Managing Stress During Long-Term Internships: What Coping Strategies Matter and Can a Workbook Help?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Teacher Stress, Coping, and the Need for Intervention

1.2. The School-Based Internship and Its Stressors

1.3. Coping Strategies and Interventions During School-Based Internships

1.4. The Intervention and the Present Study

1.5. Research Questions

- (1)

- Coping strategies and occupational well-being

- (a)

- How prominent are pre-service teachers’ occupational well-being, their coping strategies, and their experience of internship-related stressors at the beginning and end of their long-term internship?

- (b)

- How do occupational well-being and coping strategies evolve during the long-term internship?

- (2)

- Predictive role of coping strategies

- (3)

- Perceived usefulness of the workbook

- (4)

- Engagement with the workbook

- (a)

- To what extent did pre-service teachers engage with the self-directed workbook during their long-term internship?

- (b)

- What content in the workbook did they find most helpful?

- (c)

- What factors hindered their engagement and what additional support might have facilitated greater engagement?

- (5)

- Effectiveness of the workbook

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

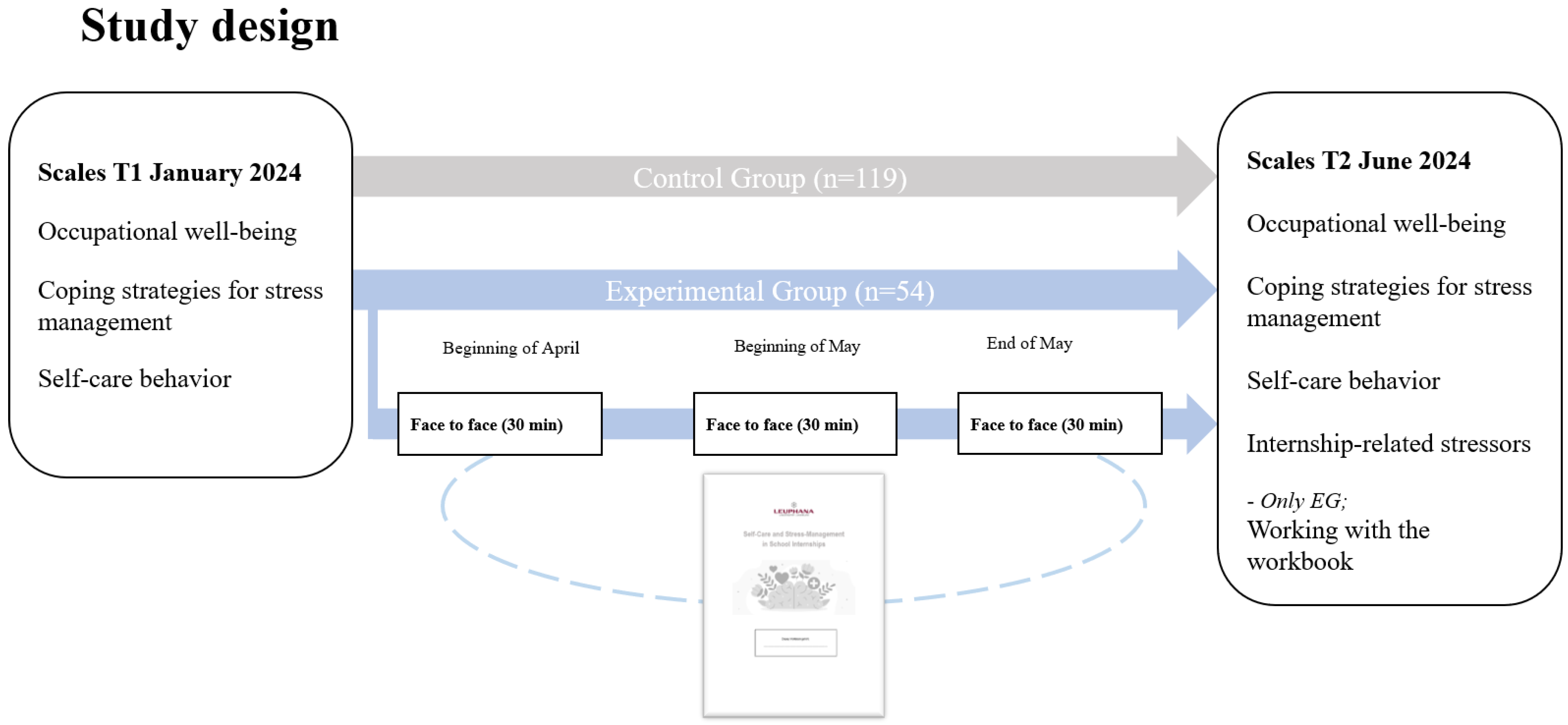

2.2. Procedure

2.3. The Intervention

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Occupational Well-Being

2.4.2. Coping Strategies

2.4.3. Internship-Related Stressors

2.4.4. Evaluation of the Intervention

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Research Question 1: Coping Strategies and Occupational Well-Being

