Abstract

This cross-sectional study investigated the interconnected roles of university students’ mindsets (growth and fixed), perceptions of writing feedback, and academic emotion regulation in shaping self-regulated writing ability. Data were collected from 313 undergraduate students in South Korea. A serial mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro (Model 6). The results indicated that the indirect effect of a growth mindset on self-regulated writing ability via writing feedback perception was B = 0.0883, 95% CI [0.0414, 0.1489] and that via academic emotion regulation was B = 0.0724, 95% CI [0.0256, 0.1316]. In addition, a significant sequential mediation effect was identified in both mediators—writing feedback perception and academic emotion regulation—(B = 0.0215, 95% CI [0.0044, 0.0435]). The total indirect effect was B = 0.1822, 95% CI [0.1069, 0.2686], supporting a robust mediating mechanism. These findings highlight the psychological and emotional pathways through which a growth mindset facilitates writing development. Implications for writing pedagogy include the integration of feedback literacy and emotion regulation training to support learners’ self-regulated writing in higher education contexts.

1. Introduction

In an era where lifelong learning and self-directed competence are increasingly emphasized, self-regulated writing ability has emerged as a pivotal educational goal for higher education. This ability encompasses cognitive and metacognitive strategies and emotional and motivational components to empower learners to independently plan, monitor, and revise their writing (Harris, 2024; Rodriguez-Gomez et al., 2024). Writing is cognitively demanding and emotionally charged, and self-regulation in writing significantly influences learners’ academic success, persistence, and adaptability (Bai & Wang, 2023; Hwang, 2025; Karlen et al., 2021; Sun & Wang, 2020; Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994).

Recent studies have highlighted the crucial role of individual learner characteristics—such as beliefs, attitudes, and emotional competencies—in shaping writing behaviors and outcomes (Hwang, 2025; Lin et al., 2024; Mastrokoukou et al., 2024; Sun & Wang, 2020; L. S. Teng, 2024; L. S. Teng & Huang, 2019; Yang & Zhang, 2023). One particularly influential factor is the mindset (Dweck, 2006). A growth mindset—the belief that writing ability improves through effort—enhances learners’ persistence and openness to feedback (L. S. Teng, 2024). Learners with a growth mindset believe that their abilities can be improved through effort and learning, whereas those with a fixed mindset view their abilities as innate and unchangeable. Growth-minded learners are more likely to embrace challenges, persist through hurdles, and interpret feedback constructively. In contrast, fixed-minded learners commonly avoid challenges and perceive feedback as a threat to their self-worth (Haimovitz & Dweck, 2016; L. S. Teng, 2024; Waller & Papi, 2017). In the context of writing, learners’ perceptions of feedback play a critical role in influencing their engagement, revision strategies, and overall writing performance. Feedback perception refers to how learners interpret and emotionally respond to feedback from instructors or peers, directly influencing their willingness to revise and refine their writing (Ajjawi et al., 2022; Ekholm et al., 2015; He et al., 2023; Hwang, 2025; McGrath et al., 2011; Pearson, 2022; Rowe et al., 2014; Xu, 2022; Yang & Zhang, 2023; Zhu & Carless, 2018; Zumbrunn et al., 2016). Writing feedback perception, particularly when interpreted constructively, mediates learners’ engagement with revision strategies (He et al., 2023). Additionally, academic emotion regulation—the ability of learners to monitor and manage emotions such as anxiety, frustration, or motivation during academic tasks—is essential for sustaining cognitive engagement (Camacho-Morles et al., 2021; Harley et al., 2019; Karlen et al., 2021; Mastrokoukou et al., 2024; Pekrun et al., 2002; Winstone et al., 2017). Likewise, the relations among mindset, motivation, emotion, self-regulated learning, and academic performance have been studied, suggesting that the influence of mindset on academic outcomes is often indirect, working through adaptive learning behaviors (Burnette et al., 2013; Karlen et al., 2019). Building on this body of work, this study investigates the direct effect of mindset on self-regulated writing ability and the indirect pathways through which mindset could shape writing outcomes.

While numerous studies have explored the individual effects of mindset, feedback, and emotion regulation on writing-related learning and performance, few have examined how these factors interact in influencing self-regulated writing. For example, L. S. Teng and Zhang (2020) highlighted the role played by emotional and motivational dimensions in writing, and Yang and Zhang (2023) stressed the importance of understanding feedback engagement. Some more recent studies in broader learning contexts have suggested that self-regulated learning involves a dynamic interplay of cognitive, emotional, and motivational components (Esnaashari et al., 2023; Heikkinen et al., 2025); however, empirical research that applies such integrative models specifically to writing—and examines the direct and mediating roles of mindset, feedback perception, and emotion regulation—remains limited.

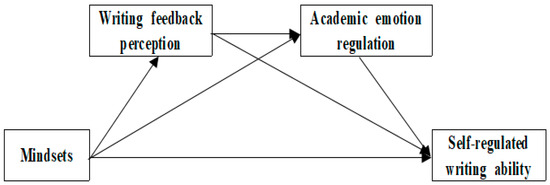

Thus, this research investigates the interconnected roles of mindset, writing feedback perception, and academic emotion regulation in predicting self-regulated writing ability among university students. Specifically, it aims to identify both the direct and indirect effects of mindset on self-regulated writing ability. To address this objective, the following research questions (RQs) and corresponding conceptual model (Figure 1) were developed:

Figure 1.

Research model.

- What are the relations among mindset, writing feedback perception, academic emotion regulation, and self-regulated writing ability among university students?

- Does writing feedback perception mediate the interplay between mindset and self-regulated writing ability?

- Does academic emotion regulation mediate the interplay between mindset and self-regulated writing ability?

- Do writing feedback perception and academic emotion regulation sequentially mediate the interplay between mindset and self-regulated writing ability?

Based on these RQs, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H1:

Mindset is significantly correlated with writing feedback perception, academic emotion regulation, and self-regulated writing ability.

H2:

Writing feedback perception mediates the interplay between mindset and self-regulated writing ability.

H3:

Academic emotion regulation mediates the interplay between mindset and self-regulated writing ability.

H4:

Writing feedback perception and academic emotion regulation sequentially mediate the interplay between mindset and self-regulated writing ability.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Mindsets and Self-Regulated Writing Ability

Mindsets play a critical role in educational contexts by influencing how learners approach learning situations, perceive their knowledge and abilities, regulate their learning, and respond to hurdles and setbacks. They influence a wide range of academic variables, encompassing emotion, motivation, strategy use, persistence in self-regulated learning (SRL), and academic achievement (Bong & Skaalvik, 2003; Dweck, 2006, 2017; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Efklides, 2011; Haimovitz & Dweck, 2016; Karlen et al., 2019, 2021; Rattan et al., 2015; Yeager & Dweck, 2020). A growth mindset—the belief that abilities can be developed through effort and learning—is closely associated with greater engagement in learning, resilience in the face of challenges, constructive interpretation of feedback, and the belief that SRL skills can improve with practice. Conversely, a fixed mindset views abilities as innate and unchangeable, often resulting in avoidance of effort, reduced persistence, fear of negative evaluation, and maladaptive learning behaviors, such as giving up when faced with difficulty (Burnette et al., 2013; Dweck, 2006; Haimovitz & Dweck, 2016; Yan et al., 2014). Although growth and fixed mindsets are conceptually distinct, they are interrelated constructs, both strongly linked to motivational, metacognitive, and emotional self-regulation. They also play a significant role in learners’ ability to adapt and cope in challenging academic situations (King et al., 2012; Ommundsen et al., 2005; Pekrun, 2006; Van der Beek et al., 2017; Yeager & Dweck, 2020). Specifically, a growth mindset is positively associated with greater enjoyment, strategic knowledge, and a stronger self-concept in SRL, all of which contribute to enhanced academic performance (Karlen et al., 2019, 2021). Furthermore, studies indicate that mindsets and SRL strategies interact synergistically: a growth mindset encourages the use of SRL strategies, whereas a fixed mindset tends to inhibit them (Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Hwang & Choi, 2024; Molden & Dweck, 2006; Ommundsen et al., 2005).

