Abstract

Emotional exhaustion in schoolteachers is a critical issue due to its detrimental effects on teachers’ mental health and its potential negative impact on students’ academic outcomes. This study aimed to develop and validate the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES). The research was conducted in three phases. First, the scale items were developed and evaluated by expert judges using Aiken’s V for content validation. Second, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on a sample of 153 teachers to identify the scale’s factor structure. Finally, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted with a sample of 473 Chilean teachers to validate the factor structure. The EFA revealed a two-factor structure comprising Emotional Fatigue (EF) and Emotional Hopelessness (EH), which was subsequently confirmed in the CFA. The model demonstrated a satisfactory fit to the data: χ2(32) = 142.383, p < 0.001; CMIN/DF = 1.651. The goodness-of-fit indices were robust (GFI = 0.933, NFI = 0.952, IFI = 0.981, TLI = 0.974, CFI = 0.980), and the RMSEA was 0.065, indicating an acceptable model fit. The TEES is a valid and reliable instrument for assessing emotional exhaustion in teachers. These findings are particularly relevant in the Chilean educational context, where teachers’ mental health and its implications for the education system are of increasing concern. The TEES can serve as a valuable tool for the early identification of emotional exhaustion, ultimately contributing to teacher retention and the improvement of educational quality.

1. Introduction

Teaching is an emotionally demanding profession in which educators play a fundamental role in students’ academic and personal development (Brackett, 2024; Hoffmann & De France, 2024). The quality and effectiveness of teachers significantly influence educational outcomes, making their contributions essential to the success of any institution (Ghahramanian et al., 2024). In addition to instructional tasks such as lesson planning and assessment, teachers are exposed to intense emotional demands that arise from student behavior, administrative pressure, and societal expectations (Orrego-Tapia, 2023; K. Zhang et al., 2022). These conditions can trigger adverse psychological responses and affect their mental health, potentially leading to demotivation, absenteeism, and attrition from the profession (Salce Diaz, 2020).

Within the field of occupational health, work-related stress, emotional exhaustion, and burnout are recognized as interrelated but distinct constructs. Work stress refers to a temporary response to excessive demands, while emotional exhaustion—often considered the core component of burnout—is characterized by persistent fatigue, emotional depletion, and reduced psychological resilience resulting from prolonged stress exposure (Dávila Morán et al., 2023; Edú-Valsania et al., 2022; Motta, 2024). Among educators, chronic stress elevates the risk of mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, and burnout (Cortés-Álvarez et al., 2023), making emotional exhaustion an urgent concern in the education sector (Rumschlag, 2017). Recent studies have deepened the understanding of the consequences of teacher emotional exhaustion, linking it not only to individual impairments but also to critical organizational and educational variables. For instance, it has been associated with decreased work engagement (Lusiana et al., 2025), the deterioration of the school climate (Mai, 2025), and increased intentions to leave the profession (Gonzales et al., 2025).

Emotional exhaustion in teachers typically manifests as deep fatigue, decreased energy, and limited emotional availability toward students and the work environment (Day & Gu, 2013; Liu et al., 2020; Philipp & Schüpbach, 2010; Vargas Rubilar & Oros, 2021). This state can erode professional performance, hinder the management of academic and behavioral challenges in the classroom (Alessandri et al., 2021; Thanacoody et al., 2014), and ultimately impair student outcomes (Allcoat & von Mühlenen, 2018; Valiente et al., 2020). In addition to psychological consequences, emotional exhaustion is associated with a range of physical symptoms including sleep disturbances, gastrointestinal issues, and immune dysfunction (Baeriswyl et al., 2021; Bi & Ye, 2021; Hoffmann & De France, 2024; Martínez-Líbano et al., 2023; Maslach, 2018).

Despite being the core component of burnout (Maslach, 2018; Maslach et al., 2001; Seidler et al., 2014), accurately measuring emotional exhaustion in teachers remains a challenge (Bettini et al., 2017). Most existing assessment tools are designed for general stress or burnout evaluation (Ledikwe et al., 2018) and fail to capture the unique stressors of teaching (König & Kramer, 2016). The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) (Maslach et al., 1997) is the most widely recognized burnout measure, assessing emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. While a version tailored for educators, the Maslach Burnout Inventory—Educators Survey (MBI-ES) (Maslach et al., 1996), exists, it evaluates multiple constructs beyond emotional exhaustion. Other tools, such as the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) (Kristensen et al., 1999) and the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) (Demerouti & Bakker, 2008), assess different burnout dimensions but do not focus specifically on emotional exhaustion in teachers.

While emotional exhaustion is widely acknowledged as the central dimension of burnout, it is theoretically distinct from the broader burnout syndrome. Burnout, as conceptualized by Maslach and colleagues, includes three components: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment (Maslach et al., 2001). However, recent theoretical models have argued that emotional exhaustion can be studied independently as a core affective outcome of chronic occupational stress (Chaves-Montero et al., 2025; Feuerhahn et al., 2013). Unlike depersonalization or diminished efficacy, emotional exhaustion reflects the direct depletion of emotional resources and is often the first and most prevalent manifestation of teacher distress (Aigerim & Almazhay, 2024; Martínez-Líbano & Yeomans, 2023). Focusing on this single dimension allows for more targeted assessment and intervention efforts, particularly in educational contexts where emotional labor is central to daily professional functioning.

Given the evolving challenges and working conditions in education—particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic—there is a pressing need for a dedicated, psychometrically robust scale that accurately assesses emotional exhaustion in teachers. Existing burnout measures fail to address the specific dimensions and triggers relevant to the teaching profession. Developing a specialized instrument would enable a more precise evaluation of emotional exhaustion, facilitating early identification and targeted interventions.

Study Objectives

The primary objective of the present study was to develop and validate the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) for schoolteachers. The secondary objectives included psychometrically validating the TEES in a sample of Chilean teachers, identifying the factorial structure of the instrument through exploratory and confirmatory analyses, and evaluating its convergent validity. Accordingly, the research question guiding this study was as follows: Is the TEES a valid and reliable instrument for measuring emotional exhaustion in Chilean teachers? This instrument was designed to provide an accurate and sensitive assessment of emotional exhaustion in teachers, helping educators, researchers, and policymakers better understand and address the factors contributing to teacher emotional exhaustion.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The present study on the development and validation of the TEES employed a mixed-methods research design (Hernández Sampieri, 2018), incorporating both exploratory and cross-sectional components.