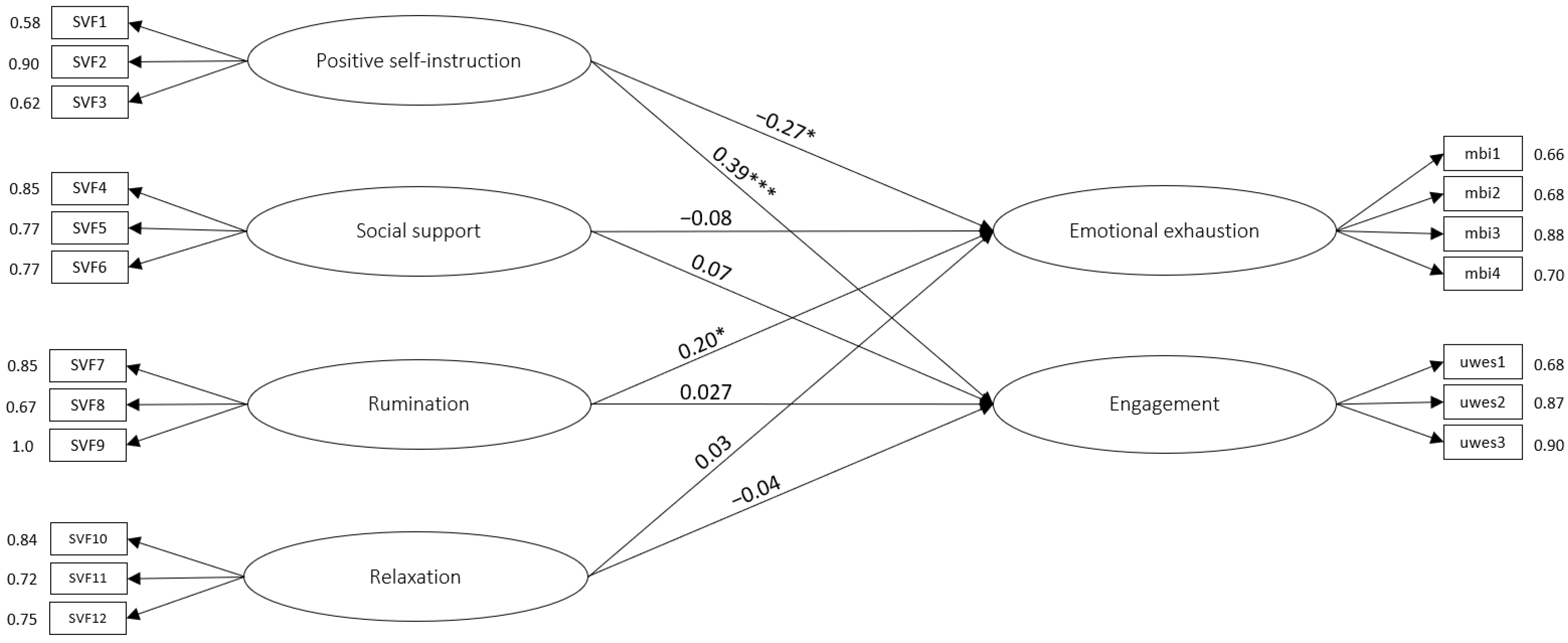

3.2. Research Question 2: Predictive Role of Coping Strategies

3.3. Research Question 3: Perceived Usefulness of the Workbook

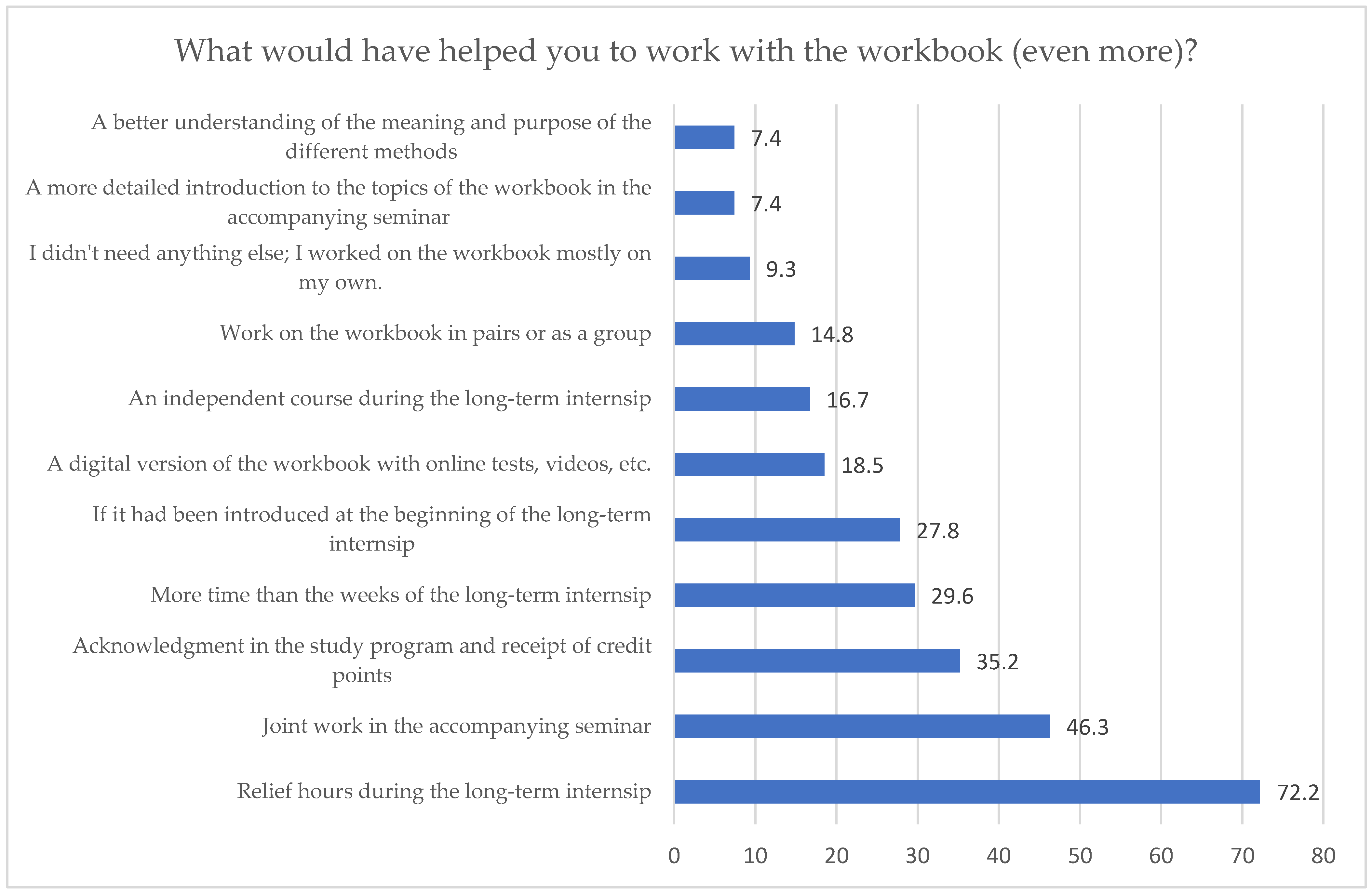

3.4. Research Question 4: Engagement with the Workbook

3.5. Research Question 5: Effectiveness of the Workbook

4. Discussion

4.1. Manifestation of Coping Strategies and Occupational Well-Being

4.2. The Impact of Cognitive Coping Strategies

4.3. Effectiveness of the Workbook Intervention

4.4. Practical Implications

4.5. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atkins, M. A., & Rodger, S. (2016). Pre-service teacher education for mental health and inclusion in schools. Exceptionality Education International, 26(2), 7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulén, A. M., Pakarinen, E., Feldt, T., & Lerkkanen, M. K. (2021). Teacher coping profiles in relation to teacher well-being: A mixed method approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 102, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2021). Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 34(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbeau, K., Boileau, K., Sarr, F., & Smith, K. (2019). Path analysis in mplus: A tutorial using a conceptual model of psychological and behavioral antecedents of bulimic symptoms in young adults. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 15(1), 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardach, L., Klassen, R. M., & Perry, N. E. (2022). Teachers’ psychological characteristics: Do they matter for teacher effectiveness, teachers’ well-being, retention, and interpersonal relations? An integrative review. Educational Psychology Review, 34(1), 259–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumert, J., & Kunter, M. (2013). The COACTIV model of teachers’ professional competence. In Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers: Results from the COACTIV project (pp. 25–48). Springer US. [Google Scholar]

