As seen in

Table 1, the participant group in this study consists of 30 individuals, predominantly female (

n = 18, 60%) compared to male participants (

n = 12, 40%). Participants are diverse in age, ranging from 22 to 46, with a notable concentration of those in their early 20s and 40s. Academic levels vary, with the majority pursuing doctoral degrees (

n = 18) and the remainder engaged in master’s studies (

n = 12). The study fields covered a broad spectrum, including Primary Education, English Language, History, Science, Mathematics, ICT, Geography, and Social Sciences. There is a higher proportion of students specializing in English Language and Primary Education, particularly at the Ph.D. level. This composition suggests a sample encompassing early-career and more mature students, possibly reflecting different educational or professional trajectories. The presence of both master’s and Ph.D. students may provide insights into other perspectives on academic and professional development within varied educational disciplines.

4.2.2. Findings

This section presents the findings from the participant’s responses to the semi-structured interview questions, followed by each result based on the responses of the thirty participants from the six research questions raised in this study. The respondents, who were current university graduate students, were presented with themes, sub-themes, and codes.

RQ1. How do you define the concept of digital governance? What prior knowledge do you have about digital governance?

Table 2 presents the views of graduate students regarding this question. It also gives the subthemes, codes, and number of participants created for the graduate students theme under this topic.

Table 2 reveals two main themes: the definition and scope of digital governance and awareness and familiarity with digital governance. Within the first theme, definition and scope of digital governance, 18 participants identified e-government as a key component, describing digital governance as using digital technologies in governance processes. Additionally, 12 participants mentioned that digital governance aims to enhance decision-making speed and efficiency through digital means. The second theme, awareness and familiarity with digital governance, indicates that 20 participants had no prior scientific knowledge of the concept and were unfamiliar with it. Seven participants expressed a basic understanding of digital governance and the digital tools and systems used in governance. In comparison, three participants noted that this interview was their first encounter with the concept. This data highlights varying levels of familiarity, suggesting a need for further education on digital governance in this demographic. Some participants in the research expressed their views as follows:

This is the first time I have encountered it (P2). I define it as ensuring digital networking within institutions (P16). I am unfamiliar with the concept (P28). From the name, I would guess that it refers to methods developed by the state to facilitate tasks in various institutions and save time by using information technology. Applications like e-government, MHRS, and e-nabız could be examples of this (P16).

Digital governance is how the public and private sectors utilize digital technologies to manage decision-making, service delivery, and interaction processes (P5). This concept emerges by integrating information technologies into governance processes, highlighting transparency, participation, efficiency, and accountability. It facilitates citizens’ access to public services through digital platforms. For instance, e-government applications and digital service portals are examples of such governance (P30).

RQ2. What role do you think digital governance plays in higher education institutions? What do you think about the contribution of digital tools to decision-making processes?

Table 3 presents the participants’ role in digital governance. These responses are grouped under three main themes.

Table 3 presents an analysis of the role of digital governance across three primary themes: digital data and information management, impact on efficiency and decision-making, and digital governance in institutions and networks. Digital data and information management is a central theme, focusing on how governance adapts to technological advancements. Managing and organizing digital data, such as photos, videos, and documents, and ensuring data are stored and classified effectively is essential for efficient governance, as emphasized by 28 participants. Additionally, 12 participants stated that data management practices within digital governance play an important role by promoting network-based organizational management, further supporting collaborative digital ecosystems. A total of 15 participants stated that digital tools also enhance transparency and accessibility in governance, streamlining decision-making processes, increasing management efficiency, saving time, and improving overall decision quality. Impact on efficiency and decision-making illustrates how digital governance empowers organizations to make more informed decisions by leveraging data-driven insights. A total of 10 participants defined data and analytics as enabling precise, evidence-based decision-making, improving outcomes, and responding to stakeholder needs effectively. Furthermore, digital tools support inclusive governance by democratizing decision-making processes. A total of 5 participants stated that this inclusivity broadens access to participation in governance, allowing diverse stakeholders to contribute to decision-making. Also, 23 participants stated that digital governance in institutions and networks highlights integrating digital technologies to enhance communication and coordination within and across organizations. By facilitating inter-network communication, digital governance enables institutions to manage processes more effectively, share information seamlessly, and collaborate across networks to address complex governance challenges. Some participants in the research expressed their views as follows:

There could be a possibility of making biased or unbiased decisions. For this reason, there should be proper and competent governance (P10). Digital governance plays an essential role in higher education institutions. Nowadays, many of our tasks are handled through digital platforms. In this sense, coordination between students and teachers can be highly effective (P28).

