Abstract

An increased focus on research with rather than on or of participants provides challenges with the implementation of such research with children. This extends to participatory practices in which co-design is implemented towards developing a technology-based product or solving a problem particularly in the domain of health literacy. This systematic scoping review aimed to examine the practices of co-design with children to inform an interdisciplinary research team as they embarked on the development of a digital health literacy tool for young learners. While there were limited sources identified in the review (n = 11), it was ascertained the process of co-design is not clearly understood by all, and most research described implementation with older children or youth. A range of methods for co-design were identified, and the importance of an interdisciplinary approach was highlighted. Based on these findings, recommendations are made for successful co-design with young children towards digital products or solutions to problems that can be applied in health and other fields.

1. Introduction

This paper outlines the process and results of a systematic review of the co-design of health-literacy-related tools with children. The review aimed to identify components of successful co-design with children in the development of health-related tools to inform a project to develop a health-literacy-focused digital tool for young children. The review was completed as part of the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child (CEDC) with a team that included researchers from the Health and Education disciplines within one University.

Co-design is considered to be a collaborative, participatory approach to designing solutions that aim for more relevant and effective outcomes. Previous research emphasises the importance of involving all stakeholders and potential users as collaborators in the development of a product or solution (Bevan Jones et al., 2020). The active involvement of all users at all stages, especially in digital design, ensures the end product meets the user requirements (McKenney & Reeves, 2018). When working with children in education and health, stakeholders include children, their families, service practitioners/content experts, and digital technology designers/programmers. Co-design has increasingly been used with children and young people in various stages of the design process (Hansen, 2017) and is recognised as a way of presenting young people’s perspectives. Users bring a deep understanding of their context, needs, and opportunities, which are explored as part of the co-design process (Treasure-Jones & Joynes, 2018). While the focus of this paper is on health-related tools, the findings may be applicable more broadly.

When co-designing with children or young people on health-related digital tools in diverse settings, the process may be impacted by

- The researcher who wants to investigate an idea or construct;

- The educator/practitioner who might be engaged in using the co-designed product in their setting;

- The tool developer who brings the coding skills and development knowledge to the process to transform the ideas and wants of the other stakeholders into a working product;

- The children whose voice, ideas, and current understanding of how digital technology works and who are critical as the ‘end user’ to the process and outcome.

Not all activities marked in previous health-literacy-related research as co-design are such, with many studies falling short of implementing what could be considered an authentic co-design process. If meaningful co-design is to be realised within the health domain, it is important to find ways for children to actively participate as co-designers alongside adults in all stages of the process. Bringing children’s perspectives into design research acknowledges their right to participate in decisions that affect them, as outlined in Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1989). Children are important users of digital applications [apps] in health and other contexts, and their experiences and thoughts have been shown to be valuable in the co-design process to ensure the end product fits their needs (Druin, 2002). This scoping review was undertaken to identify any gaps in the literature and make recommendations for future co-design of health-related tools with children, including the co-design of digital applications. While the papers examined draw from a health focus, the ideas may also be applicable across other disciplines.

Digital application development defines the process of creating apps for solutions that leverage digital technologies to fulfil specific purposes or address particular business needs (Kissflow, 2024). Moreno et al. (2018) highlight that mobile technology creates new horizons for children with many digital applications created to engage children in fun games with educational benefits which may support behaviourist, constructive, situated, collaborative, informal, and lifelong learning (Naismith et al., 2004). For children to be fully engaged in all components of design research, they need to understand the research purpose, data collection techniques, and their role (ARC Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child [CEDC], 2024). Adopting a rights-based approach affords the consideration of children’s views of what changes they would like to see to enhance their experiences and uphold their rights in the digital world (Pothong & Livingstone, 2023).

2. Methodology

A transdisciplinary team within the CEDC was interested in co-designing a digital tool with early childhood educators and young children to increase knowledge of health-literacy-related topics. To begin this process, it was first important to develop a shared understanding of what co-design is in this context based on previous research. A scoping review was undertaken to investigate the question: How has a co-design process been implemented with children in previous research? This type of review was chosen as it can “identify gaps in the literature, determine the nature of the evidence, and then make recommendations for future primary research” (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2008, cited in Beynon & Straker, 2022, p. 8). The scoping review does not aim to examine all the available literature but rather to ‘scope out’ what is available within a specific search framework. As this project was focused on both the Health and Education disciplines, a review across these disciplines was selected to provide an overall summary of results but without the complexity of meta-analysis or a more complex examination of research quality (Peters et al., 2020).

Identification of Relevant Studies

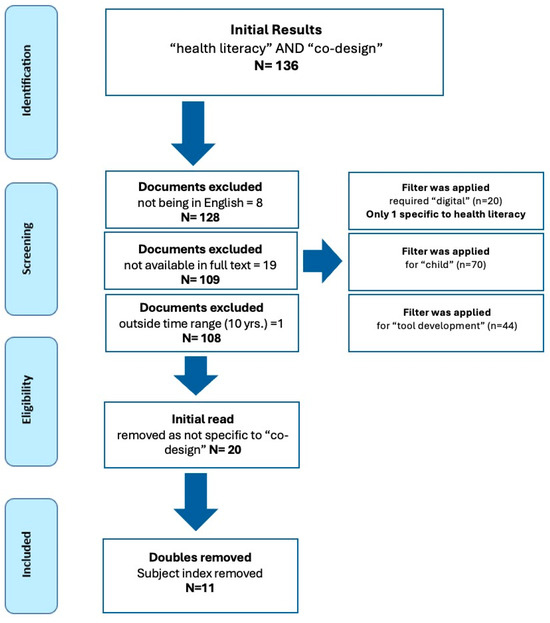

The goal of this scoping review was to develop a baseline knowledge of the research literature surrounding health-focused co-design processes with young children, identify any gaps in the literature, and make recommendations for future co-design research with children. A protocol was developed following the Arksey and O’Malley (2005) framework (see Figure 1), which includes

Figure 1.