- Beltman, S., Mansfield, C., & Price, A. (2011). Thriving not just surviving: A review of research on teacher resilience. Educational Research Review, 6(3), 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchinall, L., Spendlove, D., & Buck, R. (2019). In the moment: Does mindfulness hold the key to improving the resilience and wellbeing of pre-service teachers? Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böke, B. N., Petrovic, J., Zito, S., Sadowski, I., Carsley, D., Rodger, S., & Heath, N. L. (2024). Two for one: Effectiveness of a mandatory personal and classroom stress management program for preservice teachers. School Psychology, 39(3), 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S. S., & Hooper, A. L. (2024). Social and emotional competencies predict pre-service teachers’ occupational health and personal well-being. Teaching and Teacher Education, 147, 104654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S. S., Roeser, R. W., Mashburn, A. J., & Skinner, E. (2019). Middle school teachers’ mindfulness, occupational health and well-being, and the quality of teacher-student interactions. Mindfulness, 10(2), 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, M., Küth, S., Scholl, D., & Schüle, C. (2021). Ressource oder Belastung? Zeitschrift für Bildungsforschung, 11(2), 291–308. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A., Forrest, K., Sanders-O’Connor, E., Flynn, L., Bower, J. M., Fynes-Clinton, S., York, A., & Ziaei, M. (2022). Teacher stress and burnout in Australia: Examining the role of intrapersonal and environmental factors. Social Psychology of Education, 25(2–3), 441–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A. Y., Leigh, T. N., Böke, B. N., Wang, H., So, C. N., & Heath, N. (2025). Evaluation of a wellness programme for preservice teachers in Hong Kong: Promoting educational excellence through resilience to stress (PEERS). European Journal of Education, 60(1), e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplain, R. P. (2008). Stress and psychological distress among trainee secondary teachers in England. Educational Psychology, 28(2), 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E., Hoz, R., & Kaplan, H. (2013). The practicum in preservice teacher education: A review of empirical studies. Teaching Education, 24(4), 345–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J., & Mansfield, C. F. (2022). Teacher and school stress profiles: A multilevel examination and associations with work-related outcomes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 116, 103759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, R. P., & O’Flaherty, J. (2022). Social and emotional learning in teacher preparation: Pre-service teacher well-being. Teaching and Teacher Education, 110, 103563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, R. P., & Tormey, R. (2012). How emotionally intelligent are pre-service teachers? Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(5), 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, C., Friedrich, A., & Merk, S. (2018). Belastung und Beanspruchung im Lehrerinnen-und Lehrerberuf: Übersicht zu Theorien, Variablen und Ergebnissen in einem integrativen Rahmenmodell. Bildungsforschung, (1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebi, C., Krahé, B., & Spörer, N. (2014). Gestärkt in den Lehrerberuf: Eine Förderung berufsbezogener Kompetenzen von Lehramtsstudierenden. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 28(3), 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darge, K., Valtin, R., Kramer, C., Ligtvoet, R., & König, J. (2018). Die Freude an der Schulpraxis: Zur differenziellen Veränderung eines emotionalen Merkmals von Lehramtsstudierenden während des Praxissemesters. In Learning to practice, learning to reflect? (pp. 241–264) Springer VS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). Teacher education and the American future. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekeyser, S., Caesens, G., & Hanin, V. (2025). Preservice teachers’ profiles of emotional competences: Associations with stress, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion during practicum. Psychology in the Schools. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewhurst, Y., Ronksley-Pavia, M., & Pendergast, D. (2020). Preservice teachers’ sense of belonging during practicum placements. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 45(11), 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, T. (2016). “Doppelter Praxisschock” auf dem Weg ins Lehramt? Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 63(4), 244–257. [Google Scholar]