In writing contexts, a growth mindset has also been displayed to significantly influence learners’ willingness to revise, their efforts to improve writing, and their overall writing performance—effects that are mediated by SRL strategies and a self-regulatory ability (Bai & Wang, 2023; M. F. Teng et al., 2024).

2.2. Writing Feedback Perception, Academic Emotion Regulation, and Self-Regulated Writing Ability

Effective self-regulated writing necessitates not only cognitive and metacognitive approaches but also the ability to constructively process feedback and regulate academic emotions during the writing process. Learners’ perceptions of writing feedback and their capacity for emotional regulation have been identified as key contributors to writing development (Carless & Young, 2024; Cheah & Li, 2020; Hwang, 2025; Pearson, 2022; Ryan & Henderson, 2018; Winstone et al., 2017; Yang & Zhang, 2023; Zhu & Carless, 2018). In writing instruction, feedback plays a vital role in addressing writing challenges, enhancing motivation, and fostering self-regulated writing (Brown et al., 2016; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Wisniewski et al., 2020; Q. Yu & Schunn, 2023). Moreover, feedback that targets strategy enhancement or encourages self-monitoring in learning processes is effective in optimizing self-regulatory skills in language learning (Xiao & Yang, 2019), and has been demonstrated to significantly influence self-regulated writing (Carless & Young, 2024; He et al., 2023; Hwang, 2025; Yang & Zhang, 2023).

However, the effectiveness of feedback in writing development largely relies on how learners perceive, interpret, and emotionally respond to it (Cheah & Li, 2020; Hwang, 2025; Pearson, 2022; Ryan & Henderson, 2018; Van der Kleij, 2019; Winstone et al., 2017; Wisniewski et al., 2020). Learners who view feedback as useful, supportive, and non-threatening are more likely to engage in deeper revisions and more actively utilize SRL strategies (Ekholm et al., 2015; Magno & Amarles, 2011; McGrath et al., 2011; Zhu & Carless, 2018). Conversely, feedback perceived as vague or overly critical can diminish motivation and hinder writing progress (Van der Kleij, 2019; Winstone et al., 2017). Despite its significance, empirical studies examining learners’ perceptions of feedback and its impact on learning remain limited (Brown et al., 2016; He et al., 2023). Effective feedback use also requires learners’ active engagement and willingness to accept it (Winstone et al., 2017), both of which are closely tied to the activation of SRL strategies. Writing feedback perception significantly influences self-regulated writing ability, with its impact often mediated by writing self-efficacy and SRL strategies (Hwang, 2025). Since feedback acceptance is influenced by multiple factors, encompassing trust in the feedback provider, learners’ self-concept, and their beliefs about assessment (Pearson, 2022), for feedback practices to be sustainable and effective, both instructors and learners must approach feedback from social and emotional perspectives and foster feedback literacy—the capacity to interpret, engage with, and meaningfully apply feedback (Carless & Young, 2024).

On the other hand, achievement emotions refer to emotional experiences correlated with academic activities and outcomes. These emotions encompass not only subjective feelings but also psychological, cognitive, expressive, and motivational components (Pekrun, 2006). According to Pekrun’s Control-Value Theory (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun et al., 2017) and Efklides’ metacognitive–affective model of SRL (Efklides, 2011), mindsets are a key antecedent of academic emotion and play a central role in driving SRL processes (Bakadorova et al., 2020; Gogol et al., 2017; Van der Beek et al., 2017). Within this framework, achievement emotions influence cognition, motivation, academic performance, and engagement both directly and indirectly (Pekrun et al., 2002, 2007, 2017). Accordingly, those with a growth mindset tend to perceive academic success as controllable and consequently report greater enjoyment in learning. Contrarily, learners with a fixed mindset often feel less control in challenging situations, resulting in increased anxiety and boredom (Burnette et al., 2013; King et al., 2012; Lou & Noels, 2020). Emotions—particularly enjoyment and boredom—significantly impact learning processes and academic achievement (Camacho-Morles et al., 2021; Karlen et al., 2021). Emotion regulation not only addresses emotional responses themselves but also involves the regulation of environmental and evaluative factors that influence emotional experiences (Pekrun & Stephens, 2009). Its core functions include mitigating negative emotions and enhancing positive ones (Thompson, 1994). Academic emotion regulation, defined as the ability to monitor and manage emotions such as anxiety, frustration, and boredom in academic settings, is vital for sustaining motivation, cognitive engagement, persistence, and academic performance (Harley et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2024; Mastrokoukou et al., 2024; Pekrun, 2006; Tzohar-Rozen & Kramarski, 2014). It is also a key contributor to self-regulated writing (Li et al., 2023; L. S. Teng & Zhang, 2016; Yildirim & Atay, 2024). As such, emotion regulation is recognized as a complex, context-sensitive process (Campos et al., 2004). Higher levels of perceived control and task value are associated with increased positive achievement emotions (e.g., enjoyment and hope) and decreased negative emotions (e.g., anxiety and frustration). This framework is especially relevant to writing, a cognitively demanding and emotionally intense task. In writing contexts, emotional experiences—particularly in feedback situations—play a critical role in shaping writing performance (Rowe et al., 2014). Moreover, the emotion regulation strategies employed by language learners influence their achievement emotions (Yildirim & Atay, 2024). Higher levels of emotion regulation are correlated with greater use of cognitive and metacognitive writing strategies, which, in turn, enhance writing performance and boost confidence (L. S. Teng & Zhang, 2016). Notably, boredom has been identified as the most detrimental emotion to writing achievement, while enjoyment positively affects performance (Li et al., 2023), highlighting the significance of effectively managing negative emotions to achieve writing success.

Taken together, the ability to regulate negative emotions is crucial for mitigating writing anxiety, fostering the use of SRL approaches, and sustaining engagement in cognitively demanding tasks such as foreign language or argumentative writing. Ultimately, this contributes to the development of the self-regulated writing ability.

2.3. Relations Among Mindsets, Writing Feedback Perception, Academic Emotion Regulation, and Self-Regulated Writing Ability

Self-regulated writing ability refers to the capacity to strategically complete writing tasks through planning, goal setting, motivation, and emotion regulation throughout the writing process. This ability encompasses more than just cognitive skills; it involves a complex integration of cognitive, motivational, and emotional components, encompassing mindsets, motivational beliefs, feedback perception, emotional regulation, SRL, and SRL strategies (Hwang, 2025; Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994). Recent studies increasingly highlight the need for a comprehensive understanding of how these factors interact to impact the development of self-regulated writing (Hwang, 2025; Karlen et al., 2021; L. S. Teng & Zhang, 2020).

