Integrating Mental Health in Curriculum Design: Reflections from a Case Study in Sport, Exercise, and Health Science

Abstract

1. Introduction

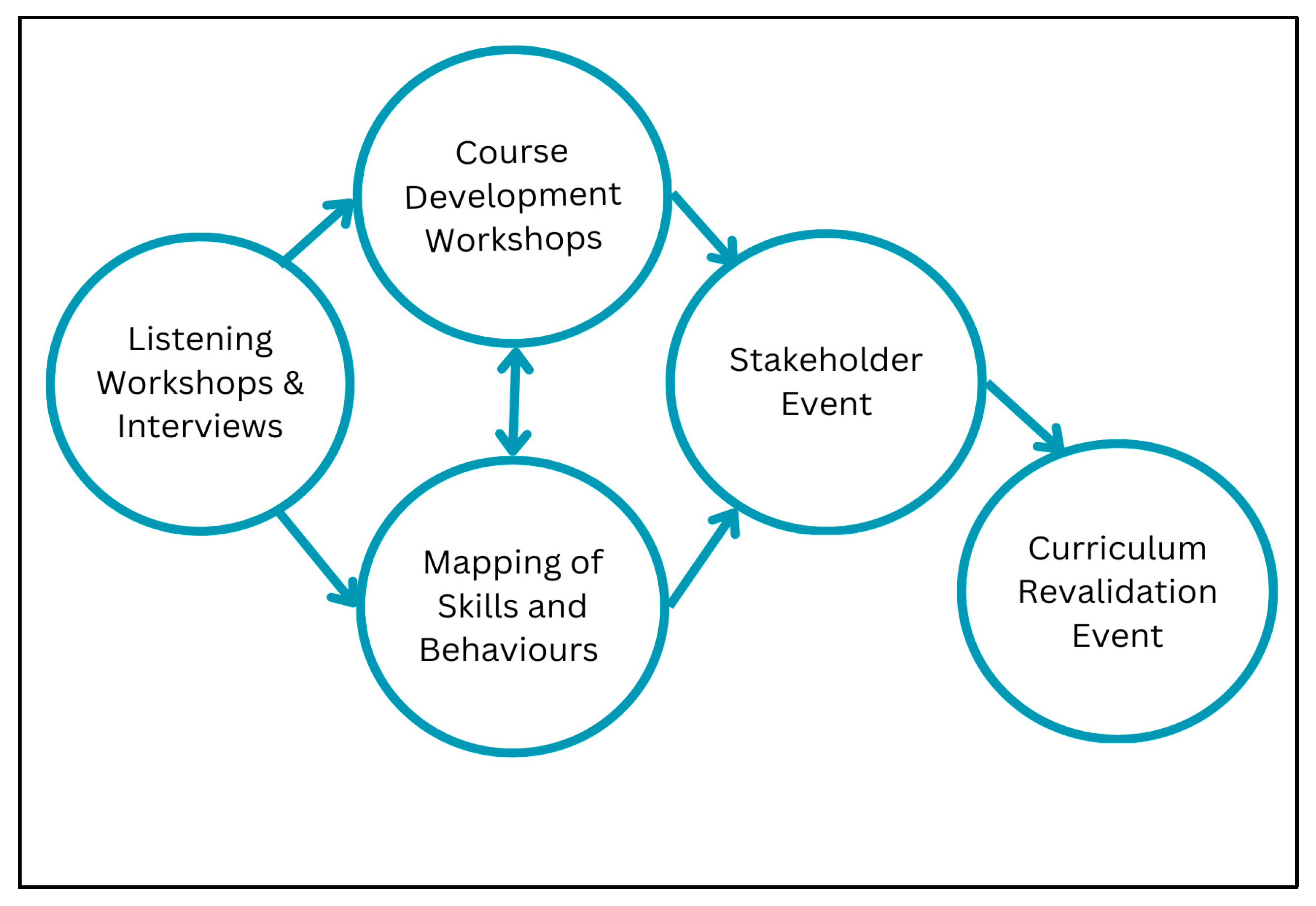

2. Methods

3. Results

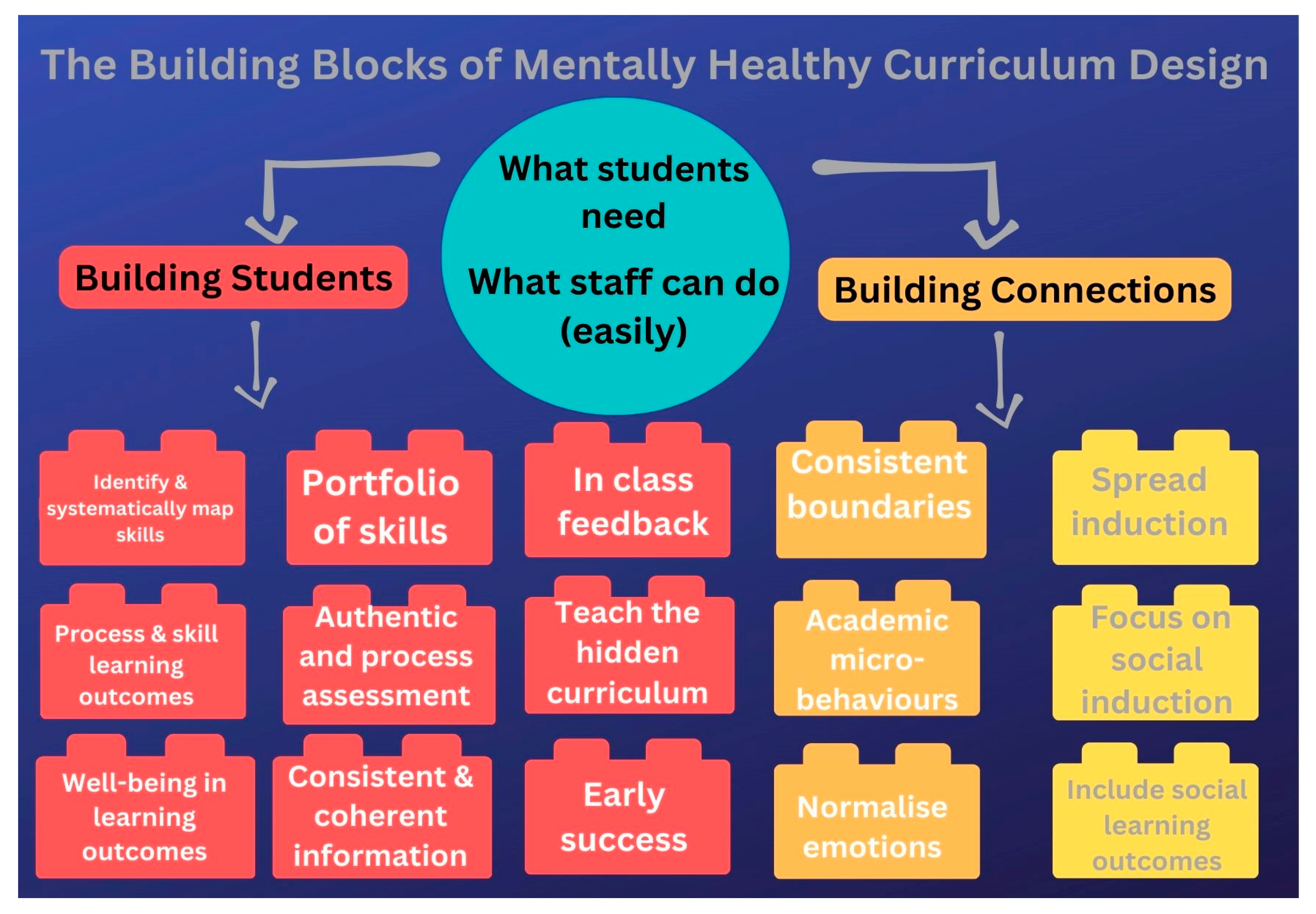

3.1. Building Students

‘This first year is about making sure that if nothing else, you transition into a different way of learning and next step up, which will take some time. That’s one of the reasons why it doesn’t actually count. But you will be learning and we will expect you to engage. And we will expect you to come to us with questions. So we can help you make that transition. It’s almost like seen as a transition year. And I don’t see any reason why that could should be a harmful way to talk about that first year as a way of building relationships, transitioning into a new environment and learning how things operate so that when you go into the second year, you’ve turned those routines into more functional habits’.(Becca, CLT)

