Gender Differences in Eating Habits, Screen Time, Health-Related Quality of Life and Body Image Perception in Primary and Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Study Variables

2.3.1. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet

2.3.2. Screen Time

2.3.3. Health-Related Quality of Life

2.3.4. Self-Concept of Body Image

2.4. Data Collection Tools

2.4.1. KIDMED Index

2.4.2. Screen Time

2.4.3. Health-Related Quality of Life

2.4.4. Perception of Body Image

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRQOL | Health-related quality of life |

| BSGs | Body Size Guides |

| QOL | Quality of life |

| PA | Physical activity |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ESO | Secondary education |

| SSBQ | Screen-time Sedentary Behaviour Questionnaire |

| HELENA | Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Abd El Aal Thabet Omar, R., Mohamed Magdi Fakhreldin Mohamed, H., Said Abdelhady Garf, F., Mohamed Mahmoud, T., & Mohammed Mahmoud Abu Salem, E. (2021). Correlation between weight and body image among secondary school students. Egyptian Journal of Health Care, 12(2), 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton-Păduraru, D. T., Gotcă, I., Mocanu, V., Popescu, V., Iliescu, M. L., Miftode, E. G., & Boiculese, V. L. (2021). Assessment of eating habits and perceived benefits of physical activity and body attractiveness among adolescents from Northeastern Romania. Applied Sciences, 11(22), 11042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrayás Grajera, M. J., Quiñones, I. T., & Díaz Bento, M. S. (2018). Body image perception by gender and age in adolescents of Huelva. Retos, 34, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación Española de Pediatría. (2024). Actualización del plan digital familiar: Recomendaciones sobre el uso de pantallas en la infancia y adolescencia. Asociación Española de Pediatría. [Google Scholar]

- Aymerich, M., Berra, S., Guillamón, I., Herdman, M., Alonso, J., Ravens-Sieberer, U., & Rajmil, L. (2005). Desarrollo de la versión en español del KIDSCREEN: Un cuestionario de calidad de vida para la población infantil y adolescente. Gaceta Sanitaria, 19(2), 93–102. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0213-91112005000200002&lng=es&tlng=es (accessed on 14 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ávila Francés, M., Sánchez Pérez, M. C., & Bueno Baquero, A. (2022). Factores que facilitan y dificultan la transición de educación primaria a secundaria. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 40(1), 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, T., McLennon, S. M., Carpenter, J. S., Buelow, J. M., Otte, J. L., Hanna, K. M., Ellett, M. L., Hadler, K. A., & Welch, J. L. (2012). Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Haim Erez, A., Kuhle, S., Mcisaac, J.-L., & Weintraub, N. (2020). School quality of life: Cross-national comparison of students’ perspectives. Work, 67, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibiloni, M. D. M., Gallardo-Alfaro, L., Gómez, S. F., Wärnberg, J., Osés-Recalde, M., González-Gross, M., Gusi, N., Aznar, S., Marín-Cascales, E., González-Valeiro, M. A., Serra-Majem, L., Terrados, N., Segu, M., Lassale, C., Homs, C., Benavente-Marín, J. C., Labayen, I., Zapico, A. G., Sánchez-Gómez, J., … Tur, J. A. (2022). 45071 Determinants of adherence to the mediterranean diet in Spanish children and adolescents: The PASOS study. Nutrients, 14(4), 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buja, A., Grotto, G., Brocadello, F., Sperotto, M., & Baldo, V. (2020). Primary school children and nutrition: Lifestyles and behavioral traitsassociated with a poor-to-moderate adherence to the Mediterraneandiet. A cross-sectional study. European Journal of Pediatrics, 179, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantó, E. G., Guillamón, A. R., & Nieto López, L. (2021). Relación entre condición física global, coordinación motriz y calidad de vida percibida en adolescentes españoles. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 24(1), 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, R., Diz, J., Redondo-Gutiérrez, L., & Ayán, C. (2023). Influencia de la actividad en la imagen corporal en preadolescentes y adolescentes: Importancia del índice de masa corporal como factor de confusión. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 40(3), 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Castrillo, P. C., Villarino, M. d. l. Á. F., Reboredo, M. B. T., & González Valeiro, M. Á. (2021). Relations between health perception and physical self-concept in adolescents. The Open Sports Sciences Journal, 13(1), 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesnales, N. I., & Thyer, B. A. (2023). Health-related quality of life measures. In Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K. H., Parrish, A. M., Cliff, D. P., Kemp, B. J., Zhang, Z., & Okely, A. D. (2020). Changes in physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep across the transition from primary to secondary school: A systematic review. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(5), 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M. (2022). Dietary trajectories through the life course: Opportunities and challenges. British Journal of Nutrition, 128(1), 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofaro, D. G. D., De Andrade, S. M., Mesas, A. E., Fernandes, R. A., & Farias Júnior, J. C. (2016). Higher screen time is associated with overweight, poor dietary habits and physical inactivity in Brazilian adolescents, mainly among girls. European Journal of Sport Science, 16(4), 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colás, M., & Castro, N. (2011). Autoimagen corporal de los adolescentes: Investigación desde una perspectiva de género. Universidad de Sevilla. [Google Scholar]

