Abstract

Research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in rural, urban, and suburban public schools in southwestern Pennsylvania indicated that families and school educators and leaders had different views on education and that more needed to be done to build family, school, and community partnerships. The Parents as Allies Partnership, a collective of community, education, and research institutions, emerged out of this study and has led the co-creation of a human-centered design process with school teams on how to radically reimagine and support family, school, and community collaboration in southwestern Pennsylvania. Through the human-centered design process, teams of families, teachers, staff, and school leaders develop innovative solutions together to address pressing needs they identify in their communities. This article details this community-building process alongside case studies of three schools and how they have used the research to launch deeper and more inclusive and equitable familycentric partnership practices. This study challenges educators, researchers, and parent organizations to think differently about family, school, and community engagement and provides an evidence-based process to apply in their own contexts.

1. Introduction

As was observed across the US during the COVID-19 pandemic, family and school relations were enhanced in some districtsand strained in others. Disagreements on a range of topics, such as how to reinstate in-person learning, learning loss, and what curricula should be taught, cropped up across the US and the world (Stelmach, 2020; Ziegler & Winthrop, 2022). In southwestern Pennsylvania (SW PA), research conducted at the height of the pandemic identified an urgency of (re)imaging family, school, and community partnerships to be more “familycentric” (Pushor, 2015), placing families at the center as opposed to the periphery of their children’s learning. The research indicated that while families, educators, and students were rarely on the same page when it came to the purpose of education and views on teaching and learning, intentional conversations and partnerships could help build deeper partnerships (Winthrop et al., 2021). Findings showed that when schools took time to capture families’, educators’, and students’ beliefs on and experiences with education and then used these data for intentional dialogues, they were able to cut through social and political differences and focus on strategies to support their children. As one superintendent said, data “immediately cut through the tensions in the community. It was like everyone exhaled. People started listening” (interview with superintendent, April 2022).

Through this initial collaborative research conducted in SW PA with district and school leaders, a community organization (Kidsburgh), and a research institution (the Brookings Institution), the Parents as Allies Partnership (“the Partnership”) was conceived. While beliefs on and experiences with education varied across families and school educators (teachers, staff, and education leaders), everyone in school communities seemed to agree on one thing—the transformation of schools to better support students must be conducted in partnership with families (Winthrop et al., 2021). This Partnership was created to fill a gap in both research and practice. This article shares the background to the Partnership and the familycentric design process that emerged from the initial research. Three case studies document how the human-centered design process helped rural, urban, and suburban schools build stronger family, school, and community partnerships. A discussion on the lessons learned from the process follows, alongside critical next steps needed to further family, school, and partnerships within SW PA and beyond.

Background to the Partnership

The Partnership was launched in 2020 after a foundation in SW PA committed funds to develop a community-driven and human-centered design process to (re)imagine family and school partnerships to be more family-centric in response to the initial research. Kidsburgh, a community organization based in the region’s largest city of Pittsburgh, was selected to lead the Partnership based on their deep connections to schools and families. Throughout the research and development phase (2021–2023), the Brookings Institution continued to serve as a partner, and experts in family and school partnerships at Learning Heroes and HundrED, respectively, helped mentor school teams and document their processes. In the 2021–2022 school year, 11 schools joined the process, followed by 22 schools in 2022–2023 and 31 schools in 2022–2024 and again in 2024–2025.

The design sprint process, which was used to build family, school, and community collaborations and partnerships, was developed over the first years of the Partnership. The term “design sprint” was coined by the tech and design industry and is used by institutions like the United Nations to spur creativity, optimism, and conversation in short and innovation-focused sprints (Knapp et al., 2016). Design sprints have increasingly been used in schools and classrooms to provide educators with limited time and financial resources an innovative and collaborative solution to address common challenges (see Dunn, 2025, for an example). Throughout the design sprint process, teams work to mutually identify the assets they bring to the collaboration, their aspirations for their schools, and the barriers to engaging families that need to be addressed.

In the Partnership, the design sprint school teams are a mixed group of four to seven parents/caregivers and educators, with mentorship and support provided by outside facilitators. The design sprint process starts with the school teams reflecting on their needs and the school landscape. This is followed by designing a collaborative approach, the testing of ideas, reflecting on designs, and refining and integrating designs into more sustained practice and systems change. Critical dialogues within and between school teams are used throughout the process to build greater relational trust. Foundational research indicates that when educators and families have innovative and participatory processes to guide them in building partnerships and practices, students, schools, and families benefit (Epstein et al., 2018; Mapp et al., 2022; Winthrop et al., 2021). This article shows how design sprints, alongside the mentorship and resources provided by the Partnership, allowed three schools in SW PA to (re)imagine family, school, and community partnerships in their school contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

The design sprint process is praxis-oriented, where reflection plus action are critical for transformation (Freire, 1974). As a community-led and participatory process, design sprints operate on three key principles: (a) centering the needs, wants, assets, and expertise of school communities (families, students, and educators); (b) respecting diverse ways of knowing, thinking, and working to drive mutual learning; and (c) co-creating and critically reflecting together to implement meaningful change. Critical dialogues and reflection are intentional and constant practices throughout the process, as is identifying and positioning one’s vulnerabilities as a parent/caregiver or educator. Participation in the school team is voluntary, but representatives must include at least three parents/caregivers from diverse backgrounds and two educators—one classroom teacher and one school staff member, such as a counselor or school leader. The team is co-led by a parent/caregiver and an educator. School teams collectively agree to champion the design sprint process in their schools, to embrace the key principles, and to actively listen to families’ and students’ hopes for and barriers to engaging with schools.

The design sprint process builds relational trust through reflection, critical dialogues, and collaboration. Relational trust includes respect, integrity (keeping one’s word and translating word into action), care and mutual regard, and competence (believing in each other’s skills) (Bryk & Schneider, 2002; Mapp & Bergman, 2021; Morris & Nóra, 2024). Relational trust is vital for ensuring that school teams can work collaboratively on a common design even when they bring different positionalities, identities, and experiences. Schools that excel in developing relational trust have been found to use an assets-based lens and draw on funds of knowledge that families bring from their home and communities (Bergman, 2022; Esteban-Guitart & Moll, 2014; González et al., 2005; Mapp et al., 2022). Relational trust between families and schools is informed by feeling a sense of alignment of beliefs on what makes a good-quality education; the more parents/caregivers and teachers feel their input and suggestions are valued, the more they feel they share a common understanding of what a good-quality education looks like (Morris & Nóra, 2024).

