1. Introduction

In today’s digital world, media multitasking, the practice of juggling multiple streams of content simultaneously, has become increasingly prevalent. This carries significant implications for cognitive processing, as research demonstrates the substantial negative effects of media multitasking on cognitive performance (

Clinton-Lisell, 2021;

Delello et al., 2016;

Medina, 2009;

Mokhtari et al., 2009;

Mokhtari et al., 2015). Specifically concerning reading, a meta-analysis by

Clinton-Lisell (

2021) found that multitasking negatively impacts reading comprehension overall (effect size g = −0.28), with the detriment being particularly pronounced when the reading time is limited (g = −0.54). Furthermore, even when comprehension is not significantly impaired (e.g., in self-paced reading), multitasking consistently leads to significantly longer reading times (g = 0.52), indicating reduced efficiency (

Clinton-Lisell, 2021). Within broader academic contexts, media multitasking has also been linked to detrimental student outcomes (

May & Elder, 2018).

The documented cognitive costs and inefficiencies associated with media multitasking raise important questions for educators. Teachers’ reading practices warrant special investigation for several reasons. First, teachers serve as critical literacy models, and their own reading habits can directly influence their instructional approaches and, consequently, student outcomes (

Chen et al., 2024). Second, reading constitutes a primary means of ongoing professional development, especially in rapidly evolving fields, such as English as a foreign language (EFL) instruction, where staying current with methodological innovations is essential. Research has demonstrated that professional development in reading has significant effects on teacher knowledge (g = 0.947) and teaching practices (

Rice et al., 2024), making teachers’ reading habits particularly important for their professional growth. In a commissioned study on reading instruction in Morocco,

RTI International (

2015) evaluated the extent to which the official teacher-training curriculum aligns with current research on how children learn to read in Arabic. The study reviewed the instructional methods introduced to future teachers and assessed the adequacy of their preparation to teach reading effectively. The findings highlighted the need to enhance the curriculum to better equip preservice teachers with evidence-based strategies for reading instruction.

Understanding the impact of multitasking on teacher reading practices requires considering the changing nature of reading itself in the digital age. Different reading substrates (e.g., paper versus digital screens) possess distinct affordances that shape the reading experience (

Mangen & van der Weel, 2016). Furthermore, the influence of media multitasking might be moderated by variables such as teaching experience. For instance, more-experienced teachers might possess better-developed strategies for managing digital distractions (

Carrier et al., 2015). Contextual factors, such as school location (urban versus rural), could also play a role by influencing access to technology and norms surrounding its use during professional time. Research by

Lucas et al. (

2021) confirmed that both personal factors (age, experience, and attitudes) and contextual factors (infrastructure, institutional support, and technological access) significantly influence teachers’ digital practices and competence.

Research on information and communication technologies (ICTs) suggests their potential to support reading practices when implemented effectively. Studies indicate that digital technologies can contribute to the development of reading skills (

Fernandez Batanero et al., 2021). Additionally, research has documented specific literacy benefits associated with ICT use, including vocabulary building through tools such as online dictionaries and enhanced student engagement with reading materials (

Maduabuchi & Emechebe, 2016). These findings suggest that ICTs, when thoughtfully integrated, can complement rather than simply displace traditional reading practices.

The Moroccan EFL context provides a compelling setting for examining these issues. Educational policy in Morocco tends to emphasize English learning, placing high expectations on EFL teachers for continuous professional learning, much of which relies on reading. Concurrently, the country has undergone rapid digital transformation, with Internet penetration rising significantly from approximately 50% in 2010 to over 90% in 2024 (

DataReportal, 2023;

Statista, 2024), fostering an environment in which media multitasking behaviors among teachers may be prevalent.

Building on prior work exploring media multitasking’s general cognitive effects and reading habits among students and the public (e.g.,

Crain, 2018;

Mokhtari et al., 2009;

Delello et al., 2016;

May & Elder, 2018;

Murphy, 2021), a significant gap appears to exist in understanding how multitasking-related behaviors specifically affect teachers’ reading practices. Research focusing explicitly on EFL teachers’ academic and recreational reading in relation to multitasking remains limited, despite the crucial role these teachers play as literacy role models (

Chen et al., 2024) and the unique demands of their professional context, particularly within the evolving digital reading landscape (

Mangen & van der Weel, 2016).

Therefore, in this study, we examined the amount of time Moroccan EFL teachers report spending on academic and recreational reading, and the extent to which media multitasking, specifically involving television and Internet use, may interfere with or displace this reading time. We argue that media multitasking during reading may diminish both the time spent reading and the quality of reading, with potential negative impacts on teachers’ and students’ reading practices and academic outcomes. To investigate these issues, we surveyed teachers in Morocco about their time spent on reading, TV viewing, and Internet browsing, as well as their perceived levels of multitasking and its effects on their reading.

Three research questions guided our study.

To what extent do Internet use and TV viewing displace or interfere with the time participants report spending on academic reading?

To what extent do Internet use and TV viewing displace or interfere with the time participants report spending on recreational reading?

What differences exist in the displacement patterns between academic and recreational reading, and how are these patterns moderated by factors such as teaching experience, school type, and specific multitasking activities?

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a quantitative research design using an online time-diary survey to investigate the media multitasking habits and reading practices of Moroccan EFL teachers. The following sections describe the participants, survey instrument, data collection procedures, and data analysis techniques.

3.1. Participants

To investigate the media multitasking habits and reading practices of Moroccan EFL teachers, we recruited participants from various educational settings across Morocco. We used a combination of purposive and snowball sampling techniques, reaching potential participants through professional networks, teacher associations (e.g., the Moroccan Association of Teachers of English [MATE]), and social media platforms involving teachers of English in Morocco. The initial recruitment targeted a diverse sample across experience levels, school types, and geographical regions to ensure the representation of the broader Moroccan EFL teaching population.

Out of the 1160 teacher respondents, 700 completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 60.34%. Before arriving at this final sample, we applied several exclusion criteria to ensure data quality and participant eligibility. Specifically, we eliminated the respondents who (a) did not consent to participate, (b) completed less than 27% of the survey, (c) had missing data on key variables, or (d) did not meet the inclusion criteria. The multi-step exclusion process resulted in the removal of 460 entries, leading to the final sample of 700 participants.

