A Pedagogical Translanguaging Proposal for Trainee Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Teaching Proposal

3.1. Setting

3.2. Objective

3.3. Methodology

3.4. Lesson Plan

3.5. Assessment

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECTS | European Credit Transfer System |

| CEFR | Common European Framework of Reference for Languages |

Appendix A

- What are classroom rules?

- Why are classroom rules necessary?

- Which classroom rules did you have when you were at preschool? What are the rules at your university? How has the expected behaviour changed throughout the different stages of education?

| English | Catalan | Spanish | Lx (_________) |

|---|---|---|---|

| We listen to our teacher | |||

| No correm dins de l’edifici | |||

| Recoge los materiales | |||

| We raise our hands before speaking | |||

| Llava’t les mans abans de menjar | |||

| Teacher | English | 1. __________________________________________________ 2. __________________________________________________ 3. __________________________________________________ 4. __________________________________________________ |

| Spanish | 5. __________________________________________________ 6. __________________________________________________ 7. __________________________________________________ 8. __________________________________________________ | |

| Catalan | 9. __________________________________________________ 10. _________________________________________________ 11. _________________________________________________ 12. _________________________________________________ | |

| Lx (______) | 13. _________________________________________________ 14. _________________________________________________ 15. _________________________________________________ 16. _________________________________________________ | |

| Students | English | 17. _________________________________________________ 18. _________________________________________________ 19. _________________________________________________ 20. _________________________________________________ |

| Spanish | 21. _________________________________________________ 22. _________________________________________________ 23. _________________________________________________ 24. _________________________________________________ | |

| Catalan | 25. _________________________________________________ 26. _________________________________________________ 27. _________________________________________________ 28. _________________________________________________ | |

| Lx (______) | 29. _________________________________________________ 30. _________________________________________________ 31. _________________________________________________ 32. _________________________________________________ |

- 1.

- A student is talking while the teacher is speaking.

- 2.

- One student throws a paper to the floor.

- 3.

- A student is talking to his partner and is preventing him from doing his work.

- 4.

- You notice a student who does not look well. He may need to go to the bathroom.

- 5.

- One student has been misbehaving during the class. You want to talk to her in the hallway.

- Have you used similar syntactic structures in the three languages?

- Could you discuss the similarities and differences?

- Did you use the word “please/por favor/per favor” in the three languages? Why or why not?

- Which language or languages do you think are more direct? Why?

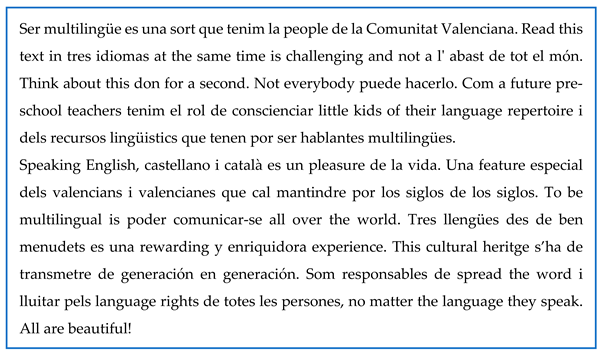

- Do you agree with the text? What are your views on multilingualism?

- What is your own experience with learning languages? What are the main challenges and rewards?

| English | Catalan | Spanish | Lx (_______) |

|---|---|---|---|

- (1)

- A lot of discourse has been generated about multilingualism being a ________ for any country.

- problem

- challenge

- resource

- (2)

- Even if people accept multilingualism, they do not know how to ________ it.

- implement

- study

- discover

- (3)

- Multilingual education begins with the education of ________.

- students

- teachers

- parents

- (4)

- The main problem for teachers in the implementation of multilingual practices is ________.

- attitude

- self-awareness

- both of them

- (5)

- School policies in any country should incorporate ________.

