Abstract

This study explores the use of a theatre project to enhance reading competencies among students with special educational needs (SENs) in inclusive classrooms. The project, titled “Stop Bullying! A Theatre Project”, aimed to improve students’ reading skills through dramatised engagement with texts, with a particular focus on promoting literacy and social interaction. Employing a Design-Based Research (DBR) methodology, the study involved iterative cycles of implementation and data collection. Participants, including students with varying reading abilities, engaged in theatrical activities that incorporated reading strategies such as reading aloud, paired reading, and choral reading—each designed to support comprehension, fluency, and reading confidence. Findings from multiple cycles indicated improvements in students’ social dynamics, including stronger peer interactions and increased group cohesion. While quantitative reading assessment data showed only modest gains in reading performance, qualitative observations revealed significant improvements in reading skills and social interactions during collaborative performances. The study concludes that a theatre-based approach can effectively support reading development while fostering a more inclusive and supportive classroom environment.

1. Introduction

Literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society.(UNESCO, 2025)

The above introductory quotation highlights that literacy skills, including reading, speaking, and interpreting, are fundamental skills for educational success and personal growth. However, many students with and without special educational needs (SENs) struggle to develop adequate proficiency in these areas (OECD, 2019). SEN students often require tailored instruction, which poses significant challenges for teachers in inclusive classrooms. This study aims to identify effective practices for supporting SEN students in their literacy development and examines how these practices are implemented in different educational contexts. In this context, language teachers should focus on promoting literacy for every student in order to close the gap between highly and poorly literate citizens.

In 2007, Germany signed the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which was then ratified in 2008. The convention officially came into force in 2009. In Germany, the implementation of inclusive education presents particular challenges due to the historically developed, highly differentiated school system, which separates students based on their academic ability and other criteria (Booth & Ainscow, 2002).

Persons with disabilities are not excluded from the general education system on the basis of disability, and […] children with disabilities are not excluded from free and compulsory primary education, or from secondary education, on the basis of disability.(United Nations, 2006)

Bullying in schools is a major problem in most countries. Bullying involves the intentional use of physical or psychological violence against an individual, which is repeated over time, typically by classmates, and in some cases even by teachers, in situations where there is a power imbalance (Fischer et al., 2024; OECD, 2015, 2017). This form of violence is widespread: one in two fifth graders experiences some form of violence at school, and one in six students is subjected to bullying. The PISA Report (OECD, 2017) also highlights that bullying is a global issue, as academic learning cannot take place if students with and without SENs do not feel safe and secure in school.

Fostering a sense of community in inclusive learning contexts can help mitigate these issues. A school community includes students, teachers, pedagogues, technical and administrative staff, and parents—all of whom contribute to the learning environment. Students with SENs may thrive or fall behind depending on whether the school climate supports their academic efforts.

The term inclusion in the school context stands for learning and working together within a school community. For teaching, this means that the individual learning requirements of all students are recognized in an appreciative manner and are taken into account in the systematic design of learning opportunities.(translated by author from Giera et al., 2024)

The author who coined the term “inclusion in the school context” (see quotation) defined each term: The term “school context” refers to the environment in which the school administration oversees students and the pedagogical staff. “Teaching” describes the framework in which the teacher or pedagogical team is responsible for learning activities, both within the school and in local settings. “Collaborative learning” involves interdisciplinary, process-oriented learning in inclusive environments. A “systematic design of learning opportunities” includes the planned creation, implementation, and evaluation of learning arrangements that are tailored to individual needs. “Processual” refers to the gradual phases of skill development. “Individual learning conditions” are personal traits, such as learning pace, concentration, or background, that affect a student’s learning. “Appreciative recognition” means acknowledging and embracing individual learning preferences and needs as part of diversity work.

Shared learning experiences can strengthen bonds within the community, and activities such as theatre play have been shown to positively impact group cohesion (Domkowsky, 2011). In L1 education, combining reading with drama pedagogy is not yet common in middle or high schools in Germany. In the international context, drama in inclusive learning settings is implemented but more outside of schools.

Cardol et al.’s (2025) qualitative study examines how Israeli children and parents experience the Haifa International Children’s Theatre Festival as a comprehensive family event, highlighting a reception process that includes play selection, knowledge mediation, participation, celebration, and reflection.

Jónsdóttir and Thorkelsdóttir (2024) explored how participation in Skrekkur, a youth theatre competition in Reykjavík, Iceland, can enhance young people’s well-being and self-esteem through a playbuilding process, with findings from a qualitative case study showing that participants viewed the experience as empowering and beneficial to their personal growth.

The study of Freeman and Welsh (2024) examines the socio-emotional impacts of a summer Readers’ Theatre intervention for public middle school students, focusing on first- and second-generation African immigrant and refugee participants, and highlights themes of culturally based arts engagement, perceived achievement, and the intervention’s influence on school readiness, reading attitudes, and ensemble building. So, there is a practical lack of effective inclusive literacy strategies in schools.

A key challenge is promoting reading in inclusive classrooms through open-learning formats such as theatre. Open-learning formats require a shift in classroom management, especially when students are unaccustomed to high levels of autonomy and reduced teacher guidance. While teachers play a crucial role in influencing the learning outcomes, the importance of classroom leadership is often underestimated. Grounded in Kounin’s (2006) techniques and supported by Hattie’s meta-analyses (2012), effective classroom management (effect size d = 0.52) significantly impacts student achievement. Helmke (2015) also identified it as one of the most influential factors in academic success. For classroom management to be effective, teachers must consistently reflect on and apply strategic methods. However, isolated efforts are not enough—school-wide support is essential. Because students often resist unfamiliar rules, shared school culture and consistency among educators are necessary. To foster self-directed learning, teachers should shift into a guiding role, promote student responsibility, and cultivate a positive feedback culture to enhance students’ self-efficacy. These factors are important for creating a reading and performance space with a warm atmosphere in inclusive classes.

This article seeks to address a central question for current and future SEN educators: How can a theatre project, using drama text about bullying, promote reading competence in inclusive classrooms with heterogeneous reading skills? To answer this general question, the following structure is implemented:

- Section 2 introduces the theoretical framework on reading and presents the reading theatre project.

- Section 3 outlines the research concept and questions.

- Section 4 presents the design and methodology.

- Section 5 discusses findings from three completed project cycles, conducted both inside and outside of schools, in relation to the research questions and hypotheses.

- Section 6 concludes the article by summarising findings and offering implications for future research and practical implementation.

