Abstract

Globalization enhances communication among people from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. As cultural artifacts, English language teaching textbooks are crucial media for learners’ intercultural education, especially under the concept of English as a lingua franca. This study investigated the cultural elements in Chinese university English textbooks via the approach of content analysis. Specifically, a set of Chinese English language teaching textbooks was selected as the sample and the audio and video materials were transcribed into texts as the data. The results were displayed by the counts of cultural elements. The data revealed that international cultures and source cultures were highlighted, and the textbooks were not oriented toward native-speakers’ English. Moreover, the distribution of cultural categories across the textbooks remains imbalanced, with cultural products occupying the largest proportion, and cultural perspectives displayed the least. This is mainly attributed to the fact that cultural perspectives are implicit cultures under the surface of the iceberg, and notably, they are sporadically reflected by the cultural products, practices, and persons. The findings provide suggestions that writers include balanced cultural elements in compiling English language teaching textbooks, and teachers scrutinize cultural representation and design intercultural activities.

1. Introduction

As globalization progresses, English has emerged as a global language. It is understood as the intensification of global social relations that connect distant localities (Giddens, 1990). Globalization facilitates English as a Lingua Franca (ELF), namely, the use of English among speakers of different native languages, for whom English serves as the preferred and often the sole medium of communication (Seidlhofer, 2011). This challenges the traditional dominance of native-speaker norms in various language teaching aspects (Baker, 2015). It is recommended that teaching materials be selected with careful consideration in the entire learning process under ELF perspectives (Tishakov & Tsagari, 2022). Kramsch and Vinall (2015) also claimed that the instruction and acquisition of culture are intrinsically connected to language education, which has been intensified in the contemporary globalized context. This demonstrates that the role of English has been reconsidered across language teaching practices. In this context, the textbook has likewise undergone reevaluation. As “windows to the world” (Risager, 2021, p. 12), textbooks are essential to the fulfillment of the socially transformational objectives of language education (Weninger & Kiss, 2013), especially in the ELF context. ELF perspectives prompted questions about ELT learning materials: “Is the world’s English reflected in ELT materials?”; “When are the local voices adequately represented in the content of English textbooks?” (Siqueira, 2015). Moreover, ELF serves as a facilitator in language learning (Giannakou & Karalia, 2023). Therefore, the challenge for ELT is designing materials that facilitate learners’ development as competent users of English as a lingua franca.

Not only serving as linguistic resources for English teaching and learning, ELT textbooks are also cultural artifacts (Apple & Christian-Smith, 1991; Gray, 2010). Particularly, textbooks have become a medium for the manifestation of cultural values, attitudes, and even stereotypes or misunderstandings, as they serve as an important source of cultural information in second-language teaching (Canale, 2016). Much of the research has focused on evaluating how and what kind of culture is portrayed in second-language textbooks (e.g., Gray, 2010, 2013; Uzum et al., 2021). Studies have pointed out the problems of extensive focus on Western cultures in English textbooks (Matsuda, 2002; Shin et al., 2011; Bowen & Hopper, 2023), echoed by scholars who advocated that cultural content in English language teaching materials should meet learners’ communication needs in different contexts of use (McKay, 2002; Sharifian, 2009). Under such circumstances, Si (2020) argues that an investigation into the integration of ELF in ELT materials is required in the field of English teaching and learning. In China, after the introduction of the overseas English textbook evaluation system, research on China-produced and China-consumed English textbooks began to be the trend (Jia, 2022). However, studies on ELT textbooks from ELF perspectives are limited. For instance, Liu et al. (2021) examined 10 sets of English textbooks used in Chinese universities between 2010 and 2015 via corpus methods, and the findings revealed that these textbooks show little interest in Chinese culture. Lu et al. (2022) also confirmed that Chinese culture tends to be underrepresented in Chinese senior high school textbooks. Although they provide implications for textbook culture analysis, there is a need for a panoramic view of cultural representations. Additionally, what remains insufficiently studied is the cultural representations in Chinese ELT textbooks after 2020, especially in tertiary education.

In China, learning English is regarded as meaningful for comprehending different cultures as well as facilitating cultural exchanges between China and other countries (The National College Foreign Language Teaching Advisory Board, 2020). To enhance English learning nationwide, the Ministry of Education (MoE) of China (MoE, 2020) has implemented many initiatives that emphasize Chinese cultural and universal cultural aspects in English textbooks. These policies underscore the need to understand the various elements of culture that exist in Chinese ELT textbooks. The present study set out to examine the cultural countries and categories (products, practices, persons, and perspectives) in Chinese university ELT textbooks under the framework of ELF. The cultural categories provide a framework for culture description with respect to teaching practices to students (Moran, 2009). They are applicable to textbook analysis for pedagogic significance.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The ELF and ELT Textbooks

Globalization is a multidimensional process that integrates economic, educational, social, and cultural aspects, thereby fostering new interconnections and significant transformations. English serves as a lingua franca (ELF), facilitating communication among diverse populations for whom it is not their first language (Seidlhofer, 2004). Seidlhofer (2011) then emphasized that ELF is “often the only option” (p. 7) for these people. In contrast to the approach taken in English as a foreign language (EFL), which seeks to pursue non-native English speakers’ (NNESs’) linguistic performance by modeling native English speakers (NESs), ELF provides a framework for understanding the linguistic outcomes generated by NNESs in intercultural communication (Jenkins, 2015).

ELF researchers challenge a traditionally essentialist approach to language, community, and culture, which posits them as fixed entities presumed to be closely interconnected, with a specific language representing a distinct community tied to a particular nation and culture. The term “language” is not simply a series of codes; rather, it is a situated practice, as viewed from the perspective of an ELF speaker (Baker, 2015). ELF encourages the examination of how ELF is linked with cultural diversity. The presumption that ELF users should conform to established norms, often those of native English speakers (NES), should be reconsidered.

