The Impact of the Soundscape on University Life: Critical Music Education as a Tool for Awareness and Transformation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What is the emotional impact of the soundscape on preservice teachers enrolled in music education courses?

- RQ2: How do preservice teachers perceive their campus soundscapes, and how do these affect their university experience?

- RQ3: What pedagogical strategies can be implemented to address noise pollution in the music classroom?

1.1. The Impact of Noise on University Life

1.2. Critical Music Education and Reflection on the Soundscape

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Context

2.2. Data Collection Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

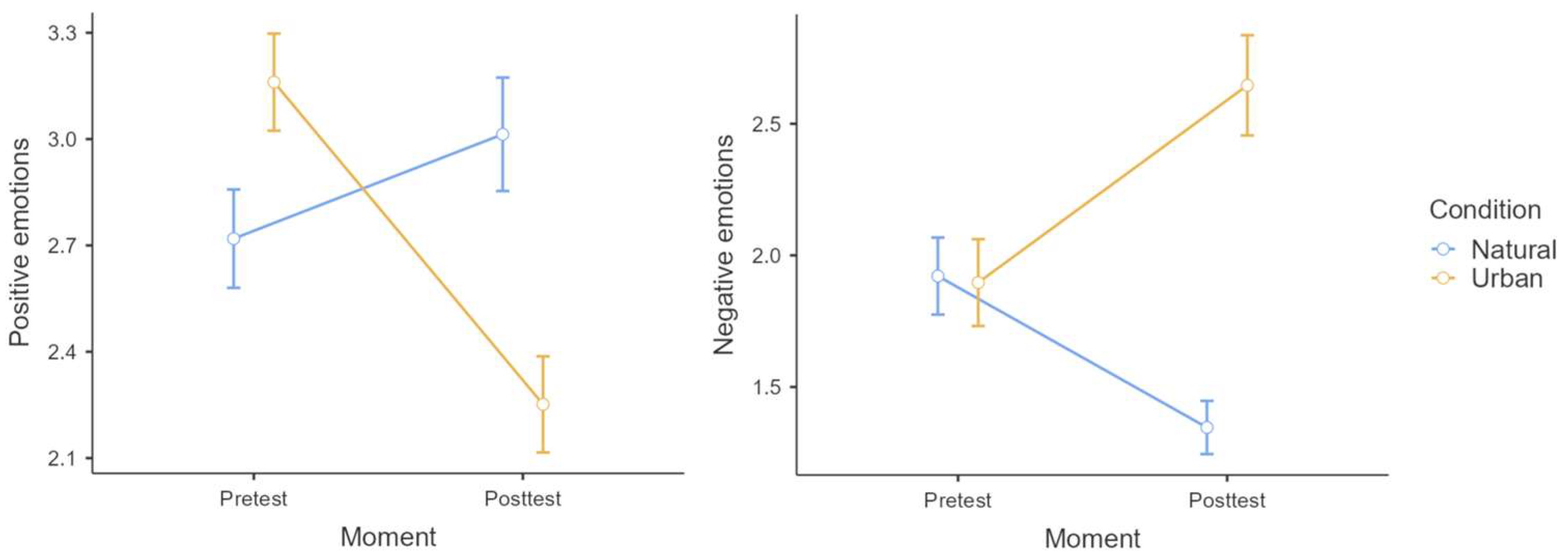

3.1. Quasi-Experimental Design

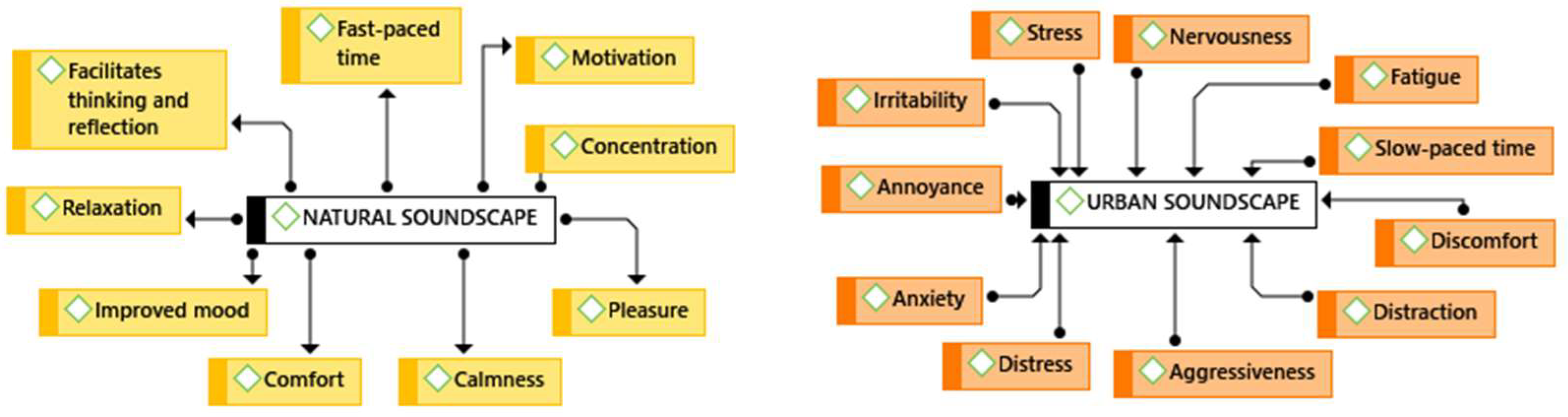

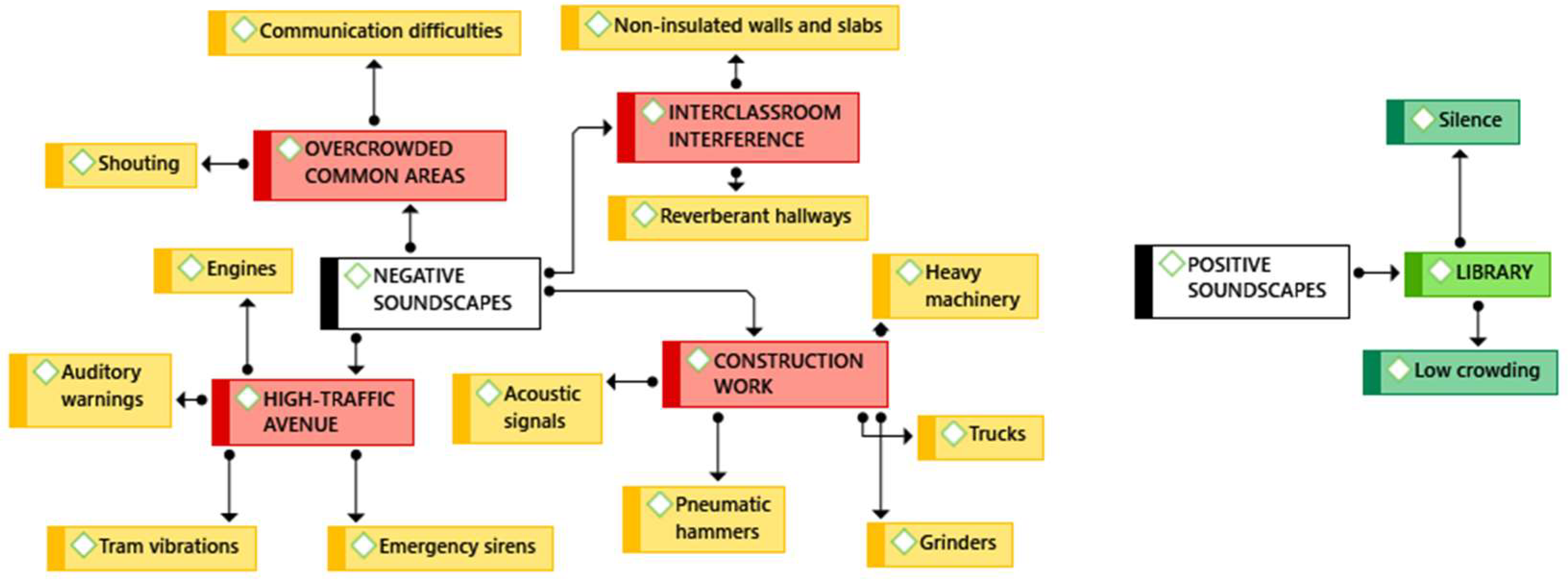

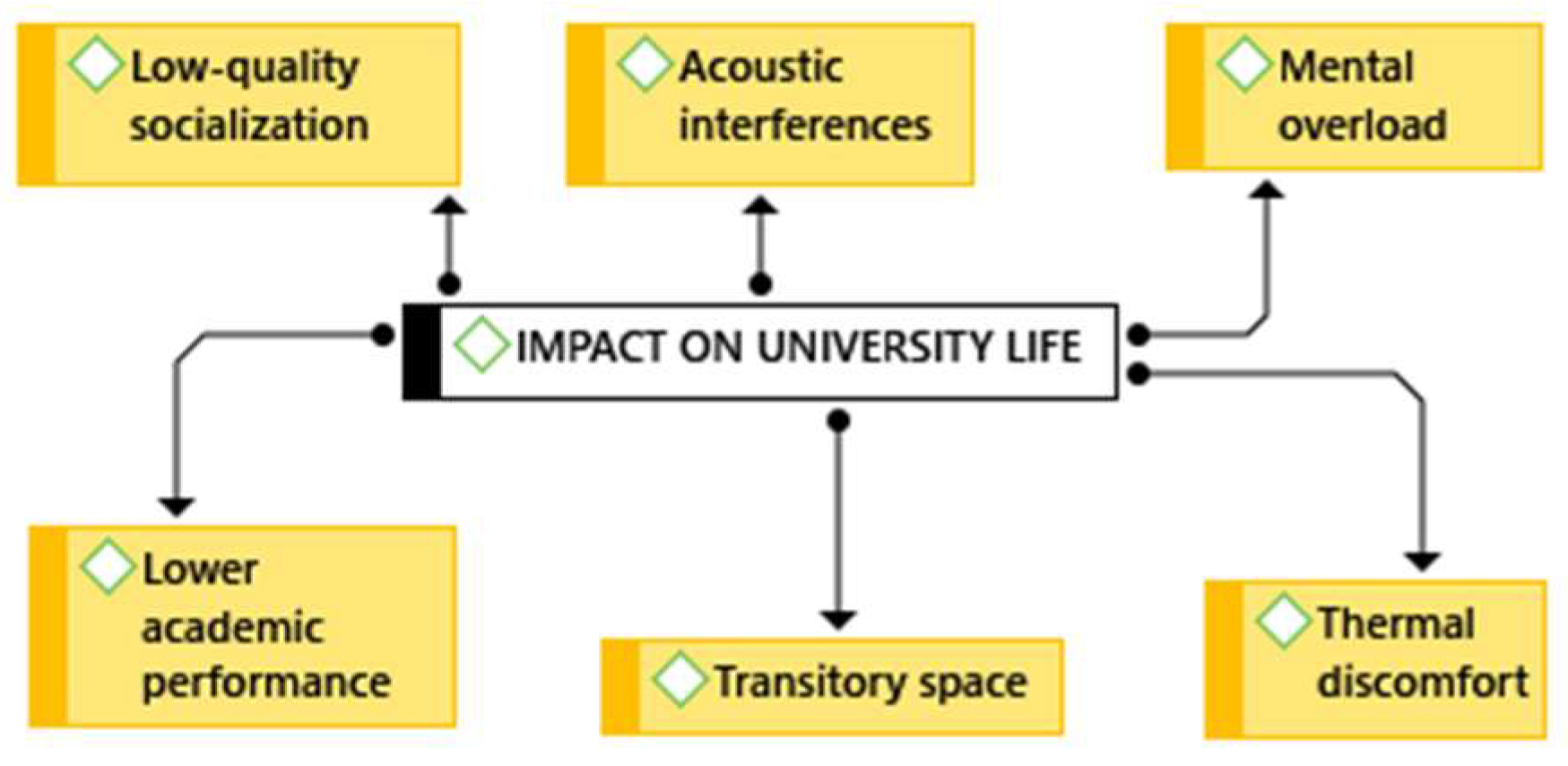

3.2. Focus Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akbari, E. (2016). Soundscape compositions for art classrooms. Art Education, 69(4), 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z., & Zhang, S. (2024). Effects of different natural soundscapes on human psychophysiology in national forest park. Scientific Reports, 14, 17462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A. M., Sonn, C. C., & Meyer, K. (2020). Voices of displacement: A methodology of sound portraits exploring identity and belonging. Qualitative Research, 20(6), 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P., Davies, F., Zhang, Y., & Barrett, L. (2017). The holistic impact of classroom spaces on learning in specific subjects. Environment and Behavior, 49(4), 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellet, C. (2011). La inserción de la universidad en la estructura y forma urbana. el caso de la Universitat de Lleida. Scripta Nova. Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales, 14(381), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Beringer, A., & Adomßent, M. (2008). Sustainable university research and development: Inspecting sustainability in higher education research. Environmental Education Research, 14(6), 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanca, M. J., Alarcón, R., Arnau, J., Bono, R., & Bendayam, R. (2017). Non-normal data: Is ANOVA stil a valid option? Psicothema, 29(4), 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, A. M. (2020). El paisaje sonoro como arte sonoro. Cuadernos de Música, Artes Visuales y Artes Escénicas, 15(1), 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, A. M., & Ramos, P. (2024). Paisajes sonoros en extinción: Una situación de aprendizaje de música para educación secundaria. Per Musi, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D. (2012). Avoiding the “P” word: Political contexts and multicultural music education. Theory into practice, 51(3), 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, R. T., Pearson, A. L., Allou, C., Fristrup, K., & Wittemyer, G. (2021). A synthesis of health benefits of natural sounds and their distribution in national parks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(14), e2013097118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carles, J. L. (2007, June 