It saves time, helps make more accurate decisions, and supports more confident decision-making processes (P23). The use of digital resources provides savings in both time and space. I think it is possible for groups of people who cannot meet in person to come together using digital tools, and online tools can be used to manage and track tasks. This shows that participants can join the process from wherever they are, which provides a significant advantage for both managers (P13).

RQ3. Do you think universities are sufficient in digital governance? How can digital governance processes be used more effectively?

Table 4 presents the effectiveness of digital governance. These responses are grouped under three main themes.

Table 4 reveals key challenges and needs in the digital governance of higher education institutions, highlighting three critical areas. First, there is an urgent need for increased investments to address inadequate infrastructure, limited internet access, and insufficient technological resources, which 26 participants emphasized. These deficiencies are further exacerbated by disparities in digital governance across universities, leading to unequal access and implementation. Second, the training, awareness, and capacity-building theme underscores the necessity of equipping faculty, staff, and students with the digital skills required to use modern tools effectively. However, uneven digital governance across institutions remains a barrier to widespread adoption and skill enhancement, a concern of 19 participants. Finally, technological integration and the use of digital tools demand strategic improvements, such as enhanced data management and interdisciplinary collaboration. This theme, highlighted by 15 participants, stresses the importance of coordinated planning and partnerships among universities to ensure the effective use of digital technologies. Addressing these interconnected challenges is essential for fostering equitable and efficient digital governance in higher education. Some participants in the research expressed their views as follows:

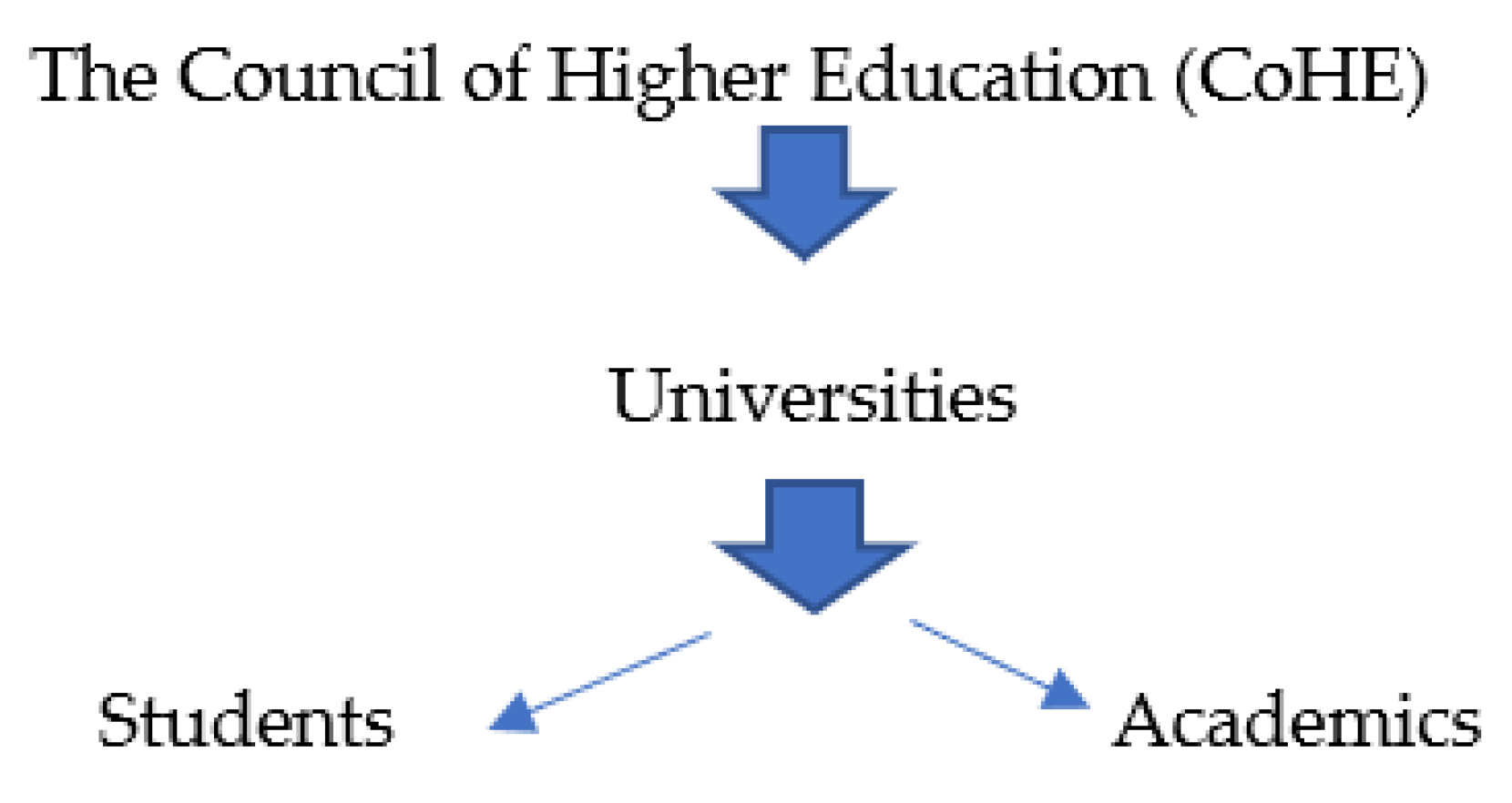

Universities have great potential in digital governance, but in general, they have not yet fully realized this potential. While some universities have made significant progress in digital transformation processes, many higher education institutions face challenges in using digital governance tools more comprehensively and effectively (P9). To use digital governance processes more effectively, universities should increase infrastructure investments, develop digital awareness, and adopt data-driven decision-making processes. Additionally, involving students and academics more through participatory and transparent digital governance models can make the university’s digital transformation more inclusive. This way, universities can increase their academic and administrative performance and contribute more to society (P17).

No, it is insufficient because I think there is a lack of internet and adequate cognitive and technological infrastructure (P3). Compared to other countries, more extensive and accessible research can be conducted (P6). It needs further development. Interaction should be increased (P17). I think it could be better (P5). No, it is not sufficient. The necessary infrastructure work, training, and in-service education can make it more effective (11). I think more education and opportunities could be provided, but I do not think it is sufficient (14).

RQ4. How do you think your master’s and doctoral education developed your digital governance awareness or knowledge?

Table 5 presents the awareness of digital governance. These responses are grouped under three main themes.

Table 5 reveals significant insights into digital governance’s practical application and benefits in higher education, emphasizing its transformative potential in three key areas. First, the use of digital platforms in education, highlighted by 24 participants, demonstrates how digital governance enhances the efficient management of educational resources and administrative tasks, streamlining operations across institutions. Second, the benefits of digital governance in the academic environment, identified by 21 participants, include improved accessibility to information and academic resources, which saves time and boosts overall efficiency in academic processes. Finally, the development of research and access skills, emphasized by 18 participants, underscores the role of digital tools in advancing research quality by enabling better data management and access to essential resources. Together, these findings highlight the multifaceted value of digital governance in fostering efficiency, accessibility, and innovation within the academic landscape. Some participants in the research expressed their views as follows:

Since I am in the early stages of my master’s program, I have not yet gained significant awareness (P1). I do not think it has changed much (P12). The more research we do on the literature, the more it positively impacts our knowledge base (P23). Mainly in literature reviews, using many applications has contributed significantly to my development. I have greatly benefited from digital tools in my research during this process. They help me achieve results and increase my knowledge (P8).

Due to my work in the field and teaching, I effectively use web tools. I do not think my master’s and doctoral studies have contributed significantly to this process, but tools like Microsoft Teams are essential for tracking it and improving speed (P6). As a master’s student, my professors can provide us with the course schedule, resources, and guidance on becoming more successful through digital communication (P27). A considerable library now fits into a small computer, making accessing information and management easier. For example, it was tough to reach a dean or rector physically, but thanks to digital governance, I can now be just an email away. The same applies to the government; for instance, with CİMER, you can reach even the highest authorities (P30).

RQ5. What skills and competencies should be offered to students or academics regarding digital governance? Were these skills sufficiently imparted during your education?