Participants’ ages ranged from 22 to 58 years (M = 35.6; SD = 7.8), with the majority (55.57%) falling within the 31–40 age group. In terms of gender, 61.29% were male, 26.14% were female, and 12.57% did not report their gender. Regarding teaching experience, 44.7% had 0–5 years of experience, 32.17% had 6–10 years, and 22.57% had 11–15 years. The distribution of school locations was balanced, with 59% of participants teaching in urban/suburban areas and 40.14% in rural settings. This diversity among the participants enabled meaningful comparisons across various teacher profiles and contexts. As an incentive for participation, all respondents who completed the survey were entered into a drawing for one of two USD 25 gift cards.

3.2. Time-Diary Survey

The data for this study were collected using an online time-diary survey administered through Qualtrics. Time-diary surveys are a well-established method for gathering detailed, accurate data on individuals’ daily activities and time-use patterns (

Juster et al., 2003;

Kaufman & Lindquist, 2019). In contrast with traditional retrospective surveys, which ask participants to estimate their time use over extended periods, time-diary surveys focus on shorter, more recent time frames (e.g., the previous day) to minimize recall bias and improve data quality (

Nie & Erbring, 2002;

Robinson & Goodbey, 1999).

The design of our time-diary survey was informed by previous studies, particularly

Nie and Erbring’s (

2002) “6-Hour Time Diary” method, which has been widely used to investigate media use and time allocation. This approach involves dividing the day into discrete periods and asking participants to report on their activities during each period, providing a comprehensive picture of their daily routines and behaviors.

The use of an online survey platform allowed for efficient data collection and automated timestamping of responses, reducing the risk of data entry errors and increasing the reliability of the data (

Bonke & Fallesen, 2010;

Kaufman & Lindquist, 2019). Prior to the full-scale data collection, the survey was piloted with a group of five EFL teachers to assess its clarity, comprehensiveness, and ease of use. Based on the feedback from the pilot testing, minor revisions were made to the wording and order of some questions to improve the overall flow and coherence of the survey.

The survey comprised five main sections: (1) demographic information, including age, gender, teaching experience, and school characteristics; (2) access to and use of various media devices; (3) time spent on different activities, including both recreational and academic reading; (4) multitasking behaviors during reading activities; and (5) perceived displacement of reading time due to other media activities. This comprehensive approach enabled us to examine not only the frequency and duration of reading and media use but also the complex interactions between these activities.

3.3. Measures

The following variables were included in the analysis to examine their association with the displacement of time during reading for fun/recreational reading and academic reading:

Displacement of time (rf_disp; ra_disp) [outcome variable]: participants’ self-reported displacement of time allocated to recreational reading (rf_disp) and academic reading (ra_disp). Participants indicated the extent of time displacement using a categorical scale as “No, not at all”, “Yes, some”, or “Yes, a lot”, indicating no displacement of time, moderate displacement of reading time, or substantial displacement of reading time, respectively.

School type (sch-type): Indicated whether the school was in an urban/suburban or rural area.

Time of reading (rf_time; ra_time): The time of the day when participants engaged in reading, categorized as 6:00 a.m.–11:59 a.m., noon–6:00 p.m., 6:00 p.m.–11:59 p.m., or midnight–5:59 a.m.

Length of reading (rf_length; ra_length): The duration of the reading activity, categorized as less than 30 min, 30–59 min, 60–89 min, 90–119 min, or 2 h or more.

Teaching experience (experience): The number of years of teaching experience, categorized as 0–5 years, 6–10 years, or 11–15 years.

Engaging in professional development while reading for fun (rf_pd): The extent to which participants engaged in professional development activities while reading for fun, rated on the same scale as the multitasking activity.

Multitasking activities: The extent to which participants engaged in various activities while reading, rated on a scale of “Never”, “A little of the time”, “Some of the time”, or “Most of the time”. These activities included the following:

- ○

Watching TV (rf_tv; ra_tv);

- ○

Listening to music (rf_music; ra_music);

- ○

Talking on the phone (rf_talk_phone; ra_talk_phone);

- ○

Playing video or online games (rf_onl_game; ra_video_game);

- ○

Using social networks (rf_soc_network; ra_soc_network).

The variables included in the models for reading for fun or recreational reading (rf_) and reading for academic purposes (ra_) slightly differed based on the results of chi-square tests, which indicated the presence of significant associations between these variables and the displacement of time. While the specific variables included in each model may have differed, it is important to note that the chi-square test only indicated the presence of significant associations and did not provide information about the nature or direction of these associations.

4. Analytical Procedures

The data analysis for this study involved a combination of descriptive statistics, bivariate tests, and ordinal logistic regression modeling to address the research questions. All analyses were conducted using the R statistical software [R version 4.4.3 (2025-02-28 ucrt)] (

R Core Team, 2025).

First, we generated descriptive statistics and visualizations to explore the distribution of key variables and participant characteristics. This included calculating frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations for demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, and teaching experience) and the main study variables related to reading habits and media use.

Next, we conducted bivariate analyses to examine the relationships between participant characteristics, media use variables, and the outcome variable of time displacement. Specifically, we used chi-square tests to assess whether there were significant associations between categorical variables such as gender, teaching experience, school type, and time displacement for academic and recreational reading. For continuous variables (e.g., time spent on different activities), we used t-tests or ANOVA to compare means across groups after checking for normality assumptions.

To identify potential predictors of time displacement and assess their relative importance, we employed ordinal logistic regression modeling. This approach was chosen due to the ordinal nature of the outcome variables, which were measured on a three-point scale (No, not at all; Yes, some; Yes, a lot). The predictor variables included in the models were participant demographics, school characteristics, and media use variables.

Before fitting the regression models, we conducted preliminary analyses to check for multicollinearity among the predictor variables. This step involved examining bivariate correlations and variance inflation factors (VIFs) to ensure no strong linear dependencies distorted the model results (

Dormann et al., 2013;

Midi et al., 2010). All variables showed acceptable VIF values (below 5), indicating no problematic multicollinearity.

