Abstract

This paper investigates the extent to which the teacher factors of the dynamic model of educational effectiveness are related to each other forming stages of effective teaching. It also investigates whether teachers situated at higher stages are more effective than those situated at lower stages in terms of promoting student learning outcomes. All grade 4 teachers (n = 31) of eight schools and their students (n = 350) in the urban capital of Male’ city in the Maldives participated in this study. Teacher factors were measured through a student questionnaire. External tests were used to measure student achievement in English language at the beginning and end of the 2019–2020 school year. Teacher factors were grouped into six stages of teaching. Multilevel regression analysis revealed that students of teachers situated at higher stages have better learning outcomes than students of teachers situated at lower stages. Implications of findings for research, policy and practice are drawn.

1. Introduction

Educational effectiveness research (EER) reveals that teacher behaviour in the classroom plays a more significant role in promoting student learning outcomes than factors situated at the school or the educational system level (e.g., Scheerens, 2013; Kyriakides et al., 2021; Muijs et al., 2014). In this context, several theoretical frameworks and models of effective teaching have been developed (e.g., Klieme et al., 2009; Kyriakides et al., 2024a), and several studies have been conducted to test the validity of these models (Praetorius et al., 2018). Yet, research on effective teaching has not been consistently applied to improve teachers’ professional development, and a gap between EER and research on teacher professional development can be identified (Creemers & Kyriakides, 2010). In this context, Creemers and Kyriakides (2008) proposed the Dynamic Model of Educational Effectiveness (DMEE), which aims to establish links between EER and research on teacher and school improvement (Kyriakides et al., 2021). This model does not only refer to factors operating at different levels (i.e., student, teacher, school and system) but also assumes that factors operating at the same level are related to each other. The study reported here was conducted in the Maldives and aimed to test this assumption by searching for the extent to which teacher factors of DMEE are related to each other.

Contextual Relevance: The Maldivian Education System

The Maldives presents a unique educational context for this study. In recent years, the country has implemented significant reforms to increase access to education and improve teacher quality (UNESCO, 2017). However, challenges in teacher training and professional development persist, including inconsistencies in teacher training programs and limited resources (Di Biase & Maniku, 2020). Furthermore, the Maldives’ centralized education system and geographical dispersion of schools across islands present additional challenges for promoting effective teaching practices (World Bank, 2021). These unique contextual factors highlight the need for adapting international frameworks to local realities and highlight the importance of testing the applicability of educational effectiveness models such as the DMEE in this setting. Studies testing the assumption of the DMEE that teacher factors are related to each other have been conducted mainly in Europe. This study aims to test this assumption of the DMEE further and examines whether stages of effective teaching can be identified within a different context by collecting data from primary school teachers in the Maldives. This setting provides a unique context, as the Maldivian education system, including its teacher training programs, may present distinct challenges and opportunities. In addition, identifying stages of effective teaching may help policymakers and teacher trainers to develop comprehensive teacher improvement strategies.

2. Identifying Stages of Effective Teaching

The concept of “stages” of effective teaching refers to the progressive levels or phases of teaching practices that contribute to improved student learning outcomes. A review of the literature on these stages, both within and beyond teaching, revealed that while the identification of stages has contributed significantly to our understanding of teacher effectiveness (Creemers et al., 2013b), there are still gaps in how these stages are applied and validated across different educational systems and cultures (Scheerens, 2016). These gaps highlight the need for research that connects theoretical models to practical improvements in teaching. This study aimed to address these weaknesses by providing empirical evidence on the identification of stages of effective teaching by making use of the DMEE in the Maldivian context.

Challenges with Existing Frameworks

An important constraint observed in existing frameworks and models of teacher effectiveness is that these approaches (e.g., Carter et al., 2024; Kyriakides et al., 2015; Sims et al., 2023) have not significantly contributed to the improvement of teaching practices (Scheerens, 2013). This limitation is also highlighted in the literature, where it is noted that many of these frameworks are rarely used to improve the quality of teaching and learning in real classrooms (Kyriakides et al., 2018; Sancar et al., 2021). Educational effectiveness research (EER) supports this critique, indicating that while teacher behaviour in the classroom plays a critical role in improving student achievement, yet integrating findings into actionable classroom strategies remains a challenge (Chapman et al., 2016).

Over the last five decades, the demand for improving the quality of teaching is high on the agenda of researchers and educators (Desimone, 2009; Sims et al., 2023). For instance, in the late 1970s and beginning 1980s, a growing body of literature on teacher career stages emerged (e.g., Burden, 1979; F. F. Fuller, 1969; F. Fuller & Bown, 1975; Newman, 1978; Peterson et al., 1978) that attempted to study quality teaching characteristics. The focus was mainly on studying teachers’ behaviours in relation to attitudes and teacher concerns during the different stages of a teacher’s career. In addition, most studies were concerned with preservice teachers, studying general characteristics that were observed in teachers in the beginning and through the first few years of a teacher’s teaching career (Trotter, 1986). These studies assumed that every teacher began in the survival stage or low developmental stage (e.g., F. F. Fuller, 1969) where the teacher aims to survive the system, and ends in the final stage of the highly developmental stage or maturity stage where the teacher peaks at quality teaching. The main issue with this research approach is that the assumption is made for teachers to consecutively move from one stage to another based only on teachers’ years of training and experience and not necessarily advanced teaching methods that they use in the classroom to maximize learning gains of students (Dimosthenous et al., 2020; Kyriakides et al., 2017).

This gap highlights the need for models that account for the actual teaching practices and their impact on student learning outcomes, rather than relying solely on chronological career stages. Some of these studies also have differentiated between early career and seasoned teachers by considering the depth and complexity of cognitive frameworks teachers possess during their career (e.g., Berliner, 1994; Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1980; Feiman-Nemser & Remillard, 1996). For example, these stage models assume that around the fifth year of teachers’ career, the teacher can successfully move to the mature stage with all the characteristics that makes an effective teacher (Burden, 1979). However, this assumption lacks empirical evidence (Kyriakides et al., 2021). We also observed that these studies fail to explain explicitly the specific characteristics that teachers possess in each stage in relation to actual classroom teaching. Although the Dreyfus model (Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1980) advances in understanding of skill development when compared with other stage models, it still lacks clarity about what constitutes skill in teaching and what characterizes and distinguishes the skilful performance (Dall’Alba & Sandberg, 2006). The set of effective characteristics that teachers need to possess for each stage is still not prescribed explicitly in any of the stage models. It can also be argued that the teacher attributes are usually identified and described in a decontextualized manner, separate from the practice to which they refer to. Burden (1982) emphasized the need for additional studies and the need to further clarify the developmental characteristics of these stages through a model-based integrated approach.

