Monolingual Early Childhood Educators Teaching Multilingual Children: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Present Review

- (a)

- Provision of a consistent and organized routine;

- (b)

- Provision of a linguistically and culturally responsive environment (e.g., curriculum incorporating the L1, multilevel curriculum, scaffolding through linguistic and non-verbal strategies; home culture reflected in printed materials, books, photos, stories, instructional materials);

- (c)

- Provision of a language- and literacy-rich environment (e.g., activities focused on L1 and L2 acquisition and use, storytelling, shared reading, and use of educational materials);

- (d)

- Provision of participation opportunities (e.g., interaction with adults, peers, play-based activities, large and small group work);

- (e)

- Provision of a collaborative environment (e.g., partnerships with families and other professionals).

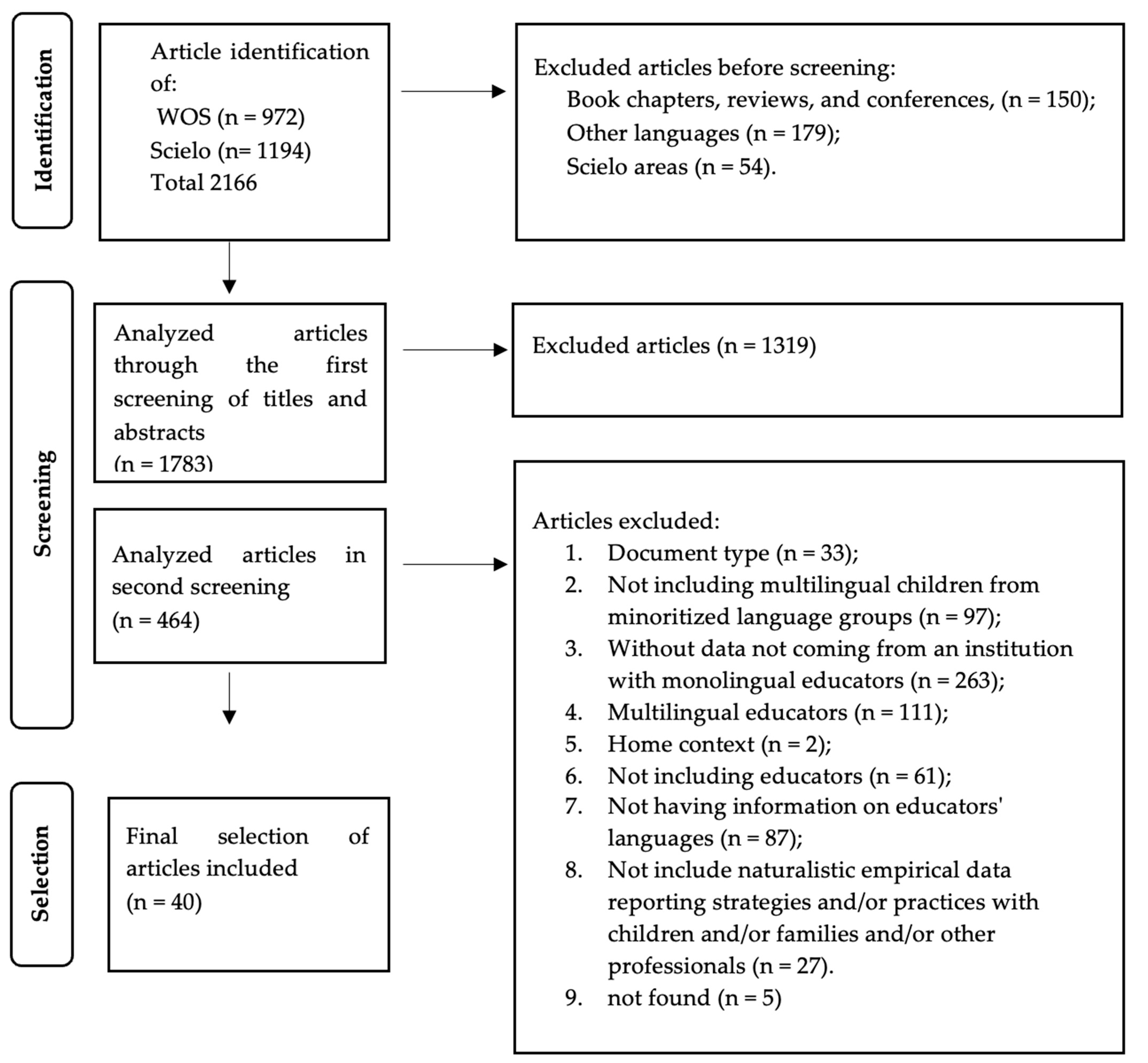

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Questions

2.2. Search Terms

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Article Selection

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of Selected Articles

3.2. Findings for Research Question 1: Characteristics of the Learning Environment

3.2.1. Responsive Environment

3.2.2. Collaboration

3.3. Findings for Research Question 2: Relationship Between Teacher Characteristics and Their Learning Environment Characteristics

3.3.1. Responsiveness to Linguistic–Cultural Diversity

3.3.2. Teacher Preparation

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBE | Intercultural Bilingual Education |