2.2. Procedure

The research was divided into three phases.

2.2.1. Phase 1: Item Development and Content Validation (Exploratory Approach)

In this phase, a literature review of studies on emotional exhaustion in teachers was conducted. Additionally, subject-matter experts were consulted to evaluate the initial pool of items. Based on this process, 25 items were developed. After an initial analysis, these items were reviewed by experts, leading to the refinement and reduction of the scale to 18 items, which were then evaluated by a panel of 10 experts.

The experts assessed the items in terms of clarity, quality, and relevance. Using Aiken’s V for content validity analysis, items with a concordance index below 0.70 were eliminated. As a result, 15 items were retained for further evaluation in Phase 2.

2.2.2. Phase 2: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) (Cross-Sectional Approach)

The Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) was administered to a sample of 153 Chilean schoolteachers from the national education system. The sample was obtained using a convenience sampling method, which is considered suitable for conducting an exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

For an EFA to be conducted, the number of observations must exceed 50 (Hair et al., 2014). A common rule of thumb suggests that the minimum sample size should be at least five times the number of variables in the model. However, a widely accepted minimum threshold for EFA is 100 observations (Beavers et al., 2013; Ghaleb & Yaslioglu, 2024). Given these criteria, the sample size of 153 respondents surpasses the recommended minimum, ensuring the feasibility of the factor analysis while accounting for the complexity of the sample.

2.2.3. Phase 3: Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (Cross-Sectional Approach)

The Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) was administered to a new, larger sample of 473 Chilean teachers from the national education system. To assess convergent validity, the TEES was also applied alongside the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995).

Regarding sample size requirements for CFA, some authors suggest a minimum of 100 subjects (Kline, 2014), while others recommend more than 100 (Anderson & Gerbing, 1984; Wang et al., 2024). A commonly accepted range for an adequate CFA sample size is between 200 and 400 participants (Jackson, 2001). However, the most widely agreed-upon threshold suggests that CFA models should ideally be based on at least 250 participants (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Nemati-Vakilabad et al., 2024).

Given these recommendations, our study far exceeded the suggested minimum sample size, ensuring robust statistical power and model stability.

2.3. Development of the TEES

The Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) was developed based on a comprehensive review of the specialized literature, complemented by in-depth qualitative interviews with teachers and practicing psychologists. In its initial version, the TEES consisted of a preliminary pool of 25 meticulously designed items aimed at comprehensively capturing the construct of emotional exhaustion in the teaching profession.

Following expert feedback and refinement, the scale was reduced to 18 items, ensuring better construct validity. After further expert review, 13 items were retained for empirical testing. Subsequently, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted, leading to the elimination of three additional items. As a result, the final version of the TEES comprised 10 carefully selected items.

Each item was thoughtfully formulated to capture both the psychological dimensions of emotional exhaustion and its physical manifestations, both of which are critical to understanding its impact on teachers’ professional well-being.

2.4. Content Validity

For content validation, a panel of 10 experts—comprising academics and clinical professionals with extensive experience in mental health and education—was convened. The experts assessed each item using Aiken’s V to evaluate its relevance, clarity, and representativeness. Items with an Aiken’s V score below 0.70 were either discarded or revised, leading to the development of a preliminary scale consisting of 18 items.

2.5. Participants

In Phase 1, a panel of 10 experts participated in the content validity process. The experts were selected through convenience sampling, ensuring that all participants had extensive experience in educational psychology and practical work within the school context. To be included in the panel, experts were required to hold a doctoral degree (PhD) in education, psychology, or a related field, have a minimum of 10 years of professional experience in educational psychology or teaching, and possess direct experience working in school settings. Additionally, they needed to demonstrate expertise in the assessment and validation of psychological and educational measurement instruments.

Professionals who lacked direct experience in school settings, formal training in educational psychology, or psychometric validation were excluded from the panel. Likewise, individuals with less than 10 years of experience in the field of education or psychology were not considered for participation.

The final panel consisted of 40% women and 60% men, with an average age of 49.6 years (SD = 9.96) and an average of 23.5 years (SD = 12.09) of professional experience. Among the experts, 70% were teachers and 30% were educational psychologists, all holding doctoral degrees (PhDs).

In Phase 2, a total of 153 schoolteachers from the Chilean educational system participated, selected through convenience sampling. The teachers completed a questionnaire administered via Google Forms, after providing informed consent prior to participation. Demographic data were collected, and the preliminary version of the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) was administered.

To ensure the relevance and reliability of the sample, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were established. Inclusion criteria required that participants be licensed teachers actively engaged in direct classroom instruction with children and/or adolescents. Participants were also required to work in public or private schools, providing a representative sample of the Chilean educational system.

Exclusion criteria included individuals not currently teaching or those in administrative roles without direct classroom interaction. Teachers who worked exclusively with adult learners were also excluded, as their experiences may not accurately reflect the emotional demands of working with school-aged populations.

The sample for this phase and the subsequent exploratory factor analysis (EFA) comprised 153 teachers, of whom 118 (77%) were women and 35 (23%) were men, reflecting the gender distribution within the Chilean educational context. The participants had an average age of 38 years (SD = 9.94), indicating a broad age range among teachers. Additionally, the average amount of teaching experience was 11.6 years, suggesting that the sample possessed considerable professional expertise.

In the final phase (Phase 3), a total of 473 teachers from the Chilean educational system participated, selected through convenience sampling. The questionnaire was administered via Google Forms and included the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES), the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), and other sociodemographic variables.

Inclusion criteria required participants to be credentialed teachers actively engaged in classroom instruction with children and/or adolescents. Additionally, participants had to be currently employed in the Chilean educational system at the time of the study.

Exclusion criteria ruled out individuals who were not in active classroom teaching roles, such as school administrators, support staff, or higher education faculty. Teachers who were not currently working as educators were also excluded.

All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. The final sample was composed of 74% women, 25.6% men, and 0.4% who identified outside the binary gender categories. The average age of the participants was 38.6 years (SD = 9.63).

2.6. Data Analysis

All collected data were first organized and prepared using Microsoft Excel, which included data cleaning, response coding, and structuring the dataset for further analysis. Subsequently, SPSS Version 25 (IBM, 2017) was used to conduct descriptive and exploratory data analyses, including the assessment of measures of central tendency and dispersion and the inspection of frequency distributions for each item on the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES).

