Exploring Multilingualism to Inform Linguistically and Culturally Responsive English Language Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Linguistically and Culturally Responsive Approaches to Research and Practice in ELE

3. Methodology

3.1. The Case Study Approach

3.1.1. The Macro-Level: Middle Schools in Austria

3.1.2. The Meso-Level: Case Middle School (Case-MS)

3.1.3. The Micro-Level: The Embedded Cases of Liona and Ronald

3.2. Data Collection

3.2.1. Observations

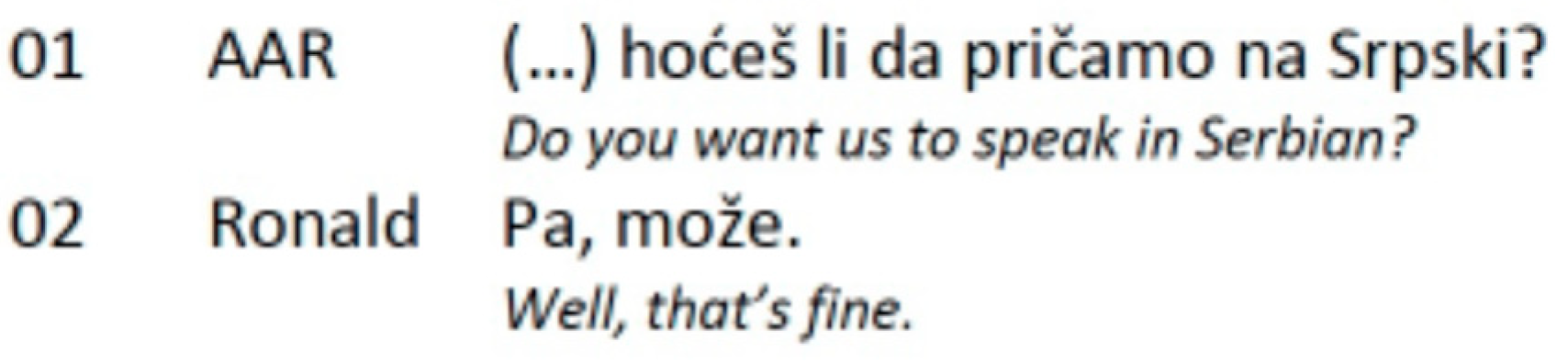

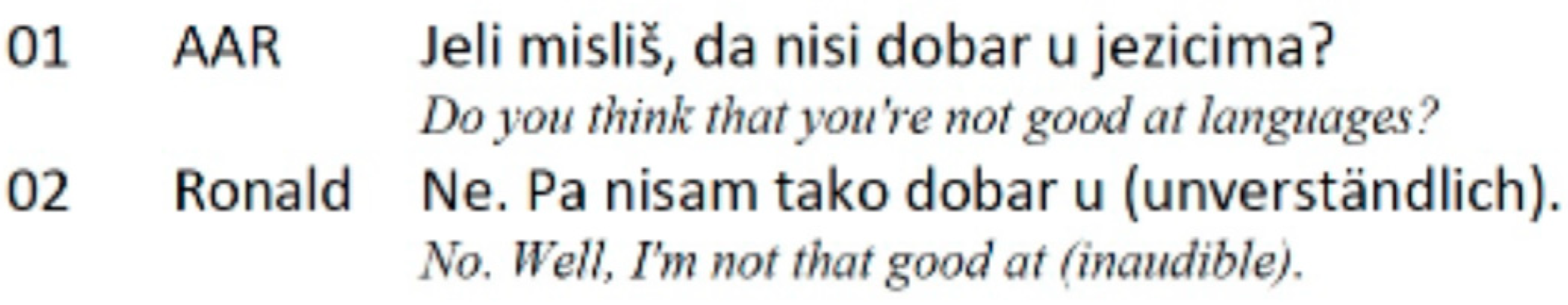

3.2.2. Student Interviews

3.2.3. Ethnographic Fieldwork

3.2.4. Student Work

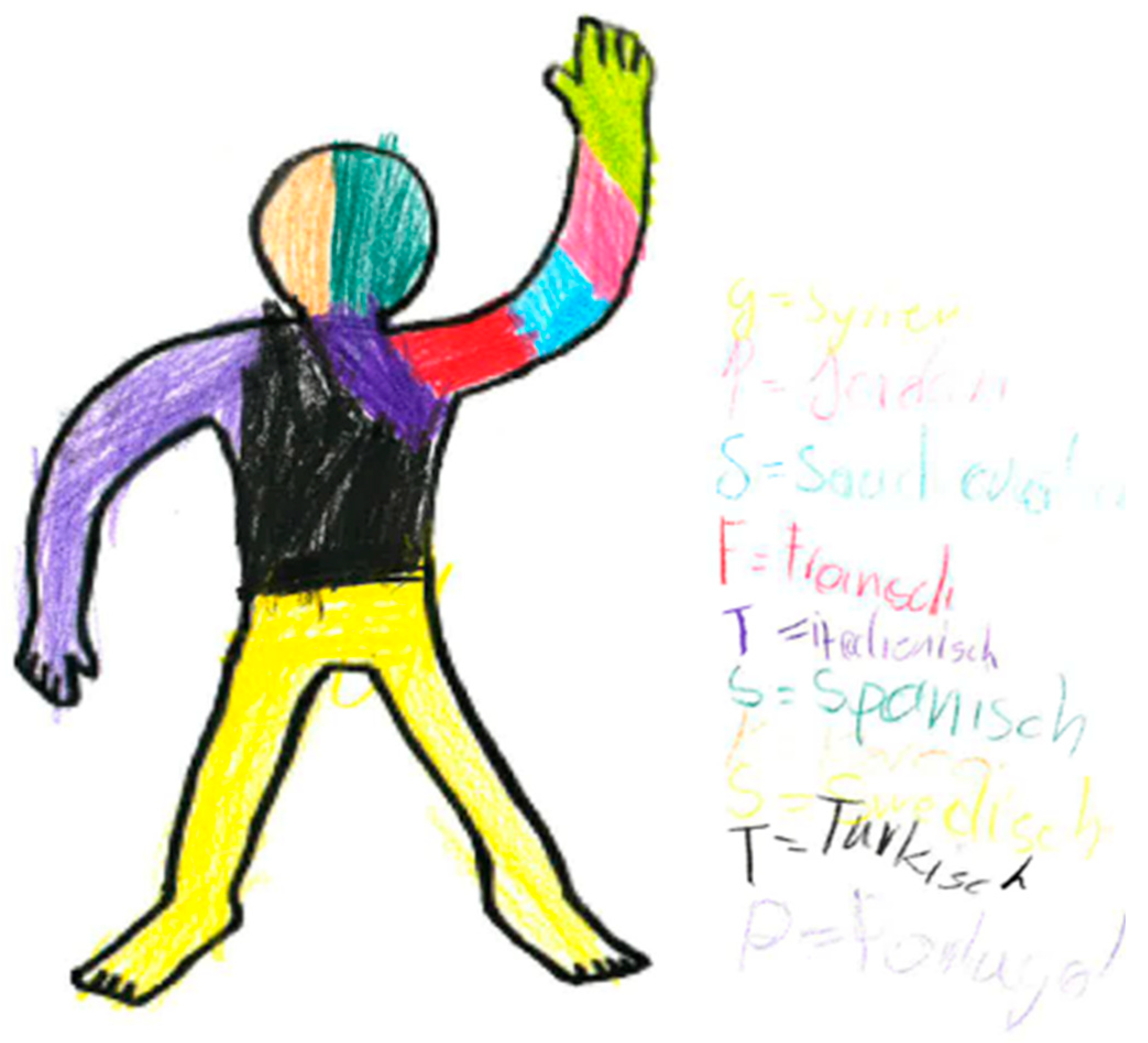

3.2.5. Students’ Language Portraits

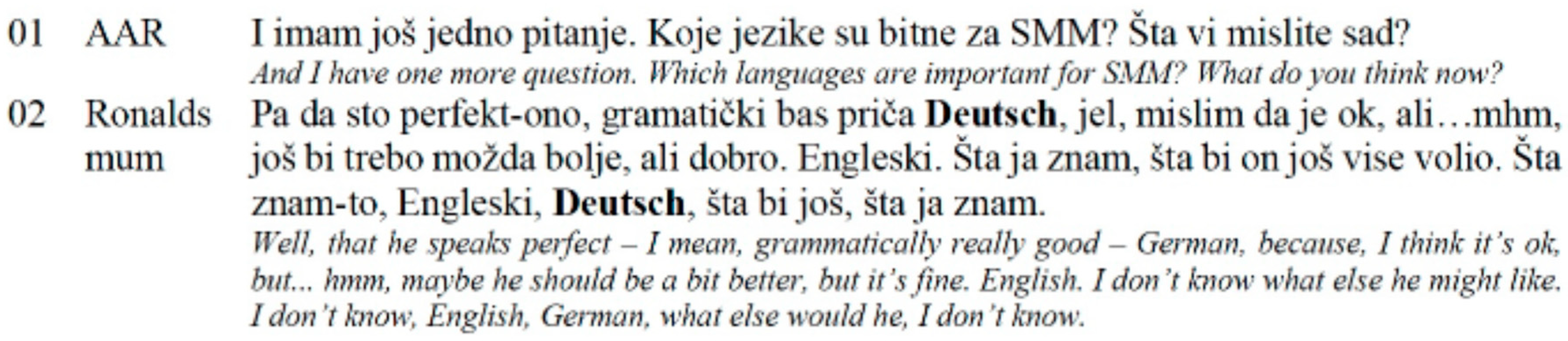

3.2.6. Parent Interviews

3.3. Ethical Considerations

3.4. Data Processing

3.5. Data Analyses

4. Findings

4.1. Liona: Educational and Linguistic Trajectory

4.1.1. Background

4.1.2. Family and Social Networks

4.1.3. Schooling Experience

4.1.4. Linguistic Practices and Identity

4.2. Ronald: Educational and Linguistic Trajectory

4.2.1. Background

4.2.2. Family and Social Networks

4.2.3. Schooling Experience

4.2.4. Linguistic Practices and Identity