A growth mindset enables learners to interpret challenges and failures as opportunities for improvement and supports both feedback acceptance and emotional regulation (Dweck, 2006; Paunesku et al., 2015). Learners with a growth mindset are more likely to view critical feedback constructively and manage negative emotions effectively, whereas those with a fixed mindset tend to interpret failure as evidence of low ability, which can lead to adverse academic outcomes (Dweck, 2006). Mindsets also influence how learners perceive feedback. Learners with a growth mindset tend to perceive feedback as an opportunity for growth, whereas those with a fixed mindset are more likely to view it as a threat to self-esteem (Dweck, 2006; Hattie & Timperley, 2007). In fact, a growth mindset has been found to significantly impact self-regulated writing approaches through feedback receptivity, whereas a fixed mindset does not display a significant indirect effect (Waller & Papi, 2017).

Moreover, writing feedback perception mediates the interplay between a growth mindset and emotional regulation. When feedback is perceived as clear and actionable, it mitigates negative emotions such as anxiety and frustration while enhancing writing self-efficacy and motivation (Carless & Boud, 2018; Lipnevich et al., 2021). This, in turn, facilitates the utilization of emotion regulation strategies that support planning, goal setting, self-monitoring, and revision, thereby promoting the employment of SRL approaches (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Panadero et al., 2017; Ryan & Henderson, 2018; Winstone et al., 2017). Learners who perceive feedback as useful and actionable tend to develop strong writing self-efficacy, which contributes to strategic planning, self-monitoring, and sustained effort (Ryan & Henderson, 2018; Winstone et al., 2017). Hence, writing feedback perception, writing self-efficacy, and SRL (strategies) are closely interrelated and collectively predict writing performance (Bruning & Kauffman, 2016; Hwang, 2025; Sun & Wang, 2020; L. S. Teng, 2024; Winstone et al., 2017; Zumbrunn et al., 2016). Considering that feedback perception significantly impacts self-regulated writing ability through writing self-efficacy, motivational regulation, and learning strategies, writing instruction should address cognitive, emotional, and psychological dimensions simultaneously (Hwang, 2025; L. S. Teng, 2024). A positive perception of writing feedback also optimizes learners’ emotional regulation. Learners who interpret feedback from a growth-oriented perspective tend to experience fewer negative emotions and develop more effective emotion regulation skills, which strengthens their self-regulated writing ability (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun & Perry, 2014).

A growth mindset encourages learners to embrace challenges and perceive failure as an opportunity for improvement. This orientation is closely correlated with the use of positive emotion regulation strategies, such as cognitive reappraisal (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). Applied to writing, this perspective suggests that a growth mindset may affect self-regulated writing ability through the mediating role of emotional regulation. According to emotion regulation theories, successful learners possess effective coping strategies for managing failure—strategies that often result from the interaction between growth-oriented mindsets and emotion regulation strategies (Gross, 2002). Emotion regulation strategies are crucial for enhancing learners’ writing self-efficacy and motivation and play a critical role even in complex tasks such as writing.

Overall, learners who possess a well-developed growth mindset, a positive perception of writing feedback, and effective academic emotion regulation are better equipped to engage in self-regulated writing (Efklides, 2011; Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994). Although the existing literature underscores the significance of these cognitive, motivational, and emotional factors, few studies have systematically investigated how they collectively predict self-regulated writing ability. Thus, this study aims to address this gap by investigating the integrated effects of mindset, writing feedback perception, and academic emotion regulation on university students’ self-regulated writing ability.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Sampling Procedures

This study investigated the relationships among a growth mindset, writing feedback perception, academic emotion regulation, and self-regulated writing ability. Participants were 313 first-year undergraduate students enrolled in the mandatory “Logical Thinking and Writing” course at H University during the second semester of the 2024 academic year. The course included students from various majors, thus ensuring disciplinary diversity. Before survey administration, the instructor (also the researcher) explained the purpose of the study, emphasizing its use for course improvement and academic research. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all students. The study received ethical approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 7002340-202505-HR-011, approval date: 13 May 2025), and all procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and the university’s IRB guidelines.

Data were collected through a pre-course online survey administered via a secure platform between September 15 and 30, 2024. The survey included demographic items (e.g., gender and major) and measures of the study’s main variables. To ensure data quality, time limits and the required items were implemented. Students were eligible for inclusion if they (1) were enrolled in the course, (2) completed the full survey, and (3) provided informed consent. Students with incomplete responses or unofficial course registration were excluded. The final dataset comprised 313 valid cases. The survey was completed in regular class hours and took approximately 20 min. The average age of the participants was 20.84 years (SD = 1.77). Then, 168 students (53.7%) identified as male and 145 (46.3%) as female; no participants selected the “prefer not to disclose/other” option. In terms of academic background, 33.24% (n = 104) students were enrolled in engineering-related majors—including mechanical information (7.67%), software convergence (8.63%), game software (7.99%), and electronics and electrical convergence engineering (8.95%). The majority (56.87%, n = 178) majored in arts-related disciplines such as design convergence (20.45%), media and animation (15.65%), and game graphics (20.77%). Additionally, 9.9% (n = 31) of the students were pursuing interdisciplinary studies through free major programs at the campus.

3.2. Measures

In this work, a self-reported online survey was administered, and each item was measured using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree.” The survey comprised four sections: mindsets, writing feedback perception, academic emotion regulation, and self-regulated writing ability.

Firstly, mindsets were measured using the Mindset Scale developed by (Dweck, 2006) and translated into Korean by (Choi, 2022). This scale includes two subdomains: growth mindset and fixed mindset, each consisting of four items, for a total of eight items (e.g., “No matter who you are, you can always change your abilities significantly” for the growth mindset; “Your abilities are something very basic about you that you can’t change” for the fixed mindset). A growth mindset refers to the belief that intelligence and abilities can improve through learning and effort, whereas a fixed mindset reflects the belief that intelligence and abilities are unchangeable despite effort. The reliability (Cronbach’s α) of the original scale was 0.775 for the growth mindset and 0.815 for the fixed mindset (Choi, 2022). In this research, the reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s α) were 0.74 for the growth mindset and 0.78 for the fixed mindset. All items for this scale are available in Appendix A.

Secondly, writing feedback perception was assessed using five items selected from (Ekholm et al., 2015) and (Zumbrunn et al., 2016), which were adapted to align with the course objectives. The scale comprised three subfactors—perceptions of instructor feedback, peer feedback, and feedback from acquaintances—with a total of five items (e.g., “I like it when teachers comment on my writing”). The original scale’s reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s α) were 0.81 (Ekholm et al., 2015) and 0.83 (Zumbrunn et al., 2016). In the current research, the scale demonstrated good reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.73. All items for this scale are available in Appendix A.

Thirdly, academic emotion regulation was measured using a scale developed and validated by (J. Yu, 2012), based on the theoretical framework of (Pekrun & Stephens, 2009). This scale includes four subdimensions—emotional awareness, goal-congruent behavior, positive reappraisal of emotions, and access to emotion regulation strategies—each consisting of 6 items, for a total of 24 items (e.g., “Even if I feel frustrated after a test, I quickly forget it and focus on preparing for the next one”). The original scale’s reliability coefficients were 0.81, 0.85, 0.84, and 0.88, respectively (J. Yu, 2012). In this research, the overall reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α) for academic emotion regulation strategies was 0.881, with subdimension coefficients of 0.820 (emotional awareness), 0.823 (goal-congruent behavior), 0.763 (positive reappraisal), and 0.886 (access to strategies). All items for this scale are available in Appendix A.