Paper identification process.

- 1.

- Identifying the research question. How has a co-design process been implemented with children in previous research? To assist in answering this, two subsidiary questions were formulated:

- What is the extent, range, and nature of research and publication activity addressing co-design with children in the education and health literature?

- What are the current gaps in knowledge and research priorities about co-designing with children in the education and health literature?

- 2.

- Identifying relevant studies. Eligibility criteria for articles were:

- Published in the last 10 years;

- Published in English;

- Peer reviewed;

- With children aged birthto 8 years;

- Available in full text.

The databases searched included ProQuest Central, SAGE Journals, Taylor and Francis Journals, ERIC, Informit A+ Education, and Informit Health Collection. These sources were chosen as being reputable sources within the Health and Education disciplines, thus providing a cross-section of the literature to enable summaries to be developed and the research questions to be explored. The search terms were health literacy AND co-design. These terms were chosen to ensure results that directly related to the research question, while also being specific to the area of health research to keep the task manageable within the timeframe. - 3.

- Study selection. From the initial database search, 136 papers were identified. When the English criteria were applied, the number was reduced to 128, requiring full text reduced the number to 109, and the last ten years reduced this to 108. To be more specific to the question of this review, the search term ‘digital’, the term ‘child’, and the term ‘tool development’ were then added to the filtering process. This resulted in a further 38 papers being removed as they did not include children and a further 26 as they were not directly related to tool development. This reduced the number to 45. After the researchers’ initial reading of the 45 abstracts of these papers a further 24 were removed as they were not specifically connected to co-design in terms of having different cohorts of stakeholders work together on the development of an intervention or tool. Doubles, a subject index, and an abstract for a poster were also removed, leaving the final number of articles at 11. Full details of the papers are included in Table 1.While it is recognised that the use of ‘health literacy’ in the initial search may have excluded other co-design papers, the scoping focus was important as a first stage of a larger research project. Although the examples given relate to health-focused problems, the tenets of the co-design process may have wider applications in other disciplines.

- 4.

- Charting the data. The data were charted by two of the authors as this is a useful way of sifting, sorting, and mapping key ideas, themes, and information. The following headings were used in this process: year of publication, title, author/s, location of the study and sample size, research aims/questions, theoretical perspective, methodology/data analysis plan, and findings/implications. Once the 11 papers were identified and charted, the publications were divided among the researchers with each paper to be read in full by two authors to ensure that personal bias and opinions were eliminated. The reviewers then completed the table with all relevant information (see Table 1).

- 5.

- Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. Three of the authors then met to complete the thematic analysis based on the two reviewers’ synthesis of the papers. The thematic analysis of the key findings involved the process of analysing the data to look for “commonalities, relationships and differences” across the publications in relation to the research question (Gibson & Brown, 2011, p. 127). The trio examined Table 1 in relation to the research questions, as well as creating a code that best reflected the text. A preliminary codebook was created and modified continually by the team engaged in the data analysis, which resulted in a high level of agreement among the researchers. Any differences in opinion were reconciled by discussion of the evidence from the papers, and a group consensus was reached. This inductive process led to the identification of three specific themes within which to categorise the 11 papers: socio-cultural elements, modes or methods of engaging children, and the transdisciplinary nature of the co-design process.

Table 1.

Full details of the papers.

Table 1.

Full details of the papers.

| Year | Title | Author/s | Location of the Study/Sample | Research Aims/ Questions | Theoretical Perspective | Methodology/Data Analysis Plan | Key Findings and Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Long-term LEGO therapy with humanoid robot for children with ASD | Barakova, E.I., Bajracharya, P., Willemsen, M., Lourens, T., & Huskens, B. | Netherlands 6 boys aged 8–12 years who were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | To determine how children interact with a robot in training/learning situations | Experimental design | Use of a robot to guide LEGO training/building, co-design process Data analysis: clinical and HRI-trained observers analysed children’s behaviour and reactions in recorded experiments | ASD children with a therapist gain different value from having a robot mediate; essentially, the robot adds value to sessions Use of a participatory design Testing phase only Multiple stakeholders Transdisciplinary approach |

| 2020 | Practitioner review: Co-design of digital mental health technologies with children and young people | Bevan Jones, R., Stallard, P., Agha, S. S., Rice, S., Werner-Seidler, A., Stasiak, K., Kahn, J., Simpson, S. A., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Rice, F., Evans, R., & Merry, S | Wales, UK 25 original articles and 30 digital mental health technologies | Provide a practitioner review of the literature on the approaches to the design and development of digital mental health technologies in collaboration with children, young people, and other stakeholders. Map the existing evidence and practice for the co-design with children and young people. Use case studies and exemplars to illustrate key points throughout. | Intervention development and review | Literature review of papers from across Medline, PsycInfo, and Web of Science databases, as well as guidelines, reviews, and reference lists | The following key recurring themes related to the co-design process were identified: (a) the principles of co-design, including the participants/stakeholders and stages of involvement; (b) the potential methods and techniques of involving and engaging CYP; (c) co-designing the initial prototype, considering the diversity in the user group; and (d) the potential challenges of co-design with CYP, including its evaluation. Co-design involves all relevant stakeholders throughout the life and research cycle of the programme. This review helps to inform practitioners and researchers interested in the development of digital health technologies for children and young people. Multiple stakeholders Transdisciplinary approach |