| L1 | First language |

| L2 | Second language |

| LRT | Linguistically Responsive Teaching |

| CRT | Culturally Responsive Teaching |

Appendix A

| Codes | |

|---|---|

| Learning environment characteristics |

|

| Teacher characteristics |

|

References

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, Y. (2025). “Nací Hablando Los dos”: Young emergent bilingual children’s talk about language and identity. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 24(1), 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M. (2019). Playing, talking, co-constructing: Exemplary teaching for young dual language learners across program types. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47(1), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banse, H. W. (2019). Dual language learners and four areas of early childhood learning and development: What do we know and what do we need to learn? Early Child Development and Care, 191(9), 1347–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barac, R., Bialystok, E., Castro, D. C., & Sanchez, M. (2014). The cognitive development of young dual language learners: A critical review. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra-Lubies, R., & Mayo González, S. (2015). Percepciones acerca del rol de las comunidades mapuche en un jardín intercultural bilingüe. Psicoperspectivas. Individuo y Sociedad, 14(3), 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. (2017). The bilingual adaptation: How minds accommodate experience. Psychological Bulletin, 143(3), 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bihler, L.-M., Agache, A., Schneller, K., Willard, J. A., & Leyendecker, B. (2018). Expressive morphological skills of dual language learning and monolingual German children: Exploring links to duration of preschool attendance, classroom quality, and classroom composition. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceño Alcaraz, G. E., Chávez González, A., & Murillo Hernández, M. P. (2018). Un día de clase en un aula intercultural wixárika del norte de Jalisco. Sinéctica, Revista Electrónica de Educación, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, V., Peisner-Feinberg, E., Páez, M., Hammer, C. S., & Knowles, M. (2014). Effects of early education programs and practices on the development and learning of dual language learners: A review of the literature. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 765–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Bustos, J. L. (2019). Estudiantado haitiano en Chile: Aproximaciones a los procesos de integración lingüística en el aula. Revista Educación, 43(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D. C. (2014). The development and early care and education of dual language learners: Examining the state of knowledge. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D. C., Espinosa, L. M., & Páez, M. M. (2011a). Defining and measuring quality in early childhood practices that promote dual language learners’ development and learning. In M. Zaslow, I. Martinez-Beck, K. Tout, & T. Halle (Eds.), Quality measurement in early childhood settings (pp. 257–280). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, D. C., Gillanders, C., Franco, X., Bryant, D. M., Zepeda, M., Willoughby, M. T., & Méndez, L. I. (2017). Early education of dual language learners: An efficacy study of the Nuestros Niños School Readiness professional development program. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 40, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D. C., Páez, M., Dickinson, D., & Frede, E. (2011b). Promoting language and literacy in dual language learners: Research, practice and policy. Child Development Perspectives, 5(1), 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekaite, A., & Evaldsson, A.