Association of High Levels of Bullying and Cyberbullying with Study Time Management and Effort Self-Regulation in Adolescent Boys and Girls

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variables: Resource Management Learning Strategies

2.2.2. Predictor/Independent Variables: Bullying and Cyberbullying

2.2.3. Confounding Variables

- Age and Maternal Education Level

- Body Mass Index (BMI) and Weekly Physical Activity Level

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

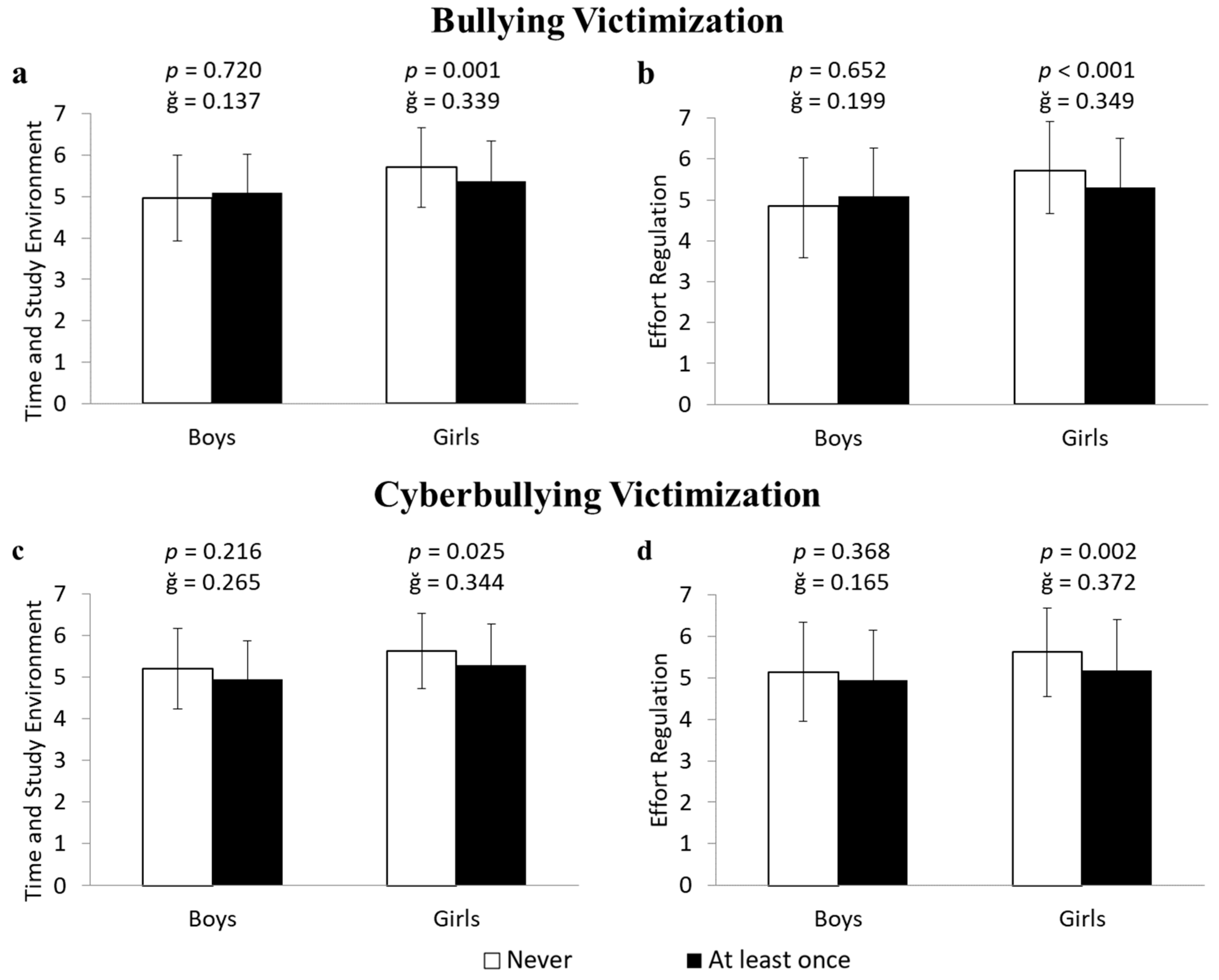

3.1. Analysis of Covariance for Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization in Relation to Resource Management Learning Strategies