The Conversation Starter Tools methodology was used to understand the landscape of family, school, and community engagement in SW PA as part of the development of the design sprint process. The Conversation Starter Tools are participatory and community-driven, using a mixed-methods approach of surveys and intentional conversations to understand beliefs on education and experiences in and with family engagement (Morris et al., 2024). Surveys were used to capture families’ and educators’ beliefs on school and levels of trust alongside the different opportunities and barriers for engagement. Beliefs, barriers, and opportunities for engagement and levels of trust were analyzed by demographic groups, including families’ levels of education and socioeconomic status, gender, race, and the age of children, among others (see Appendix A for details on the Conversation Starter Tools methodology and Appendix B for highlights from this research in SW PA).

3. Design Sprint Process

The design sprint process involves five key fluid and iterative steps that are refined each year by the collaborative:

Step One: Understand the family, school, and community partnership landscape. In the design sprint process, schools can formally conduct Conversation Starter Tools research with their families and educators (and students for middle or high schools) prior to beginning the process. They can also choose to use some of the key questions during their workshops, as outlined in Box 1 below. For example, families and educators share their beliefs on the purpose of school through an informal real-time survey and then discuss their beliefs through critical dialogues during the design workshops detailed in Step 2.

Box 1. Survey and critical dialogues on the purpose of school.

Objective: To understand families’ and educators’ beliefs on the purpose of school.

Survey Question: What is the most important purpose of school? (select one only)

- ▪

- To prepare for further education (coded as academic learning)

- ▪

- To develop skills for work (coded as economic learning)

- ▪

- To be active citizens and community members (coded as civic learning)

- ▪

- To understand oneself and develop social skills or values (coded as social and emotional learning)

- ▪

- Other (please enter)

The process: Each school team answers the above question and can use the other CSTs questions as well. They answer the questions either through an all-school survey or an informal, real-time survey in one of the design workshops. For an all-school survey, see the Conversation Starter Tools: A participatory research guide (Morris et al., 2024) for detailed steps of the research process and additional questions. For an informal, real-time survey in the design workshop, each participant answers the question individually, and their response is shown relative to others in the larger workshop using a digital or other survey tool. In small groups with 8–10 family and educator representatives, workshop participants describe how and why they chose their top purpose. For example, if they chose “to be active citizens and community members”, they describe why they named this as a key purpose and what was behind their thinking. A large group debrief on the different ways that participants responded, and where they were aligned or varied in perspectives, helps ensure that the design hacks consider the multiple purposes of school and different viewpoints.

Step Two: Build a community of practice in and between schools. Participation in the design sprint process is extended to all families and educators in a school. Efforts are made to ensure school teams are inclusive of families not already involved in other activities and who come from diverse gender, racial, socioeconomic, linguistic, and other backgrounds. Each team conducts empathy interviews with others in their community to understand their lived experiences with school and to understand the barriers and assets in their communities. As outlined in Box 2 below, during these empathy interviews, educators listen to families and families listen to educators. School teams then participate in a series of design workshops where they discuss the barriers to family, school, and community partnerships and choose assets to focus on. For example, the team in the first case study identified their assets as “hometown love, connectability, and a no-quit attitude”.

Box 2. Empathy interviews.

Objective: To gain a deeper understanding of different perspectives (e.g., families of educators and educators of families).

The process: School teams lead these interviews in their communities and determine how many interviews they will conduct (each team member conducts at least one). Ideally, these interviews take place in person at a place where the interviewer and interviewee feel comfortable, such as a community center, café, or school playground. School teams work together to finalize the questions they will use in the empathy interviews.

Illustrative questions:

- (Getting acquainted) Can you tell me little about yourself and your connection to the school community? (encourage educators to share their journey in getting there; encourage families to share a little bit about their family).

- (Experience as a learner) Thinking back to your own experience as a student in school, how would you describe your experience?

- (Definitions of and types of family engagement as well as barriers) What does family engagement mean to you, what should it look like? What do you believe are some of our school’s strengths when it comes to engaging families? What do you believe are some of our school’s challenges when it comes to engaging families?

- (Aspirations and visions) What are some hopes and wishes you have for your students (as a teacher) or your children (as families)?

- (Connections) Can you tell me about a time you had a strong connection with a parent/caregiver (as a teacher) or a teacher (as a parent)? What made it strong?

- (Interactions) Thinking over your typical interactions with families (as a teacher), or educators (as families), how would you describe them (positive, neutral, negative)?

- (Care and community) What is one thing you wish your families (as an educator) or teachers (as a parent/caregiver) could know about you?

- (Trust) What is one thing that families could do to build trust with you (as an educator), or that the school or educators could do to build trust with you (as a parent/caregiver)?

Tips:

- The most important thing is for everyone to feel welcome and heard, take your time.

- Encourage stories.

- Avoid yes/no questions and encourage open-ended responses, asking the speaker to elaborate when appropriate and they feel comfortable.

- Observe body language.

- Allow for silence as people are processing.

- Listen and avoid interjecting with your own stories.

- Take notes so you can ask follow ups (and share some of your learnings with teams).

Analysis: School teams are encouraged to take notes and share their empathy interview learnings with each other. The Partnership does not typically record the conversations to ensure everyone feels comfortable. As teams share what they have learned, they can look for commonalities across interviews and begin thinking about a mini-design (or design hack) to test that will encourage deeper family and school engagement based on the ideas that emerged. Teams can choose if they want to do a more formal analysis with the interview data, but this should be communicated to participants from the start and follow appropriate protocols.

Step Three: Create and try out a design. School teams participate in a series of design sprint workshops with the intention of creating an activity or practice, or design hack, which responds to the opportunities for and barriers to partnerships identified in Step One. The design hack is a tool in human-centered design for centering families, students, and educators in the process of inspiration, ideation, and implementation (IDEO, 2020; Landry, 2020). Before developing the full design hack, teams try out a mini-design-hack to give them the skills, confidence, and momentum for the larger design, as described in Box 3. For example, the school team in Case Study Two analyzed their kindergarten registration forms to learn what home languages children spoke at home to ensure their school communication was always conducted in these languages going forward. In the larger design hack, the team built a regular practice that recognizes and honors the diverse home languages spoken among their students and families (Rayworth, 2022).

Box 3. Mini-design-hack workshop.

Objective: To generate and test ideas that support the team’s vision of family and school engagement. Performing a mini-hack that is low-cost and quick builds the confidence of the team before they try out a bigger design hack.

Process: School teams generate a list of possible ideas that will help them reach their aspired vision of family and school engagement, drawing on ideas from the empathy interviews and critical dialogues. They chose one of the ideas to test in a mini-hack. A mini-hack has the following characteristics. It is:

- Quick. It can be tried in just a few days.

- Small-scale.

- Low-cost.

- Aligned to the family and school engagement vision.