-C. (2019). Stance and footing in multilingual play: Rescaling practices and heritage language use in a Swedish preschool. Journal of Pragmatics, 144, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cépeda García, N., Castro Burgos, D., & Lamas Basurto, P. (2019). Concepciones de interculturalidad y práctica en aula: Estudio con maestros de comunidades shipibas en el Perú. Educación, 28(54), 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chireac, S. M., & Guerrero-Jiménez, G. R. (2021). Valor del respeto por la lengua y cultura quichua: Concepto del Sumak Kawsay. Alteridad, 16(2), 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Gastélum, G., Tinajero-Villavicencio, M. G., & Carrasco-Altamirano, A. C. (2022). Alfabetización inicial: Decisiones y definiciones pedagógicas de una docente para impulsar la lengua oral y escrita en una institución preescolar indígena. Revista Electrónica Educare, 27(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L. Q., Zhao, J., Shin, J.-Y., Wu, S., Su, J.-H., Burgess-Brigham, R., Gezer, M. U., & Snow, C. (2012). What we know about second language acquisition: A synthesis from four perspectives. Review of Educational Research, 82(1), 5–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, S., & Trawick-Smith, J. (2018). A qualitative study of the play of dual language learners in an English-speaking preschool. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46(6), 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrand, K. M., & Deeg, M. T. (2021). Implementing co-teaching with paraprofessionals to provide pre-Kindergarten students with special rights access to dual language. British Journal of Special Education, 48(3), 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueras-Daniel, A., & Li, Z. (2021). Evidence of support for dual language learners in a study of bilingual staffing patterns using the Classroom Assessment of Supports for Emergent Bilingual Acquisition (CASEBA). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 54, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillmore, L. W., & Snow, C. E. (2018). Language and instruction: Research-based lesson planning and delivery for English learner students. In C. Adger, C. Snow, & D. Christian (Eds.), What teachers need to know about language (2nd ed., pp. 8–51). Multilingual Matters. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.21832/9781788920193-006/html (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Flanagan Bórquez, A. (2021). Estudio sobre las experiencias de docentes chilenos que trabajan con estudiantes inmigrantes en escuelas públicas de la región de Valparaíso, Chile. Perspectiva Educacional, 60(3), 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan-Bórquez, A., Cáceres-Silva, K., & Reyes-Alarcón, J. (2022). Experiencias de maestros en el trabajo con estudiantes inmigrantes: Desafíos para el logro de aulas inclusivas. Revista Colombiana de Educación, 85, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, E. E., Hoy, S. L., Lea, J. L., & García, M. A. (2021). Translanguaging through story: Empowering children to use their full language repertoire. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 21(2), 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, X., Bryant, D. M., Gillanders, C., Castro, D. C., Zepeda, M., & Willoughby, M. T. (2019). Examining linguistic interactions of dual language learners using the Language Interaction Snapshot (LISn). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 48, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O., & Espinosa, C. (2020). Bilingüismo y translanguaging consecuencias para la educación. In L. Martín Rojo, & J. Pujolar (Eds.), Claves para entender el multilingüismo contemporáneo (1st ed., pp. 31–61). Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza. [Google Scholar]