As Alptekin (2002) has challenged NES, a new model of English teaching that values ELF should be promoted. Responding to it, teaching within the ELF framework should aim to equip learners with the skills to communicate effectively in English across contexts involving individuals from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds, which also means cultural diversity is emphasized (Galloway, 2017). However, Jenkins (2012) argues that textbooks that employ a more ELF-oriented approach remain relatively rare. Since textbooks typically function as learners’ language inputs and the basis of classroom language practices (Richards, 2001), whether the contents of ELT textbooks are under the ELF perspective needs to be reconsidered. Thus, the integration of the ELF perspective into teaching materials is applicable to ELT teaching and learning practices.

Not only serving as linguistic resources for English teaching and learning, ELT textbooks are also cultural artifacts (Apple & Christian-Smith, 1991; Gray, 2010). For textbook study, this seems as a consensus. It is then echoed by Risager (2020), who posits that textbooks are “windows to the world” (p. 1). Chinese policy and pedagogical guidelines advocate the cultivation of students as interculturally competent users of language. To prepare students as users in an ELF context, diverse cultures should be incorporated into ELT textbooks.

2.2. Cultural Representation in Language Textbooks

Textbook culture presentation is a decision, as Curdt-Christiansen and Weninger (2015) observe, and deals with the inclusion or exclusion of individuals depicting English learners’ communities. These reflect the users and owners of the English language, displaying information regarding who speaks English, as well as how, when, and where they speak English. Azimova and Johnston (2012) conclude that representation is inherently selective and advocate that language textbooks should authentically embody the sociolinguistic, sociocultural, and ethnic diversity of the source cultures. Language textbooks, especially, are influential tools of representation that shape learners’ perceptions of self, others, and the dynamics between them.

Several studies focused on the cultural representations of language textbooks, with various languages (Canale, 2016; Risager, 2020; Uzum et al., 2021). Some of the research findings (e.g., Matsuda, 2002; Siqueira & Matos, 2019) show that language textbooks present an uncritical view of target cultures. In other words, textbooks tend to present an Anglo-American culture of the target-language world. They make symbolic references to NNESs’ cultures and ignore the diverse cultures of these communities. Learners are able to access target communities but fail to critically reflect on their own cultures when relating them to others, particularly in the context of ELF. These studies illuminated cultural representations in English textbooks through diverse analytical lenses, offering insights into their educational impact, and implications for teaching and publishing practices.

A notable example of cultural representations in textbooks is Risager (2020), who conducted a comprehensive analysis of a selection of six different language textbooks that are used in Denmark. It proposes five approaches: “national studies, citizenship education, cultural studies, postcolonial studies, and transnational studies, each with a distinct focus” (p. 11). The research aims to explore how culture, society, and global perspectives are represented, as well as the methods of intercultural learning through textbooks in society. In her view, textbook representations often pose issues related to hierarchical structures and cultural homogenization, hindering the enhancement of learners’ intercultural competence. It can be inferred that what cultures are exposed to learners in ELT textbooks have an influence on shaping their worldviews, values, and beliefs. In China, ELT textbooks undertake the responsibility to foster students’ cultural sensitivity, which is also in alignment with the Chinese government’s policy on textbook guidelines.

A few studies have been conducted that employ a cultural analysis of ELT materials utilized in China (e.g., Lee & Li, 2019; Li et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2022; Si, 2020; Xiong & Qian, 2012). Liu et al. (2021) examined 10 sets of English textbooks used in Chinese universities between 2010 and 2015 via corpus methods, and the findings revealed that these texts are dominated by American and British cultures, while those of the Outer and Expanding Circles are entirely ignored, and these textbooks show little interest in Chinese cultures. Lu et al. (2022) conducted a case study employing content analysis to examine the cultural representations in two English language textbook series used in senior high schools in China. The results support the findings of Liu et al. (2021) that the Inner-Circle countries are dominant, while Chinese culture tends to be underrepresented. Several studies have conducted comparative analyses across different regions, such as China and Germany (Zhang & Su, 2021) and mainland China and Hong Kong (Lee & Li, 2019), with a primary focus on cultural representations in English textbooks used in primary and secondary schools. Respectively, Lee and Li (2019) found that the mainland textbooks mainly focused on British culture. The study by Zhang and Su (2021) also indicates that Inner-Circle cultures continue to be held in higher status than those of the Outer and Expanding Circle countries. These studies focus on cultural elements represented in Chinese English textbooks from various aspects. The investigated textbooks are from high school (Lu et al., 2022) or the textbook comparison between China and other areas (Zhang & Su, 2021). As to the research methods, the corpus tool is also adopted in the textbook analysis of cultures (Liu et al., 2021). Although content analysis has been employed, the theoretical perspective is from cultural sustainability (Lu et al., 2022). Thus, relatively little is known about the cultural representations of Chinese tertiary-level ELT textbooks.

English Language Teaching (ELT) scholars have made recommendations for creating and using educational materials that are diverse and meanwhile, respect local cultures (McKay, 2012). The extant studies in China show a predominance of the native-English-oriented culture in the ELT textbooks (e.g., Liu et al., 2021). However, coursebooks should be defined as resources that are tailored to a specific local context, with the aim of adopting an ELF-aware perspective (Guerra et al., 2020). This perspective is characterized by the acknowledgment that the English language is utilized around the world in a variety of international contexts, involving both native speakers and non-native speakers. Textbooks need to present the English language in a diverse array of language forms and functions, reflecting a broad range of cultural practices (Sifakis et al., 2018). Therefore, further study needs to be conducted to have a deeper understanding of cultural elements in ELT textbooks.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Context

A few English language textbooks are considered to be primarily directed to English-speaking countries’ cultures, with the exception of others (e.g., Davidson & Liu, 2020; Moss et al., 2015; Yim, 2007). For the newly and officially issued English textbooks for university students in China, whether it is more inclusive of ELF-informed cultures or English-speaking countries’ cultures and how the categories of cultures are represented remains to be answered. As China’s policy advocates inclusivity of Chinese cultures, how it is implemented and reflected in Chinese university textbooks also has room to be further investigated.

