Digital and Digitized Interventions for Teachers’ Professional Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Work Engagement and Burnout Using the Job Demands–Resources Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

Digital and Digitized Interventions Aimed at Teachers’ Burnout and Work Engagement

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) Theory, Burnout, and Work Engagement

2.2. Implementation Factors in Efficient Interventions

2.3. Core Components Focusing on Job Demands, Personal and Job Resources

2.4. What Is the Optimal Duration and Dosage?

2.5. The Present Study

3. Methods

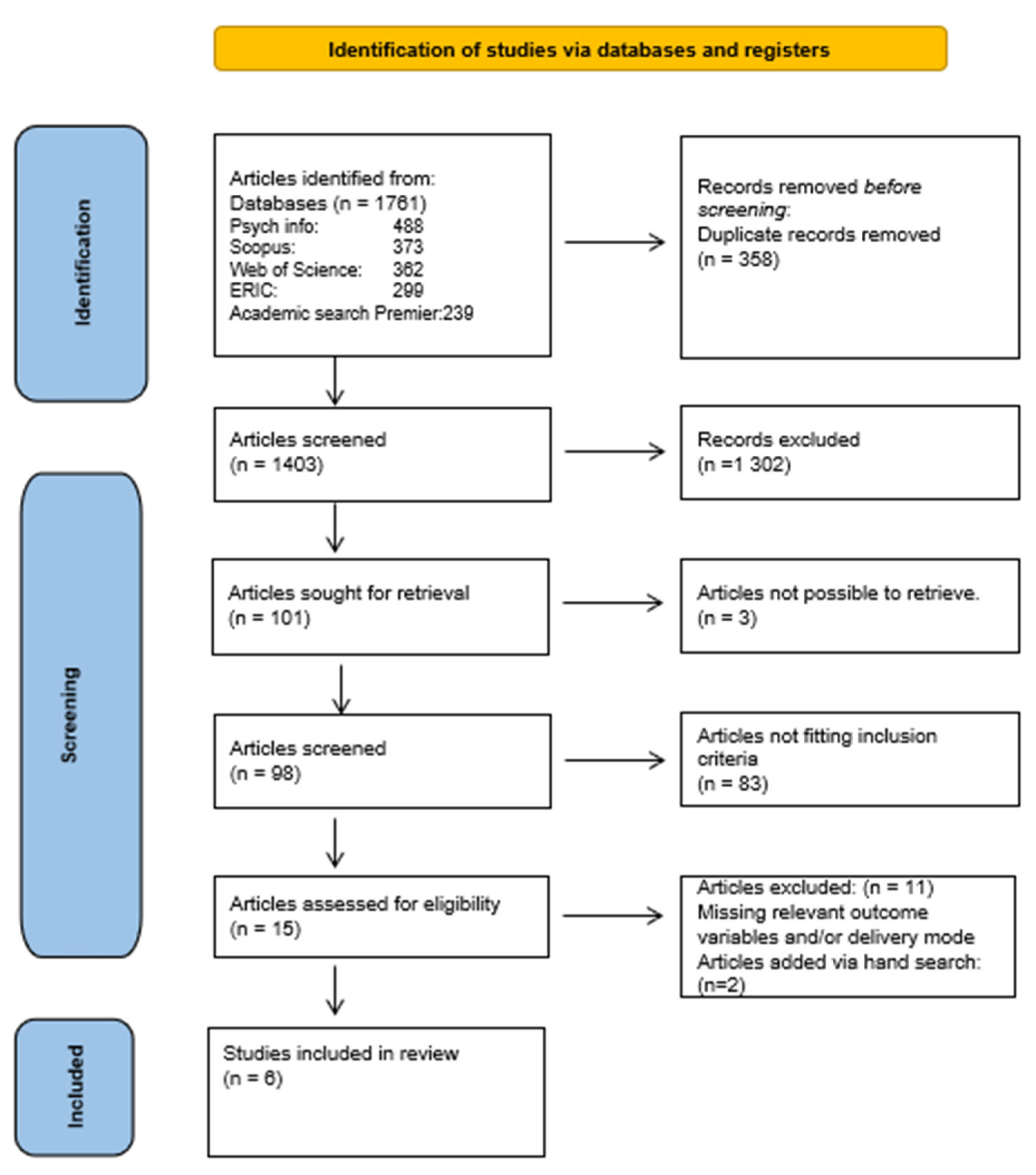

3.1. Study Design, Data Sources and Search Strategy

- All Fields (teacher* or instructor* or lecturer*)