2. Theoretical Framework on Reading (Theatre)

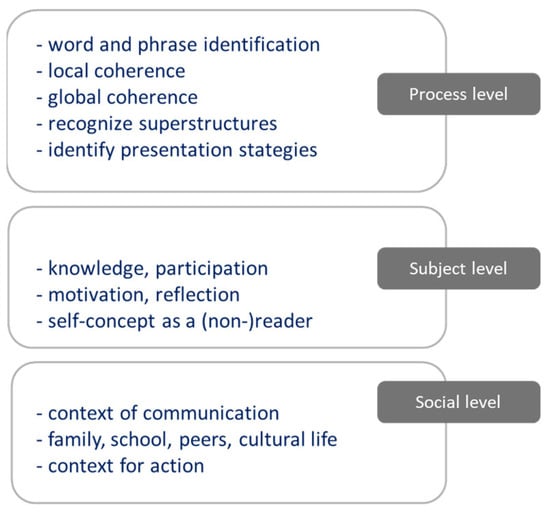

Rosebrock and Nix (2020) understand reading using multiple levels. They emphasise that reading a text requires action on the process level, draws on resources from the subject level, and is connected to the social level of the reader. One example is reading in schools, which is typically linked to specific reading tasks in a classroom setting. In this context, the individual reader (the subject) engages with the text on the process level and is embedded within a social reading environment—the class. To promote reading to adolescents, further motivational approaches are implemented in schools. The approach reading for pleasure does not focus on tasks that are set by teachers (Cremin & Scholes, 2024; Boyask et al., 2024). This approach allows readers to participate in book choices, reading times and lengths, reading support, and self-organised reading tasks. Even reading tasks and environments that are planned by teachers and students in collaboration are encouraged to promote reading at the following three levels: the process, subject, and social levels. To define the three levels of reading more clearly, consider the following descriptions:

At the process level, reading and understanding a text involve several key components of comprehension. First, word and phrase identification is essential, as it allows the reader to recognise individual words and their meanings within the text. Next, local coherence refers to the ability to understand how ideas and sentences are connected within a smaller section of the text, ensuring that the reader can follow the immediate flow of information. Global coherence, on the other hand, involves grasping the overarching message or theme of the entire text, connecting all parts to form a comprehensive understanding. Additionally, recognising superstructures helps the reader identify common organisational patterns in the text, such as narrative or argumentative structures. Finally, identifying presentation strategies enables the reader to understand how the author has chosen to present information—through emphasis, repetition, or rhetorical devices—to convey their message effectively.

Example: A student reads a short story and identifies key vocabulary (word and phrase identification), follows the connections between sentences (local coherence), understands the main theme of the story (global coherence), recognises that the story follows a typical narrative structure (superstructures), and notices the author’s use of repetition to emphasise important ideas (presentation strategies).

At the subject level, several factors contribute to a student’s engagement with reading. Knowledge plays a crucial role, as a solid understanding of the subject matter fosters deeper comprehension and interest. Participation is also important, as active involvement in reading activities reinforces learning and encourages a personal connection to the text. Motivation drives the desire to read, influenced by both intrinsic interests and external encouragement. Reflection allows students to think critically about what they have read, helping them internalise the material. Finally, a student’s self-concept as a reader—or non-reader—significantly impacts their engagement with reading. Those who view themselves as capable readers are more likely to participate and enjoy the process, while those with a negative self-concept may struggle with motivation and confidence.

Example: A student who loves science eagerly reads an article about space exploration (knowledge), participates in class discussions about the article (participation), feels excited to learn more (motivation), reflects on how the information connects to what they already know (reflection), and sees themselves as a capable science reader (self-concept).

At the social level, the context of communication plays a key role in shaping a student’s reading and learning experiences. Family, school, peers, and cultural life all provide important environments in which communication occurs, and reading is either encouraged or discouraged. Within the family, children often receive their first exposure to reading habits, while school serves as a formal setting for developing reading skills. Peers can influence reading attitudes and behaviours, offering either positive or negative reinforcement. Cultural life—including media and societal norms—also shapes the value that is placed on reading. These social environments serve as contexts for action, offering students opportunities to engage in reading-related activities, discussions, and shared experiences that contribute to their overall literacy development.

Example: A student discusses a favourite book with family members at home (family), participates in a school reading group (school), recommends books to friends (peers), and attends a local book festival that promotes reading (cultural life).

In the theatre-based study “Stop Bullying! A Theatre Project”, reading a drama text served as more than just a literary activity—it became a multidimensional approach to literacy development. Combined with the reading levels described above, reading theatre can be understood as follows:

At the process level, students advanced their reading competence by developing local and global coherence, recognising superstructures, and applying the required reading strategies to rehearse scenes meaningfully. This became especially evident when students began acting on stage—positioning themselves, moving around, and transforming text into action. Such performative engagement required more than surface-level decoding; it demanded deep comprehension and scene-based coordination within the group. Dramatic texts have the potential to make reading active, interpretative, and socially situated within collaborative stage work (Boal, 2019; Iser, 1978).

At the subject level, this embodied approach fostered motivation, active participation, and a strengthened self-concept as readers and performers. Students were empowered not only to interpret the text but also to co-construct it creatively, bridging literacy with identity.

At the social level, the collaborative nature of theatre—resolving questions such as “Who stands where and when?”—created opportunities for peer communication and feedback. When performances were shared with parents, educators, classmates, and guests, the project extended beyond the classroom and contributed to a broader school culture. In this way, reading drama texts through performance became a culturally enriching, academically grounded practice that connected individual literacy with collective expression.

3. Research Idea and Research Questions

Engaging with drama texts through theatrical play fosters reading competence on multiple levels. At the process level, it enhances both local and global coherence, requiring students to understand narrative structure, recognise superstructures, and apply reading strategies (Rosebrock & Nix, 2020). The practice of interpreting and rehearsing scenes demands more than simple word decoding; it involves coordinated reading comprehension and situational awareness, as students must collectively resolve questions such as their spatial positioning and timing during performance. The theatre stage functions as a “show-space” (Denk & Möbius, 2017, p. 18), offering both linguistic and non-linguistic means of expression that go beyond passive text reception and encourage action-oriented engagement. Theatre also opens doors to reading and interpreting a drama text in other ways to “better integrate cognitive, emotional and embodied knowledge” (Polido et al., 2025).

At the subject level, theatrical activities promote motivation, self-reflection, and a strengthened self-concept as readers. Students become active participants in the meaning-making process, transforming written text into performative expression and thereby experiencing increased self-efficacy.