The stage models (e.g., Berliner, 1994; Ericsson & Smith, 1991) also work under the assumption that teachers must pass through several periods of development to allow for sufficient time and training to meet the expectations of each stage. This commonly held view equates quantity of time in the classroom with improvement of quality of teaching instruction. Hence, it has been observed that there is a common consensus of belief that sequential hierarchical development of teachers is tied to only experience (Sancar et al., 2021). This view fails to address how quality teaching practices can be fostered independently of the time spent in the classroom. It is stressed here that several studies (e.g., Sandberg, 1994; Dall’Alba & Sandberg, 2006) have revealed that a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of practices are infrequent in professions. The limitations of these existing frameworks highlight the need for a more balanced approach to understanding and improving teaching effectiveness (Mockler, 2022). Therefore, this study aimed to examine the extent to which the teacher factors of the DMEE may help us identify stages of effective teaching that can be used for teacher improvement purposes.

3. Using the Dynamic Model of Educational Effectiveness to Identify Stages of Effective Teaching

The DMEE was designed to establish stronger links between EER and teacher improvement (Creemers et al., 2013a). Specifically, the DMEE does not only refer to factors operating at four levels (i.e., student, teacher, school, and system) associated with student learning outcomes but proposes a framework to measure the functioning of each factor. Five measurement dimensions (i.e., frequency, stage, focus, quality, and differentiation) are used to measure not only the quantitative but also qualitative characteristics of each factor. Frequency is a quantitative measure that assesses how often a particular teaching behaviour occurs. The other four dimensions examine qualitative aspects of how effectively a factor functions. For instance, focus refers to the balance teachers maintain between different tasks during a lesson, an approach that supports the idea that interaction and adaptability are essential in any organizational setting, including classrooms (Scheerens, 2013). The integration of both quantitative and qualitative characteristics through these dimensions allows for a more nuanced evaluation of effective teaching practices. This approach enables the development of more comprehensive strategies for improving teaching (Kyriakides et al., 2021).

In the context of the classroom, the DMEE focuses on observable behaviours of teachers, rather than the factors that may explain these behaviours (such as teacher beliefs and attitudes). More specifically, it focusses on the following eight teacher factors: orientation, structuring, questioning, modelling, application, time management, the teacher’s role in creating a conducive learning environment, and assessment. These factors, which are briefly described in Table 1, are based on findings of many studies demonstrating their relations with student learning outcomes (e.g., Brophy & Good, 1986; Muijs et al., 2014; Scheerens, 2013; Sims et al., 2023). Table 1 also reveals that the DMEE adopts an integrated approach to effective teaching, drawing from various theories of learning and approaches to teaching (Elboj & Niemelä, 2010; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). For instance, factors such as structuring and application align with the direct teaching approach, which emphasizes clear instructions and structured learning activities (e.g., Rosenshine, 2012). In contrast, factors like modelling and orientation are rooted in constructivist approaches, where students actively construct knowledge through guided exploration and contextual understanding (Schoenfeld, 1998; R. Fox, 2001). Moreover, the importance of collaboration is incorporated under the broader factor of the teacher’s contribution to establishing a positive classroom learning environment. Specifically, this factor is concerned with the encouragement of not only teacher–student but also student–student interactions. This collaborative aspect plays a crucial role in creating an interactive and supportive classroom dynamic, further enhancing the learning experience (Slavin & Cooper, 1999; Sun et al., 2022).

Table 1.

The main elements of each teacher factor included in the Dynamic Model of Educational Effectiveness (DMEE) (adopted from Kyriakides et al., 2021).

Another critical characteristic of the DMEE is its assumption that teaching factors operating at the same level are interrelated. This implies that improvement strategies and action plans should address these factors collectively, rather than in isolation, to maximize their effectiveness. While more than 20 studies have investigated the impact of teacher factors on promoting student learning outcomes, only five studies have explicitly tested this assumption (Kyriakides et al., 2021). These five studies were able to highlight the interconnectedness of specific teacher factors and dimensions and stages of effective teaching have been proposed (e.g., Antoniou & Kyriakides, 2013; Azkiyah et al., 2014). These studies, however, have taken place in European countries and in Canada, which emphasizes the need for research in different settings, such as the Maldives, to further validate the model’s applicability in searching for stages of effective teaching that can be used for improvement purposes.

4. Research Aims

The primary goal of this research was to search for relationships among the eight teacher factors of the DMEE and their measurement dimensions in order to identify specific groupings of factors that may stand as stages of effective teaching. We also explored the extent to which primary teachers in Maldives situated at higher stages are more effective than those situated at lower stages in terms of promoting student learning outcomes in teaching English as a second language. Providing answers to these two main research questions, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how effective teaching practices can be optimized in diverse educational environments. Thus, we also searched for similarities and differences of the findings of this study with the stages that have emerged in other countries (mainly Europe).

5. Methods

5.1. Participants

This study was conducted in the urban capital city of Male’, Maldives, which houses 18 primary schools (World Bank, 2021). Male’ was selected for data collection due to its accessibility and because it is the most populous city in the country, with the highest concentration of primary schools on a single island. A stage sampling procedure was used. At the first stage, the following four districts out of the six districts of this area were randomly selected: Henveiru, Galolhu, Maafannu, and Macchangoalhi. At the second stage, all primary schools of these four districts were approached (n = 14) for participation, and eight schools agreed to participate. All grade 4 classes (n = 31) of participating schools were selected and parental consent was received from a total of 380 students. The student sample included 177 male and 173 female students. Grade 4 students were chosen since meta-analyses of educational effectiveness research (e.g., Kyriakides et al., 2013b; Scheerens, 2016) revealed that teachers have a bigger effect on student learning outcomes to younger students (e.g., grades 1–4) and a smaller effect on older students (e.g., secondary students). Moreover, studies investigating the impact of teacher factors of the DMEE on student learning outcomes reveal that primary students in grade 4 are capable of providing valid data on their teachers’ behaviour in the classroom in relation to the teacher factors of the model (Panayiotou et al., 2014). These results can be attributed to the fact that the eight teacher factors refer to observable behaviour and to teaching actions that relatively young students are capable of identifying and offering their opinions about whether and to what degree they take place. The questionnaire does not refer to inferences about the quality of their teacher in an abstract way; instead, students are asked to report on whether or not concrete actions take place in their classroom (Kyriakides et al., 2021). It is also important to note that a chi-square test indicated no statistically significant difference between the sample and the population in terms of gender (X2 = 1.06, df = 1, p = 0.30). Missing student assessment data primarily resulted from student absences at either the pre-test or post-test, while self-selection bias was unlikely due to the low-stakes nature of the assessments. Full data were available for 350 of the 380 students in the final sample (92.1%), eliminating the need for imputation.