- All fields (intervention* or rct or “control trial*” or course or program)

- Title (Work NEAR/5 Engagement) OR (Job NEAR/5 Engagement) OR (Burnout)

3.2. Study Selection and Quality Appraisal

3.3. Data Extraction

4. Results

4.1. Study Characteristics and Quality Assessment

Design, Countries, Sample Sizes, and Quality Assessment (MMAT)

4.2. Sample Recruitment and Inclusion Criteria for Participation in the Studies

4.3. Covariates Age and Sex on Burnout

4.4. How Were the Interventions Delivered?

4.5. Duration and Dosage of the Interventions

4.6. Analyzing Core Components Using the JD-R Theory

4.7. Effects of Interventions on Burnout Measures

4.8. Fidelity Measures and Use of Control Groups

4.9. Summary of Main Findings

5. Discussion

Dosage, Core Components, and Effects on Burnout

6. Implementation of the Interventions

6.1. Mode of Digital Delivery and Group Discussions

6.2. Fidelity Measures and Use of Control Groups in the Studies

6.3. Limitations

6.4. Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| JD-R | Job Demands–Resources Theory |

| ICD-11 | International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision |

| MBIs | Mindfulness-Based Interventions |

| UWES | Utrecht Work Engagement Scale |

| PR | Personal Resources |

| JR | Job Resources |

| JD | Job Demands |

| SEL | Social–Emotional Learning |

| EI | Emotional Intelligence |

| Org. skills | Organizational Skills |

| Technostress | Technology-Induced Stress |

| MBI | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| ηρ2 | Partial Eta Squared |

| Cohen’s d | Cohen’s d Statistic |

| β | Beta Coefficient |

| SE | Standard Error |

| JITAIs | Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| SEC | Social and Emotional Competence |

| EFL | Emotional Freedom Techniques |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PICO | Population, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes |

| CG | Control Group |

| IG | Intervention Group |

| ERIC | Education Resources Information Center |

| Psych Info | Psychological Information Database |

| MOM | Mindfulness-Oriented Meditation |

| IBSR | Inquiry-Based Stress Reduction |

| Scopus | Abstract and Citation Database |

| EPPI | Evidence for Policy and Practice Information |

| MBI-ES | Maslach Burnout Inventory-Educators Survey |

Appendix A. Search Strings and Databases

| Database | Specified Search String | Comments |

| ERIC | teacher* AND intervention* And (“job engagement” OR burnout) | Includes search in title, abstract and text |

| SOCindex: | TI teacher* AND AB intervention* AND AB (“job engagement” or burnout | |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (teacher* AND intervention* AND “Job engagement” OR burnout) teacher* AND intervention* OR rct OR randomized OR control OR trial OR course AND “job engagement” OR burnout | |

| Web of Science: | TI Teacher* AND AB intervention* AND AB “Job engagement” OR AB burnout | |

| JSTOR: | TI Teacher* AND intervention* AND “job engagement” OR burnout | Includes search in title, abstract and text |

| PsychINFO | Exp Workplace Intervention/or exp School Based Intervention/or intervention*.mp. or exp intervention/AND teacher*.mp. AND exp Job Involvement/or exp Job Satisfaction/or exp Employee Engagement/or exp Psychological Engagement/or “Job engagement”.mp. OR burnout.mp. or exp Occupational Stress/ | |

| Academic search ultimate | teacher* AND intervention* AND DE “JOB involvement” OR DE “JOB satisfaction” OR DE “JOB satisfaction testing” OR DE “PSYCHOLOGICAL burnout” OR DE “PSYCHOLOGICAL burnout prevention” | |