“Kurz vor Pause an der Tür: ‘Die Türken und die Serben raus!’ [Shortly before the break, at the door: ‘The Turks and the Serbs outside!’] Then sings something in Turkish. Second time that he makes origin a subject of ‘decision’. Seems to be important for him”(observations, EJE complemented by MW, 17 March 2023)

5. Discussion: Navigating Complex Linguistic and Cultural Identities in the Education Sector

5.1. The Role of School in Shaping Multilingual Identity

5.2. Belongings and the Pressure of Categorization

5.3. Spracherleben and Language Ideologies

5.4. From Identity to Pedagogy: Implications for LCRPs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | An FWF funded project (Project V-975): https://udele2023.univie.ac.at/ (accessed on 24 May 2025). |

| 2 | We use the term Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (BCS) (BKS in German) to refer to the mutually intelligible South Slavic varieties commonly spoken in the region. While students may self-identify with one specific variety, we refer to the language as BCS to acknowledge the linguistic proximity and shared features of varieties, while recognizing the socio-political weight of naming practices. Ronald and his mother, however, refer to the language(s) as Serbian. |

| 3 | The student names used in this article are pseudonyms, which have been selected by the students themselves. We have chosen to refer to them this way, instead of with the code used in our database to improve readability and narrative flow in this article. |

| 4 | The term “Romani” refers to the diverse Indo-Aryan languages spoken by Romani communities across Europe and beyond. As these varieties are often collectively referred to as “Romani” in academic and policy contexts, we use that term in this text, though speakers themselves may use different terms, such as “Romanes,” depending on regional and cultural contexts (Halwachs, 2003). The language includes multiple dialects with significant variation in vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation, shaped by the communities’ histories of migration and contact with other languages. While Romani is recognized as a minority language in several European countries, it often remains marginalized in formal education systems. |

| 5 | The term “Zigeunerisch” is an outdated and offensive label once used for the Romani language, associated with discrimination against Romani communities (New et al., 2017). However, we have observed that some students use this term when referring to their own linguistic repertoires. |