Fourthly, self-regulated writing ability was assessed using 12 items (e.g., “Before I write, I set goals for my writing”) from (Zumbrunn et al., 2016), covering seven subdimensions: goal setting, planning, self-monitoring, attention control, emotion regulation, self-instruction, and help-seeking in writing. The original scale reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.79 (Zumbrunn et al., 2016), whereas this study obtained a reliability coefficient of 0.777. All items for this scale are available in Appendix A.

The internal consistency reliability of each construct was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. All subscales demonstrated sufficient unidimensionality; thus, this method was considered appropriate. Although McDonald’s omega may provide certain advantages, Cronbach’s alpha remains a valid and widely accepted estimate of reliability, particularly in unidimensional scales, such as those used in this study.

3.3. A Priori Power Analysis and Sample Size Justification

A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1. Assuming a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15, which is equivalent to Cohen’s f = 0.387), significance level of α = 0.05, and a desired power of 0.80, the minimum required sample size for the detection of an overall effect in a multiple regression model with five predictors was calculated to be approximately 91. The final sample of 313 exceeded this threshold, ensuring sufficient statistical power not only for multiple regression but also for the serial mediation analysis conducted using PROCESS Model 6, which involved two mediators arranged in a pre-specified causal sequence.

3.4. Data Analysis

To answer RQ1, correlation analysis and hierarchical multiple regression analysis were conducted to explore the relationships among key variables. To address RQs 2–4, SPSS Statistics 29 and the PROCESS macro (Model 6) were employed to test the hypothesized serial mediation model. Firstly, prior to analysis, missing values were identified and replaced using the Expectation–Maximization (EM) method to ensure data quality. Secondly, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to assess the internal consistency reliability of the measurement instruments. Thirdly, descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis, were examined to evaluate data distribution and response patterns. Pearson correlation coefficients were then computed to assess linear relationships among continuous variables, as assumptions of normality were met. Finally, data were analyzed using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 6; Hayes, 2017), which is specifically designed for serial mediation analysis. This model was selected because it enables the examination of multiple mediators in a predetermined causal sequence, thus fitting the theoretical assumptions of this study. In particular, it allows for testing both simple and sequential indirect effects, reflecting how mindsets may influence writing outcomes in intermediate cognitive and emotional mechanisms. Regression-based mediation analysis was conducted using 5000 bootstrap samples, and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals were used to assess the significance of indirect effects. This analytical framework enabled the evaluation of both direct and indirect effects, including simple and sequential dual mediation, thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of how learners’ beliefs, feedback perception, and emotion regulation together contribute to their self-regulated writing ability.

4. Results

4.1. Scale Validation

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate the construct validity of the four-factor measurement model, which included growth mindset, feedback perception, academic emotion regulation, and self-regulated writing ability. Table 1 exhibits the goodness-of-fit indices for the four-factor measurement model, indicating a good fit to the data: χ2(205) = 205.00, p = 0.487, χ2/df = 1.85, RMSEA = 0.045, SRMR = 0.035, CFI = 0.962, and TLI = 0.958. The subscales—mindsets, writing feedback perception, academic emotion regulation, and self-regulated writing ability—also exhibited adequate convergent validity, with average variance extracted (AVE) values of 0.58, 0.61, 0.55, and 0.59, respectively. Additionally, multicollinearity was not detected, as indicated by the variance inflation factor (VIF) values ranging from 1.33 to 1.55.

Table 1.

Findings of the goodness of fit of the scale model.

All observed variables were loaded significantly into their respective latent constructs. The standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.683 to 0.821, and the R2 values ranged from 0.467 to 0.674, showing that each item accounted for a substantial proportion of the variance in its corresponding latent factor. These findings support the factorial validity of the five-factor measurement model, showing satisfactory levels of indicator reliability and convergent validity. Table 2 presents the standardized factor loadings and squared multiple correlations (R2) for each latent construct.

Table 2.

Standardized factor loadings and R2 for the five-factor CFA model.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis Between Variables

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlation coefficients for the key variables. The following abbreviations are used throughout the results and tables: growth mindset (GM), fixed mindset (FM), feedback perception (FBP), academic emotion regulation (AER), and self-regulated writing (SRW).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis results.

Because all variables satisfied the assumption of normality, as indicated by skewness values ranging from 0.015 to 0.535 and kurtosis values ranging from 0.036 to 1.273, Pearson’s r was deemed appropriate for the examination of the linear relationships among continuous variables. A GM was positively correlated with SRW ability (r = 0.453) and AER (total) (r = 0.326), whereas an FM showed negative correlations with both SRW ability (r = −0.233) and AER (total) (r = −0.057). In addition, AER (total) and SRW ability were positively correlated (r = 0.478). These correlation results confirm H1, demonstrating that a growth mindset is positively associated with feedback perception, academic emotion regulation, and self-regulated writing ability.

4.3. Verification of the Predictive Power of Mindsets, Writing Feedback Perception, and Academic Emotion Regulation on Self-Regulated Writing Ability

To examine the effects of mindsets, writing feedback perception, and AER on SRW ability, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted. Multicollinearity was tested to ensure the independence of the variables. Tolerance values ranged from 0.71 to 0.76, which is within the acceptable range (0–1), and all VIF values were all below 10, indicating no multicollinearity issues. The detailed results showing how first-year university students’ perceptions of mindset, writing feedback, and AER influence SRW ability are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Effect of mindsets (GM, FM), FBP, and AER on SRW.

Model 1 examined the effect of the GM on SRW ability. The results confirmed that the GM accounted for 17.3% of the variance (F = 43.254, p < 0.001). A higher perception of the GM was correlated with higher SRW ability (ß = 0.416, p < 0.001). In Model 2, the FM was added while controlling for the GM. The explanatory power remained at 17.3%, and the FM did not significantly contribute to the model (β = −0.006, p = 0.930). While the FM was not a significant predictor for Model 2, it was retained in Models 3 and 4 to maintain the theoretical consistency and control for potential suppressor effects. This approach ensures that the subsequent predictive contributions of writing feedback perception and AER are evaluated while accounting for variance that can be potentially explained by an FM. The hierarchical inclusion of variables was guided with theoretical rationale: mindset variables were entered first, as they represented foundational learner beliefs, which was followed by writing feedback perception and AER, which are conceptually and proximally linked to SRW behavior. In Model 3, writing feedback perception was added while controlling for the growth and fixed mindsets. The explanatory power increased to 25.1% (F = 21.533, p < 0.001). Writing feedback perception had a significantly positive effect on SRW ability (ß = 0.311, p < 0.001), highlighting that learners with a more positive perception of writing feedback exhibit higher SRW ability. In Model 4, AER was added while controlling for the GM, FM, and writing feedback perception. The model’s explanatory power significantly increased to 35.4% (F = 32.202, p < 0.001). AER was the strongest predictor of SRW ability (ß = 0.344, p < 0.001), suggesting that a learner’s ability to regulate emotions plays a crucial role in fostering effective SRW.

4.4. Inferential Statistics

In this research, the fixed mindset—initially included in the research model—was found to have no significant effect on writing feedback perception, AER, or SRW ability. Accordingly, the final model excluded the FM and analyzed only the pathways centered on the GM. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that a GM, rather than an FM, is more closely associated with psychological and behavioral factors related to learners’ self-regulation (Dweck, 2006).