12–15). El paisaje sonoro, una herramienta interdisciplinar: Análisis, creación y pedagogía con el sonido. Encuentros Iberoamericanos Sobre Paisajes Sonoros, Madrid, Spain. Available online: https://cvc.cervantes.es/artes/paisajes_sonoros/p_sonoros01/carles/carles_01.htm (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Cárdenas-Soler, R. N., & Martínez-Chaparro, D. (2015). El paisaje sonoro, una aproximación teórica desde la semiótica. Revista de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación, 5(2), 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, M. (2016). Music education and/in rural social space: Making space for musical diversity beyond the city. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 15(4), 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L. (2017). Campus de excelencia internacional. Hacia una reforma estructural del Sistema Universitario Español. La Cuestión Universitaria, 1(9), 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría, R., de Lille, M. J., Evia, N., & Carrillo, C. (2021). Convivencia universitaria inclusiva, democrática y pacífica: De lo personal a lo institucional. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 20(43), 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. I. (2023). Soundcurrents: Exploring sound’s potential to catalyze creative critical consciousness in adolescent music students and undergraduate music education majors [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Western Ontario]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2800162936/fulltextPDF/AA58A14189324B0EPQ/1?accountid=14777&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Escamilla, J. O. G. (2024). Desafíos y oportunidades para el futuro desarrollo sostenible de las ciudades. Cuadernos de Arquitectura y Asuntos Urbanos, Revista de la Facultad de Arquitectura, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, 14(14), 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fiebig, A., Jordan, P., & Moshona, C. C. (2020). Assessments of acoustic environments by emotions—The application of emotion theory in soundscape. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 573041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fincham, F. D., & Linfield, K. J. (1997). A new look quality: Can spouses feel positive and negative about their marriage? Journal of Family Psychology, 11(4), 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalitat Valenciana. (2002). LEY 7/2002, de 3 de diciembre, de la Generalitat Valenciana, de protección contra la contaminación acústica. [2002/13497] (Vol. 4394, pp. 31214–31233). DOGV. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es-vc/l/2002/12/03/7 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- German-González, M., & Santillán, A. O. (2006). Del concepto de ruido urbano al de paisaje sonoro. Revista Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 10(1), 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour, L. R. V., Bray, I., Alford, C., & Lintott, P. R. (2024). Natural soundscapes enhance mood recovery amid anthropogenic noise pollution. PLoS ONE, 19(11), e0311487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Zamar, M. D., & Abad-Segura, E. (2020). Diseño del espacio educativo universitario y su impacto en el proceso académico: Análisis de tendencias. Revista de Estilos de Aprendizaje, 13(25), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, S., & Scott, W. (2007). Higher education and sustainable development: Paradox and possibilities. