Mobile-Enhanced Outdoor Education for Tang Sancai Heritage Tourism: An Interactive Experiential Learning Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Experiential Tourism in ICH Contexts

2.2. Experiential Learning Theory for ICH Tourism Education

2.3. Mobile Learning Design for ICH Tourism Education

3. Application Design

3.1. Study Site Overview

3.2. Theoretical Framework for Design

3.3. Design Implementation

3.3.1. Activity Scenario: Seeking Challenging Tasks

3.3.2. Information Scenario: Critical Reflection

3.3.3. Interactive Scenario: Immersive Engagement

4. Experiment Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. Instruments

4.3. Procedures

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. ICH Knowledge Learning Outcomes

5.2. Experiential Learning Outcomes

5.3. Technology Acceptance: Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use

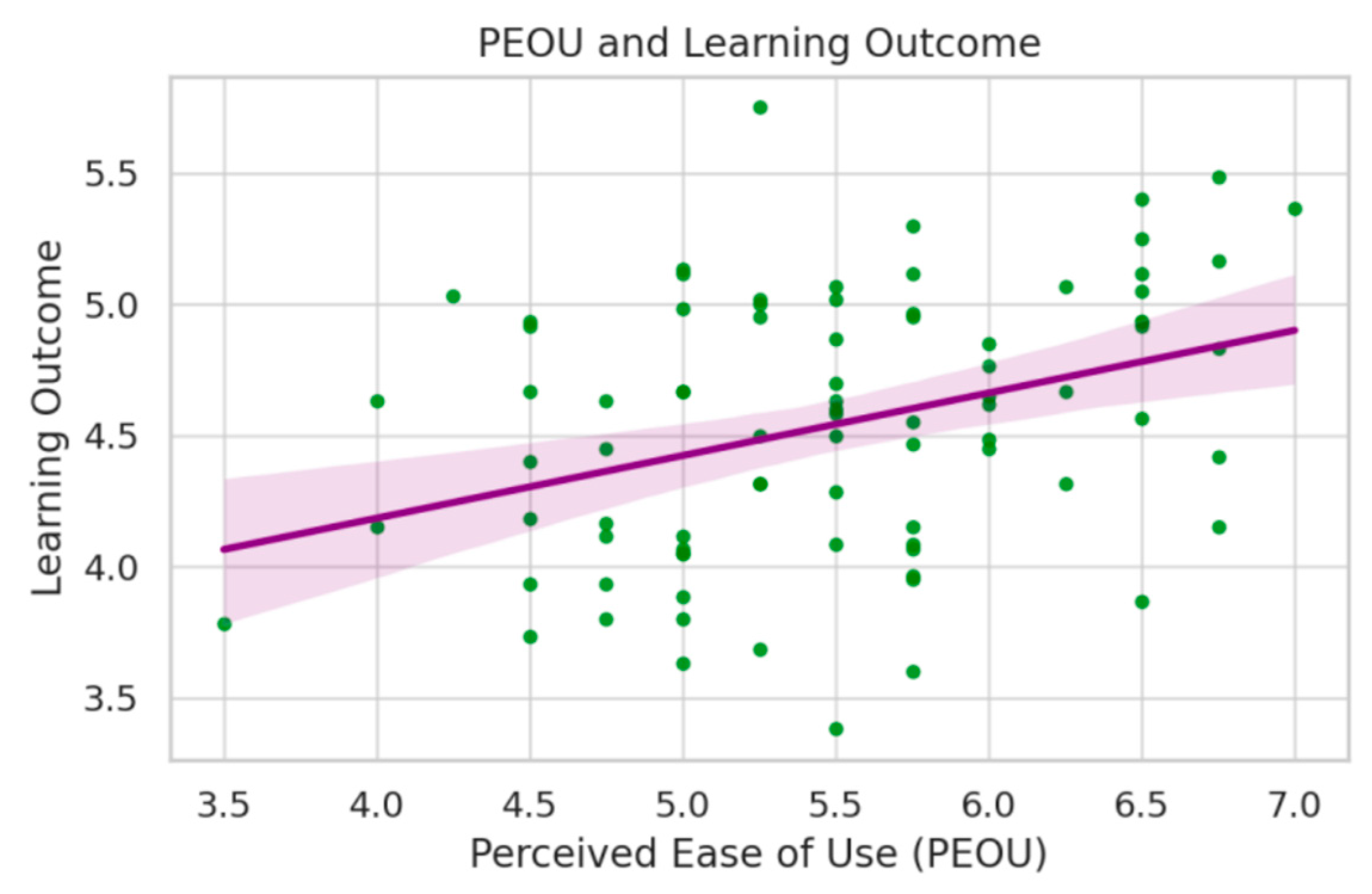

5.4. Predictive Effects of Technology Acceptance on Experiential Learning Outcomes

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Key Findings

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications for Learning in ICH Tourism

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdo, A. H. (2019). Digital heritage applications and its impact on cultural tourism. Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality, 17(1), 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M. A., Alamri, M. M., & Al-Rahmi, W. (2019). Applying the UTAUT model to explain the students’ acceptance of mobile learning system in higher education. IEEE Access, 7, 174673–174686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloqaily, A., Al-Nawayseh, M. K., Baarah, A. H., Salah, Z., Al-Hassan, M., & Al-Ghuwairi, A.-R. (2019). A neural network analytical model for predicting determinants of mobile learning acceptance. International Journal of Computer Applications in Technology, 60(1), 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives: Complete edition. Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, M. S., Yang, J., Frnda, J., Choi, A., Baghaei, N., & Ali, M. (2025). Metaverse and XR for cultural heritage education: Applications, standards, architecture, and technological insights for enhanced immersive experience. Virtual Reality, 29(2), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcodia, C., Abreu Novais, M., Cavlek, N., & Humpe, A. (2021). Educational tourism and experiential learning: Students’ perceptions of field trips. Tourism Review, 76(1), 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Colpas, P. P., Piñeres-Melo, M. A., Morales-Ortega, R.-C., Rodriguez-Bonilla, A.-F., Butt-Aziz, S., Naz, S., Contreras-Chinchilla, L. d. C., Romero-Mestre, M., & Vacca Ascanio, R. A. (2023). Tourism and conservation empowered by augmented reality: A scientometric analysis based on the science tree metaphor. Sustainability, 15(24), 16847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N. A. A., Ariffin, N. F. M., Ismail, N. A., & Alias, A. (2020). The non-formal education initiative of living heritage conservation for the community towards sustainable development. Asian Journal of Quality of Life, 5(18), 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, J. (2022). Re-live history: An immersive virtual reality learning experience of prehistoric intangible cultural heritage. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1032108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binbin, T., Sereerat, B.-O., Songsiengchai, S., & Thongkumsuk, P. (2024). The development of intangible cultural heritage curriculum based on experiential learning theory to improve undergraduate students understanding in intangible cultural heritage. World Journal of Education, 14(1), 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boboc, R. G., Băutu, E., Gîrbacia, F., Popovici, N., & Popovici, D.-M. (2022). Augmented reality in cultural heritage: An overview of the last decade of applications. Applied Sciences, 12(19), 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, K. (2022). High tech or high touch? Heritage encounters and the power of presence. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 28(11–12), 1228–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyani, I. P., Mardani, P. B., & Widianingsih, Y. (2023). Digital storytelling in cultural tourism: A sustainable communication approach at the lasem heritage foundation. International Journal of Management, Entrepreneurship, Social Science and Humanities, 6(1), 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.-X. (2024). Bridging tradition and technology: Gamification of intangible cultural heritage education through experiential gaming. IET Conference Proceedings CP907, 2024(28), 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Li, T., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Embodied cognition model for museum gamification cultural heritage communication a grounded theory study. npj Heritage Science, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Wang, X., Le, B., & Wang, L. (2024). Why people use augmented reality in heritage museums: A socio-technical perspective. Heritage Science, 12(1), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Suntikul, W., & King, B. (2020). Constructing an intangible cultural heritage experiencescape: The case of the Feast of the Drunken Dragon (Macau). Tourism Management Perspectives, 34, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.-Y., Chang, H.-L., & Wang, C.-S. (2024). Applying a wearable MR-based mobile learning system on museum learning activities for university students. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(9), 5744–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.-Y., Lee, K.-F., & Chen, Y.-L. (2019). Effects of a ubiquitous guide-learning system on cultural heritage course students’ performance and motivation. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 13(1), 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, F. M.-Y. (2024). Utilising technology as a transmission strategy in intangible cultural heritage: The case of cantonese opera performances. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 30(2), 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Csikzentmihaly, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (Vol. 1990). Harper & Row New York. [Google Scholar]

