1. Introduction

Kindergarten curricula in Hong Kong, like their counterparts in other parts of the world, emphasise interdisciplinary study, and all curricular subject areas are integrated into holistic education. Unlike primary and secondary education, kindergarten teachers must regularly plan curricula in all subject areas, including implementing musical activities for children (

Vlah et al., 2019). Music has long played an important role in early childhood classrooms, both formally and informally, to structure daily routines, foster creative expression, and integrate curricular themes (

Gillespie & Glider, 2010). Studies have also highlighted how music is utilised in specific contexts, such as the United States (

Rajan, 2017) or distinct early childhood programmes, such as Reggio Emilia-inspired settings (

Bond, 2015).

To address the evolving needs of the early childhood education (ECE) vocation, pre-service ECE teachers receive an interdisciplinary and generalist teacher education, resulting in insufficient expertise in several subject areas, including music (

Barrett et al., 2018). While some courses integrate music with other art forms (e.g., visual arts, dance, drama) or include music as part of broader arts courses (

W. C. M. Lau & Grieshaber, 2018), many teacher education institutions offer minimal musicianship training for kindergarten teachers (

Carroll & Harris, 2023;

Kim & Kemple, 2011).

Particularly for the population of generalist teachers in early childhood education, research on their teaching confidence and attitudes toward music has gained scholarly attention (

Richards, 1999) across various countries, such as the United States (

Kirby et al., 2023;

Rajan, 2017), Turkey (

Burak, 2019), Cyprus (

Neokleous, 2013), and Australia (

Barrett et al., 2020;

Carroll & Harris, 2023). Teacher education is generally perceived as limited in duration (

Thorn & Brasche, 2015) and insufficient in preparing pre-service teachers with theoretical and pedagogical knowledge (

Filiz & Durnali, 2019), making some teachers feel incapable (

Young, 2001).

Pre-service teachers have left school with strong feelings of inadequacy, believing that good performance skills and musical literacy are necessary to teach music (

Hennessy, 2017), which often affects their confidence and self-efficacy beliefs (

Burak, 2019;

Hatlevik, 2017) and teaching effectiveness (

Klassen et al., 2013). For example,

Xu (

2023) found significant correlations between pre-service teachers’ preparedness to teach various musical genres and their self-efficacy, highlighting the importance of confidence in teaching.

One compelling finding is that many teachers report feeling inadequate in their musical abilities, which negatively impacts their willingness to incorporate singing into their classrooms. For instance,

Swain and Bodkin-Allen (

2014) noted that teachers’ self-reported ‘tone-deafness’—a socially constructed belief—coupled with a fear of negative reactions from peers, greatly influences their confidence in singing. This lack of confidence can create a barrier to integrating music education into preschool environments, reinforcing a cycle of avoidance in singing tasks (

Demorest et al., 2017) and ultimately impacting children’s learning experiences. However, when teachers are self-assured in their singing abilities, they are more inclined to incorporate vocal activities into their teaching, enhancing their role as positive musical models for their students (

Lamont et al., 2012). Therefore, teachers’ confidence in teaching can significantly impact how they support their children’s musical development (

Barrett et al., 2018). This, in turn, influences the effectiveness of various learning and teaching activities in achieving learning objectives (

Chung, 2017).

Research also indicates a link between the ECE teachers’ subject knowledge and the effectiveness of their teaching practices. Although many kindergarten teachers recognise the importance of music for young children’s self-expression, they often demonstrate a limited understanding of the components of an effective music programme (

Scott-Kassner, 1999). Teachers who lack a developed understanding of the importance of music education from their pre-service teacher education may lead students to value music less, hindering their future musical development (

Barrett et al., 2019). Additionally, most pre-service teachers without formal music education have negative attitudes and low self-esteem about their ability to teach music, which can hinder their music teaching, e.g., singing and conducting music activities (

Carroll & Harris, 2023;

Ehrlin & Wallerstedt, 2014).

To address their deficiencies in musical knowledge, teachers often engage in activities that align with their musical strengths (i.e., “natural talents”), which may or may not support the goals of ECE curricula (

Campbell & Scott-Kassner, 2019). They seldom introduce instrumental music activities or projects that involve exploration, improvisation, or sound creation (

Bautista et al., 2018). Negative consequences may also manifest in teachers’ repetitive and teacher-centred classroom practices (

Bautista & Ho, 2021), with a scarcity of creativity-fostering activities (

Cheung, 2017). Research indicates that preschool educators primarily focus on singing songs, often not for musical reasons but to teach children about other learning areas or to introduce new vocabulary (

Garvis, 2012); this lack of musicality and consistency in the curriculum likely deprives children of opportunities to develop their preferences (

Miranda, 2004). These practices fail to sufficiently foster children’s creativity and holistic development (

Bautista et al., 2022;

Campbell & Scott-Kassner, 2019).