To establish content validity in the first phase, data from expert ratings were analyzed using Aiken’s V coefficient (Pastor, 2018) to quantify the degree of agreement among experts regarding the relevance, clarity, and representativeness of each item. Items with an Aiken’s V score below 0.70 were eliminated or revised to ensure content validity.

In the second phase, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted in SPSS to examine the underlying structure of the scale and determine the optimal number of factors. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used for factor extraction, followed by Varimax rotation to enhance interpretability. To assess the adequacy of the data for factor analysis, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were performed, ensuring that the dataset met the necessary assumptions for valid factor extraction.

For the third phase, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS Version 24 (Arbuckle, 2014) to test the factor structure identified in the EFA through structural equation modeling (SEM). Several goodness-of-fit indices were calculated to assess the model’s adequacy, including chi-square (χ2), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The model’s fit was evaluated based on the following criteria: CFI ≥ 0.90, TLI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA < 0.08, SRMR < 0.08, and a goodness-of-fit p-value > 0.05 (Cangur & Ercan, 2015; X. Zhang & Savalei, 2016).

To further establish the reliability of the TEES, Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω) were calculated for each factor using SPSS. These reliability coefficients provided a robust estimate of internal consistency, reinforcing the validity and reliability of the study’s findings.

2.7. Ethical Criteria

This study was approved by the Central Bioethics Committee of Universidad Andrés Bello under registry number 024/2022. It is important to note that no personally identifiable information was collected from participants.

Prior to participation, all individuals provided informed consent, confirming their voluntary involvement in the study. No participants received any form of compensation for their participation.

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1: Content Validity

To ensure the construct validity of the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES), a structured content validation process was carried out in two expert judgment rounds. Initially, an item pool of 25 statements was generated based on a literature review and qualitative interviews with teachers and psychologists. These items were designed to capture the psychological and behavioral manifestations of emotional exhaustion specific to the teaching profession.

A panel of five experts—specialists in educational psychology and mental health—was invited to evaluate the items using a standardized evaluation grid. Each expert received a written operational definition of emotional exhaustion and rated the items according to three predefined criteria: Relevance, the extent to which each item reflected a central aspect of emotional exhaustion in the teaching context; clarity, the linguistic precision and semantic comprehensibility of the item for potential respondents; and representativeness, the degree to which the item captured a unique and essential feature of the construct without redundancy.

Experts used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 5 = completely) to evaluate each item on the three criteria. Following this first round, items were refined and reduced to 18 based on qualitative feedback and statistical thresholds. Subsequently, a second round of expert judgment was conducted with 10 additional experts. Aiken’s V coefficient was calculated for each item to quantify inter-expert agreement, with a cut-off value of ≥0.70 used for item retention. Items falling below this threshold were either revised or eliminated. Table 1 presents the final Aiken’s V values for each item.

Table 1.

Analysis of the concordance of Aiken’s V performed by expert judges.

This dual-phase validation process ensured high content validity and alignment with the construct’s theoretical and contextual definition. The resulting version of the TEES was then pilot tested with a small group of teachers to confirm the clarity and interpretability of the retained items before proceeding to exploratory factor analysis. Aiken’s V was computed using the software developed by Merino Soto and Livia Segovia (2009) (see Table 1).

As a result, items 5, 11, 16, 17, and 18 were eliminated: “Every time I think about my job, I experience physical ailments (e.g., stomach ache, headache, etc.)”, “Thinking about the future of my teaching career no longer makes sense”, “I feel like I am stuck in this job as a teacher”, “There are days when I feel like I do not want to go to work as a teacher”, “I feel annoyed when a student asks too many questions or does not understand what I teach.”

Following this refinement, a pilot test of the revised scale was conducted with a small sample of teachers to gather additional feedback on the clarity, relevance, and potential ambiguity of the remaining items. The results of this pilot study were carefully analyzed, leading to final adjustments to the scale before its broader application.

3.2. Phase 2: Exploratory Factor Analysis

In the second phase of our research, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to examine the factor structure of the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES). For this purpose, the revised 13-item version of the scale was administered to a new sample. Descriptive statistics for the sample are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the TEES.

The skewness and kurtosis values presented in Table 2 were examined to assess the normality of the distribution of the items. In the context of social sciences, values between −2 and +2 are generally considered acceptable to assume univariate normality. All the items fell within this range, indicating that the data distribution was approximately normal.

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were conducted to assess the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The KMO value was 0.937, indicating excellent sampling adequacy. Bartlett’s test yielded a statistically significant result (χ2 = 1576.487, df = 78, p < 0.001), further justifying the application of factor analysis.

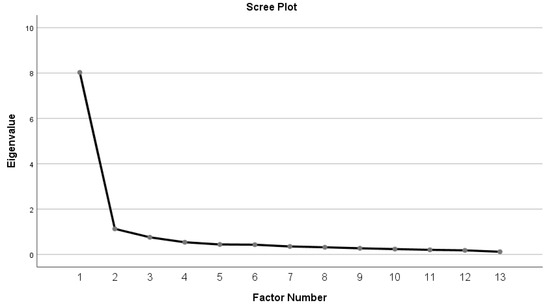

The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) identified two primary factors, which accounted for a substantial proportion of the variance in the responses (see Table 3). The initial eigenvalues for the first and second factors were 8.028 and 1.13, respectively, indicating their relevance to the scale’s structure. The first factor explained 61.751% of the total variance, while the second factor contributed an additional 8.69%, resulting in a cumulative variance of 70.441% explained by both factors. This factor structure is also visualized in the scree plot (Figure 1).

Table 3.

TEES total variance explained.

Figure 1.

Scree plot of TEES.

In summary, the findings indicate that two main factors account for a substantial proportion of the variance in TEES responses, supporting a two-dimensional factor structure for the scale.