‘Lots of students will talk about the fact that they don’t know what’s required of them. And I always find that surprising, because I say, “Well, have you read your module handbook? Because it’ll tell you in there”, and often that there’s a bit of confusion around what a module handbook is, or, you know, stuff that like that. I find it surprising, because I think, why is this not being explained to you’(Jane, Academic)

‘ambiguously worded assignments that students haven’t been properly prepared to talk about. When then students ask perfectly legitimate questions about “how should I go about this?” are then being told, “well, it’s pretty easy to figure that out, you’re at university”. And that’s a classic one we come across actually, They’re thinking that “well, if I help you, then that’s dumbing down or, you know, I’m not stretching you”. But actually, if you don’t know how to go about starting to do something, then you’re just lost. That’s not stretching somebody that’s just abandoning’(James, Academic)

| What we did: Students and stakeholders were involved with the design of the new curriculum. Students will be involved with new material developed for the new validated course. |

‘I’ve heard that be raised multiple times, over recent years, that they’re not prepared when they get to that higher level, that kind of writing is nowhere we expect it to be… Literally, because there hasn’t been enough opportunity to do it’.(David, Academic)

| What we did: We identified learner development skills for the course and shared these with the course team responsible for developing the course and associated modules. Academic staff were asked to consider where these skills could be developed in their modules and embedded into learning outcomes, assignments or classroom tasks. These skills were then mapped across the entire course to show how they developed. These tasks were conducted within the course development workshops |

‘This is about the process and what you learned on the process. I say that a lot. Okay, what happens in your job if you don’t work well together as a team, and you try and make it relevant…It’s always been a hard sell—group work—but maybe the answer is, we evaluate the process. So how well they’re working together as a group, rather than what the end product is purely. So the end product is what the presentation or a written piece of work. Okay, that’s 30%, but actually, we’re going to evaluate on how you work together as a group’(Felicity, CLT)

‘One thing I thought was pointless coming out of a seminar, you know, the ones where they’re like, it’s practical and …we’ll do tests that might be interesting… but you just put it all on a sheet and then you put it in your bag, and you’re probably never going to look for that. Yeah. And I’d rather just spend it getting to know the assessment’.(Simon, student)

| What we did: Replaced some knowledge oriented learning outcomes with process oriented learning outcomes. It was also recommended that academic staff include skill process development within the indicative content of the module specifications and assessments. It is recommended that this is developed across the entire course and not the focus of specific modules. |

They may do like a podcast on it. Or they may do something a bit more creative, something that might be for the public, or for a professional view. So yeah, they do lots and lots of creative type assessments, which, that that to me is authentic assessments what you’re going to actually use in your next job, or how could you use them? Rather than just sitting an exam? Or, you know, writing an essay on something that’s quite abstract?(Pam, CLT)

| What we did: Where possible assessments were designed which were authentic. Furthermore, more detail of assessment type was written into revalidation documents to ensure that authentic assessment is implemented as planned. |

‘We typically will get your 18 year old who’s just coming out of college … if they don’t hand the homework in then there’s a consequence to that they’re held to account. And now coming in, they’re having 12 hours contact time a week. It’s free time. And actually, it’s on there, automatically taking responsibility for their own learning in a new environment, where they’ve never been before. So, it’s finding that balance between holding them accountable in the first week for certain things that they need to do, because that sets up engagement moving forward. But also learning that they do have to… there is that level of independence. And it’s a really hard place’(Felicity, CLT)

‘And just knowing that feeling anxious is normal…and stress and worry will pass and you’ll be alright, it’s gonna be okay. But you just need to practice. If you practice with your peers… I hate doing presentations. But now I’ve learned to love it. Because it’s what I have to do. But it doesn’t mean you don’t worry. You just have to use it to your advantage, being able to teach kids that you can pick up on like, if you’re hot, you’re sweaty, you’re a little bit out of breath, how to manage that with really basic techniques, but then how to use that to your advantage. Because you can use that to your advantage and do well in presentations’(Claire, Well-being)

| What we did: Wrote learner development skills into the course documents including learning outcomes and indicative content. It is also recommended that academic staff are supported in discussing emotions associated with assessments with students. |