5.2. Variables and Measurement Scales

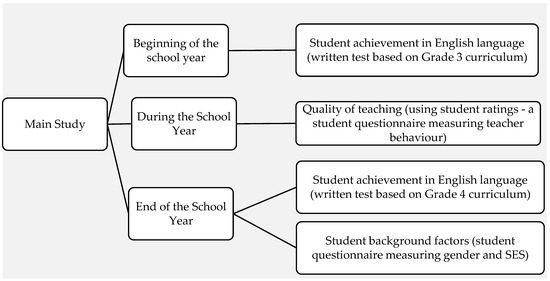

This section provides a detailed description of the variables and measurement scales used in this study. Figure 1 provides a visual summary of the phases undertaken during the main study, as well as the measurement variables and scales. One can see that three measurement periods were used to collect data: the beginning of the school year (i.e., February), during the second terms of the school year (i.e., from September up to October), and the end of the school year (i.e., November). At the beginning and at the end of the school year, data on student achievement were collected, whereas quality of teaching was measured through a student questionnaire which was administered from February up to June. More information about each variable of the study is provided below.

Figure 1.

Phases of the main study and measurement variables.

5.2.1. Student Achievement in English Language

Student achievement in the English language, specifically in reading comprehension and writing skills, was measured both at the start (i.e., beginning of Term 1) and end (i.e., end of Term 2) of the 2019–2020 school year. At the time of undertaking the research, there were no standardized English tests developed in the Maldives, and international tests could not be used since these tests were not in line with the country-specific curriculum of Maldives. Thus, the tests were designed to align with the expected learning outcomes of the National Curriculum Framework of the Maldives (NIE, 2011). Specifically, in collaboration with expert teachers and ministry officials, we initially developed a specification table covering the basic skills in English language that were expected to be taught to students in grades 3 and 4. Based on this table, two written tests were developed which measure the following language domains: reading (comprehension) and writing (content, grammar, spelling, sentence structuring). However, the tests assessed these skills in an integrated manner since a single item/task assessed multiple domains. Specifically, the tests were designed to measure reading strategies; comprehension; reflection on reading; and the ability to write clear, personal, and imaginative content from the curriculum. At least two different test tasks were concerned with each objective of the curriculum of each grade. Item formats included reading a passage followed by multiple-choice questions to assess comprehension and writing two essays to evaluate writing skills. The test based on the grade 3 curriculum was used to measure students’ prior knowledge and skills, whereas the test based on the grade 4 curriculum was used to measure student achievement at the end of the school year. Scoring rubrics allowed to categorize performance into three proficiency levels for every task, which allowed for the collection of ordinal data reflecting how well each student had attained the English language objectives.

Data analysis was conducted using the Extended Logistic Model of Rasch (Andrich, 1988), which showed that each scale had satisfactory psychometric properties. The separation indices for both cases (students) and items exceeded 0.86, indicating good reliability (Wright, 1985). The mean infit and outfit mean squares were close to one, with infit and outfit t-scores near zero, suggesting a good model fit. Item infit values ranged from 0.88 to 1.11, confirming the data’s alignment with the Rasch model (Keeves & Alagumalai, 1999). As a result, two achievement scores for each student in English language were calculated based on the Rasch person estimate for each scale.

5.2.2. Quality of Teaching

Teaching quality was evaluated by means of student ratings, a widely recognized method for evaluating teacher performance (Fresko & Nasser, 2001; Kyriakides et al., 2014). It is acknowledged here that data could be also collected by conducting external observations using the instruments which have been developed and validated for measuring quality of teaching in relation to the factors of the DMEE (for information on the instruments, see Creemers & Kyriakides, 2012). However, several teachers in the Maldives did not feel comfortable having external observers in their classrooms. Thus, using this method of data collection may have caused difficulties in reaching a sufficient number of teachers to conduct this study. It should also be mentioned that more than 8 studies testing the validity of the DMEE at teacher level did not make use of the external observation instruments but were in a position to detect effects of teacher factors of the DMEE on student learning outcomes (see Kyriakides et al., 2021). Thus, students were asked to rate their teachers on various aspects of teaching behaviour using a five-point Likert scale. For the purposes of this study, the student questionnaire measuring teacher behaviour in regard to the factors of the DMEE was used (see Creemers & Kyriakides, 2012). After a double translation procedure and some minor adaptations, a version of the questionnaire used in the Maldives was developed (see Musthafa & Kyriakides, 2023). It is important to note that students were asked to rate on a Likert scale their teacher’s behaviour. For instance, students were asked to indicate whether their teacher effectively structured lessons by explaining how new lessons relate to previous ones.

Initially, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that data emerged from each questionnaire item are generalisable at the class/teacher level. Then, the construct validity of the questionnaire was tested by considering the data that emerged from all items and running separate multilevel confirmatory factor analyses per teacher factor. The results of multilevel CFA revealed that the five first-order factor model fitted to the data, implying that all factors can be measured by considering the five dimensions of the DMEE. In the case of management of time, all items were found to belong to a single factor. This result is in line with the way teacher factors are defined by the DMEE, especially since only the frequency dimension was employed to evaluate the management of time factor. In regard to the classroom as a learning environment factor, three different aspects of this overarching factor were identified (i.e., encouraging (a) teacher–student interactions, (b) student–student interactions, and (c) managing student misbehaviour).

5.2.3. Student Background Factors

Gender and students’ socioeconomic status (SES) were measured. Five SES variables were available: father’s and mother’s education level, the social status of the father’s job, the social status of the mother’s job, and the main elements of the home learning environment. Data from the school records measuring these SES variables were analysed by using the Extended Logistic Model of Rasch (Andrich, 1988). Analysis of the data revealed that the scale had satisfactory psychometric properties. Thus, a score for the SES of each student was calculated using the relevant Rasch person estimate.