- Dupriez, V., Delvaux, B., & Lothaire, S. (2016). Teacher shortage and attrition: Why do they leave? British Educational Research Journal, 42(1), 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, M., & Tarnowski, T. (2017). Stress-und emotionsregulation. Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann, G., & Janke, W. (2008). Stressverarbeitungsfragebogen: SVF; Stress, Stressverarbeitung und ihre Erfassung durch ein mehrdimensionales Testsystem. Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Fives, H., Hamman, D., & Olivarez, A. (2007). Does burnout begin with student-teaching? Analyzing efficacy, burnout, and support during the student-teaching semester. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(6), 916–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J. (2015). Gesund bleiben im Lehrerberuf. Ein ressourcenorientiertes Handbuch. Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Abeledo, E. J., González-Sanmamed, M., Muñoz-Carril, P. C., & Veiga-Rio, E. J. (2020). Teacher training and learning to teach: An analysis of tasks in the practicum. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(3), 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carmona, M., Marín, M. D., & Aguayo, R. (2019). Burnout syndrome in secondary school teachers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 22, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiser, C. (2011). Latent-class-analyse. In Datenanalyse mit Mplus. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, A., & Kauffeld, S. (2013). Evaluating training programs: Development and correlates of the questionnaire for professional T raining E valuation. International Journal of Training and Development, 17(2), 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröschner, A. (2012). Langzeitpraktika in der Lehrerinnen-und Lehrerausbildung. Für und wider ein innovatives Studienelement im Rahmen der Bologna-Reform [Internships in pre-service teacher education—Pros and Cons of an innovative element in the context of the bologna process]. Beiträge zur Lehrerbildung, 30(2), 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröschner, A., & de Zordo, L. (2021). Lehrerbildung in der Hochschule. In T. Hascher, T. S. Idel, & W. Helsper (Eds.), Handbuch schulforschung. Springer VS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustems-Carnicer, J., & Calderón, C. (2013). Coping strategies and psychological well-being among teacher education students: Coping and well-being in students. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T., Beltman, S., & Mansfield, C. (2021). Teacher wellbeing and resilience: Towards an integrative model. Educational Research, 63(4), 416–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, K. C., Hickmon-Rosa, J., & Reinke, W. M. (2018). Empirically derived profiles of teacher stress, burnout, selfefficacy, and coping and associated student outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(2), 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, K. C., Prewett, S. L., Eddy, C. L., Savala, A., & Reinke, W. M. (2020). Profiles of middle school teacher stress and coping: Concurrent and prospective correlates. Journal of School Psychology, 78, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillert, A., Bracht, M., Koch, S., Lüdtke, K., Ueing, S., Lehr, D., & Sosnowsky-Waschek, N. (2019). Arbeit und Gesundheit im Lehrerberuf (AGIL). Schattauer. [Google Scholar]

- Hohensee, E., & Schiemann, S. (2021). Health and health literacy in teacher education: Comparative analyses of student teachers and teacher trainees. Pedagogical Quarterly, 66(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homann, H. S., Ehmke, T., & Beckmann, T. (2024). Empirische Arbeit: Belastungserleben im Praxissemester–Wie erleben Lehramtsstudierende praktikumsinhärente Belastungsfaktoren? Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 2024(0). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iancu, A. E., Rusu, A., Măroiu, C., Păcurar, R., & Maricuțoiu, L. P. (2018). The effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing teacher burnout: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadinia, M. (2016). Preservice teachers’ professional identity development and the role of mentor teachers. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 5(2), 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y., Oubibi, M., Chen, S., Yin, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ emotional experience: Characteristics, dynamics and sources amid the teaching practicum. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 968513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluza, G. (1997). Evaluation von Stressbewältigungstrainings in der primären Prävention–eine Meta-Analyse (quasi-) experimenteller Feldstudien. Zeitschrift für Gesundheitspsychologie, 5(3), 149–169. [Google Scholar]

- Karabinski, T., Haun, V. C., Nübold, A., Wendsche, J., & Wegge, J. (2021). Interventions for improving psychological detachment from work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26(3), 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karing, C., & Beelmann, A. (2016). Implementation und Evaluation eines multimodalen Stressbewältigungstrainings bei Lehramtsstudierenden. Zeitschrift für Gesundheitspsychologie. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T. (2012). Development of the Coping Flexibility Scale: Evidence for the coping flexibility hypothesis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(2), 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, D. L., & Kirkpatrick, J. D. (2006). Evaluating training programs (The four levels, 3rd ed.). Berrett-Koehler. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, R. M., & Durksen, T. L. (2014). Weekly self-efficacy and work stress during the teaching practicum: A mixed methods study. Learning and Instruction, 33, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, U., Aldrup, K., Schmidt, J., & Lüdtke, O. (2021). Is emotional exhaustion only the result of work experiences? A diary study on daily hassles and uplifts in different life domains. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 34(2), 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Voss, T., & Baumert, J. (2012). Berufliche Beanspruchung angehender Lehrkräfte: Die Effekte von Persönlichkeit, pädagogischer Vorerfahrung und professioneller Kompetenz. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, U., Richter, D., & Lüdtke, O. (2016). Teachers’ emotional exhaustion is negatively related to students’ achievement: Evidence from a large-scale assessment study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(8), 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C. M., & Stavropoulos, G. (2016). Burning out during the practicum: The case of teacher trainees. Educational Psychology, 36(3), 548–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawiec, V., Fischer, A., & Hänze, M. (2020). Demands and exhaustion while practical training in teacher education. Praxissemester im Lehramtsstudium in Deutschland: Wirkungen auf Studierende, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunter, M., Baumert, J., Leutner, D., Terhart, E., Seidel, T., Dicke, T., Holzberger, D., Kunina-Habenicht, O., Linninger, C., Lohse-Bossenz, H., Schulze-Stocker, F., & Stürmer, K. (2016). Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente der Projektphasen des BilWiss-Forschungsprogrammsn von 2009 bis 2016. IQB. [Google Scholar]