- Dagnino, F., Pozzi, F., Ceregini, A., Katos, A., & Grammalidis, N. (2018). Information and communication technologies and intangible cultural heritage education: Opportunities and challenges. Italian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(2), 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J., & Easterby-Smith, M. (1984). Learning and developing from managerial work experiences. Journal of Management Studies (Wiley-Blackwell), 21(2), 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Nunes, M., & Mayer, V. F. (2014). Mobile technology, games and nature areas: The tourist perspective. Tourism & Management Studies, 10(1), 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, J. D., Tolman, S., McBrayer, J. S., & Ballesteros, E. (2023). Reconceptualizing Kolb’s learning cycle as episodic & lifelong. Experiential Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 6(1), 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faella, P., Digennaro, S., & Iannaccone, A. (2025). Educational practices in motion: A scoping review of embodied learning approaches in school. In Frontiers in education (Vol. 10, p. 1568744). Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J. H., & Dierking, L. D. (2016). The museum experience revisited. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y. (2024). Current situation, problems and countermeasures of intangible cultural heritage inheritance and protection in college education. Academic Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 7(8), 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Yulfo, A. (2022). Transforming museum education through intangible cultural heritage. Journal of Museum Education, 47(3), 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geçikli, R., Turan, O., Lachytová, L., Dağlı, E., Kasalak, M., Uğur, S., & Guven, Y. (2024). Cultural heritage tourism and sustainability: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 16(15), 6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbheer, C. P., Khedo, K. K., & Bungaleea, A. (2022). Personalized and adaptive context-aware mobile learning: Review, challenges and future directions. Education and Information Technologies, 27(6), 7491–7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Lu, S., Shen, M., Huang, W., Yi, X., & Zhang, J. (2024). Differences in heritage tourism experience between VR and AR: A comparative experimental study based on presence and authenticity. ACM Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 17(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouda, M. (2022). Mobile applications in tourism: Examining the determinants of intention to use. International Journal of Technology and Human Interaction (IJTHI), 18(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.-I. D., Weber, J., Bastiaansen, M., Mitas, O., & Lub, X. (2019). Virtual and augmented reality technologies to enhance the visitor experience in cultural tourism. In Augmented reality and virtual reality: The power of AR and VR for business (pp. 113–128). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S., Yoon, J.-H., & Kwon, J. (2021). Impact of experiential value of augmented reality: The context of heritage tourism. Sustainability, 13(8), 4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincapié, M., Díaz, C., Zapata-Cárdenas, M.-I., Rios, H. de J. T., Valencia, D., & Güemes-Castorena, D. (2021). Augmented reality mobile apps for cultural heritage reactivation. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 93, 107281. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. (2004). Measuring learning outcomes in museums, archives and libraries: The Learning Impact Research Project (LIRP). International Journal of Heritage Studies, 10(2), 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocente, C., Ulrich, L., Moos, S., & Vezzetti, E. (2023). A framework study on the use of immersive XR technologies in the cultural heritage domain. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 62, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q. (2009). Tang sancai [Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford]. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, X., Tan, F., & Zhang, M. (2021). Digital application of intangible cultural heritage from the perspective of cultural ecology. Journal of Smart Tourism, 1(1), 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T., Chung, N., & Leue, M. C. (2015). The determinants of recommendations to use augmented reality technologies: The case of a Korean theme park. Tourism Management, 49, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettula, S., & Hyvönen, E. (2012, June 10–14). Process-centric cataloguing of intangible cultural heritage. CIDOC2012—Enriching Cultural Heritage (pp. 1–6), Helsinki, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillova, K., Lehto, X., & Cai, L. (2017). Tourism and existential transformation: An empirical investigation. Journal of Travel Research, 56(5), 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsabasis, P., Partheniadis, K., Gardeli, A., Vogiatzidakis, P., Nikolakopoulou, V., Chatzigrigoriou, P., & Vosinakis, S. (2021). Location-based games for cultural heritage: Applying the design thinking process. In CHI Greece 2021: 1st international conference of the ACM Greek SIGCHI chapter (pp. 1–8). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.-Z., Chen, C.-C., Kang, X., & Kang, J. (2022). Research on relevant dimensions of tourism experience of intangible cultural heritage lantern festival: Integrating generic learning outcomes with the technology acceptance model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 943277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Z., & Kang, X. (2023, March 22–25). Intangible cultural heritage based augmented reality mobile learning: Application development and heuristics evaluation. 2023 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (ECTI DAMT & NCON) (pp. 26–30), Phuket, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2019). The development of goal setting theory: A half century retrospective. Motivation Science, 5(2), 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.-J., & Hsiao, P.-W. (2023). Design of interactive learning materials with concept of sustainability integrated into Macau drunken dragon dance. Engineering Proceedings, 38(1), 12. [Google Scholar]