3.2. Analysis of Covariance for Bullying and Cyberbullying Aggression in Relation to Resource Management Learning Strategies

3.3. Binary Logistic Regression Analyses of Bullying and Cyberbullying in Relation to Study Time Management and Effort Regulation

4. Discussion

4.1. Associations and Risk of Being a Victim of Bullying and Cyberbullying

4.2. Associations and Risk of Being a Bullying and Cyberbullying Aggressor

4.3. Recommendations for Combating Bullying and Cyberbullying and Strengthening Resource Management Strategies for Learning

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, S. I., & Shahbuddin, N. B. (2022). The relationship between cyberbullying and mental health among university students. Sustainability, 14(11), 6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparisi, D., Delgado, B., Bo, R. M., & Martínez-Monteagudo, M. C. (2021). Relationship between cyberbullying, motivation and learning strategies, academic performance, and the ability to adapt to university. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, P., & Lord, R. N. (2021). The impact of physically active learning during the school day on children’s physical activity levels, time on task and learning behaviours and academic outcomes. Health Education Research, 36(3), 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baharvand, P., Nejad, E. B., Karami, K., & Amraei, M. (2021). A review study of the role of socioeconomic status and its components in children’s health. Global Journal of Medical, Pharmaceutical, and Biomedical Update, 16(9), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S., Garg, N., Singh, J., & Van Der Walt, F. (2024). Cyberbullying and mental health: Past, present and future. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1279234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C., & Sacau-Fontenla, A. (2021). New insights on the mediating role of emotional intelligence and social support on university students’ mental health during covid-19 pandemic: Gender matters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 12935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozyiğit, A., Utku, S., & Nasibov, E. (2021). Cyberbullying detection: Utilizing social media features. Expert Systems with Applications, 179, 115001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G., & Kerslake, J. (2015). Cyberbullying, self-esteem, empathy and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M., Branquinho, C., & de Matos, M. G. (2021). Cyberbullying and bullying: Impact on psychological symptoms and well-being. Child Indicators Research, 14(1), 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L., Xue, J., & Han, Z. (2020). School bullying victimization and self-rated health and life satisfaction: The gendered buffering effect of educational expectations. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R., Casas, J. A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., Thompson, F., Barkoukis, V., Tsorbatzoudis, H., Brighi, A., Guarini, A., Pyzalski, J., & Plichta, P. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, J. H., Oostdam, R., & Voogt, J. (2021). Self-regulation strategies in blended learning environments in higher education: A systematic review. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(6), 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Asam, A., & Samara, M. (2016). Cyberbullying and the law: A review of psychological and legal challenges. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zaatari, W., & Maalouf, I. (2022). How the bronfenbrenner bio-ecological system theory explains the development of students’ sense of belonging to school? SAGE Open, 12(4), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, F. A., López, I. L. d. L. G., & Benavides, A. D. (2023). Emotional impact of bullying and cyber bullying: Perceptions and effects on students. Revista Caribeña de Ciencias Sociales, 12(1), 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C. B. R., Smokowski, P. R., Rose, R. A., Mercado, M. C., & Marshall, K. J. (2019). Cumulative bullying experiences, adolescent behavioral and mental health, and academic achievement: An integrative model of perpetration, victimization, and bystander behavior. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(9), 2415–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyuboglu, M., Eyuboglu, D., Pala, S. C., Oktar, D., Demirtas, Z., Arslantas, D., & Unsal, A. (2021). Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying: Prevalence, the effect on mental health problems and self-harm behavior. Psychiatry Research, 297, 113730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijóo, S., O’Higgins-Normanb, J., Foodyb, M., Pichela, R., Brañaa, T., Varelaa, J., & Rial, A. (2022). Sex differences in adolescent bullying behaviours. Psychosocial Intervention, 30(2), 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A. M., Martins, M. C., Farinha, M., Silva, B., Ferreira, E., Caldas, A. C., & Brandão, T. (2020). Bullying’s negative effect on academic achievement. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 9(3), 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H., Tong, F., Wang, Z., Tang, S., Yoon, M., Ying, M., & Yu, X. (2021). Examining self-regulated learning strategy model: A measurement invariance analysis of mslq-cal among college students in China. Sustainability, 13(18), 10133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellström, L., & Beckman, L. (2020). Adolescents’ perception of gender differences in bullying. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(1), 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosozawa, M., Bann, D., Fink, E., Elsden, E., Baba, S., Iso, H., & Patalay, P. (2021). Bullying victimisation in adolescence: Prevalence and inequalities by gender, socioeconomic status and academic performance across 71 countries. EClinicalMedicine, 41, 101142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. (2020). Exploring the relationship between school bullying and academic performance: The mediating role of students’ sense of belonging at school. Educational Studies, 48(2), 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D. B., Vaughn, M. G., & Kremer, K. P. (2019). Bully victimization and child and adolescent health: New evidence from the 2016 NSCH. Annals of Epidemiology, 29, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaskulska, S., Jankowiak, B., Pérez-Martínez, V., Pyżalski, J., Sanz-Barbero, B., Bowes, N., Claire, K. D., Neves, S., Topa, J., Silva, E., Mocanu, V., Gena Dascalu, C., & Vives-Cases, C. (2022). Bullying and cyberbullying victimization and associated factors among adolescents in six European countries. Sustainability, 14(21), 14063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilcec, R. F., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., & Maldonado, J. J. (2017). Self-regulated learning strategies predict learner behavior and goal attainment in Massive Open Online Courses. Computers and Education, 104, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R. M., & Limber, S. P. (2013). Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, S13–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S., Welch, S., & Mason, M. (2020). Physical education environment and student physical activity levels in low-income communities. BMC Public Health, 20, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiner, M., Dwivedi, A. K., Villanos, M. T., Singh, N., Blunk, D., & Peinado, J. (2014). Psychosocial profile of bullies, victims, and bully-victims: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 2, 001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Menestrel, S. (2020). Preventing bullying: Consequences, prevention, and intervention. Journal of Youth Development, 15(3), 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepinet, U., Tanniou, J., Communier, E. C., Créach, V., & Beaumont, M. (2023). Impact of anthropometric data and physical activity level on the closed kinetic chain upper extremity stability test (CKCUEST) score: A cross-sectional study. Physical Therapy in Sport, 64, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C., Wang, P., Martin-Moratinos, M., Bella-Fernández, M., & Blasco-Fontecilla, H. (2022). Traditional bullying and cyberbullying in the digital age and its associated mental health problems in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 2895–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D., Wang, D., Zou, J., Li, C., Qian, H., Yan, J., & He, Y. (2023). Effect of physical activity interventions on children’s academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Pediatrics, 182(8), 3587–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-López, E. J., De La Torre-Cruz, M., Suarez-Manzano, S., & Ruiz-Ariza, A. (2018). Analysis of the effect size of overweight in muscular strength tests among adolescents: Reference values according to sex, age, and body mass index. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 32(5), 1404–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, L. T., Simcock, G., Schwenn, P., Beaudequin, D., Driver, C., Kannis-Dymand, L., Lagopoulos, J., & Hermens, D. F. (2022). Cyberbullying, metacognition, and quality of life: Preliminary findings from the Longitudinal Adolescent Brain Study (LABS). Discover Psychology, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menken, M. S., Isaiah, A., Liang, H., Rivera, P. R., Cloak, C. C., Reeves, G., Lever, N. A., & Chang, L. (2022). Peer victimization (bullying) on mental health, behavioral problems, cognition, and academic performance in preadolescent children in the ABCD Study. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 925727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez-Fadda, S. M., Castro-Castañeda, R., Vargas-Jiménez, E., Musitu-Ochoa, G., & Callejas-Jerónimo, J. E. (2022). Impact of bullying—Victimization and gender over psychological distress, suicidal ideation, and family functioning of Mexican adolescents. Children, 9(5), 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregón-Cuesta, A. I., Mínguez-Mínguez, L. A., León-del-Barco, B., Mendo-Lázaro, S., Fernández-Solana, J., González-Bernal, J. J., & González-Santos, J. (2022). Bullying in adolescents: Differences between gender and school year and relationship with academic performance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, T., Olseth, A., Sørlie, M. A., & Hukkelberg, S. (2023). Teacher’s assessment of gender differences in school performance, social skills, and externalizing behavior from fourth through seventh