At the social level, theatre projects foster peer interaction and collaborative communication (Rathje et al., 2021). When performances are staged for audiences such as parents, teachers, and classmates, they also contribute to a school’s cultural life, creating meaningful contexts for communication and learning.

The overarching research focus in related theatre-based studies centres on how such projects can promote both reading competence and social interaction. Objectives include supporting literacy development, enhancing creativity through scenic interpretation, fostering cooperative learning, and embedding inclusive practices into instructional designs. These projects are often implemented in secondary education settings within German language classes and rely on collaborative planning with teachers and student teachers. Emphasis is placed on designing inclusive learning environments and engaging in continuous reflective processes to assess and improve the educational outcomes. In the theatre cycles described in the following sections, the university-trained special educational need (SEN) trainers did not know which students had SENs and which did not. The only information that was provided was that students with and without SENs wanted to improve their reading skills through a joint theatre project. Therefore, no labelling was possible during the project.

To explore how theatre projects promote reading competencies in inclusive learning groups, three research questions and hypotheses were formulated:

- RQ1: Which reading skills (reading speed and comprehension) do the participating students demonstrate when reading literary texts at the beginning and end of the theatre project, compared with the control group?

H1:

Since the dimensions of reading competence are addressed through scenic play, the reading competence of the intervention group will develop more positively compared with the control group (Rosebrock & Nix, 2020; Denk & Möbius, 2017).

- RQ2: How can participating students receive individual support in reading within a theatre project?

H2:

Reading skills can be promoted through production-oriented literature teaching, and students can be individually supported through scaffolding methods (Rosebrock & Nix, 2020).

- RQ3: How do participating students and trainers promote social interaction within the theatre project?

H3:

Social interaction will improve through scenic play as a joint learning objective (theatre project) (Polido et al., 2025; Rathje et al., 2021; Rosebrock & Nix, 2020; Domkowsky, 2011; Hattie, 2012; Helmke, 2015; Berkeley et al., 2009; Kounin, 2006).

The research and teaching study “Stop Bullying! A Theatre Project” (Giera, 2024), conducted by the author, focuses on improving reading skills and social interaction through a theatre-based intervention that addresses bullying. These reasons were included in the open call to schools and institutions, such as youth clubs, to find participants for this study.

4. Research Design and Methodology

4.1. Desing-Based Research

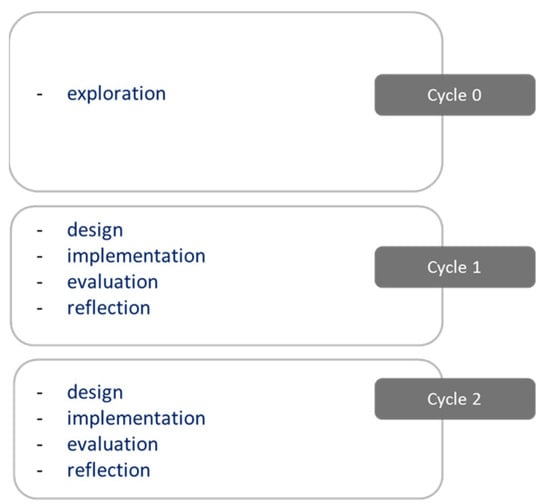

This study employed a Design-Based Research (Philippakos et al., 2021) methodology to iteratively explore and refine a theatre-based literacy intervention, particularly targeting students with diverse reading needs in inclusive classrooms. The diagram (see Figure 1) illustrates the iterative phases of the Design-Based Research (DBR) cycle implemented in the study, beginning with a problem analysis in collaboration with practitioners, followed by the design and implementation of theatre-based literacy interventions, systematic data collection and analysis, and subsequent refinement of teaching practices. This cyclical process emphasises co-construction, continuous feedback, and adaptation to ensure the interventions align with the needs of diverse learners and support inclusive literacy development in real-world educational settings.

Figure 1.

DBR cycles.

DBR was chosen for its dual focus on generating practical educational solutions and theoretical insights through collaboration with practitioners (Philippakos et al., 2021). The intervention, titled “Stop Bullying! A Theatre Project”, was implemented in three distinct cycles (extracurricular, school-based, and control–intervention comparison), each informing the next iteration through feedback and reflective practice. Implemented during the critical transition from primary to lower secondary education (middle schools), the project aims to foster an inclusive learning environment by promoting both literacy development and a sense of community. Central to the research are questions concerning the project’s influence on reading fluency, comprehension, self-efficacy (not presented in this article), and students’ social integration, which were assessed through comparisons between the intervention and control groups.

4.2. Participants and Settings

Schools and youth institutions could apply for this drama project following an open call by the author through her university’s Instagram, LinkedIn, or website. Participants included students aged 11–13 from both extracurricular and comprehensive school settings in Germany. Across all cycles, learners with and without special educational needs (SENs) participated without prior labelling, thus avoiding stigmatisation and promoting inclusive participation. Cycle 0 involved 24 students from a middle school in a class project, cycle 1 included 13 girls in an extracurricular youth centre setting, and cycle 2 expanded to 75 students from three school classes, with 14 in the intervention and 39 in the control group. In cycle 0, the theatre project was collectively coordinated by the class after reading the play script. In cycle 1, the girls from the youth club participated voluntarily in the theatre project during their holidays. In the cycle 2, an entire year group participated in the project and, based on their interests, assigned themselves either to theatre, a sport, or an art project. The year group was thus completely divided into these three groups. All participants reflected diverse reading abilities, including diagnosed dyslexia, multilingual backgrounds, and social–emotional vulnerabilities.

The teaching staff included experienced teachers, special educational need (SEN) trainers, and university students in teacher training. Their roles were not only instructional but also reflective, as they co-designed and adapted the intervention throughout the cycles.

4.3. Theoretical Framework and Pedagogical Foundation

The intervention was grounded in Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, particularly the concept of scaffolding—a process through which learners are supported just beyond their current ability (Vygotsky, 1978). This theory emphasises the role of social interaction in cognitive development and aligns closely with theatre-based learning, which requires collaboration, guided participation, and shared meaning-making. Scaffolding was operationalised in several ways: Paired and choral reading allowed peer-supported decoding and fluency practice. Stage rehearsals embedded reading tasks in real-world contexts, fostering deeper comprehension through embodied learning. Feedback sessions after performances offered timely, constructive dialogue between peers and facilitators, enabling learners to refine both their literacy and performance skills. Reading corners for training the role text provided safe, structured micro-environments for intensive support. Through this scaffolding approach, learners moved from supported rehearsal to confident public performance, building both reading competence and self-efficacy. Boal’s (2019) drama exercises aim to motivate students, whether they view themselves as actors or non-actors.