- students’ home languages

- more foreign languages

- just majority languages

References

- Aronin, L. (2021). Dominant language constellations: Teaching and learning languages in a multilingual world. In K. Raza, C. Coombe, & D. Reynolds (Eds.), Policy development in TESOL and multilingualism: Past, present and the way forward (pp. 287–300). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Canagarajah, S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. Modern Language Journal, 95, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco Flores, J., & Jiménez-Cervantes Arnao, M. M. (2018). Competencias y destrezas lingüísticas en la formación del profesorado: Del cómo al qué enseñar. Docencia e Investigación, 28, 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Celic, C., & Seltzer, K. (2013). Translanguaging: A CUNY-NYSIEB guide for educators. Available online: https://www.cuny-nysieb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Translanguaging-Guide-March-2013.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Cenoz, J. (2017). Translanguaging in school contexts: International perspectives. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 16(4), 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2011). Focus on multilingualism: A study of trilingual writing. The Modern Language Journal, 95, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2019). Multilingualism, translanguaging, and minority languages in SLA. The Modern Language Journal, 103, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2020). Teaching English through pedagogical translanguaging. World Englishes and Translanguaging, 39, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2021). Pedagogical translanguaging. Elements in language teaching. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J., & Santos, A. (2020). Implementing pedagogical translanguaging in trilingual schools. System, 92, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Companion Volume. Council of Europe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. (2021). Rethinking the education of multilingual learners. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Angelis. (2021). Multilingual testing and assessment. Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Ebe, A. (2019). Working with Multilingual Learners (MLLs)/English Language Learners (ELLs) resource guide. New York State Education Department. [Google Scholar]

- Franck, J., & Papadopoulou, D. (2024). Pedagogical translanguaging in L2 teaching for adult migrants: Assessing feasibility and emotional impact. Education Sciences, 14(12), 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, A. (2020a). Pedagogical translanguaging in a multilingual English program in Canada: Student and teacher perspectives of challenges. System, 92, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, A. (2020b). Translanguaging for vocabulary improvement: A mixed methods study with international students in a Canadian EAP program. In T. Zhongfeng, L. Aghai, P. Sayer, & J. L. Schissel (Eds.), Envisioning TESOL through a translanguaging lens (pp. 293–328). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Hesson, S. (2015). Translanguaging frameworks for teachers: Macro and micro perspectives. In A. Yiacoumetti (Ed.), Multilingualism and language in education: Current sociolinguistic and pedagogical perspectives from common-wealth countries (pp. 221–242). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., Ibarra-Johnson, S., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The translanguaging classroom: Leveraging student bilingualism for learning. Caslon. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Sylvan, C. E. (2011). Pedagogies and practices in multilingual classrooms: Singularities in pluralities. The Modern Language Journal, 95, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging. Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gorter, D., & Cenoz, J. (2017). Language education policy and multilingual assessment. Language and Education, 31(3), 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, H., & Thoma, D. (2021). Effects of plurilingual teaching on grammatical development in early foreign-language learning. The Modern Language Journal, 105, 464–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonet, O., Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2017). Challenging minority language isolation: Translanguaging in a trilingual school in the Basque Country. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 16(4), 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonet, O., Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2020). Developing morphological awareness across languages: Translanguaging pedagogies in third language acquisition. Language Awareness, 29(1), 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonet, O., & Saragueta, E. (2023). The case of a pedagogical translanguaging intervention in a trilingual primary school: The students’ voice. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanes, À., & Cots, J. M. (2022). Measuring the impact of translanguaging in TESOL: A plurilingual approach to ESP. International Journal of Multilingualism, 19(4), 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llurda, E. (2020). Aprendre anglès per a parlar amb el món: Reflexions al voltant de l’ensenyament de l’anglès com a llengua franca global. Caplletra, 68, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyster, R., Quiroga, J., & Ballinger, S. (2013). The effects of biliteracy instruction on morphological awareness. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 1(2), 169–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, O., & Guzmán-Alcón, I. (2024). Learner pragmatics in English-medium-instruction courses at university: Current research and future avenues. Applied Pragmatics, 6(2), 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, S. (2013). The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and bilingual education. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orcasitas-Vicandi, M., & Perales-Fernández-de-Gamboa, A. (2024). Promoting pedagogical translanguaging in pre-service teachers’ training: Material design for a multilingual context with a regional minority language. International Journal of Multilingualism, 21(1), 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsrud, B., & Gheitasi, P. (2024). Embracing linguistic diversity: Pre-Service teachers’ lesson planning for English language learning in Sweden. Education Sciences, 14(12), 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portolés, L., & Basgall, L. (2024). Translanguaging and the Role of the L1 in CLIL Classrooms: Beliefs of In-Service Teachers. In D. Gabryś-Barker, & E. Vetter (Eds.), Modern approaches to researching multilingualism. Second language learning and teaching (pp. 183–204). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portolés, L., & Gayete, G. (2024). Enhancing multilingual young students’ pragmatic awareness through pedagogical translanguaging. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, K. (2024). Translanguaging in Multilingual Education. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp. 1–8). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usó-Juan, E., & Martínez-Flor, A. (2006). Approaches to language learning and teaching: Towards acquiring communicative competence through the four skills. In E. Usó-Juan, & A. Martínez-Flor (Eds.), Current trends in the development and teaching of the four language skills (pp. 3–26). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Vetter, E., & Slavkok, N. (2022). How to learn to teach multilingual learning. AILA Review, 35(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. (1994). Arfarniad o ddulliau dysgu ac addysgu yng nghyddestun addysg uwchradd ddwyieithog (an evaluation of teaching and learning methods in the context of bilingual secondary education) [Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Wales]. [Google Scholar]

