The Mediation Role of School Alienation Between Perceptions of the School Atmosphere and School Refusal in Italian Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adam, F. F. (2023). Self-dissociation as a predictor of alienation and sense of belonging in university students. Journal of Family Counseling and Education, 8(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.-A., & Boyle, C. (2022). School belonging and student engagement: The critical overlaps, similarities, and implications for student outcomes. In A. L. Reschly, & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 133–154). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, I. L. d. L., Rego, J. F., Teixeira, A. C. G., & Moreira, M. R. (2022). Social isolation and its impact on child and adolescent development: A systematic review. Revista Paulista de Pediatria, 40, e2020385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenbaugh, R. J., Engel, D. E., & Martin, D. T. (1995). Caring for kids: A critical study of urban school leavers. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Atiq, H. (2023). The impact of teachers’ servant leadership on students’ alienation: An empirical evidence from the university students in Pakistan. Pakistan Languages and Humanities Review, 7(1), 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baafi, R. K. A. (2020). School physical environment and student academic performance. Advances in Physical Education, 10(2), 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Edwards, J. R. (1998). A general approach for representing constructs in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 1(1), 45–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J. A. (1998). Are we missing the forest for the trees? Considering the social context of school violence. Journal of School Psychology, 36(1), 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardach, L., Röhl, S., Oczlon, S., Schumacher, A., Lüftenegger, M., Lavelle-Hill, R., Schwarzenthal, M., & Zitzmann, S. (2024). Cultural diversity climate in school: A meta-analytic review of its relationships with intergroup, academic, and socioemotional outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 150(12), 1397–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, I. (1997). School refusal and truancy. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 76(2), 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. R., Higgins, K., & Paulsen, K. (2003). Adolescent alienation: What is it and what can educators do about it? Intervention in School and Clinic, 39(1), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhs, E. S., & Ladd, G. W. (2001). Peer rejection as antecedent of young children’s school adjustment: An examination of mediating processes. Developmental Psychology, 37(4), 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, N., Quigg, Z., Bates, R., Jones, L., Ashworth, E., Gowland, S., & Jones, M. (2022). The contributing role of family, school, and peer supportive relationships in protecting the mental wellbeing of children and adolescents. School Mental Health, 14(3), 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzai, C., Filippello, P., Caparello, C., & Sorrenti, L. (2022). Need-supportive and need-thwarting interpersonal behaviors by teachers and classmates in adolescence: The mediating role of basic psychological needs on school alienation and academic achievement. Social Psychology of Education, 25(4), 881–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzai, C., Sorrenti, L., Tripiciano, F., Orecchio, S., & Filippello, P. (2021). School alienation and academic achievement: The role of learned helplessness and mastery orientation. School Psychology, 36(1), 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar, C. (2013). The relationship between the perceptions of the fairness of the learning environment and the level of alienation. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 50, 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Canlı, S., & Demirtaş, H. (2022). The correlation between social justice leadership and student alienation. Educational Administration Quarterly, 58(1), 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, R., Iannoni, M. E., Curto, M., Biagiarelli, M., Listanti, G., Andraos, M. P., Mantovani, B., Farulla, C., Pelaccia, S., Grosso, G., Speranza, A. M., & Sarlatto, C. (2022). School refusal behavior: Role of personality styles, social functioning, and psychiatric symptoms in a sample of adolescent help-seekers. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 19(1), 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffman, D. L., & MacCallum, R. C. (2005). Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40(2), 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., Mccabe, E. M., Michelli, N. M., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: Research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 111(1), 180–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, B., Martinez-Monteagudo, M. C., Ruiz-Esteban, C., & Rubio, E. (2019). Latent class analysis of school refusal behavior and its relationship with cyberbullying during adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demanet, J., & Van Houtte, M. (2012). School belonging and school misconduct: The differing role of teacher and peer attachment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(4), 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, E., & Kazu, H. (2022). Examination of the relationships between secondary school students’ social media attitudes, school climate perceptions and levels of alienation. Athens Journal of Education, 9(2), 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devenney, R., & O’Toole, C. (2021). ‘What kind of education system are we offering’: The views of education professionals on school refusal. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 10(1), 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donat, M., Gallschütz, C., & Dalbert, C. (2018). The relation between students’ justice experiences and their school refusal behavior. Social Psychology of Education, 21, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Mac Iver, D. (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48(2), 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, H. L., Costello, J. E., & Angold, A. (2003). School refusal and psychiatric disorders: A community study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(7), 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, S., & Lareau, A. (2021). Hostile ignorance, class, and same-race friendships: Perspectives of working-class college students. Socius, 7, 23780231211048305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Sogorb, A., Sanmartín, R., Vicent, M., & Gonzálvez, C. (2021). Identifying profiles of anxiety in late childhood and exploring their relationship with school-based distress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippello, P., Buzzai, C., Costa, S., & Sorrenti, L. (2019). School refusal and absenteeism: Perception of teacher behaviors, psychological basic needs, and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, J. D., & Rock, D. A. (1997). Academic success among students at risk for school failure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finning, K., Ukoumunne, O. C., Ford, T., Danielson-Waters, E., Shaw, L., Romero De Jager, I., Stentiford, L., & Moore, D. A. (2019). Review: The association between anxiety and poor attendance at school—A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24(3), 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, C. E., Horwitz, A., Thomas, A., Opperman, K., Gipson, P., Burnside, A., Stone, D. M., & King, C. A. (2017). Connectedness to family, school, peers, and community in socially vulnerable adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 81, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallé-Tessonneau, M., & Dahéron, L. (2020). «Je ne veux pas aller à l’école»: Perspectives actuelles sur le repérage du refus scolaire anxieux et présentation de la SChool REfusal EvaluatioN (SCREEN). Neuropsychiatrie de l’Enfance et de l’Adolescence, 68(6), 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallé-Tessonneau, M., & Gana, K. (2019). Development and validation of the school refusal evaluation scale for adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 44(2), 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzálvez, C., Díaz-Herrero, Á., Sanmartín, R., Vicent, M., Pérez-Sánchez, A. M., & García-Fernández, J. M. (2019). Identifying risk profiles of school refusal behavior: Differences in Social anxiety and family functioning among Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravett, K., & Winstone, N. E. (2022). Making connections: Authenticity and alienation within students’ relationships in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(2), 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazia, V., & Molinari, L. (2021). School climate research: Italian adaptation and validation of a multidimensional school climate questionnaire. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 39(3), 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjar, A., Grecu, A., Scharf, J., de Moll, F., Morinaj, J., & Hascher, T. (2021). Changes in school alienation profiles among secondary school students and the role of teaching style: Results from a longitudinal study in Luxembourg and Switzerland. International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjar, A., & Gross, C. (Eds.). (2016). Education systems and inequalities: International comparisons. Policy Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, E. C., Moore, K. A., Ling, T. J., McPhee-Baker, C., & Brown, B. V. (2009). Youth who are “disconnected” and those who then reconnect: Assessing the influence of family, programs, peers and communities. Child Trends, 37, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R. J., Snell, A. F., & Foust, M. S. (1999). Item parceling strategies in SEM: Investigating the subtle effects of unmodeled secondary constructs. Organizational Research Methods, 2(3), 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76(5), 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F., & Demïrtaş, H. (2021). Zorbalığa maruz kalmanin sinif iklimine ve okula yabancilaşmaya etkisi. İnönü Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 22(3), 2297–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T., & Hadjar, A. (2018). School alienation—Theoretical approaches and educational research. Educational Research, 60(2), 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T., & Hagenauer, G. (2010). Alienation from school. International Journal of Educational Research, 49(6), 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, K., & Marsh, H. W. (2004). The use of item parcels in structural equation modelling: Non-normal data and small sample sizes. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 57(2), 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havik, T., Bru, E., & Ertesvåg, S. K. (2015). School factors associated with school refusal- and truancy-related reasons for school non-attendance. Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal, 18(2), 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havik, T., & Ingul, J. M. (2021). How to understand school refusal. Frontiers in Education, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, N. M., Emmons, C., & Ben-Avie, M. (1997). School climate as a factor in student adjustment and achievement. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 8(3), 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendron, M., & Kearney, C. A. (2016). School climate and student absenteeism and internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems. Children & Schools, 38(2), 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. N., Gleason, K. A., & Zhang, D. (2005). Relationship influences on teachers’ perceptions of academic competence in academically at-risk minority and majority first grade students. Journal of School Psychology, 43(4), 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacobucci, D., Saldanha, N., & Deng, X. (2007). A meditation on mediation: Evidence that structural equations models perform better than regressions. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(2), 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A., & El Zaatari, W. (2020). The teacher–student relationship and adolescents’ sense of school belonging. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksen, S. G. (2007). The situational outlook questionnaire: Assessing the context for change. Psychological Reports, 100(2), 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B., & Stevens, J. J. (2006). Student achievement and elementary teachers’ perceptions of school climate. Learning Environments Research, 9(2), 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, D. M. (1990). How schools alienate students at risk: A model for examining proximal classroom variables. Educational Psychologist, 25(2), 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, C. A., Benoit, L., Gonzálvez, C., & Keppens, G. (2022). School attendance and school absenteeism: A primer for the past, present, and theory of change for the future. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1044608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, C. A., Lemos, A., & Silverman, J. (2004). The functional assessment of school refusal behavior. The Behavior Analyst Today, 5(3), 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, C. A., & Silverman, W. K. (1996). The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 3(4), 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishton, J. M., & Widaman, K. F. (1994). Unidimensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items: An empirical example. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 54(3), 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Knollmann, M., Reissner, V., & Hebebrand, J. (2019). Towards a comprehensive assessment of school absenteeism: Development and initial validation of the inventory of school attendance problems. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(3), 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Salle, T. P., Meyers, J., Varjas, K., & Roach, A. (2015). A cultural-ecological model of school climate. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 3(3), 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T., Hong, S. E., Kang, J., & Lee, S. M. (2023). Role of achievement value, teachers’ autonomy support, and teachers’ academic pressure in promoting academic engagement among high school seniors. School Psychology International, 44(6), 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, L., Green-Demers, I., & Pelletier, L. (2006). Why do high school students lack motivation in the classroom? Toward an understanding of academic amotivation and the role of social support. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(3), 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Gu, H., Zhao, X., & Wang, Y. (2021). What contributes to the development and maintenance of school refusal in Chinese adolescents: A qualitative study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 782605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, E., Traficante, D., Bettoni, R., Offredi, I., Giorgetti, M., & Vernice, M. (2019). The impact of school climate on well-being experience and school engagement: A study with high-school students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubienski, S. T., Lubienski, C., & Crane, C. C. (2008). Achievement differences and school type: The role of school climate, teacher certification, and instruction. American Journal of Education, 115(1), 97–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 4(1), 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, H., Brown, M. R., Amani Saribagloo, J., & Dadashzadeh, S. (2018). The role of school culture and basic psychological needs on Iranian adolescents’ academic alienation: A multi-level examination. Youth & Society, 50(1), 116–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameli, C., Grazia, V., Passini, S., & Molinari, L. (2022). Student perceptions of interpersonal justice, engagement, agency and anger: A longitudinal study for reciprocal effects. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 37(3), 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcin, K., Morinaj, I., & Hascher, T. (2019). The relationship between alienation from learning and student needs in Swiss primary and secondary schools. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogische Psychologie, 34(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, M. (2008). Item parceling in structural equation modeling: A primer. Communication Methods and Measures, 2(4), 260–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S., Reynolds, K. J., Lee, E., Subasic, E., & Bromhead, D. (2017). The impact of school climate and school identification on academic achievement: Multilevel modeling with student and teacher data. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, T., & Thomas, A. R. (1991). School climate and school culture. Journal of Educational Administration, 29(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKown, C., & Weinstein, R. S. (2008). Teacher expectations, classroom context, and the achievement gap. Journal of School Psychology, 46(3), 235–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinari, L., & Grazia, V. (2023a). A multi-informant study of school climate: Student, parent, and teacher perceptions. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 38(4), 1403–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, L., & Grazia, V. (2023b). Students’ school climate perceptions: Do engagement and burnout matter? Learning Environments Research, 26(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, L., Speltini, G., & Passini, S. (2013). Do perceptions of being treated fairly increase students’ outcomes? Teacher–student interactions and classroom justice in Italian adolescents. Educational Research and Evaluation, 19(1), 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morinaj, J., Hadjar, A., & Hascher, T. (2020). School alienation and academic achievement in Switzerland and Luxembourg: A longitudinal perspective. Social Psychology of Education, 23(2), 279–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morinaj, J., & Hascher, T. (2019). School alienation and student well-being: A cross-lagged longitudinal analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(2), 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morinaj, J., Marcin, K., & Hascher, T. (2019). School alienation and its association with student learning and social behavior in challenging times. In Motivation in education at a time of global change (Vol. 20, pp. 205–224). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M. K. C., Russell, P. S. S., Subramaniam, V. S., Nazeema, S., Chembagam, N., Russell, S., Shankar, S. R., Jakati, P. K., & Charles, H. (2013). ADad 8: School phobia and anxiety disorders among adolescents in a rural community population in India. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 80(2), 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochi, M., Kawabe, K., Ochi, S., Miyama, T., Horiuchi, F., & Ueno, S. (2020). School refusal and bullying in children with autism spectrum disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogaz, D. A. C. (2016). Multivariate approaches to school climate factors and school outcomes [Ph.D. thesis, University of Sussex]. Available online: https://sussex.figshare.com/articles/thesis/Multivariate_approaches_to_school_climate_factors_and_school_outcomes/23430830?file=41144336 (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Ooi, S. X., & Cortina, K. S. (2023). Cooperative and competitive school climate: Their impact on sense of belonging across cultures. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 8). Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, K. F. (2023). Teacher practice and students’ sense of belonging. In T. Lovat, R. Toomey, N. Clement, & K. Dally (Eds.), Second international research handbook on values education and student wellbeing (pp. 971–993). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhuswamy, M. (2018). To go or not to go: School refusal and its clinical correlates. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 54(10), 1117–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. (2018). Psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research (Volume 2, 5). R package version. RStudio, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, M. R., Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., White, M., & Salovey, P. (2012). Classroom emotional climate, student engagement, and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roff, S., & McAleer, S. (2001). What is educational climate? Medical Teacher, 23(4), 333–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Salter, D., Neelakandan, A., & Wuthrich, V. M. (2024). Anxiety and teacher-student relationships in secondary school: A systematic literature review. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G. D., Sardinha, S., & Reis, S. (2016). Relationships in inclusive classrooms. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 16(S1), 950–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, A., Morinaj, J., & Hascher, T. (2021). On the relation between school alienation and social school climate. Swiss Journal of Educational Research, 43(3), 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrenti, L., Caparello, C., Meduri, C. F., Fumia, A., & Filippello, P. (2024). School climate and attendance problems: The mediating role of student’s academic and interpersonal competence. Revista INFAD de Psicología. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1), 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, G., Grecu, A. L., & Mori, J. (2024). Error climate and alienation from teachers: A longitudinal analysis in primary school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetland, S., & Hoy, W. (2000). School characteristics and educational outcomes: Toward an organizational model of student achievement in middle schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 36, 703–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 357–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszek, K. (2023). Why it is important to engage students in school activities? Examining the mediation effect of student school engagement on the relationships between student alienation and school burnout. Polish Psychological Bulletin. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țepordei, A.-M., Zancu, A. S., Diaconu-Gherasim, L. R., Crumpei-Tanasă, I., Măirean, C., Sălăvăstru, D., & Labăr, A. V. (2023). Children’s peer relationships, well-being, and academic achievement: The mediating role of academic competence. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1174127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umlauft, S., & Dalbert, C. (2017). Justice experiences and feelings of exclusion. Social Psychology of Education, 20(3), 565–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houtte, M. (2005). Climate or culture? A plea for conceptual clarity in school effectiveness research. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 16(1), 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinciguerra, A., Nanty, I., Guillaumin, C., Rusch, E., Cornu, L., & Courtois, R. (2021). Les déterminants du décrochage dans l’enseignement secondaire: Une revue de littérature. Psychologie Française, 66(1), 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, T. E., Räikkönen, E., Engels, M. C., Vasalampi, K., & Lerkkanen, M.-K. (2021). Student engagement, truancy, and cynicism: A longitudinal study from primary school to upper secondary education. Learning and Individual Differences, 86, 101972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., & Fredricks, J. A. (2014). The reciprocal links between school engagement, youth problem behaviors, and school dropout during adolescence. Child Development, 85(2), 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.-T., & Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 315–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T., & Eccles, J. S. (2013). School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: A longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learning and Instruction, 28, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T., & Holcombe, R. (2010). Adolescents’ perceptions of school environment, engagement, and academic achievement in middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 47(3), 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W., & Jia, F. (2013). A new procedure to test mediation with missing data through nonparametric bootstrapping and multiple imputation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 48(5), 663–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuletu, D. A., Hussein, J. O., & Bareke, M. L. (2024). Exploring school culture and climate: The case of Dilla university community school. Heliyon, 10(11), e31684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengilowski, A., Lee, J., Gaines, R. E., Park, H., Choi, E., & Schallert, D. L. (2023). The collective classroom “we”: The role of students’ sense of belonging on their affective, cognitive, and discourse experiences of online and face-to-face discussions. Linguistics and Education, 73, 101142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