4.4. Research Instruments and Data Collection

A mixed-methods approach was adopted to enhance data triangulation, thereby increasing the validity of findings and enabling holistic insights into literacy development. Quantitative data were collected using the standardised LGVT 5–12 reading test (Schneider et al., 2017), which assessed a mean score across the items of reading speed, comprehension, and accuracy at three time points: pre-test, post-test, and delayed post-test. All of these items relate to the process level of reading (see Figure 2). Additional qualitative data were needed and included field notes, participant observations without guided items, and open student feedback (frank feedback) collected across all implementation cycles (Mayring, 2010). These inductive data captured emotional engagement, levels of participation, and peer interactions, helping to address both the social and subject levels of reading (Mayring, 2010; Denzin & Lincoln, 2000). All three conducted cycles represent case studies at three different educational institutions (two schools and one youth club).

Figure 2.

Multilevel model of reading (adapted from Rosebrock & Nix, 2020).

4.5. Implementation and Adaptation Through Feedback

Each DBR cycle followed a structure of design, enactment, analysis, and redesign, with feedback loops playing a central role. After the pilot phase (cycle 0), feedback from students and instructors prompted modifications in group structure, rehearsal formats, and reading strategy application. For example, warm-up games were revised to foster better inclusion. Reading tasks were differentiated based on student fluency levels. Reflection check-outs became more structured, incorporating self-assessment prompts. Adaptations in response to feedback helped tailor the intervention to the dynamic needs of each group, thereby embodying the DBR principle of responsive, evidence-based design.

4.6. Alignment with Research Objectives

The research design enabled a comprehensive examination of the study’s key questions: it allowed for the measurement of reading development (RQ1), the observation of individualised scaffolding in practice (RQ2), and the documentation of peer interaction and social growth (RQ3). While the quantitative results indicated modest gains in reading performance, the qualitative findings provided strong evidence of increased motivation, strengthened group cohesion, and improved reading confidence—central objectives of both literacy promotion and inclusive education.

5. Cycle-by-Cycle: Findings from a Multi-Phase Theatre Intervention

5.1. Cycle 0: Beginning in a School

The drama book about bullying in schools Allein! Tatort Schule (translated: Alone. School as a Crime Scene!) by Claudia Kumpfe (2013) is a powerful play that portrays the challenges of school life. The play features 10 female characters and is structured into 20 scenes, spanning 36 pages. With a performance time ranging from 60 to 80 min, it also includes two songs, adding a musical element to the dramatic narrative. The story addresses important themes that are relevant to students, making it both an engaging and impactful play for school settings (Giera, 2024; Schmalenbach et al., 2024).

The project was developed and implemented for the first time by the author while working as a teacher at a middle school. It was carried out with an inclusive seventh-grade learning group consisting of 24 students, including 5 with special needs, 8 who were diagnosed with dyslexia, and 2 with refugee or migration backgrounds. The project focused on the play Alone. School as a Crime Scene!, culminating in a public performance in the local community. The project was integrated into German and homeroom lessons and ran over one school semester during the 2016–2017 academic year, with 90 min weekly sessions.

A check-in was conducted at the beginning of each session, during which the mood of the learning group was assessed. This was followed by a warm-up phase, during which various theatre-related games were introduced to enhance social interaction. This approach was inspired by Augusto Boal’s (2019) Theatre of the Oppressed, in which playful techniques for approaching scenes and actual feelings or problems are used to highlight social injustices and encourage reflection on individual actions. In the check-in phase, classic icebreakers were also conducted: “Ice-breaking activities give participants a creative mindset and positive mood, introducing participants to theatrical techniques and enhancing group cohesion” (Polido et al., 2025). During the exercise phase, scenes were rehearsed on stage by one group, while feedback was provided by another group. A third group practiced reading their roles in pairs, using techniques such as reading aloud, reading together, and tandem reading. Each session was concluded with a check-out, during which reflections on successful aspects of the session were shared, and areas for improvement in the next session were identified. The duration of each phase was adjusted flexibly based on the mood, motivation, and preferences of the group (Schmalenbach et al., 2024).

Only field notes from the author were collected and analysed (Mayring, 2010); no additional data or input from research colleagues were gathered for this initial project. Based on cycle 0, the following hypotheses could be tentatively confirmed in this explorative case study:

- H1: The dimensions of reading competence are addressed through scenic play.

- H2: Reading skills can be promoted through production-oriented literature teaching and individual scaffolding methods.

- H3: Social interaction improved through the scenic play, which served as a joint learning objective in the inclusive classroom.

After returning to the university, the author and SEN teacher initiated two additional cycles—conducted both outside and inside schools—to collect data for the study “Stop Bullying! A Theatre Project”, which began in 2021.

5.2. Cycle 1: Outside of School

In July 2021, an extracurricular test phase of the project took place in a youth club. This voluntary vacation project involved 13 girls of different ages, varying German (L2) language skills, and diverse migration backgrounds. The participants took part over the course of one vacation week. As in cycle 0, the group worked on and performed the play Alone. School as a Crime Scene! by Kumpfe (2013). Two trained SEN teachers conducted participant observation and took field notes to document the process and outcomes.

The summary of both field notes revealed strong group cohesion, which persisted even 1.5 years after the project’s completion. Notably, the participants did not know each other prior to the project. The analysed field notes (Mayring, 2010) confirmed that although some students initially refused to read aloud, they later became actively engaged.

- In Case A, two eight-year-olds who initially shared a role requested their own roles after two days.

- In Case B, an older sister observed her younger sibling reading aloud throughout the entire week.

- In Case C, a student with dyslexia, who initially refused to read, gained confidence through tandem reading and eventually performed on stage after reading to her mother.

These examples highlight the transformative effect of the project on participants’ attitudes toward reading and performing.

As the project progressed, reading the play became increasingly accepted by all participants. The warm-up activities fostered social interaction, helping everyone feel integrated into the group despite the age differences (8–13 years). During the exercises, students received reading support through approaches such as reading aloud, paired reading, and choral reading. The “reading corners” allowed participants to rehearse their roles in a protected space with peers and, at times, with one of the university trainers.