- Ma’arif, M., Muslim, S., & Sukardjo, M. (2023, October 12–13). An experiential learning model to facilitate the professional development of batik instructors through teaching videos. International Seminar and Conference on Educational Technology (ISCET 2022) (pp. 56–66), Jakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. (2013). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marto, A., Gonçalves, A., Melo, M., & Bessa, M. (2022). A survey of multisensory VR and AR applications for cultural heritage. Computers & Graphics, 102, 426–440. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo, M. (2019). Critical reflection, unlearning, and engagement. Management Learning, 50(4), 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGladdery, C. A., & Lubbe, B. A. (2017). Rethinking educational tourism: Proposing a new model and future directions. Tourism Review, 72(3), 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L., Yan, F., Fang, Q., & Si, W. (2024). Research on the educational tourism development of intangible cultural heritage: Suitability, spatial pattern, and obstacle factor. Sustainability, 16(11), 4647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, W. (2017). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. In The political nature of cultural heritage and tourism (pp. 469–490). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Orphanidou, Y., Efthymiou, L., & Panayiotou, G. (2024). Cultural heritage for sustainable education amidst digitalisation. Sustainability, 16(4), 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasaco-González, B. S., Campón-Cerro, A. M., Moreno-Lobato, A., & Sánchez-Vargas, E. (2023). The role of demographics and previous experience in tourists’ experiential perceptions. Sustainability, 15(4), 3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76(4), 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Pipitone, J. M. (2018). Place as pedagogy: Toward study abroad for social change. Journal of Experiential Education, 41(1), 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q., Zuo, Y., & Zhang, M. (2022). Intangible cultural heritage in tourism: Research review and investigation of future agenda. Land, 11(1), 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeh, S. (2022). Tourist’s segmentation based on culture as their primary motivation. Athens Journal of Tourism, 9(3), 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmanovic, E., Rizvic, S., Harvey, C., Boskovic, D., Hulusic, V., Chahin, M., & Sljivo, S. (2018). VR video storytelling for intangible cultural heritage preservation. The Eurographics Association. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D. (2018). Empathy and embodied experience in virtual environment: To what extent can virtual reality stimulate empathy and embodied experience? Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukri, S., Arshad, H., & Abidin, R. Z. (2017). The design guidelines of mobile augmented reality for tourism in Malaysia. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1891(1), 020026. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M., & Raposo, R. (2023, June 8–9). Designing a framework for rural community-based collaborative cultural mapping: The fontoura project. ICTR 2023 6th International Conference on Tourism Research, Pafos, Cyprus. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L., & Akagawa, N. (2009). Intangible heritage. Routledge London. [Google Scholar]