- Innovative (trying something new).

- Attempting to uncover an unmet need.

The impact of a mini-hack can be big. For example, one school team wanted to learn more about the families in a particular community in the district, as the educators felt they did not know them well. The team decided to host “donuts at the bus stop”, where educators and families had informal conversations with the families. This enabled them to have a casual conversation and meet parents/caregivers face to face in an informal but comfortable environment. After the mini-hack, the different teams came together across schools to discuss what they learned collectively.

Step Four: Refine the design. After trying out their mini-hack, teams meet with other schools to share their learnings, assess how the design responds to the barriers and needs, and consider how the design addresses equity and inclusion. They use these data and this reflection to refine the design as detailed in Box 4 below. For example, the school leaders and families in Case Study One recognized during the mini--hack that boys were disproportionately receiving interventions for their behavior or academic performance (interview with school leader, 13 September 2022). The school team decided on a restorative practice for boys as their larger design.

Box 4. Individual and group reflection: The Pause, Peer, Pivot.

Objective: To guide school teams in reflecting on their designs and identifying where to make changes.

Process: The individual and group reflection used the Pause, Peer, Pivot approach.

School teams start with pause and reflecton how things went. They answer three questions individually and then discuss responses as a team:

- How would you rate the success of your hack? Why?

- Were you able to move 10% toward your aspirational goal? How did it feel along the way?

- To what degree have you progressed towards building trust in your community and why?

As a group, teams reflect on what kind of information they used to answer these questions (e.g., verbal feedback or something they observed) and what they learned along the way (e.g., common interests with other families).

Peers: Teams then talk to critical peers on other school teams, and together they refine and advance their respective designs. Critical peers may share three kinds of feedback:

- I like… (what worked)

- I wonder… (what needs to be further developed or what is missing)

- I have… (what resources, inspiration, or other ideas that emerged)

For example, in a mini-hack where families and educators sat around a firepit to talk about family and school engagement, a critical peer wondered if this kind of small-group conversation would make families who are introverted uncomfortable or those who do not speak English fluently feel less welcome.

Pivot: Finally, teams think about how to improve their hack or pivot in a new direction with a different design. Teams may ask themselves the following:

- Where should we modify the design or change course?

- What do we hope to see come out of the hacks (e.g., what kinds of changes in mindset or behaviors of educators and families)?

- What elements of the hack may be sustainable year-to-year?

School teams can think about some of the different aspects they could change to seek new perspectives and bring their vision closer to fruition. Teams can decide to reflect on one or all of the following aspects:

- Space (e.g., finding a neutral space that is not at a school).

- Schedule (e.g., if evening is not working, trying the morning).

- Process (e.g., working backwards by starting with the vision and then figuring out the steps to get there).

- Incentive (e.g., giving families an award or tickets to a show for their collaboration).

- Ritual (e.g., building a design hack into an already scheduled ritual like a popular sports tournament or theater performance).

- Role (e.g., encouraging a different parent/caregiver to take charge).

- New approach (e.g., trying a new type of event).

- Communication (e.g., sending a personalize postcard instead of an email).

Step Five: Reflect on the designs. Data collection throughout the process is continuous, community-led, and participatory. School teams check in with each other monthly, and they meet periodically across schools with the support and mentorship of their community organization collaborators. During each of these meetings, there are individual and group reflection exercises. As described in Box 5, at the end of the process, the final design hacks are highlighted in a showcase event where school teams present their journey map of what they learned along the way and where they hope to go.

Box 5. Creating a journey map.

Objective: To document teams’ design sprint processes and to share learnings, growth, and how trust was built along the way. The journey maps help other schools and teams learn from the journeys of their peers.

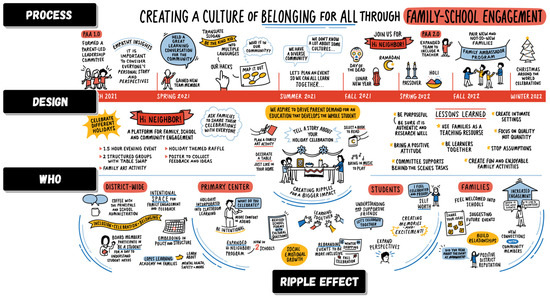

Process: School teams map out three areas: (1) their process along a timeline with key moments; (2) the design; and (3) who they engaged as well as the ripple effect (shifts and changes) among these groups. The teams also draw on empathy interview notes, photos, videos, and other articles from their process to reflect on their journey; teams are encouraged to take photos or videos to capture “aha moments” where they witnessed or learned something along the way. Below is an example of how teams turned their journey into an image.

The journey map example below is a mini-hack from Case Study 2 when the school team wanted to identify the languages spoken at home. They used kindergarten registration forms to identify the diversity of languages spoken among families. They then designed the guiding slogan #bethekindkid, which was translated into all of the respective languages and placed throughout the school to acknowledge the language diversity of their community. This ultimately led to a bigger design hack idea described in the case study where families of diverse cultures shared their stories and different cultural practices with the larger school community, called the Hi Neighbor event. The reach of the event rippled. It started at the district’s primary school, and interest then spread. The school board wanted to participate and to share the design with the larger community. Now, the design is a regular event.

An example of this journey map is presented in Figure 1 below. Findings across the schools are shared with the larger SW PA community and public to inform wider practitioner and decision-making audiences.

Figure 1.

Journey map example.

4. Case Studies

During the 2022–2023 school year, twenty-two school teams from eight counties in SW PA participated in the design sprint process. These school districts service roughly 50,000 students, 52 percent of whom are eligible for free and reduced lunch (Pennsylvania Department of Education [PDE], 2019–2020). Four of the districts are classified as towns, fifteen as large suburbs, and three as rural communities (PDE, 2018–2019). Roughly 9.3 percent of students identify as Black or African American, 3.0 percent as Asian, 2.8 percent as Hispanic in origin, less than 1 percent as Native American or Hawaiian, 6.5 percent as multiracial, and 78.4 percent as White (PDE, 2021–2022). Teachers’ racial demographics across these districts were not readily available, but a study conducted in Allegheny County, one of the largest counties in the area, found that only 4.5 percent of the county’s teachers identified as teachers of color and that there was a decline in the number and percentage of Black teachers (Research for Action, 2022).

The following three case studies were selected to demonstrate how school teams turned documented barriers into opportunities and built assets-based approaches to build partnerships with families. The first case study looks at York Heights, a primary school serving rural and suburban families. In this school, 84 percent of students receive free and reduced lunches, and 28 percent of students identify as Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC) (PDE, 2019–2020). The design hack, intergenerational basketball, was a restorative practice to support third- to fifth-grade boys who were experiencing behavioral and academic challenges in school. The activity connected boys to male adults/father figures in a fun, safe, and supportive environment where boys could express their emotions and build positive social relationships.