grade. Journal of Education, 203(1), 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ruiz, R., Del Rey, R., & Casas, J. A. (2016). Evaluar el bullying y el cyberbullying validación española del EBIP-Q y del ECIP-Q. Psicologia Educativa, 22(1), 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciello, M., Corbelli, G., Di Pomponio, I., & Cerniglia, L. (2023). Protective role of self-regulatory efficacy: A moderated mediation model on the influence of impulsivity on cyberbullying through moral disengagement. Children, 10(2), 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peled, Y. (2019). Cyberbullying and its influence on academic, social, and emotional development of undergraduate students. Heliyon, 5(3), e01393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Neto, A., & Barbosa, L. (2019). Bullying and cyberbullying: Conceptual controversy in Brazil. In A. Pereira Neto, & M. Flynn (Eds.), The internet and health in Brazil. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrigna, L., Thomas, E., Brusa, J., Rizzo, F., Scardina, A., Galassi, C., Lo Verde, D., Caramazza, G., & Bellafiore, M. (2022). Does learning through movement improve academic performance in primary schoolchildren? A systematic review. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 10, 841582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintrich, P., Smith, D., Duncan, T., & Mckeachie, W. (1991). A manual for the use of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ). University of Michigan. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED338122 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Prochaska, J. J., Sallis, J. F., & Long, B. (2001). A physical activity screening measure for use with adolescents in primary care. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 155(5), 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przybylski, A. K., & Bowes, L. (2017). Cyberbullying and adolescent well-being in England: A population-based cross-sectional study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 1(1), 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, C. F., Cascallar, E., & Kyndt, E. (2020). Socio-economic status and academic performance in higher education: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 29, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffing, S., Wach, F. S., Spinath, F. M., Brünken, R., & Karbach, J. (2015). Learning strategies and general cognitive ability as predictors of gender- specific academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seum, T., Meyrose, A. K., Rabel, M., Schienkiewitz, A., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2022). Pathways of parental education on children’s and adolescent’s body mass index: The mediating roles of behavioral and psychological factors. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 763789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentepohl, S., Waldeyer, J., Fleischer, J., Roelle, J., Leutner, D., & Wirth, J. (2022). How did it get so late so soon? The effects of time management knowledge and practice on students’ time management skills and academic performance. Sustainability, 14(9), 5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urruticoechea, A., Oliveri, A., Vernazza, E., Giménez-Dasí, M., Martínez-Arias, R., & Martín-Babarro, J. (2021). The relative age effects in educational development: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 8966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, M., Hatamzadeh, N., Zinat Motlagh, F., Rahimi, H., & Khalvandi, M. (2018). The relationship between resource management learning strategies and academic achievement. International Journal of Health and Life Sciences, 4(1), e79607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, A. S. (2021). Estrategias de aprendizaje de estudiantes universitarios como predictores de su rendimiento académico. Revista Complutense de Educación, 32(2), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., & Yu, Z. (2023). Gender-moderated effects of academic self-concept on achievement, motivation, performance, and self-efficacy: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 11361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waseem, M., & Nickerson, A. B. (2023). Identifying and addressing bullying. National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441930/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Weinreich, L., Haberstroh, S., Schulte-Körne, G., & Moll, K. (2023). The relationship between bullying, learning disorders and psychiatric comorbidity. BMC Psychiatry, 23, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, F., Liu, M., & Liu, T. (2023). The role of coping styles in mediating the dark triad and bullying: An analysis of gender difference. Behavioral Sciences, 13(7), 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C., Huang, S., Evans, R., & Zhang, W. (2021). Cyberbullying among adolescents and children: A comprehensive review of the global situation, risk factors, and preventive measures. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 634909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All (n = 1330) | Boys (n = 651) | Girls (n = 679) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | SD/% | Mean | SD/% | Mean | SD/% | p | |