- Kücholl, D., Westphal, A., Lazarides, R., & Gronostaj, A. (2019). Beanspruchungsfolgen Lehramtsstudierender im Praxissemester. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 22(4), 945–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P. S., Yuen, M. T., & Chan, R. M. (2005). Do demographic characteristics make a difference to burnout among Hong Kong secondary school teachers? Social Indicators Research, 71, 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Le Cornu, R. (2009). Building resilience in pre-service teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(5), 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Sanchez, K., & Schwinger, M. (2023). Development and validation of the marburg self-regulation questionnaire for teachers (MSR-T). Trends in Higher Education, 2(3), 434–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Sanchez, K., & Schwinger, M. (2024). Effects of individualised and general self-regulation online training on teachers’ self-regulation, well-being, and stress. Trends in Higher Education, 3(2), 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, F. (2016). Practicum stress and coping strategies of pre-service English language teachers. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 232, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., Broadley, T., & Weatherby-Fell, N. (2016). Building resilience in teacher education: An evidenced informed framework. Teaching and Teacher Education, 54, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., & Weatherby-Fell, N. (2020). “I actually felt more confident”: An online resource for enhancing pre-service teacher resilience during professional experience. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 45(4), 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattern, J. (2012). Selbstregulation im Lehrerberuf: Entwicklung eines Trainings für angehende Lehrkräfte. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 40(2), 156–173. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, C. J., Lambert, R. G., Lineback, S., Fitchett, P., & Baddouh, P. G. (2016). Assessing teacher appraisals and stress in the classroom: Review of the classroom appraisal of resources and demands. Educational Psychology Review, 28, 577–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, J., Hennissen, P., & Loughran, J. (2017). Developing pre-service teachers’ professional knowledge of teaching: The influence of mentoring. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. Available online: https://bit.ly/4djsjSy (accessed on 24 September 2016).