- Wlosowicz, T. M. (2020). The use of elements of translanguaging in teaching third or additional languages: Some advantages and limitations. Multidisciplinary Journal of School Education, 9(17), 135–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar Yuzlu, M., & Dikilitas, K. (2021). Translanguaging in the development of EFL learners’ foreign language skills in Turkish context. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 16(2), 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TEACHING UNIT: CLASSROOM RULES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task | Duration | Competences and Language Skills | Translanguaging Practice | Objectives |

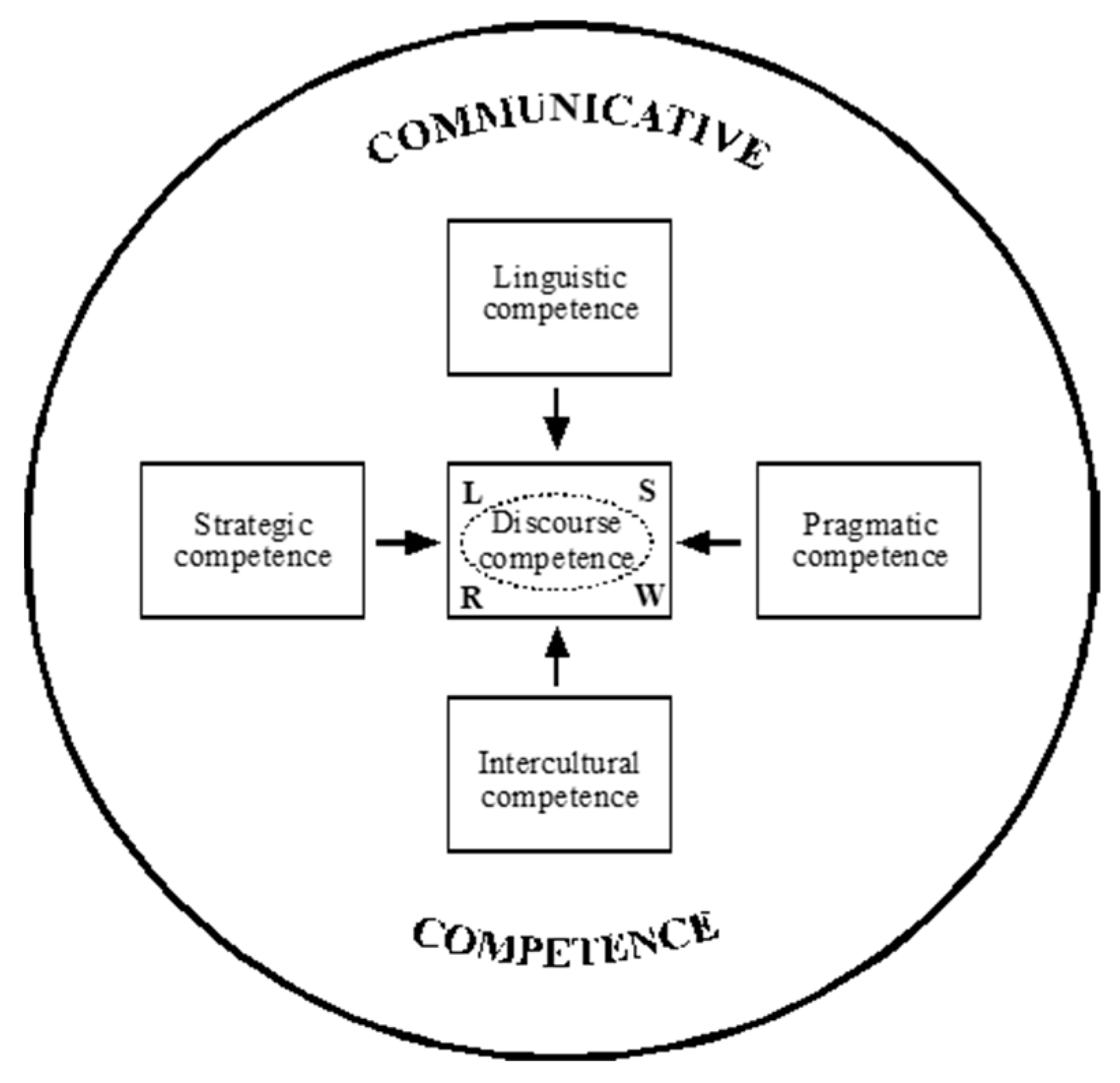

| Task 1 | 10 min | Discourse Linguistic Intercultural Strategic Writing Speaking | Use of whole language repertoire Students brainstorm in any language and write in English | * Reflect on the importance of classroom rules in the preschool setting * Discuss how classroom rules evolve throughout the different educational stages * Think critically about the evolution of rules and the roles of students and teachers. * Define and discuss issues related to teacher education. |

| Task 2 | 15 min | Discourse Linguistic Pragmatic Intercultural Writing | Enhancing metalinguistic awareness Students write simultaneously in their L1, L2, and L3 to build linguistic connections across their linguistic repertoire | * Analyse the grammar structures used to express classroom rules in English, Catalan, and Spanish. Other languages may be included. * Introduce the imperative form and other grammatical structures in the three languages. * Compare the forms in the languages used and find similarities and differences. * Research classroom rules in other cultures and compare them to the rules in their country. |