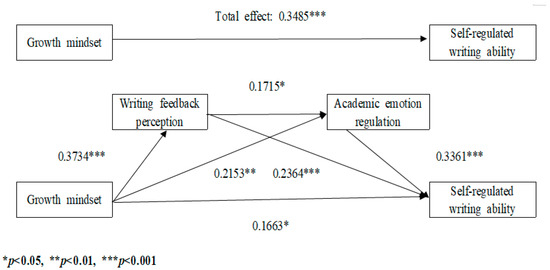

To verify the mediation effects of writing feedback perception and AER in the interplay between the GM and SRW ability, the PROCESS macro Model 6 proposed by Hayes (2017) was applied. In the analysis, GM was designated as the independent variable (X), SRW ability as the dependent variable (Y), and writing feedback perception (M1) and AER (M2) as the mediators. The results of the mediation analysis, encompassing all direct and indirect paths, are presented in Table 5 and visually illustrated in Figure 2 as a conceptual path model.

Table 5.

Effect size for each path.

Figure 2.

Multiple serial mediation effects of FBP and AER on the interplay between GM and SRW.

The path analysis revealed that all specified relationships were statistically significant, supporting the hypothesized mediation model. Firstly, a GM positively predicted writing feedback perception (B = 0.3734, p < 0.001), AER (B = 0.2153, p < 0.01), and SRW ability (B = 0.1663, p < 0.05). Secondly, writing feedback perception positively predicted AER (B = 0.1715, p < 0.05) and SRW ability (B = 0.2364, p < 0.001). Thirdly, AER was identified as the strongest predictor of SRW ability, exhibiting a significantly positive effect (B = 0.3361, p < 0.001).

According to Hayes (2017), a mediation effect is established when the following conditions are met: the interplay between the independent variable (IV) and the dependent variable (DV) is significant. The interplay between the IV and the mediator is significant. When the mediator is added, the total effect of the IV on the DV increases. In this study model, the direct effect of a GM on SRW ability (B = 0.1663, p < 0.05) was lower than the total effect when the mediators were included (B = 0.3485, p < 0.001). This indicates that writing feedback perception and AER serve as mediators in the interplay between a GM and SRW ability.

A more detailed analysis confirmed that the indirect effect through writing feedback perception, the indirect effect through AER, and the sequential indirect effect through both writing feedback perception and AER were all statistically significant. To test the serial dual mediation model, 5000 bootstrapped samples were generated with a 95% confidence interval. The unstandardized indirect effects are reported in Table 6, and the completely standardized indirect effects are presented in Table 7. The indirect effects through both writing feedback perception and AER were statistically significant, supporting H2 and H3, respectively.

Table 6.

Unstandardized indirect effects and 95% bootstrap confidence intervals.

Table 7.

Completely standardized indirect effects and 95% bootstrap confidence intervals.

The specific indirect effect of a GM on SRW ability through writing feedback perception (X → M1 → Y) was 0.0883 (unstandardized B, 95% CI [0.0414, 0.1489]) and 0.1053 (standardized B, 95% CI [0.0507, 0.1696]), both indicating a statistically significant mediation effect. Additionally, the indirect effect through AER (X → M2 → Y) was 0.0724 (unstandardized B, 95% CI [0.0256, 0.1316]) and 0.0863 (standardized B, 95% CI [0.0308, 0.1523]), which were also significant. The serial dual mediation effect through both mediators (X → M1 → M2 → Y) was 0.0215 (unstandardized B, 95% CI [0.0044, 0.0435]) and 0.0257 (standardized B, 95% CI [0.0053, 0.0516]). As such, none of the confidence intervals included zero; thus, all indirect paths were statistically significant. Finally, the total indirect effect of a GM on SRW ability was 0.1822 (unstandardized B, 95% CI [0.1069, 0.2686]) and 0.2173 (standardized B, 95% CI [0.1343, 0.3099]), confirming a robust overall mediation effect. These findings validate H4, as the serial indirect effect through both feedback perception and AER was statistically significant.

In summary, both the unstandardized and standardized analyses confirmed that writing feedback perception and AER significantly mediated the effect of a GM on SRW ability, with all individual and combined indirect paths reaching statistical significance. Figure 2 illustrates the structural equation model, including the total, direct, and indirect paths from a GM to SRW ability, mediated by writing feedback perception and AER. The coefficients presented reflect unstandardized direct effects, where all paths reach statistical significance, thereby supporting the proposed serial mediation mechanism.

5. Discussion

This research investigated how a GM, writing feedback perception, and AER individually and collectively affect SRW ability. The main findings are as follows: Firstly, a GM had a significantly positive effect on SRW ability, whereas an FM was not a significant predictor. This finding supports previous research showing that a GM enhances sustained effort, persistence, and SRL behaviors, and is more strongly associated with emotional regulation than an FM (Bai & Wang, 2023; Burnette et al., 2013; Dweck, 2006; Karlen et al., 2021; M. F. Teng et al., 2024; Yeager & Dweck, 2020). In writing contexts, a GM promotes goal setting, self-monitoring, and strategic use, even in complex tasks, and fosters perseverance and openness to challenges (Dweck & Leggett, 1988; M. F. Teng et al., 2024). In addition, writing feedback perception significantly predicted SRW ability, even after controlling for mindset. This finding aligns with studies that have shown that learners who perceive feedback as constructive are more likely to engage in self-regulated revision and strategic learning (He et al., 2023; Panadero et al., 2017; Winstone et al., 2017; Zhu & Carless, 2018). Effective feedback supports performance monitoring and strategic adjustment and is linked to increased self-efficacy, motivation, and academic success (Ekholm et al., 2015; Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). Finally, AER was the strongest predictor of SRW ability. It helps alleviate negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, frustration, and boredom), supports persistence and higher-order strategy use, and enhances perceived control and task value (Camacho-Morles et al., 2021; Efklides, 2011; Harley et al., 2019; Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun et al., 2017). Learners with better emotion regulation maintain their self-efficacy and motivation, contributing to more active SRL (L. S. Teng & Zhang, 2016).

These findings identified a GM, positive writing feedback perception, and AER as key contributors to SRW ability. These factors interact to enhance learners’ writing performance and self-regulation. The findings highlight the importance of fostering a GM, promoting constructive feedback perception, and supporting emotion regulation in college writing education. Accordingly, educational programs should aim to strengthen a GM (Yeager & Dweck, 2020), feedback literacy (Carless & Young, 2024), and emotion regulation strategies (Pekrun et al., 2007; Tzohar-Rozen & Kramarski, 2014) to support learners’ SRW.

Secondly, the mediating role of writing feedback perception on the relationship between a GM and SRW ability was confirmed. Learners with a GM tended to perceive feedback as positive and useful, which encouraged the use of SRW strategies and enhanced writing ability (Waller & Papi, 2017). This aligns with prior research, which showed that learners who view feedback as an opportunity for improvement are more likely to engage in self-monitoring and strategic revision (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Panadero et al., 2017; Zhu & Carless, 2018). Feedback perception also supports writing improvement by boosting self-efficacy and motivation (Ekholm et al., 2015; Zumbrunn et al., 2016), and plays a central role in promoting feedback engagement and SRL (Hwang, 2025; Winstone et al., 2017; Zhu & Carless, 2018). These findings underscore the importance of developing students’ feedback literacy—the ability to interpret, evaluate, and apply feedback effectively (Carless & Boud, 2018; Carless & Young, 2024). Feedback literacy involves critical reflection and emotional regulation in response to feedback (Pearson, 2022; Zhu & Carless, 2018). The present study empirically supports the structural linkage between a GM, feedback perception, and SRW, highlighting the need for pedagogical practices that enhance feedback interpretation, encourage dialogic feedback, and integrate strategy-based writing instruction (Carless & Young, 2024; Winstone et al., 2017).