While the kindergarten curriculum in Hong Kong emphasises the integration of various subject areas, including music, pre-service and in-service kindergarten teachers often feel ill-equipped to effectively implement musical activities and foster children’s musical development. Additionally, the unique socio-historical and cultural context of Hong Kong has created a complex educational landscape that must balance traditional values with contemporary educational ideals.

2. Cultural Hybridity in Hong Kong’s Early Childhood Education

The historical background of Hong Kong has significantly influenced its educational system. Hong Kong’s historical narrative as a trading centre, a gateway to China, and a meeting point for the East and West has facilitated interactions with European languages and cultures, adding complexity to its educational landscape (

Tang, 2017). The colonial history of Hong Kong, characterised by British colonialism and missionary activities, has intertwined Christianity with Chinese cultural traditions, resulting in a unique cultural hybridity in the region (

Yang, 2024). As a former British colony for over 150 years, this cultural hybridity influences teaching approaches, student–teacher relationships, and the overall educational experience in Hong Kong (

Huang et al., 2018).

Additionally, the common heritage of civilisation, language, literature, and cognitive approaches over millennia has meant that the educational environment in Hong Kong is substantially shaped by traditional Chinese cultural values and Confucian philosophy (

E. Y. M. Chan, 2019;

Hayhoe, 2001). The traditional Confucian values emphasise respect for authority, hierarchy, and the importance of education in maintaining social stability (

J. Wang & Lin, 2019). The influence of Confucianism on education extends to the role of teachers and students in the classroom. According to traditional Chinese values, students are inclined to regard teachers as “experts”, preferring to receive definitive guidance and to engage in learning through passive reception and rote memorisation (

Penfold & van der Veen, 2014). Unlike Western pedagogies that encourage critical thinking, creativity, and self-directed learning (

Tan, 2017), Confucian traditions prioritise group cohesion and deference to authority, often limiting opportunities for students to express individuality or explore creative possibilities (

Niu, 2012;

Pang & Plucker, 2024).

These deeply ingrained cultural norms, reinforced throughout students’ schooling, significantly influence how future educators perceive their roles and responsibilities as teachers (

K. W. Chan, 2004;

E. Y. M. Chan, 2019;

Katz-Buonincontro et al., 2021). Consequently, efforts to promote student-centred pedagogical reforms—particularly in ECE—must contend with the weight of these traditional expectations.

Despite these cultural currents, ECE in Hong Kong has increasingly embraced a child-centred approach. Kindergarten education in Hong Kong, catering to children aged three to six, emphasises a child-centred education policy that nurtures children’s curiosity and interest in learning and exploration, ultimately enabling them to be nurtured into adults who can contribute to society (

Education Bureau, 2016). Children’s interests and demands determine the structure of a child-centred curriculum, and arts education should be a core part of the early childhood curriculum (

Sundberg et al., 2016). Hong Kong incorporates music education as part of arts education in the school curriculum (

Ho, 2013) and positively promotes kindergarten children’s participation in various arts activities related to music, drama, dance, and visual arts (

Curriculum Development Council, 2017). Moreover, the latest edition of the Hong Kong Kindergarten Education Curriculum Guide (in 2017) emphasises music and its value in the same way as other subjects in children’s development. Recent education reforms in Hong Kong have upheld the goal of play-based, child-centred, whole-person learning (

Chung, 2022). ECE in Hong Kong encourages children to actively participate in different musical activities and develop their sensory abilities through movement and singing in response to beats and rhythms, thus stimulating and nurturing their imagination and creativity (

Curriculum Development Council, 2017).

Nonetheless, the coexistence of progressive educational reforms and traditional cultural values presents an ongoing tension in Hong Kong’s early childhood classrooms. While child-centred practices are officially promoted, Confucian-influenced pedagogies continue to shape how teaching and learning are enacted in practice.

4. Method

A total of 467 completed questionnaires from pre-service ECE teachers enrolled in their first year of the higher diploma teacher education programme in Hong Kong were received. This number of participants represented more than half of the total pre-service ECE teachers enrolled at the higher diploma level in the same cohort across the entire Hong Kong region. Upon completing their programme, the participants will be recognised by the Education Bureau in Hong Kong and registered as qualified kindergarten teachers and special childcare workers.