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, J. L. (2020). ART Relaciones interpersonales y situaciones de convivencia en el aula universitaria. Revista Arjé, 3(1), 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, S. X. G. (2018). El paisaje sonoro como herramienta de sensibilización en el aula ante la contaminación acústica en las ciudades. Revista Internacional de Aprendizaje en la Educación Superior, 5(2), 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahad, O., Kuntic, M., Al-Kindi, S., Kuntic, I., Gilan, D., Petrowski, K., Daiber, A., & Münzel, T. (2025). Noise and mental health: Evidence, mechanisms, and consequences. Journal of Exposure Science Environment Epidemiology, 35, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurtado, A., & Botella, A. M. (2023). El paisaje sonoro y visual como recurso educativo para la formación del profesorado. Human Review, 17(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, A., Botella, A. M., Fernández, R., & Martínez, S. (2023). Development of social and environmental competences of teachers in training using sound and visual landscape. Education Sciences, 13(6), 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, A., Botella, A. M., & Martínez, S. (2022). Virtual and augmented reality applied to the perception of the sound and visual garden. Education Sciences, 12(6), 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S. A. (2023). Reviewing the effects of noise pollution on students (college and university). AIP Conference Proceedings, 2591(1), 030056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, C. C. (2014). Noise exposure in the Malaysian living environment from a music education perspective. Malaysian Journal of Music, 3(2), 32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Klatte, M., Spilski, J., Mayerl, J., Möhler, U., Lachmann, T., & Bergström, K. (2017). Effects of aircraft noise on reading and quality of life in primary school children in germany: Results from the NORAH study. Environment and Behavior, 49(4), 390–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A., Martino, E., Mansour, A., & Bentley, R. (2022). Environmental noise exposure and mental health: Evidence from a population-based longitudinal study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 63(2), 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Q., Lin, S., Wang, L., Yang, F., & Yang, Y. (2024). The impact of campus soundscape on enhancing student emotional well-being: A case study of fuzhou university. Buildings, 15(1), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J., Kweon, K., Kim, H. W., Cho, S. W., Park, J., & Sim, C. S. (2018). Negative impact of noise and noise sensitivity on mental health in childhood. Noise & Health, 20(96), 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Lopera, C. A., Lopera, M. P., & Duque, D. A. (2019). La universidad verde: Percepciones de la comunidad universitaria en el proceso de transformación hacia la sostenibilidad. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte, 1(57), 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Liébana, P., Blasco Magraner, J. S., & Botella Nicolás, A. M. (2021). Hacia una conceptualización de la educación musical crítica: Aplicación de los paradigmas científicos, las teorías curriculares y los modelos didácticos. Márgenes, Revista de Educación de la Universidad de Málaga, 2(2), 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, M. L., Puertas, R. M., & Calafat, M. C. (2019, November 6–8). La sostenibilidad en las universidades públicas valencianas: Una comparativa cronológica y con otros campus españoles. INNODOCT 2019 (pp. 461–469), Valencia, Spain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Usarralde, M. J., Lloret-Catalá, C., & Mas-Gil, S. (2017). Responsabilidad Social Universitaria (RSU): Principios para una universidad sostenible, cooperativa y democrática desde el diagnóstico participativo de su alumnado. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 25, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, O., Shepherd, D., & Hautus, M. J. (2015). The restorative potential of soundscapes: A physiological investigation. Applied Acoustics, 96, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, A. P. (2017). Conocer el entorno social de la Música, una condición necesaria en la Educación Musical Postmoderna. Dedica Revista de Educação e Humanidades, 12, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, S., Zengin, M., & Yilmat, H. (2014). Determination of the noise pollution on university (education) campuses: A case study of ataturk university. Ekoloji, 23(90), 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, M., Skenteris, N., & Piperakis, S. (2015). Effect of external classroom noise on schoolchildren’s reading and mathematics performance: Correlation of noise levels and gender. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 27(1), 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauta, P. (2019). La función sonora en el diálogo intercultural. In J. G. Rendón (Ed.), Interculturalidad y artes: Derivas del arte para el proyecto intercultural (pp. 163–194). UArtes Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Paynter, J., & Aston, P. (1970). Sound and silence: Classroom projects in creative music. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pijanowski, B. C., Villanueva-Rivera, L. J., Dumyahn, S. L., Farina, A., Krause, B., Napoletano, B. M., Gage, S. H., & Pieretti, N. (2011). Soundscape ecology: The science of sound in the landscape. BioScience, 61(3), 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, L. (2015). Comunidad acústica e identidad sónica. Una perspectiva crítica sobre el paisaje sonoro contemporáneo. Panambí. Revista De Investigaciones Artísticas, 1, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, K. M., Hossieni, H., Ahmad, S. S., Ali, H., & Kawa, H. (2015). Study of the improvement of noise pollution in university of sulaimani in both new and old campus. Journal of Pollution Effects & Control, 3(3), 1000143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G. (2017). Multiculturalidad, interdisciplinariedad y paisaje sonoro (soundscape) en la educación musical universitaria de los futuros maestros en educación