| * is used to allow for several endings of the keywords. | ||

References

- Agyapong, B., Brett-MacLean, P., Burback, L., Agyapong, V. I. O., & Wei, Y. (2023). Interventions to reduce stress and burnout among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(9), 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L., & Wei, Y. (2022). Stress, burnout, anxiety, and depression among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahola, K., Toppinen-Tanner, S., & Seppänen, J. (2017). Interventions to alleviate burnout symptoms and to support return to work among employees with burnout: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Burnout Research, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S. F., Wetherell, M. A., & Smith, M. A. (2020). Online writing about positive life experiences reduces depression and perceived stress reactivity in socially inhibited individuals. Psychiatry Research, 284, 112697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansley, B. M., Houchins, D. E., Varjas, K., Roach, A., Patterson, D., & Hendrick, R. (2021). The impact of an online stress intervention on burnout and teacher efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 98, 103251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avola, P., Soini-Ikonen, T., Jyrkiäinen, A., & Pentikäinen, V. (2025). Interventions to teacher well-being and burnout a scoping review. Educational Psychology Review, 37(1), 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2023). Burnout and work engagement: The JD-R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2020). Job demands-resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 33(4), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 22(3), 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista, T. G., Roman, G., Khan, M., Lee, M., Sahbaz, S., Duthely, L. M., Knippenberg, A., Macias-Burgos, M. A., Davidson, A., Scaramutti, C., Gabrilove, J., Pusek, S., Mehta, D., & Bredella, M. A. (2023). What is well-being? A scoping review of the conceptual and operational definitions of occupational well-being. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 7, e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasé, K., & Fixsen, D. (2013). Core intervention components: Identifying and operationalizing what makes programs work. In ASPE research brief. US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Bondanini, G., Giorgi, G., Ariza-Montes, A., Vega-Muñoz, A., & Andreucci-Annunziata, P. (2020). Technostress dark side of technology in the workplace: A scientometric analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, K. (2020). Fidelity. In P. Nilsen, & S. A. Birken (Eds.), Handbook on implementation science (pp. 291–316). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, V. S., Guerrero, E., Chambel, M. J., & González-Romá, V. (2021). Personal and organizational resources and work engagement: A cross-national study. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 36(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chari, R., Chang, C. C., Sauter, S. L., Petrun Sayers, E. L., Cerully, J. L., Schulte, P., Schill, A. L., & Uscher-Pines, L. (2018). Expanding the paradigm of occupational safety and health: A new framework for worker well-being. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(7), 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J. (2020). Teacher well-being: The importance of teacher-student relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 32(2), 457–477. [Google Scholar]