The questionnaire, consisting of 34 questions, explored (1) participants’ demographic information (age, gender, instrumental learning background), (2) their perceived confidence in teaching seven learning areas, (3) their beliefs in the importance of music education, and (4) their perceived confidence in implementing musical activities. Items under categories 2, 3, and 4 were measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 2 = “disagree”; 3 = “neutral”; 4 = “agree”; 5 = “strongly agree”). The items under category 2 were developed based on the “Kindergarten Education Curriculum Guide (2017)” (

the Guide;

Curriculum Development Council, 2017), which offers recommendations and a comprehensive curriculum framework for kindergarten principals, curriculum leaders, and teachers to plan curricula with school-based characteristics (

Curriculum Development Council, 2017). Consistent with the Guide, the music activities listed in the questionnaire encompass a range of music-related activities, including singing, movement, instrument playing, and various forms of performance, appreciation, and creation, regardless of whether the approach is teacher-centred or child-centred.

Items in categories 3 and 4 were developed based on a review of the related literature (

Bautista et al., 2024;

Bautista & Ho, 2021;

W. C. M. Lau & Grieshaber, 2018) and the Guide. The self-confidence scale measures pre-service teachers’ perceived confidence in music instruction, while the belief scale examines their perspectives on the importance of music education for young learners.