- Garrity, S., Shapiro, A., Longstreth, S., & Bailey, J. (2019). The negotiation of head start teachers’ beliefs in a transborder community. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gelir, I. (2023). Preschool children’s language use in nursery and at home: An investigation of young children’s bilingual development. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 44(5), 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillanders, C. (2007). An English-speaking prekindergarten teacher for young Latino children: Implications of the teacher–child relationship on second language learning. Early Childhood Education Journal, 35(1), 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practice in households, communities, and classrooms. L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Grøver, V., Rydland, V., Gustafsson, J.-E., & Snow, C. E. (2022). Do teacher talk features mediate the effects of shared reading on preschool children’s second-language development? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 61, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J. W., & Lesaux, N. K. (2014). Support for extended discourse in teacher talk with linguistically diverse preschoolers. Early Education and Development, 25(8), 1162–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, C., Sandilos, L., Hammer, C. S., Komaroff, E., Bitetti, D., & López, L. (2023). Teacher language quality in preschool classrooms: Examining associations with DLLs’ oral language skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 63, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, S., & Alvarado, S. (2021). Two dual language preschool teachers’ critical consciousness of their roles as language policy makers. Bilingual Research Journal, 44(4), 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A. L., Dahbi, M., Surrain, S., Rowe, M. L., & Luk, G. (2023). Music uses in preschool classrooms in the U.S.: A multiple-methods study. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(3), 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langeloo, A., Mascareño Lara, M., Deunk, M. I., Klitzing, N. F., & Strijbos, J.-W. (2019). A systematic review of teacher–child interactions with multilingual young children. Review of Educational Research, 89(4), 536–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A. L., Cycyk, L. M., Carta, J. J., Hammer, C. S., Baralt, M., Uchikoshi, Y., An, Z. G., & Wood, C. (2020). A systematic review of language-focused interventions for young children from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 50, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limlingan, M. C., McWayne, C., & Hassairi, N. (2022). Habla Conmigo: Teachers’ Spanish talk and Latine dual language learners’ school readiness skills. Early Education and Development, 33(4), 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limlingan, M. C., & McWayne, C. M. (2023). More than words: A qualitative study on the links between preschool teachers’ classroom practices and their language ideologies about dual language learners. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(5), 981–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loncón, E., Gaínza, A., Hirmas, N., & Mellado, D. (2023). Filosofía del azmapu. In Colonialismo cultural y ontología indígena en comunidades pewenche de Alto Biobío (Primera ed., pp. 35–38). LOM Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- López, L. M., & Páez, M. M. (2021). Effective classroom practices for working with DLLs. In Teaching dual language learners: What early childhood educators need to know (pp. 134–156). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2013). Preparing linguistically responsive teachers: Laying the foundation in preservice teacher education. Theory Into Practice, 52(2), 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, T., Villegas, A. M., & Freedson-Gonzalez, M. (2008). Linguistically responsive teacher education: Preparing classroom teachers to teach English language learners. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, O., Lundqvist, U., Åkerblom, A., & Risenfors, S. (2023). ‘Can you teach me a little Urdu?’ Educators navigating linguistic diversity in pedagogic practice in Swedish preschools. Global Studies of Childhood, 13(3), 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, L., & Young, A. (2018). Parents in the playground, headscarves in the school and an inspector taken hostage: Exercising agency and challenging dominant deficit discourses in a multilingual pre-school in France. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 31(3), 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, L., & Young, A. S. (2017). Engaging with emergent bilinguals and their families in the pre-primary classroom to foster well-being, learning and inclusion. Language and Intercultural Communication, 17(4), 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, J. B., Mancilla-Martinez, J., Flores, I., & Buckley, L. (2021). Translanguaging to support emergent bilingual students in English dominant preschools: An explanatory sequential mixed-method study. Bilingual Research Journal, 44(2), 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2017). Promoting the educational success of children and youth learning English: Promising futures. National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ovati, T. S. R., Rydland, V., Grøver, V., & Lekhal, R. (2024). Teacher perceptions of parent collaboration in multi-ethnic ECEC settings. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1340295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, J., Genesee, F., & Crago, M. B. (2021). Chapter 3: The language-neurocognition conection. In Dual language development & disorders: A handbook on bilingualism and second language learning (3rd ed., pp. 57–62). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Peleman, B., Van Der Wildt, A., & Vandenbroeck, M. (2022). Home language use with children, dialogue with multilingual parents and professional development in ECEC. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 61, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plascencia González, M., & Núñez Patiño, K. (2022). Perspectivas de la educación formal con infancias ante el COVID-19: El contexto de chiapas. Cadernos CEDES, 42(118), 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzo, M. I., & Parucci, M. P. (2017). La educación intercultural bilingüe en la localidad de La Dsperanza, provincia de Jujuy, Argentina. Un estudio de caso sobre su impacto en el rol docente. Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales—Universidad Nacional de Jujuy, 52, 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Puskás, T. (2017). Picking up the threads. Languaging in a Swedish mainstream preschool. Early Years, 37(3), 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puskás, T., & Björk-Willén, P. (2017). Dilemmatic aspects of language policies in a trilingual preschool group. Multilingua, 36(4), 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, R., Huang, B. H., Palomin, A., & McCarty, L. (2021). Teachers and language outcomes of young bilinguals: A scoping review. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52(2), 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, R., López, L. M., & Ferron, J. (2019). Teacher characteristics that play a role in the language, literacy and math development of dual language learners. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47(1), 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, B., Atkins-Burnett, S., Sandilos, L., Scheffner Hammer, C., Lopez, L., & Blair, C. (2018). Variations in classroom language environments of preschool children who are low income and linguistically diverse. Early Education and Development, 29(3), 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, B. E., Manz, P. H., & Martin, K. A. (2017). Supporting preschool dual language learners: Parents’ and teachers’ beliefs about language development and collaboration. Early Child Development and Care, 187(3–4), 707–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembiante, S. F., Yeomans-Maldonado, G., Johanson, M., & Justice, L. (2023). How the amount of teacher spanish use interacts with classroom quality to support English/Spanish DLLs’ vocabulary. Early Education and Development, 34(2), 506–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, T. D., Moran, M. K., Petersen, D. B., Thompson, M. S., & Restrepo, M. A. (2024). A design-based implementation study of a preschool Spanish/English multi-tiered language curriculum/Estudio de implementación basada en el diseño de un currículum preescolar multinivel inglés/español. Journal for the Study of Education and Development: Infancia y Aprendizaje, 47(1), 138–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabors, P. O. (2008). Using the curriculum to facilitate second-language and-literacy learning. In P. Tabors (Ed.), One child, two languages: A guide for early childhood educators of children learning English as a second language (2nd ed., pp. 105–124). Paul H. Brookes Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L. (1994). The Cleveland project: A study of bilingual children in a nursery school. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 15(2–3), 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trawick-Smith, J., DeLapp, J., Bourdon, A., Flanagan, K., & Godina, F. (2023). The influence of teachers, peers, and play materials on dual language learners’ play interactions in preschool. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(5), 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M., & García, G. E. (2000). Who’s the boss? How communicative competence is defined in a multilingual preschool classroom. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 31(2), 230–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubino, F. (2004). Del interculturalismo funcional al interculturalismo crítico. In M. Samaniego, & C. G. Garbarini (Eds.), Rostros y fronteras de la identidad. Universidad Católica de Temuco. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2016). If you don’t understand, how can you learn? UNESCO GEMR. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2020). Informe de Seguimiento de la Educación en el Mundo 2020: Inclusión y educación: Todos y todas sin excepción. UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C. E. (2010). Interculturalidad crítica y educación intercultural. In J. Viaña Uzieda, L. Tapia Mealla, & C. E. Walsh (Eds.), Construyendo interculturalidad crítica (pp. 77–79). Instituto Internacional de Integración Convenio Andrés Bello. [Google Scholar]