infantil. Dedica. Revista de Educação e Humanidades, 11, 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Sandín, B., Chorot, P., Lostao, L., Joiner, T. E., Santed, M. A., & Valiente, R. M. (1999). Escalas PANAS de afecto positivo y negativo: Validación factorial y convergencia transcultural. Psicothema, 11(1), 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, R. M. (1975). The rhinoceros in the classroom. Universal Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, R. M. (1976). Creative music education: A handbook for the modern music teacher. Schirmer Books. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, R. M. (1977). The tuning of the world. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Shayegh, J., Drury, J., & Stevenson, C. (2017). Listen to the band! How sound can realize group identity and enact intergroup domination. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56(1), 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B., Zhang, H., Du, J., Na, N., Xu, Y., & Kang, J. (2024). The influence of general music education on the perception of soundscape. International Journal of Acoustics and Vibrations, 29(1), 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speake, J., Edmonson, S., & Nawaz, H. (2013). Everyday encounters with nature: Students’ perceptions and use of university campus green spaces. Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography, 7(1), 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L. M., Weinberg, J., & Keaney, J. F. (2016). Common statistical pitfalls in basic science research. Journal of the American Heart Association, 5(10), e004142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, J., Murillo, A., & Berenguer, J. M. (2023). Acouscapes: A software for ecoacoustic education and soundscape composition in primary and secondary education. Organised Sound, 29(1), 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R., Smith, R., Karim, Y. B., Shen, C., Drummond, K., Teng, C., & Toledano, M. B. (2022). Noise pollution and human cognition: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of recent evidence. Environment International, 158, 106905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truax, B. (1984). Acoustic communication. Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, E. M. (2015). Mapa acústico del campus universitario (edificios académicos). Universidad Tecnológica de El Salvador. Vicerrectoria de Investigacion. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11298/202 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D., Hubbard, B., & Wiese, D. (2000). General traits of personality and affectivity as predictors of satisfaction in intimate relationships: Evidence from self-and partner-ratings. Journal of Personality, 68(3), 413–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, H. (2006). Democracy and music education: Liberalism, ethics, and the politics of practice. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 14(2), 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2018). Environmental noise guidelines for the European Region (pp. 1–160). World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/279952/9789289053563-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 72 | 80.85% |