At the end of each reading session, a stage rehearsal was conducted on a provisional stage to showcase the participants’ progress in reading and acting. During these sessions, the students naturally discussed scene interpretations, asking questions such as “Where should I stand?”, “How should I move my body?”, or “With what emotion should I read/play this line?”. The participants switched between the roles of performers and audience members to receive feedback on their performance.

Feedback from audiences can provide valuable information on the effectiveness of a production’s story, characters, and overall presentation. This feedback can help creators identify strengths and weaknesses in their work and make adjustments accordingly. By paying attention to audience reactions, producers and directors can ensure that their productions are engaging and captivating for viewers.(Sokari, 2025, p. 44)

At the end of each theatre day, a check-out was held to set goals for the next day—both for individuals and the group. All participants consistently arrived on time and voluntarily practiced their roles and songs at home. This confirmed that the procedures from cycle 0 were also effective in cycle 1.

At the end of the week, participants invited friends and family to watch their performance. Each student could decide whether to perform with or without the script in hand. The trainers observed that some students used the text for longer monologues, while others held the script for reassurance but did not refer to it during the performance. The group received applause from the audience, as well as flowers, in recognition of their motivation and willingness to read, act, and perform during their vacation. The positive feedback from the audience was central for the students because they did not regularly play on stage.

In a feedback session following the theatre project, every participant indicated that they would recommend the project to other children and young people. The only criticism was that the project felt too short—many students expressed a desire for a longer duration.

A key takeaway from this cycle was the importance of maintaining structure. Warm-ups were well received and served as effective icebreakers, helping participants connect on a personal—and often humorous—level. The reading corners provided a secure environment to work on the drama text, offering individualised support. Some students had strong reading fluency, preferred fast-paced acting, could memorise their lines quickly, and actively contributed to discussions about staging, props, and costumes. Others needed more support—working in pairs, using their finger to guide reading, starting slowly, repeating lines for fluency, and asking for the meaning of unfamiliar words. This group also received positive feedback as they progressed from the reading corners to the stage. All students showed noticeable improvement from scene to scene and stage to stage. Eventually, a full performance was created, where every student performed using their own reading resources. Regarding the hypotheses, the following observations were made:

- : This cycle (cycle 1) confirmed that the dimensions of reading competence were addressed through scenic play. The reading competence of the intervention group developed positively, but since no control group was included in this cycle, comparative conclusions could not be drawn. It remained an exploratory single-case study (see H1).

- : Reading skills were supported through specific approaches such as paired reading, reading aloud, and choral reading (see H2).

- : Social interaction was significantly improved through the theatre project. While the girls previously only knew each other from the neighbourhood, they spent a week together during the project, supported each other in reading and performing, and formed new friendships. According to the trainer, some of these friendships persisted even 1.5 years later (see H3).

The objective after cycles 0 and 1 was to implement the project within a school setting that included a control group for comparison.

5.3. Cycle 2: In a School

This study was conducted in a comprehensive school, specifically targeting seventh-grade students. A total of 75 students from three different classes were invited to participate. In these classes, students with and without special educational needs (SENs) were learning together. Of the 75 students, 53 agreed to participate in the data collection, although all students were involved in the project.

Participants were given the option to join one of three activities: the theatre project, which formed the intervention group (n = 14), sports, or art activities, which served as control groups (n = 39). This design enabled a comparison between the intervention and control groups to evaluate the impact of the theatre project on students’ development and skills. No personal data or background information were collected. The university team was only informed that students with very low reading performances and SENs were present in all three classes.

The theatre project intervention took place over a period of ten weeks, from August to October 2021. During this time, detailed field notes were recorded to capture observations of student participation, group dynamics, and the progression of the project. These notes served as qualitative data to complement the quantitative assessments that were conducted at different stages of the intervention.

As part of the Design-Based Research (Philippakos et al., 2021) approach, adjustments were made after cycle 1 to better implement the project in the school context two months later. Specifically, an evaluation was conducted to determine which games from cycle 1 should be retained, with a focus on those that were easy to implement and had a positive influence on group dynamics. Additionally, more time was built into the project schedule to ensure a smoother and more effective implementation.

The methods that were used for data collection included several testing instruments. The LGVT 5–12 reading test (Schneider et al., 2017), a standardised reading assessment in German, was employed to evaluate the reading abilities of the participants. The test is normed for grades 5 through 12, with different T-values for each grade level. This tool enabled the collection and interpretation of reading data across the relevant age group.

The analysed results of the LGVT reading test were compared graphically in the context of the norm-referenced scoring that is used in this test. T-values are plotted on the graph, with labels for different performance ranges: “below average” (T-values of 20 to 39), “lower middle range” (T-values of 40 to 49), “upper middle range” (T-values of 50 to 59), “above average” (T-values of 60 to 69), and “very high” (T-values of 70 to 80). These T-scores indicate varying performance levels across the three parameters of the LGVT reading test:

- Reading comprehension;

- Reading speed;

- Reading accuracy.

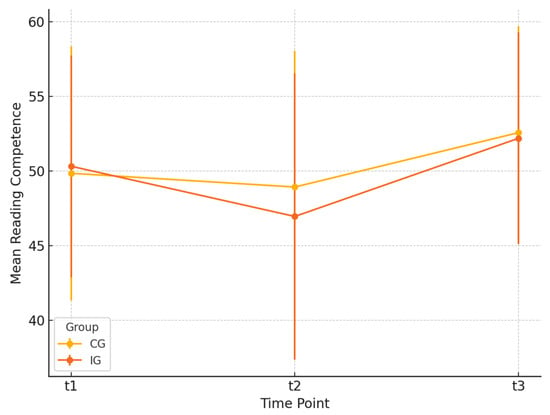

When these three T-scores—comprehension, speed, and accuracy—are combined, they represent the overall reading competence (see Table 1, Figure 3). Three measurements were conducted using the LGVT, a reading test prior to the theatre project (t1), immediately after the theatre project (t2), and three months post-project (t3), for both the control and intervention groups. Additionally, field notes recorded in a research diary by the university SEN trainer were utilised to provide qualitative insights into the group dynamics and progress during the intervention phases between screenings t1 and t2.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for reading competence based on group and time point.

Figure 3.

Reading competence over time by group in cycle 2.

5.3.1. Reading Screenings with Standardised Reading Test

At the start of the theatre project, the first screening (t1, August 2021) was conducted. This included the administration of the LGVT reading test. The initial reading assessment provided baseline data to evaluate the impact of the theatre project on reading skills throughout the study.