- Washington-Nortey, P.-M., Zhang, F., Xu, Y., Ruiz, A. B., Chen, C.-C., & Spence, C. (2022). The impact of peer interactions on language development among preschool English language learners: A systematic review. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(1), 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsler, A., Burchinal, M. R., Tien, H.-C., Peisner-Feinberg, E., Espinosa, L., Castro, D. C., LaForett, D. R., Kim, Y. K., & De Feyter, J. (2014). Early development among dual language learners: The roles of language use at home, maternal immigration, country of origin, and socio-demographic variables. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettl, E. (2023). Forbidding and valuing home languages—Divergent practices and policies in a German nursery school. International Journal of Multilingualism, 20(4), 1353–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z., Degotardi, S., & Djonov, E. (2021). Supporting multilingual development in early childhood education: A scoping review. International Journal of Educational Research, 110, 101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Country | Early Education Level | Bilingual Program Type | Children Age | Children Languages | Teachers nº | Teacher Language | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Baker, 2019) | USA | Early education | none | 3–6 years | English, Spanish +10 | Not specified | English, Spanish +10 | qualitative: multiple case study |

| (Becerra-Lubies & Mayo González, 2015) | Chile | Early education | IBE | 4–5 years | Spanish, Mapudungún | 2 | Spanish | qualitative: case study |

| (Bihler et al., 2018) | Germany | Early education | none | 2.5–3.9 years | German, Turkish, Russian, Polish, Arabic, Albanese | 135 | German | quantitative: correlational |

| (Briceño et al., 2018) | México | Primary school | IBE | 4–12 years | Spanish, Wixarika | 1 | Spanish | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (Campos-Bustos, 2019) | Chile | Primary school | none | 4–5 years | Haitian Creole, Spanish, French, English | 19 | Spanish | quantitative: descriptive. qualitative: interviews |

| (Cekaite & Evaldsson, 2019) | Sweden | Early education | none | 3–6 years | Kurdish, Croatian | 1 | Sweden | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (Cépeda García et al., 2019) | Perú | Primary school | IBE | 3–12 years | Spanish, Shipibo | 6 | Spanish | qualitative: interviews |

| (Chireac & Guerrero-Jiménez, 2021) | Ecuador | Primary rural school | IBE | 3–15 years | Spanish, Quechua | Not specified | Spanish | qualitative: interviews |

| (Delgado-Gastélum et al., 2022) | México | Early education | IBE | 5 years | Spanish, Tsotsil | 1 | Spanish | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (Dominguez & Trawick-Smith, 2018) | USA | Early education | none | 3.7–4.5 years | Chinese, Spanish | 3 | English | qualitative: case study |

| (Farrand & Deeg, 2021) | USA | Special education school | dual | 3–5 years | Spanish, English, Arabic | 1 | English | qualitative: case study |

| (Flanagan Bórquez, 2021) | Chile | Primary school | none | 4–5 years | Chinese, Spanish, Haitian Creole | 1 | Spanish | qualitative: interviews |

| (Flanagan-Bórquez et al., 2022) | Chile | Primary school | none | 4–5 years | Spanish, Chinese, Russian, Haitian Creole | 10 | Spanish | qualitative: phenomenological |

| (Flynn et al., 2021) | USA | Early education | none | 4 years | English, Spanish, Arabic, Somali, Creole, Russian | 1 | English | qualitative: observational |

| (Garrity et al., 2019) | USA | Early education | none | - | Spanish, English | 17 | English, Spanish | quantitative: correlational |

| (Gelir, 2023) | Turkey | Early education | none | 3–6 years | Kurdish | 1 | Turkish | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (Gillanders, 2007) | USA | Primary school | none | 4 years | Spanish | 1 | English | qualitative: case study |

| (Jacoby & Lesaux, 2014) | USA | Early education | none | 2.9–6 years | Spanish, English | 3 | English | quantitative: correlational |

| (Kilinc & Alvarado, 2021) | USA | Primary school | dual | 4–5 years | Spanish, English, Korean, Arabic, Nepali | 1 | English | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (Kirby et al., 2023) | USA | Early education | none | 1–5 years | - | 102 | English | multiple methods |

| (Langeloo et al., 2019) | Netherlands | Early education | none | 5–6 years | Turkish, Dutch, English, +5 | 19 | Dutch | qualitative: observational |

| (Limlingan & McWayne, 2023) | USA | Early education | none | - | Spanish, English | 7 | English | qualitative: phenomenological |

| (Limlingan et al., 2022) | USA | Early education | none | 4 years | Spanish, English | 5 | English | quantitative: correlational |

| (Lundberg et al., 2023) | Sweden | Early education | none | 3–5 years | Arabic, French, English, +10 | 2 | Sweden | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (Mary & Young, 2017) | France | Primary school | none | 3–4 years | French, Turkish, Serbian, Arabic, Albanese | 1 | French | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (Mary & Young, 2018) | France | Primary school | none | 3–4 years | French, Turkish, Serbian, Arabian, Arabic | 1 | French | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (McClain et al., 2021) | USA | Early education | immersion | 3–5 years | Spanish, English | 2 | English | Mixed |

| (Ovati et al., 2024) | Norway | Early education | none | - | - | 167 | Norwegian | quantitative: correlational |