- Collie, R. J. (2025). Teachers’ perceived social-emotional competence: A personal resource linked with well-being and turnover intentions. Educational Psychology. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2015). School climate and social-emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(4), 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, E., & Yovanoff, P. (1996). Supporting professionals-at-risk: Evaluating interventions to reduce burnout and improve retention of special educators. Exceptional Children, 62(4), 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G. (2014). The new statistics: Why and how. Psychological Science, 25(1), 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domitrovich, C. E., Bradshaw, C. P., Poduska, J. M., Hoagwood, K., Buckley, J. A., Olin, S. S., Romanelli, L. H., Leaf, P. J., Greenberg, M. T., & Ialongo, N. S. (2008). Maximizing the implementation quality of evidence-based preventive interventions in schools: A conceptual framework. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 1(3), 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2015). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, P. D. (2010). The essential guide to effect sizes: Statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R., Murphy, S., & Scourfield, J. (2022). Implementation of school-based prevention programs: Lessons for future research and practice. Prevention Science, 23(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Falloon, G. (2020). From digital literacy to digital competence: The teacher digital competency (TDC) framework. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68, 2449–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixsen, D., & Blasé, K. (2020). Active Implementation Frameworks. In P. Nilsen, & S. A. Birken (Eds.), Handbook on implementation science (pp. 62–87). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, A. J. (2016). Applying critical realism in qualitative research: Methodology meets method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(2), 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S. L., & Mash, E. J. (1999). Assessing social validity in clinical treatment research: Issues and procedures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(3), 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. (2013). Stratosphere: Integrating technology, pedagogy, and change knowledge. Pearson Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Roma, V., Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Lloret, S. (2005). Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2017). An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Granziera, H., Collie, R., & Martin, A. (2020). Understanding Teacher Wellbeing Through Job Demands-Resources Theory. In C. F. Mansfield (Ed.), Cultivating Teacher Resilience. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S. L., Teo, S. T., Pick, D., Roche, M., & Newton, C. J. (2016). Psychological capital as a personal resource in the JD-R model. Personnel Review, 45(5), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagermoser Sanetti, L. M., Boyle, A. M., Magrath, E., Cascio, A., & Moore, E. (2021). Intervening to decrease teacher stress: A review of current research and new directions. Contemporary School Psychology, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43(6), 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G. E., & Hord, S. M. (2020). Implementing change: Patterns, principles, and potholes. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen, J., Roland, P., & Ertesvåg, S. K. (2025). The support system matters: Facilitator fidelity to planned pre-intervention training for teachers. Global Implementation Research and Applications, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76(5), 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J., Yin, H., Wang, W., & Zhang, J. (2020). Job demands and resources as antecedents of university teachers’ exhaustion, engagement and job satisfaction. Educational Psychology, 40(3), 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T., & Waber, J. (2021). Teacher well-being: A systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educational Research Review, 34, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidajat, M., Sari, R. F., & Sari, D. P. (2023). Mindfulness-based interventions for teacher burnout: A systematic review. Journal of Educational Psychology, 115(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (Eds.). (2008). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.0.1). The Cochrane Collaboration. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., Altman, D. G., Barbour, V., Macdonald, H., Johnston, M., Lamb, S. E., Dixon-Woods, M., McCulloch, P., Wyatt, J. C., Chan, A., & Michie, S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’cAthain, A., Rousseau, M., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, W. K., & Tarter, C. J. (1992). Measuring the health of the school climate: A conceptual framework. NASSP Bulletin, 76(547), 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, N., Lendrum, A., Ashworth, E., Frearson, K., Buck, R., & Kerr, K. (2016). Implementation and process evaluation (IPE) for interventions in education settings: An introductory handbook. Education Endowment Foundation, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. C. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 837–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iancu, S. C., Rusu, A., & Maricuțoiu, L. P. (2018). The effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing teacher burnout: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. T., & Solheim, O. J. (2020). Teacher burnout and student-teacher relationships: The role of teacher self-efficacy. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenegger, H. C., Marques, M. D., Becker, L., Rohleder, N., Nowak, D., Wright, B. J., & Weigl, M. (2024). Prospective associations of technostress at work, burnout symptoms, hair cortisol, and chronic low-grade inflammation. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 117, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katie, B. (2002). Loving what is: Four questions that can change your life. Harmony Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kintu, M. J., Zhu, C., & Kagambe, E. (2017). Blended learning effectiveness: The relationship between student characteristics, design features and outcomes. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, M. A. (2020). Adaptation. In P. Nilsen, & S. A. Birken (Eds.), Handbook on implementation science (pp. 317–332). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, R. M., Yerdelen, S., & Durksen, T. L. (2013). Teacher engagement at work: An integrative review of the literature. Educational Psychology Review, 25(3), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Klingbeil, D. A., & Renshaw, T. L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for teachers: A meta-analysis of the emerging evidence base. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(4), 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolfschoten, G. L., Niederman, F., Briggs, R. O., & de Vreede, G.-J. (2012). Facilitation roles and responsibilities for sustained collaboration support in organizations. Journal of Management Information Systems, 28(4), 129–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzelmann, A., Rigotti, T., & Crane, M. F. (2025). Latent profiles of challenge, hindrance, and threat appraisals on time pressure and job complexity: Antecedents and outcomes. Australian Journal of Management, 50(2), 431–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S. N., Jeon, L., Sproat, E. B., Brothers, B. E., & Buettner, C. K. (2020). Social Emotional Learning for Teachers (SELF-T): A short-term, online intervention to increase early childhood educators’ resilience. Early Education and Development, 31(7), 1112–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping (Vol. 464). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Leko, M. M. (2014). The value of qualitative methods in social validity research. Remedial and Special Education, 35(5), 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Towards an understanding of teacher attrition: A meta-analysis of burnout, job satisfaction, and teachers’ intentions to leave. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricuțoiu, L. P., Valache, D. G., Popescu, B. D., Pap, Z., Ștefancu, E., Mladenovici, V., Ilie, M., & Vîrgă, D. (2023). Is teachers’ well-being associated with students’ school experience? A meta-analysis of cross-sectional evidence. Educational Psychology Review, 35(1), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Martela, F., & Pessi, A. B. (2018). Significant work is about self-realization and broader purpose: Defining the key dimensions of meaningful work. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Schwab, R. L. (1986). Maslach burnout inventory-educators survey (MBI-ES). In C. Maslach, S. E. Jackson, & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), MBI manual (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matiz, A., Fabbro, F., Paschetto, A., Cantone, D., Paolone, A. R., & Crescentini, C. (2020). Positive impact of mindfulness meditation on mental health of female teachers during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallum, F. (2020). Teacher well-being: The importance of positive relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 32(2), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, C. J. (2019). Teacher stress: Balancing demands and resources. Educational Psychology Review, 31(1), 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mérida-López, S., Extremera, N., & Rey, L. (2022). Emotional intelligence and teacher burnout: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshe, I., Terhorst, Y., Philippi, P., Domhardt, M., Cuijpers, P., Cristea, I., Pulkki-Råback, L., Baumeister, H., & Sander, L. B. (2021). Digital interventions for the treatment of depression: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(8), 749–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghieh, A., Montgomery, P., Bonell, C. P., Thompson, M., & Aber, J. L. (2015). Organisational interventions for improving wellbeing and reducing work-related stress in teachers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(4), CD010306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahum-Shani, I., Smith, S. N., Spring, B. J., Collins, L. M., Witkiewitz, K., Tewari, A., & Murphy, S. A. (2018). Just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: Key components and design principles for ongoing health behavior support. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52(6), 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, J. M., O’Moore, K., Tang, S., Christensen, H., & Faasse, K. (2021). Acute mental health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. PLoS ONE, 16(7), e0236562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S., Roberto, M. S., Veiga-Simão, A. M., & Marques-Pinto, A. (2022). Effects of the A+ intervention on elementary-school teachers’ social and emotional competence and occupational health. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 957249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagán-Garbín, I., Méndez, I., & Martínez-Ramón, J. P. (2024). Exploration of stress, burnout and technostress levels in teachers. Prediction of their resilience levels using an artificial neuronal network (ANN). Teaching and Teacher Education, 148, 104717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., A Akl, E., E Brennan, S., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, F. L., Koestner, R., Lecours, S., Beaulieu-Pelletier, G., Bois, K., & Bellerose, J. (2022). The role of episodic memories in current and future well-being. Journal of Personality, 90(1), 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, J. A., & Cohen, L. (2010). Resilience: A definition in context. Australian Community Psychologist, 22(1), 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pozo-Rico, T., Gilar-Corbí, R., Izquierdo, A., & Castejón, J. L. (2020). Teacher training can make a difference: Tools to overcome the impact of COVID-19 on primary schools. An experimental study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattrie, L., & Kittler, M. (2014). The Job Demands-Resources model and the international work context: A systematic review. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 2(3), 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Round, R. L., Brown, J. L., & Engle, J. L. (2022). Positive expressive writing for reducing stress and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M., Llorens, S., & Cifre, E. (2013). The dark side of technologies: Technostress among users of information and communication technologies. International Journal of Psychology, 48(3), 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagioni, D. A. J., Melanda, F. N., Mesas, A. E., González, A. D., Gabani, F. L., & Andrade, S. M. (2017). Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE, 12(10), e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. (2017). Applying the Job Demands-Resources model: A ‘how to’ guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organizational Dynamics, 46(2), 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2003). Utrecht work engagement scale: Preliminary manual. Occupational Health Psychology Unit, Utrecht University. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Hakanen, J., & Shimazu, A. (2023). Burning questions in burnout research (pp.127-148). In N. DeCuyper, E. Selenko, M. Euewema, & W. B. Schaufeli (Eds.), Job insecurity, precarious employment and burnout. Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In G. F. Bauer, & O. Hämmig (Eds.), Bridging occupational, organizational and public health: A transdisciplinary approach (pp. 1–23). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schleiker, A. (2018). Valuing our teachers and raising their status: How communities can help. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Shirom, A., Toker, S., Melamed, S., Berliner, S., & Shapira, I. (2005). Burnout and health review: Current knowledge and future research directions. In A. S. G. Antoniou, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Research companion to organizational health psychology (pp. 1–23). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2018). Job demands and job resources as predictors of teacher motivation and well-being. Educational Psychology, 38(3), 1251–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S. C., Chandra, S., & Shirish, A. (2015). Technostress creators and job outcomes: Theorising the moderating influence of personality traits. Information Systems Journal, 25(4), 355–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, L., Haverinen, K., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2022, April). Differences in teacher burnout between schools: Exploring the effect of proactive strategies on burnout trajectories. In Frontiers in education (Vol. 7, p. 858896). Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar]