The second screening took place one day after the theatrical performance in October 2021 (t2). During this phase, the students completed the LGVT reading test again to assess any improvements in their reading skills. This post-performance assessment offered a comprehensive evaluation of the intervention’s immediate impact on the students.

The third screening was conducted three months after the intervention, in January 2022 (t3). During this phase, the students took the LGVT reading test once more to monitor any long-term improvements in their reading skills. This final screening aimed to evaluate the lasting impact of the intervention on students’ reading abilities and self-efficacy.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for reading competence across two student groups, the control group (CG) and the intervention group (IG), measured at three different time points (t1, t2, and t3). For each group and time point, the table includes the number of participants (N), minimum and maximum scores, mean value (M), and standard deviation (SD).

The reading scores in the control group (CG) show the following findings: In the pre-test (t1), the reading scores of the 39 participants ranged from 37.00 to 70.67, with a mean of 49.84 and a standard deviation of 8.51. The scores were mainly distributed within the “lower middle range” and “upper middle range”. In the post-test (t2), the scores ranged from 30.67 to 72.67, with a slight decrease in the mean to 48.92 and an increase in the standard deviation to 9.13. This suggests a slightly more variable performance across participants. In the follow-up (t3), the number of participants dropped to 36, with scores ranging from 39.33 to 69.67. The mean increased to 52.56, and the standard deviation decreased to 7.13, indicating more consistent performances and a shift toward better scores in the upper middle range (see Table 1).

The reading scores in the intervention group (IG) show the following findings: In t1, the scores of the 14 participants ranged from 35.67 to 62.33, with a mean of 50.31 and a standard deviation of 7.43. The scores spanned the “below average” to “upper middle range” categories, with a generally consistent spread (see Table 1). In t2, the score range was from 35.00 to 66.67, with a mean of 46.95 and a higher standard deviation of 9.59. This indicates a broader spread of scores compared with t1, with some participants improving, while others showed a drop in performance. In t3, the scores of the 13 participants ranged from 41.33 to 65.67, with the mean increasing to 52.18 and the standard deviation decreasing to 7.08. This reflects a more consistent performance and a shift toward higher scores, which were mainly within the “middle range” and “above average” categories.

Over time, both groups showed fluctuations in their mean reading competence. Notably, the IG started with a slightly higher average score at t1, experienced a dip at t2, and then saw improvement by t3, surpassing their initial mean. The CG followed a similar trend, ending with a higher mean at t3 than at t1. The variability in scores (as reflected in the standard deviations) also changed over time, indicating differences in consistency among participants’ performance.

The mixed ANOVA reveals a significant main effect of time on reading competence, with a p-value of 0.02 (F(2, 46) = 4.33), indicating a statistically significant change across the three measurements: Reading Competence_1 (M = 50.54, SD = 8.37), Reading Competence_2 (M = 49.81, SD = 8.94), and Reading Competence_3 (M = 52.46, SD = 7.05). The partial eta squared value of 0.16 suggests a moderate effect size. However, the interaction effect between time and project participant is not significant (p = 0.70, F(2, 46) = 0.36), indicating that the differences in reading gains did not vary significantly between the groups (intervention and control) across the time points. The profile plot shows that while both groups improved over time, the intervention group (M = 50.51, SD = 7.68 for Reading Competence_1, M = 47.87, SD = 9.32 for Reading Competency_2, and M = 52.18, SD = 7.08 for Reading Competency_3) appeared to have a more pronounced improvement post-intervention. Overall, while reading gains were significant over time, the intervention did not result in significantly different outcomes compared to the control group (M = 50.54, SD = 8.37 for Reading Competence_1, M = 49.81, SD = 8.94 for Reading Competence_2, and M = 52.46, SD = 7.05).

These comparisons illustrate (see Figure 3) the general improvement in both the intervention and control groups over time, with the intervention group showing higher performance in the final test. However, the t-tests revealed no statistically significant differences for any test measurement between the groups. It is also evident that the variation in performance (see t1) was reduced in both groups, particularly in the intervention group.

To sum up, the data on the participating students indicate a slight improvement in reading competence for both the intervention and control groups. Notably, the intervention group showed a narrowing of the gap between the minimum and maximum reading scores, suggesting greater consistency in skill levels within the group. However, no statistically significant results were observed from the collected data.

5.3.2. Field Observations of Group Dynamics and Student Engagement in the Theatre Project by the University Trainer

The field observations that were selected and content analysed (Mayring, 2010) by the university trainer in the intervention group throughout the theatre project revealed a highly engaged and supportive group dynamic among the students. According to the trainer, “All the other students felt very comfortable in their roles” (Trainer).

Shortly after rehearsals began, the group independently decided to move forward with a performance, demonstrating initiative and collective motivation: “As there was unanimous interest in participating, the students agreed to perform the play twice—once in front of their classmates in the morning, and again for their parents in the afternoon” (Trainer).

Throughout the exercise phase (reading and performing), students were observed to be interacting in a respectful, appreciative, and constructive manner. They regularly exchanged feedback, supported one another in reading and performing, and remained open to criticism and suggestions. The atmosphere was consistently characterised by mutual encouragement and positive reinforcement, both among the students and between students and trainers.

In a broader context, the attitudes of the group mirrored those that were observed in cycle 1 of the project. Initial reactions included curiosity and excitement about the play itself, coupled with some hesitation regarding the final performance. To address this, the performance was presented as an option rather than a requirement, allowing students to participate without undue pressure.

This approach appeared to foster intrinsic motivation, as the students quickly became eager to immerse themselves in the process. Despite initial reservations, they eventually performed with enthusiasm and confidence—this included singing two songs from the play, which, according to the students, often lingered in their minds as catchy tunes.

Importantly, even students who initially struggled with the reading material (the drama) benefited from the extended duration of the project, which allowed for targeted, individualised support. These students were not marginalised; instead, they observed and learned from their peers. The classroom climate promoted encouragement rather than ridicule, ensuring that all participants felt safe to take risks and grow within the theatrical framework.

From a qualitative perspective, the field observations of the theatre project indicated a marked improvement in group cohesion as a result of the scenic play. The students formed new friendships and reported a strong sense of inclusion throughout the project. No student reported feeling excluded or uncomfortable during the process.

5.3.3. Conclusion of Cycle 2

Overall, these observations underscore the educational value of the scenic play format—not only in promoting literacy and performance skills but also in fostering social–emotional development and a collaborative learning environment.