The second case study takes place in a suburban primary school, Arlington, where a low percentage of students (14 percent) are eligible for free and reduced lunches. The population consists largely of White households (89.5 percent) who have lived in Arlington for generations; however, the community is shifting in demographics with a marked increase in families who have newly immigrated to the community. Their design sprint focused on elevating cultural diversity and promoting the inclusion of newcomer families by centering families as assets and storytellers.

The third case study, Coalridge, is a rural middle school that serves families from across three primary schools. In this middle school, 97 percent of students are eligible for free and reduced lunches, and 31.3 percent of students identify as BIPOC. Each of the feeder primary schools is situated in a distinct community, with differing socioeconomic and racial demographics. Coalridge’s design hack focused on building community across families in the different communities and addressing gender, cultural, racial, and/or economic barriers to family, school, and community engagement.

4.1. Case Study One: York Heights Primary School

Although York Heights, a town of approximately 6000 people, is designated in the census as a large suburb 30 miles outside Pittsburgh, the school serves a large number of families from rural communities outside the central town (PDE, 2018–2019). The school receives Title One funding, or federal funds that supplement local and state funding to improve educational opportunities for children living in high-poverty districts (Carmichael, 1997). In this school, 8.7 percent of students identified as Black or African American, 3.3 percent as Hispanic in origin, 16.0 percent as multiracial, and 72.0 percent as White (PDE, 2021–2022).

York Heights has participated in the design sprint process over four school years (2021–2025). During the 2022–2023 school year, there were three parents/caregivers and two school staff on the school team. During the empathy interviews, the school team identified three things: (a) families have competing needs and limited time and energy to commit to engagement; (b) the lack of regular and positive communication between families and teachers is a barrier to trust; and (c) there are few points of engagement with families outside of events. During the empathy interviews, parents/caregivers noted that family engagement was particularly difficult for single parents juggling multiple demands and that there were few intentional opportunities to engage families whose children were struggling academically and socially in schools. The school leaders and teachers reflected on which students had behavioral incidences and needed more positive engagement with peers and saw a direct need to support boys. The team identified that there were few opportunities for boys to talk about their emotions in constructive and supportive spaces at the school. One of the school staff, who attended the school as a child, came up with the idea of creating a community of support around basketball, a space that helped boys release emotions in a supportive environment. The school gym was underutilized, available, and a neutral space where parents, mentors, and boys could meet after school.

In addition to recognizing the boys’ needs, during the empathy interviews, parents/caregivers—and especially fathers—described their own traumatic experiences with schools and noted how family engagement spaces rarely felt inclusive of them as men. The school team wanted to demonstrate how fathers are important assets in building family and school partnerships and designed a hack where boys could spend time with male family members or mentors to shoot baskets and talk. They intentionally invited 15 boys from diverse backgrounds and family structures experiencing behavioral or academic challenges alongside their accompanying adults. Roughly a third of the boys identified as White, a third as Black, and a third as mixed race. Throughout the roughly five-month process, the boys met five times and had unstructured time to talk about topics such as divorce, death, academic progress, and any struggles they were experiencing, as well as peer relationships. Boys were given the agency to control their conversations and to choose what and when they shared. Mentors were in close communication with the boys’ mothers in households without a male caregiver to participate.

Although this design hack was only implemented over the course of one school year, it was a way for the school to try a more restorative and family-centric approach. The school team learned that being intentional in reaching families and students who are least likely to participate in regular school events was key. They identified a critical need to bring families into the school, to mobilize low-cost resources, and to collectively design a solution. The boys’ well-being was at the center of their design. Parents/caregivers who wanted to be more involved with the boys and to have spaces to connect with the boys were identified as a critical asset, as was the underutilized gym space that was available at no cost. The common love of basketball served as a medium through which the boys and adults could come together and where the young men could share their emotions, frustrations, and joys.

While the design hack emerged from a need identified through the data and by the school team, their approach builds on masculinity research, which posits that boys often do not have sufficient spaces in schools dedicated to their well-being (Noguera, 2003; Reeves, 2022; Reichert & Kuriloff, 2004). Giving boys a safe space to communicate their emotions and experiences with families and adults in a school setting supports their social and emotional development as well as their academic progress (Noguera, 2003; Pérez-Gualdrón et al., 2016). These spaces are especially critical for boys who are marginalized racially, economically, by disability, and by other forms of discrimination and exclusion (Pérez-Gualdrón et al., 2016; Rios, 2011). Creating positive opportunities in schools for fathers and mentors to participate in the boys’ lives helps close the gap between school and family. As one parent stated, “nowadays in order for you to find out anything that’s going on with your child in the school, you have to participate” (Human Habits, n.d.). This design hack gave the boys’ fathers or mentors a chance to (re)engage with schools in a way that focused on their child’s well-being and relationships. As one participating parent described of the design sprint, “I think it normalizes a dad and a son spending time together” (Human Habits, n.d.). The parents/caregivers and mentors benefitted as much as the boys. As one mentor said, “I’m enjoying it probably more than he is” (Human Habits, n.d.). The York Heights school team created a safe space and whet the appetite for more activities focused on student well-being. The team received funding to keep this program going.

4.2. Case Study Two: Arlington Primary School

Arlington Primary School is located in a large suburb roughly 10 miles from Pittsburgh (PDE, 2018–2019). Of the students in the district, 14 percent receive free and reduced lunch (PDE, 2019–2020). The district receives Title One funding as a Targeted Assistance Program for select students. Among the students, 2.0 percent identify as Black or African American, 2.3 percent as Asian, 2.0 percent as Hispanic in origin, 4.2 percent as multiracial, and 89.5 percent as White (PDE, 2021–2022). The county where the school is located has experienced notable demographic shifts in the last decade with residents who identified as Asian increasing by nearly 72 percent, those who identified as Hispanic in origin increasing by 80 percent, and those identifying as multiracial increasing by 190 percent (University of Pittsburgh, Center for Social & Urban Research, 2021).