The ordinal logistic regression models were fitted using the {polr} function from the ‘MASS’ package in R (

Venables & Ripley, 2002). Model fit was assessed using deviance statistics and the Akaike information criterion (AIC). We also examined the proportional odds assumptions to ensure that the effect of each predictor was constant across all levels of the outcome variable using the Brant test. Although the omnibus test showed some deviations from the proportional odds assumption, an examination of individual predictors indicated these violations were not severe enough to invalidate the models.

The final models were interpreted in terms of odds ratios, which represented the change in the odds of being in a higher category of time displacement for a one-unit increase in the predictor variable, holding all other variables constant. To further explore the differences in time displacement between academic and recreational reading, we conducted additional analyses comparing the distribution of displacement categories and the significance of predictor variables across two domains. We also calculated pseudo-R2 values to estimate the overall explanatory power of each model.

All statistical tests were performed at a significance level of 0.05, and confidence intervals were reported where appropriate. Missing data were handled using listwise deletion, as the proportion of missing values was relatively low (<5%), and there was no evidence of systematic patterns of missingness. This approach was chosen over imputation methods to maintain the integrity of the data without introducing potential biases from imputation.

5. Results

5.1. Participant Characteristics and Key Variables

The detailed demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in

Table 1. In addition, several key variables related to reading habits and multitasking activities were examined. The time of reading for both fun and academic purposes varied across participants, with the most common times being noon–6:00 p.m. (39.14% for fun; 40.86% for academic), followed by 6:00 p.m.–11:59 p.m. (32.29%) for fun, but 6:00 a.m.–11:59 a.m. (28.71%) for academic reading. Midnight–5:59 a.m. was the least common reading time for both recreational (5%) and academic purposes (2.71%).

The length of reading sessions varied notably between recreational and academic purposes. For recreational reading, most reading sessions lasted 30–59 min (48.57%), followed by 60–69 min (22.14%), less than 30 min (13.43%), 2 h or more (8.14%), and 90–119 min (7.57%). In contrast, academic reading sessions demonstrated a different distribution, with a significant proportion lasting 2 h or more (46.71%). Other durations for academic reading included 30–59 min (23.21%), less than 30 min (15%), 60–89 min (9.43%), and 90–119 min (5.86%). Additionally, 45.57% of participants reported engaging in some professional development activities while reading for fun, followed by 26.34% who did a little of the time, 17.22% most of the time, and 4.34% who never engaged in professional development activities while reading for fun.

5.2. Research Question 1: To What Extent Do Internet Use and TV Watching Displace or Interfere with Time Participants Report Spending on Academic Reading?

To investigate the potential displacement or interference of Internet use and TV watching on the time participants reported spending on academic reading, we conducted chi-square tests to identify variables that had a statistically significant association with the reported level of displacement. The results indicated that teachers’ years of experience (χ2(4) = 11.23; p = 0.024) and school type (χ2(2) = 8.20; p = 0.017) were significantly associated with the reported displacement of time from academic reading.

In terms of multitasking activities, the chi-square tests revealed that the time spent reading for academic purposes (ra_time) (χ2(6) = 37.01; p < 0.001); the length of reading sessions (ra_length) (χ2(8) = 17.33; p = 0.026); watching TV (ra_tv) (χ2(6) = 24.02; p < 0.001); listening to music (ra_music) (χ2(6) = 22.76; p < 0.001); and talking on the phone (ra_talk_phone) were all significantly associated with the reported displacement of time from academic reading.

To further explore the combined impact of these variables on time displacement in academic reading, we conducted an ordinal logistic regression analysis. The model included the variables that indicated significant associations in the chi-square tests. The results of the regression analysis are presented in

Table 2.

The model’s goodness of fit was assessed using the deviance statistics (1172.27) and the Akaike information criterion (AIC) (1226.28), which indicated an improvement over the null model (deviance = 1323.32; AIC = 1327.32). The model explained approximately 11.4% of the variance in displacement of time from academic reading according to McFadden’s pseudo-R2 (0.114).

The results reveal several significant predictors of displacement from academic reading. Teachers with 6–10 years (β = −0.58, SE = 0.18, and p = 0.002) and 11 and more years of experience (β = −0.49, SE = 0.22, and p = 0.025) had statistically lower log odds of reporting higher levels of displacement from academic reading compared with those with 0–5 years of experience. This indicates that more-experienced teachers were less likely to experience displacement, with an odds ratio of 0.56 (95% CI [0.39, 0.80]) and 0.61 (95% CI [0.40, 0.94]), respectively. To interpret these odds ratios, teachers with 6–10 years of experience had approximately 44% lower odds of reporting higher levels of displacement compared with novice teachers.

Teachers working in urban or suburban schools exhibited higher log odds (β = 0.35; SE = 0.17) of reporting greater displacement than their counterparts in rural schools, with an odds ratio of 1.42 (95% CI [1.02, 1.96]). This means the urban/suburban teachers had 42% higher odds of reporting greater displacement from academic reading compared with rural teachers.

Additionally, engaging in academic reading during the evening (6:00 p.m.–11:59 p.m.) was associated with lower log odds of reporting higher displacement (β = −0.78; SE = 0.22) relative to morning reading (6:00 a.m.–11:59 a.m.), with an odds ratio of 0.46 (95% CI [0.30, 0.71]). This implies that evening reading sessions were associated with a 54% reduction in the odds of experiencing higher levels of displacement compared with morning sessions.

In contrast, frequently watching TV while reading (“most of the time”; β = 0.98 and SE = 0.42) was linked to higher log odds of reporting displacement compared with never watching TV, with an odds ratio of 2.65 (95% CI [1.16, 6.06]). This finding indicates that teachers who watched TV most of the time while reading for academic purposes had 2.65 times higher odds of experiencing greater displacement compared with those who never watched TV during academic reading.