| 2015 | Teachers as Co-Designers of Technology-Rich Learning Activities for Early Literacy | Cviko, A., McKenney, S., & Voogt. J. | Netherlands; 5 teachers and 2 interns (student teachers) and 111 children from 11 class twos in 4 schools in the Netherlands | To understand how the co-designer role contributes to technology integration in kindergarten classes and how that influences learning, teachers formed two teams to design curriculum and activities; perceptions and experiences were recorded along with student outcomes | Participatory co-design | Case study method (with control group) using PictoPal, a technology-supported intervention for early literacy; quasi-experimental design: interviews, process notes in design meetings; data analysis: summarise interview responses + ANOVA (analysis of variance) + ANCOVA (covariance) + paired sample t-test | Teacher perceptions of the appropriateness of curricular activities for their teaching/classrooms are crucial for implementation and positive pupil learning outcomes to be effective. Testing phase only Multiple stakeholders Transdisciplinary approach |

| 2020 | Engaging early childhood teachers in participatory co-design workshops to educate young children about bullying | Ey, L-A., & Spears, B. | Australia 12 South Australian EC teachers from 25 schools 99 child responses post-intervention | Develop a unique bullying prevention programme co-designed in the school context in response to children’s understanding of bullying. | Participatory co-design framework | Mixed method, quasi-experimental design: participatory co-design framework with multiple phases: small group interviews, discussion, Q sort (visual elicitation cartoon methodology). Triangulation of data, inductive thematic analysis using a priori and emerging themes; test–retest experimental design/evaluation framework | Successfully established a PD framework that is empowering and easy to use. Testing phase only Multiple stakeholders |

| 2021 | Annual Research Review: Immersive virtual reality and digital applied gaming interventions for the treatment of mental health problems in children and young people: The need for rigorous treatment development and clinical evaluation. | Halldorsson, B., Hill, C., Waite, P., Partridge, K., Freeman, D., & Creswell, C. | England UK 19 studies were identified that examined 9 applied games and 2 VR applications | This systematic review aims to identify and synthesize current data on the experience and effectiveness of applied games and VR for targeting mental health problems in children and young people (defined as average age of 18 years or below). | Intervention development and review | Systematic literature review: Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Web of Science. | Despite the enthusiasm for applied games and VR, existing interventions are limited in number and evidence of efficacy, and there is a clear need for further co-design, development, and evaluation of applied games and VR before they are routinely offered as treatments for children and young people with mental health problems. |

| 2020 | Co-Designing a New Educational Tablet App for Preschoolers | Hoareau, L., Tazouti, Y., Dinet, J., Thomas, A., Luxembourger, C., Hubert, B., Fischer, J-P., & Jarlegan, A. | France 10 educators, university research team; 1 teacher tested app with a group of 4 kindergarten children (boys and girls) aged between 4 and 5 years | Development of an early literacy/early numeracy educational app: collaboration between researchers, practitioners, and designers (and children) | Child-centred pedagogy | Co-design process of app in multiple phases—esearch, co-design, and software development phases—uses Kucirkova’s (2017) iRPD framework | Process was effective, formation of a multi-disciplinary team was key, use of framework was also key in guiding the process with successful creation of educational app Testing phase only Multiple stakeholders Transdisciplinary approach |

| 2021 | Making of Mobile SunSmart: Co-designing a Just-in-Time Sun Protection Intervention for Children and Parents | Huh, J., Lee, K.J., Roldan. W., Castro, Y., Kshirsagar, S., Rastogi, P., Kim. I., Miller, K.A., Cockburn, M., & Yip, J. | California USA Design-domain experts; children subject domain experts (25) and their caretakers (29); KidsTeam UW 11–12 children (8–12 years of age) and 22–48 parents Note: KidsTeam UW is an ongoing inter-generational co-design group at the University of Washington. | To develop a technology-based intervention for sun protection for children and their parents. | Participatory design method | Iterative co-design process with design expert KidsTeamUW children and subject expert children and their parents. Data analysis: inductive methods and deductively compared emerging themes. | Three themes emerged: (1) preference for non-linear educational format with less structure, (2) situations not conducive to prioritizing sun protection, (3) challenges, barriers, and ambiguity relating to sun protection to protect oneself and one’s family. Based on design ideas/iterative participant feedback, three modules were developed: personalized and interactive data intake, narrative education with augmented reality experiment, and person/real-time-tailored JITAI assessment. Recognition of children’s rights in research Use of a participatory design Collecting student’s voice Multiple stakeholders Transdisciplinary approach |