| Task 3 | 15 min | Strategic Pragmatic Intercultural Listening | Translanguaging shifts The task is in English, but the students and the teacher may use other languages for any communicative need in the classroom | * Identify classroom rules and behaviour. * Introduce pragmatic concepts, such as requests, strategies, and modifiers used to make requests. * Examine how teachers and students ask for things. * Discuss the degrees of politeness in educational settings. * Focus on sociopragmatic aspects, such as social distance, relative power, and degree of imposition. |

| Task 4 | Home | Pragmatic Strategic Linguistic Discourse Intercultural Speaking | Use of whole language repertoire Students create a multilingual digitally recorded video | * Promote students’ creativity by making a multilingual video in which they teach the class rules themselves. * Integrate technology into the language classroom. * Improve oral competence * Evaluate the work of peers, providing positive aspects and suggestions for improvement. |

| Task 5 | 10 min | Pragmatic Linguistic Intercultural Writing | Enhancing metalinguistic awareness Students compare their L1, L2 and L3 to develop pragmatic awareness and produce requests in each language | * Develop pragmatic awareness in the three languages of instruction by making them think about how they will ask for materials, permission, etc., in the three languages. * Understand basic request types and modifiers * Discuss how cultural norms may influence the politeness style |

| Task 6 | 15 min | Pragmatic Linguistic Intercultural Strategic Writing Speaking | Use of whole language repertoire Students engage in a multilingual brainstorm, leveraging cross-linguistic transfer of knowledge and skills to complete the task | * Familiarise students with the common classroom discourse used in preschool settings * Explore effective communication strategies employed by teachers * Promote students’ critical thinking and problem-solving. |