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2016). The longitudinal impact of a job crafting intervention. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(3), 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingerden, J., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2017). The impact of personal resources and job crafting interventions on work engagement and performance. Human Resource Management, 56(1), 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von der Embse, N. P., Mankin, A., Kilgus, M., & Segool, N. (2019). Teacher stress interventions: A systematic review. Psychology in the Schools, 56(3), 1328–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R., & Michie, S. (2016). A guide to development and evaluation of digital behavior change interventions in healthcare. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, H. (2013). An introduction to the use of randomised control trials to evaluate development interventions. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 5(1), 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M. M. (1978). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11(2), 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, K. (2014). Main factors of teachers’ professional well-being. Educational Research and Reviews, 9(6), 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadok-Gurman, T., Jakobovich, R., Dvash, E., Zafrani, K., Rolnik, B., Ganz, A. B., & Lev-Ari, S. (2021). Effect of Inquiry-Based Stress Reduction (IBSR) intervention on well-being, resilience, and burnout of teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarate, K., Maggin, D. M., & Passmore, A. (2019). Meta-analysis of mindfulness training on teacher well-being. Psychology in the Schools, 56(10), 1700–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| The type of participants is in-service teachers teaching in grades 1–13 (including Kindergarten in the US and in Australia) | Type of Participants: All occupational groups other than teachers working in-service. |