Thirdly, the mediating effect of AER in the interplay between a GM and SRW ability was also found to be significant. This finding supports previous research indicating that emotion regulation has a substantial impact on learning motivation, strategy use, and task persistence (Pekrun, 2006). In academic contexts, emotion regulation facilitates the usage of higher-order approaches and sustained engagement (Camacho-Morles et al., 2021; Harley et al., 2019; Karlen et al., 2021) by alleviating negative emotions and enhancing positive ones (Efklides, 2011; Tzohar-Rozen & Kramarski, 2014). Emotion regulation is particularly critical in writing, which is inherently cognitively and emotionally demanding (Harley et al., 2019; Rowe et al., 2014). Learners with stronger AER experience less writing anxiety, exhibit greater persistence, and engage more in strategic revisions (Li et al., 2023; L. S. Teng & Zhang, 2016). In this context, emotion regulation serves to mitigate emotions such as frustration and boredom while supporting self-efficacy and sustained task engagement (Harley et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023; Yildirim & Atay, 2024). Thus, integrating emotion regulation training into writing instruction is essential. Strategies such as emotion awareness, cognitive reappraisal, and goal maintenance (Pekrun et al., 2017) can be effectively embedded in writing courses and integrated with metacognitive approaches to further optimize learners’ SRW (Efklides, 2011; Gross & John, 2003; Pekrun & Perry, 2014).

Finally, a sequential double mediation model revealed that writing feedback perception and AER significantly mediated the interplay between a GM and SRW ability. This provides empirical support for the process by which learners who view feedback positively and regulate their emotional responses tend to engage in strategic and autonomous writing behaviors (Lipnevich et al., 2021; Panadero et al., 2017). This finding aligns with theoretical perspectives that conceptualize SRL as an integrated process encompassing cognitive, motivational, and emotional regulation (Pekrun, 2006; Zimmerman, 2000). Specifically, a GM encourages learners to interpret feedback as opportunities for development (Dweck, 2006), which fosters positive feedback perception (Winstone et al., 2017). In turn, this perception activates emotion regulation approaches that optimize self-regulatory capacity in writing (Carless & Young, 2024; Hwang, 2025). These findings highlight that learners’ responses to feedback are not merely cognitive but involve complex emotional interpretations that are reconstructed into practical learning behaviors (Pearson, 2022; Ryan & Henderson, 2018; Zhu & Carless, 2018).

Educational implications point to the need for instructional interventions that go beyond the mere provision of feedback to foster learners’ interpretation, emotional regulation, and internalization of feedback into self-regulated behaviors (Ajjawi et al., 2022; Winstone et al., 2017). To this end, cognitive and emotional scaffolding should be utilized (Nash & Winstone, 2017). For instance, writing instructions may incorporate activities such as exploring emotional responses after receiving feedback, feedback interpretation workshops, and dialogic feedback sessions utilizing emotion regulation approaches such as reappraisal and attentional shift. These practices can help learners reframe feedback as a resource for personal growth and support sustained SRW in emotionally secure learning environments.

These findings may appear generalizable but should be properly interpreted in light of the Korean cultural context of the sample. Cultural norms concerning authority, emotional expression, and academic feedback are likely influential on how the learners in this study perceived and responded to feedback. In East Asian educational settings, students often display heightened sensitivity to instructor evaluations and tend to internalize feedback emotionally. These cultural dimensions should be considered when applying the findings to different populations and educational systems. The study provides evidence for a dynamic and interrelated model of writing development that integrates cognitive, emotional, and motivational processes. A GM enhances FBP, which in turn fosters emotion regulation, ultimately supporting SRW. These findings indicate the need for a shift in writing instruction from a purely strategy-based approach toward a holistic pedagogical design embracing cognitive, emotional, and cultural dimensions in support of learners’ SRW.

6. Limitations and Future Directions of This Study

Despite the insights offered by this study, future research should address several limitations. Firstly, the data were collected through self-reported questionnaires, which are inherently subject to biases such as social desirability and recall inaccuracies. Consequently, the findings should be interpreted with caution, particularly with respect to the accuracy of the participants’ cognitive and emotional processes in writing. Future research should consider incorporating behavioral measures or observational methods to capture more authentic writing-related behaviors.

Secondly, the cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to draw definitive causal inferences among the variables. Constructs such as mindset, feedback perception, and AER are dynamic and may evolve or exert reciprocal influences over time. Longitudinal or experimental research designs are required to validate the directionality and stability of the observed relationships.

Thirdly, the sample consisted of first-year university students from a single institution in South Korea, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other populations or educational contexts. Cultural factors and institutional practices can significantly influence learners’ beliefs, emotional responses, and feedback orientations. The sample was obtained via convenience sampling; however, its disciplinary diversity partially mitigates concerns regarding generalizability. To enhance their representativeness, future studies should adopt stratified sampling methods that systematically account for variations in academic performance, major, and language background.

Fourthly, while this study focused on a GM, writing feedback perception, and AER, other important factors—such as writing self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation, metacognitive strategies, and external support systems—were not included in the analysis. Expanding the model to include these variables could offer a more comprehensive account of the mechanisms that contribute to SRW ability.

Fifthly, although the instruments used were validated in previous studies, they may not fully capture the nuanced and context-dependent nature of constructs like AER and feedback perception. Future research could benefit from using real-time or context-sensitive assessment tools, such as learning analytics or AI-based tracking systems, to gain more granular insights into learners’ behaviors.

Finally, this study relied solely on quantitative methods. While statistical analysis helped clarify variable relationships, it did not explore the qualitative dimensions of learners’ writing experiences, such as how they interpret feedback or manage emotional challenges during actual writing tasks. Future research should consider mixed-methods approaches, including interviews, reflective journals, or think-aloud protocols, to provide richer, more contextualized understandings of SRW processes.

7. Conclusions

The current research investigated the effects of a GM, writing feedback perception, and AER on SRW ability among university students, analyzing both direct and indirect relationships. Unlike previous studies that explored these variables in isolation, this work empirically investigated their interactions and structural relationships, thereby offering a multi-layered understanding of the formation of SRW ability. Firstly, the findings underscore the integrated role of psychological and emotional factors as key determinants of SRW ability. This emphasizes the importance of moving beyond strategy-based writing instruction to address learners’ internal mindsets, emotional responses, and feedback interpretation skills as essential components of SRW performance. Secondly, the results verified that a GM not only directly influences SRW ability but also exerts an indirect effect through writing feedback perception and AER. Specifically, the sequential mechanism between feedback perception and AER demonstrates that feedback functions not merely as an external stimulus but as a cognitive–emotional catalyst that fosters self-regulation. Thirdly, this work redefines SRW ability as a learner-centered competence integrating cognition, motivation, and emotion, rather than a mere set of strategic skills. This perspective proposes that writing instruction should move beyond skill training to a more comprehensive pedagogical design encompassing learners’ cognitive processes, emotional engagement, and self-belief. Fourthly, from an educational standpoint, the study recommends an integrated instructional framework in university writing courses that encompasses fostering a GM, refining feedback literacy, and developing emotional regulation strategies. Such a holistic approach underscores the need for long-term, systemic approaches to enhance learners’ self-directed writing abilities. Finally, by presenting an integrative model of SRW ability, this research offers a theoretical and practical foundation for future longitudinal and context-specific studies. Notably, the emphasis on the mediating role of AER contributes to scholarly attention to the emotional aspects of writing education, which have been relatively underexplored. Overall, this work offers empirical evidence that enhancing SRW ability necessitates instructional designs that simultaneously enhance learners’ growth-oriented mindset, feedback interpretation skills, and emotional regulation capacity. These results provide valuable insights for reimagining the future of university-level writing education.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study received ethical approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 7002340-202505-HR-011, approval date: 13 May 2025), and all procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and the university’s IRB guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Scale Items

Appendix A.1. Mindset

Growth Mindset Items

- No matter who you are, you can always change your abilities significantly.