References

- Akkan, B., & Buğra, A. (2021). Education and “categorical inequalities’’: Manifestation of segregation in six country contexts in Europe. Social Inclusion, 9(3), 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackledge, A., & Creese, A. (2010). Multilingualism: A critical perspective. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Blackledge, A., & Creese, A. (2023). Essays in linguistic ethnography: Ethics, aesthetics, encounters. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Blommaert, J., & Jie, D. (2010). Ethnographic fieldwork: A beginner’s guide. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Blommaert, J., & Varis, P. (2015). Enoughness, accent and light communities: Essays on contemporary identities (Tilburg papers in culture studies, No. 139). Available online: https://research.tilburguniversity.edu/en/publications/enoughness-accent-and-light-communities-essays-on-contemporary-id (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Association for Applied Linguistics (BAAL). (2021). Recommendations on good practice in applied linguistics (4th ed.). British Association for Applied Linguistics. Available online: https://www.baal.org.uk/who-we-are/resources/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1981). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, R. (2004). Ethnicity without groups. Ethnicity, Nationalism, and Minority Rights, 43(2), 50–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, B. (2012). The linguistic repertoire revisited. Applied Linguistics, 33(5), 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, B. (2015). Linguistic repertoire and Spracherleben, the lived experience of language. Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies, 145, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, B. (2018). The language portrait in multilingualism research: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Working Papers in Urban Language and Literacies, 236, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2025). Pedagogical translanguaging: A substantive approach. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 15(1), 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. (2001). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society (2nd ed.). California Association for Bilingual Education. [Google Scholar]