| Context: Digital and digitalized interventions implemented for in-service teachers. | Types of Interventions: Professional well-being interventions that do not include digital technology in the delivery method. |

| Types of Interventions: Both digitalized and digital interventions aim to increase teachers’ professional well-being. These include technology, online apps, PDFs, CDs, and game-based interventions. | Types of Studies: Qualitative studies and conceptual/theoretical papers will be excluded from the review. |

| Types of Studies: Quasi-experimental and experimental studies will be included in the review. | Comparator/control: Studies with no control or pre-and post-test. |

| Comparator/control: The studies included will include a randomized control group, an assigned control group, or only pre-and post-test measures. | Type of Publication: Grey literature, dissertations, not peer-reviewed articles, reports, or articles in languages other than English. |

| All years of publications. | Outcome Measures: Outcome measures outside teachers’ job engagement and/or burnout. |

| Type of Publication: Full-length empirical peer-reviewed articles published in peer-reviewed journals, with no date restrictions. | |

| Language: English | |

| Outcome Measures: Interventions to promote teachers’ professional well-being with job engagement and/or burnout outcome variables. |

| Author, Country, Publication Year | Study Details | Intervention Details | Underlying Theory and Definition of Burnout | Main Effects and Burnout Scale Used Relevant to This Systematic Review (Other Effects were Found but Not Reported Here): |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ansley et al., 2021, USA) | Type: randomized controlled trial (RCT) Participants: 51 Women (W): 10 Men (M): 41 Measurement: Pre- and Posttest Digital modalities: Video files/audio files, written instructions, online open learning platform Other Materials: Course guide, workbook, course schedule, and suggested pacing. | Duration in weeks: 4 Dosage of intervention: 30 min per module Intervention Group (IG): 2 modules weekly (total hours required: 4; participants reported 8 h a week to practice coping strategies, although they were not mandatory) Control Group (CG): No treatment was received. Coach/Facilitator: No Synchronous hrs.: No Asynchronous hrs.: Yes Goal/focus: Teaching teachers coping resources to manage stress (Lazarus, 1984) and ameliorate social–emotional competencies that promote positive learning experiences, increase teacher efficacy, and lower burnout rates through mindfulness, relaxation, cognitive restructuring, social support, and physical exercise. Intervention feasibility: Treatment acceptability (7 items scale): Time engaged in independent practicing coping strategies weekly (in between work) Support: After 48 h, an email is sent out, followed by a reminder again after 48 h. If no response is received, the participant is withdrawn. Enrolled received a welcome email and, course pacing guide, and optional workbook. Weekly emails with updates about progress, and reminder emails if behind. Five weeks to complete the program. | Underlying theory: Based on previous stress reduction interventions, including mindfulness, relaxation, and cognitive restructuring for teachers. Burnout definition: Maslach’s three dimensions: Emotional exhaustion (EE), personal accomplishment (PA), depersonalization (DP) (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) | Effect: No significant effects. Burnout scale: Masclach burnout inventory-educator survey (MBI-ES; Maslach et al., 1986) |

| (Matiz et al., 2020, Italy) | Type: Quasi-experimental Participants: W 58 Measurement: Pre- and Posttest Digital modalities: Audio recording, email, calls, videos sent via the internet Other Materials: Audio files, books, and articles per request from the participants. | Duration in weeks: 8 Dosage of intervention: IG and CG: 8 group meetings (2 h per meeting), two face-to-face meetings, and 6 video lessons delivered via the Internet. Daily meditations are 30 min, and activity is reported every two weeks. Based on baseline scores on resilience, participants were divided into low (LR) and high-resilience (HR) groups. Coach/Facilitator: Facilitator Synchronous hrs.: Yes Asynchronous hrs.: Yes Goal/focus: Test the MOM on anxiety, depression, affective empathy, emotional exhaustion, psychological well-being, interoceptive awareness, character traits, and mindfulness. Support: Phone calls, discussions, books, and articles to read per request. | Underlying theory: Mindfulness-Oriented Meditation (MOM) Burnout definition: Maslach’s three dimensions. (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) | Effect: The LR group significantly lowered EE. The HR group experienced higher PA. DP no change. ηρ2 EE = 0.240 significant change over time, and change overall decrease Burnout scale: Italian translation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Educators Survey (MBI-ES) (Maslach et al., 1986). |