| Task 7 | 5 min | Pragmatic Strategic Linguistic Discourse Intercultural Writing Speaking | Enhancing metalinguistic awareness Students reflect on and compare the syntactic and pragmatic features of their whole language repertoire | * Compare the sentence structure, pronoun use, and verbs in Catalan, Spanish, and English. * Discuss which language seems more direct. * Develop sensitivity to linguistic backgrounds. * Search for real-life examples in the three languages. |

| Task 8 | 20 min | Linguistic Discourse Intercultural Reading Speaking | Use of whole language repertoire Students read a multilingual text and reflect on their multilingual language experience and identity | * Value their multilingual identity * Reflect on their language learning experiences * Discuss multilingualism and its benefits * Develop positive attitudes towards languages * Introduce the concept of Dominant Language Constellation * Foster sensitivity to language diversity in the multilingual classroom |

| Task 9 | 10 min | Linguistic Intercultural Reading | Enhancing metalinguistic awareness Students activate prior knowledge in their L1 and L2 vocabulary to facilitate L3 production using cognate charts | * To introduce the term cognate and make them reflect on its meaning and how it can be used for language learning. * Compare the lexical similarities and differences in the three languages. * Improve reading comprehension skills * Expand vocabulary in three languages * Integrate ICT tools in language learning |

| Task 10 | 5 min | Linguistic Intercultural Speaking | Use of whole language repertoire Students do online research and explore idiomatic expressions in the three languages. | * Explore idiomatic expressions in the three languages * Analyse and compare the similarities and differences of the three languages. * Use of online tools |

| Task 11 | 15 min | Discourse Intercultural Listening Speaking | Translanguaging shifts The task is in English, but the students and the teacher may use other languages for any communicative need in the classroom | * Understand messages related to educational issues * Express ideas and opinions about multilingualism * Reflect on ways of learning and teaching languages |

| Task 12 | Home | Pragmatic Strategic Linguistic Discourse Intercultural Writing | Translanguaging shifts Essays will be written in English. Reviewers will provide feedback in English, although other languages can be used for clarification | * Write an opinion essay describing experiences and views on topics which are related to education * Peer-review students’ drafts to facilitate constructive feedback * Evaluate the revised essays for improvements * Reflect upon using a multilingual approach in the classroom |

| Building on Pluricultural Repertoire | Can generally act according to conventions regarding posture, eye contact, and distance from others. |

| Can generally respond appropriately to the most commonly used cultural cues. | |

| Can explain features of their own culture to members of another culture or explain features of the other culture to members of their own culture. | |

| Can explain in simple terms how their own values and behaviors influence their views of other people’s values and behaviors. | |

| Can discuss in simple terms the way in which things that may look “strange” to them in another sociocultural context may well be “normal” for the other people concerned. | |

| Can discuss in simple terms the way their own culturally determined actions may be perceived differently by people from other cultures. | |

| Plurilingual Comprehension | Can use what they have understood in one language to understand the topic and main message of a text in another language (e.g., when reading short newspaper articles in different languages on the same theme). Can use parallel translations of texts (e.g., magazine articles, stories, passages from novels) to develop comprehension in different languages. |

| Can deduce the message of a text by exploiting what they have understood from texts on the same theme in different languages (e.g., news in brief, museum brochures, online reviews). | |

| Can extract information from documents in different languages in their field (e.g., to include in a presentation). | |

| Can recognize similarities and contrasts between the way concepts are expressed in different languages, in order to distinguish between identical uses of the same word/sign and “false friends”. | |

| Can use their knowledge of contrasting grammatical structures and functional expressions of languages in their plurilingual repertoire in order to support comprehension. | |

| Building on Plurilingual Repertoire | Can exploit creatively their limited repertoire in different languages in their plurilingual repertoire for everyday contexts, in order to cope with an unexpected situation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Portolés, L. A Pedagogical Translanguaging Proposal for Trainee Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 648. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060648

Portolés L. A Pedagogical Translanguaging Proposal for Trainee Teachers. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):648. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060648

Chicago/Turabian StylePortolés, Laura. 2025. "A Pedagogical Translanguaging Proposal for Trainee Teachers" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 648. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060648

APA StylePortolés, L. (2025). A Pedagogical Translanguaging Proposal for Trainee Teachers. Education Sciences, 15(6), 648. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060648