China deems English as a lingua franca, which serves as a link between Chinese and the wider world (Zhang et al., 2022), and learning English is regarded as meaningful for comprehending different cultures as well as facilitating cultural exchanges between China and other countries (The National College Foreign Language Teaching Advisory Board, 2020).

To foster Chinese cultural learning, the MoE (2020) has implemented initiatives that emphasize Chinese culture and international cultural aspects integration into English textbooks.

Under this context, this study aims to investigate whether the cultural representations in the newly published university ELT textbooks are in alignment with the requirements of MoE initiatives (2020), and to what extent the cultures are represented and reflected in the status of English as a lingua franca. To achieve this aim, the following research questions are to be answered:

- (1)

- Which countries are represented in Chinese university ELT textbooks?

- (2)

- What cultural categories are represented in Chinese university ELT textbooks?

3.2. The Selected Textbooks

Purposive sampling could be applied to both qualitative and quantitative research (Tangco, 2007). According to Richardson (2009), purposive sampling is a valuable method for selecting cases rich in information, particularly in the context of in-depth issue investigation. Purposive sampling is applied to unique cases that are deemed to be highly informative. They are usually selected based on their characteristics, research questions, the study’s analytical framework, and emerging results (Riazi, 2016). Therefore, it means that purposive sampling is appropriate to be used in the cases that are especially informative.

Textbooks are “informative in that they inform the learner about the target language” (Tomlinson, 2012, p. 143) and are regarded as “windows to the world” (Risager, 2021, p. 12). The purposive sampling is used to have a deeper analysis of the ELT textbooks content, particularly their cultural representations. In the current Chinese educational background, one university English textbook series was purposefully chosen.

The most recent edition of them was published in 2021 by a prominent Chinese publisher. The selection of the current English language textbooks was primarily based on two key reasons.

Firstly, Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press (SFLEP hereafter) was selected for its authority in China, although various publishers are legally authorized for textbook publication. Founded in 1979, SFLEP is a leading national publishing house based within the Shanghai International Studies University (SISU) under the auspices of the Ministry of Education. In China’s publishing industry, SFLEP stands as one of the most influential foreign language publishing institutions, recognized for its pivotal role in shaping pedagogical resources and advancing cross-cultural academic exchange (Cao, 2022). Among the accolades it has garnered are “the National Outstanding Group Award of Textbook Management”, and “the National Outstanding University Press Award”. The institution’s mandate includes the publication of textbooks, reference works, applied foreign languages, and scholarly periodicals (Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, n.d.). SFLEP focuses on language research and meanwhile takes on the affordances from high-quality academic results from overseas, especially foreign language teaching and learning.

Secondly, they share certain common characteristics. In accordance with the regulations on textbooks proposed by MoE (2020) in China, the textbook series is designed to cultivate learners’ competencies in language ability, cultural awareness, as well as intercultural capabilities. The prefaces concur that they facilitate the acquisition of both Chinese culture and a range of foreign cultures by students. This pedagogical approach is designed to cultivate a sense of cultural identity among learners, whilst also fostering an understanding of the similarities and differences between diverse cultural contexts.

To ensure data credibility, the English textbooks chosen for investigation are composed of four textbooks entirely utilized among universities for non-English majors. Details of the textbook are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of Chinese University ELT textbooks.

3.3. Theoretical Framework

ELT-informed textbooks differ from EFL-informed ones, even though English is regarded as a foreign language in China due to historical and social reasons. EFL communication, fundamentally, concludes that NNESs (Non-Native English speakers) learn English aiming to communicate with NESs (Native English speakers) (Jenkins, 2015). However, in China, the fundamental objective of English language instruction is not the acquisition of standard English, but intercultural communication (MoE, 2020). Under this scope, the position and function of English experience some turns in the academic domain, from WE to ELF. ELF can be defined as “any use of English among speakers of different first languages for whom English is the communicative medium of choice”. (Seidlhofer, 2011, p. 7). It appears evident that the status of ELF has now been established, thereby giving rise to a deliberation concerning whether ELT should consistently adhere to Standard English as spoken by native speakers, or whether it should give consideration to the pedagogical implications of research pertaining to ELF (Jenkins, 2015). During this, the selection of materials to be utilized in a language classroom has emerged as a pivotal issue (Si, 2020).

The conceptual framework of the study is based on viewpoints proposed by Kachru (1992), Cortazzi and Jin (1999), and Moran (2009).

The model proposed by Kachru (1992) is a useful and influential one for describing English dissemination. This model divides World Englishes into three concentric circles: the Inner Circle, the Outer Circle, and the Expanding Circle. In particular, the Inner Circle is comprised of countries in which the majority of the population has English as its native language, as well as the primary language used in social interaction. In Inner-Circle countries, English is spoken as a native language. The USA, Britain, Ireland, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand are all examples of Inner-Circle countries (Kachru, 1992). In these countries, the English language is employed in a number of public domains, including government and administration, education, and broadcast media. For most of the population, it is also used in private sections like the family. It means that individuals in Inner-Circle countries could use English for all purposes as long as language use is needed in daily life (McKay, 2002).

Meanwhile, Cortazzi and Jin’s (1999) categories of “Target culture”, “Source culture”, and “International Culture” are also utilized.

As Kramsch (1988) inquired three decades ago, which cultures ought to be incorporated into language instruction? Cortazzi and Jin’s (1999) response to the question suggested the integration of three sources of cultural materials into English language teaching: the source culture, the target culture, and international culture. To illustrate, the source culture is the learners’ own culture, and the target culture is the native English-speaking culture. Moreover, international culture includes a wide variety of cultures where English is used as an international language. In the present study, the concept of international culture is examined through the exclusion of both source and target cultures.