- Cragun, D., Debate, R. D., Ata, R. N., & Thompson, J. K. (2013). Psychometric properties of the body esteem scale for adolescents and adults in an early adolescent sample. Eating and Weight Disorders—Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 18, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, M., Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., Saunders, T., Hamilton, H., Benchimol, E., & Chaput, J.-P. (2020). Combinations of physical activity and screen time recommendations and their association with overweight/obesity in adolescents. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, C., Cachón, J., Zagalaz, M. L., & González González de Mesa, C. (2017). Cómo me veo: Estudio diacrónico de la imagen corporal. Instrumentos de evaluación/How I see myself: Diacronic study of my body image. Evaluation instruments. Magister, 29(1), 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumuid, D., Olds, T., Lewis, L. K., Martin-Fernández, J. A., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Barreira, T., Broyles, S. T., Chaput, J. P., Fogelholm, M., Hu, G., Kuriyan, R., Kurpad, A., Lambert, E. V., Maia, J., Matsudo, V., Onywera, V. O., Sarmiento, O. L., Standage, M., Tremblay, M. S., … Maher, C. (2017). Health-related quality of life and lifestyle behavior clusters in school-aged children from 12 countries. Journal of Pediatrics, 183, 178–183.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enríquez Peralta, R. E., & Quintana Salinas, M. R. (2016). Autopercepción de la imagen corporal y prácticas para corregirla, en adolescentes de una institución educativa, Lima, Perú. Anales de La Facultad de Medicina, 77(2), 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, F., Sanmarchi, F., Marini, S., Masini, A., Scrimaglia, S., Adorno, E., Soldà, G., Arrichiello, F., Ferretti, F., Rangone, M., Celenza, F., Guberti, E., Tiso, D., Toselli, S., Lorenzini, A., Dallolio, L., & Sacchetti, R. (2022). Weekday and weekend differences in eating habits, physical activity and screen time behavior among a sample of primary school children: The “Seven days for my health” project. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteban-Gonzalo, S., Esteban-Gonzalo, L., Cabanas-Sánchez, V., Miret, M., & Veiga, O. L. (2020). The investigation of gender differences in subjective wellbeing in children and adolescents: The up&down study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez Gómez, E. F., & Hoyos Cuartas, L. A. (2021). Caracterización de las actividades de tiempo libre de los adolescentes del municipio del Valle de San José—Santander y las expectativas frente a los programas de actividad física. Revista Digital: Actividad Física y Deporte, 7(1), e1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D., Borriello, G. A., & Field, A. P. (2018). A review of the academic and psychological impact of the transition to secondary education. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2016). Social media and body image concerns: Current research and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Guerrero, M., Suárez Ramíre, M., Feu Molina, S., & Suárez Muñoz, Á. (2019). Nivel de actividad física extraescolar entre el alumnado de educación primaria y secundaria. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 136, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgar, M. I., Rey, C. N., & Lamas, M. F. (2013). La transición de la educación primaria a la educación secundaria: Sugerencias para padres. Innovación Educativa, 23, 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- Franco Arévalo, D., De la Cruz Sánchez, E., & Feu, S. (2023). Evolución de la práctica de actividad física durante la transición de la educación primaria a secundaria obligatoria. Universitas Psychologica, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franic, I., Boljat, P., Hozo, E. R., Burger, A., & Matana, A. (2022). Parental traits associated with adherence to the mediterranean diet in children and adolescents in Croatia: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients, 14(13), 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Dieta Mediterránea. (n.d.). ¿Qué es la dieta mediterránea? Available online: https://dietamediterranea.com/nutricion-saludable-ejercicio-fisico/ (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- García Cabrera, S., Herrera Fernández, N., Rodríguez Hernández, C., Nissensohn, M., Román-Viñas, B., & Serra-Majem, L. (2015). Kidmed test; prevalence of low adherence to the mediterranean diet in children and young; a systematic review. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 32(6), 2390–2399. [Google Scholar]