- Darvin, R., & Norton, B. (2014). Social class, identity, and migrant students. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 13(2), 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, A. (2020). Why do so many children who hear two languages speak just a single language? Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 25, 1. Available online: https://zif.tujournals.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/article/id/3221/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (5th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, J., & Günther-van Der Meij, M. (2020). ‘We learn together’—Translanguaging within a holistic approach towards multilingualism in education. In J. A. Panagiotopoulou, L. Rosen, & J. Strzykala (Eds.), Inclusion, education and translanguaging (pp. 125–144). Springer Fachmedien. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, P. A. (2015). Transnationalism, multilingualism, and identity. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erling, E. J., Brummer, M., & Foltz, A. (2022a). Pockets of possibility: Students of English in diverse, multilingual secondary schools in Austria. Applied Linguistics, 44(1), 72–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erling, E. J., & Foltz, A. (2024). English language learning in Austria: The role of teachers’ beliefs about their students’ social backgrounds. In G. Keplinger, A. Schurz, & E. Kreuthner (Eds.), New pathways in teaching English (pp. 79–106). Trauner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Erling, E. J., Foltz, A., Siwik, F., & Brummer, M. (2022b). Teaching English to linguistically diverse students from migration backgrounds: From deficit perspectives to pockets of possibility. Languages, 7(3), 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erling, E. J., Foltz, A., & Wiener, M. (2021). Differences in English teachers’ beliefs and practices and inequity in Austrian English language education: Could plurilingual pedagogies help close the gap? The International Journal of Multilingualism, 18(4), 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erling, E. J., & Weidl, M. (2025a). Enhancing English language teacher education in linguistically diverse urban middle schools: Navigating possibilities within constraints. Journal of Second Language Teacher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Erling, E. J., & Weidl, M. (2025b). Enhancing the research-praxis nexus: Critical moments from a linguistically diverse English language teacher education project. System. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Guitart, M. (2016). Funds of identity: Connecting meaningful learning experiences in and out of school (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expertenrat für Integration. (2019). Integrationsbericht: Integration in österreich—Zahlen, entwicklungen, schwerpunkte. Available online: https://www.bmeia.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Zentrale/Integration/Integrationsbericht_2019/Pressemappe.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Fisher, L., Evans, M., Forbes, K., Gayton, A., & Liu, Y. (2020). Participative multilingual identity construction in the languages classroom: A multi-theoretical conceptualisation. International Journal of Multilingualism, 17(4), 448–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, K., Evans, M., Fisher, L., Gayton, A., Liu, Y., & Rutgers, D. (2021). Developing a multilingual identity in the languages classroom: The influence of an identity-based pedagogical intervention. The Language Learning Journal, 49(4), 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, K., Evans, M., Fisher, L., Gayton, A., Liu, Y., & Rutgers, D. (2024). ‘I feel like I have a superpower’: A qualitative study of adolescents’ experiences of multilingual identity development during an identity-based pedagogical intervention. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O. (2009). Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st century. In Social justice through multilingual education (pp. 140–158). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O., & Kleyn, T. (Eds.). (2016). Translanguaging with multilingual students: Learning from classroom moments. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O., Zakharia, Z., & Otcu-Grillman, B. (2012). Bilingual community education and multilingualism: Beyond heritage languages in a global city (p. 343). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2006). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, ommunities, and classrooms (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R. R. (2022). Translanguaging pedagogy as methodology: Leveraging the linguistic and cultural repertoires of researchers and participants to mutually construct meaning and build rapport. In P. Holmes, J. Reynolds, & S. Ganassin (Eds.), The politics of researching multilingually (pp. 267–286). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granström, M., Kikas, E., & Eisenschmidt, E. (2023). Classroom observations: How do teachers teach learning strategies? Frontiers in Education, 8, 1119519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwachs, D. W. (2003). The changing status of Romani in Europe. In G. Hogan-Brun, & S. Wolff (Eds.), Minority languages in Europe (pp. 192–207). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. (2013). Doing discourse analysis in sociolinguistics. In J. Holmes, & K. Hazen (Eds.), GMLZ—Guides to research methods in language and linguistics: Research methods in sociolinguistics: A practical guide (pp. 177–193). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hölscher, S. I. E., Schachner, M. K., Juang, L. P., & Altoè, G. (2024). Promoting adolescents’ heritage cultural identity development: Exploring the role of autonomy and relatedness satisfaction in school-based interventions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53(11), 2460–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultgren, A. K., Erling, E. J., & Chowdhury, Q. H. (2016). Ethics in language and identity research. In S. Preece (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of language and identity (pp. 257–272). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jalil, C. R. A. (2023). The application of culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy in english speaking classrooms—A case study. International Journal of English Language Teaching, 11(2), 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J. E. (2022). ‘Every line is a lie’: The geographical and cognitive mapping of multilingualism and identity. In L. Fisher, & W. Ayres-Bennett (Eds.), Multilingualism and identity: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 21–42). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Core. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaja, P., & Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2025). Introduction: Being multilingual and living multilingually—Advancing a social justice agenda in applied language studies. In P. Kalaja, & S. Melo-Pfeifer (Eds.), Visualising language students and teachers as multilinguals (pp. 1–24). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatsareas, P. (2022). Semi-structured interviews. In R. Kircher, & L. Zipp (Eds.), Research methods in language attitudes (pp. 99–113). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Core. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B. (2023). Connecting the racial to the spatial; migration, identity and educational settings as a third space. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 75(1), 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. J. Y., & Weng, Z. (2022). A systematic review on pedagogical translanguaging in TESOL. Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language Journal–TESL-EJ, 26(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K. A., Fogle, L., & Logan-Terry, A. (2008). Family language policy. Language and Linguistics Compass, 2(5), 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleyn, T., & García, O. (2019). Translanguaging as an act of transformation: Restructuring teaching and learning for emergent bilingual students. In L. C. Oliveira (Ed.), The handbook of TESOL in K-12 (1st ed., pp. 69–82). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlbacher, J., & Reeger, U. (2020). Globalization, immigration and ethnic diversity: The exceptional case of Vienna. In S. Musterd (Ed.), Handbook of urban segregation. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pichon, E., Wattar, D., Naji, M., Cha, H. R., Jia, Y., & Tariq, K. (2024). Towards linguistically and culturally responsive curricula: The potential of reciprocal knowledge in STEM education. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 37(1), 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, T. (Ed.). (2010). Teacher preparation for linguistically diverse classrooms (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (Eds.). (2011). Teacher preparation for linguistically diverse classrooms: A resource for teacher educators. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2014). Bilingual community education and multilingualism—Beyond heritage languages in a global city. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14(4), 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Practice, 31(2), 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, W. S., Kyuchukov, H., & Villiers, J. D. (2017). ‘We don’t talk Gypsy here’: Minority language policies in Europe. Journal of Language and Cultural Education, 5(2), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberwimmer, K., Vogtenhuber, S., Lassnigg, L., & Schreiner, C. (2019). Nationaler bildungsbericht österreich 2018—Band 1 das schulsystem im spiegel von daten und indikatoren. Leykam. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce, O. A., & Pagán-Maldonado, N. (2015). Mixed methods research in education: Capturing the complexity of the profession. International Journal of Educational Excellence, 1(1), 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilutskaya, M. (2021). Examining pedagogical translanguaging: A systematic review of the literature. Languages, 6(4), 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røyneland, U., & Blackwood, R. (Eds.). (2022). Multilingualism across the lifespan. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Schroedler, T., Purkarthofer, J., & Cantone, K. F. (2024). The prestige and perceived value of home languages. Insights from an exploratory study on multilingual speakers’ own perceptions and experiences of linguistic discrimination. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45(9), 3762–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selting, M., Auer, P., Barth-Weingarten, D., Bergmann, J. R., Bergmann, P., Birkner, K., Couper-Kuhlen, E., Deppermann, A., Gilles, P., Günthner, S., Hartung, M., Kern, F., Mertzlufft, C., Meyer, C., Morek, M., Oberzaucher, F., Peters, J., Quasthoff, U., Schütte, W., … Uhmann, S. (2009). Gesprächsanalytisches transkriptionssystem 2 (GAT 2). Gesprächsforschung-Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion, 10, 353–402. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Austria. (2022). More than a quarter of the total Austrian population has a migration background. Statistical yearbook migration & integration 2022. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/fileadmin/announcement/2022/07/20220725MigrationIntegration2022EN.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Strunk, K. K., & Locke, L. A. (2019). Research methods for social justice and equity in education. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, J., & King, B. (2022). Using informal conversations in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, 16094069221085056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K. S. (2018). Lost and found in translation: Guidelines for reporting research data in an ‘other’ language. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 19(3), 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, K. W. H., & Li, W. (2024). Mobilising multilingual and multimodal resources for facilitating knowledge construction: Implications for researching translanguaging and multimodality in CLIL classroom context. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C. (2006). Unreliable narrators? ‘Inconsistency’ (and some inconstancy) in interviews. Qualitative Research, 6(3), 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. J. (2014). Flexible multilingual education: Putting children’s needs first. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Weidl, M. (2022). Which multilingualism do you speak? Translanguaging as an integral part of individuals’ lives in the Casamance, Senegal. Journal of the British Academy, 27, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidl, M., & Erling, E. J. (2023). Kultursensible bildung, mehrsprachigkeit und englischlernen: Einblicke in einen udele-workshop an der universität wien. Schulheft, 191. [Google Scholar]

- Weidl, M., & Goodchild, S. (2025). Multilingualism triangulated: A systematic method for analysing multilingual contexts. Multilingual Margins: A Journal of Multilingualism from the Periphery, 11(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessendorf, S. (2016). Second-generation transnationalism and roots migration: Cross-border lives. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Yuval-Davis, N. (2006). Belonging and the politics of belonging. Patterns of Prejudice, 40(3), 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weidl, M.; Erling, E.J. Exploring Multilingualism to Inform Linguistically and Culturally Responsive English Language Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060763

Weidl M, Erling EJ. Exploring Multilingualism to Inform Linguistically and Culturally Responsive English Language Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):763. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060763

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeidl, Miriam, and Elizabeth J. Erling. 2025. "Exploring Multilingualism to Inform Linguistically and Culturally Responsive English Language Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060763

APA StyleWeidl, M., & Erling, E. J. (2025). Exploring Multilingualism to Inform Linguistically and Culturally Responsive English Language Education. Education Sciences, 15(6), 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060763