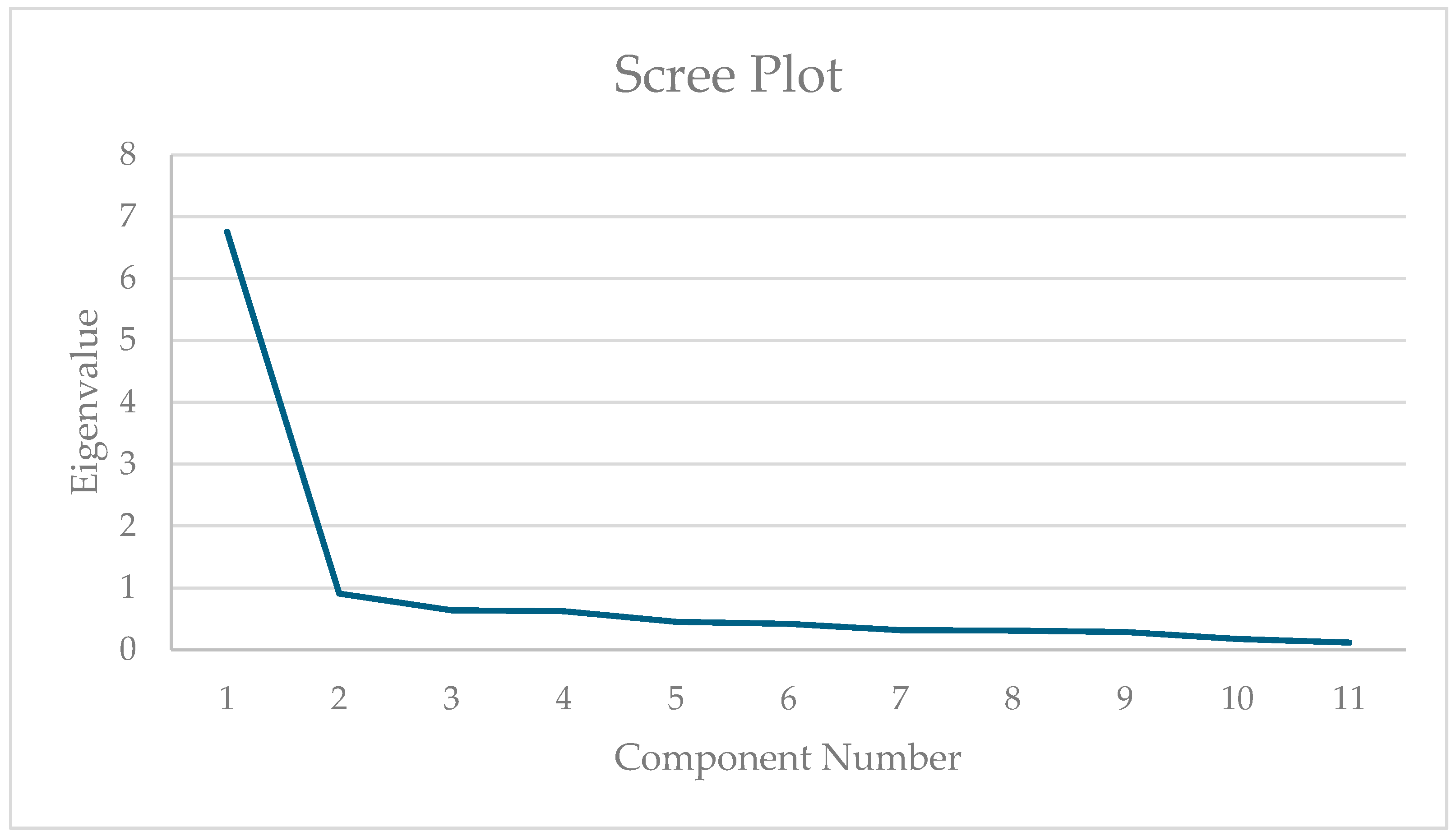

Since pre-service teachers in Hong Kong are familiar with the Guide and implement the kindergarten curriculum based on its recommendations, the questions derived from the Guide could effectively capture teachers’ perceptions within the local context. Expert consultations with two stakeholders in early childhood music education were conducted to inform the initial item construction and to ensure the scales’ validity and reliability. A pilot study involving 10 pre-service teachers was carried out in Spring 2024 to refine the design and wording of the questionnaire, ensuring alignment with the context of ECE in Hong Kong. Subsequently, a factor analysis was performed. The Cronbach α reliability coefficients for the self-confidence in music teaching and belief in music education scales were 0.935 and 0.981, respectively. The respondents were invited to complete the online survey during a class session facilitated by their respective lecturers, resulting in an 86% completion rate, with 467 questionnaires completed. Before completing the questionnaire, informed consent was obtained to ensure participant anonymity and to affirm that their involvement was voluntary. Participants were assured that their responses on the questionnaire or any decision to withdraw from the study would not affect their study in the institution.

6. Discussion

A lack of teacher education in music for generalist teachers inevitably results in their insufficient knowledge and pedagogical skills to conduct music activities, often negatively impacting their confidence in music teaching (

Bautista et al., 2022;

Burak, 2019) and contributing to their weaker beliefs in the importance of children’s music education. Using Hong Kong as a lens, results showed that participants exhibited the lowest confidence in music teaching compared to other learning areas, particularly in activities requiring specialised musical knowledge and creativity, such as instrumental performance and music creation (

Table 2). A significant positive correlation was found between teachers’ perceived confidence and their belief in the importance of music education (

rs(465) = 0.39,

p < 0.001).

First, this study showed that Hong Kong pre-service teachers’ confidence in conducting music activities (

M = 3.01) was the lowest among all learning areas (see

Table 1), which partially mirrors prior research in other cultural contexts (

Topoğlu, 2015). These pre-service teachers expressed lower confidence in carrying out music activities that demand musical skills and creative engagement, such as playing an instrument, creating melodies or rhythms, writing lyrics, and designing movement to music (see

Table 2). Such activities typically involve exploration, improvisation, and sound creation, domains that previous research has identified as areas requiring stronger support in teacher education programmes (

Bautista et al., 2018). This finding is also consistent with

Hennessy’s (

2000) study, which suggests that pre-service teachers often prefer instructional approaches that minimise the need for performance, creativity, or demonstration of musical abilities.

It may be attributed to pre-service teachers’ prior musical experience being associated with their musical perceptions (

Hennessy, 2002), where being musical is often viewed as a higher-order talent tied to music performance ability (

Seddon & Biasutti, 2008). This is further supported by this study’s finding that prior instrumental experience is still perceived as important for music teaching effectiveness (

M = 4.10) (see

Table 3). Pre-service teachers believe one must be an accomplished performer to teach music. Teachers without previous music instrumental learning consider themselves incompetent in different dimensions of music in early childhood music education (

Burak, 2019) and incapable of playing an instrument (

Topoğlu, 2015) or teaching singing, rhythm, and melody (

Hennessy, 2002). Teachers’ low confidence in teaching may make them reluctant to teach music; their perceived musical inadequacy may lead to a causal cycle of their low music teaching expectations (

Hennessy, 2000) and deficient pedagogies (

Burak, 2019), impairing their musical self-development and music teaching motivation.