- Nalipay, M. J. N., King, R. B., Mordeno, I. G., & Wang, H. (2022). Are good teachers born or made? Teachers who hold a growth mindset about their teaching ability have better well-being. Educational Psychology, 42(1), 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawab, A. (2024). Exploring the dilemmas and their influence on teacher identity development during practicum: Implications for initial teacher education. International Social Science Journal, 74(251), 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. D., & Springer, M. G. (2023). A conceptual framework of teacher turnover: A systematic review of the empirical international literature and insights from the employee turnover literature. Educational Review, 75(5), 993–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S., Roberto, M. S., Pereira, N. S., Marques-Pinto, A., & Veiga-Simão, A. M. (2021). Impacts of social and emotional learning interventions for teachers on teachers’ outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 677217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J., Loughland, T., Collie, R. J., Kingsford-Smith, A. A., Ryan, M., Mansfield, C., Davey, R., Monteleone, C., & Tanti, M. (2025). The impact of practicum job demands and resources on pre-service teachers’ occupational commitment and job intent. Teaching and Teacher Education, 153, 104841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieter, A., & Wolf, G. (2014). Effects of stress reduction interventions on psychological well-being in working environments: A meta-analytic review. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung, 9, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redín, C. I., & Erro-Garcés, A. (2020). Stress in teaching professionals across Europe. International Journal of Educational Research, 103, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeser, R. W., Mashburn, A. J., Skinner, E. A., Taylor, C., Choles, J. R., Rickert, N. P., Pinela, C., Robbeloth, J., Saxton, E., Weiss, E., Cullen, M., & Sorenson, J. (2022). Mindfulness training improves middle school teachers’ occupational health, well-being, and interactions with students in their most stressful classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(2), 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudow, B. (1994). Die arbeit des lehrers. Huber. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, T., Diessner, R., & Reade, L. (2009). Strengths only or strengths and relative weaknesses? A preliminary study. The Journal of Psychology, 143(5), 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaarschmidt, U., & Fischer, A. W. (1997). AVEM—Ein diagnostisches Instrument zur Differenzierung von Typen gesundheitsrelevanten Verhaltens und Erlebens gegenuber der Arbeit. Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie, 18, 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Schaarschmidt, U., & Kieschke, U. (2007). Gerüstet für den Schulalltag. Psychologische Unterstützungsangebote für Lehrerinnen und Lehrer. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2003). Utrecht work engagement scale-9. Educational and Psychological Measurement. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Shimazu, A., Hakanen, J., Salanova, M., & De Witte, H. (2017). An ultra-short measure for work engagement. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Kitil, M. J., & Hanson-Peterson, J. (2017). To reach the students, teach the teachers: A national scan of teacher preparation and social and emotional learning. In Report prepared for the collaborative for academic, social, and emotional learning (CASEL). University of British Columbia. [Google Scholar]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2016). Teacher stress and teacher self-efficacy as predictors of engagement, emotional exhaustion, and motivation to leave the teaching profession. Creative Education, 7(13), 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, V., Walker, K., & Spurr, S. (2022). Understanding self perceptions of wellbeing and resilience of preservice teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 118, 103828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerktorun, Y. Z., Weiher, G. M., & Horz, H. (2020). Psychological detachment and work-related rumination in teachers: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 31, 100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, Y. Z., Weiher, G. M., Wendsche, J., & Lohmann-Haislah, A. (2021). Difficulties detaching psychologically from work among german teachers: Prevalence, risk factors and health outcomes within a cross-sectional and national representative employee survey. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, Y. Z., Weiher, G. M., Wenzel, S. F. C., & Horz, H. (2023). Practicum in teacher education: The role of psychological detachment and supervisors’ feedback and reflection in student teachers’ well-being. European Journal of Teacher Education, 47(5), 933–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väisänen, S., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Toom, A., & Soini, T. (2018). Student teachers’ proactive strategies for avoiding study-related burnout during teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(3), 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D. T., & Allen, K. A. (2022). A systematic review of school-based positive psychology interventions to foster teacher wellbeing. Teachers and Teaching, 28(8), 964–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, I., Noichl, T., Cramer, M., Dlugosch, G. E., & Hosenfeld, I. (2024). Moderating personal factors for the effectiveness of a self-care-and mindfulness-based intervention for teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 144, 104576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., & Hall, N. C. (2018). A systematic review of teachers’ causal attributions: Prevalence, correlates, and consequences. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H., & Hall, N. C. (2021). Exploring relations between teacher emotions, coping strategies, and intentions to quit: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 86, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weldon, P. (2018). Early career teacher attrition in Australia: Evidence, definition, classification and measurement. Australian Journal of Education, 62(1), 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, S., Sebastian, J., Herman, K. C., Huang, F. L., Reinke, W. M., & Thompson, A. M. (2023). The relationship between teacher stress and job satisfaction as moderated by coping. Psychology in the Schools, 60(7), 2237–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, S., Petrovic, J., Böke, B. N., Sadowski, I., Carsley, D., & Heath, N. L. (2024). Exploring the stress management and well-being needs of pre-service teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 152, 104805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MODULE 1 RECOGNIZING | My symptoms of stress Stress and Gratitude Journal Focusing on strengths My stressors during the internship AVEM self-test Analyzing time management skills Positive and negative stress |

| MODULE 2 TAKING ACTION | Three ways of dealing with stress: the ABC model Systematic problem-solving and goal-setting Control beliefs and a growth mindset Questioning which personal beliefs are stress-boosters Shifting perspectives through cognitive restructuring Setting boundaries: learning to say NO Appropriate ideals Mindfulness Practical tips: How to avoid stress in school life (and during internships)? What can I change? The IF…, THEN… plan! |

| MODULE 3 MY RESOURCES | What can’t I change? The power of acceptance Self-complexity—How to nourish the diversity within you Having a purpose: a sense of coherence Embracing success and fostering resilience The power of a social network Recovery: my to-relax list Conclusion: What’s essential for our health when teaching (and in life) |

| Scale | Example Items | Nr. of Items | α at T1 | α at T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational well-being | ||||

| Engagement |

| 3 | 0.80 | 0.86 |

| Emotional exhaustion |

| 4 | 0.80 | 0.85 |

| Coping strategies | ||||

Stress management

| If I have been affected by something or someone during my studies/internship, if I have been upset or out of balance…

| 12 | 0.76 | 0.80 |

| Self-care behavior |

| 12 | 0.77 | 0.78 |

| Internship-related stressors | ||||

|

| 5 | x | 0.80 |

|

| 4 | x | 0.77 |

|

| 3 | x | 0.75 |

|

| 4 | x | 0.61 |

| Training Evaluation |

| 10 | x | 0.92 |

| Measurement Point | T1 | T2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale: | N | Range | Mean | Std. Deviation | N | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| Occupational well-being: | |||||||