| (Oliveira et al., 2022, Portugal) | Type: Quasi-experimental Participants: 81 W: 78 M: 3 Measurement: Pre- and post-test. 3 Months- and 6 months after posttest. Digital modalities: Zoom/Teams, Moodle platform. Other Materials: None reported. | Duration in weeks: 10 Dosage of intervention: Weekly 2.5-h group sessions and 2.5 h asynchronous hours for ten weeks. (Combined 50 h) IG: Three clusters of teachers according to perceived organizational climate CG: No treatment Coach/Facilitator: Trained and certified instructor Synchronous hrs.: Yes Asynchronous hrs.: Yes Goal/focus: Increasing social and emotional competence and occupational health., e.g., increased self-regulation, positive relationship, conflict management skills and increased emotional well-being, decreased occupational stress, and emotional exhaustion symptoms. Support: No specific support was reported in the article. | Underlying theory: SEL for teachers based on three main theoretical frameworks: Emotional intelligence theory (Salovey & Mayer, 1990), the Transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus, 1984), and Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Burnout definition: Emotional exhaustion is emphasized (Maslach et al., 1996). | Effect: Significant effect on EE. DP and PA are not reported. Beta = −0.84, SE = 0.40, 95% Burnout scale: Maslach burnout inventory-Educators survey (Maslach et al., 1996; Portuguese version). |

| (Pozo-Rico et al., 2020, Spain) | Type: RCT Participants: 141 W: 80 M:61 Measurement: Pre- and Posttest Digital modalities: Moodle platform for pre and posttest. E-learning Moodle platform for discussions, online teaching. Other Materials: Not reported. | Duration in weeks: 14 Dosage of intervention: IG: Not reported CG: No treatment. Coach/Facilitator: Trainer Synchronous hrs.: Yes Asynchronous hrs.: No Goal/focus: Coping with stress, preventing burnout, improving their information and communications technology, and introducing the principles of EI in the classroom. Support: Not specified in the article. | Underlying theory: Introducing emotional intelligence to reduce stress and prevent burnout in teachers for their own well-being and to introduce it into the classrooms. Burnout definition: Maslach three dimensions (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) | Effect: Significant decrease in EE and DP, and increase in PA. ηρ2 EE = 0.63, DP = 0.76, PA = 0.46 Burnout scale: Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; 22-item), (Maslach et al., 1996). |

| (Round et al., 2022, UK) | Type: RCT Participants: 66 W: 54 (35 teachers) M: 12 The remaining participants were fulltime workers of other occupations. Measurement: Pre- and Posttest, and anxiety test before and after each of the three days of writing. Digital modalities: Not specified, only via the internet or on an online platform Other Materials: None specified. | Duration in weeks: 0.4 Dosage of intervention: IG: 20 min positive expressive writing in three days (combined 60 min) CG: 20 min neutral writing in three days Coach/Facilitator: No Synchronous hrs.: No Asynchronous hrs.: Yes Goal/focus: To test positive expressive writing on burnout, job satisfaction, anxiety, perceived stress, and self-reported physical symptoms. To measure baseline differences in burnout and perceived stress between teachers and non-teachers. Support: Emails were sent out to remind the participants of participation in the study. | Underlying theory: Written emotional disclosure (Pennebaker, 1997). Positive writing for reducing stress and anxiety and increasing well-being. (Allen et al., 2020). Burnout definition: Maslach three dimensions (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) | Effect: No significant or interactive effects on burnout for the teachers, nor any other difference for the participants of other occupations. Burnout scale: Maslach burnout inventory MBI, three dimensions (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) |

| (Zadok-Gurman et al., 2021, Israel) | Type: Quasi-experimental Participants: 60 W: 58 M: 9 Measurement: Pre- and Posttest Digital modalities: Not specified, only via the internet or an online platform. Other Materials: No other materials reported. Control group received an IBSR book upon posttest completion. | Duration in weeks: 20 Dosage of intervention: IG:10 biweekly meetings 2.5 h/meeting and biweekly individual sessions with a facilitator 1h/session for 20 weeks (combined 35 hrs). CG: Participated in other courses unrelated to the intervention. Coach/Facilitator: Facilitator Synchronous hrs.: Yes Asynchronous hrs.: Yes Goal/focus: Increase teachers’ well-being and assess the intervention’s effect on resilience, burnout, mindfulness, and stress among teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Support: No specific support reported. | Underlying theory: Blended inquiry-based stress reduction (IBSR), mindfulness and cognitive reframing intervention on teachers’ well-being. Burnout definition: Maslach three dimensions (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) | Effect: Significant decrease on EE. PA had no change, and DP was not measured. EE: Cohens d = 0.752 Burnout scale: Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), Maslach et al. (1996). |