| 2020 | Communicating Handwashing to Children, as Told by Children | Rutter, S., Stones, C., & Macduff, C. | England, UK, 79 children aged 6–11 years | To determine which types of messages were most effective in communicating the importance of handwashing to children | Evaluative study | In co-design process, children undertook three activities: they evaluated messages about handwashing (selected by authors), generated messages, and refined key messages. | Children found specific types of messages more effective, particularly reminders and encouragement, and education and information messages, but not messages that focused on social norms or time-related messages (e.g., handwashing is quick) Collecting student’s voice |

| 2018 | Participatory design of health care technology with children | Sims, T. | Brighton, UK Examined frameworks/methods involving children in design of health care technologies | Discussed various methods of child participation in design of health care technologies (such as prosthetics) | Socio-cultural approach | Examined CCI; ID; CI and socio-cultural approaches: Applying BRIDGE’s key tenets | Concluded the BRIDGE method, a socio-cultural approach involving children in design would provide a successful implementation in the design of prosthetics Recognition of children’s rights in research Use of a participatory design Multiple stakeholders Transdisciplinary approach |

| 2017 | Designing The “Next” Smart Objects Together With Children | Uğur Yavuz, S., Bonetti, R., & Cohen, N. | Italy 24 children aged 7–8 years | To highlight how children’s design provides inspiration for development of products | Vygotsky (2004) play settings. Design fiction using narrative techniques and imagination of children as source | Children guided through four stages of process to design ‘smart’ objects that interact/respond to human activity | Storytelling sessions and gameplay are useful processes in encouraging creative thinking and design Recognition of children’s rights in research Use of a participatory design Collecting student’s voice |

| 2021 | Children’s perspectives on emotions informing a child-reported screening instrument. | Zieschank, K. L., Machin, T., Day, J., Ireland, M. J., & March, S | Australia 20 children aged 5–11 years | First step in co-designing digitally animated assessment items for a new self-reported screening instrument for children: The Interactive Child Distress Screener (ICDS). Identify the animated items for the tool. | Intervention development and review | Semi-structured small group interviews | Identified the importance of audio-visual depictions of EBCs over written text. |

3. Results

3.1. Nature and Extent of Papers

In terms of overall demographics and structure of the 11 reviewed papers, they came from eight countries, including four from the United Kingdom, specifically, England (n = 3) and Wales (n = 1); four from Europe, i.e., the Netherlands (n = 2), Italy (n = 1), and France (n = 1); two from Australia; and one from the United States. All papers utilised qualitative research approaches, including iterative co-design processes (n = 8), literature reviews (n = 2), and interviews (n = 3). Given multiple strategies were used within some of these co-design studies, the total number of strategies was 13. A total of four of the 11 articles were published in 2020, with another two in 2021 and 2015, and one each in 2017, 2018, and 2019.

Of the 11 articles reviewed, 6 directly used co-design with children to develop digital technologies (Barakova et al., 2015; Huh et al., 2021; Rutter et al., 2020; Sims, 2018; Uğur Yavuz et al., 2017; Zieschank et al., 2021) and 2 literature reviews articulated the benefits of co-designing with children (Halldorsson et al., 2021; Bevan Jones et al., 2020). The remaining three articles (Cviko et al., 2015; Ey & Spears, 2020; Hoareau et al., 2020) referred to co-design in relation to children; however, the focus was on the process with teachers, parents, and/or colleagues.

3.2. Main Themes of Findings from Reviewed Papers

As outlined in Step 5 in the methods section, there were 3 main themes identified through the analysis across the 11 articles (see Table 2), which are discussed in the following sections of this paper:

Table 2.

Themes and number of papers within each for analysis.

- (1)

- The socio-cultural elements of effective co-design processes;

- (2)

- The various modes or methods used when engaging children in the co-design process;

- (3)

- The transdisciplinary nature of co-design processes.

Once again, it is important to iterate that these themes and the papers identified focused on health literacy tool development and, as such, do not represent a comprehensive overview of co-design outside of this focus. The authors do believe, however, that these findings may also prove useful in alternate contexts.

3.3. Socio-Cultural Elements of Effective Co-Design Processes

Papers that viewed children as competent and a necessary part of participatory design processes reflected a socio-cultural approach as essential to a co-design process. Socio-cultural theory developed from Vygotsky’s work suggests that human learning is a social process where cognitive development is based on interactions with others who are more skilled (Vygotskiĭ & Cole, 1978). Importantly, this approach views children as cognitively competent (James & Prout, 2015). A socio-cultural approach to research values the experiences, influences, and culture of each individual. Sims (2018) describes a socio-cultural approach to the design of a product that views children as active participants, contributing to the design process.

For some researchers, the socio-cultural elements of effective co-design include recognition of children’s rights in research that affects them, as well as the use of a participatory design approach to reflect this (Huh et al., 2021; Sims, 2018; Uğur Yavuz et al., 2017). Sims (2018) described the importance of recognising children’s rights in research, which has led to a considerable increase in their involvement in investigations. There has been increased use of methods, such as observation and conversation (Sims, 2018), creating collages (Huh et al., 2021), or storytelling methods (Uğur Yavuz et al., 2017) that enable children to express their views and opinions more fully when developing technologies. Huh et al. (2021) adhered to the philosophy of cooperative inquiry, where children and adults work together as equal and equitable partners. They acknowledged that research relationships between adults and children take time to build before children feel comfortable to contribute, so providing a safe space should be considered (Huh et al., 2021). Uğur Yavuz et al. (2017) and Sims (2018) were the only articles that specifically mentioned the importance of ‘children’s voices’ in the research and that children should be viewed as ‘design partners’. This focus on children’s agency (i.e., “the will and ability to positively influence their own lives and the world around them”; OECD, 2019, p. 2) and their engagement in research are key characteristics of participatory research from which co-design has developed.