The Maximum Likelihood method was used in the factor extraction phase, identifying two main factors. The first factor, “Emotional Fatigue” (EF), and the second, “Emotional Hopelessness” (EH), were clarified using a Varimax rotation to facilitate their interpretation. During this process, the initial and extraction communalities for each reagent were observed, which allowed the determination of the proportion of the variance of each variable explained by the extracted factors. The factor matrix was carefully examined to interpret the loading of each reagent on the identified factors. When performing the rotation analysis, it was decided to eliminate item 2, since its factor loading in both factors is less than 0.5, which indicates that it does not correlate strongly with either. Secondly, items 6 and 10 were eliminated, since they loaded towards both factors, making their interpretation difficult (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Rotated factor matrix.

Finally, the internal consistency of the scale was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha, obtaining a value of 0.958, indicating high reliability. Additionally, McDonald’s omega was estimated, which turned out to be 0.960, providing an additional measure of reliability and reinforcing the robustness of the developed scale. These results suggest that the scale, with its components of “Emotional Fatigue” and “Emotional Hopelessness”, has a valid and reliable factorial structure, making it suitable for measurement in the educational context.

3.3. Phase 3: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To confirm the structure proposed in the exploratory factor analysis, a final application of the TEES was carried out on a larger sample.

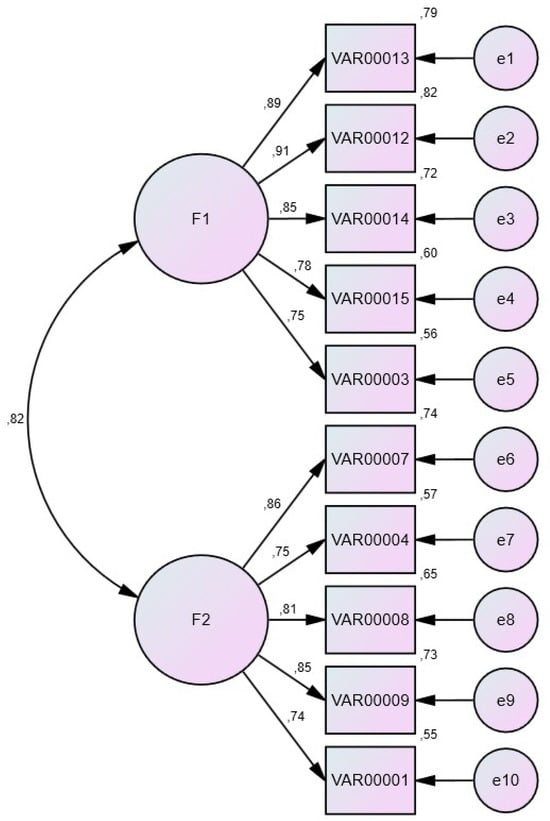

The model fit was assessed by a series of indices (see Table 5). The chi-square test resulted in a value of χ2 (32) = 142.383, p = 0.000 indicating statistical significance. The goodness-of-fit index (GFI) was 0.933, and the adjusted GFI (AGFI) was 0.891, suggesting a good fit of the model to the data. The comparative fit indices (NFIs) and incremental comparative fit indices (CFIs) showed excellent values (NFI = 0.952; CFI = 0.980), and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) was 0.974. Finally, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.065, with a 90% confidence interval of 0.032 to 0.095, which is consistent with a good model fit (see Figure 2).

Table 5.

Summary of model fit indices.

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the TEES.

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework to test the two-factor structure identified in the EFA: “Emotional Fatigue” and “Emotional Hopelessness.” The model specified 10 observed variables (items) loading onto their respective latent factors, with no cross-loadings allowed. The factors were allowed to correlate, reflecting the theoretical assumption that both dimensions represent interrelated components of emotional exhaustion. The obtained fit indices indicated a good model fit, supporting the proposed latent structure. These results confirm the robustness of the factorial structure and reinforce the construct validity of the TEES within a SEM context.

3.4. Convergent Validity

Regarding validity in relation to other variables, a correlational analysis was performed between the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) and the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), taking into account the theoretical relevance of the relationship between both constructs. Positive relationships were obtained between the Emotional Fatigue (EF) and Emotional Hopelessness (EH) factors and the different dimensions of the DASS-21 (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlations between TEES and DASS-21.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to develop and validate the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) (Appendix A). Psychometric analyses demonstrated that the TEES exhibits excellent reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha (α) = 0.958 and McDonald’s omega (ω) = 0.960, indicating high internal consistency. A two-dimensional factor structure was identified, consisting of Emotional Fatigue (EF) and Emotional Hopelessness (EH). The convergent validity of the scale was established through its significant correlations with the DASS-21 measures of depression, anxiety, and stress. Specifically, the TEES correlated with depression (r = 0.681, p < 0.01); anxiety (r = 0.498, p < 0.01) and stress (r = 0.612, p < 0.01).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) confirmed the structural model, demonstrating a satisfactory fit to the data: χ2(32) = 142.383, p < 0.001, with a chi-square ratio over degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) of 1.651.The goodness-of-fit indices indicated a robust and adequate model fit: GFI = 0.933; NFI = 0.952; IFI = 0.981; TLI = 0.974; CFI = 0.980; RMSEA = 0.065.

The two identified factors—Emotional Fatigue (EF) and Emotional Hopelessness (EH)—are both critical components in assessing teachers’ emotional well-being, yet they capture distinct psychological dimensions. Emotional Fatigue (EF) primarily relates to fatigue and the emotional toll of teaching, encompassing feelings of depletion and strain resulting from professional demands. In contrast, Emotional Hopelessness (EH) reflects pessimism and a lack of motivation toward teaching, indicating a deeper sense of discouragement and disengagement from the profession.

EF can contribute to the development of depression, anxiety, and chronic stress, significantly impacting teachers’ mental health and leading to serious repercussions for their students (Agyapong et al., 2022). This issue has become even more pronounced following the COVID-19 pandemic, during which a high prevalence of mental health disorders has been reported in Chile (Martínez-Líbano & Yeomans-Cabrera, 2024). The chronic stress associated with EF can also have negative consequences on physical health, including sleep disturbances, headaches, hypertension, and a weakened immune system (Madigan et al., 2023; Madigan & Kim, 2021). Teachers experiencing EF may struggle to maintain focus and motivation, ultimately diminishing teaching effectiveness and learning outcomes in the classroom (Baeriswyl et al., 2021; Klusmann et al., 2022). Additionally, EF can reduce teachers’ patience and empathy, compromising the quality of their interactions with students and potentially leading to deterioration of the classroom climate and student well-being (Olivier et al., 2023; Rosensteel, 2020; K. Zhang et al., 2022), also linked to decreased job satisfaction and reduced commitment to the profession, increasing the likelihood of absenteeism and staff turnover (Anastasiou & Belios, 2020; Madigan & Kim, 2021). The effects of EF extend beyond the work environment, impacting teachers’ personal relationships and family life and ultimately lowering their overall quality of life (Braun et al., 2020; Pong, 2022). Moreover, emotionally exhausted teachers may exhibit reduced interest in professional development and less motivation to improve their pedagogical skills (Baeriswyl et al., 2021; Klusmann et al., 2022). In severe cases, this may lead teachers to consider leaving the profession, jeopardizing the stability of the educational system and reducing the availability of qualified teachers (Van Eycken et al., 2024). This phenomenon is currently affecting the Chilean educational system, posing a serious challenge for teacher retention and educational quality (Orrego-Tapia, 2023).