| Male | 17 | 19.15% | |

| Age | 18–19 years | 54 | 60.67% |

| 20–21 years | 28 | 31.46% | |

| >21 years | 7 | 7.87% | |

| Specialized musical training | Yes | 30 | 26.70% |

| No | 59 | 66.29% | |

| Group | Music education | 30 | 33.71% |

| General education | 59 | 66.29% |

| Moment | Condition | Mom*Cond | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(1,88) | p | np2 | F(1,88) | p | np2 | F(1,88) | p | np2 | |

| Positives | 43.11 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 4.90 | 0.029 | 0.05 | 109.76 | <0.001 | 0.55 |

| Active | 31.61 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 5.94 | 0.017 | 0.06 | 13.01 | <0.001 | 0.13 |

| Attentive | 13.92 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 8.53 | 0.004 | 0.09 | 104.56 | <0.001 | 0.54 |

| Determined | 11.34 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.62 | 0.013 | 0.07 | 54.53 | <0.001 | 0.38 |

| Alert | 28.68 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 14.02 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 10.35 | 0.002 | 0.11 |

| Enthusiastic | 15.08 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 13.24 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 112.57 | <0.001 | 0.56 |

| Strong | 21.13 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 2.30 | 0.133 | 0.03 | 36.88 | <0.001 | 0.30 |

| Excited | 13.55 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 13.21 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 54.55 | <0.001 | 0.38 |

| Inspired | 6.44 | 0.013 | 0.07 | 7.98 | 0.006 | 0.08 | 64.48 | <0.001 | 0.42 |

| Interested | 24.11 | <0.001 | 0.21 | 15.27 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 60.62 | <0.001 | 0.41 |

| Proud | 3.10 | 0.082 | 0.03 | 8.40 | 0.005 | 0.09 | 48.73 | <0.001 | 0.36 |

| Negatives | 1.95 | 0.166 | 0.02 | 87.77 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 128.59 | <0.001 | 0.59 |

| Upset | 1.19 | 0.278 | 0.01 | 83.32 | <0.001 | 0.49 | 62.64 | <0.001 | 0.42 |

| Jittery | 1.53 | 0.219 | 0.02 | 36.83 | <0.001 | 0.30 | 59.46 | <0.001 | 0.40 |

| Hostile | 0.56 | 0.454 | 0.01 | 8.60 | 0.004 | 0.09 | 18.36 | <0.001 | 0.17 |

| Distressed | 2.05 | 0.091 | 0.03 | 30.78 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 37.81 | <0.001 | 0.30 |

| Scared | 10.38 | 0.002 | 0.11 | 44.85 | <0.001 | 0.34 | 51.61 | <0.001 | 0.37 |