Children commonly have roles in design research as user, tester, informant, and design partner; however, Iversen et al. (2017) introduced a role that empowers the child further—that of a protagonist. This role of protagonist encourages reflection and for the children to be the main agents driving the design process. The role of the protagonist also recognises children as having rights and, therefore, possess the competence to make decisions about their own learning (Hansen, 2017).

Bevan Jones et al. (2020) describe co-design as originating in the field of participatory research where the emphasis is on researching ‘with’ rather than ‘on’. This type of research emphasises the involvement of all stakeholders (including teachers, children, parents, and designers) as active collaborators in the development of a product. Of the eleven articles reviewed, five explicitly mentioned the use of participatory research (Barakova et al., 2015; Huh et al., 2021; Sims, 2018; Uğur Yavuz et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2021). To improve health, Barakova et al. (2015) co-designed Lego therapy for children on the Autism spectrum using a humanoid robot, and Huh et al. (2021) co-designed sun protection posters with children.

Sims (2018) co-designed upper limb prostheses with children but was also alert to how children were being asked to participate in co-design. She applied the BRuger Involving i Design, GEntænkt (English translation: User Involvement in Design, Revised–BRIDGE) model in an effort to minimize power positions when asking questions of children. Sims (2018) describes how the BRIDGE method is an iterative design process where children’s ideas for product development are sought through conversational methods such as focus groups. The model is underpinned by a socio-cultural theory of design, where end users, such as children, are viewed as cognitively capable of understanding their situation and, therefore, contributing special knowledge from their own world, which may be unknown to the designer. Once prototypes are developed by the designer, children provide feedback in iterative cycles of development. In the BRIDGE method, children are viewed as experts in their own lives with their expertise and decisions viewed as equal to any adult. In Sims’ (2018) study, children were involved in idea generation and device development before parents and professionals to respect children’s rights to share their views and have them valued. Additionally, child assent was treated as changeable, allowing children the right to choose their participation throughout the project.

Uğur Yavuz et al. (2017) used co-design workshops with children in which methods of storytelling techniques stimulated children to freely express their ideas about smart objects to create stories. Zheng et al. (2021) used a co-design process with specialist dietitians to develop and deliver the concept of an interactive medication label. This process used sketches, storyboards, and personas to develop a digital prototype of an interactive medication label. In this process, children’s input was gathered as the end users to provide the child patients with essential medical guidance and education to manage their own Cystic Fibrosis.

3.4. Modes or Methods Used When Engaging Children in the Co-Design Process

Research with children is complex (Lane et al., 2019), and so the methods of data collection in traditional research methodologies may be less applicable to children, especially those under eight years of age. Three of the publications reviewed for this manuscript (Bevan Jones et al., 2020; Halldorsson et al., 2021; Rutter et al., 2020) described the paucity of the literature on co-design research involving young children, with limited reporting on methods used or their success. A review by Bevan Jones et al. (2020) found 97% of the studies developed technologies for adolescents with only five targeting children under 12 years of age. They identified that co-design tends to occur in the early stages of a co-design project and that there was a lack of suitable methods of involvement for very young children in codesign research for technologies.

Of the 11 articles reviewed in this research, there was a wide range of methodologies implemented in the research design, including focus groups, interviews, workshops, and surveys or questionnaires. Four articles focused on the design process between adults (e.g., researchers, clinicians, teachers, and software engineers), with the involvement of the children only in the phase of testing what was designed (Barakova et al., 2015; Cviko et al., 2015; Ey & Spears, 2020; Hoareau et al., 2020). While these could still be considered co-design in the sharing of ideas by adults, the methods did not engage children through the whole process. This meant they were not authentically co-designed with children but rather for them.

Among a further four articles co-designed with, rather than on or for, children three specifically used student voice in their methodology by embracing the expert knowledge of children between the ages of 5 and 12 years (Huh et al., 2021; Rutter et al., 2020; Uğur Yavuz et al., 2017; Zieschank et al., 2021). These four co-design projects also utilised a range of methods, including working with children to solve a design problem as well as participation in iterative cycles of testing. Specifically, refinement of the mobile sun protection intervention (Huh et al., 2021); co-designing hand-washing posters and testing the resulting benefits in situ (Rutter et al., 2020); storytelling techniques to stimulate novel ideas for smart objects (Uğur Yavuz et al., 2017); and semi-structured interviews about contrasting emotional and behavioural constructs in the development of animated items in a screening tool (Zieschank et al., 2021).

In the final paper within this theme, Sims (2018) outlined the BRIDGE approach (discussed previously). They recommend the use of focus groups to reduce potential power differences and semi-structured interviews, which provide children with some guidance on what to talk about. During data collection, Sims (2018) provided art materials for children during the focus groups to represent their views alongside their verbal contribution. Finally, Hansen (2017) identifies the importance of partnership approaches between the designer and user to co-design as this relies on input from multiple stakeholders who each bring their own lens to the project, thus making the co-design process transdisciplinary.