During the 2022–2023 school year, there were four parents, one teacher, and one school leader on the school team. One theme that emerged during the kickoff meeting and the empathy interview process was the need to create welcoming schools for all families to reflect the increased cultural and linguistic diversity in the district (interview with parent, 31 October 2022). The school team aspired to use a familycentric approach that “develops the whole student”. During the empathy interviews, teachers and families elaborated on their hopes and visions for this aspiration. They wanted to create culturally relevant opportunities that value and honor the homelife cultures in the classroom and school (Ladson-Billings, 2009). As families and school educators described in follow-up interviews, while the district population is still predominantly White families who have lived in the community for generations, newcomer families bring rich cultural and linguistic contributions. This knowledge and experience was seen as an asset by both families and teachers and an opportunity for the school community to intentionally center the experiences of newcomer families and to mutually learn from each other and build communication and trust. Opening schools to be inclusive and welcoming of families of different cultural, language, and religious backgrounds was the core of the design hack. School staff also noted that preventing the bullying of children based on cultural and language backgrounds was a critical objective of their design.

In interviews, a parent whose family had migrated to the US from Latin America described how her aspirations for the school were to have greater ease in approaching teachers and that parents/caregivers who do not speak English as their first language should feel welcomed and able to communicate with schools (interview with parent, 31 October 2022). She wanted her child’s culture to be seen as a fund of knowledge in the classroom. One of the school staff who grew up in the school community wanted the team to create more authentic connections and to move beyond using sports as the sole mechanism for fostering engagement. This staff member also wanted to understand students’ and families’ cultural backgrounds so she could make sure that curriculum, materials, and school approaches reflected their varied experiences.

The Arlington team centered their design around elevating the cultural assets of newcomer families within the district. Instead of just planning their usual history month practice (e.g., National Hispanic Heritage Month) where artists are invited to perform and teachers read books representing different cultures, the team wanted to center sharing and teaching around families’ experiences. They wanted families to decide what they wanted to share and for the school community to see and value their fellow neighbors and their cultural knowledge. This desire fueled the development of an event at the start of each school year, which has become regular practice. While schools across the US host similar events, Arlington moved beyond celebrating diversity through a one-off event to connecting learning to the classrooms and building a culture of honoring funds of knowledge and families’ stories in their school. In a time of deep social, cultural, and political divisions across their region, the team decided to lean into building unity.

At the first event, all families were invited to listen to three families share the history of cultural celebrations in their homes and communities. One family shared their experience of Día de los Muertos, the “Day of the Dead”, celebrated across Mexico and Latin America and among Chicano communities in the US, to remember beloved family members. Another family shared the traditions of the Ramadan month of fasting, one of five pillars in Islam and when communities focus on prayer, gratitude, and charity. The third family told stories about the Lunar New Year and how communities across East Asia celebrate the lunar cycle. Dialogues with families and teachers were intentionally built into the events. Families and educators were given space at the event to listen, share, and exchange their own experiences after a presentation by the featured families. Teachers created art activities and identified stories to complement the different celebrations in their classrooms. As one of the parents noted, participating was affirming but also not enough as more efforts to integrate families’ funds of knowledge into the classroom are needed (interview with parent, 31 October 2022).

Through the process, the Arlington school team identified what they could do to make the learning environment more culturally relevant and responsive and to deepen their approach to centering families. They also identified a need to shift the mindset in their community to one that saw the multilingualism of families as an asset to the school as opposed to positioning families who do not speak English at home as deficits. The team created their event to focus less on telling families what students were doing but instead on listening to families’ experiences. They pivoted from teachers inviting families into the school community to families inviting teachers and other parents/caregivers to see and hear their families. This approach builds on the culturally relevant pedagogy, as developed by Ladson-Billings (2009), and culturally responsive pedagogy by Gay (2018). Culturally relevant and responsive pedagogies position culture as a powerful tool and force in shaping how students and educators see themselves and their world and assert that classrooms and teaching should be responsive to these different cultures. Culturally relevant approaches in school affirm students’ histories, cultures, and identities and are an important bridge for forging relationships between the school and home (Ladson-Billings, 2009). Enacting culturally relevant and responsive approaches was not just affirming for families who shared at the event but also for other families who did not feel seen. One parent spoke about her child’s experience in a two-mother home, “A lot of time there is talk about dads in the classroom or families in the classroom, but that doesn’t always reflect our family. I think it’s important for teachers to take the time to really get to understand the children in their classroom and what their family life looks like, so that they can better incorporate those different types of families in the lessons that they’re teaching” (Kidsburgh, 2022a). Centering different cultures in the school helped families feel acknowledged and heard, and that they belonged.

When reflecting on what was learned, the school team talked about leading from the desire to support all students and families to thrive and not out of fear that efforts would stir controversy. As the team was creating their design hack, polarization within their state and country continued to increase around them (Cohen, 2021). Yet, the COVID-19 pandemic presented an opportunity to work more intentionally with families. As one educator noted, “Covid helped us see that families wanted to connect with educational communities. This was not a reason to be scared of families, this was perfect timing. There was inquisitive energy (who is doing what, when, and how)” (interview with school leader, 15 September 2022). Authentically and intentionally talking about culture in their school is an ongoing process, but the team has started to lay the groundwork and has expanded the practice to the middle school in the district where students are curating their own version of the design hack. The Arlington school leaders have learned the importance of creating positive opportunities to connect with families. As one school leader noted, “People need to feel like they can try new things, teachers and parents alike… we are trying to build a strong community as we recognize that children can do well when they have a collective community behind them” (interview with school leader, 15 September 2022). As both education leaders and families noted, whether it is families with small children, those new to the community, or families struggling to connect with the school, there was a need to bring families together and help each other develop a sense of belonging. The team wanted families to feel that they were a valued part of a learning community ecosystem that embraced change.

4.3. Case Study Three: Coalridge Middle School

Coalridge Middle School lies in a rural town of less than 7000 people located about 20 miles outside Pittsburgh. The district receives Title One funding, and roughly 39 percent of the students receive free and reduced lunch (PDE, 2019–2020). Among the students, 17.1 percent identify as Black or African American, 0.7 percent as Asian, 3.4 percent as Hispanic in origin, 7.6 percent as multiracial, and 71.2 percent as White (PDE, 2021–2022). Three primary schools feed into the Coalridge Middle School, each with different demographics, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of the primary schools feeding into Coalridge Middle School.

Coalridge Middle School is situated in the middle-income community near Primary School 2 and is roughly 20 min from the predominantly low-income and BIPOC community near Primary School 3. The majority of the teachers at the middle school live close to the first or second school in the middle- or higher-income communities. The school leader in this research was not from the area originally but lives near Primary School 3 in the predominantly BIPOC community. He was the first Black administrator at Coalridge Middle School.

Coalridge joined the Partnership in 2022–2023 with three parents/caregivers and two teachers and school leaders on the school team. Families from the low-income community could only reach the middle school by car or taxi, not by public bus. Because of transportation barriers, families from the lower-income community were less likely to attend events and activities held at the middle school. To the dismay of the school team, some families from the more affluent communities expressed to educators that they did not want their children to go to school with kids from the lower-income community,. In conversations and empathy interviews, families and educators alike said they wanted to build a school community across the different geographies and demographics. The school team set their goal to “build opportunities for collaboration between diverse families, educators, and administrators to support students’ learning and well-being”.