| Ashamed | 1.87 | 0.174 | 0.02 | 45.39 | <0.001 | 0.34 | 138.99 | <0.001 | 0.61 |

| Guilty | 1.63 | 0.205 | 0.02 | 4.86 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 10.14 | 0.002 | 0.10 |

| Irritable | 0.29 | 0.594 | 0.00 | 68.36 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 63.04 | <0.001 | 0.42 |

| Afraid | 2.95 | 0.089 | 0.03 | 69.70 | <0.001 | 0.44 | 100.25 | <0.001 | 0.53 |

| Nervous | 0.2 | 0.887 | 0 | 21.67 | <0.001 | 0.2 | 38.31 | <0.001 | 0.30 |

| Pretest-Posttest Natural | Pretest-Posttest Urban | Posttest Natural-Posttest Urban | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t(1,88) | p | d | t(1,88) | p | d | t(1,88) | p | d | |

| Positives | −3.84 | <0.001 | 0.72 | 12.71 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 7.91 | <0.001 | 0.91 |

| Active | 0.69 | 0.245 | 1.37 | 7.12 | <0.001 | 1.12 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 1.45 |

| Attentive | −4.89 | <0.001 | 1.24 | 10.55 | <0.001 | 1.14 | 8.81 | <0.001 | 1.32 |

| Determined | −2.74 | 0.004 | 1.08 | 7.48 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 6.60 | <0.001 | 1.19 |

| Alert | 0.88 | 0.192 | 1.21 | 5.88 | <0.001 | 1.21 | −1.05 | 0.297 | 1.52 |

| Enthusiastic | −4.02 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 9.88 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 9.25 | <0.001 | 1.10 |

| Strong | −1.81 | 0.037 | 1.06 | 7.82 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 5.55 | <0.001 | 1.13 |

| Excited | −3.16 | 0.001 | 0.84 | 6.95 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 7.03 | <0.001 | 1.19 |

| Inspired | −4.58 | <0.001 | 1.16 | 7.42 | <0.001 | 1.26 | 7.49 | <0.001 | 1.36 |

| Interested | −2.51 | 0.007 | 1.06 | 9.23 | <0.001 | 1.02 | 7.46 | <0.001 | 1.32 |

| Proud | −4.50 | <0.001 | 0.97 | 6.50 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 5.92 | <0.001 | 1.40 |

| Negatives | 10.99 | <0.001 | 0.49 | −6.88 | <0.001 | 1.03 | −13.03 | <0.001 | 0.94 |

| Upset | 6.67 | <0.001 | 0.81 | −5.62 | <0.001 | 1.26 | −9.46 | <0.001 | 1.38 |

| Jittery | 7.96 | <0.001 | 0.97 | −6.78 | <0.001 | 1.63 | −12.55 | <0.001 | 1.45 |

| Hostile | 4.45 | <0.001 | 0.83 | −6.00 | <0.001 | 1.52 | −8.89 | <0.001 | 1.40 |

| Distressed | 5.76 | <0.001 | 1.16 | −5.62 | <0.001 | 1.57 | −11.59 | <0.001 | 1.48 |

| Scared | 4.06 | <0.001 | 0.78 | −4.37 | <0.001 | 1.38 | −7.54 | <0.001 | 1.27 |

| Ashamed | 3.82 | <0.001 | 0.78 | −1.18 | 0.121 | 1.08 | −3.64 | <0.001 | 1.11 |

| Guilty | 4.86 | <0.001 | 0.68 | −1.91 | 0.03 | 1.17 | −5.05 | <0.001 | 1.13 |

| Irritable | 8.89 | <0.001 | 1.05 | −7.93 | <0.001 | 1.50 | −12.33 | <0.001 | 1.42 |

| Afraid | 5.78 | <0.001 | 0.77 | −3.69 | <0.001 | 1.26 | −6.83 | <0.001 | 1.72 |

| Nervous | 6.78 | <0.001 | 1.11 | −5.14 | <0.001 | 1.67 | −10.20 | <0.001 | 1.60 |

| Pretest (Nat.) | Pretest (Urb.) | Posttest (Nat.) | Posttest (Urb.) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Positives | 2.71 | 0.66 | 3.16 | 0.65 | 3.01 | 0.75 | 2.25 | 0.64 |