With regard to the cultural category, the approach drew upon the conceptual framework of Moran’s (2009) theory of culture, which encompasses the cultural products, practices, perspectives, communities, and persons. Cultural products are defined as artifacts, both tangible and intangible, produced or adopted by members of a given culture. Such artifacts may include plants, clothing, and language. These elements constitute the most direct components of cultural instruction. Cultural practices include behaviors and interactions that members of a culture engage in individually or with others, such as Chinese tea-drinking rituals. Cultural perspectives display perceptions, beliefs, values, and attitudes that influence cultural products and cultural practices, such as the ideas of gender equality. Cultural communities refer to cultures that are divided according to ethnic groups, or small groupings, like deaf people. Cultural persons refer to people who embody a particular cultural group or community, like Beethoven (Moran, 2009).

In the current study, in addition to famous people, unknown or ordinary people are also seen as persons, but figures in fictional stories or on TV are regarded as cultural products (Yuen, 2011). Moreover, following the completion of the preliminary study, the present research incorporates cultural communities into cultural persons. This is due to the fact that the persons under examination in this study generally represent given communities.

3.4. Data Collection

The culture-related elements from the textbooks were extracted via content analysis. Holsti (1969) defines content analysis as a method for drawing inferences through the objective as well as systematic identification of particular message characteristics. It is also supported by Krippendorff (2004), who posits that it is a systematic and objective method for categorizing and summarizing texts. The content analysis method, utilized in existing studies of language textbooks (Asakereh et al., 2019; Keles & Yazan, 2020), was applied to identify the cultures depicted in the textbooks.

New Target College English Video Course (hereafter New Target), published by SFLEP, comprises four books. Each unit covers various sections, like “Lead-in”, “Listening as Comprehension-Task One”, “Listening as Comprehension-Task Two”, and “Critical Thinking”. For illustration, the latter three sections all contain videos or audio for listening tasks. For “Lead-in”, sometimes it also includes videos or audio for listening. The speaking tasks are based on the listening materials. All video and audio materials were transcribed into written texts for analysis, while visual elements—both within the videos and on the textbook pages—were excluded from the analytical scope.

The books under examination include 32 units, with each book including 8 units. The contents of each unit are around a given topic, such as Education: Crossing Borders, The Power of Listening.

As to the researchers, one of the writers’ interests is textbook analysis, and another researcher specializes in culture learning in second-language classes. Moreover, both of them are English language teachers who used the textbooks, providing insider insights into the cultural representations of these ELT textbooks. Thus, in the coding process, they have relatively more profound thoughts about cultural elements based on experiences. Nevertheless, to reduce bias, another expert teacher was invited to be the counselor if disagreements occurred.

Equipped with a predetermined illustrated codebook of the overarching framework, the two researchers separately coded the textbooks and reviewed the codes to ensure consistency across pages. Prior to commencing the textbook coding process, as a preliminary exercise for assessing coding consistency, the two authors collaboratively coded three units from Textbook 1. To illustrate, the two researchers first independently coded the cultural elements across the pages and recorded them in the spreadsheet. Upon the completion of this part, the percentage of agreements was calculated. The results of the preliminary study showed that 87% were consistent. Next, the discrepant part was discussed until an agreement was achieved. The rest of the coding was based on this discussion. To ensure accuracy as well as inter-coder reliability, both authors engaged in thorough discussions to attain a comprehensive understanding of the framework.

Data were collected and analyzed through the identification and quantification of explicit references to cultural elements, guided by the theoretical framework informed by the perspectives of Kachru (1992), Cortazzi and Jin (1999), and Moran (2009).

Concretely, the data were quantified by occurrences, with each reference to cultural elements considered as a unit of analysis. Namely, each instance of a product or the name of a person was seen as a unit of analysis. Moreover, for the same cultural item, such as Beijing opera, regardless of whether the occurrence of Beijing opera took place within the same text or across different texts, its recurrence was documented anew.

4. Findings

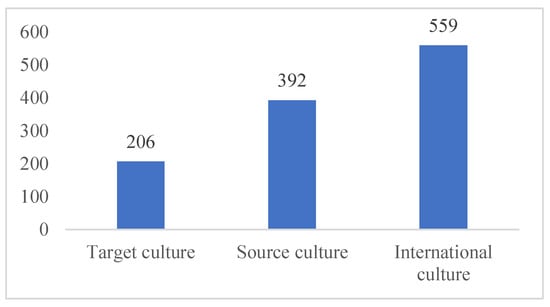

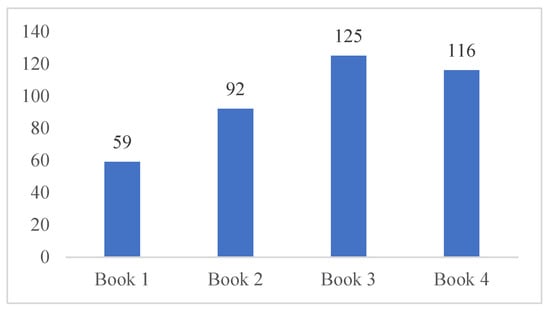

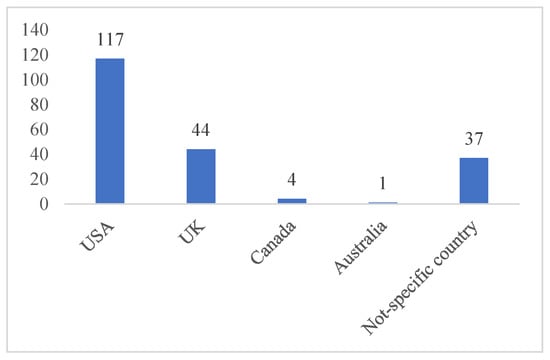

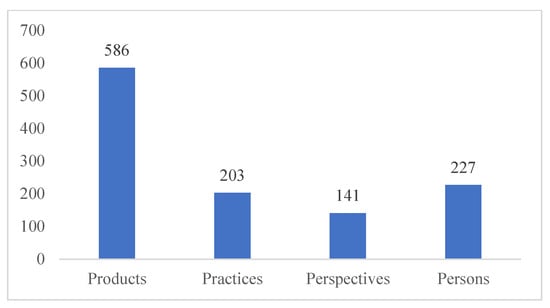

As presented in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, the analysis of the cultural content of the four textbooks was conducted with respect to the distribution of the countries and cultural categories that had been set out as objectives.