Interestingly, listening to music “a little of the time” while reading for academic purposes was associated with lower displacement (β = −0.83, SE = 0.42, and p = 0.046), with an odds ratio of 0.44 (95% CI [0.19, 0.99]). Playing video games “most of the time” was also significantly associated with higher displacement (β = −0.86, SE = 0.44, and p = 0.049), with an odds ratio of 0.42 (95% CI [0.18, 1.00]).

The Brant test for the proportional odds assumption showed some violations (χ2(25) = 51.84; p = 0.001), primarily for the time of reading variables. However, the examination of individual predictors indicated these violations were not severe enough to invalidate the model.

5.3. Research Question 2: To What Extent Do Internet Use and TV Watching Displace or Interfere with Time Participants Report Spending on Recreational Reading?

To examine the factors associated with the displacement of time from recreational reading among Moroccan EFL teachers, we conducted chi-square tests and an ordinal logistic regression analysis. The chi-square tests revealed significant associations between the level of displacement and several variables: school type (χ2(2) = 22.34; p < 0.001); timing of recreational reading (rf_time) (χ2(6) = 17.63; p = 0.007); and time spent on social networks (rf_soc_network) (χ2(6) = 18.44; p = 0.005). In addition, watching TV (rf_tv) (χ2(6) = 22.60; p < 0.001); listening to music (rf_music) (χ2(6) = 12.95; p = 0.04); engaging in professional development activities (rf_pd) (χ2(6) = 14.52; p = 0.02); talking on the phone (rf_phone) (χ2(6) = 13.40; p = 0.03); and playing online games (rf_onl_game) (χ2(2) = 16.13; p = 0.01) were each significantly associated with displacement.

An ordinal logistic regression analysis was then performed to further investigate these relationships (see

Table 3). The model fit was evaluated using the deviance statistic (1121.49) and the Akaike information criterion (AIC = 1177.49), indicating an improved fit relative to the null model (deviance = 1292.79; AIC = 1296.79). The model explained approximately 13.2% of the variance in displacement according to McFadden’s pseudo-R

2 (0.132).

The results reveal significant associations between certain predictor variables and the displacement from reading for fun. School type was found to be a significant predictor (β = 0.80, SE = 0.17, and p < 0.001), with an odds ratio of 2.23 (95% CI [1.59, 3.14]), indicating that teachers from urban/suburban schools were more than twice as likely to report higher frequencies of displacement compared with the teachers from rural schools. Teachers who read for fun during noon–6 p.m. reported significantly less distraction (β = −0.41, SE = 0.21, and p = 0.05) compared with the teachers who read during 6 a.m.–11:59 a.m., with an odds ratio of 0.66 (95% CI [0.44, 1.00]).

The duration of reading for fun showed a significant association with displacement. Specifically, teachers who reported reading for fun for 30–59 min (β = −0.55, SE = 0.26, and p = 0.020), with an odds ratio of 0.55 (95% CI [0.33, 091]), and those reading for 60–89 min (β = −0.78, SE = 0.30, and p = 0.008), with an odds ratio of 0.46 (95% CI [0.26, 0.82]), reported significantly less displacement compared with teachers who read for fun for less than 30 min.

In addition, teachers who reported watching TV “most of the time” while reading for fun experienced slightly higher displacement (β = 0.96, SE = 0.41, and p = 0.018), with an odds ratio of 2.61 (95% CI [1.18, 5.79]) compared with teachers who did not watch TV while reading for fun. Moreover, teachers who talked on the phone “some of the time” while reading for fun experienced significantly higher displacement (β = 0.74, SE = 0.37, and p = 0.044), with an odds ratio of 2.09 (95% CI [1.02, 4.27]) compared with teachers who did not talk on the phone. Similarly, compared with the teachers who did not use social network sites, those who reported using them “a little of the time” (β = −1.04, SE = 0.37, and p = 0.005), with an odds ratio of 0.36 (95% CI [0.17, 0.73]); “some of the time” (β = −0.83, SE = 0.37, and p = 0.023), with an odds ratio of 0.44 (95% CI [0.21, 0.89]); and “most of the time” (β = −0.90, SE = 0.42, and p = 0.030), with an odds ratio of 0.41 (95% CI [0.18, 0.92]) all reported significantly lower time displacement from reading for fun.

The Brant test for the proportional odds assumption showed minor violations (χ2(26) = 41.35; p = 0.029), but individual predictors generally satisfied the assumption, indicating the model was valid.

5.4. Research Question 3: What Are the Differences in Displacement of Time Allocated to Academic Versus Recreational Reading?