| Emotional exhaustion | 189 | 1–4 | 2.09 | 0.65 | 174 | 2.07 | 0.73 |

| Engagement | 189 | 1–4 | 2.10 | 0.61 | 174 | 2.57 | 0.77 |

| Coping strategies | |||||||

| Positive self-instruction | 186 | 1–4 | 2.94 | 0.56 | 173 | 2.93 | 0.60 |

| Social support | 186 | 1–4 | 2.68 | 0.78 | 173 | 2.90 | 0.79 |

| Rumination | 186 | 1–4 | 2.80 | 0.86 | 173 | 2.70 | 0.83 |

| Relaxation | 186 | 1–4 | 2.23 | 0.71 | 173 | 2.15 | 0.72 |

| Self-care behavior | 188 | 1–4 | 2.77 | 0.43 | 173 | 2.80 | 0.44 |

| Internship-related stressors | |||||||

| School-work and organization | - | 1–4 | - | - | 174 | 1.85 | 0.73 |

| Behavior of the students | - | 1–4 | - | - | 173 | 1.73 | 0.60 |

| Insecurities about own professional behavior | - | 1–4 | - | - | 173 | 1.93 | 0.70 |

| University work and organization | - | 1–4 | - | - | 174 | 2.55 | 0.54 |

| Engagement | Emotional Exhaustion | Positive Self-Instruction | Social Support | Rumination | Relaxation | School-Work and Organization | Behavior of the Students | Insecurities About Own Professional Behavior | University Work and Organization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | −0.78 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.17 * | −0.16 * | 0.08 | −0.72 *** | −0.19 * | −0.33 *** | −0.37 *** |

| - | - | −0.40 *** | −0.153 | 0.37 *** | −0.11 | 0.76 *** | 0.22 | 0.49 *** | 0.74 *** |

| - | - | - | 0.31 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.27 ** | −0.35 *** | −0.28 ** | −0.50 *** | −0.37 *** |

| - | - | - | - | 0.07 | 0.33 *** | −0.14 | −0.12 | −0.21 * | −0.08 |

| - | - | - | - | - | −0.23 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.19 * | 0.46 *** | 0.29 ** |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.07 | −0.15 | −0.26 | −0.22 |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.16 | 0.35 *** | 0.40 ** |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.48 *** | 0.17 |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.38 *** |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| (a) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Criterion | |||||||||||||||

| Engagement | Emotional exhaustion | Self-care behavior | ||||||||||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||||

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |||||

| Step 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Baseline measure at T1 | 0.44 *** | 0.09 | 0.45 *** | 0.09 | 0.44 *** | 0.08 | 0.44 *** | 0.08 | 0.53 *** | 0.07 | 0.53 *** | 0.07 | ||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Frequency of use | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.02 | ||||||||||

| R2 | 0.19 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.28 *** | ||||||||||

| Note: *** p < 0.001; multicollinearity statistics: 0.99 < tolerance < 1.00, 1.00 < VIF < 1.009 | ||||||||||||||||

| (b) | ||||||||||||||||

| Predictor | Criterion | |||||||||||||||

| Positive self-instruction | Social support | Rumination | Relaxation | |||||||||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Step 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Baseline measure at T1 | 0.37 *** | 0.08 | 0.37 *** | 0.08 | 0.55 *** | 0.07 | 0.55 *** | 0.07 | 0.51 *** | 0.06 | 0.51 *** | 0.07 | 0.50 *** | 0.07 | 0.50 *** | 0.07 |

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Frequency of use | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.14 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.24 *** | ||||||||

| Note: *** p < 0.001; multicollinearity statistics: 0.99 < tolerance < 1.00, 1.00 < VIF < 1.002 | ||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Homann, H.-S.; Ehmke, T. Managing Stress During Long-Term Internships: What Coping Strategies Matter and Can a Workbook Help? Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050532

Homann H-S, Ehmke T. Managing Stress During Long-Term Internships: What Coping Strategies Matter and Can a Workbook Help? Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):532. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050532

Chicago/Turabian StyleHomann, Hanna-Sophie, and Timo Ehmke. 2025. "Managing Stress During Long-Term Internships: What Coping Strategies Matter and Can a Workbook Help?" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050532

APA StyleHomann, H.-S., & Ehmke, T. (2025). Managing Stress During Long-Term Internships: What Coping Strategies Matter and Can a Workbook Help? Education Sciences, 15(5), 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050532