On the other hand, EH can cause teachers to lose motivation and a sense of vocation, diminishing their belief in the positive impact they can have on their students and the education system. This loss of purpose may result in reduced initiative and creativity in teaching (Ghasemi, 2022). Feelings of hopelessness can foster a sense of worthlessness and lack of purpose, increasing the risk of depression and anxiety and leading to a deterioration in teachers’ overall mental health (Ghasemi et al., 2023; Yarim & Çelik, 2021). This emotional state can also reduce teaching effectiveness, as educators may feel that their efforts are futile, negatively affecting the quality of their pedagogical practices and enthusiasm for teaching (Burić et al., 2020). Furthermore, EH can impair teachers’ ability to form meaningful relationships with both students and colleagues, potentially resulting in a less collaborative and supportive classroom and work environment (Raufelder & Kulakow, 2022). This emotional distress can heighten stress levels and contribute to burnout, manifesting as fatigue, irritability, and feelings of being overwhelmed (Pinheiro et al., 2024). Teachers experiencing EH may exhibit higher absenteeism rates or even consider leaving the profession, impacting the stability and continuity of the educational environment (Kılavuz & İnandı, 2022). This emotional state can also impair judgment and negatively affect decision-making, with potential consequences for classroom management and the implementation of effective instructional strategies (Blaine, 2022), and teachers experiencing this emotional state may display little interest in professional development and the continuous improvement of their skills, limiting both their personal and professional growth (Wong et al., 2023). EH is often accompanied by physical symptoms, such as headaches, digestive issues, and muscle tension, which can increase the use of medical services and sick leave (Moss et al., 2016; Suleman et al., 2021). This can have long-lasting effects on a teacher’s career trajectory, professional identity, and self-worth (Alshakhi & Le Ha, 2020).

The Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) was specifically designed to assess emotional exhaustion in teachers, offering several key advantages. Firstly, the TEES is tailored to the educational context, providing a specialized tool that accurately captures the unique challenges faced by teachers. Additionally, as a short-scale instrument, it minimizes respondent burden, facilitating its efficient administration across various educational settings. The development of the TEES addresses this gap, enabling more in-depth research on the impact of emotional exhaustion on teachers’ well-being and professional lives.

The psychometric results obtained in this study are consistent with previous international findings that conceptualize emotional exhaustion as a multidimensional construct, often linked to emotional depletion and professional disengagement (Gil-Monte & Peiró, 1999; Maslach et al., 1997). The two-factor structure identified in the TEES aligns with recent models that differentiate between affective fatigue and motivational hopelessness in the teaching profession. Moreover, the high reliability coefficients and satisfactory fit indices from the confirmatory factor analysis reinforce the theoretical coherence and structural validity of the scale within the framework of educational psychometrics.

These findings are further supported by similar validation studies. For example, the Serbian version of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI), applied to preschool teachers, reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.936 and a three-factor structure explaining 67.17% of the total variance (Piperac et al., 2021). These results substantiate the reliability and validity of the two-factor structure identified in the TEES, as well as the adequacy of the fit indices obtained in the confirmatory factor analysis.

Given the global nature of teacher burnout, particularly in the post-pandemic context, the TEES represents a valuable tool for international application. Its brevity and specificity to the teaching context make it adaptable for cross-cultural validation studies, supporting broader comparative research on teacher well-being in diverse educational systems.

4.1. Limitations and Projections of the Study

Although the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) has demonstrated validity and reliability, its development was based on a specific sample of Chilean teachers. Therefore, it is crucial to consider that cultural and contextual factors may influence the generalizability of the results.

Furthermore, the use of a non-probabilistic convenience sampling strategy limits the external validity of the findings. While the sample included educators from different institutions and regions, it may not represent the full diversity of the teaching population in Chile or other Latin American countries. This methodological limitation should be considered when interpreting the applicability of the TEES beyond the sampled group.

To strengthen the applicability of the TEES, further research should continue to examine its psychometric properties across diverse populations and educational contexts.

4.2. Future Projections

The Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) has the potential to further advance the study of emotional burnout in teachers. Conducting additional studies in diverse geographic and cultural contexts would be beneficial to validate the TEES across a broader range of teacher populations. Moreover, future research could explore the associations between emotional burnout and other critical factors, such as organizational climate, administrative support, and teachers’ personal characteristics.

Additionally, developing targeted interventions based on TEES findings could be a crucial step in proactively addressing emotional burnout in educational settings.

The findings of this study should be considered by educational policymakers for the development of strategies aimed at fostering a healthier work environment for teachers. This includes promoting work–life balance, reducing excessive workloads, and cultivating a supportive and collaborative atmosphere within educational institutions. Furthermore, the TEES results can be leveraged to advocate for additional resources and support for teachers, recognizing their fundamental role in the success of the educational system.

4.3. Practical Implications

The TEES provides educational administrators and mental health professionals with an important tool for early identification of emotional burnout in teachers. This could facilitate the implementation of well-being and psychological support programs specifically targeting this population. In addition, the results of the TEES can help teacher educators design and modify professional development programs that address critical aspects of teachers’ emotional well-being.

5. Conclusions

The present study aimed to develop and validate a psychometric scale designed to measure emotional exhaustion in teachers. For this purpose, the Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) was created, comprising two main factors: Emotional Fatigue (EF) and Emotional Hopelessness (EH). These dimensions are essential for advancing the understanding of emotional exhaustion within the teaching profession.