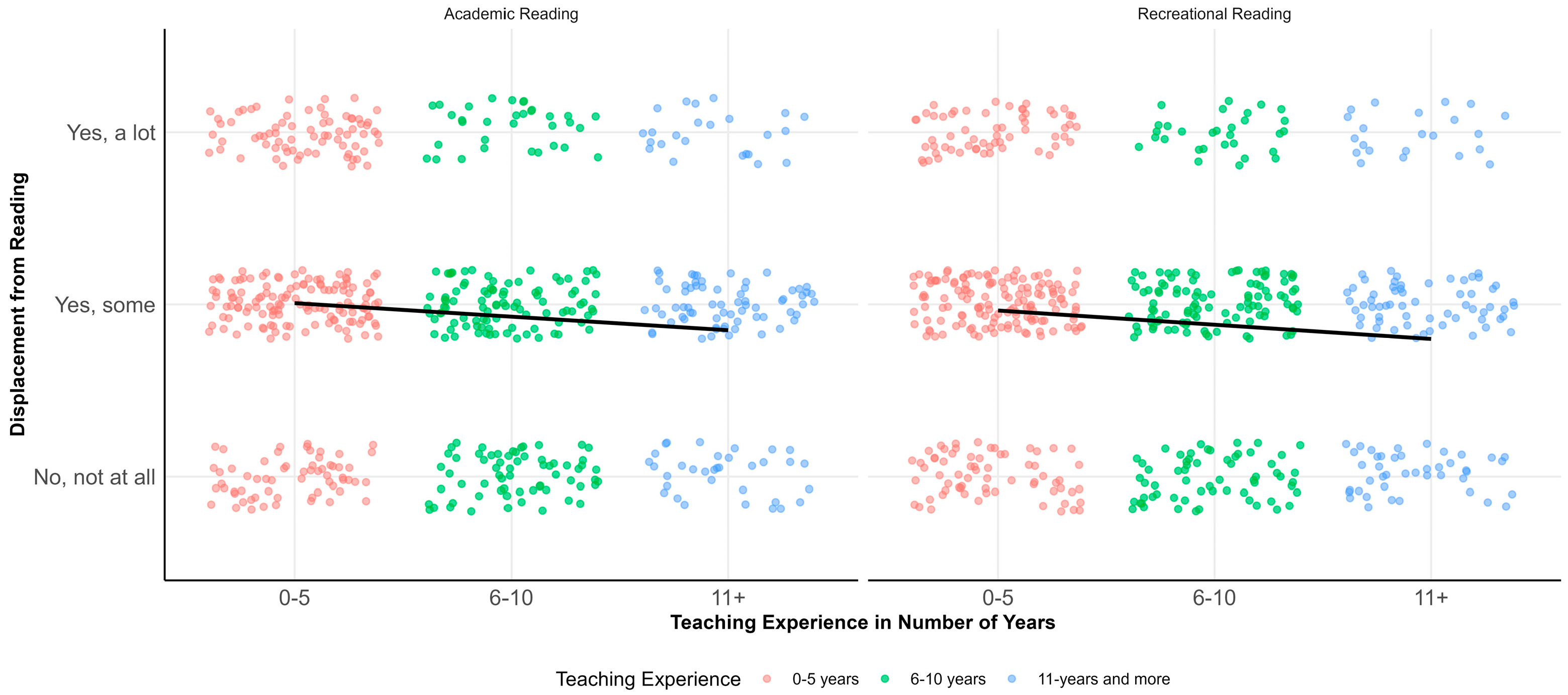

To examine differences in time displacement between academic and recreational reading, we compared the percentage of teachers reporting varying levels of displacement for each reading type and analyzed the significance and magnitude of predictors across models. The chi-square tests revealed that teaching experience was significantly associated with displacement in academic reading (χ

2(4) = 11.23;

p = 0.02), but not with recreational reading (χ

2(4) = 6.17;

p = 0.19). Despite this divergence in statistical significance,

Figure 1 shows a consistent trend: teachers with greater experience, particularly those with “11+ years,” tended to report lower levels of displacement than their less-experienced counterparts. This trend suggests that more-experienced teachers may be better equipped to manage the disruptive impact of media multitasking on their reading habits.

The ordinal logistic regression analyses (see

Table 2 and

Table 3) further clarified the differences in the predictors for academic and recreational reading. For academic reading, teachers with 6–10 years (β = −0.58, SE = 0.18, and

p = 0.002) and those with 11 or more years (β = −0.49, SE = 0.22,

p = 0.025) of experience had lower log odds of reporting higher displacement compared with teachers with 0–5 years of experience. Additionally, school type emerged as a significant predictor in both contexts, but with different effect sizes. Teachers in urban or suburban schools had higher log odds of displacement compared with those in rural schools, with this effect being substantially stronger for recreational reading (OR = 2.23; 95% CI [1.59, 3.14]) than for academic reading (OR = 1.42; 95% CI [1.02, 1.96]).

Differences also emerged regarding the timing of reading. For academic reading, engaging in reading between 6:00 p.m. and 11:59 p.m. was associated with lower log odds of displacement compared with reading between 6:00 a.m. and 11:59 a.m. (β = −0.78, SE = 0.22, and p < 0.001). In recreational reading, however, reading between noon and 6:00 p.m. was associated with lower log odds of displacement relative to the morning period (β = −0.41, SE = 0.21, and p = 0.050).