| Studies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. (Round et al., 2022) | 2. (Ansley et al., 2021) | 3. * (Matiz et al., 2020) | 4. (Oliveira et al., 2022) | 5. * (Zadok-Gurman et al., 2021) | 6. (Pozo-Rico et al., 2020) | ||

| Digital modalities | Videos/audio files | x | x | ||||

| Zoom/Teams e-learning Moodle platform | x | x | |||||

| Not specified, only via the internet or on an online platform | x | x | x | ||||

| Training hours | Training during asynchronous hours | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Training during synchronous hours | x | x | x | x | |||

| Group training format | Group discussions w/facilitator or coach online meeting | x | x | x | |||

| Group discussions w/facilitator or coach physical meeting | x | x | |||||

| Individual training/ homework | Individual training/ homework | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Materials and communication | E.g., emails, materials, articles, books. | x | x | x | |||

| Study | Personal Resources | Job Resources | Job Demand | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Mastery | SEL/ EI | PE | ICT | Org. Skills | Techno Stress | |

| (Ansley et al., 2021) | x | x | x | |||

| (Matiz et al., 2020) | x | |||||

| (Oliveira et al., 2022) | x | x | ||||

| (Pozo-Rico et al., 2020) | x | x | x | x | x | |

| (Round et al., 2022) | x | |||||

| (Zadok-Gurman et al., 2021) | x | |||||

| Study | Duration of Days | Dosage Required Hours | Content Focused 1, 2 | JD-R | Effects and p-Value on Burnout | Fidelity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * (Round et al., 2022) | 3 | 1 | 1 | PR | No significant effect. | The computer program only allowed 20 min of writing activity at a time. |

| * (Ansley et al., 2021) | 28 | 4 | 1 | PR | No significant effect. Emotional exhaustion: ηρ2 = 0.09 (p = 0.051) Depersonalization: ηρ2 = 0.07 (p = 0.071) Personal Accomplishment: ηρ2 = 0.05 (p = 1.30) | Two independent reviewers analyzed the program’s content using a fidelity checklist developed by the first author. |

| (Matiz et al., 2020) | 56 | 16 | 1 | PR | Emotional exhaustion: ηρ2 = 0.240 (p = 0.001) Group Time: ηρ2 = 0.108 (p = 0.01) Personal accomplishment: 0.157 (p = 0.002) | Self-recorded meditation practices in diaries |

| (Oliveira et al., 2022) | 70 | 50 | 1 and 2 | PR, JR | Emotional exhaustion β = −0.84 significant, SE = 0.40, 95%. | A trained observer at all 30 training sessions completed at SSOG. The second trainer filled in 1/3 of the time. |

| (Pozo-Rico et al., 2020) | 98 | *14 modules, but no specified length for each | 1 and 2 | PR, JR, and JD | Emotional exhaustion: ηρ2 = 0.73 Depersonalization: ηρ2 = 0.79 Personal accomplishment: ηρ2 = 0.97 (p = 0.001) | None reported. |

| (Zadok-Gurman et al., 2021) | 140 | 45 | 1 | PR | Emotional exhaustion: d = 0.752 (p = 0.01) Personal accomplishment: Borderline significant | Reports that all lessons were standardized and assessed. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lillelien, K.; Jensen, M.T. Digital and Digitized Interventions for Teachers’ Professional Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Work Engagement and Burnout Using the Job Demands–Resources Theory. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070799

Lillelien K, Jensen MT. Digital and Digitized Interventions for Teachers’ Professional Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Work Engagement and Burnout Using the Job Demands–Resources Theory. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):799. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070799

Chicago/Turabian StyleLillelien, Kaja, and Maria Therese Jensen. 2025. "Digital and Digitized Interventions for Teachers’ Professional Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Work Engagement and Burnout Using the Job Demands–Resources Theory" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070799

APA StyleLillelien, K., & Jensen, M. T. (2025). Digital and Digitized Interventions for Teachers’ Professional Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Work Engagement and Burnout Using the Job Demands–Resources Theory. Education Sciences, 15(7), 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070799