| (Peleman et al., 2022) | Belgium | Early education | none | - | - | 242 | Dutch | quantitative: correlational |

| (Plascencia González & Núñez Patiño, 2022) | México | Primary school | none | 3–6 years | Spanish, native languages | Not specified | Spanish | qualitative: interviews |

| (Pozzo & Parucci, 2017) | Argentina | Primary school | IBE | 4–5 years | Guaraní, Spanish | 8 | Spanish | qualitative: interviews |

| (Puskás & Björk-Willén, 2017) | Sweden | Early education | none | 3–5 years | Swedish, Romani, Arabic, Polish, Greek, Vietnamese | 2 | Swedish | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (Puskás, 2017) | Sweden | Early education | none | 3–5 years | Swedish, Arabic, Romani, Greek | 1 | Swedish | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (Ramírez et al., 2019) | EEUU | Early education | none | 3–5 years | Spanish, English | Not specified | English | quantitative: cross-sectional, longitudinal |

| (Sawyer et al., 2017) | EEUU | Early education | none | 3.2–5.5 years | Spanish, English | 3 | English | qualitative: consensual |

| (Sembiante et al., 2023) | USA | Early education | none | 4 years | Spanish, English | Not specified | English, Spanish | quantitative: correlational |

| (Thompson, 1994) | UK | Early education | none | 3 years | Mirpuri, English | Not specified | English | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (Trawick-Smith et al., 2023) | USA | Early education | none | 3–5 years | Spanish, English | 2 | English | quantitative: correlational |

| (Tsai & García, 2000) | EEUU | Early education | none | 3–4 years | Chinese, Spanish, Polish, Urdu | 1 | English | qualitative: ethnographic |

| (Zettl, 2023) | Germany | Early education | none | 2–7 years | German, Turkish, Albanese, Bulgarian, Dutch | 1 | German | qualitative: ethnographic |

| Category | Strategies and Practices | Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of the learning environment; responsive environment | Linguistics:

| (Campos-Bustos, 2019; Cekaite & Evaldsson, 2019; Farrand & Deeg, 2021; Gillanders, 2007; Mary & Young, 2017, 2018; McClain et al., 2021; Limlingan & McWayne, 2023; Lundberg et al., 2023; Sembiante et al., 2023; Tsai & García, 2000) |

Linguistics:

| (Baker, 2019; Gelir, 2023; Gillanders, 2007; Jacoby & Lesaux, 2014; Kirby et al., 2023) | |

Linguistics:

| (Baker, 2019; Flynn et al., 2021; Gillanders, 2007; Kirby et al., 2023; Limlingan & McWayne, 2023; Trawick-Smith et al., 2023; Zettl, 2023) | |

Cultural:

| (Becerra-Lubies & Mayo González, 2015; Cépeda García et al., 2019; Chireac & Guerrero-Jiménez, 2021) | |

| Characteristics of the learning environment; collaboration strategies |

| (Cekaite & Evaldsson, 2019; Farrand & Deeg, 2021; Puskás & Björk-Willén, 2017; Trawick-Smith et al., 2023; Zettl, 2023; Becerra-Lubies & Mayo González, 2015; Campos-Bustos, 2019) |

| (Baker, 2019; Mary & Young, 2017, 2018; Chireac & Guerrero-Jiménez, 2021; Flanagan-Bórquez et al., 2022) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaramillo-López, C.; Mendive, S.; Castro, D.C. Monolingual Early Childhood Educators Teaching Multilingual Children: A Scoping Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070869

Jaramillo-López C, Mendive S, Castro DC. Monolingual Early Childhood Educators Teaching Multilingual Children: A Scoping Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):869. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070869

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaramillo-López, Camila, Susana Mendive, and Dina C. Castro. 2025. "Monolingual Early Childhood Educators Teaching Multilingual Children: A Scoping Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070869

APA StyleJaramillo-López, C., Mendive, S., & Castro, D. C. (2025). Monolingual Early Childhood Educators Teaching Multilingual Children: A Scoping Review. Education Sciences, 15(7), 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070869