Coalridge’s design hack was a community-building event outside the school walls intended to bring families of different socioeconomic backgrounds, races, and communities together to build positive and trusting relationships. The school team wanted to plant and cultivate a culture of inclusion and welcoming, especially for historically marginalized families from the lower-income community. As noted in the research, school leaders and teachers often reproduce the idea that families are hard to reach, but in reality, it is often schools that are hard to reach (Crozier & Davies, 2007). This was the case in Coalridge, and the team decided to host their event close to the homes of families who struggled to get to the middle school, near Primary School 3. They chose a space frequented by families of all racial and socioeconomic backgrounds, the football field. The school team created a family, school, and community tailgate party before one of the biggest football games of the year. They chose an event where families and educators would be excited to attend and where they could build authentic connections that did not focus on student grades, behaviors, and other sources of stress for families. This pre-game event had record-breaking attendance for the school, and families engaged in eating, impromptu dancing, and talking with each other. Not all families stayed for the game, but they expressed appreciation for having a school event that was closer to home and both fun and inclusive. Given the success of this event, the school team organized subsequent events outside of the school that brought the three communities together.

One of the lessons learned through the design sprint process was that forming solidarities to build a more welcoming and inclusive environment is critical, as is intentionally addressing racial and socioeconomic barriers to inclusion. Teachers and school staff worked very closely with the families in the design, and there was a deep respect and care built within the team. Building relational trust does not happen at one tailgate event, but it can shift over time with intentional and equity-oriented design, dialogue, and trust between families and schools (Barajas-López & Ishimaru, 2020; Mapp & Bergman, 2021). As a parent leader reflected, it is important to “create more opportunities to build trust amongst diverse voices and sustain the momentum from the success of the tailgate” (interview with parent, 22 April 2023).

Another lesson learned by the Coalridge team was that engaging the families of middle school students requires a slightly different family-centric approach than efforts to engage the families of primary school students. Research shows that the types of family engagement and beliefs about school can and do change depending on the age of students, with the engagement of families getting more difficult as children grow and want their families to be less involved in their schooling (Hornby & Lafaele, 2011; Morris & Nóra, 2024). The Coalridge team therefore acknowledged the students’ perspectives and voices, and the school leaders intentionally engaged with students daily to understand their ideas and aspirations for family and school partnerships. As the school leader noted, “Starting with the kids, [building trust with them] really laid the foundation….it gets parents to go ‘okay, well if they trust you, we trust you.’” (interview with school leader, 14 April 2023). Building this trust with students allowed teachers and school leaders to build trust with families (Rodela & Bertrand, 2021). Trust started with caring about students, treating them as if their perspectives matter, hearing their ideas, and following through on promises—all the critical elements of relational trust (interview with school leader, 14 April 2023). One of the areas identified for a further design hack is how to be more inclusive of newcomer Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking families joining the school community.

5. Discussion

The design sprint process is built on the premise that collective reflection together with action can lead towards transforming praxis (Freire, 1974). The process is centered on understanding the needs, experiences, barriers, and assets that school teams bring to the process. Teams are given the creative agency, mentorship, and financial support to (re)imagine family, school, and community partnerships through design hacks. They are also given structured opportunities to reflect and engage in ongoing, honest, and supportive critical dialogues with their communities. Across the collective teams, successes and shortcomings encountered in the praxis are examined, and lessons are shared with the wider community.

Four key lessons from the school teams have emerged. First, educators and families alike need to reflect on their family engagement mindset and beliefs at the start of the design sprint process. Radically reimagining family, school, and community partnerships to be familycentric requires an innovative mindset and the ability to openly reflect, critique, and trust. It requires school staff and teachers to examine the extent to which they are involving families by telling them how to participate versus really engaging families and listening to their needs and aspirations (Ferlazzo, 2011). Regular opportunities to brainstorm and discuss as a collective team require deep reflection on behalf of each individual and are essential to building trust in school teams. The design sprint methodology used by the Partnership has continued to evolve and has since been tried in communities in British Colombia, Canada; Doncaster, UK; and Maharashtra, India (Kidsburgh, 2022b).

The second lesson is that developing relational trust between families, schools, and communities requires understanding the landscape and demographics of families and educators as well as identifying clear needs and opportunities in the school community. Reflecting on viewpoints and different experiences through empathy interviews helped school teams hear and see each other and to identify common aspirations for family, school, and community partnerships. The family-centric design sprint process requires banishing deficit narratives and using schools’ and families’ assets and as springboards for innovations. The design process takes time, resources, and mentorship to think outside of the box and to look beyond the ways family engagement has been historically enacted in schools. Teams also need space and humility to try and to fail in their process of (re)imagining. The following has become one of the mottos of the Partnership: developing these relationships must move at the speed of trust. Schools need to move at their own speeds in building this trust (Morris & Nóra, 2024).

The third lesson is that school leaders must hand over power to family and teacher co-leads if they want to truly open schools up to families. As tensions between schools and families escalated in the US during the pandemic and continued to escalate post pandemic (Stelmach, 2020; Winthrop, 2023), giving up this power and control can be daunting for schools and requires teachers, leaders, and parents/caregivers to respect each other’s viewpoints, but it is possible. When school leaders support parents/caregivers to assume roles beyond volunteering at events and raising funds, deep opportunities for family, school, and community partnerships emerge.

Finally, the design sprint process encourages school teams to believe that change is possible and helps teams to build the mindset that fostering trusting relationships between families and schools will help build deep changes. This requires rejecting the idea that families are hard to reach and finding ways to make schools easier to reach (Crozier & Davies, 2007). As witnessed, when school teams change and become more welcoming, school communities take note. The interest in the Partnership has doubled since the first year of implementation. Design sprint teams are setting important examples in their own schools and across the larger communities of schools in the region. Intentionally creating communities to be innovative, trusting, and collaborative builds solidarities within and across schools. It is through greater solidarities in promoting family, school, and community collaboration that education systems can be pushed to be more inclusive, welcoming, and innovative (Bergman, 2022; Parent Teacher Association, n.d.).