However, it is worth noting that, compared to the context of the previous decade, music teaching may be less of an expertise subject in today’s context due to the popularity of music education. Although extensive prior research has shown that many teachers lack confidence in music teaching, this study found they only lacked confidence (i.e., mean scores below 3) in certain musical activities (i.e., playing musical instruments or creating melody, rhythm, lyrics, and movement). In

Bautista and Ho’s (

2022) recent study, around half of the 1019 Hong Kong kindergarten teachers who responded had studied how to play a musical instrument, sing, or dance for at least two years. Additionally, regarding credentialism and craving culture endowment in the Chinese context, instrument learning is regarded as a common cultural activity, not a middle-class exclusivity (

Kong, 2023). Instrument learning is rather prevalent, not scarce, in the contemporary Hong Kong context, if not the broader Chinese context. This advanced possession of cultural knowledge may contribute to teachers’ higher confidence levels in music teaching than previous generations’ counterparts.

Moreover, the Chinese pre-service teachers’ deficiency in their creative ability might be attributed to various cultural factors. In the Chinese educational context, there exists a long-standing tradition of teacher-centred pedagogy influenced by Confucian heritage. This emphasis on teacher authority aligns with Confucian principles that underscore the importance of teachers in guiding students’ learning (

Yao et al., 2024). Moreover, research has indicated that Chinese students tend to perceive their creativity as lower in comparison to Western students (

Niu & Sternberg, 2003;

B. Wang & Greenwood, 2013). This perception may be influenced by cultural norms that discourage creativity, such as an emphasis on conformity, practicality, and performance goals over learning goals (

Yue et al., 2011).

Though efforts have been made to address the creativity gap in Chinese education, such as the release of guidelines by the Hong Kong Education Bureau aimed at promoting creativity and curiosity in young children (

Bai et al., 2020), challenges persist in integrating creativity into the education system due to structural impediments and contradictions within the ideology of education in China (

Woronov, 2008). The majority of pre-service teachers have been educated under a tradition of teacher-centred pedagogy, which creates a disparity between their educational backgrounds and the requirement to design and facilitate creative music education in early childhood settings that promote child-centred creativity. This poses potential barriers to the adoption of more progressive, student-centred pedagogies, as their ingrained beliefs and preferences may be at odds with the reformist agendas.

Second, although respondents in this study expressed relatively strong beliefs about the importance of music education in terms of aesthetics, quality of life, and social–emotional benefits (

Table 4), their belief in the importance of music education was significantly correlated to their confidence in music teaching (

rs(465) = 0.39,

p < 0.001). The results corroborate previous studies’ suggestions that low levels of confidence in music teaching may lead to teachers overlooking the importance of children’s music education, attributing music to a secondary learning area compared to other subjects, such as language, literacy, and numeracy (

Bautista et al., 2022). Their insufficient confidence in conducting music teaching may hinder their effectiveness in delivering music activities to meet music education objectives (

Campbell & Scott-Kassner, 2019). Kindergarten teachers who have not developed beliefs in the importance of music education in their pre-service teacher education may cause their students to value music less, impeding their future musical development (

Barrett et al., 2020). Previous research has proven that kindergarten educators have difficulties embedding music in integrated learning activities (

C. Lau & Rao, 2018) and mainly conduct singing activities, not for musical reasons but to teach children about other learning areas or introduce new vocabulary (

Garvis, 2012). Given limited musical knowledge, teachers may rely on their limited musical abilities and engage in activities that only require their “natural talents,” which may or may not contribute to achieving music curricula objectives (

McPherson et al., 2006).

Existing research suggests that kindergarten educators may lack the necessary content knowledge and skills to teach music effectively in their classrooms. For instance,

Russell-Bowie (

2009) found that early year educators in Australia, the United States, Namibia, South Africa, and Ireland lacked musical experience, gave low priority to music in schools, and lacked the resources, time, subject knowledge, and adequate preparation time needed to teach music. Similarly, kindergarten teachers in Hong Kong expressed the need to learn basic music theory and how to design and implement music appreciation activities (

Bautista & Ho, 2021).

Kim and Kemple (

2011) suggested that teachers’ perceived incompetence in basic music reading and playing skills could relate to their confidence and that strengthening their music competence could encourage an enhanced appreciation of music education’s importance for young children. Furthermore, field experiences provide rich opportunities for reflection and enhance strong connections between coursework and practical application (

Blackwell et al., 2022).