The analyses demonstrated that the TEES exhibits excellent fit indices (CFI = 0.980, TLI = 0.974, RMSEA = 0.065) and high reliability levels (α = 0.958, ω = 0.960). These findings confirm that the TEES is a robust and reliable instrument capable of providing valuable information for researchers, mental health and wellness professionals, educational administrators, and policymakers.

The implementation of the TEES can facilitate the early detection of emotional exhaustion in teachers, enabling the development of targeted intervention strategies and action plans. This, in turn, could help prevent the adverse consequences that emotional exhaustion may have on educators’ mental health and quality of life, ultimately benefiting both teachers and the educational system as a whole.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board Central Bioethics Committee of Universidad Andrés Bello under registry number 024/2022, 7 September 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be requested by email to the author of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Spanish version

Teachers Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES)

Instrucciones

A partir de su experiencia en el último mes relacionada con su labor docente. A continuación, encontrará una serie de afirmaciones que describen diferentes sentimientos y percepciones acerca de su trabajo. Por favor, indique en qué medida está de acuerdo con cada una de estas afirmaciones utilizando la siguiente escala: 1. Totalmente en desacuerdo; 2. En desacuerdo; 3 Ni desacuerdo ni de acuerdo; 4. De acuerdo y 5. Totalmente de acuerdo. Seleccione esta opción si la afirmación describe su experiencia perfectamente o casi siempre. Por favor, responda a cada afirmación de manera honesta y basándose en sus propias experiencias recientes. No hay respuestas “correctas” o “incorrectas”. Su opinión es lo que cuenta.

| # | Factor | Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | EF | El trabajo como docente me produce una gran tensión | |||||

| 2 | EH | Cada vez que pienso en mi trabajo como docente me angustio | |||||

| 3 | EF | Hay días que me cuesta dormir bien por estar pensando en mi labor docente | |||||

| 4 | EF | Me siento emocionalmente agotado/a debido a mi labor docente | |||||

| 5 | EF | Me siento cansado/a de pensar en cómo hacer que mis alumnos aprendan | |||||

| 6 | EF | Pensar en mi labor docente me produce ansiedad y estrés | |||||

| 7 | EH | Me siento desanimado en pensar en mi labor docente | |||||

| 8 | EH | Siento que ya no puedo más con mi labor docente | |||||

| 9 | EH | Siento que estoy cada vez más lejos de conseguir mis objetivos laborales | |||||

| 10 | EH | Creo que ya no tengo las ganas de antes de realizar docencia |

Corrección: Sumar todos los puntajes de manera directa.

Interpretación:

Rango: 11 a 26: Nivel Bajo de Agotamiento Emocional Docente

Rango: 27 a 37: Nivel Moderado de Agotamiento Emocional Docente

Rango: 38 a 50: Nivel Alto de Agotamiento Emocional

English version

Teachers Emotional Exhaustion Scale (TEES) (English version)

Instructions

Based on your experience in the past month related to your teaching work. Below are a series of statements that describe different feelings and perceptions about your job. Please indicate how much you agree with each of these statements using the following scale: 1. Strongly Disagree; 2. Disagree; 3. Neither Disagree nor Agree; 4. Agree; and 5. Strongly Agree. Select this option if the statement describes your experience perfectly or almost always. Please respond to each statement honestly and based on your own recent experiences. There are no “right” or “wrong” answers. Your opinion is what counts.

| # | Factor | Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | EF | My teaching job puts much stress on me | |||||

| 2 | EH | Every time I think about my teaching job, I get anxious. | |||||

| 3 | EF | There are days when I have trouble sleeping well because I am thinking about my teaching job. | |||||

| 4 | EF | I feel emotionally exhausted because of my teaching job. | |||||

| 5 | EF | I feel tired of thinking about how to make my students learn. | |||||

| 6 | EF | Thinking about my teaching job makes me anxious and stressed. | |||||

| 7 | EH | I feel discouraged thinking about my teaching job. | |||||

| 8 | EH | I feel like I can’t do my teaching job anymore. | |||||

| 9 | EH | I feel like I’m getting further and further away from achieving my work goals. | |||||

| 10 | EH | I don’t think I have the desire to teach that I used to have. |

Correction: Add all scores directly.

Interpretation:

Range: 11 to 26: Low Level of Teacher Emotional Exhaustion

Range: 27 to 37: Moderate Level of Teacher Emotional Exhaustion

Range: 38 to 50: High Level of Exhaustion

References

- Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L., & Wei, Y. (2022). Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aigerim, S., & Almazhay, Y. (2024). How does teacher emotional burnout syndrome affect teachers’ development? Yessenov Science Journal, 48(3), 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G., De Longis, E., & Cepale, G. (2021). Emotional inertia emerges after prolonged states of exhaustion: Evidences from a measurement burst study. Motivation and Emotion, 45(4), 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcoat, D., & von Mühlenen, A. (2018). Learning in virtual reality: Effects on performance, emotion and engagement. Research in Learning Technology, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshakhi, A., & Le Ha, P. (2020). Emotion labor and affect in transnational encounters: Insights from western-trained TESOL professionals in Saudi Arabia. Research in Comparative and International Education, 15(3), 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, S., & Belios, E. (2020). Effect of age on job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion of primary school teachers in Greece. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(2), 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1984). The effect of sampling error on convergence, improper solutions, and goodness-of-fit indices for maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis. Psychometrika, 49, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2014). Amos (Version 23). IBM SPSS. [Google Scholar]