6. Conclusions

The family-centric design sprint process is still evolving under the collective guidance of the Partnership’s collaborating organizations and schools. Although most school teams are still proposing events as design hacks instead of pushing a little harder to (re)imagine the status quo of engagement into more sustainable and deep-rooted change, they have started to discuss the pathway to this change. In the next phase of the Partnership, it is hoped that schools will move beyond designing events to building more intentional and meaningful opportunities for families and teachers to connect on their children’s learning and development, including their mental health and well-being. The Partnership is also supporting schools to continue centering equity and critical dialogues, even in a national climate steeped in parents’ rights movements and efforts to silence conversations on racial, ethnic, gender, and other forms of equity. It is through these authentic and intentional connections and alliances that deeper change in education systems can be realized (Mapp & Bergman, 2021).

One of the forces that keeps the Partnership moving forward is a rooted community organization at the helm, Kidsburgh, and a dedicated space where schools can continually engage in evaluation and research to understand what is working and what needs redesign. Kidsburgh has become a known ally for schools and families and has been able to attract reluctant schools to the Partnership by showing teachers and families that their needs and ideas are at the core of the design sprint process. As one of the educators in the Arlington Primary School noted, “When you are going down this path, there is no checklist or cookie cutter that works for every school. A core part of success is having leadership support and giving space to experiment and try things out” (interview with school leader, 15 September 2022). This comment was echoed by a Coalridge educator who said, “there is no checklist for building trust”, but learning across school teams is critical for the growth of schools and communities (interview with school leader, 14 April 2023). Another key element of the Partnership is the passion and dedication of families in engaging with schools, sharing their stories, and pushing for change. It cannot be emphasized enough that these school teams have dedicated deep time, care, and energy to supporting their school communities, their efforts are important, and their stories help propel the field of education forward. Although design sprints are a small step towards the larger goal of ensuring that schools are family-centric and places where families feel a strong sense of belonging and where children are thriving, these incremental, collective steps can lead to (re)imaging family, school, and community partnerships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.M. and Y.-L.C.; Methodology, E.M.M. and Y.-L.C.; Formal analysis, E.M.M. and Y.-L.C.; Investigation, E.M.M. and Y.-L.C.; Resources, E.M.M. and Y.-L.C.; Data curation, E.M.M.; Writing—original draft, E.M.M. and Y.-L.C.; Writing—review & editing, E.M.M. and Y.-L.C.; Project administration, Y.-L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a private foundation that supports communities in Pennsylvania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of HML IRB (protocol code 733TBI20 on 2 June 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the schools that have participated in the design sprint process and are the heart and soul of the Partnership. Thank you to the families and school staff, teachers, and leaders from the three case study teams for sharing their stories. We acknowledge Claire Sukumar and to Lauren Ziegler for their contributions. Many thanks to the other members of the Partnership, Linda Krynski, Melissa Rayworth, Rachel Siegel, Adha Mengis, Emily Marko, Eyal Bergman, Rebecca Winthrop, Laura Nóra, Richaa Hoysala, Akilah Allen, Sophie Partington, Max Lieblich, Crystal Green, Lasse Leponiemi for their collaboration and vision. Thank you to Nina Fairchild for editorial support. This Partnership is made possible through the generous support of a local foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Conversation Starter Tools Methodology

The Conversation Starter Tools (CSTs) methodology and process was developed by the Family, School, and Community Engagement in Education initiative at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution in collaboration with global schools and civil society organizations (see Morris et al., 2024, for a full description of the methodology and Morris & Nóra, 2025, for the validation process and details).

The CSTs include three sets of surveys (for families, students, and educators), focus group discussion questions, and other protocols that schools, districts, and civil society groups can use for conducting participatory research in their communities. The methodology and process supports schools and communities in understanding family, educator, and student experiences with family, school, and community engagement and beliefs on education.

“The CST approach integrates data, dialogues, and directions on how to support stronger partnerships across families, schools, and communities. Data on the beliefs and experiences of families, educators, and students in their communities are collected through low-stakes and exploratory surveys. Survey data are not used to generalize or draw conclusions but rather serve as a springboard for dialogues on beliefs and experiences. Dialogues not only build trust among families, educators, and students but also serve as a vital opportunity to generate strategies and new directions to support greater family, school, and community engagement”.(Morris & Nóra, 2024, p. 8)

There are four key steps in the process, as shown in the figure below.

Figure A1.

Conversation Starter Tools process.

Appendix B. Beliefs on the Purpose of School

The following data were collected in schools in SW PA in collaboration with the Brookings Institution in 2020 (see Winthrop et al., 2021, for complete findings). Families prioritized academic and social and emotional learning as the main purpose of schools; educators prioritized social and emotional learning. The strong emphasis on social and emotional learning across parents/caregivers and teachers may be in part because they felt students needed more social and emotional support during the pandemic.

Table A1.

What is the most important purpose of school? (n = 1700).

Table A1.

What is the most important purpose of school? (n = 1700).

| Academic: “To Prepare for Further Education” | Economic: “To Develop Skills for Work” | Civic: “To Be Active Citizens and Community Members” | Social and Emotional: “To Understand Oneself and Develop Social Skills or Values” | Other | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Families (n = 1400) | 32% | 22.5% | 6.5% | 34% | 5% | 100% |

| Educators (n = 300) | 11% | 26% | 11% | 43% | 9% | 100% |

| Mean | 21.5% | 24.25% | 8.75% | 38.5% | 7% | 100% |

Note: data on families’ and teachers’ beliefs on the purpose of school (Table A2) were previously reported in Winthrop et al. (2021).

Families and educators were also asked what they thought the other group perceived as the most important purpose of school. For example, families were asked what educators prioritized, and educators were asked what they thought families prioritized. Over half of families (53%) thought educators prioritized academic learning when in reality educators prioritized social and emotional learning. Nearly half of educators (42%) thought that families were focused on economic learning when the majority of families actually prioritized social and emotional learning and academic learning. Families and educators alike were off in their perceptions of the other, which confirms the importance of facilitating dialogues between families and schools on beliefs on school.

Table A2.

What do you think other groups perceive as the most important purpose of school? (n = 1582).

Table A2.