6. Data Analysis and Results

6.1. Searching for Stages of Effective Teaching

6.1.1. Using the Rasch Model to Specify the Hierarchy of Teaching Skills’ Difficulties

Having established the construct validity of the framework used to measure the dimensions of the factors of the DMEE, it was decided to use the Rasch model to identify the extent to which the five dimensions of teacher factors of the DMEE (i.e., the 41 trait scores emerged from the CFA analyses) could be reducible to a common unidimensional scale. The Rasch model can find out whether the tasks (i.e., teaching skills) can be ordered according to the degree of their difficulty. At the same time, the people who carry out these tasks (i.e., teachers) can be ordered according to their performance in the construct under investigation. This study identified teachers’ positions on the teaching skill scale, distinguishing those with adequate performance (scoring higher) from those with insufficient performance (scoring lower). It also enabled comparisons of the difficulty of each teaching skill. Also, a teacher’s position on the continuum predicts the likelihood of their teaching competence being above or below this point (Bond & Fox, 2001). The Rasch model was applied to all 41 teaching skill measures using the Quest program (Adams & Khoo, 1996). After dropping four factor scores concerned with three dimensions of dealing with misbehaviour (i.e., focus, stage and differentiation) and with the focus dimension of student–student interactions, the remaining 37 items of the DMEE were found to fit the model well. Specifically, all 37 measures of teaching skills had item infit within the range from 0.86 up to 1.12, and item outfit within the range from 0.83 up to 1.13. Moreover, these skills were well targeted against the teachers’ measures since teachers’ scores ranged from −2.03 to 2.11 logits and the difficulties of the 41 teaching skills ranged from −1.89 to 1.99 logits. Furthermore, the indices of persons and of teaching skills separation were found to be higher than 0.89, indicating that the separability of the scale was satisfactory (Bond & Fox, 2001).

6.1.2. Using the Saltus Model to Identify Stages of Effective Teaching

The application of Marcoulides and Drezner’s (1999) cluster analysis to segment the 37 teaching skills based on their difficulties that emerged from the Rasch model showed that they could be optimally clustered into six groups (i.e., stages of teaching), shown in Table 2. Specifically, the cumulative D for the six-cluster solution was 71%, whereas the seventh gap added only 3%. Then, the Saltus model was applied, and we assumed that the 37 teaching skills could be structured into the six groups of the cluster analysis. The Saltus solution was found to have better fit to the actual data than the Rasch model and offered a statistically significant improvement over the Rasch model, which was equal to 1351 chi-square units at the cost of 42 additional parameters (i.e., 25 t values, six means, six standard deviations, and five independent proportions). Table 2 presents the difficulty parameters of the 37 teaching aspects for teachers in the easiest stage of effective teaching (i.e., Stage 1 shown in Column 3) and the implied within stage difficulty (i.e., Columns 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8). The Saltus parameter estimates (i.e., t values) are shown in the lower part of Table 2. Each stage is described below by considering the teaching skills found to be situated in each level.

Table 2.

Rasch and Saltus parameter estimates for factor scores measuring the classroom level factors of the dynamic model of educational effectiveness.

6.1.3. Stages of Effective Teaching Identified in the Maldives

Stage 1: Basic Elements of Direct Teaching

At the beginning stage of effective teaching, the primary focus is on the foundational elements of direct instruction. This stage predominantly emphasizes the quantitative aspects of teaching, such as time management, application, and structuring. Teaching behaviours observed at this stage align with fundamental classroom management techniques, including establishing routines and organizing structured activities. These basic practices are essential for creating a well-ordered and conducive learning environment (Rosenshine & Stevens, 1986). This means that at this stage, teachers are primarily concerned with establishing a stable classroom environment and ensuring that instructional time is used efficiently. The focus on time management and application indicates an emphasis on creating a predictable and organized learning experience for students, which can help in minimizing disruptions and maximizing engagement (Rosenshine & Stevens, 1986). Teachers in this stage are likely to employ straightforward instructional strategies that facilitate clear and structured delivery of content.

Stage 2: Incorporating Aspects of “Quality” in Direct Teaching

Stage 2 is characterized by a shift towards improving the quality of direct instruction. This stage involves an incremental progression from basic classroom management and use of teaching routines (as with teachers in Stage 1) now to a focus on refining key aspects of teaching associated with the direct and active teaching approach, specifically questioning, application, and structuring behaviours. Teachers at this stage are able to implement more sophisticated questioning techniques, incorporating both process questions (which encourage deeper thinking about concepts) and product questions (which assess specific knowledge and understanding). These improvements may contribute to increased student engagement and comprehension. This means that Stage 2 reflects a critical development in teaching practices, where educators move beyond basic instructional techniques to focus more on the quality aspects of their teaching practices and interactions with students. The introduction of higher-level questioning indicates an emphasis on stimulating students’ cognitive processes and encouraging active participation in the learning process.

Stage 3: Transitioning from Direct to Active Teaching

Stage 3 represents a pivotal shift in teaching practices, moving from a focus on direct instruction to more interactive and student-centred teaching methods. At this stage, teachers begin to incorporate interactive elements into their lessons, which promotes greater student participation and engagement. This transition is marked by a noticeable improvement in the use of application and questioning skills, particularly with regard to their focus and quality dimensions. Teachers start to integrate more dynamic teaching techniques that actively involve students in the learning process (Kyriakides et al., 2009). However, despite these advances, the application of fully developed constructivist and differentiated instructional strategies remains limited. This indicates that while teachers are beginning to embrace more advanced teaching methods, they are still in the early stages of adopting these complex approaches.

Stage 4: Active Teaching and Progression Towards Advanced Instruction

Building on the active learning strategies introduced in Stage 3, Stage 4 sees the integration of constructivist approaches and a greater emphasis on student-centred methods, aligning with Hattie’s (2009) focus on creating environments that foster active engagement. Stage 3 introduces active learning strategies and interactive teaching methods. Building on these strategies, Stage 4 is concerned with the integration of constructivist approaches and a greater emphasis on student-centred methods, aligning with Hattie’s (2009) focus on creating environments that foster active engagement. Stage 4 also represents a significant development in teaching practices, where teachers exhibit a sophisticated understanding of active teaching principles. At this stage, educators skilfully blend direct instruction with constructivist strategies, showing proficiency in employing a diverse range of questioning techniques, structuring activities, and managing classroom interactions. This progression reflects a more advanced level of instructional practice, where the emphasis is placed on creating a supportive learning environment that promotes student engagement and active participation (Kyriakides et al., 2009).