- Gasol Foundation Europa. (2023). Informe preliminar del estudio PASOS 2022: Resultados principales. Gasol Foundation Europa. Available online: https://gasolfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/GF-PASOS-informe-2022-WEB.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Gillison, F., Standage, M., & Skevington, S. (2008). Changes in quality of life and psychological need satisfaction following the transition to secondary school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(1), 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, M., Tornquist, L., Tornquist, D., & Caputo, E. (2021). Body image is associated with leisure-time physical activity and sedentary behavior in adolescents: Data from the Brazilian National School-based health survey (PeNSE 2015). Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 43, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, S. F., Casas, R., Palomo, V. T., Martin Pujol, A., Fíto, M., & Schröder, H. (2014). Study protocol: Effects of the THAO-child health intervention program on the prevention of childhood obesity—The POIBC study. BMC Pediatrics, 14, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga, I., Ribovski, M., Claumann, G. S., Folle, A., Beltrame, T. S., Laus, M. F., & Pelegrini, A. (2023). Secular trends in body image dissatisfaction and associated factors among adolescents (2007–2017/2018). PLoS ONE, 18(1), e0280520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S. F., Lorenzo, L., & Ribes, C. (2023). Estudio PASOS 2022. Gasol Foundation Europa. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Mármol, A., Sánchez-Alcaraz Martínez, B. J., & Mahedero, P. (2013). Insatisfacción y distorsión de la Imagen corporal en adolescentes de doce a diecisiete años de edad. Ágora para la Educación Física y el Deporte, 15, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Grams, L., Nelius, A. K., Pastor, G. G., Sillero-Quintana, M., Veiga, Ó. L., Homeyer, D., & Kück, M. (2022). Comparison of adherence to mediterranean diet between Spanish and German school-children and influence of gender, overweight, and physical activity. Nutrients, 14(21), 4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, R. M., Urchaga, J. D., & Sanchez Moro, E. (2019). Horas de pantalla y actividad física de los estudiantes de Educación Secundaria. European Journal of Health Research, 5(2), 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrik, Z., Filakovska Bobakova, D., Kalman, M., Dankulincova Veselska, Z., Klein, D., & Madarasová Gecková, A. (2015). Physical activity and screen-based activity in healthy development of school-aged children. Central European Journal of Public Health, 23(Supplement), S50–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanewald, R. (2013). Transition between primary and secondary school: Why it is important and how it can be supported. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(1), 62–74. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1008552.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Harris, C. V., Bradlyn, A. S., Coffman, J., Gunel, E., & Cottrell, L. (2008). BMI-based body size guides for women and men: Development and validation of a novel pictorial method to assess weight-related concepts. International Journal of Obesity, 32(2), 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiman, T., & Olenik-Shemesh, D. (2019). Perceived body appearance and eating habits: The voice of young and adult students attending higher education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heredia-Bolaños, D. M., & Grisales-Romero, H. (2019). Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud de niños y adolescentes que viven en un hogar temporal, Colombia. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 17(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Ramos, E., Tomaino, L., Sánchez-Villegas, A., Ribas-Barba, L., Gómez, S. F., Wärnberg, J., Osés, M., González-Gross, M., Gusi, N., Aznar, S., Marín-Cascales, E., González-Valeiro, M. Á., Terrados, N., Tur, J. A., Segú, M., Fitó, M., Homs, C., Benavente-Marín, J. C., Labayen, I., … Serra-Majem, L. (2023). Trends in adherence to the mediterranean diet in Spanish children and adolescents across two decades. Nutrients, 15(10), 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honório, S., Santos, J., Serrano, J., Rocha, J., Petrica, J., Ramalho, A., & Batista, M. (2021). Lifelong healthy habits and lifestyles. In Sport psychology in sports, exercise and physical activity. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaimes-Valencia, M. L., Fajardo-Nates, S., Arguello, J. F., Mejía-Arciniegas, C. N., Rojas-Arenas, L. C., Gallo-Eugenio, L. M., & León-Santos, N. R. (2019). Percepciones de padres o acudientes sobre la salud y calidad de vida de sus hijos adolescentes escolarizados. MedUNAB, 21(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidscreen. (n.d.). Kidscreen. Available online: https://www.kidscreen.org/english/ (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Knebel, M. T. G., Matias, T. S., Lopes, M. V. V., dos Santos, P. C., da Silva Bandeira, A., & da Silva, K. S. (2022). Clustering of physical activity, sleep, diet, and screen-based device use associated with self-rated health in adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(5), 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C. L. K. (2010). Subjective quality of life measures—General principles and concepts. In Handbook of disease burdens and quality of life measures. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoneda-Prieto, J., & Huertas-Delgado, F. J. (2017). Motivación deportiva en la transición de primaria a secundaria. Ágora Para La Educación Física y El Deporte, 19(1), 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Lin, R., Guo, C., Xiong, L., Chen, S., & Liu, W. (2019). Prevalence of body dissatisfaction and its effects on health-related quality of life among primary school students in Guangzhou, China. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maljur, T., Matasić, K., & Lovreković, T. (2022). Too much screen time?—Perception and actual smartphone usage, gender differences and academic success. Život i Škola, 68(1–2), 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, J., Barnett, L. M., Strugnell, C., & Allender, S. (2015). Changing from primary to secondary school highlights opportunities for school environment interventions aiming to increase physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviour: A longitudinal cohort study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(1), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastorci, F., Doveri, C., Trivellini, G., Casu, A., Bastiani, L., Pingitore, A., & Vassalle, C. (2020). Sex differences in body mass index, mediterranean diet adherence, and physical activity level among italian adolescents. Health Behavior and Policy Review, 7(6), 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokari-Yamchi, A., Brazendale, K., Faghfouri, A. H., Mohammadpour, Y., & Gheibi, S. (2024). Adherence to physical activity and screen time recommendations of youth: Demographic differences from national health and nutrition examination survey 2017–2018. Obesity Science and Practice, 10(4), e776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, M., & Juan, F. (2016). Estudio longitudinal de los comportamientos y el nivel de actividad físico-deportiva en el tiempo libre en estudiantes de Costa Rica, México y España [Longitudinal study on leisure time behaviors and physical and sports activity level in students from CostaRica, Mexico, and Spain]. Retos, 31, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamed-Gorji, N., Qorbani, M., Nikkho, F., Asadi, M., Motlagh, M. E., Safari, O., Arefirad, T., Asayesh, H., Mohammadi, R., Mansourian, M., & Kelishadi, R. (2019). Association of screen time and physical activity with health-related quality of life in Iranian children and adolescents. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 17(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuviala Nuviala, A., Ruiz Juan, F., & Nuviala Nuviala, R. (2010). Actividad física y autopercepción de la salud en adolescentes. Pensar En Movimiento: Revista de Ciencias Del Ejercicio y La Salud, 8(1), 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ortiz-Sánchez, J. A., del Pozo-Cruz, J., Álvarez-Barbosa, F., & Alfonso-Rosa, R. M. (2024). Análisis longitudinal del efecto del comportamiento sedentario en la composición corporal, condición física y el rendimiento académico en preadolescentes y adolescentes. Journal of Sport Science, 20, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palenzuela-Luis, N., Duarte-Clíments, G., Gómez-Salgado, J., Rodríguez-Gómez, J. Á., & Sánchez-Gómez, M. B. (2022). Questionnaires assessing adolescents’ self-concept, self-perception, physical activity and lifestyle: A systematic review. Children, 9(1), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C. W., Zhong, H., Li, J., Suo, C., & Wang, P. (2020). Measuring health-related quality of life in elementary and secondary school students using the Chinese version of the EQ-5D-Y in rural China. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulich, K. N., Ross, J. M., Lessem, J. M., & Hewitt, J. K. (2021). Screen time and early adolescent mental health, academic, and social out comes in 9- and 10-year old children: Utilizing the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development SM (ABCD) Study. PLoS ONE, 16(9), e0256591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N., Atkin, A. J., Biddle, S. J. H., Gorely, T., & Edwardson, C. (2009). Patterns of adolescent physical activity and dietary behaviours. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N., Haycraft, E., Johnston, J. P., & Atkin, A. J. (2017). Sedentary behaviour across the primary-secondary school transition: A systematic review. In Preventive Medicine, 94, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Mármol, M., Chacón-Cuberos, R., & Castro-Sánchez, M. (2023). Autoconcepto físico en educación secundaria: Relación con factores académicos. Revista Complutense de Educación, 34(3), 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J., Yan, Y., & Yin, H. (2023). Screen time among school-aged children of aged 6–14: A systematic review. Global Health Research and Policy, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S., Qin, Z., Wang, N., Tse, L. A., Qiao, H., & Xu, F. (2020). Association of academic performance, general health with health-related quality of life in primary and high school students in China. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, P., Moreno-Maldonado, C., Moreno, C., & Rivera, F. (2019). The role of body image in internalizing mental health problems in spanish adolescents: An analysis according to sex, age, and socioeconomic status. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rei, M., Severo, M., & Rodrigues, S. (2021). Reproducibility and validity of the Mediterranean Diet Quality Index (KIDMED Index) in a sample of Portuguese adolescents. The British journal of nutrition, 126(11), 1737–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón-Macías, M. E., Zarco-Villavicencio, I. S., & Villasís-Keever, M. Á. (2021). Statistical methods for effect size analysis. Revista Alergia Mexico, 68(2), 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-López, J. P., Ruiz, J. R., Ortega, F. B., Verloigne, M., Vicente-Rodriguez, G., Gracia-Marco, L., Gottrand, F., Molnar, D., Widhalm, K., Zaccaria, M., Cuenca-García, M., Sjöström, M., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Moreno, L. A., Moreno, L. A., Gottrand, F., De Henauw, S., González-Gross, M., Gilbert, C., … Gómez Lorente, J. J. (2012). Reliability and validity of a screen time-based sedentary behaviour questionnaire for adolescents: The HELENA study. European Journal of Public Health, 22(3), 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, K., & Dollman, J. (2019). Changes in physical activity behaviour and psychosocial correlates unique to the transition from primary to secondary schooling in adolescent females: A longitudinal cohort study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocka, A., Jasielska, F., Madras, D., Krawiec, P., & Pac-Kożuchowska, E. (2022). The impact of digital screen time on dietary habits and physical activity in children and adolescents. Nutrients, 14(14), 2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A., Meigen, C., Hiemisch, A., Kiess, W., & Poulain, T. (2023). Associations between stressful life events and increased physical and psychological health risks in adolescents: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ródenas-Munar, M., Monserrat-Mesquida, M., Gómez, S. F., Wärnberg, J., Medrano, M., González-Gross, M., Gusi, N., Aznar, S., Marín-Cascales, E., González-Valeiro, M. A., Serra-Majem, L., Pulgar, S., Segu, M., Fitó, M., Torres, S., Benavente-Marín, J. C., Labayen, I., Zapico, A. G., Sánchez-Gómez, J., … Tur, J. A. (2023). Perceived quality of life is related to a healthy lifestyle and related outcomes in Spanish children and adolescents: The physical activity, sedentarism, and obesity in Spanish study. Nutrients, 15(24), 5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, K. D., Lambert, S. F., Clark, A. G., & Kurlakowsky, K. D. (2001). Negotiating the transition to middle school: The role of self-regulatory processes. Child Development, 72(3), 929–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar Mora, Z. (2008). Adolescencia e imagen corporal en la época de la delgadez. Reflexiones, 87(2), 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Santana Vega, L. E., Feliciano García, L. A., & Santana Lorenzo, A. (2012). Análisis del proyecto de vida del alumnado de educación secundaria. Revista Española de Orinetación y Psicopedagogía, 23(1), 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R. M. S., Mendes, C. G., Sen Bressani, G. Y., de Alcantara Ventura, S., de Almeida Nogueira, Y. J., de Miranda, D. M., & Romano-Silva, M. A. (2023). The associations between screen time and mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-López, M., Salcedo-Aguilar, F., Solera-Martínez, M., Moya-Martínez, P., Notario-Pacheco, B., & Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. (2009). Physical activity and quality of life in schoolchildren aged 11–13 years of Cuenca, Spain. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 19(6), 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L., Ribas, L., Ngo, J., Ortega, R. M., García, A., Pérez-Rodrigo, C., & Aranceta, J. (2004). Food, youth and the mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, mediterranean diet quality index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutrition, 7(7), 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevil Serrano, J., Abós Catalán, A., Aibar Solana, A., Sanz Remacha, M., & García-González, L. (2018). ¿Se deberían replantear las recomendaciones relativas al uso sedentario del tiempo de pantalla en adolescentes? SPORT TK-Revista EuroAmericana de Ciencias Del Deporte, 7(2), 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U., & Manju, M. (2022). Correlates of body image and self esteem among adolescents. International Journal of Health Sciences, 6(S6), 4147–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solera-Sanchez, A., Adelantado-Renau, M., Moliner-Urdiales, D., & Beltran-Valls, M. R. (2021). Health-related quality of life in adolescents: Individual and combined impact of health-related behaviors (DADOS study). Quality of Life Research, 30(4), 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollerhed, A.-C., Fransson, J., Skoog, J., & Garmy, P. (2022). Physical activity levels, perceived body appearance, and body functioning in relation to perceived wellbeing among adolescents. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4, 830913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H., Cai, Y., Cai, Q., Luo, W., Jiao, X., Jiang, T., Sun, Y., & Liao, Y. (2023). Body image perception and satisfaction of junior high school students: Analysis of possible determinants. Children, 10(6), 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, M., & Failde, I. (2004). La calidad de vida relacionada con la salud como medida de resultados en pacientes con cardiopatía isquémica. Revista de la Sociedad Espanola del Dolor, 11(8), 505–514. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglic, N., & Viner, R. M. (2019). Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open, 9(1), e023191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedberg, P., Eriksson, M., & Boman, E. (2013). Associations between scores of psychosomatic health symptoms and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11(1), 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, O., & Hallberg, L. R. M. (2011). Hunting for health, well-being, and quality of life. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 6(2), 7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambalis, K. D., Panagiotakos, D. B., Moraiti, I., Psarra, G., & Sidossis, L. S. (2018). Poor dietary habits in Greek schoolchildren are strongly associated with screen time: Results from the EYZHN (National Action for Children’s Health) program. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72(4), 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambalis, K. D., Panagiotakos, D. B., Psarra, G., & Sidossis, L. S. (2020). Screen time and its effect on dietary habits and lifestyle among schoolchildren. Central European Journal of Public Health, 28(4), 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Serrano, M. Á., Vaquero-Solís, M., López-Gajardo, M. Á., Sánchez-Miguel, P. A., Tapia-Serrano, M. Á., Vaquero-Solís, M., López-Gajardo, M. Á., & Sánchez-Miguel, P. A. (2021). Adherencia a la dieta mediterránea e importancia de la actividad física y el tiempo de pantalla en los adolescentes extremeños de enseñanza secundaria. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 38(2), 236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, M., & Mishra, S. K. (2019). Screen time and adiposity among children and adolescents:a systematic review. Journal of Public Health, 28, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2013). Mediterranean diet. Representative list of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/mediterranean-diet-00884 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- UNICEF. (2018). La infancia en Galicia 2018. UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- Urchaga, J. D., Guevara, R. M., Cabaco, A. S., & Moral-Garcia, J. E. (2020). Life satisfaction, physical activity and quality of life associated with the health of school-age adolescents. Sustainability, 12(22), 9486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ureña, P., Blanco, L., & Salas, J. (2015). Calidad de vida, indicadores antropométricos y satisfacción corporal en ungrupo de jóvenes colegiales. Retos, 27, 62–66. Available online: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/retos/article/view/34349/18530 (accessed on 14 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Urzúa, A. (2012). Calidad de vida: Una revisión teórica del concepto Quality of life: A theoretical review. Terapia Psicológica, 30, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhelst, J., Béghin, L., Drumez, E., Labreuche, J., Polito, A., De Ruyter, T., Censi, L., Ferrari, M., Miguel-Berges, M. L., Michels, N., De Henauw, S., Moreno, L. A., & Gottrand, F. (2023). Changes in physical activity patterns from adolescence to young adulthood: The BELINDA study. European Journal of Pediatrics, 182(6), 2891–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, H., Preciados, G., Minguet, C., & Luís, J. (2010). Estudio de la ocupación del tiempo libre de los escolares. Retos. Nuevas Tendencias En Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 18, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vilugrón Aravena, F., Molina, G. T., Gras Pérez, M. E., & Font-Mayolas, S. (2020). Hábitos alimentarios, obesidad y calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en adolescentes chilenos. Revista Médica de Chile, 148(7), 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Li, Y., & Fan, H. (2019). The associations between screen time-based sedentary behavior and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wärnberg, J., Pérez-Farinós, N., Benavente-Marín, J. C., Gómez, S. F., Labayen, I. G., Zapico, A., Gusi, N., Aznar, S., Alcaraz, P. E., González-Valeiro, M., Serra-Majem, L., Terrados, N., Tur, J. A., Segú, M., Lassale, C., Homs, C., Oses, M., González-Gross, M., Sánchez-Gómez, J., … Barón-López, F. J. (2021). Screen time and parents’ education level are associated with poor adherence to the mediterranean diet in Spanish children and adolescents: The PASOS study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(4), 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). WHOQOL: Measuring quality of life. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- World Health Organization. (2018). Plan de acción mundial sobre actividad física 2018–2030. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/336656/9789240015128-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Yan, H., Zhang, R., Oniffrey, T. M., Chen, G., Wang, Y., Wu, Y., Zhang, X., Wang, Q., Ma, L., Li, R., & Moore, J. B. (2017). Associations among screen time and unhealthy behaviors, academic performance, and well-being in Chinese adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(6), 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita-Ortega, F., Ubago-Jiménez, J. L., Puertas-Molero, P., González-Valero, G., Castro-Sánchez, M., & Chacón-Cuberos, R. (2018). Niveles de actividad física en alumnado de educación primaria de la provincia de Granada (Physical activity levels of primary education students in Granada). Retos, 34, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Students (n) | Frequency and Percentage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th Year Primary Education | 2° ESO | Girls | Boys | 6th Year Primary Education | 2° ESO | ||

| Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | ||||

| 73 | 94 | 68 | 70 | 141 (46.2%) | 164 (53.8%) | 167 (54.8%) | 138 (45.2%) |

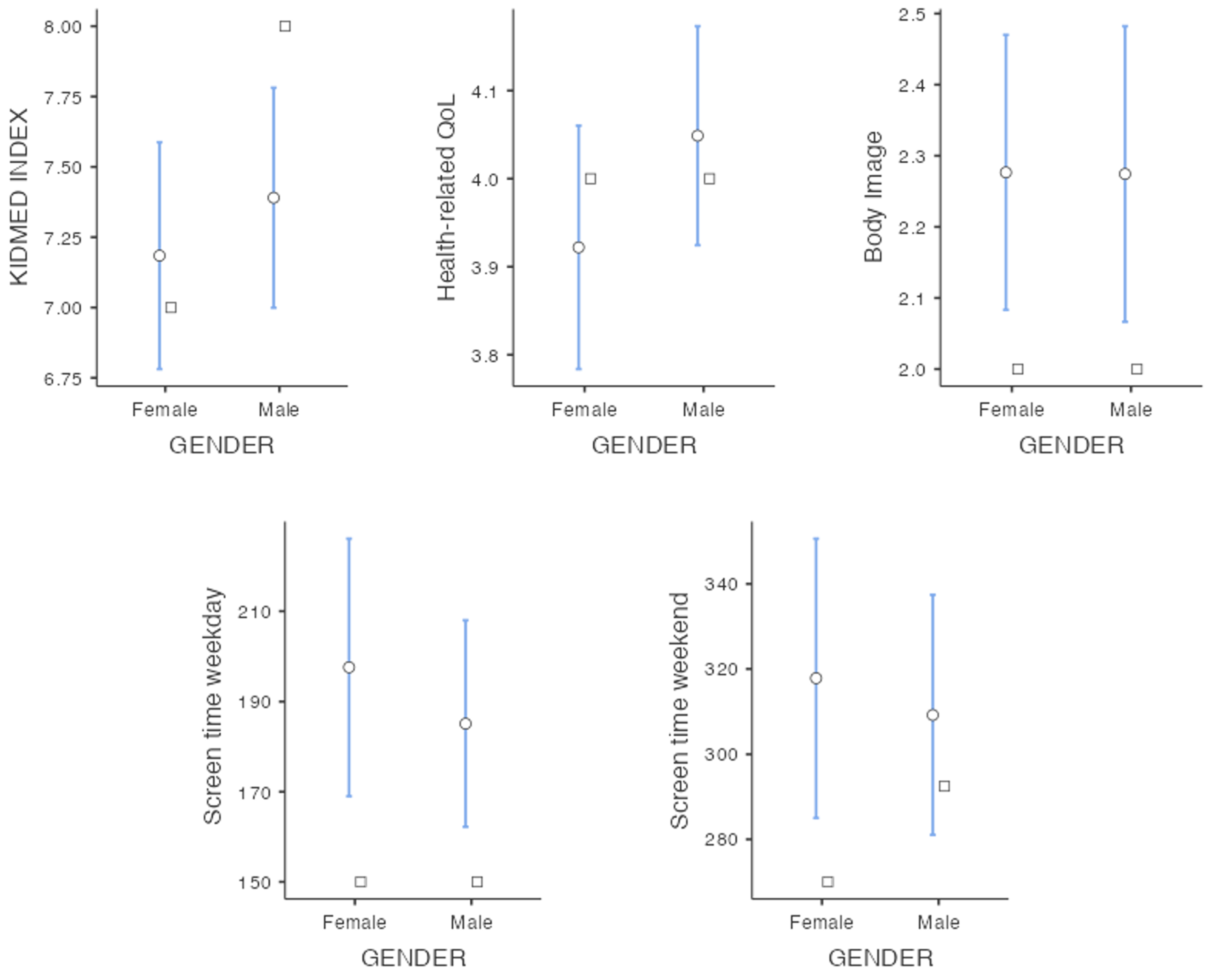

| All Participants | Male | Female | Sex Differences | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Mean | SD | Range Min/Max | CI 95% Low/Upp | Mean | SD | Range Min/Max | CI 95% Low/Upp | Mean | SD | Range Min/Max | CI 95% Low/Upp | p | d | CI 95% Low/Upp |

| Sex (M/F, n) | 164/141 | ||||||||||||||

| KIDMED index (a.u) | 7.30 | 2.50 | −2/12 | 7.01/7.58 | 7.39 | 2.55 | −2/12 | 7.00/7.78 | 7.18 | 2.44 | 0/12 | 6.78/7.59 | 0.474 | −0.082 | −0.307/0.143 |

| Screen time on weekdays (min/day) | 191.00 | 161.00 | 0/840 | 173.00/209.00 | 185.00 | 149.00 | 0/780 | 162.00/208.00 | 198.00 | 173.00 | 0/840 | 169.00/226.00 | 0.501 | 0.077 | −0.148/0.270 |