What do you think other groups perceive as the most important purpose of school? (n = 1582).

| Academic | Economic | Civic | SEL | Other | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Families (n = 1308) | 53% | 14% | 8% | 20% | 5% | 100% |

| Educators (n = 274) | 28% | 42% | 4% | 18% | 8% | 100% |

References

- Barajas-López, F., & Ishimaru, A. M. (2020). Darles el lugar: A place for nondominant family knowing in educational equity. Urban Education, 55(1), 38–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, E. (2022). Unlocking the ‘how’: Designing family engagement strategies that lead to school success. Learning Heroes. Available online: https://bealearninghero.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Unlocking-The-How-Report.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. L. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, P. H. (1997). Who receives federal title I assistance? Examination of program funding by school poverty rate in New York State. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 19(4), 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G. (2021). How political organizers are channeling parents’ education frustrations. CNN. November 18. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2021/11/17/politics/parents-school-frustration-political-organization/index.html (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Crozier, G., & Davies, J. (2007). Hard to reach parents or hard to reach schools? A discussion of home–school relations, with particular reference to Bangladeshi and Pakistani parents. British Educational Research Journal, 33(3), 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R. B. (2025). IDEO. Charting a bold educational future. Available online: https://www.ideo.com/works/ascend-public-charter-schools (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Epstein, J. L., Sanders, M. G., Sheldon, S. B., Simon, B. S., Salinas, K. C., Jansorn, N. R., Van Voorhis, F. L., Martin, C. S., Thomas, B. G., Greenfeld, M. D., & Hutchins, D. J. (2018). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Guitart, M., & Moll, L. C. (2014). Funds of identity: A new concept based on the funds of knowledge approach. Culture and Psychology, 20(1), 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlazzo, L. (2011). Involvement or engagement? Educational Leadership, 68(8), 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (1974). Education for critical consciousness. Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- González, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hornby, G., & Lafaele, R. (2011). Barriers to parental involvement in education: An explanatory model. Educational Review, 63(1), 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Habits. (n.d.). One on one at new brighton [video]. Kidsburgh. Available online: https://vimeo.com/713910031/f7d620f0ba (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- IDEO. (2020). Codesigning schools toolkit: Equitable learning practices. IDEO. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1_CJhPohf529ERjtcVMlb7H_CaGF9AuiG/view (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Kidsburgh. (2022a). Kidsburgh: Parents as allies overview [video]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=86I3yqMSkl8 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Kidsburgh. (2022b). Parents as Allies: Designing for family engagement, globally and locally. Available online: https://www.kidsburgh.org/parents-as-allies-designing-for-family-engagement-globally-and-locally/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Knapp, J., Zeratsky, J., & Kowitz, B. (2016). Sprint: Solve big problems and test new ideas in just five days. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children. Jossey Bass Education Series. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, L. (2020). What is human-centered design? Harvard business school online. December 15. Available online: https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/what-is-human-centered-design (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Mapp, K. L., & Bergman, E. (2021). Embracing a new normal: Toward a more liberatory approach to family engagement. Carnegie Corporation of New York. Available online: https://media.carnegie.org/filer_public/f6/04/f604e672-1d4b-4dc3-903d-3b619a00cd01/fe_report_fin.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Mapp, K. L., Henderson, A., Cuevas, S., Franco, M., & Ewert, S. (2022). Everyone wins!: The evidence for family-school partnerships and implications for practice. Scholastic. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, E. M., & Nóra, L. (2024). Six global lessons on how family, school, and community engagement can transform education. The Brookings Institution. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Final-Six-Global-Lessons_EN_24June2024_web.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Morris, E. M., & Nóra, L. (2025). Technical report: Six global lessons on how family, school, and community engagement can transform education. The Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, E. M., Nóra, L., & Winthrop, R. (2024). Conversation starter tools: A participatory research guide to building stronger family, school, and community partnerships. The Brookings Institution. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/conversation-starter-tools/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Noguera, P. A. (2003). The trouble with black boys: The role and influence of environmental and cultural factors on the academic performance of African American males. Urban Education, 38(4), 431–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent Teacher Association. (n.d.). National standards for family-school partnerships. Available online: https://www.pta.org/home/run-your-pta/family-school-partnerships (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Pennsylvania Department of Education. (2018–2019). Urban-centric and metro-centric locale codes [data set]. Available online: https://www.education.pa.gov/DataAndReporting/SchoolLocale/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Pennsylvania Department of Education. (2019–2020). 2019 Building data report [data set]. Available online: https://www.education.pa.gov/Teachers%20-%20Administrators/Food-Nutrition/reports/Pages/National-School-Lunch-Program-Reports.aspx (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Pennsylvania Department of Education. (2021–2022). Public school enrollment reports [data set]. Available online: https://www.education.pa.gov/DataAndReporting/Enrollment/Pages/PublicSchEnrReports.aspx (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Pérez-Gualdrón, L., Yeh, C., & Russell, L. (2016). Boys II men: A culturally-responsive school counseling group for urban high school boys of color. Journal of School Counseling, 14(13). [Google Scholar]

- Pushor, D. (2015). Walking alongside: A pedagogy of working with parents and families in Canada. In L. Orland-Barak, & C. Craig (Eds.), International teacher education: Promising pedagogies (pp. 233–251). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. Part B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayworth, M. (2022). How the “Hi Neighbor!” event brought one community together—and could change lives elsewhere, too. Kidsburgh. Available online: https://www.kidsburgh.org/how-the-hi-neighbor-event-brought-one-community-together-and-could-change-lives-elsewhere-too/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Reeves, R. (2022). Of boys and men: Why the modern male is struggling, why it matters, and what to do about it. Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Reichert, M. C., & Kuriloff, P. (2004). Boys’ selves: Identity and anxiety in the looking glass of school life. Teachers College Record, 106(3), 544–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research for Action. (2022). Allegheny county educator diversity project. Available online: https://www.researchforaction.org/project/allegheny-county-educator-diversity-project/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Rios, V. M. (2011). Punished: Policing the lives of black and Latino boys. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodela, K. C., & Bertrand, M. (2021). Collective visioning for equity: Centering youth, family, and community leaders in schoolwide visioning processes. Peabody Journal of Education, 96(4), 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmach, B. (2020). It takes a virus: What can be learned about parent-teacher relations from pandemic realities. Alberta School Councils’ Association. Available online: https://www.albertaschoolcouncils.ca/public/download/files/169642 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- University of Pittsburgh, Center for Social & Urban Research. (2021, August 12). First look at the 2020 decennial census: Pittsburgh region. University of Pittsburgh. Available online: https://ucsur.pitt.edu/perspectives.php?b=20210821103378 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Winthrop, R. (2023, March 14). The dueling parents’ rights proposals in congress: What the evidence says about family-school collaboration. Education Plus Development. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/education-plus-development/2023/03/14/the-dueling-parents-rights-proposals-in-congress-what-the-evidence-says-about-family-school-collaboration/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Winthrop, R., Barton, A., Ershadi, M., & Ziegler, L. (2021). Collaborating to transform and improve education systems: A playbook for family-school engagement. Brookings Institution. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/collaborating-to-transform-and-improve-education-systems-a-playbook-for-family-school-engagement/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Ziegler, L., & Winthrop, R. (2022, April 5). School supplies, critical race theory, and virtual prom: A social listening analysis on US education. Brookings Institution. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/research/school-supplies-critical-race-theory-and-virtual-prom-a-social-listening-analysis-on-us-education/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).