- You can always develop your abilities through effort and learning.

- With enough effort, anyone can improve their performance in most areas.

- Even your most basic qualities can be improved substantially over time.

Fixed Mindset Items

- Your abilities are something very basic about you that you can’t change much.

- No matter how much intelligence you have, you can’t really change it very much.

- You have a certain amount of ability, and you really can’t do much to change it.

- Trying hard doesn’t make a big difference because ability is mostly fixed.

Appendix A.2. Writing Feedback Perception Scale

- I like talking with my teachers about my writing.

- I like it when teachers comment on my writing.

- I feel good about teachers’ comments about my writing.

- I feel good about my classmates’ comments about my writing.

- I feel good about my family members’ comments about my writing.

Appendix A.3. Academic Emotion Regulation Scale

- When I feel bored while studying, I know why I feel that way.

- When I feel frustrated after a test, I understand why I feel that way.

- When I feel helpless while studying, I know the reason behind that feeling.

- When I feel anxious while studying, I understand why I feel that way.

- When I get angry while studying, I can identify the reason for my emotion.

- When I feel anxious during a test, I know why I feel that way.

- Even if I feel frustrated after a test, I quickly forget it and focus on studying for the next one.

- Even if I feel helpless while studying, I can still complete my work.

- Even if I feel anxious during a test, I can stay focused on the test.

- Even if I feel anxious while studying, I can stay focused on my studies.

- Even if I feel ashamed of a poor test result, I can concentrate on studying for the next one.

- Even if I get angry while studying, I can stay focused.

- When I feel bored while studying, I imagine myself feeling satisfied after finishing the task.

- When I feel helpless while studying, I recall a time when I studied hard and succeeded.

- Even if I feel frustrated after a test, I consider it a necessary step for my personal growth.

- When I get angry while studying, I think of a time when I studied hard.

- When I feel anxious while studying, I visualize a successful future version of myself.

- When I feel anxious during a test, I picture myself feeling satisfied after completing it.

- Even if I feel bored while studying, I know how to re-energize myself.

- When I get angry while studying, I know how to calm myself down.

- Even if I feel anxious during a test, I know how to soothe myself.

- When I feel ashamed after a test, I know how to calm myself down.

- Even if I feel anxious while studying, I know ways to feel at ease.

- Even if I feel helpless while studying, I know how to regain focus.

Appendix A.4. Self-Regulated Writing Ability Scale

- Before I start writing, I plan what I want to write.

- Before I write, I set goals for my writing.

- I think about who will read my writing.

- I think about how much time I have to write.

- I ask for help if I have trouble writing.

- While I write, I think about my writing goals.

- I keep writing even when it’s difficult.

- While I write, I avoid distractions.

- When I get frustrated with my writing, I make myself relax.

- While I write, I talk myself through what I need to do.

- I make my writing better by changing parts of it.

- I tell myself I did a good job when I write my best.