4.1. Categories of Countries

Figure 1 shows an overview of cultural representations of categories of countries in the textbooks. The coding results show that international cultures are the most frequently depicted cultural aspect, while target cultures are the least frequently portrayed. The quantity of international cultures is approximately equivalent to the aggregate number of target and source cultures. It is also well noted that the source culture (Chinese culture) has received significant coverage in the textbooks. Simultaneously, there is an illustration of some cultural elements, such as Twitter, although it has become a globalized social media, it is still regarded as a target culture because it originates in America, and the context is not oriented to the source or international culture. Similarly, the cultural item Harvard University is coded according to the occurrence of contexts, and each time it reoccurs, it is recorded anew.

Figure 1.

Categories of countries.

The distribution of source cultures is shown in Figure 2. In the current study, the source cultures refer to Chinese cultures. Every book of the investigated textbooks has covered Chinese culture, but there is no significant difference between the Chinese cultural representations.

Figure 2.

Source cultures across books.

The cultural content of inner-circle countries within the textbook, as illustrated in Figure 3, is predominantly American culture, followed by the UK, some not-specific countries, Canada, and Australia. Notably, American culture accounts for the largest proportion among the inner-circle countries, while Australian culture is the least frequently represented in the textbooks in the present study.

Figure 3.

Categories of inner-circle countries.

4.2. Cultural Categories

An imbalance in the representation of cultural categories is apparent, namely in relation to cultural products, cultural practices, cultural perspectives, and cultural persons, as evidenced by the following data shown in Figure 4. The following sections provide an exposition of the four cultural aspects, accompanied by pertinent examples.

Figure 4.

Cultural categories.

4.2.1. Cultural Products

As shown by Figure 4, the examined textbooks are dominated by cultural products (i.e., artifacts created to meet the needs of humans’ survival and development by a given culture). Specifically, a variety of cultural artifacts were represented in the textbooks, including famous cities and areas, travel destinations, art and literature, organizations, science and technology, food, media (including social media), language, education, religion, and history. It needs to be clarified that examples of famous cities and areas are California, Irvine, and London. Examples of travel destinations are Disneyland, Victoria Falls, and Shangri-La. Examples of art and literature are Dream of the Red Chamber, Journey to the West, Chu Ci, Li Sao. Examples of entertainment are Lightning McQueen, Inside Out, The Wolf Street. Examples of organizations are APEC, OECD, UN. Examples of science and technology are Apple, Pixar, and Haier. Examples of food are Cantonese cuisine, Chinese hot pot, and dim sum lunch. Examples of media (including social media) are Facebook, Sina Weibo, ask China and Twitter. Examples of languages are Ethnologue, Papua New Guinea languages, endangered languages. Examples of education are Big Five personality traits, US higher education, Harvard university. Examples of religion are Durham Cathedral, a Christian society, and polytheism. Examples of history are the information age, the digital age, Tang dynasty.

4.2.2. Cultural Practices

The data showed that cultural practices in the textbooks are represented second to the cultural products. These included daily life and lifestyles, like the 996 schedule, online classes, college life, intercultural communication. Festivals, such as the Dragon Boat festival, Cultural Heritage Day, Earth Day were integrated. Moreover, sports included Tai Chi, Kung Fu and the 1984 Summer Olympics. The textbooks also show explorations, including China’s Chang’e-4 lunar probe, Long March rockets. Beidou navigation satellite system. It also encompassed protection programs giant panda protection, protection of endangered animals, as well as political events, relating to the Belt and Road initiative, China’s labor law, and China’s education reform.

4.2.3. Cultural Perspectives

The third category entails the values or worldviews, such as educational equality, psychology of love and relationship, CPS (creative problem-solving), and ME culture, which believes each individual is responsible for their own well-being. WE culture, which prioritizes social ties and belonging to a larger group. In addition, the textbooks also encompass cultural perspectives associated with a given country, like Gross National Happiness (Every human being aspires for happiness in Bhutan), Wabi-sabi (a traditional Japanese concept of celebrating imperfection).

4.2.4. Cultural Persons

The cultural persons represented in the textbooks include three types: famous people, ordinary individuals, and communities who are the persons share common characteristics. Concurrently, figures in fictional stories or TV shows are regarded as cultural products (Yuen, 2011) and cultural persons in the present study all have biological characteristics. Famous people included athletes (e.g., Yao Ming Li Na), entrepreneurs (e.g., Bill Gates, Jack Ma, Warren Buffet), actors (e.g., Bruce Lee), artists (e.g., Toulouse-Lautrec, a French painter), writers (e.g., Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw, W.B. Yeats, Qu Yuan, Margaret Atwood. Politicians (e.g., Dragon King of Bhutan), characters in myths (e.g., narcissus). Regarding ordinary individuals, the textbooks involve Rebecca Darnell (a career consultant in the USA), Hawa Osman (a girl from Somalia), etc. As for communities, freshmen, senior citizens and Eskimos were introduced into the textbooks.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Representation of Countries in ELT Textbooks from ELF Perspective

Previous research has established that various ELT textbooks concentrated predominantly on cultural aspects specific to the NESs’ cultures, especially in the United States and England (Matsuda, 2002; Syrbe & Rose, 2016). This reflects EFL traditions that it is norm-dependent, targeting native-speakers’ lives, ideas, or behavioral models in English language teaching (Rose et al., 2020). However, under ELF perspectives and Chinese MoE (2020) textbook regulations, the current research revealed a heightened level of cultural inclusivity in representation via the approach of content analysis. The results implicated pedagogically the compilation of English textbooks, especially cultural items.

