7 | 2.3% |

| E-1: Mediated Effects | 1 | 2.1% | 42 | 16.3% | 43 | 14.1% |

| E-2: Antecedent Mediated Effects | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 2.3% | 6 | 2.0% |

| F: Moderated Mediated Effects | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 1.6% | 4 | 1.3% |

| G: Reciprocal Effects | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Total | 47 | 100% | 257 | 100% | 304 | 100% |

| Author/Year | Nation | Model | Level | Sample | Teacher n | Stat Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guo and Lu (2018) | China | D-1 | Multiple | CON | 1708 | CFA/t-test |

| Chen and Rong (2023) | China | D-2 | Middle | SNRS | 1498 | CFA; SEM |

| Mannan (2017) | Malay | D-2/E-1 | Secondary | SNRS | 357 | MR |

| Thien and Adams (2024) | Malay | D-2/E-1 | Primary | SNRS | 728 | SEM |

| Bellibaş et al. (2021) | Turkey | E-1 | Multiple | SNRS | 350 | CFA/SEM |

| Dorukbaşi and Cansoy (2024) | Turkey | E-1 | Multiple | CON | 385 | SEM |

| Hammad et al. (2024) | Oman | E-1 | Multiple | CON | 496 | CFA; SEM |

| Hosseingholizadeh et al. (2023) | Iran | E-1 | Primary | CON | 886 | CFA; SEM |

| Karacabey et al. (2022) | Turkey | E-1 | Multiple | CON | 1200 | CFA; SEM |

| Khan (2022) | Pakistan | E-1 | Secondary | SRS | 1016 | CFA; SEM |

| Ma and Marion (2021) | China | E-1 | Middle | CON | 714 | HLM |

| Thien et al. (2023) | Malay | E-1 | Primary | CON | 1328 | MSEM |

| Thien and Liu (2024) | Malay | E-1 | Multiple | CON | 355 | CFA; SEM |

| Hallinger et al. (2018) | Iran | E-2 | Primary | SNRS | 345 | CFA/SEM |

| Kavitha (2024) | India | E-2 | High School | SNRS | 4300 | CFA; SEM |

| Liu and Hallinger (2018) | China | E-2 | Middle | SRS | 3414 | MSEM |

| Al-Mahdy et al. (2024b) | Oman | F | Middle | RS | 464 | CFA; SEM |

| Bellibaş et al. (2021) | Turkey | F | Multiple | SRS | 616 | CFA; SEM |

| Liu and Hallinger (2021) | China | F | Multiple | SNRS | 1194 | CFA; SEM |

| Özdemir et al. (2023) | Turkey | F | Secondary | SNRS | 772 | CFA; MSEM |

| Author(s)/Year/Model | Model | Antecedent Variable | Moderator Variable | Ind. Variable | Mediating Variable | Dependent Variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guo and Lu (2018) | D-1 | Culture PD * | Role Set | PIMRS | ||

| Chen and Rong (2023) | D-2 | Collegial * | Full Mod. | TSE | ||

| Mannan (2017) | D-2/E-1 | Tch demog * | Part Med * | PLC * | Commit | |

| Thien and Adams (2024) | D-2/E-1 | Urban/Rural | Part Med * | CTE * | Commit | |

| Bellibaş et al. (2022) | E-1 | Full Med * | SP/Agency * | Instruction | ||

| Dorukbaşi and Cansoy (2024) | E-1 | Part Med * | TPL * | Instruction | ||

| Hammad et al. (2024) | E-1 | Full Med * | Collab/TSE * | Instruction | ||

| Hosseingholizadeh et al. (2023) | E-1 | Part Med * | CTE/Commit * | TPL | ||

| Karacabey et al. (2022) | E-1 | Part Med * | Trust/CTE * | TPL | ||

| Khan (2022) | E-1 | Full Med * | SC * | St. Engage | ||

| Ma and Marion (2021) | E-1 | Part Med * | Trust * | TSE | ||

| Thien et al. (2023) | E-1 | Part Med * | CTE * | Commit | ||

| Thien and Liu (2024) | E-1 | Part Med * | TSE * | TPL | ||

| Hallinger et al. (2018) | E-2 | PSE | Part Med * | CTE | Commit | |

| Kavitha (2024) | E-2 | S-type | Part Med * | TSE * | Achievement | |

| Liu and Hallinger (2018) | E-2 | PSE | Part Med * | TSE * | TPL | |

| Al-Mahdy et al. (2024b) | F | Culture PD * | Part Med * | Agency * | Instruction | |

| Bellibaş et al. (2021) | F | Trans Ld * | Full Mod | TPL * | Instruction | |

| Liu and Hallinger (2021) | F | Culture PD * | Part Med * | TSE * | TPL | |

| Özdemir et al. (2023) | F | Culture PD * | Full Med * | Enthusiasm * | Instruction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hallinger, P.; Liu, S.; Aung, P.N. A Systematic State-of-the-Art Review of Asian Research on Principal Instructional Leadership, 1987–2024. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 817. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070817

Hallinger P, Liu S, Aung PN. A Systematic State-of-the-Art Review of Asian Research on Principal Instructional Leadership, 1987–2024. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):817. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070817

Chicago/Turabian StyleHallinger, Philip, Shengnan Liu, and Pwint Nee Aung. 2025. "A Systematic State-of-the-Art Review of Asian Research on Principal Instructional Leadership, 1987–2024" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 817. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070817

APA StyleHallinger, P., Liu, S., & Aung, P. N. (2025). A Systematic State-of-the-Art Review of Asian Research on Principal Instructional Leadership, 1987–2024. Education Sciences, 15(7), 817. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070817