- Baeriswyl, S., Bratoljic, C., & Krause, A. (2021). How homeroom teachers cope with high demands: Effect of prolonging working hours on emotional exhaustion. Journal of School Psychology, 85, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavers, A. S., Lounsbury, J. W., Richards, J. K., Huck, S. W., Skolits, G. J., & Esquivel, S. L. (2013). Practical considerations for using exploratory factor analysis in educational research. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 18(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettini, E., Jones, N., Brownell, M., Conroy, M., Park, Y., Leite, W., Crockett, J., & Benedict, A. (2017). Workload manageability among novice special and general educators: Relationships with emotional exhaustion and career intentions. Remedial and Special Education, 38(4), 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y., & Ye, X. (2021). The effect of trait mindfulness on teachers’ emotional exhaustion: The chain mediating role of psychological capital and job engagement. Healthcare, 9(11), 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaine, J. (2022). Teachers’ mental wellbeing during ongoing school closures in Hong Kong. Education Journal, 11(4), 137–150. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Judith-Blaine/publication/366325191_Teachers’_Mental_Wellbeing_During_Ongoing_School_Closures_in_Hong_Kong/links/639c4612e42faa7e75cad535/Teachers-Mental-Wellbeing-During-Ongoing-School-Closures-in-Hong-Kong.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Brackett, M. A. (2024). Giving educators permission to feel adults in schools are feeling strong emotions. Tuning in to these feelings more fully can help them cope. Educational Leadership; Assoc Supervision Curriculum Development 1703 N Beauregard ST, Alexandria …. Available online: https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/giving-educators-permission-to-feel (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Braun, S. S., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Roeser, R. W. (2020). Effects of teachers’ emotion regulation, burnout, and life satisfaction on student well-being. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 69, 101151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I., Slišković, A., & Sorić, I. (2020). Teachers’ emotions and self-efficacy: A test of reciprocal relations. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangur, S., & Ercan, I. (2015). Comparison of model fit indices used in structural equation modeling under multivariate normality. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 14(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves-Montero, A., Blanco-Miguel, P., & Ríos-Vizcaíno, B. (2025). Analysis of the predictors and consequential factors of emotional exhaustion among social workers: A systematic review. Healthcare, 13(5), 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Álvarez, N. Y., Garduño, A. S., Sánchez-Vidaña, D. I., Marmolejo-Murillo, L. G., & Vuelvas-Olmos, C. R. (2023). A longitudinal study of the psychological state of teachers before and during the COVID-19 outbreak in Mexico. Psychological Reports, 126(6), 2789–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, C., & Gu, Q. (2013). Resilient teachers, resilient schools: Building and sustaining quality in testing times (1st ed., Vol. 1). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila Morán, R. C., Sánchez Soto, J. M., López Gómez, H. E., Espinoza Camus, F. C., Palomino Quispe, J. F., Castro Llaja, L., Díaz Tavera, Z. R., & Ramirez Wong, F. M. (2023). Work stress as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Sustainability, 15(6), 4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2008). The oldenburg burnout inventory: A good alternative to measure burnout and engagement. Handbook of Stress and Burnout in Health Care, 65(7), 1–25. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46704152_The_Oldenburg_Burnout_Inventory_A_good_alternative_to_measure_burnout_and_engagement (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Edú-Valsania, S., Laguía, A., & Moriano, J. A. (2022). Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerhahn, N., Stamov-Roßnagel, C., Wolfram, M., Bellingrath, S., & Kudielka, B. M. (2013). Emotional exhaustion and cognitive performance in apparently healthy teachers: A longitudinal multi-source study. Stress and Health, 29(4), 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghahramanian, A., Bagheriyeh, F., Aghajari, P., Asghari-Jafarabadi, M., Abolfathpour, P., Rahmani, A., Nabighadim, A., & Hajieskandar, A. (2024). The intention to leave among academics in Iran: An examination of their work-life quality and satisfaction. BMC Nursing, 23(1), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, M., & Yaslioglu, M. (2024). Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for social and behavioral sciences studies: Steps sequence and explanation. Journal of Organizational Behavior Review, 6(1), 69–108. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jobreview/issue/82893/1395927 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Ghasemi, F. (2022). Teachers’ demographic and occupational attributes predict feelings of hopelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 913894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, F., Mohammadnia, Z., & Gholami, Z. (2023). Individual differences in teacher hopelessness: Examining the significance of personal and professional factors. Psychology Hub, 40(2), 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Monte, P. R., & Peiró, J. M. (1999). Validez factorial del Maslach Burnout Inventory en una muestra multiocupacional. Psicothema, 11, 679–689. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, Y., Guevara-Delgado, N., Alcahuaman, J., Jiménez, V., & Osorio, P. (2025). Burnout syndrome and intention to leave: An analysis of its impact through a systematic review 2015–2025. Journal of Ecohumanism, 4(1), 4370–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Sampieri, R. (2018). Metodología de la investigación: Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta. McGraw Hill México. Available online: https://books.google.cl/books?hl=es&lr=&id=5A2QDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Hernández+Sampieri+2018&ots=TkVkTVZmN-&sig=GRHw5ZzUS2555WMRyvSgtZ6_xyE&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Hernández%20Sampieri%202018&f=false (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Hoffmann, J. D., & De France, K. (2024). Teaching emotion regulation in schools. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2024-33137-057 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. (2017). IBM SPSS statistics for windows. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-25 (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Jackson, D. L. (2001). Sample size and number of parameter estimates in maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis: A Monte Carlo investigation. Structural Equation Modeling, 8(2), 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılavuz, T., & İnandı, Y. (2022). The relationship of the career barriers of women teachers with their perceptions of professional social support and hopelessness level: Evidence from Turkey. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. (2014). An easy guide to factor analysis (Vol. 1). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, U., Aldrup, K., Roloff, J., Lüdtke, O., & Hamre, B. K. (2022). Does instructional quality mediate the link between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and student outcomes? A large-scale study using teacher and student reports. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(6), 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, J., & Kramer, C. (2016). Teacher professional knowledge and classroom management: On the relation of general pedagogical knowledge (GPK) and classroom management expertise (CME). ZDM, 48, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T. S., Borritz, M., Villadsen, E., & Christensen, K. B. (1999). Copenhagen burnout inventory. Work & Stress, 19(3), 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledikwe, J. H., Kleinman, N. J., Mpho, M., Mothibedi, H., Mawandia, S., Semo, B., & O’Malley, G. (2018). Associations between healthcare worker participation in workplace wellness activities and job satisfaction, occupational stress and burnout: A cross-sectional study in Botswana. BMJ Open, 8(3), e018492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Zou, H., Wang, H., Xu, X., & Liao, J. (2020). Do emotional labour strategies influence emotional exhaustion and professional identity or vice versa? Evidence from new nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(2), 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P., & Lovibond, S. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Scales (DASS). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusiana, W., Riyadi, S., & Sumiati, S. (2025). The influence of transformational leadership, workload, and work engagement on emotional exhaustion and organizational citizenship behavior at PT. Wangta Agung Surabaya. Journal of Social Research, 4(2), 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Towards an understanding of teacher attrition: A meta-analysis of burnout, job satisfaction, and teachers’ intentions to quit. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D. J., Kim, L. E., Glandorf, H. L., & Kavanagh, O. (2023). Teacher burnout and physical health: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Research, 119, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y. (2025). Unveiling the role of classroom climate in Chinese EFL teachers’ perceptions of their emotional exhaustion and attrition. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 132(1), 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Líbano, J., Torres-Vallejos, J., Oyanedel, J. C., González-Campusano, N., Calderón-Herrera, G., & Yeomans-Cabrera, M. M. (2023). Prevalence and variables associated with depression, anxiety, and stress among Chilean higher education students, post-pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1139946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Líbano, J., & Yeomans, M.-M. (2023). Emotional exhaustion variables in trainee teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(2), 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Líbano, J., & Yeomans-Cabrera, M.-M. (2024). Depression, anxiety, and stress in the Chilean educational system: Children and adolescents post-pandemic prevalence and variables. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1407021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. (2018). Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research (pp. 19–32). CRC Press. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9780203741825-3/burnout-multidimensional-perspective-christina-maslach (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). Maslach burnout inventory. Scarecrow Education. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-09146-011 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Schwab, R. L. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory-educators survey (MBI-ES). MBI Manual, 3, 27–32. Available online: https://www.mindgarden.com/316-mbi-educators-survey (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino Soto, C., & Livia Segovia, J. (2009). Intervalos de confianza asimétricos para el índice la validez de contenido: Un programa Visual Basic para la V de Aiken. Anales de Psicología, 25(1), 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, M., Good, V. S., Gozal, D., Kleinpell, R., & Sessler, C. N. (2016). A critical care societies collaborative statement: Burnout syndrome in critical care health-care professionals. A call for action. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 194(1), 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, R. W. (2024). Burnout syndrome: Characteristics and interventions. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati-Vakilabad, R., Khoshbakht-Pishkhani, M., Maroufizadeh, S., & Javadi-Pashaki, N. (2024). Translation and validation of the Persian version of the perception to care in acute situations (PCAS-P) scale in novice nurses. BMC Nursing, 23(1), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, E., Lazariuk, L., Archambault, I., & Morin, A. J. S. (2023). Teacher emotional exhaustion: The synergistic roles of self-efficacy and student–teacher relationships. Social Psychology of Education, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrego-Tapia, V. (2023). Rotación y deserción docente en Chile:¿ Por qué es importante y cómo prevenirla y/o mitigarla? Revista de Estudios y Experiencias En Educación, 22(50), 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, B. F. R. (2018). Índice de validez de contenido: Coeficiente V de Aiken. Pueblo Continente, 29(1), 193–197. Available online: https://journal.upao.edu.pe/index.php/PuebloContinente/article/view/991 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Philipp, A., & Schüpbach, H. (2010). Longitudinal effects of emotional labour on emotional exhaustion and dedication of teachers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(4), 494. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2010-22711-012 (accessed on 1 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, M. d. D. C., de Oliveira Torres, C. M., de Almeida Neto, H., & Gedrat, D. (2024). Causes and reflexes of physical and psychological health in high school teachers. Acta Scientiarum. Health Sciences, 46(1), e64677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperac, P., Todorovic, J., Terzic-Supic, Z., Maksimovic, A., Karic, S., Pilipovic, F., & Soldatovic, I. (2021). The validity and reliability of the Copenhagen burnout inventory for examination of burnout among preschool teachers in Serbia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pong, H. K. (2022). The correlation between spiritual well-being and burnout of teachers. Religions, 13(8), 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raufelder, D., & Kulakow, S. (2022). The role of social belonging and exclusion at school and the teacher–student relationship for the development of learned helplessness in adolescents. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosensteel, L. J. (2020). A predictive and causal-comparative analysis of teacher burnout and emotional empathy among K-12 public school teachers [Ph.D. dissertation, Liberty University]. Available online: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/2373 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Rumschlag, K. E. (2017). Teacher burnout: A quantitative analysis of emotional exhaustion, personal accomplishment, and depersonalization. International Management Review, 13(1), 22. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/322c7e643c75f9ac2f802880bbb5fc8c/1?cbl=28202&pq-origsite=gscholar (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Salce Diaz, F. (2020). Deserción escolar y calidad de los docentes en Chile. Revista de Análisis Económico, 35(2), 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, A., Thinschmidt, M., Deckert, S., Then, F., Hegewald, J., Nieuwenhuijsen, K., & Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2014). The role of psychosocial working conditions on burnout and its core component emotional exhaustion—A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 9(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, Q., Khattak, A. Z., & Hussain, I. (2021). Occupational stress: Associated factors, related symptoms, and coping strategies among secondary school-heads. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 36(4), 529–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanacoody, P. R., Newman, A., & Fuchs, S. (2014). Affective commitment and turnover intentions among healthcare professionals: The role of emotional exhaustion and disengagement. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(13), 1841–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente, C., Swanson, J., DeLay, D., Fraser, A. M., & Parker, J. H. (2020). Emotion-related socialization in the classroom: Considering the roles of teachers, peers, and the classroom context. Developmental Psychology, 56(3), 578. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2020-11553-016 (accessed on 1 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Van Eycken, L., Amitai, A., & Van Houtte, M. (2024). Be true to your school? Teachers’ turnover intentions: The role of socioeconomic composition, teachability perceptions, emotional exhaustion and teacher efficacy. Research Papers in Education, 39(1), 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Rubilar, N., & Oros, L. B. (2021). Stress and burnout in teachers during times of pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 756007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y., Jiang, T., & Shen, L. (2024). Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Chinese version of the intensive care oral care frequency and assessment scale. Heliyon, 10(1), e24025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L. P. W., Chen, G., & Yuen, M. (2023). Career development and the COVID-19 outbreak: Protective functions of career-related teacher support. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 52(6), 1118–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarim, M. A., & Çelik, S. (2021). Organizational anomie: A qualitative research on educational institutions. Open Journal for Educational Research, 5(2), 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K., Cui, X., Wang, R., Mu, C., & Wang, F. (2022). Emotions, illness symptoms, and job satisfaction among kindergarten teachers: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Sustainability, 14(6), 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., & Savalei, V. (2016). Bootstrapping confidence intervals for fit indexes in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(3), 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).