3.5. Transdisciplinary Nature of Co-Design Processes

Bevan Jones et al.’s (2020) review of the literature identified the inclusion of multiple perspectives in a research partnership, signalling its importance in co-design processes. They identified the need to capture the diversity of researcher and user preferences with groups that are often made up of people across disciplines. Traditionally, co-design includes a researcher with the concept or idea, the technological developer who develops the tool to the required specifications, and often the end-user or focus group to test the models. This transdisciplinary team brings together multiple perspectives and is important in the successful implementation of co-design; however, not all stakeholders are included at all stages.

Across the 11 papers discussed here, seven referred in some way to multiple stakeholders, and six specifically to a transdisciplinary approach to co-design. These papers explored the roles of different stakeholders in the co-design process and the need for end-users to be engaged in the process from the initial stages of co-design. Specifically, several referred to the processes of co-design research through informant design and co-operative inquiry (Sims, 2018) or the participatory co-design process (Ey & Spears, 2020; Huh et al., 2021) to ensure research with stakeholders (Bevan Jones et al., 2020; Huh et al., 2021). It was, however, the engagement of the participants in relation to whom and how they were engaged that highlighted the transdisciplinary collaboration required in effective co-design and research related to this process. This type of research and co-design emphasises the involvement of all stakeholders as active collaborators in the development of a product (Bevan Jones et al., 2020), and this should be implemented with everyone being on an equal footing in the process rather than any one group is seen as more or less important (Sims, 2018).

Hoareau et al. (2020) argue that many educational apps are not adopted by teachers as they do not suit the educational environment. Specifically, they developed a three-way collaboration process of research, practitioner consultation, and then design with a research team, teachers in classrooms, and the app developers. While children were not directly involved in this co-design process, they were engaged in testing the developed app, and the teachers were able to provide feedback on this. Cviko et al. (2015) also viewed the engagement of teachers as important. They identified that teacher perceptions of technology in general, as well as specific apps, are critical in recognising if the technology/app would be successful in practice.

In a just-in-time intervention approach, Huh et al. (2021) used co-design with children and parents to develop a technology-based intervention for sun protection. They utilised diverse stakeholders, including health experts, parents, and children, identifying specific roles within these groups. They included a “design domain” that focused on technology and usability elements of the design and a “subject domain” that provided the subject and contextual knowledge showcased within the process. This shared approach of experts across disciplines was also embedded in the research of Barakova et al. (2015). They engaged autism therapy experts with those who could implement human–robotic interaction (HRI) in programming NAO humanoid robots. They also suggested that this utilised the “powers of both: well-defined experimental practices in the domain of autism therapy and state of the art behavioural robotics” (Barakova et al., 2015, p. 699).

These transdisciplinary approaches highlighted the need for what Bevan Jones et al. (2020, p. 929) called expert-led development work “involving all potential users and stakeholders as active collaborators” to embrace the interaction of technology within the psycho-social system. The diversity of the group of parents, service, content, and digital design experts was seen as critical in their work around mental health technologies. This led the research group to advocate for the co-design of digital technologies as it ensures interventions are feasible, engaging, acceptable, and effective.

4. Discussion

In exploring how the co-design process had been implemented with young children in previous health-focused research, it became apparent from the previous literature that a shared definition was needed and that some useful practices could be identified. Thus, based on the review of the literature and examination of additional sources, a clear definition for authentic co-design with children was identified as a transdisciplinary process that involves all stakeholders and potential users as equal collaborators through age-appropriate methods in the development of a product or solution. This draws from the key elements of socio-cultural theory, multiple methodologies, and transdisciplinary perspectives with a specific focus on the co-design of digital tools or solutions—in this instance, with a health literacy focus.

It was also identified that the level of involvement of children in the co-design process varied among the studies, especially with young children, which was identified as a gap in the current research and, therefore, led to the following recommendations for implementation. First, it is proposed that a socio-cultural framework be applied to co-design research with young children. Socio-cultural theory, informed by Vygotskiĭ & Cole’s (1978) work, is commonly used as an explanatory framework for research, learning, and social interaction (Mercer & Howe, 2012). This theory highlights the importance of the relationship between social activity and individual thinking and reinforces the need for time to be given for co-design research. Time is a critical factor in a research environment that often expects researchers to navigate tight time frames that may not consider the need for these relationships to support the inclusion of children’s perspectives throughout the co-design process. This challenges researchers to include flexibility in the planning stage when navigating funding and ethics approval, as clear plans for the technology may be expected at this stage. Time can also be a concern as the pace, cost, and scale of the process required from users and services may not align with funding allocations. Setting a clear timeline for the design process with justification for this often lengthy engagement is recommended (Bevan Jones et al., 2020). Developing innovative solutions to complex education and health-related problems through a socio-cultural lens requires the experiences and culture of an individual to be considered as part of the research process (Sims, 2018). In line with these 11 reviewed studies, health-literacy-focused co-design research should use collaboration between researchers, children, and health practitioners to develop design solutions as a more effective model that benefits all stakeholders.

Second, conducting co-design research through a socio-cultural lens provides benefits to both researchers and participants as the experiences of all individuals are considered. Co-design research is based on the three elements of (a) designers (e.g., the researchers), (b) practitioners (e.g., a teacher, a clinician, children), and (c) the development of an artefact or a framework for improving (Juuti & Lavonen, 2006). Therefore, collaboration between researchers and practitioners in co-design research is essential, with children and teaching/clinical practitioners viewed as co-participants or co-designers (Barab & Squire, 2004; Wang & Hannafin, 2005).