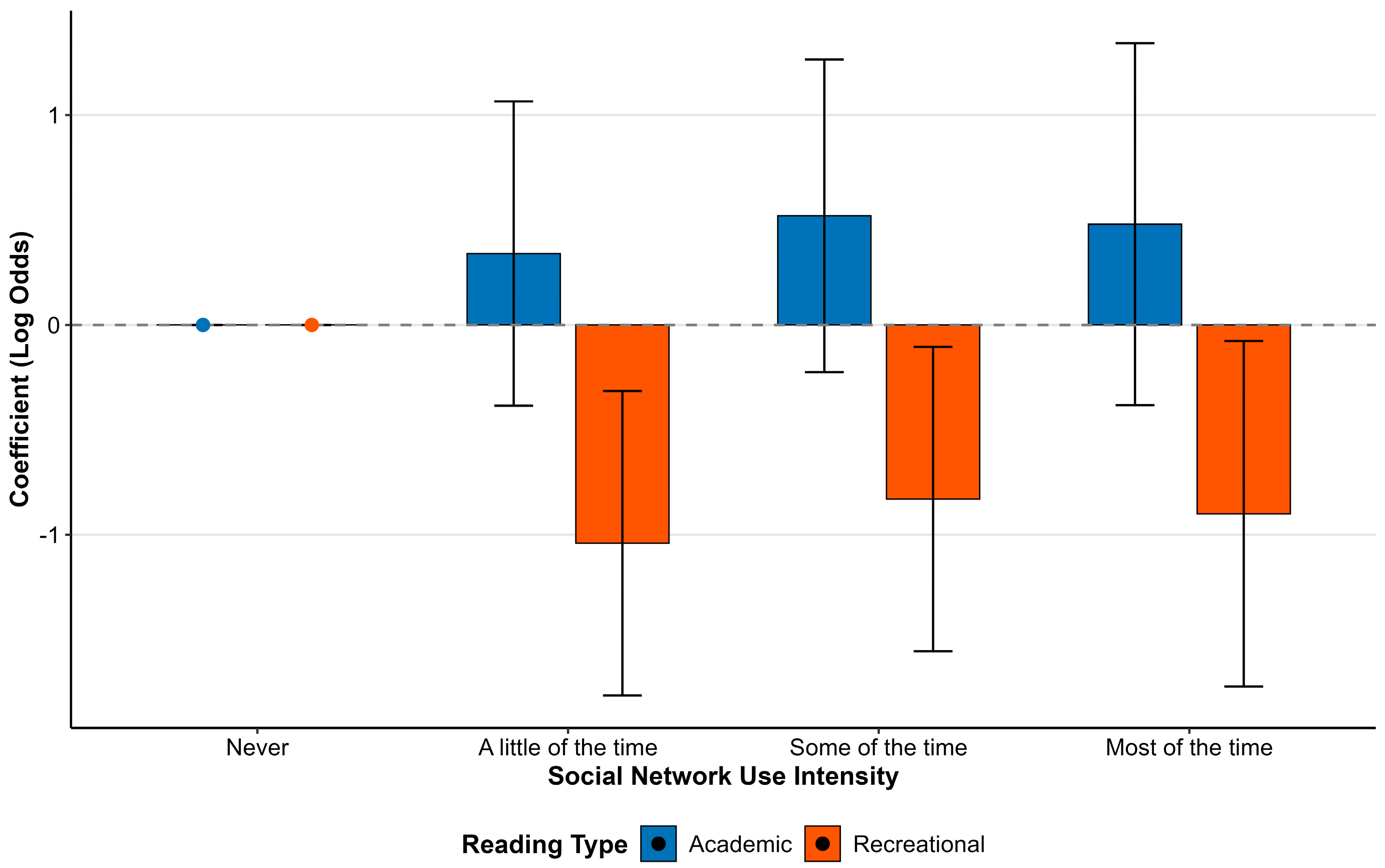

The effect of watching TV while reading was consistent across both reading types, with “most of the time” TV watchers showing significantly higher odds of displacement in both academic (OR = 2.65; 95% CI [1.16, 6.06]) and recreational (OR = 2.61; 95% CI [1.18, 5.79]) contexts. However, the most striking difference between the models was observed for social media use. For academic reading, using social networks, whether “a little of the time” (β = 0.34, SE = 0.37, and p = 0.362), “some of the time” (β = 0.52, SE = 0.38, and p = 0.166), or “most of the time” (β = 0.48, SE = 0.44, and p = 0.281), did not significantly alter the log odds of higher displacement compared with nonuse. In contrast, for recreational reading, moderate-to-high social network usage significantly reduced the log odds of reporting higher displacement (“a little of the time”: OR = 0.36; 95% CI [017, 0.73]; “some of the time”: OR = 0.44; 95% CI [0.21, 0.89]; “most of the time”: OR = 0.41; 95% CI [0.18, 0.92]).

Figure 2 underscores these distinctions, with the coefficients for academic reading (blue) clustering near zero and those for recreational reading (red) displaying larger negative values. The plot also indicates that shifts from “no displacement” to “some displacement” were more common than transitions to “a lot of displacement”, especially in academic contexts.

A test for the interaction effects revealed a significant interaction between experience and school type for academic reading (χ2(2) = 7.65; p = 0.022), indicating that the protective effect of experience was more pronounced in urban/suburban schools than in rural schools. No significant interaction was found between school type and TV watching for recreational reading (χ2(3) = 2.36; p = 0.501).

In summary, the findings reveal that the factors influencing time displacement differed between academic and recreational reading. While teaching experience, school type, and reading timing significantly affected displacement in both contexts, media multitasking behaviors exhibited context-dependent effects. Notably, watching TV consistently increased the likelihood of displacement across reading types, whereas the effects of social network use and video game playing were more nuanced. The observation that more-experienced teachers reported reduced displacement suggests they may have developed effective strategies to mitigate the disruptive effects of media multitasking. These results underscore the importance of considering contextual differences when assessing the impact of media multitasking on reading activities.

6. Discussion

This time-diary survey investigated the impact of media multitasking on the reading habits and practices of Moroccan EFL teachers. Our findings indicate that media multitasking, particularly Internet use and TV viewing, significantly displaces time spent on both academic and recreational reading, extending previous research on college students and adults (

Delello et al., 2016;

Griswold & Wright, 2004;

Mokhtari et al., 2009) to this specific population. Below, we discuss key findings in relation to each research question and their theoretical and practical implications.

Addressing our first research question, we found that teaching experience, school type, time of day, and specific multitasking activities significantly predicted displacement from academic reading. More-experienced teachers reported less displacement, suggesting the development of cognitive strategies to manage digital distractions. This finding aligns with the cognitive load theory perspective (

Sweller et al., 2019), which proposes that expertise in a domain frees up cognitive resources that can be allocated to managing potential distractions. This interpretation is consistent with

Stone’s (

2009) distinction between continuous partial attention and intentional task-switching. Our results suggest that experienced teachers might develop metacognitive awareness and routines that reduce interference from competing stimuli—not necessarily by becoming better at simultaneous multitasking, but potentially by developing more effective intentional task-switching strategies that allow them to engage with media briefly before returning to focused reading, rather than remaining in a state of continuous partial attention. This interpretation is also consistent with research by

Carrier et al. (

2015), emphasizing that task familiarity modulates the effects of competing activities on performance.

School type (rural vs. urban/suburban) emerged as a consistent predictor across both academic and recreational reading, with urban/suburban teachers reporting greater displacement than their rural counterparts. This finding suggests that environmental factors in rural areas may be associated with more focused reading practices (

Chiu & Chow, 2010). Several possible mechanisms might explain this pattern. Rural settings may provide fewer distractions or a different pace of life that correlates with more uninterrupted time dedicated to reading. Alternatively, urban/suburban environments, with their higher levels of digital connectivity and media availability (

Hargittai & Hinnant, 2008), might contribute to greater multitasking behaviors and, hence, more significant displacement. Future research should explore specific factors within these settings that contribute to this variation, such as the availability of media, cultural attitudes toward technology, and the physical environment’s role in facilitating or hindering focused reading.

Our analysis revealed that evening reading (6:00 p.m.–11:59 p.m.) was associated with less displacement from academic reading compared with morning sessions. This counterintuitive finding seems to challenge assumptions that evening hours, traditionally associated with leisure, would witness more digital interference. One possible explanation involves the theory of attentional control (

Eysenck et al., 2007), which distinguishes between goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention systems. Teachers may establish stronger goal-directed control during evening reading sessions precisely because they anticipate potential distractions, resulting in more focused reading practices.