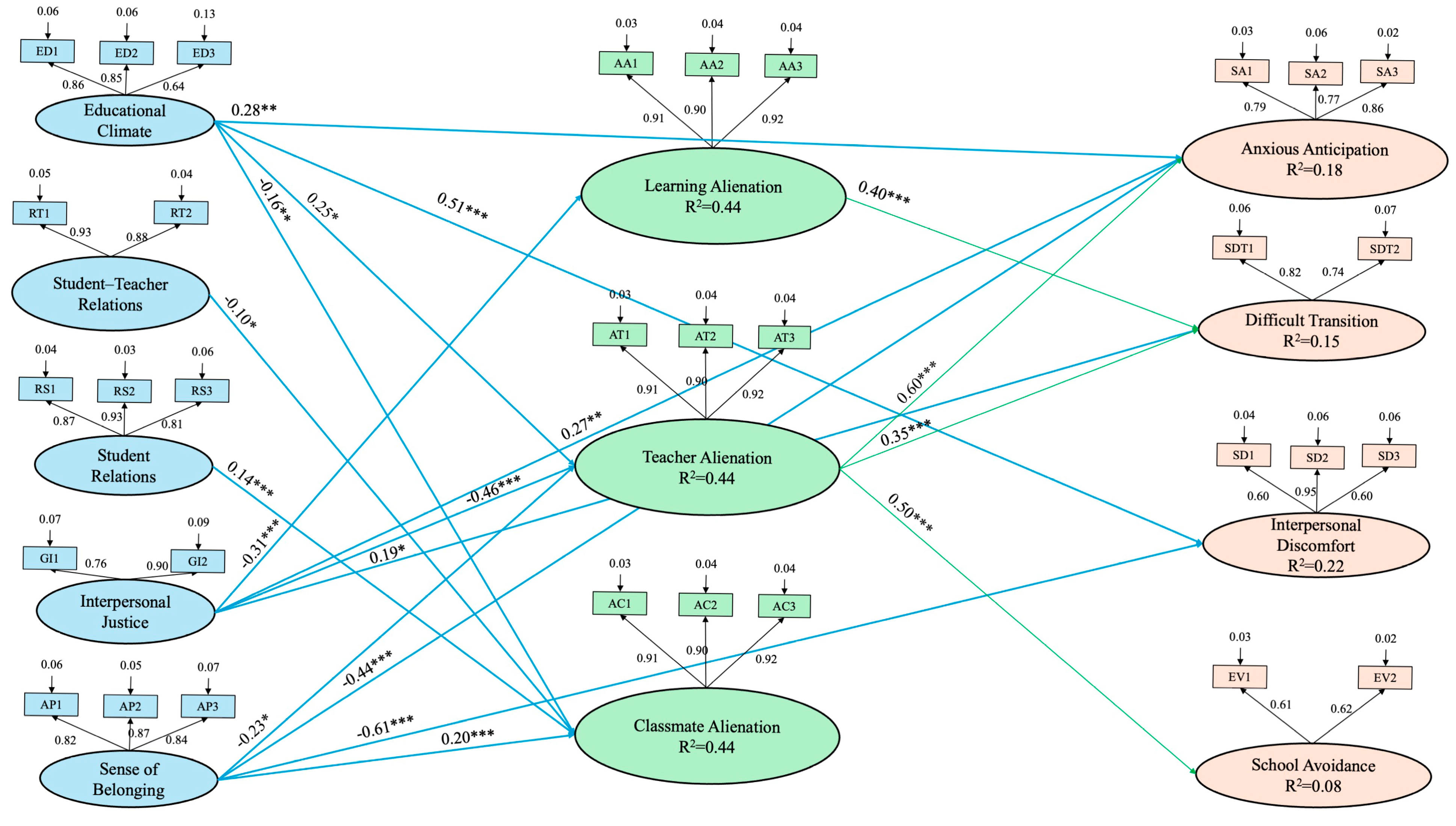

| β | SE | Lower Bound (BC) 95% CI | Upperbound (BC) 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||||