References

- Ajjawi, R., Kent, F., Broadbent, J., Tai, J. H. M., Bearman, M., & Boud, D. (2022). Feedback that works: A realist review of feedback interventions for written tasks. Studies in Higher Education, 47(7), 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B., & Wang, J. (2023). The role of growth mindset, self-efficacy and intrinsic value in self-regulated learning and English language learning achievements. Language Teaching Research, 27(1), 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakadorova, O., Lazarides, R., & Raufelder, D. (2020). Effects of social and individual school self-concepts on school engagement during adolescence. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 35(1), 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, M., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2003). Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educational Psychology Review, 15, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. T., Peterson, E. R., & Yao, E. S. (2016). Student conceptions of feedback: Impact on self-regulation, self-efficacy, and academic achievement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(4), 606–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruning, R., & Kauffman, D. F. (2016). Self-efficacy beliefs and motivation in writing development. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (2nd ed., pp. 160–173). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burnette, J. L., O’boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2013). Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 655–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Morles, J., Slemp, G. R., Pekrun, R., Loderer, K., Hou, H., & Oades, L. G. (2021). Activity achievement emotions and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 33(3), 1051–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J. J., Frankel, C. B., & Camras, L. (2004). On the nature of emotion regulation. Child Development, 75(2), 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling the uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D., & Young, S. (2024). Feedback seeking and student reflective feedback literacy: A sociocultural discourse analysis. Higher Education, 88(3), 857–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, S., & Li, S. (2020). The effect of structured feedback on performance: The role of attitude and perceived usefulness. Sustainability, 12(5), 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. (2022). Effect of mindset on innovation behavior through job crafting: Focusing on the moderating effect of informal learning [Master’s thesis, Chungang University]. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S. (2017). From needs to goals and representations: Foundations for a unified theory of motivation, personality, and development. Psychological Review, 124(6), 689–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efklides, A. (2011). Interactions of metacognition with motivation and affect in self-regulated learning: The MASRL model. Educational Psychologist, 46(1), 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekholm, E., Zumbrunn, S., & Conklin, S. (2015). The relationship between college student self-efficacy toward writing and writing self-regulation: Writing feedback perceptions as a mediating variable. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(2), 197–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esnaashari, S., Gardner, L. A., Arthanari, T. S., & Rehm, M. (2023). Unfolding self-regulated learning profiles of students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39(4), 1116–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogol, K., Brunner, M., Martin, R., Preckel, F., & Goetz, T. (2017). Affect and motivation within and between school subjects: Development and validation of an integrative structural model of academic self-concept, interest, and anxiety. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in the two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimovitz, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). What predicts children’s fixed and growth intelligence mindsets? Not their parents’ views of intelligence but their parents’ views of failure. Psychological Science, 27(6), 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, J. M., Pekrun, R., Taxer, J. L., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Emotion regulation in achievement situations: An integrated model. Educational Psychologist, 54(2), 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K. R. (2024). The self-regulated strategy development instructional model: Efficacious theoretical integration, scaling up, challenges, and future research. Educational Psychology Review, 36(4), 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of the feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- He, J., Liu, Y., Ran, T., & Zhang, D. (2023). How students’ perception of feedback influences self-regulated learning: The mediating role of self-efficacy and goal orientation. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 38(4), 1551–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, S., Saqr, M., Malmberg, J., & Tedre, M. (2025). A longitudinal study of interplay between student engagement and self-regulation. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 22(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S. (2025). Unpacking the impact of writing feedback perception on self-regulated writing ability: The role of writing self-efficacy and self-regulated learning Strategies. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S., & Choi, L. (2024). Mediating effects of self-regulated learning strategies in the relationship between mindsets and adaptation to college among Chinese international students. Global Studies Education, 16(3), 69–106. Available online: https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART003126859 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Karlen, Y., Hirt, C. N., Liska, A., & Stebner, F. (2021). Mindsets and self-concepts about self-regulated learning: Relationships with emotions, strategy knowledge, and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 661142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlen, Y., Suter, F., Hirt, C., & Merki, K. M. (2019). The role of implicit theories in students’ grit, achievement goals, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and achievement in the context of a long-term challenging task. Learning and Individual Differences, 74, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. B., McInerney, D. M., & Watkins, D. A. (2012). How you think about your intelligence determines how you feel in school: The role of theories of intelligence on academic emotions. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(6), 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Wei, L., & Lu, X. (2023). Contributions of foreign language writing emotions to writing achievement. System, 116, 103074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S., Mastrokoukou, S., Longobardi, C., & Bozzato, P. (2024). The influence of resilience and future orientation on academic achievement during the transition to high school: The mediating role of social support. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 29(1), 2312863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipnevich, A. A., Murano, D., Krannich, M., & Goetz, T. (2021). Should I grade or should I comment: Links among feedback, emotions, and performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 89, 102020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, N. M., & Noels, K. A. (2020). Breaking the vicious cycle of language anxiety: Growth language mindsets improve lower-competence ESL students’ intercultural interactions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magno, C., & Amarles, A. (2011). Teachers’ feedback practices in second language academic writing classrooms. The International Journal of Education and Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 21–30. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2287181 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Mastrokoukou, S., Lin, S., Longobardi, C., Berchiatti, M., & Bozzato, P. (2024). Resilience and psychological distress in the transition to university: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Current Psychology, 43, 23675–23685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, A. L., Taylor, A., & Pychyl, T. A. (2011). Writing helpful feedback: The influence of feedback type on students’ perceptions and writing performance. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 2(2), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molden, D. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2006). Finding “meaning” in psychology: A lay theory approach self-regulation, social per-ception, and social development. American Psychologist, 61(3), 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, R. A., & Winstone, N. E. (2017). Responsibility-sharing in the giving and receiving of assessment feedback. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommundsen, Y., Haugen, R., & Lund, T. (2005). Academic self-concept, implicit theories of ability, and self-regulation strategies. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 49(5), 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E., Jonsson, A., & Botella, J. (2017). Effects of self-assessment on self-regulated learning and self-efficacy: Four meta-analyses. Educational Research Review, 22, 74–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., Romero, C., Smith, E. N., Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Mind-set interventions are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychological Science, 26(6), 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, W. S. (2022). Mediating effects of student beliefs on engagement with written feedback in preparation for high-stakes English writing assessment. Assessing Writing, 52, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educa-tional research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2007). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: An integrative approach to emotions in education. In P. A. Schutz, & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion in education (pp. 13–36). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Lichtenfeld, S., Marsh, H. W., Murayama, K., & Goetz, T. (2017). Achievement emotions and academic performance: Longitudinal models of reciprocal effects. Child Development, 88(5), 1653–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., & Perry, R. P. (2014). Control-value theory of achievement emotions. In International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 120–141). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R., & Stephens, E. J. (2009). Goals, emotions, and emotion regulation: Perspectives of the control-value theory. Human Development, 52(6), 357–365. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26764929 (accessed on 17 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rattan, A., Savani, K., Chugh, D., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Leveraging mindsets to promote academic achievement: Policy recommendations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(6), 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gomez, D., Muñoz-Moreno, J. L., & Ion, G. (2024). Empowering teachers: Self-regulated learning strategies for sustainable professional development in initial teacher education at higher education institutions. Sustainability, 16(7), 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, A. D., Fitness, J., & Wood, L. N. (2014). The role and functionality of emotions in feedback at university: A qualitative study. The Australian Educational Researcher, 41, 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T., & Henderson, M. (2018). Feeling feedback: Students’ emotional responses to the educator’s feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(6), 880–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T., & Wang, C. (2020). College students’ writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulated learning strategies in learning English as a foreign language. System, 90, 102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L. S. (2024). Individual differences in self-regulated learning: Exploring the nexus of motivational beliefs, self-efficacy, and SRL strategies in EFL writing. Language Teaching Research, 28(2), 366–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L. S., & Huang, J. (2019). Predictive effects of writing strategies for self-regulated learning on secondary school learners’ writing proficiency. TESOL Quarterly, 53(1), 232–247. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45214917 (accessed on 20 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Teng, L. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2016). A questionnaire-based validation of multidimensional models of self-regulated learning strategies. The Modern Language Journal, 100(3), 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2020). Empowering learners in the second/foreign language classroom: Can self-regulated learning strategies-based writing instruction make a difference? Journal of Second Language Writing, 48, 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M. F., Mizumoto, A., & Takeuchi, O. (2024). Understanding the growth mindset, self-regulated vocabulary learning, and vocabulary knowledge. System, 122, 103255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2/3), 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzohar-Rozen, M., & Kramarski, B. (2014). Metacognition, motivation and emotions: Contribution of self-regulated learning to solving mathematical problems. Global Education Review, 1(4), 76–95. Available online: https://ger.mercy.edu/index.php/ger/article/view/63 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Van der Beek, J. P., Van der Ven, S. H., Kroesbergen, E. H., & Leseman, P. P. (2017). Self-concept mediates the relation between achievement and emotions in mathematics. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(3), 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Kleij, F. M. (2019). Comparison of teacher and student perceptions of formative assessment feedback practices and their association with individual student characteristics. Teaching and Teacher Education, 85, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, L., & Papi, M. (2017). Motivation and feedback: How implicit theories of intelligence predict L2 writers’ motivation and feedback orientation. Journal of Second Language Writing, 35, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Parker, M., & Rowntree, J. (2017). Supporting learners’ agentic engagement with feedback: A systematic review and a taxonomy of recipience processes. Educational Psychologist, 52(1), 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., & Hattie, J. (2020). The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 487662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y., & Yang, M. (2019). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: How formative assessment supports students’ self-regulation in English language learning. System, 81, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. (2022). Incremental intelligence matters: How L2 writing mindsets impact feedback orientation and self-regulated learning writing strategies. Assessing Writing, 51, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, V. X., Thai, K.-P., & Bjork, R. A. (2014). Habits and beliefs that guide self-regulated learning: Do they vary with mindset? Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3(3), 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. F., & Zhang, L. J. (2023). Self-regulation and student engagement with feedback: The case of Chinese EFL student writers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 63, 101226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2020). What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? American Psychologist, 75(9), 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, A., & Atay, D. (2024). Investigating language learners’ emotion regulation strategies via achievement emotions in language learning contexts. TEFLIN Journal, 35(1), 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. (2012). Test of a structural equation model among academic emotion regulation, learning strategy, academic self-efficacy and academic achievement [Doctorate thesis, Sookmyung Women’s University]. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q., & Schunn, C. D. (2023). Understanding the what and when of peer feedback benefits for performance and transfer. Computers in Human Behavior, 147, 107857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q., & Carless, D. (2018). Dialogue within peer feedback processes: Clarification and negotiation of meaning. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(4), 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Bandura, A. (1994). Impact of self-regulatory influences on writing course attainment. American Educational Research Journal, 31(4), 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumbrunn, S., Marrs, S., & Mewborn, C. (2016). Toward a better understanding of student perceptions of writing feedback: A mixed methods study. Reading and Writing, 29, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).