Stage 5: Differentiated Teaching and Constructivist Approaches

While Stage 4 emphasizes active teaching and student engagement, Stage 5 represents a deeper commitment to meeting individual student needs through differentiated instruction and constructivist strategies. Stage 5 is characterized by the full integration of differentiated teaching strategies and constructivist approaches. Teachers at this stage are skilful at moulding their instruction to meet the diverse needs of their students, employing a range of techniques to ensure that all students are actively engaged in the learning process (Tomlinson, 2001). In addition to differentiating tasks based on student ability, teachers are also incorporating advanced questioning and application skills, as well as modelling behaviours that promote deeper understanding and critical thinking (Slavin & Cooper, 1999). This stage represents a significant achievement in teaching effectiveness, as teachers demonstrate the ability to create a dynamic and inclusive learning environment that supports the academic growth of all students (Kyriakides et al., 2021).

Stage 6: Mastery of Quality Teaching

Stage 6 concludes the teaching progression by mastering these differentiated and constructivist strategies, blending them seamlessly to achieve the highest level of instructional effectiveness. The final phase of effective teaching in the Maldivian context is characterized by the proficiency in botη quantitative and qualitative aspects of teaching. Teachers at this stage exhibit exceptionally high level of proficiency in all dimensions of the DMEE, including frequency, focus, stage, quality, and differentiation. They are capable of impeccably integrating constructivist and differentiated approaches into their instruction, creating a classroom environment that is both supportive and challenging for all students. Teachers at this stage are skilled in modelling complex concepts, fostering student–student interactions, and promoting independent learning. This stage represents the highpoint of teaching effectiveness, where teachers are not only meeting the diverse needs of their students but also actively contributing to their overall academic success (Kyriakides et al., 2021). One could therefore argue that the results of the Saltus model reveal a progression from foundational techniques to advanced instructional strategies, highlighting the complex and evolving nature of teaching and emphasizing the need for continuous professional development to support educators in achieving mastery.

6.2. The Added Value of Classifying Teachers into Levels of Teaching Competences: Explaining Variation on Student Achievement

In the first part of the results section, findings providing support to the construct validity of the developmental scale have been provided. In this part, the significance of the stages of teaching and their relevance to the field of teacher effectiveness is examined. Specifically, we investigated the degree to which categorizing teachers into these six levels accounted for differences in student achievement in English language. Thus, multilevel regression analysis was conducted. The first step was to determine the variance at individual, and class/teacher level without any explanatory variable. Explanatory variables were added at different levels, with interval variables standardized as Z-scores. Grouping variables were coded as dummies with a baseline group (e.g., boys = 0). The models in Table 3 were estimated after excluding the variables with no statistically significant effect at the 0.05 level.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates and standard errors for the analysis of student final achievement (students within teachers).

The following observations arise from Table 3. First, the empty model revealed that the variance at each level reached statistical significance (p < 0.05). It also shows that almost 20% of the total variance of student achievement at the end of the school year was situated at the teacher/class level. In Model 1, the empty model was expanded by adding context variables at the student and teacher levels. Model 1 was found to explain more than 45% of the total variance of student achievement in English language, and most of the explained variance was at the student level. However, more than 35% of the total variance remained unexplained at the student level. Nevertheless, the effects of all contextual factors at student level but gender (i.e., SES and prior knowledge) were statistically significant at 0.05 level. As it was expected, prior knowledge strongly predicted final achievement. At the teacher level, prior knowledge and SES were also found to be associated with final achievement. In Model 2, we examined if classifying teachers into six stages could explain variation in student achievement. Teachers at Stage 3 were the reference group. Thus, five dummy variables were added. The results showed that students of teachers in higher stages performed better. Specifically, the students of teachers at Stages 1 and 2 had the lowest achievement, whereas students of teachers at Stages 4, 5, and 6 had higher achievement than students of Stage 3. Model 2 was able to explain approximately 55% of the total variance, and most of the additional variance explained was at the teacher level.

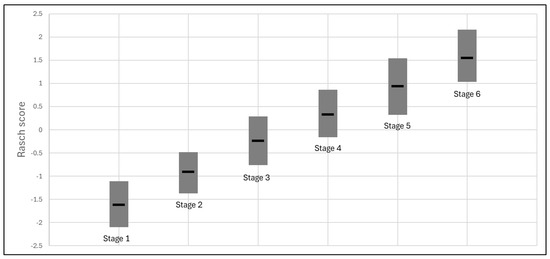

Figure 2 shows the variability in student achievement in the English language at the end of the school year by considering the six groups of students that can be established by considering the stage that their teacher was found to be situated. In this figure, the box represents the interquartile range (IQR), which contains the middle 50% of the data, and the line inside the box indicates the median score. This figure shows that students of teachers who were situated at higher stage were found to perform better than those situated at the lower level and is in line with the results from the multilevel analysis.

Figure 2.

Variability in students’ achievement in English language by considering the stage at which their teacher was found to be situated.

7. Discussion

The stages identified in the Maldives closely match the structure with those identified in the study conducted in other countries including Cyprus and Canada (see Kyriakides et al., 2021). However, the Maldives study identified six stages whereas five stages were found in Cyprus and only four stages in Canada (Kyriakides et al., 2013a). This finding seems to reveal that there is more variation among the skills of teachers in the Maldives and may attributed to the systemic and contextual factors unique to the Maldivian education system. While teacher professional development (TPD) initiatives exist for the Maldives, they often lack alignment with teachers’ specific needs, leading to inconsistent competency outcomes (Fikuree et al., 2022). The Maldives depends heavily on expatriate teachers, mostly from the neighbouring countries like India and Sri Lanka. These teachers often come from different educational and cultural backgrounds, which can lead to differences in how they teach and engage with students Also, the Maldives’ geography—with around 200 inhabited islands spread across a large area and widely disperse—makes it difficult to provide equal access to teacher training and learning resources, especially in the more remote outer islands and atolls. As a result, there are clear differences in teacher qualifications and effectiveness across the islands (Di Biase & Maniku, 2020). Nevertheless, the reasoning behind the stages of effective teaching stayed the same, with Stage 5 in Cyprus closely resembling the characteristics of Stage 6 in the Maldives, particularly in its emphasis on teaching methods rooted in the constructivist approach (E. Fox & Riconscente, 2008). This final stage in both contexts involved qualitative characteristics of factors such as modelling, orientation, and student-centred teaching strategies (Hattie, 2009; Pianta & Allen, 2008), all central to constructivist teaching practices (E. Fox & Riconscente, 2008). These findings seem to suggest that, despite regional differences, the key components of effective teaching can be applied across different cultural and geographical settings.