| Age (years) | 13.22 | 1.75 | 13.22 | 1.787 | 13.22 | 1.72 | 0.965 | |

| Weight (kg) | 52.31 | 13.40 | 54.65 | 14.81 | 50.06 | 11.44 | <0.001 | |

| Height (m) | 1.59 | 0.11 | 1.61 | 0.13 | 1.57 | 0.08 | <0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.47 | 3.97 | 20.70 | 3.91 | 20.25 | 4.03 | 0.037 | |

| Maternal Education Level (%) | No education | 64 | 4.8% | 32 | 5.0% | 32 | 4.7% | <0.001 |

| Primary | 136 | 10.2% | 68 | 10.6% | 68 | 10.0% | ||

| Secondary | 188 | 14.1% | 70 | 11.0% | 118 | 17.4% | ||

| Professional training | 174 | 13.1% | 84 | 13.1% | 90 | 13.3% | ||

| University | 487 | 36.6% | 226 | 35.5% | 261 | 38.4% | ||

| Do not know | 269 | 20.2% | 159 | 24.9% | 110 | 16.2% | ||

| Weekly Physical Activity (average) | 4.01 | 1.76 | 4.30 | 1.81 | 3.73 | 1.67 | <0.001 | |

| Academic performance | 6.89 | 1.55 | 6.76 | 1.53 | 7.02 | 1.55 | 0.007 | |

| Bullying Victimization | Never | 198 | 14.9% | 112 | 17.2% | 86 | 12.7% | 0.085 |

| Occasionally | 703 | 52.9% | 327 | 50.2% | 376 | 55.4% | ||

| Once or twice/month | 322 | 24.2% | 156 | 24.0% | 166 | 24.4% | ||

| Once/week | 83 | 6.2% | 46 | 7.1% | 37 | 5.4% | ||

| More than once/week | 24 | 1.8% | 10 | 1.5% | 14 | 2.1% | ||

| Bullying Aggression | Never | 362 | 27.2% | 162 | 24.9% | 200 | 29.5% | 0.007 |

| Occasionally | 767 | 57.7% | 371 | 57.0% | 396 | 58.3% | ||

| Once or twice/month | 156 | 11.7% | 93 | 14.3% | 63 | 9.3% | ||

| Once/week | 37 | 2.8% | 23 | 3.5% | 14 | 2.1% | ||

| More than once/week | 8 | 0.6% | 2 | 0.3% | 6 | 0.9% | ||

| Cyberbullying Victimization | Never | 582 | 43.8% | 304 | 46.7% | 278 | 40.9% | 0.101 |

| Occasionally | 664 | 49.9% | 311 | 47.8% | 353 | 52.0% | ||

| Once or twice/month | 61 | 4.6% | 26 | 4.0% | 35 | 5.2% | ||

| Once/week | 21 | 1.6% | 8 | 1.2% | 13 | 1.9% | ||

| More than once/week | 2 | 0.2% | 2 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Cyberbullying Aggression | Never | 755 | 56.8% | 363 | 55.8% | 392 | 57.7% | 0.368 |

| Occasionally | 515 | 38.7% | 255 | 39.2% | 260 | 38.3% | ||

| Once or twice/month | 37 | 2.8% | 23 | 3.5% | 14 | 2.1% | ||

| Once/week | 23 | 1.7% | 10 | 1.5% | 13 | 1.9% | ||

| More than once/week | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Resource Management Strategies | Time and Study Environment | 5.25 | 0.97 | 5.07 | 0.94 | 5.41 | 0.97 | <0.001 |

| Effort Regulation | 5.19 | 1.20 | 5.01 | 1.20 | 5.36 | 1.19 | <0.001 | |

| Boys (602) | Girls (649) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bullying Victimization | N | p | OR | 95%CI | N | p | OR | 95%CI | |