As to the countries in ELT textbooks, international cultures were found to represent the highest percentage in this study. The culturally international topics, such as Education in Somalia, World Hearing Day, smart city Mexico, localization, WE culture, Tamil language, were manifested in extensive coverage. Under this scope, it possesses the potential to cultivate an international vision by systematically integrating students’ diverse life experiences and cross-cultural representations within global contexts (Thongrin, 2018). The textbooks provide us with various cultural knowledge of others beyond our knowledge of self. This establishes a foundation for language learners to interact with different emergent socioculturally grounded communication patterns of reference informed by an understanding of culture in intercultural communication. In this way, English learners’ intercultural awareness can be cultivated through strategic engagement with English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) communicative scenario (Baker, 2011).

Regarding source culture, the analysis revealed a predominance of Chinese cultural representations in comparison to those from the Inner-Circle countries, as outlined by Kachru (1992), with Chinese cultural elements constituting 33% of total cultural references compared to 18% attributed to Inner-Circle Culture, thereby highlighting an inward emphasis within the examined materials. Conventionally, the cultural content incorporated within English Language Teaching (ELT) materials has been regarded as intimately related to the cultures of nations where English is spoken as a native language (McKay, 2002). This was challenged by Alptekin (2002), and it is not proper to provide learners with only a single culture. Moreover, ELT can effectively leverage locally relevant teaching content to enhance instructional outcomes. It is approved by Byram (1997), who posits that learners’ source culture can facilitate their understanding of diverse cultural practices, as unfamiliar phenomena are typically comprehended through the process of assimilating them to one’s own cultural context. In a similar vein, Cortazzi and Jin (1999) emphasize the significance of source cultural information, arguing that an understanding of one’s own culture enhances learners’ awareness of their cultural identity. Adaskou et al. (1990) demonstrated that learners’ engagement and motivation are enhanced when language instruction is connected to their lived experiences and cultural backgrounds. This knowledge not only facilitates the introduction of their culture to the broader world, but also enables more successful interactions with individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds.

As discussed above, the analyzed textbooks have highlighted international culture, as well as source culture. Notably, the textbooks have eschewed a ‘native-speaker’-dominated target culture. This is aligned with the ELF perspective that advocates cultural diversity in ELT (Baker, 2009). We advocate that the countries of culture should be represented more evenly. The cultivation of intercultural understanding serves as a critical pedagogical competency for English language learners, functioning as a skill for navigating the social dynamics embedded in globalized communication. Furthermore, it also conforms to the requirements of MoE (2020) that emphasize Chinese culture and international culture integration into English textbooks.

5.2. Cultural Category Representation

Concerning cultural categories, the representation of cultural products was most prominent across the textbooks. In the meantime, the other three aspects (cultural practices, persons, and perspectives) shared a relatively balanced representation. The cultural product predominance is consistent with Yuen’s (2011) study on ELT textbooks used in Hong Kong as well as Çelik and Erbay’s (2013) research in Turkey. A possible explanation for this consistency may be that students’ attention is more readily stimulated by popular cultural products like entertainment, travel, and cuisine than by abstract cultural perspectives such as philosophy. This is also supported by Yuen (2011), who claims that young people appear to be more attracted to the tourist’s stance, namely to cultural products. In regard to cultural persons, some playwrights like Shakespeare and George Bernard Shaw, Chinese poet Qu Yuan, Chinese novelist Mao Dun, and their respective works were introduced in the textbooks, which show a multi-genre and cross-national literary view. Meanwhile, the ethnical minority was also represented, such as Inuit and Eskimos. Each person is a distinct mix of communities and experiences, and all persons take on a particular cultural identity that separates them from other members of the culture (Moran, 2009). In the present study, the cultural persons and their identities indicate cultural versatility. Their integration complies with the requirements of MoE (2020).

Cultural perspectives were represented least across the texts. This result is possibly due to the following reasons: Cultural perspectives always have hidden property (Gu, 2002), and they are manifested in cultural practices. For example, in unit 1 of textbook 4, although the sentence “The fourth (Bhutanese) Dragon King reigned 34 years basing his decisions on all factors of Gross National Happiness” is classified into cultural practices, it advocates the perspective “Happiness is important for a country and its people”. This cultural practice can be applied to the classroom to stimulate students to identify the reasons for Gross National Happiness. On the other hand, the texts analyzed in the current study exclude the titles and quotations of each unit, but some of them are obvious in reflecting cultural perspectives, such as the title The Beauty of Cultural Diversity and the quotation “The way of great learning involves manifesting virtue, loving the people, and abiding by the highest good”. Which is from Chinese educator Confucius (551-479 BC). In the classroom, the listening and speaking tasks of this unit can be related to this quote to further foster students’ reflection. In addition to them, it is notable that the speaking tasks are always based on the listening tasks in the textbooks, aiming to motivate learners’ critical thinking on cultural practices. For example, there is an oral task: “According to the video, in ME cultures, people attach more importance to individuals, their responsibility for themselves, and their immediate family members. But for others in society, their responsibility is rather limited. What advantages and disadvantages can you find in ME cultures? Support your view with examples”. This task aims to inspire deeper interpretations of ME cultures for the learners. Another source of the finding is that cultural perspectives are implicit culture, which is beneath the iceberg, while cultural products, practices, persons, and communities are the explicit aspects above the surface (Moran, 2009). Under this scope, teachers need to design curriculum activities and improve teaching strategies to motivate students’ awareness and critical thinking on cultural perspectives based on other cultural aspects. Nevertheless, it is recommended that cultural perspectives should be given more attention in textbooks (Shin et al., 2011). The emphasis on them originates from teachers’ inspiration and efforts to internalize students’ cultural knowledge and values.