| SAt → SAl | Interpersonal Justice → Learning Alienation | −0.31 | 0.06 | −0.29 | −0.07 | ≤0.001 |

| Educational Climate → Teacher Alienation | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.28 | ≤0.05 | |

| Interpersonal Justice → Teacher Alienation | −0.46 | 0.06 | −0.40 | −0.17 | ≤0.001 | |

| Sense of Belonging → Teacher Alienation | −0.23 | 0.05 | −0.23 | −0.01 | ≤0.05 | |

| Educational Climate → Classmate Alienation | −0.16 | 0.07 | −0.40 | −0.09 | ≤0.01 | |

| Student–Teacher Relations → Classmate Alienation | −0.10 | 0.05 | −0.24 | −0.03 | ≤0.05 | |

| Student Relations → Classmate Alienation | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.33 | ≤0.001 | |

| Sense of Belonging → Classmate Alienation | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.43 | ≤0.001 | |

| SAt → SR | Educational Climate → Anxious Anticipation | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.31 | ≤0.01 |

| Interpersonal Justice → Anxious Anticipation | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.30 | ≤0.01 | |

| Sense of Belonging → Anxious Anticipation | −0.44 | 0.05 | −0.36 | −0.14 | ≤0.001 | |

| Interpersonal Justice → Difficult Transition | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.35 | ≤0.05 | |

| Educational Climate → Interpersonal Discomfort | 0.51 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.42 | ≤0.001 | |

| Sense of Belonging → Interpersonal Discomfort | −0.61 | 0.05 | −0.42 | −0.20 | ≤0.001 | |

| SAl → SR | Learning Alienation → Difficult Transition | 0.40 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.82 | ≤0.001 |

| Teacher Alienation → Anxious Anticipation | 0.60 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.83 | ≤0.001 | |

| Teacher Alienation → Difficult Transition | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.30 | 0.79 | ≤0.001 | |

| Teacher Alienation → School Avoidance | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.42 | ≤0.001 | |

| SAt → SR | Indirect effects via Learning Alienation | |||||

| Interpersonal Justice → Difficult Transition | −0.12 | 0.04 | −0.20 | −0.04 | ≤0.01 | |

| Sense of Belonging → Difficult Transition | −0.14 | 0.04 | −0.16 | −0.01 | ≤0.05 | |

| SAt → SR | Indirect effects via Teacher Alienation | |||||

| Educational Climate → Anxious Anticipation | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.20 | ≤0.05 | |

| Interpersonal Justice → Anxious Anticipation | −0.28 | 0.04 | −0.29 | −0.09 | ≤0.001 | |

| Interpersonal Justice → Difficult Transition | −0.16 | 0.05 | −0.27 | −0.06 | ≤0.01 | |

| Interpersonal Justice → Interpersonal Discomfort | −0.19 | 0.03 | −0.19 | −0.04 | ≤0.01 | |

| Interpersonal Justice → School Avoidance | −0.23 | 0.02 | −0.13 | −0.04 | ≤0.001 | |

| Sense of Belonging → Anxious Anticipation | −0.14 | −04 | −0.16 | −0.01 | ≤0.05 | |

| Sense of Belonging → Interpersonal Discomfort | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.00 | ≤0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sorrenti, L.; Fumia, A.; Caparello, C.; Meduri, C.F.; Filippello, P. The Mediation Role of School Alienation Between Perceptions of the School Atmosphere and School Refusal in Italian Students. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070786

Sorrenti L, Fumia A, Caparello C, Meduri CF, Filippello P. The Mediation Role of School Alienation Between Perceptions of the School Atmosphere and School Refusal in Italian Students. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):786. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070786

Chicago/Turabian StyleSorrenti, Luana, Angelo Fumia, Concettina Caparello, Carmelo Francesco Meduri, and Pina Filippello. 2025. "The Mediation Role of School Alienation Between Perceptions of the School Atmosphere and School Refusal in Italian Students" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070786

APA StyleSorrenti, L., Fumia, A., Caparello, C., Meduri, C. F., & Filippello, P. (2025). The Mediation Role of School Alienation Between Perceptions of the School Atmosphere and School Refusal in Italian Students. Education Sciences, 15(7), 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070786