The introduction of these stages also provides a structured way to understand the development of teaching practices (Kyriakides et al., 2021). These stages are not only sequential but also build upon each other, emphasizing the importance of progressing through each stage to achieve higher levels of effectiveness, providing a more balanced understanding of how teachers evolve in their teaching methods and the associated impacts on student learning outcomes (Berliner, 1994; Hattie, 2009; Kyriakides et al., 2009). For instance, Stage 1, which focuses on basic direct instruction, is essential for building the foundational skills needed for subsequent stages, where teachers begin to adopt more complex strategies (Schwille et al., 2007). In this sense, the stages are not isolated but rather represent a progression of teaching practices that are interrelated (Schweisfurth, 2011).

Moreover, the findings from the multilevel regression analysis revealed that teachers who demonstrated advanced instructional strategies had the greatest impact on student achievement gains. This reinforces the notion that more sophisticated teaching methods lead to improved student learning outcomes as supported by previous empirical studies and meta-analyses of studies on effective teaching (e.g., Hattie, 2009; Kyriakides et al., 2013b; Marzano, 2017). Teachers at the lower stages, while still contributing to student learning, were shown to have a lesser impact on enhancing student achievement in English language compared to those at higher stages. These findings suggest that progression through the stages of effective teaching is essential for maximizing student learning outcomes and achieving higher levels of educational effectiveness (Kyriakides et al., 2013a). Thus, the findings of this study have some implications for research on teacher professional development. More specifically, these findings provide support to the argument that professional development programs should be adapted to support teachers progress through these stages of effective teaching. For teachers in the early stages (Stage 1), professional development should concentrate on developing fundamental classroom management skills and applying basic direct teaching techniques, such as structuring and application (Marzano & Marzano, 2003; Rosenshine, 2012). As teachers advance through the stages, training should shift towards more complex teaching skills, such as differentiated instruction, higher-order questioning, and factors that are in line with constructivist teaching approach such as modelling and orientation (Kyriakides et al., 2013a). These strategies are integral to promoting deeper student engagement and critical thinking. A gradual transition from basic to more sophisticated teaching practices may better equip teachers to enhance student learning outcomes, as supported by research on teacher professional development.

8. Conclusions

8.1. Implications for Policy and Practice

This study revealed that by taking student outcomes in English language as effectiveness criteria, students of teachers in higher stages outperformed those of teachers in lower stages. Thus, one could argue that students’ achievement may be improved through supporting teachers to move from the stage of teaching that they were found to be situated to the next more challenging stage. Hence, education policymakers should consider making use of these results when designing teacher professional development programs. Educational policies should also prioritize continuous professional development, focusing on teachers at different stages of their careers. In the Maldivian context, policies should emphasize the integration of constructivist and differentiated instructional approaches into the national curriculum, encouraging a shift towards more student-centred teaching practices. This shift may promote a learning environment where students are more engaged, and their academic achievement is improved (Kyriakides et al., 2018). Moreover, these policies may support the creation of collaborative professional learning communities (Hord, 1997), where teachers can share best practices, reflect on their teaching methods, and learn from one another. In the Maldives, adopting such communities can help address the specific needs of local teachers, eventually improving the quality of education and promoting student learning outcomes. More specifically, teachers participating in TPD courses should be supported in order to develop and implement their own action plans which should be concerned with the teaching skills that are found to be situated in their own stage. This may help them move to the next more demanding stage and improve both their teaching practice and the learning outcomes of their students.

8.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

In the final part of this section, we discuss the main limitations of the study and offer suggestions for future research. First, the data on teaching quality were based on a single measure (i.e., student questionnaire). Future studies could also incorporate multiple measures of teaching effectiveness, including classroom observations, student feedback, and peer assessments, to provide a more accurate and holistic assessment of teaching quality (Creemers & Kyriakides, 2010). This multi-method approach would enhance the validity of the findings and may offer a more comprehensive understanding of effective teaching. While the use of student questionnaires to measure teaching quality in this study was found to provide valid data, it is important to recognize the limitations of relying on only one source of data for measuring the eight factors of DMEE and their dimensions. This implies that studies testing the generalizability of the results of this study should attempt to use multiple methods for measuring quality of teaching since, in some countries (e.g., Ghana), data emerging from student ratings were not able to detect effects of teacher factors on student achievement, whereas observation data were able to detect effects (Azigwe et al., 2016).

Second, the results of this study cannot support that progression happens in a sequential manner, moving from one stage to the next more demanding (Dall’Alba & Sandberg, 2006). While teachers may exhibit varying competencies at different levels of experience, identifying differences in their skills does not necessarily mean that progression from one level to another happens in a sequential manner. Therefore, longitudinal studies are needed in order to provide more comprehensive insights by tracking teachers’ progression through the stages over time, thus providing a clearer understanding of how teaching practices evolve (see Kyriakides et al., 2017). Such studies may help us find out whether the stages identified in this study remain stable or fluctuate over time, offering a more dynamic view of teacher professional development. While the findings of this study are promising, it is early to assert that the stages identified can be directly applied to teacher professional development programs without further research. To fully understand the practical utility of these findings, experimental studies are necessary to assess the effectiveness of stage-based professional development interventions in real-world educational settings (Kyriakides et al., 2013a). Longitudinal studies could also track the impact of targeted professional development programs on teachers’ progression through the stages and their subsequent impact on student learning outcomes. Such studies may provide valuable insights into the long-term benefits and challenges of implementing stage-based training models. This research would also offer critical feedback on whether the identified stages align with teachers’ actual developmental curves and help refine teacher training approaches to maximize their effectiveness (Creemers et al., 2013b).

Finally, experimental studies should also investigate the effectiveness of professional development programs which can be designed by considering the fact that teachers are situated in different stages. Experimental designs, such as randomized controlled trials, could provide valuable insights into whether targeted interventions may assist teachers’ progression from lower to higher stages. By measuring the effect of these programs on improving teaching skills and, through that, on student achievement, researchers could also examine the value of stage-based TPD courses in promoting quality in education. Moreover, such studies may identify factors which contribute to teacher improvement, allowing for the refinement of professional development strategies. Longitudinal experimental studies would be particularly useful to track these effects over time and investigate the sustainability of teacher improvement programs (Pianta & Allen, 2008; Kyriakides et al., 2024b).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.K., H.S.M. and E.C.; methodology, L.K., H.S.M. and E.C.; software, L.K., H.S.M. and E.C.; validation, L.K. and H.S.M.; formal analysis, L.K., H.S.M. and E.C.; investigation, L.K. and H.S.M.; resources, L.K. and H.S.M.; data curation, L.K., H.S.M. and E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.K., H.S.M. and E.C.; writing—review and editing, L.K., H.S.M. and E.C.; visualization, L.K., H.S.M. and E.C.; supervision, L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Ministry of Education, Maldives, and approved by the Ministry of Education for collecting information from schools. Approval was obtained on the 7th of July 2019 for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and institutional restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EER | Educational effectiveness research |

| DMEE | Dynamic Model of Educational Effectiveness |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| TPD | Teacher professional development |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