Third, in many instances, children may not be viewed by adults as valuable co-designers throughout the research process. Adult researchers who hold a marginalised view of children may exclude them from parts of the design process due to existing power gaps, biases, and assumptions that young children cannot verbalise their thoughts and feelings (Druin, 2002). Co-designing with children challenges this view, believing that children have rights in the research process and that their views, as end users of a product, are important (Huh et al., 2021; Sims, 2018; Uğur Yavuz et al., 2017). When using co-design with children, researchers should consider how to involve children in co-design in a way that values their opinions and supports their developing autonomy. Thus, children’s voices, as technology end-users, need to be valued throughout the co-design process.

Fourth, children should be viewed as equal stakeholders throughout the co-design process as experts in their own lives. The studies reviewed in this paper alluded to transdisciplinary approaches requiring collaboration across groups of experts (Hoareau et al., 2020), and multiple perspectives were important to ensure the relevance of any health intervention (Cviko et al., 2015). It was identified that the process relied on all collaborators, including children, being seen as “equal stakeholders” (Sims, 2018, p. 23), where a partnership is developed between the potential users and stakeholders to ensure equal contribution from children and adults (Bevan Jones et al., 2020; Sims, 2018). Sims’ (2018) BRIDGE method highlights how children can be given agency in the design process as equal stakeholders through carefully selected methods that recognise children as experts, exploring the views of multiple stakeholders throughout the design process, the production of “high-quality content that is likely to meet users’ needs”, is possible (Hoareau et al., 2020, p. 250). In addition, Lane et al. (2019) highlighted it could be difficult to minimise the power imbalance between adults and children when conducting research. They attempted to use a naturalistic approach by holding discussions with children during play and they argue that aiming to reduce the power imbalance is more feasible than elimination. The diversity of the group should be viewed as a strength in co-design research (Bevan Jones et al., 2020), and it may be useful at times to allocate roles based on experience. For example, the work by Huh et al. (2021) allocated groups based on the expert knowledge of the different users to identify content experts to work in the “subject domain” of content and context, while the “design domain” groups focused on the technology and the usability within the co-design process.

Finally, the use of co-design methods to encourage children’s self-expression, comfort, and creativity can foster children’s input. In line with Sims (2018), using the BRIDGE socio-cultural approach and the use of focus groups and interviews with art materials could be beneficial in future co-design studies. In that vein, the use of dialogic drawing (Ruscoe, 2022), that can be digitally recorded to capture nuanced perspectives from young children could also be highly beneficial in future co-design studies. Dialogic drawing is a participatory multi-model method of data collection where young children engage in dialogue with the researcher using the drawing process to both respond to and as a prompt to research questions (Ruscoe, 2022).

5. Limitations

While the scoping review accessed a range of sources, it is important to note that the scoping review process was not exhaustive, and the use of ‘health literacy’ as a search term also restricted the studies identified to maintain relevance to the larger health literacy design project at hand. This means some relevant studies may not have been accessed through this process. The scoping review was designed to provide an overview of co-design research, specifically for young children and identify gaps in that area, not to be a complete list. However, this does make it a possible limitation for the same reasons. This review process also focused only on refereed journal articles and, as such, did not consider any policy perspectives or other types of ‘grey’ literature that may have assisted in defining these research processes.

6. Conclusions

The discrepancies in what co-design entails, the inconsistencies in the methods used, and the lack of reporting on the co-design processes used in previous research (Halldorsson et al., 2021 clearly highlight a gap in the co-design research in relation to children’s engagement in health literacy tool development. It is evident from the previous literature that there is a need for more co-design with, rather than on, young children when designing any kind of digital technology tools (e.g., apps, VR, interactive games) in the health domain.

This systematic scoping review further supported the claims of others in relation to the scarcity of research utilising co-design with young children to develop tools or to solve problems. This review identified that the use of the word co-design is not consistent, nor is there a clear identification of specific methods to use when enacting the process with young children in previous research. This paper fills a gap in the research by providing a potential definition of co-design with children as well as clearly identifying an effective process when working with young children that is transdisciplinary in nature.

The review has provided insights into how to engage young children in the co-design of a health literacy tool in age-appropriate ways and from the initial stages to ensure the tool is effective for the cohort it is aimed for. By aligning processes to the definition of co-design developed from this review, the next steps of the project can ensure this child-centred engagement with the full development of the tool meets the needs of children under eight. This definition can also be applied to other co-design projects across alternate fields, including education, to ensure children’s rights are upheld and their voices considered in future co-design initiatives.

In terms of meeting the aim of the project, the review identified how co-design has been used with children in the domains of health and technology. However, the inclusion of young children in previous research is limited, and thus, the process should engage children at all stages of the design process to uphold the rights of children as end-users of technology. When wanting to specifically implement this co-design process with young children, child-friendly methodologies should be considered, including drawing, discussions during play, or other age-appropriate methodologies. The children’s voices bring an additional important lens to the transdisciplinary approach which should be considered in the planning of co-design projects, including the allocation of additional time to develop relationships with the children and allow options for them to contribute as equally valued co-constructors.