6. Conclusions

This study investigates cultural representations in Chinese university ELT textbooks. The findings indicate that international cultures and source cultures are valued, reversing the situation where the Inner-Circle cultures are dominated. Specifically, each of the two categories accounts for a higher proportion than that of the target cultures. They portray a multicultural and multifaceted world visible to learners. This is in alignment with the requirements of MoE (2020) and also the ELF-informed principle for enhancing learners’ intercultural awareness. In regard to cultural categories, cultural products occupy the largest proportion, while cultural perspectives remain underrepresented across the sampled textbooks. Various reasons may lead to this situation, such as the nature of the perspectives as the implicit cultural aspects (Moran, 2009). Thus, as teaching materials users, teachers could design tasks, like cultural comparisons, to motivate learners’ deeper critical thinking to understand cultural phenomena and encourage them to examine the underlying factors, thereby shaping their cultural values and beliefs. There is also a need for textbook writers to include well-balanced cultural content in the compilation of ELT textbooks. More specifically, the implicit cultural perspectives should be given more proportion. Furthermore, both the local and global cultures should be taken into account for the textbook complication. However, this study is limited by representativeness because only one series of books was under investigation. Nevertheless, the findings of the current study have implications for the cultural aspects represented in the ELT textbooks. The future study could incorporate more different types of ELT textbooks, such as primary or middle school textbooks. Moreover, for the textbook evaluation, teachers’ and students’ use is also crucial for ELF dissemination and cultural inclusion. Accordingly, further work needs to be conducted to explore pedagogical strategies for optimizing the incorporation of cultural elements within textbooks in classroom teaching practice. For instance, empirical studies of textbook use in classroom settings, as well as learners’ or teachers’ perceptions of language textbook cultural content, can be employed in further study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and N.R.M.N.; Methodology, H.Z. and N.R.M.N.; Investigation, H.Z.; Writing—original draft, H.Z.; Writing—review & editing, N.R.M.N.; Supervision, N.R.M.N.; Funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Humanities and Social Science Fund (grant number. 22Q186) from Education Department of Hubei Province, Teaching Research Fund (grant number. 2021437) from Education Department of Hubei Province.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adaskou, K., Britten, D., & Fahsi, B. (1990). Design decisions on the cultural content of a secondary English course for Morocco. ELT Journal, 44(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alptekin, C. (2002). Towards intercultural communicative competence in ELT. ELT Journal, 56(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apple, M. W., & Christian-Smith, L. K. (1991). The politics of the textbook. In M. W. Apple, & L. K. Christian-Smith (Eds.), The politics of the textbook (pp. 1–21). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Asakereh, A., Yousofi, N., & Weisi, H. (2019). Critical content analysis of English textbooks used in the Iranian education system: Focusing on ELF features. Issues in Educational Research, 29(4), 1016–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Azimova, N., & Johnston, B. (2012). Invisibility and ownership of language: Problems of representation in Russian language textbooks. The Modern Language Journal, 96(3), 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W. (2009). The cultures of English as a lingua franca. TESOL Quarterly, 43, 567–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W. (2011). Intercultural awareness: Modelling an understanding of cultures in intercultural communication through English as a lingua franca. Language and Intercultural Communication, 11(3), 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W. (2015). Culture and identity through English as a lingua franca: Rethinking concepts and goals in intercultural communication. De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, N. E. J. A., & Hopper, D. (2023). The representation of race in English language learning textbooks: Inclusivity and equality in images. TESOL Quarterly, 57(4), 1013–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Canale, G. (2016). (Re)searching culture in foreign language textbooks, or the politics of hide and seek. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 29(2), 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J. S. (2022). Foreign language publication in international communication: An example of Shanghai foreign language education press. Journal of Southeast University (Philosophy and Social Science), 24(12), 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S., & Erbay, Ş. (2013). Cultural perspectives of Turkish ELT coursebooks: Do standardized teaching texts incorporate intercultural features? Education and Science, 38(167), 336–351. [Google Scholar]