References

- Adams, R. J., & Khoo, S. T. (1996). ACER quest: The interactive test analysis system. (Version 2.1). Australian Council for Educational Research. Available online: https://research.acer.edu.au/measurement/3/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Andrich, D. (1988). A general form of Rasch’s extended logistic model for partial credit scoring. Applied Measurement in Education, 1(4), 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, P., & Kyriakides, L. (2013). A dynamic integrated approach to teacher professional development: Impact and sustainability of the effects on improving teacher behaviour and student outcomes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azigwe, J. B., Kyriakides, L., Panayiotou, A., & Creemers, B. P. M. (2016). The impact of effective teaching characteristics in promoting student achievement in Ghana. International Journal of Educational Development, 51, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azkiyah, S. N., Doolaard, S., Creemers, B. P., & Van Der Werf, M. P. C. (2014). The effects of two intervention programs on teaching quality and student achievement. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 49(2), 4–11. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1100411 (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Berliner, D. (1994). Expertise: The wonder of exemplary performances. In J. Mangieri, & C. Block (Eds.), Creating powerful thinking in teachers and students: Diverse perspectives (pp. 161–186). Harcourt Brace College. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/29686158/Expertise_The_wonders_of_exemplary_performances (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Bond, T. G., & Fox, C. M. (2001). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, J., & Good, T. L. (1986). Teacher behaviour and student achievement. M. C. Wittrock, Ed.In Handbook of research on teaching, 3rd ed.; MacMillan. pp. 328–375. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED251422.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Burden, P. R. (1979). Teachers’ perceptions of the characteristics and influences on their personal and professional development. The Ohio State University. [Google Scholar]

- Burden, P. R. (1982, February 16). Professional development as a stressor [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting of the Association of Teacher Educators, Phoenix, AZ, USA. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED218263 (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Carter, E., Molina, E., Pushparatnam, A., Rimm-Kaufman, S., Tsapali, M., & Wong, K. K.-Y. (2024). Evidence-based teaching: Effective teaching practices in primary school classroom. London Review of Education, 22(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C., Muijs, D., Reynolds, D., Sammons, P., & Teddlie, C. (2016). The Routledge international handbook of educational effectiveness and improvement. Research, policy, and practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creemers, B. P. M., & Kyriakides, L. (2008). The dynamics of educational effectiveness: A contribution to policy, practice and theory in contemporary schools. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creemers, B. P. M., & Kyriakides, L. (2010). Using the dynamic model to develop an evidence-based and theory-driven approach to school improvement. Irish Educational Studies, 29(1), 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creemers, B. P. M., & Kyriakides, L. (2012). Improving quality in education: Dynamic approaches to school improvement (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creemers, B. P. M., Kyriakides, L., & Antoniou, P. (2013a). A dynamic approach to school improvement: Main features and impact. School Leadership and Management, 33(2), 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creemers, B. P. M., Kyriakides, L., & Antoniou, P. (2013b). Teacher professional development for improving quality of teaching. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Alba, G., & Sandberg, J. (2006). Unveiling professional development: A critical review of stage models. Review of Educational Research, 76(3), 383–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. Available online: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Effective_Teacher_Professional_Development_REPORT.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Biase, R., & Maniku, A. A. (2020). Transforming education in the Maldives. In P. M. Sarangapani, & R. Pappu (Eds.), Handbook of education systems in South Asia (pp. 233–246). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimosthenous, A., Kyriakides, L., & Panayiotou, A. (2020). Short- and long-term effects of the home learning environment and teachers on student achievement in mathematics: A longitudinal study. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 31(1), 50–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyfus, H. L., & Dreyfus, S. E. (1980). A five-stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition. University of California, Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Elboj, C., & Niemelä, R. (2010). Sub-communities of mutual learners in the classroom: The case of interactive groups. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 15(2), 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson, K. A., & Smith, J. (Eds.). (1991). Toward a general theory of expertise: Prospects and limits. Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://assets.cambridge.org/97805214/04709/excerpt/9780521404709_excerpt.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Feiman-Nemser, S., & Remillard, J. (1996). Perspectives on learning to teach. In F. B. Murray (Ed.), The teacher educator’s handbook (pp. 63–91). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Fikuree, W., Shina, A., Naseem, I., Mohamed, A., Shougee, M., Shakir, M. I., Ali, H. N., Umar, M., Nishan, F., Mohamed, A., Afeef, H., Adam, A. S., Ahmed, N., Jameel, M., Abdulla, M., Shareef, I., Riyaz, M., Nashida, M., Shoozan, A., … Ahmed, S. (2022). Teaching as a career: Perception, value, and choice in the Maldives [Research report]. Maldives National University. Available online: https://mnu.edu.mv/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Teaching-as-as-Career-Research-Report.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Fox, E., & Riconscente, M. (2008). Metacognition and self-regulation in James, Piaget, and Vygotsky. Educational Psychology Review, 20, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, R. (2001). Constructivism examined. Oxford Review of Education, 27(1), 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresko, B., & Nasser, F. (2001). Interpreting student ratings: Consultation, instructional modification, and attitudes towards course evaluation. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 27, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, F., & Bown, O. (1975). Becoming a teacher. In K. Ryan (Ed.), Teacher education (74th yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, Part 2, pp. 25–52). University of Chicago Press. Available online: https://pdfcoffee.com/becoming-a-teacher-by-frances-fuller-amp-oliver-bown-1975--pdf-free.html (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Fuller, F. F. (1969). Concerns of teachers: A developmental conceptualization. American Educational Research Journal, 6(2), 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge. Available online: https://inspirasifoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/John-Hattie-Visible-Learning_-A-synthesis-of-over-800-meta-analyses-relating-to-achievement-2008.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Hord, S. M. (1997). Professional learning communities: Communities of continuous inquiry and improvement. SEDL. Available online: https://sedl.org/pubs/change34/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Keeves, J. P., & Alagumalai, S. (1999). New approaches to measurement. In G. N. Masters, & J. P. Keeves (Eds.), Advances in measurement in educational research and assessment (pp. 23–42). Pergamon. [Google Scholar]