| Screen time on weekends (min/day) | 313.00 | 191.00 | 0/840 | 292.00/335.00 | 309.00 | 184.00 | 0/840 | 281.00/338.00 | 318.00 | 199.00 | 15/840 | 285.00/351.00 | 0.696 | 0.045 | −0.180/0.270 |

| Health-related quality of life (a.u) | 3.99 | 0.83 | 1/5 | 3.90/4.08 | 4.05 | 0.813 | 1/5 | 3.92/4.17 | 3.82 | 0.837 | 2/5 | 3.78/4.06 | 0.181 | −0.15 | −0.379/0.072 |

| Body image perception (a.u) | 2.28 | 1.27 | 1/5 | 2.13/2.42 | 2.27 | 1.35 | 1/8 | 2.06/2.48 | 2.28 | 1.17 | 1/6 | 2.08/2.47 | 0.988 | 0.002 | −0.223/0.227 |

| All Participants (n = 305) | Males (n = 164) | Females (n = 141) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary School (n = 167) | Secondary School (n = 138) | Primary School (n = 94) | Secondary School (n = 70) | Primary School (n = 73) | Secondary School (n = 68) | ||||||||||

| Variable | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p | d | CI 95% | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p | d | CI 95% | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p | d | CI 95% |

| KIDMED index (a.u) | 7.43 ± 2.46 | 7.14 ± 2.56 | 0.319 | 0.115 | −0.11/0.34 | 7.49 ± 2.49 | 7.26 ± 2.65 | 0.566 | 0.091 | −0.22/0.40 | 7.34 ± 2.42 | 7.01 ± 2.47 | 0.428 | 0.134 | −0.20/0.46 |

| Screen time on weekdays (min/day) | 159.00 ± 148.00 | 229.00 ± 167.00 | <0.001 | −0.446 | −0.67/−0.22 | 151.00 ± 134.00 | 231.00 ± 158.00 | <0.001 | −0.550 | −0.87/0.23 | 169.00 ± 164.00 | 228.00 ± 178.00 | 0.045 | −0.341 | −0.68/−0.01 |

| Screen time on weekends (min/day) | 283.00 ± 181.00 | 349.00 ± 197.00 | 0.002 | −0.351 | −0.58/−0.12 | 260.00 ± 158.00 | 375.00 ± 197.00 | <0.001 | −0.656 | −0.98/−0.33 | 313.00 ± 205.00 | 323.00 ± 194.00 | 0.774 | −0.049 | −0.37/0.29 |

| Health-perception quality of life (a.u) | 4.19 ± 0.68 | 3.75 ± 0.92 | <0.001 | 0.541 | 0.31/0.78 | 4.19 ± 0.68 | 3.86 ± 0.94 | 0.009 | 0.419 | 0.10/0.73 | 4.18 ± 0.67 | 3.65 ± 0.90 | 0.001 | −0.666 | 0.32/1.01 |

| Perception of body image (a.u) | 2.09 ± 1.14 | 2.50 ± 1.38 | 0.005 | −0.326 | −0.55/−0.10 | 1.94 ± 1.15 | 2.73 ± 1.48 | <0.001 | −0.608 | −0.93/−0.29 | 2.29 ± 1.09 | 2.26 ± 1.25 | 0.908 | 0.020 | −0.32/0.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garrido-López, B.; Fernández-Villarino, M.Á.; González-Valeiro, M.; Andreu-Caravaca, L.; Martins, J.; Dopico-Calvo, X. Gender Differences in Eating Habits, Screen Time, Health-Related Quality of Life and Body Image Perception in Primary and Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Spain. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040470

Garrido-López B, Fernández-Villarino MÁ, González-Valeiro M, Andreu-Caravaca L, Martins J, Dopico-Calvo X. Gender Differences in Eating Habits, Screen Time, Health-Related Quality of Life and Body Image Perception in Primary and Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Spain. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):470. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040470

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarrido-López, Beatriz, Mª Ángeles Fernández-Villarino, Miguel González-Valeiro, Luis Andreu-Caravaca, João Martins, and Xurxo Dopico-Calvo. 2025. "Gender Differences in Eating Habits, Screen Time, Health-Related Quality of Life and Body Image Perception in Primary and Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Spain" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040470

APA StyleGarrido-López, B., Fernández-Villarino, M. Á., González-Valeiro, M., Andreu-Caravaca, L., Martins, J., & Dopico-Calvo, X. (2025). Gender Differences in Eating Habits, Screen Time, Health-Related Quality of Life and Body Image Perception in Primary and Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Spain. Education Sciences, 15(4), 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040470