- Toker, B., & Rezapouraghdam, H. (2021). Intangible cultural heritage and management of educational tourism: An experiential learning approach. In Handbook of Research on Human Capital and People Management in the Tourism Industry (pp. 199–216). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- tom Dieck, M. C., & Jung, T. (2018a). A theoretical model of mobile augmented reality acceptance in urban heritage tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(2), 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- tom Dieck, M. C., Jung, T. H., & Rauschnabel, P. A. (2018b). Determining visitor engagement through augmented reality at science festivals: An experience economy perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 82, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- tom Dieck, M. C., Jung, T. H., & tom Dieck, D. (2018c). Enhancing art gallery visitors’ learning experience using wearable augmented reality: Generic learning outcomes perspective. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(17), 2014–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (1972). UNESCO world heritage centre—Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- UNESCO. (2003). Text of the convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage—UNESCO intangible cultural heritage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- UNESCO—about living heritage and education. (n.d.). Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/about-01159 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- VanVoorhis, C. W., & Morgan, B. L. (2007). Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 3(2), 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. (2022). The Application of Personalized Recommendation System in the Cross-Regional Promotion of Provincial Intangible Cultural Heritage. Advances in Multimedia, 2022(1), 5811341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Liu, Q., Wei, X., & Fan, M. (2025). Facilitating Daily Practice in Intangible Cultural Heritage through Virtual Reality: A Case Study of Traditional Chinese Flower Arrangement. arXiv, arXiv:2503.06122. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W. J., & Chiou, S. C. (2021). The safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage from the perspective of civic participation: The informal education of Chinese embroidery handicrafts. Sustainability, 13(9), 4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W., Lowell, V. L., & Yang, L. (2024). Developing English language learners’ speaking skills through applying a situated learning approach in VR-enhanced learning experiences. Virtual Reality, 28(4), 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yidan, H., Yip, J., & Theavar, V. (2025). Exploring the potential of mobile phone applications in the transmission of intangible cultural heritage among the younger generation. Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture, 54(1), 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. (2006). Zhongguo Tang san cai [Chinese Tang Sancai]. Shandong Meishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Y., Lan, T., Liu, S., & Zeng, H. (2024). The post-effects of the authenticity of rural intangible cultural heritage and tourists’ engagement. Behavioral Sciences, 14(4), 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scenario Type | Learning Task | Learning Behavior | Design Implementation | Learning Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity Scenario | Historical route exploration task | Challenge seeking | Themed route selection, point-based progression, task unlocking mechanism. | Motivation for exploration, acquisition of basic cultural knowledge. |

| Information Scenario | Cultural interpretation and feedback module | Critical reflection | Multimedia content (text, image, video), tourist comment interaction. | Deeper cultural understanding, attitudinal engagement. |

| Interaction Scenario | Simulation of Tang Sancai making | Immersive engagement | Step-based simulation of the Tang Sancai making process, glazing interaction, post-task sharing. | Procedural understanding and emotional engagement with Tang Sancai craftsmanship. |

| Constructs | Dimensions | Number of Items | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generic Learning Outcomes | Knowledge and Understanding (KU) | 4 | (Hooper-Greenhill, 2004); (tom Dieck et al., 2018c); (Li et al., 2022) |