- Klieme, E., Pauli, C., & Reusser, K. (2009). The Pythagoras study: Investigating effects of teaching and learning in Swiss and German mathematics classrooms. In T. Janík, & T. Seidel (Eds.), The power of video studies in investigating teaching and learning in the classroom (pp. 137–160). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakides, L., Archambault, I., & Janosz, M. (2013a). Searching for stages of effective teaching: A study testing the validity of the dynamic model in Canada. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 48(2), 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakides, L., Charalambous, C. Y., & Antoniou, P. (2024a). Integrating subject-generic and subject-specific teaching frameworks: Searching for stages of teaching in mathematics. ZDM Mathematics Education, 56, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, L., Christoforidou, M., Panayiotou, A., & Creemers, B. P. M. (2017). The impact of a three-year teacher professional development course on quality of teaching: Strengths and limitations of the dynamic approach. European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(4), 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, L., Christoforou, C., & Charalambous, C. Y. (2013b). What matters for student learning outcomes: A meta-analysis of studies exploring factors of effective teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 36, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, L., Creemers, B., & Charalambous, E. (2018). Equity and quality dimensions in educational effectiveness (Vol. 8, Policy Implications of Research in Education series). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, L., Creemers, B. P. M., & Antoniou, P. (2009). Teacher behaviour and student outcomes: Suggestions for research on teacher training and professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(1), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, L., Creemers, B. P. M., Antoniou, P., Demetriou, D., & Charalambous, C. (2015). The impact of school policy and stakeholders’ actions on student learning: A longitudinal study. Learning and Instruction, 36, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, L., Creemers, B. P. M., Panayiotou, A., & Charalambous, E. (2021). Quality and equity in education: Revisiting theory and research on educational effectiveness and improvement. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, L., Creemers, B. P. M., Panayiotou, A., Vanlaar, G., Pfeifer, M., Gašper, C., & McMahon, L. (2014). Using student ratings to measure quality of teaching in six European countries. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(2), 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, L., Ioannou, I., Charalambous, E., & Michaelidou, V. (2024b). The dynamic approach to school improvement: Investigating duration and sustainability effects on student achievement in mathematics. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 35(3), 342–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoulides, G. A., & Drezner, Z. (1999). A procedure for detecting pattern clustering in measurement designs. In M. Wilson, & G. Engelhard Jr. (Eds.), Objective measurement: Theory into practice (Vol. 5). Ablex Publishing Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Marzano, R. J. (2017). The new art and science of teaching: More than fifty new instructional strategies for academic success. Solution Tree Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marzano, R. J., & Marzano, J. S. (2003). The key to classroom management. Educational Leadership, 61(1), 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mockler, N. (2022). Teacher professional learning under audit: Reconfiguring practice in an age of standards. Professional development in education, 48(1), 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijs, D., Kyriakides, L., van der Werf, G., Creemers, B., Timperley, H., & Earl, L. (2014). State of the art—Teacher effectiveness and professional learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(2), 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musthafa, H. S., & Kyriakides, L. (2023). Using student ratings and external observations to detect the effects of quality of teaching on student learning outcomes: A longitudinal study in the Maldives. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 1–17. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02188791.2023.2261648 (accessed on 17 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Newman, K. K. (1978). Middle-aged, experienced teachers’ perceptions of their career development [Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University]. OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center. Available online: http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1487081370610263 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- NIE. (2011). The national curriculum framework. National Institute of Education: Ministry of Education, Maldives. Available online: https://nie.edu.mv/national-curriculum-framework/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Panayiotou, A., Kyriakides, L., Creemers, B. P. M., McMahon, L., Vanlaar, G., Pfeifer, M., Rekalidou, G., & Bren, M. (2014). Teacher behavior and student outcomes: Results of a European study. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 26, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, P. L., Marx, R. W., & Clark, C. M. (1978). Teacher planning, teacher behavior, and student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 15(3), 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R. C., & Allen, J. P. (2008). Building capacity for positive youth development in secondary school classrooms: Changing teachers’ interactions with students. Social Policy Report, 22(2), 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praetorius, A. K., Klieme, E., Herbert, B., & Pinger, P. (2018). Generic dimensions of teaching quality: The German framework of three basic dimensions. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50(3), 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenshine, B. (2012). Principles of instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American Educator, 36(1), 12–19. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ971753.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Rosenshine, B., & Stevens, R. (1986). Teaching functions. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 376–391). Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sancar, R., Atal, D., & Deryakulu, D. (2021). A new framework for teachers’ professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 101, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J. (1994). Human competence at work: An interpretative approach. BAS. [Google Scholar]

- Scheerens, J. (2013). The use of theory in school effectiveness research revisited. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 24(1), 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerens, J. (2016). Educational effectiveness and ineffectiveness: A critical review of the knowledge base. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, A. H. (1998). Toward a theory of teaching in context. Issues in Education, 4(1), 1–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweisfurth, M. (2011). Learner-centred education in developing country contexts: From solution to problem? International Journal of Educational Development, 31(5), 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwille, J., Dembélé, M., & Schubert, J. (2007). Global perspectives on teacher learning: Improving policy and practice. International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP) UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000150261 (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Sims, S., Fletcher-Wood, H., O’Mara-Eves, A., Cottingham, S., Stansfield, C., Goodrich, J., Van Herwegen, J., & Anders, J. (2023). Effective teacher professional development: New theory and a meta-analytic test. Review of Educational Research, 95(2), 213–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R. E., & Cooper, R. (1999). Improving intergroup relations: Lessons learned from cooperative learning programs. Journal of Social Issues, 55(4), 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Anderson, R. C., Lin, T.-J., Morris, J. A., Miller, B. W., Ma, S., Thi Nguyen-Jahiel, K., & Scott, T. (2022). Children’s engagement during collaborative learning and direct instruction through the lens of participant structure. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 69, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms (2nd ed.). ASCD. Available online: https://rutamaestra.santillana.com.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Classrooms-2nd-Edition-By-Carol-Ann-Tomlinson.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Trotter, R. (1986). The mystery of mastery. Psychology Today, 20(7), 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2017). Education for all: Achievements and challenges in the Maldives. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2021, June 30). Early learning and general education in the Maldives: Performance, challenges, and policy options. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/889841625048965345/pdf/Early-Learning-and-General-Education-in-the-Maldives-Performance-Challenges-and-Policy-Options.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Wright, B. D. (1985). Additivity in psychological measurement. Measurement and Personality Assessment, 2(2), 101–112. Available online: https://www.rasch.org/memo33b.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).