Funding

This research was funded by the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ARC Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child [CEDC]. (2024). Digital child ethics toolkit: Ethical considerations for digital childhoods research. (Digital Child Working Paper 2024 01). Available online: https://www.digitalchild.org.au/research/publications/working-paper/ethics-toolkit/ (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barab, S., & Squire, K. (2004). Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakova, E. I., Bajracharya, P., Willemsen, M., Lourens, T., & Huskens, B. (2015). Long-term LEGO therapy with humanoid robot for children with ASD. Expert Systems, 32(6), 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan Jones, R., Stallard, P., Agha, S. S., Rice, S., Werner-Seidler, A., Stasiak, K., Kahn, J., Simpson, S. A., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Rice, F., Evans, R., & Merry, S. (2020). Practitioner review: Co-design of digital mental health technologies with children and young people. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 61(8), 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, A., & Straker, L. (2022). How to conduct a transdisciplinary systematic review (with or without meta-analysis) to support decision-making regarding children and digital technology. Digital Child Working Paper 2022-02. ARC Centre of Excellence for the Digital Childhood. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. (2008). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in Healthcare UK. University of York. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?type=supplementary&id=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0201887.s005 (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Cviko, A., McKenney, S., & Voogt, J. (2015). Teachers as co-designers of technology-rich learning activities for early literacy. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 24(4), 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druin, A. (2002). The role of children in the design of new technology. Behaviour & Information Technology, 21(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ey, L. A., & Spears, B. (2020). Engaging early childhood teachers in participatory co-design workshops to educate young children about bullying. Pastoral Care in Education, 38(3), 230–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, W., & Brown, A. (2011). Working with qualitative data (pp. 1–222). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldorsson, B., Hill, C., Waite, P., Partridge, K., Freeman, D., & Creswell, C. (2021). Annual research review: Immersive virtual reality and digital applied gaming interventions for the treatment of mental health problems in children and young people: The need for rigorous treatment development and clinical evaluation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 62(5), 584–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, A. S. (2017). Co-design with children. How to best communicate with and encourage children during a design process. CoDesign, 4(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hoareau, L., Tazouti, Y., Dinet, J., Thomas, A., Luxembourger, C., Hubert, B., Fischer, J. P., & Jarlégan, A. (2020). Co-designing a new educational tablet app for preschoolers. Computers in the Schools, 37(4), 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J., Lee, K. J., Roldan, W., Castro, Y., Kshirsagar, S., Rastogi, P., Kim, I., Miller, K. A., Cockburn, M., & Yip, J. (2021). Making of mobile SunSmart: Co-designing a just-in-time sun protection intervention for children and parents. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 28(6), 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, O. S., Smith, R. C., & Dindler, C. (2017, June 27–30). Child as protagonist: Expanding the role of children in participatory design. 2017 Conference on Interaction Design and Children (pp. 27–37), Stanford, CA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A., & Prout, A. (2015). Prout, Constructing and reconstructing childhood: Contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood (A. James, & A. Prout, Eds.; 3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juuti, K., & Lavonen, J. (2006). Design-based research in science education: One step towards methodology. NorDiNa, 4, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissflow. (2024, April 17). How application development helps in achieving digital transformation. Available online: https://kissflow.com/application-development/digital-application-development/ (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Lane, D., Blank, J., & Jones, P. (2019). Research with children: Context, power, and representation. The Qualitative Report, 24(4), 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. (2018). Conducting educational design research. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, N., & Howe, C. (2012). Explaining the dialogic processes of teaching and learning: The value and potential of sociocultural theory. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 1(1), 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, H. B. R., Ramírez, M. R., & Rojas, E. M. (2018, June 13–16). Digital education using apps for today’s children. 2018 13th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI) (pp. 1–6), Cáceres, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Naismith, L., Lonsdale, P., Vavoula, G. N., & Sharples, M. (2004). Mobile technologies and learning. Report 11. Futurelab. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2019). Student agency for 2030. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/about/projects/edu/education-2040/concept-notes/Student_Agency_for_2030_concept_note.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Peters, M. D., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothong, K., & Livingstone, S. (2023). Children’s rights through children’s eyes: A methodology for consulting children. Digital Futures Commission, 5Rights Foundation. Available online: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/119729/1/Livingstone_childrens_rights_through_childrens_eyes_published.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Ruscoe, A. (2022). Dialogic drawing: A method for researching abstract phenomenon in early childhood. Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 12(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, S., Stones, C., & Macduff, C. (2020). Communicating handwashing to children, as told by children. Health Communication, 35(9), 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, T. (2018). Participatory design of healthcare technology with children. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 31(1), 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure-Jones, T., & Joynes, V. (2018). Co-design of technology-enhanced learning resources. The Clinical Teacher, 15(4), 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğur Yavuz, S. U., Bonetti, R., & Cohen, N. (2017). Designing the “next” smart objects together with children. Design Journal, 20(Suppl. 1), S3789–S3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. Available online: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=child (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Vygotskiĭ, L., & Cole, M. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (p. 159). Harvard University Press. Available online: http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3301299 (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Wang, F., & Hannafin, M. J. (2005). Design-based research and technology: Enhanced learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 53(4), 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L., Visram, S., Hall, A., Sridharan, S., Taylor, A., Sebire, N. J., & Rogers, Y. (2021). Engaging children and young people on medications administration using augmented reality interactive narratives. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 106, A7–A8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieschank, K. L., Machin, T., Day, J., Ireland, M. J., & March, S. (2021). Children’s perspectives on emotions informing a child-reported screening instrument. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(12), 3105–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).