- Cortazzi, M., & Jin, L. X. (1999). Cultural mirrors: Materials and methods in the EFL classroom. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Culture in second language teaching and learning (pp. 196–219). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Curdt-Christiansen, X. L., & Weninger, C. (2015). Introduction. In X. L. Curdt-Christiansen, & C. Weninger (Eds.), Language, ideology and education: The politics of textbooks in language education (pp. 1–9). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, R., & Liu, Y. C. (2020). Reaching the world outside: Cultural representation and perceptions of global citizenship in Japanese elementary school English textbooks. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 33(1), 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, N. (2017). ELF and ELT teaching materials. In J. Jenkins, W. Baker, & M. Dewey (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of English as a lingua franca (pp. 468–480). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakou, A., & Karalia, K. (2023). Teaching the Greek language in multicultural classrooms using English as a lingua franca: Teachers’ perceptions, attitudes, and practices. Societies, 13(8), 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J. (2010). The branding of English and the culture of the new capitalism: Representations of the world of work in English language textbooks. Applied Linguistics, 31(5), 714–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J. (2013). Introduction. In J. Gray (Ed.), Critical perspectives on language teaching materials (pp. 1–16). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, L., Cavalheiro, L., Pereira, R., Kurt, Y., Oztekin, E., Candan, E., & Bayyurt, Y. (2020). Representations of the English as a lingua franca framework: Identifying ELF-aware activities in Portuguese and Turkish coursebooks. RELC Journal, 53(1), 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J. (2002). Language and culture. Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holsti, O. R. (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, J. (2012). English as a lingua franca from the classroom to the classroom. ELT Journal, 66(4), 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J. (2015). Global Englishes: A resource book for students (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, F. (2022). 30 years of evaluation and research on Chinese foreign language textbooks (1990–2020). Contemporary Foreign Languages Studies, (1), 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, B. B. (1992). The other tongue: English across cultures (2nd ed.). University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keles, U., & Yazan, B. (2020). Representation of cultures and communities in a global ELT textbook: A diachronic content analysis. Language Teaching Research, 27(5), 1325–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramsch, C. (1988). The cultural discourse of foreign language textbooks. In A. J. Singerman (Ed.), Toward an integration of language and culture (pp. 63–88). The Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, C., & Vinall, K. (2015). The cultural politics of language textbooks in the era of globalization. In X. L. Curdt-Christiansen, & C. Weninger (Eds.), Language, ideology and education: The politics of textbooks in language education (pp. 11–28). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. F. K., & Li, X. (2019). Cultural representation in English language textbooks: A comparison of textbooks used in mainland China and Hong Kong. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 28(4), 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Zeng, J., & Nam, B. H. (2023). A comparative analysis of multimodal native cultural content in English-language textbooks in China and Mongolia. SAGE Open, 13(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Zhang, L. J., & May, S. (2021). Dominance of Anglo-American cultural representations in university English textbooks in China: A corpus linguistics analysis. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 35(1), 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., Liu, Y., An, L., & Zhang, Y. (2022). The cultural sustainability in English as foreign language textbooks: Investigating the cultural representations in English language textbooks in China for senior middle school students. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 944381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, A. (2002). Representation of users and uses of English in beginning Japanese EFL textbooks. JALT Journal, 24(2), 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, S. L. (2002). Teaching English as an international language: Rethinking goals and perspectives. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, S. L. (2012). Teaching materials for English as an international language. In A. Matsuda (Ed.), Principles and practices of teaching English as an international language (pp. 70–83). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2020, January 7). Regulations on textbooks in tertiary education. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A26/moe_714/202001/t20200107_414578.html (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Moran, P. R. (2009). Teaching culture: Perspectives in practice. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, G., Barletta, N., Chamorro, D., & Mizuno, J. (2015). Educating citizens in the foreign language classroom: Missed opportunities in a Colombian EFL textbook. In X. L. Curdt-Christiansen, & C. Weninger (Eds.), Language, ideology and education: The politics of textbooks in language education (pp. 69–89). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Riazi, A. M. (2016). The Routledge encyclopedia of research methods in applied linguistics. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J. C. (2001). Curriculum development in language teaching. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, S. (2009). Undergraduates’ perceptions of tourism and hospitality as a career choice. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(3), 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risager, K. (2020). Language textbooks: Windows to the world. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 34(2), 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risager, K. (2021). Representations of the world in language textbooks. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, H., McKinley, J., & Galloway, N. (2020). Global Englishes and language teaching: A review of pedagogical research. Language Teaching, 54(2), 157–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidlhofer, B. (2004). Research perspectives on teaching English as a lingua franca. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 209–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidlhofer, B. (2011). Understanding English as a lingua franca. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press. (n.d.). Introduction. Available online: https://www.sflep.com/es/about-us/ (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Sharifian, F. (2009). English as an international language: Perspectives and pedagogical issues. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J., Eslami, Z. R., & Chen, W. C. (2011). Presentation of local and international culture in current international English-language teaching textbooks. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 24(3), 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J. (2020). An analysis of business English coursebooks from an ELF perspective. ELT Journal, 74(2), 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifakis, N., Lopriore, L., Dewey, M., Bayyurt, Y., Vettorel, P., Cavalheiro, L., Siqueira, S., & Kordia, S. (2018). ELF-awareness in ELT: Bringing together theory and practice. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 7(1), 155–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, D. S. P. (2015). English as a lingua franca and ELT materials: Is the “plastic world” really melting? In Y. Bayyurt, & S. Akcan (Eds.), Current perspectives on pedagogy for English as a lingua franca (pp. 239–257). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, D. S. P., & Matos, J. V. G. (2019). ELT materials for basic education in Brazil: Has the time for an ELF-aware practice arrived? In N. C. Sifakis, & N. Tsantila (Eds.), English as a lingua franca for EFL contexts (pp. 132–156). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Syrbe, M., & Rose, H. (2016). An evaluation of the global orientation of English textbooks in Germany. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 12(2), 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangco, M. D. C. (2007). Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 5, 147–158. Available online: https://ethnobotanyjournal.org/index.php/era/article/view/126 (accessed on 20 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- The National College Foreign Language Teaching Advisory Board. (2020). College English teaching guidelines. Higher Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thongrin, S. (2018). Integrating moral education into language education in Asia: Guidelines for materials writers. In P. W. Handoyo, M. R. Perfecto, L. V. Canh, & A. Buripakdi (Eds.), Situating moral and cultural values in the ELT materials: The Southeast Asian context (pp. 153–174). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tishakov, T., & Tsagari, D. (2022). Language beliefs of English teachers in Norway: Trajectories in transition? Languages, 7(2), 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, B. (2012). Materials development for language learning and teaching. Language Teaching, 45(2), 143–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzum, B., Yazan, B., Zahrawi, S., Bouamer, S., & Malakaj, E. (2021). A comparative analysis of cultural representations in collegiate world language textbooks (Arabic, French, and German). Linguistics and Education, 61(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weninger, C., & Kiss, T. (2013). Culture in English as a foreign language (EFL) textbook: A semiotic approach. TESOL Quarterly, 47(4), 694–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T., & Qian, Y. (2012). Ideologies of English in a Chinese high school EFL textbook: A critical discourse analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 32(1), 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, S. (2007). Globalisation and language policy in South Korea. In A. B. M. Tsui, & J. W. Tollefson (Eds.), Language policy, culture, and identity in Asian contexts (pp. 37–53). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, K. M. (2011). The representation of foreign cultures in English textbooks. ELT Journal, 65(4), 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Li, X., & Chang, W. (2022). Representation of cultures in national English textbooks in China: A synchronic content analysis. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45(8), 3394–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., & Su, X. (2021). A cross-national analysis of cultural representations in English textbooks used in China and Germany. SN Social Sciences, 1(4), 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).