The findings from the present study complement these previous studies, indicating that equipping pre-service teachers with teaching skills in areas such as music and movement—where they already demonstrate competence—may serve as a foundation for further professional development. This enhancement of skills may influence their efficacy and beliefs regarding music and movement activities (

Savage et al., 2024). By building on these areas of comfort, teachers can develop greater confidence in tackling more challenging aspects of music instruction. This approach aligns with this study’s findings, as generalist teachers have shown more competence in several areas of music teaching, which can be leveraged to create a more effective music teaching. This, in turn, may improve their overall recognition of the importance of music education and their ability to deliver it effectively.

Although this study indicates a positive relationship between the importance of music education and pre-service teachers’ perceived confidence in music education, it is also crucial to consider that the perceived importance may be heavily influenced by the cultural context of the education system in Hong Kong. This is evident in Hong Kong’s official curriculum guideline (

Curriculum Development Council, 2017), which highlights the arts education’s importance; however, in local kindergartens in Hong Kong, arts and creativity, including music education, are often assigned a secondary role (

Yeung et al., 2022). The predominant focus is on children acquiring factual knowledge and academic skills, rather than nurturing their originality and freedom, which is influenced by the Chinese educational context (

Cheung, 2012). Moreover, the pedagogical approach to arts activities in Hong Kong often prioritises skill acquisition and directs the main goal towards learning in other areas, such as vocabulary acquisition and fine motor development, rather than fostering artistic creativity itself (

Leung, 2020).

Confucianism, which emphasises values of collectivism, conformity, and interdependence (

Li, 2009), manifests in classroom activities. Children’s individual differences and interests are seldom recognised, and children are expected to follow teachers’ instructions rather than explore the arts freely (

Leung, 2020). Additionally, the emphasis on respect for authority and adherence to established norms can create barriers to creative expression, as students may feel constrained by the expectations of conformity within the educational system. However, these practices contradict the importance of creative expression advocated by the official curriculum guidelines in Hong Kong.

7. Conclusions and Implications

While more pre-service teachers in Hong Kong have prior musical experience (

Bautista & Ho, 2022), likely due to the cultural embedding of music as a valued activity, this does not necessarily translate into confidence in teaching music. Respondents demonstrated relatively low confidence in conducting music activities, particularly those requiring creativity or advanced musical skills, such as instrumental performance, music composition, and movement creation (

Table 2). This finding suggests that their prior musical experiences, while beneficial, may not adequately prepare them for the pedagogical demands of music education in early childhood contexts.

This study also found a significant positive correlation between respondents’ confidence in teaching music and their beliefs about the importance of music education (

rs(465) = 0.39,

p < 0.001). This indicates that fostering confidence in music teaching could play a critical role in enhancing teachers’ recognition of music education’s value. However, cultural factors, such as the emphasis on rote learning and teacher-centred pedagogy influenced by Confucian traditions, may limit opportunities for creativity and self-expression, further affecting teachers’ confidence in implementing music activities. This study adds to the growing body of research on the relationships between teacher confidence and beliefs about the value of music education. Its findings underscore the need for tailored, responsive teacher education initiatives that prioritise teacher voice and agency to effectively develop confident and effective music educators (

Kong, 2025).

To address these challenges, teacher education programmes should build upon pre-service teachers’ existing musical knowledge and cultural familiarity with music while providing targeted professional development to enhance their confidence and pedagogical skills. This includes opportunities to explore creative teaching approaches, integrate child-centred music activities, and develop a deeper understanding of the role of music in holistic child development. By addressing these specific gaps, pre-service teachers can be better prepared to implement meaningful and effective music education practices.

While it is crucial to explore how teacher education programmes can cultivate teachers’ abilities to enhance educational creativity in the classroom (

Abramo & Reynolds, 2014), it is equally important to account for the deep-rooted influence of Confucianism in Chinese society. Further research is warranted to examine how the cultural embeddedness of Hong Kong students’ educational experiences shapes their underlying assumptions and pedagogical orientations, particularly in relation to creativity and learner-centred instruction. Amid a simultaneous push for Westernised pedagogy, teacher education programmes must reconceptualise music education to align with the socio-cultural norms of Chinese society. This reconceptualisation should explicitly acknowledge and incorporate the principles and values inherent in Chinese culture.

The quantitative questionnaire employed in this study serves as an exploratory investigation into teachers’ perceptions of their confidence and attitudes toward music education in ECE within the specific context of Hong Kong. This foundation highlights the need for further research to address the gap between teachers’ practices in authentic contexts and the official curriculum in Hong Kong, particularly concerning culturally specific factors. Future studies should consider a qualitative approach to examine teachers’ perceptions of their teaching behaviours as shaped by the cultural context.