The data showed a significant relationship between watching TV while reading for academic purposes and increased displacement, with teachers who reported watching TV “most of the time” while reading having 2.65 times higher odds of displacement compared with those who “never” watched TV. This strong association underscores the potentially competitive nature of these activities (

Levine et al., 2007). This substantial relationship also aligns with task-switching research demonstrating that activities requiring similar cognitive resources (in this case, visual processing and verbal comprehension) tend to show stronger interference patterns than dissimilar tasks (

Salvucci & Taatgen, 2011). The relatively continuous attention demands of television likely compete with the sustained attention required for academic reading.

For our second research question examining factors influencing displacement from recreational reading, similar patterns emerged regarding school type and television viewing. However, we observed notable differences in the effects of reading duration and social media use. Teachers who engaged in longer recreational reading sessions (30–89 min) reported significantly less displacement than those reading for shorter periods (<30 min). This highlight suggests that extended reading sessions may foster a state of “flow” or deep engagement (

Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) that renders readers less susceptible to digital distractions.

The most surprising finding concerned social network use during recreational reading. Contrary to our expectations, teachers who used social networks while reading for pleasure reported significantly less displacement than those who never used social media. This counterintuitive result suggests a more nuanced relationship between social media and recreational reading than simple displacement. While our data do not provide direct insights into the specific ways teachers navigate between these activities, the differential patterns observed between recreational and academic reading contexts suggest that the nature of the primary activity (reading) may influence how secondary activities (social media use) are integrated or experienced. This finding aligns with the recent work by

Mangen and van der Weel (

2016) proposing an integrative framework that considers how digital technologies might complement rather than simply displace traditional reading practices.

An alternative explanation involves the distinction between continuous partial attention and task-switching patterns, as conceptualized by

Stone (

2009). Continuous partial attention involves constantly monitoring multiple information streams without fully focusing on any single activity, while intentional task switching involves suspending one activity to engage in another before returning (

Stone, 2009). Academic reading typically requires sustained attention to complex information, making it potentially more vulnerable to disruption from the continuous partial attention pattern, while recreational reading might be more compatible with deliberate task-switching between reading and social media use. The less-structured nature of recreational reading may allow for natural breaking points, where switching to social media temporarily does not significantly disrupt the overall reading experience. However, we acknowledge that investigating these specific mechanisms would require different methodological approaches, such as qualitative interviews or observational studies that could capture the temporal patterns and subjective experiences of reading with media multitasking.

Our third research question examined differences in displacement patterns between academic and recreational reading. The most notable finding was the differential impact of social network use across reading contexts. While social media use had no significant effect on displacement from academic reading, it was associated with reduced displacement during recreational reading. This context-dependent effect supports the task-switching theory (

Monsell, 2003), which proposes that switch costs, the cognitive penalties associated with shifting attention between tasks, vary based on the task characteristics and individual expertise.

Academic reading typically requires deep processing, sustained attention, and complex cognitive operations (

Wolf & Barzillai, 2009), making it particularly vulnerable to disruption from attention-shifting activities. In contrast, recreational reading often involves more flexible attention patterns and is intrinsically motivated, potentially making it more resilient to certain forms of interruption. This interpretation aligns with the research by

Junco and Cotten (

2012), demonstrating that social media use during academic activities has more detrimental effects than during leisure activities.

The differential effects of school context across reading types, with urban/suburban teachers reporting significantly higher displacement for recreational reading (OR = 2.23) compared with academic reading (OR = 1.42), suggest that environmental factors may have stronger influences on discretionary versus professional reading behaviors. Urban environments may offer more competing leisure activities and normalized digital multitasking behaviors that specifically impact recreational reading. This finding extends previous work by

Hargittai and Hinnant (

2008) on digital literacy divides between urban and rural contexts.

Our findings also reveal a significant interaction between experience and school type for academic reading, with the protective effect of experience being more pronounced in urban/suburban schools than rural schools. This finding suggests that experienced teachers in more digitally saturated environments may have developed strategies to maintain focused academic reading habits. As

K. K. Loh and Kanai (

2016) noted, expertise may serve as a buffer against environmental factors that would otherwise disrupt cognitive performance.

This study contributes to the theoretical understanding of media multitasking in several ways. First, our findings support a contextual rather than universal understanding of digital displacement effects. The differential impacts of social media use on academic versus recreational reading suggest that we should move beyond simple displacement hypotheses (

Nie & Erbring, 2002) toward more nuanced frameworks that consider activity characteristics, environmental contexts, and individual factors simultaneously.

Second, our results align with the emerging theoretical perspective that digital media effects are mediated by intentionality and agency (

Mangen & van der Weel, 2016). The finding that more-experienced teachers report less displacement suggests that individuals can develop metacognitive strategies to manage digital distractions effectively. Rather than positioning media users as passive recipients of technological determinism, our study highlights the potential for agency and adaptation.

Third, the consistent finding that television viewing increases displacement across both reading contexts provides empirical support for the cognitive load perspective (

Carrier et al., 2015), which proposes that tasks competing for similar cognitive resources create greater interference. Television requires sustained visual attention and verbal processing, resources also central to reading, potentially explaining its disruptive effect.

Finally, the interaction between experience and school context contributes to theoretical models of expertise development in digital environments. This finding suggests that expertise may involve not only domain-specific knowledge but also contextually adapted strategies for managing attention in increasingly media-saturated environments.

Our findings have several practical implications for teacher education and professional development. First, the protective effect of teaching experience in managing digital distractions suggests that novice teachers could benefit from explicit instruction in metacognitive strategies to reduce distractions (

Bentahar, 2022). Teacher education programs should incorporate media literacy components that address not only critical evaluation of digital content but also practical approaches to managing attention in media-rich environments.

Second, the differential vulnerability of academic versus recreational reading to certain forms of digital interference highlights the need for context-specific strategies. Professional development initiatives should acknowledge that different reading purposes require different approaches to managing digital distractions, rather than advocating for one-size-fits-all solutions.