While the quantitative results in cycle 2 pointed to only modest gains in reading literacy—particularly in reading speed, comprehension, and accuracy—the qualitative data revealed significant educational and socio-emotional benefits. Students who were involved in the theatre project consistently demonstrated strong text comprehension, reflective thinking, intrinsic motivation, and active participation in both rehearsals and the final performance.

Although the students’ initial reactions to the idea of a public performance were characterised by hesitation, their attitudes evolved positively over the course of the project. This shift underscores the value of performative engagement with texts, which not only supported the development of theatrical skills but also fostered meaningful social interaction. By the conclusion of the project, nearly all participants perceived themselves as equal members of the group, with a clearly enhanced sense of group identity and cohesion resulting from the collaborative performance experience.

In relation to the three hypotheses, for cycle 2, it can be assumed that the reading skills (reading speed, comprehension, accuracy) of the participating students at the beginning (t1) were in the middle range, but with a wide distribution—from below to above average. This wide variation in reading performance highlights the need for an effective reading approach that addresses both high-performing and low-performing readers.

By the end of the project, improvements could be observed in both the intervention and control groups, but the gains were more pronounced in the intervention group, particularly among the lowest-performing readers. Their performance shifted from below average to the lower middle range. However, this only represents a small increase and does not indicate statistically significant differences. Therefore, the second hypothesis could not be confirmed based on clear findings.

The third hypothesis, however, can be confirmed. In cycle 2, students in the intervention group demonstrated a high level of social interaction. They discussed their scenes, supported one another in reading and performing, and collaboratively planned both performances for one day. This strong cooperation highlights the social and collaborative benefits of the theatre-based approach.

6. Conclusions

In Cycle 0, only the author’s field notes were collected and analysed (Mayring, 2010), with no additional data from research colleagues. Based on this exploratory case study, three hypotheses were tentatively confirmed: (H1) scenic play addresses dimensions of reading competence, (H2) reading skills can be promoted through production-oriented literature teaching and individualised scaffolding, and (H3) social interaction improved as scenic play became a shared learning goal in the inclusive classroom.

Cycle 1 showed that reading competence dimensions were positively addressed through scenic play; although, without a control group, only exploratory conclusions could be drawn (H1). Specific strategies like paired reading, reading aloud, and choral reading effectively supported reading skills (H2). Additionally, the theatre project significantly enhanced social interaction, leading to new and lasting friendships among participants (H3).

In Cycle 2, students’ initial reading skills varied widely, ranging from below to above average, underscoring the need for differentiated reading approaches. While both intervention and control groups showed improvements, gains were more notable in the intervention group, especially among the lowest-performing readers; however, these gains were modest and not statistically significant; so, the second hypothesis could not be clearly confirmed. The third hypothesis was confirmed, as the intervention group displayed strong social interaction, collaboration, and mutual support during the theatre project, highlighting the social benefits of the approach.

Linked to the three research questions (see Section 3), the findings of this study from cycles 0 to 2 underscore the importance of targeted and inclusive educational interventions in supporting students with special educational needs (SENs) in reading. Although the initial results only indicate slight overall improvements in some parts of reading competence, as measured by means of standardised reading tests at the reading process level (see Section 2), a notable reduction in performance heterogeneity suggests a positive shift toward greater equity among learners.

When students perform, collaborative work through social interaction increases, and this is also possible in an inclusive learning context (Cardol et al., 2025; Polido et al., 2025; Jónsdóttir & Thorkelsdóttir, 2024; Rathje et al., 2021; Boal, 2019; Domkowsky, 2011; Iser, 1978).

In the theatre intervention, all three reading levels were addressed for the participants (see Figure 2). Students received personalised reading support and demonstrated substantial gains in reading fluency, prosody, and accuracy, highlighting the effectiveness of differentiated instruction (see Section 2 and Section 5).

At the process level, students advanced their reading competence by developing local and global coherence, recognising superstructures, and applying the required reading strategies to rehearse scenes meaningfully. This became especially evident when the students began acting on stage—positioning themselves, moving around, and transforming text into action. Such performative engagement required more than surface-level decoding; it demanded deep comprehension and scene-based coordination within the group.

At the subject level, this embodied approach fostered motivation, active participation, and a strengthened self-concept as readers and performers. The students were empowered not only to interpret the text but to co-construct it creatively, bridging literacy with identity.

On the social level, the collaborative nature of theatre—resolving questions such as “who stands where and when”—created opportunities for peer communication and feedback. When performances were shared with parents, educators, classmates, and guests, the project extended beyond the classroom and contributed to a broader school culture. In this way, reading drama texts through performance became a culturally enriching and academically grounded practice that connected individual readers with performers on stage (Boyask et al., 2024; Webber et al., 2024; Rosebrock & Nix, 2020; Denk & Möbius, 2017).

Therefore, reading and performing drama should also be included in the assessment. A standardised reading test does not seem to be suitable for capturing all three levels of reading (see Table 1).

The limitations of this study are the following: All three cycles represent case studies; therefore, the findings have a more exploratory character. No inter-observer checks were conducted during the drama lesson observations. Personal data from participants and their family members would enhance the social dimension of reading development. The reading tests used do not cover the entire reading process level or the other two reading levels (see Figure 2).

The final limitation could explain why we do not see significant increases within the intervention group. The standardised LGVT reading test does not cover all facets of reading competence, and in the study, there are no assessments for reading aloud or prosodic reading.

Looking ahead, qualitative research is needed to examine the long-term effects and transferability of this reading intervention across various educational contexts and countries. Expanding the scope of future studies to include students, the observation of long-term learning processes of individual learners, interviews, or videographic documentation during the intervention sessions would provide deeper insights into how individualised reading instructions—from text to stage—and collaborative teaching can be implemented sustainably, contributing to more equitable and inclusive learning environments.

Further research should explore how this theatre-based literacy intervention can be adapted to diverse educational contexts and cultural settings. Investigating its applicability in various countries, school systems, and among different student populations will be crucial. This includes adapting interventions for different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, students with diverse learning abilities and needs, and/or varied socio-economic contexts. Such work will ensure that the benefits of embodied, collaborative literacy practices are accessible to a broader and more diverse range of learners.