Table 6 presents the skills of digital governance. These responses are grouped under three main themes.

Table 6 reveals the essential skills and challenges associated with digital governance in higher education, focusing on the perspectives of students and academics. The most critical theme, identified by 30 participants, underscores the importance of digital literacy, particularly skills related to analyzing data and making informed decisions, a cornerstone of effective digital governance. Furthermore, 28 participants emphasized the positive impact of education in equipping them with valuable digital governance skills, indicating that formal education has played a significant role in fostering these competencies. However, challenges persist, as highlighted by 26 participants, who noted barriers such as insufficient infrastructure and the limited integration of digital tools within the education system. These shortcomings have forced some individuals to acquire digital governance skills independently or through non-formal means. Addressing these gaps in infrastructure and curriculum integration is vital to ensuring that all students and academics are adequately prepared for the demands of digital governance. Some participants in the research expressed their views as follows:

Training on this topic can be provided (P8). It was not imparted. If it had been imparted, I would have learned it myself (P19). Competencies suitable for the current era should be imparted (P16). More training and seminars should be held. However, the most important thing is to create a solid digital infrastructure. I do not think it contributed much to me during my education (P10). I think there should be training sessions with helpful information from competent people to help us manage the process better. We should receive training on practical activities to apply and use in the process (P22).

Data analysis, digital communication, project management, cybersecurity, and critical thinking skills should be developed. I will gain these skills in my ongoing education (P27). Most importantly, reaching the most distant individual or information or managing an organization significantly benefits students and academics. Of course, some skills have been gained (P28). Academics and students should be able to effectively use digital tools, translate their knowledge into practice, and understand cybersecurity. They should also be able to communicate and interact with other stakeholders, so their social skills and sense of responsibility are also necessary. Some courses in my doctoral education increased my awareness and achievements in this area (P12).

RQ6. What are the biggest challenges encountered in digital governance processes, and what are your suggestions for overcoming these challenges? Additionally, what opportunities do you think digital governance provides, and how does it benefit in terms of efficiency and inclusivity?

Table 7 presents the opportunities and challenges of digital governance. These responses are grouped under four main themes.

Table 7 comprehensively analyzes digital governance’s challenges, opportunities, and benefits in higher education. The most pressing challenges, noted by 30 participants, include a lack of formal education in digital governance, inadequate knowledge and skills, infrastructure deficiencies, limited access to technology, cybersecurity concerns, resource insufficiencies, and resistance to change. Addressing these barriers requires a multifaceted approach, as highlighted by 27 participants, who emphasized the importance of service-based education, including targeted training programs, technological investments, strategic infrastructure planning, and awareness initiatives to foster open communication and adaptability. On the positive side, opportunities in digital governance, recognized by 28 participants, include enhanced efficiency, inclusivity, transparency in decision-making, and the provision of personalized and accessible educational services. Furthermore, the benefits of efficiency and inclusivity, identified by 30 participants, demonstrate how digital governance facilitates faster access to information, empowers individuals through digital tools, supports disadvantaged groups, and enables effective remote management. Together, these findings highlight the transformative potential of digital governance while emphasizing the need for strategic action to overcome challenges and maximize its benefits. Some participants in the research expressed their views as follows:

Challenges in digital governance processes may include cost insufficiency and lack of hardware (P1). The biggest challenge is insufficient knowledge, and expanding inclusivity while increasing efficiency is crucial (P10). Limited access to the internet and network administrators are restrictive factors. The opportunities include efficiently conducting research and acquiring competencies in digital environments. In terms of efficiency, it will positively affect the reliability and scope of research (P3). With the internet going down and not always having devices available to access, aside from a phone, we can search and get help on any topic we need (P15).

Lack of knowledge leads to an inability to use digital tools effectively. Digital tools can simplify our lives in many ways (P12). Infrastructure problems and various restrictions limit access to information. However, this allows us to finish our work more quickly and easily (P5). Security concerns, lack of self-efficacy, and resource insufficiency are challenges (P14). The biggest problem is the lack of internet resources, especially for people living in remote areas like villages. The second most significant issue is the inadequate use of technology. Unfortunately, there are still severe deficiencies in this regard. As for the benefits, I think it is essential because it allows access from anywhere and under any condition, enables remote management of processes, and increases the efficiency of these processes (P9).