Third, the consistent finding that television viewing disrupts both academic and recreational reading suggests that teachers and, by extension, their students, may benefit from creating physical and temporal boundaries around reading activities that specifically exclude television. This aligns with recommendations from attention researchers who suggest that environmental design can support cognitive control (

Salvucci & Taatgen, 2011).

Finally, the rural–urban differences observed in our study indicate that educational policies related to technology use may need regional adaptation. Rural teachers appear to experience less digital displacement, suggesting that factors in these environments may be protective. Identifying and potentially transferring protective elements to urban educational contexts could help mitigate digital disruption among urban teachers.

For individual teachers seeking to improve their reading habits, our findings suggest several practical strategies: scheduling longer reading sessions to establish flow states resistant to interruptions; prioritizing evening hours for academic reading when possible; creating environments that minimize visual distractions (particularly television); and developing intentional approaches to social media use that complement rather than compete with reading activities.

7. Limitations

The current study had limitations that should be acknowledged and addressed in future research. First, the reliance on self-reported data from a single time-diary survey may have introduced recall bias or social desirability bias, despite the advantages of this method over traditional retrospective surveys (

Kaufman & Lindquist, 2019). Future research could employ multiple data collection methods, such as observational studies, experience sampling, or digital-tracking applications, to triangulate findings and reduce potential biases.

Second, the cross-sectional design of this study precluded causal inferences about the relationship between media multitasking and reading displacement. Longitudinal or experimental studies tracking teachers’ reading and media habits over time would provide stronger evidence for causal relationships and could identify developmental trajectories in how teachers learn to manage digital distractions throughout their careers.

Third, while our focus on Moroccan EFL teachers provides valuable insights into an understudied population, it also limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations or contexts, as media use patterns and reading habits may vary due to cultural, technological, or institutional factors. Morocco’s specific educational infrastructure, digital access patterns, and cultural attitudes toward technology may shape media multitasking behaviors in ways that differ from other regions. Replication studies with diverse samples would help establish the external validity of the current findings.

Fourth, our measures focused primarily on self-reported time displacement rather than cognitive outcomes, such as comprehension, retention, or critical analysis. Future studies should incorporate measures of reading quality alongside quantity to provide a more comprehensive picture of how media multitasking affects teachers’ reading effectiveness, not just duration.

Fifth, our analysis did not fully examine the potential relationship between media multitasking, reading displacement, and teacher well-being. Given the high rates of occupational stress and burnout in the teaching profession, future research should examine how digital displacement of reading may relate to work–life balance, stress management, and professional satisfaction. Such research might explore whether certain patterns of media multitasking could potentially represent adaptive or maladaptive strategies for managing occupational demands, though establishing such relationships would require different methodological approaches than those employed in this study.

Finally, while our study identified experience-level differences in managing digital distractions, we did not directly investigate the specific strategies that experienced teachers employ. Qualitative studies using interviews or think-aloud protocols could identify the metacognitive approaches and environmental modifications that successful teachers use to maintain focused reading habits despite digital temptations. These insights could inform more targeted interventions for novice teachers.

Future research should also explore how the patterns identified in this study manifest in classroom teaching practices. Do teachers who struggle with media multitasking in their personal reading habits similarly struggle to model focused reading for their students? Do they implement different classroom policies regarding technology use based on their own experiences with digital displacement? Answering these questions could help bridge the gap between teachers’ personal media habits and their instructional effectiveness.

8. Conclusions

This study investigated the media multitasking habits and reading practices of Moroccan EFL teachers, focusing on the potential displacement effects of watching TV and Internet use on time spent reading for academic and recreational purposes. Our findings indicate that a significant proportion of teachers engage in media multitasking while reading, which is associated with reduced time spent on both academic and recreational reading. However, these effects are not uniform across contexts or teacher characteristics, with important differences emerging between academic and recreational reading, novice versus experienced teachers, and urban versus rural school settings.

This study makes several key contributions to the literature on media multitasking and reading practices. First, it highlights the context-dependent nature of digital displacement effects, with different patterns emerging for academic versus recreational reading. Second, it identifies teaching experience as a potential protective factor against digital displacement, suggesting the development of metacognitive strategies with professional maturity. Third, it reveals environmental differences between urban and rural educational settings that influence digital reading practices. Finally, it distinguishes between different forms of media multitasking, with television viewing emerging as particularly disruptive across contexts.

Based on our findings and acknowledging the correlational nature of our study, we suggest several considerations for teachers interested in understanding factors associated with reading displacement:

Our data showed a consistent association between television viewing and reported displacement across both reading contexts—academic and recreational. Teachers might consider reflecting on how visual media environments relate to their reading experiences.

The observed association between longer reading sessions (30 min or more) and lower reported displacement suggests potential value in examining how different reading durations relate to perceptions of distractions.

Given our finding that evening hours were associated with less reported displacement for academic reading, teachers might benefit from exploring how the timing of different reading activities aligns with their personal patterns of focus and distraction.

The differential relationships we observed between social media use and reading displacement across academic and recreational contexts suggest that examining the role of social media in different reading activities may be worthwhile.

Our findings show distinct patterns between academic and recreational reading contexts, indicating that reflection on how different types of reading activities might benefit from different approaches to media engagement could be valuable.

The association between teaching experience and lower reported displacement suggests that conversations among teachers with varying levels of experience about their approaches to reading in media-rich environments might yield useful insights.

For teacher education programs, our findings highlight the potential value of discussions about the relationships between media environments and reading practices as part of broader media literacy initiatives.

Teacher education programs and professional development initiatives could incorporate discussions about media literacy that address not only content evaluation but also patterns of media engagement. By helping teachers become more aware of the relationships between media habits and reading experiences, we may support their professional development and the literacy models they provide for their students.

Future research is needed to establish causal relationships and test interventions based on these observed associations. Such studies could determine whether modifying specific factors (e.g., reading duration, environmental conditions, and media access during reading) directly influences reading displacement outcomes.