| Time and Study Environment | High | 242 | 1 | Referent | 378 | 1 | Referent | ||

| Low | 360 | 0.332 | 1.152 | 0.710–1.553 | 271 | <0.001 | 3.119 | 1.983–6.425 | |

| Effort Regulation | High | 243 | 1 | Referent | 366 | 1 | Referent | ||

| Low | 359 | 0.043 | 1.440 | 1.044–1.811 | 283 | <0.001 | 4.202 | 2.025–7.488 | |

| Cyberbullying Victimization | |||||||||

| Time and Study Environment | High | 242 | 1 | Referent | 378 | 1 | Referent | ||

| Low | 360 | 0.225 | 1.229 | 0.923–1.499 | 271 | <0.001 | 2.254 | 1.476–3.442 | |

| Effort Regulation | High | 243 | 1 | Referent | 366 | 1 | Referent | ||

| Low | 359 | 0.119 | 1.322 | 0.802–2.036 | 283 | <0.001 | 3.216 | 2.039–5.071 | |

| Boys (602) | Girls (649) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bullying Aggression | N | p | OR | 95%CI | N | p | OR | 95%CI | |

| Time and Study Environment | High | 242 | 1 | Referent | 378 | 1 | Referent | ||

| Low | 360 | 0.106 | 1.166 | 1.253–2.806 | 271 | <0.001 | 2.765 | 1.823–3.411 | |

| Effort Regulation | High | 243 | 1 | Referent | 366 | 1 | Referent | ||

| Low | 359 | 0.045 | 1.963 | 1.416–2.722 | 283 | <0.001 | 2.342 | 1.698–3.230 | |

| Cyberbullying Aggression | |||||||||

| Time and Study Environment | High | 242 | 1 | Referent | 378 | 1 | Referent | ||

| Low | 360 | <0.001 | 6.219 | 2.927–11.752 | 271 | 0.115 | 1.333 | 0.954–2.139 | |

| Effort Regulation | High | 243 | 1 | Referent | 366 | 1 | Referent | ||

| Low | 359 | <0.001 | 4.362 | 2.616–9.555 | 283 | 0.005 | 3.311 | 1.533–6.836 | |

| Boys | Girls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Differences | Risk | Mean Differences | Risk | ||

| Victims | Bullying | N/A | ×1.4 Effort regulation | −5.9% Time and study environment management −7.7% Effort regulation | ×3.1 Time and study environment management ×4.2 Effort regulation |

| Cyberbullying | N/A | N/A | −6.2% Time and study environment management −8.3% Effort regulation | ×2.3 Time and study environment management ×3.2 Effort regulation | |

| Aggressors | Bullying | −5.8% Time and study environment management | ×2.0 Effort regulation | −8.7% Time and study environment management −10.2% Effort regulation | ×1.8 Time and study environment management ×2.3 Effort regulation |

| Cyberbullying | −9.6% Time and study environment management −8.2% Effort regulation | ×6.2 Time and study environment management ×4.4 Effort regulation | −8.6% Effort regulation | ×3.3 Effort regulation | |

| Interventions to Strengthen Learning Resource Management for Victims | Interventions to Strengthen Learning Resource Management for Aggressors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Students | Bullying | Set achievable daily academic goals to foster self-esteem through small academic victories. Design a classroom program to teach students how to organize their personal study space, emphasizing the importance of maintaining a clean, orderly, and distraction-free environment. Implement mentorship programs with older students or adults to develop perseverance skills. | Guide students to set goals that include commitments to avoid bullying behaviors and replace them with helpful or supportive actions toward others. Design classroom activities aimed at developing empathy and organizing personal space. Introduce a recognition system that values respect for others and academic effort. |

| Cyberbullying | Establish specific digital use schedules that are separate from study times. Teach the use of tools to block harmful content. Create a system that recognizes and rewards their academic efforts, regardless of the final outcome. | Develop workshops to reflect on the impact of their digital interactions, where students analyze how they spend their time online and the effects of their actions on others. Promote self-regulation tools such as blocking extensions to prevent digital distractions. Implement a recognition system that rewards not only academic achievement but also efforts to interact respectfully with others. | |