Additionally, future research should investigate the long-term effects and transferability of theatre-based reading interventions. Qualitative studies are needed to observe the sustained development of individual learners over time. Recommended future research directions should include longitudinal observation of students’ literacy development, interviews with students, teachers, and parents to gain deeper insights into learning processes, and/or videographic documentation of intervention sessions to capture the dynamic nature of learning through drama. Expanding the scope of inquiry will help clarify how individualised reading instruction—linking text work with performance—and collaborative teaching models can be implemented sustainably, ultimately contributing to more equitable and inclusive education.

In classroom practice, the theatre intervention successfully addressed all three reading levels—process, subject, and social. Students received personalised support and demonstrated substantial gains in reading fluency, prosody, and comprehension. Through scenic play, they advanced their ability to create local and global coherence, recognise superstructures, and meaningfully apply reading strategies. Acting out scenes required not just decoding but deep comprehension and group coordination, linking literacy with embodied learning.

Collaboration between general and special education teachers was crucial to the project’s success. The study’s use of a Design-Based Research (DBR) approach emphasised the iterative development and testing of educational practices in real classrooms. This not only facilitated pedagogical innovation but also demonstrated how research and practice can be linked sustainably, offering a pathway to broader implementation of inclusive teaching strategies.

For policy, the findings suggest that assessment practices should be expanded to include embodied and performative reading activities, as standardised reading tests alone do not fully capture all facets of reading competence. Policies that promote interdisciplinary teaching and arts integration could enhance inclusive education practices at scale.

Funding

This research was funded by the Potsdam Graduate School at the University of Potsdam, The grants received the author for the years 2021 and 2022 (2021/Giera, 2022/Giera).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines outlined by the University of Potsdam’s ethics committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and confidentiality was maintained throughout the study. Ethic Commission University of Potsdam (Link: https://www.uni-potsdam.de/de/senat/kommissionen-des-senats/ek), Approval Code: 54/2021 (Name: “Stopp Mobbing! Ein Theaterprojekt”, Responsibility: Prof. Dr. Winnie-Karen Giera), Approval Date: 5 October 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Also, written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Berkeley, S., Bender, W. N., Peaster, L. G., & Saunders, L. (2009). Implementation of response to intervention: A snapshot of progress. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(1), 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boal, A. (2019). Theatre of the oppressed (Rev. ed.). Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2002). Index for inclusion: Developing learning and participation in schools. Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education (CSIE). [Google Scholar]

- Boyask, R., Jackson, J., Milne, J., Harrington, C., & May, R. (2024). We enjoy doing reading together: Finding potential in affective encounters with people and things for sustaining volitional reading. Language and Education, 38(4), 578–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardol, M., Nijkamp, J., van Huijzen, S., Meyer, H., & Bussmann, M. (2025). Inclusive theatre with actors with and without intellectual disabilities: An artistic and collaborative challenge with socio-political ambitions. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 30(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremin, T., & Scholes, L. (2024). Reading for pleasure: Scrutinising the evidence base—Benefits, tensions and recommendations. Language and Education, 38(4), 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denk, R., & Möbius, T. (2017). Dramen und theaterdidaktik (3rd ed.). Erich Schmidt Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2000). Handbook of qualitative research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Domkowsky, R. (2011). Theaterspielen—Und seine Wirkungen [Doctoral dissertation, Universität der Künste]. OPUS. Available online: https://www.fachportal-paedagogik.de/literatur/vollanzeige.html?FId=3137761 (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Fischer, S. M., Bilz, L., & HBSC Study Group Germany. (2024). Traditional bullying and cyberbullying at schools in Germany: Results of the HBSC study 2022 and trends from 2009/10 to 2022. Journal of Health Monitoring, 9(1), 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, D. S., & Welsh, D. (2024). A mixed-method case study of readers’ theatre with African immigrant and refugee students. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 30(1), 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giera, W.-K. (2024). Reading combined with theatre playing. ELINET. Available online: https://elinet.pro/reading-combined-with-theatre-playing/ (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Giera, W.-K., Böhme, K., & Widmann, I. (2024). Lernangebote inklusiv gestalten und reflektieren—Aber wie? Das Potsdamer Inklusionsdidaktische Unterrichtsmodell im Praxistest: Bericht zum Workshop auf dem 57. bak-Seminartag 2023 an der Universität Potsdam. SEMINAR, 30(1), 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, A. (2015). Unterrichtsqualität und lehrerprofessionalität: Diagnose, evaluation und verbesserung des unterrichts (6. Aufl.). Kallmeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Iser, W. (1978). The act of reading: A theory of aesthetic response. Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jónsdóttir, J. G., & Thorkelsdóttir, R. B. (2024). “It really connects all participants” example of a playbuilding process through youth theatre-based competition in Iceland. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 30(1), 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounin, J. S. (2006). Techniken der Klassenführung (M. Gellert & C. Gellert, Übers.). Waxmann. Original work published 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfe, C. (2013). Allein! Tatort Schule. Theaterstücke online. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. (2010). Qualitative inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und techniken [Qualitative content analysis: Basics and techniques]. Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2015). PISA 2015 results (volume III): Students’ well-being. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2017). How much of a problem is bullying at school? In PISA in Focus, 74. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 results (volume I): What students know and can do. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippakos, Z. A., Howell, E., & Pellegrino, A. (Eds.). (2021). Design-based research in education: Theory and applications. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polido, A., Ehnert, F., Jossin, J., & Mascarenhas, A. (2025). Theatre of the Innova(c)tors: An interactive theatre tool to create transformative spaces. Sustainability Science, 20, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathje, S., Hackel, L., & Zaki, J. (2021). Attending live theatre improvesempathy, changes attitudes, and leads to pro-social behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 95, 104–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosebrock, C., & Nix, D. (2020). Grundlagen der lesedidaktik und der systematischen schulischen leseförderung (9. Aufl.). Schneider. [Google Scholar]

- Schmalenbach, C., Giera, W.-K., Kayser, D. N., & Plöger, S. (2024). Implementing CI in Germany—Relevant principles, contextual considerations, and first steps. Intercultural Education, 36, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W., Schlagmüller, M., & Ennemoser, M. (2017). LGVT 5-12 +: Lesegeschwindigkeits-und–Verständnistest für die klassen 5–12 (2nd ed.). Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Sokari, I. F. (2025). Audience engagement: Analyzing the impact of feedback on theatre and film productions. Research Journal of Education, 44–48. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389634139 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2025). Glossary literacy. Available online: https://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/literacy (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities and optional protocol. Available online: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds. & Trans.). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, C., Santi, E., Calabrese, J., & McGeown, S. (2024). Using participatory approaches with children and young people to research volitional reading. Language and Education, 38(4), 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).