| Active | 2.62 | 1.09 | 3.27 | 0.94 | 2.52 | 1.00 | 2.43 | 1.03 |

| Attentive | 2.44 | 0.90 | 3.11 | 0.96 | 3.08 | 1.03 | 1.84 | 0.88 |

| Determined | 2.78 | 0.91 | 3.13 | 0.93 | 3.09 | 1.00 | 2.26 | 0.91 |

| Alert | 2.51 | 1.15 | 3.31 | 1.11 | 2.39 | 1.03 | 2.56 | 1.13 |

| Enthusiastic | 2.66 | 0.90 | 3.02 | 1.03 | 3.08 | 0.96 | 2.00 | 0.83 |

| Strong | 2.70 | 1.04 | 3.07 | 1.02 | 2.90 | 1.10 | 2.24 | 0.85 |

| Excited | 2.79 | 0.94 | 3.00 | 0.97 | 3.07 | 0.96 | 2.18 | 0.83 |

| Inspired | 2.42 | 1.00 | 2.89 | 1.01 | 2.98 | 1.01 | 1.90 | 0.88 |

| Interested | 3.09 | 0.83 | 3.33 | 0.89 | 3.37 | 0.88 | 2.33 | 0.95 |

| Proud | 3.20 | 0.91 | 3.47 | 1.04 | 3.66 | 1.09 | 2.79 | 1.15 |

| Negatives | 1.92 | 0.69 | 1.90 | 0.78 | 1.35 | 0.48 | 2.65 | 0.91 |

| Upset | 2.08 | 1.01 | 2.13 | 1.11 | 1.51 | 0.81 | 2.89 | 1.19 |

| Jittery | 2.13 | 1.13 | 2.08 | 1.18 | 1.31 | 0.65 | 3.25 | 1.30 |

| Hostile | 1.58 | 0.94 | 1.54 | 1.00 | 1.19 | 0.54 | 2.51 | 1.30 |

| Distressed | 2.25 | 1.24 | 2.43 | 1.15 | 1.54 | 0.91 | 3.36 | 1.26 |

| Scared | 1.58 | 0.98 | 1.62 | 0.94 | 1.25 | 0.61 | 2.26 | 1.29 |

| Ashamed | 1.58 | 0.89 | 1.56 | 0.95 | 1.27 | 0.69 | 1.70 | 0.96 |

| Guilty | 1.62 | 0.94 | 1.64 | 1.06 | 1.27 | 0.67 | 1.88 | 1.12 |

| Irritable | 2.45 | 1.16 | 2.06 | 1.07 | 1.46 | 0.85 | 3.31 | 1.28 |

| Afraid | 1.64 | 0.91 | 1.60 | 0.93 | 1.17 | 0.57 | 2.09 | 1.26 |

| Nervous | 2.29 | 1.25 | 2.31 | 1.29 | 1.49 | 0.83 | 3.22 | 1.36 |

| Moment*Gender | Condition*Gender | Mom*Cond*Gend | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(1,88) | p | np2 | F(1,88) | p | np2 | F(1,88) | p | np2 | |

| Positives | 4.55 | 0.036 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.603 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.629 | 0.00 |

| Negatives | 0.73 | 0.395 | 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.838 | 0.00 | 2.02 | 0.159 | 0.02 |

| Moment*Music | Condition*Music | Mom*Cond*Mus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(1,88) | p | np2 | F(1,88) | p | np2 | F(1,88) | p | np2 | |

| Positives | 0.16 | 0.690 | 0.00 | 1.14 | 0.288 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.409 | 0.01 |

| Negatives | 0.55 | 0.462 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.651 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.487 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blasco-Magraner, J.S.; Marín-Liébana, P.; Hurtado-Soler, A.; Botella-Nicolás, A.M. The Impact of the Soundscape on University Life: Critical Music Education as a Tool for Awareness and Transformation. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050600

Blasco-Magraner JS, Marín-Liébana P, Hurtado-Soler A, Botella-Nicolás AM. The Impact of the Soundscape on University Life: Critical Music Education as a Tool for Awareness and Transformation. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):600. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050600

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlasco-Magraner, José Salvador, Pablo Marín-Liébana, Amparo Hurtado-Soler, and Ana María Botella-Nicolás. 2025. "The Impact of the Soundscape on University Life: Critical Music Education as a Tool for Awareness and Transformation" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050600

APA StyleBlasco-Magraner, J. S., Marín-Liébana, P., Hurtado-Soler, A., & Botella-Nicolás, A. M. (2025). The Impact of the Soundscape on University Life: Critical Music Education as a Tool for Awareness and Transformation. Education Sciences, 15(5), 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050600