| Educators | Bullying | Train in time regulation so that teachers can teach students to plan and prioritize tasks, improving organization and helping to reduce the emotional impact of bullying on academic performance. Create a safe study environment through inclusive and supportive classroom strategies that foster a space where victims feel valued and protected. Provide training in positive motivation techniques to reinforce victims’ efforts, even when they face emotional challenges. | Train in techniques of self-control and regulation of effort, providing teachers with strategies to guide students in managing impulses and committing to their studies, promoting behavioral changes. Assign positive roles to aggressors, promoting leadership in collaborative activities. Train teachers in the use of behavioral reinforcement methods to teach aggressors how to maintain consistent academic effort. |

| Cyberbullying | Train teachers in digital time management so they can guide students in organizing their online time, minimizing distractions and exposure to cyberbullying. Train in creating safe digital study environments using content control tools and strategies, creating a protected space that supports concentration and reduces anxiety in victims. Train teachers in socio-emotional learning techniques, such as self-affirmation activities and group exercises that enhance student confidence. | Train teachers in self-reflection techniques on digital time and behavior, enabling them to foster responsible social media use and critical reflection on online interactions among aggressors. Train teachers in respectful digital learning environments, equipping them with tools to teach about respect for others and self-control in digital use. Train educators in behavioral reinforcement methods to teach aggressors how to sustain academic effort. | |

| Family | Bullying | Train parents, guardians, and caregivers in time management so they can help their children structure their home study time by establishing schedules that foster a supportive and organized environment. Train families in creating safe and organized study environments. Teach families techniques to identify signs of demotivation in their children and provide tools to help regulate effort, such as home-based reward systems for academic achievements. | Train in techniques of self-control and recognition of effort for behavioral change, teaching families to guide the setting of goals and self-regulation in studies. Create a home environment of respect and reflection where children can reflect on their behaviors and their impact on others, promoting empathy and self-awareness. Train parents and guardians in self-regulation techniques and recognition of effort to guide their children toward behavior change. |

| Cyberbullying | Teach families to guide the ethical and responsible use of technology, training them to establish device usage schedules and monitor online content. Train families to create a safe digital environment at home through the use of parental control tools and encourage healthy digital device use. Train families to help victims rebuild their confidence and academic effort through the use of achievable goals and consistent support at home. | Train in self-regulation of network use and digital supervision so families can guide the ethical use of technology, promoting self-control and reducing negative online behaviors. Train in fostering a respectful digital environment, teaching parents to conduct reflective exercises on the impact of online interactions, promoting empathy and responsibility. Conduct joint reflection exercises on how irresponsible social media use affects academic and emotional performance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Solas-Martínez, J.L.; Rusillo-Magdaleno, A.; Garrote-Jurado, R.; Ruiz-Ariza, A. Association of High Levels of Bullying and Cyberbullying with Study Time Management and Effort Self-Regulation in Adolescent Boys and Girls. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050563

Solas-Martínez JL, Rusillo-Magdaleno A, Garrote-Jurado R, Ruiz-Ariza A. Association of High Levels of Bullying and Cyberbullying with Study Time Management and Effort Self-Regulation in Adolescent Boys and Girls. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):563. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050563

Chicago/Turabian StyleSolas-Martínez, Jose Luis, Alba Rusillo-Magdaleno, Ramón Garrote-Jurado, and Alberto Ruiz-Ariza. 2025. "Association of High Levels of Bullying and Cyberbullying with Study Time Management and Effort Self-Regulation in Adolescent Boys and Girls" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050563

APA StyleSolas-Martínez, J. L., Rusillo-Magdaleno, A., Garrote-Jurado, R., & Ruiz-Ariza, A. (2025). Association of High Levels of Bullying and Cyberbullying with Study Time Management and Effort Self-Regulation in Adolescent Boys and Girls. Education Sciences, 15(5), 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050563