| Enjoyment, Inspiration, and Creativity (EIC) | 4 | ||

| Skills (S) | 5 | ||

| Attitudes and Values (AV) | 3 | ||

| Action, Behavior, and Progression (ABP) | 3 | ||

| Technology Acceptance | Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 5 | (Davis, 1989); (de Oliveira Nunes & Mayer, 2014); (Hamouda, 2022) |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) | 4 |

| Item | Subtype | Experimental Group (n = 43) | Control Group (n = 41) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–30 | 17 (39.5%) | 16 (39%) |

| 31–45 | 14 (32.6%) | 14 (34.1%) | |

| 46–60 | 9 (20.9%) | 9 (22%) | |

| 61–70 | 3 (7.0%) | 2 (4.9%) | |

| Ethnicity | Han | 36 (83.7%) | 37 (90.2%) |

| Ethnic minorities | 7 (16.3%) | 4 (10%) | |

| Gender | Female | 21 (48.8%) | 19 (46.3%) |

| Male | 22 (51.2%) | 22 (53.7%) | |

| Highest Qualification | High School or below | 5 (11.6%) | 4 (9.8%) |

| Associate’s degree | 15 (34.9%) | 12 (29.3%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 20 (46.5%) | 22 (53.7%) | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 3 (7.0%) | 3(7.3%) | |

| Frequency of Tourism Application Use | Never | 7 (16.3%) | 5 (12.2%) |

| Rarely | 17 (39.5%) | 19 (46.3%) | |

| Sometimes | 14 (32.6%) | 13 (31.7%) | |

| Often | 5 (11.6%) | 4 (9.8%) |

| Question Type | Experimental Group (n = 43) | Control Group (n = 41) | t | Cohen’s d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Std. Error | M | SD | Std. Error | |||

| Retention | 32.65 | 6.32 | 0.96 | 28.54 | 8.03 | 1.25 | 2.6 * | 0.57 |

| Comprehension | 21.72 | 6.34 | 0.97 | 16.34 | 6.77 | 1.06 | 3.76 *** | 0.82 |

| Average score | 54.37 | 9.89 | 1.51 | 44.88 | 11.77 | 1.84 | 3.99 *** | 0.87 |

| Category | Experimental Group (n = 43) | Control Group (n = 41) | t | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| KU | 5.27 | 0.41 | 4.23 | 0.51 | 10.27 *** | 2.25 |

| EIC | 5.01 | 0.6 | 4.15 | 0.47 | 7.3 *** | 1.59 |

| S | 5.22 | 0.61 | 3.91 | 0.58 | 10.09 *** | 2.2 |

| AV | 4.63 | 0.6 | 4.17 | 0.67 | 3.28 ** | 0.72 |

| ABP | 4.41 | 0.61 | 4.31 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.16 |

| Category | Experimental Group (n = 43) | Control Group (n = 41) | t | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| PU | 5.9 | 0.66 | 4.81 | 0.84 | 6.55 *** | 1.44 |

| PEOU | 5.66 | 0.79 | 5.32 | 0.67 | 2.12 * | 0.46 |

| β | t | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PU | 0.677 | 9.10 *** | [0.529, 0.826] |

| PEOU | 0.225 | 3.02 ** | [0.077, 0.373] |

| R2 | 0.567 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Dolah, J. Mobile-Enhanced Outdoor Education for Tang Sancai Heritage Tourism: An Interactive Experiential Learning Approach. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 743. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060743

Wang J, Zhang X, Dolah J. Mobile-Enhanced Outdoor Education for Tang Sancai Heritage Tourism: An Interactive Experiential Learning Approach. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):743. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060743

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jing, Xing Zhang, and Jasni Dolah. 2025. "Mobile-Enhanced Outdoor Education for Tang Sancai Heritage Tourism: An Interactive Experiential Learning Approach" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 743. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060743

APA StyleWang, J., Zhang, X., & Dolah, J. (2025). Mobile-Enhanced Outdoor Education for Tang Sancai Heritage Tourism: An Interactive Experiential Learning Approach. Education Sciences, 15(6), 743. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060743