3.2. Building Connections

‘Getting people just having fun doing something fun together. Once people can feel at ease with each other and with you guys as the staff team, I think that reduces that that level of distress that a lot of students are probably feeling when they first land. And you can’t learn when you’re in that state, when you’re just a bit overwhelmed by everything. Whereas once you know who your mates are and you can feel safe around people, that’s when the learning can start taking place.’(Helen, CLT)

Steph: That walk was good.

Melissa: Yeah. That was like to share ideas with the younger people and the older people to share ideas. And that was nice and different.

Laura: It was a relaxed setting and not the pressure of like getting something right.

| What we did: Recommended that induction is social focussed. Information on the course and wider university policies to be shared after the initial getting to know you phase. This information should be shared frequently. |

Melissa: Yeah. I think it’s nice when they talk to you about other stuff than just Uni.. You actually think, Oh, they’re actually interested in something than their bit. …

Sophie: When they tell you about the dogs. Yeah. It’s nice to know about them and they know about you so it’s nice to do back.

Laura: Yeah. It’s nice. Like even yesterday in that nutrition and we were on about their marathon.

Melissa: It makes you want to go more if you can be chatty with them rather than sit and listen.

‘example being someone turns up late. It might be because they’ve not been, organized. And that’s immediately we look at when they’ve turned up late. But it is not like they haven’t turned up. So, I congratulated and commended someone for coming in half an hour later to the session. The reason for that was, they had made what I feel was an incredibly brave decision at the start of a new semester. So, knowing the context there, I knew that they would probably not know everyone there. And I said, Thank you so much, you know, I don’t need to know the reasons why you’ve decided to come. It’s not disruptive anything, let’s get on. That person came up to me at the end and said ‘so thank you very much for just making me feel like I can make that call. And I was incredibly nervous and embarrassed coming on’.(David, Academic)

‘They can show care and support by saying, this is something that I’ll be honest, isn’t something that I’m in the best position to help you with. However, there are support mechanisms available. I think that’s the training, I’m thinking of’(Debbie, Well-being)

| What we did: Developing social learning outcomes and indicative content focussed on social connections were promoted. Further academic staff training is required for discussions on emotions and well-being. |

3.3. Recommendations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Binning, K. R., Kaufmann, N., McGreevy, E. M., Fotuhi, O., Chen, S., Marshman, E., Kalender, Z., Limeri, L., Betancur, L., & Singh, C. (2020). Changing social contexts to foster equity in college science courses: An ecological-belonging intervention. Psychological Science, 31(9), 1059–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook: The cognitive domain. David McKay. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, C. A., Hughes, E., Kent, C., Smith, J. R., & Williams, H. T. P. (2019). Student engagement and wellbeing over time at a higher education institution. PLoS ONE, 14(11), e0225770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskreis-Winkler, L., & Fishbach, A. (2022). You think failure is hard? So is learning from it. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(6), 1511–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, C., Armitage, J., Hood, B., & Jelbert, S. (2022). A systematic review of the effect of university positive psychology courses on student psychological wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1023140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, A. M., & Anderson, J. (2017). Embedding mental wellbeing in the curriculum: Maximising success in higher education. Higher Education Academy, 10, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, G., & Spanner, L. (2019). The University Mental Health Charter. Student Minds. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, G., Upsher, R., Nobili, A., Kirkman, A., Wilson, C., Bowers-Brown, T., Foster, J., Bradley, S., & Byrom, N. (2022). Education for Mental Health. Advance HE. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner, P. A., & Hendrick, C. (2020). How learning happens: Seminal works in educational psychology and what they mean in practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Koedinger, K. R., Carvalho, P. F., Liu, R., & McLaughlin, E. A. (2023). An astonishing regularity in student learning rate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(13), e2221311120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubzansky, L. D., Epel, E. S., & Davidson, R. J. (2023). Prosociality should be a public health priority. Nature Human Behaviour, 7, 2051–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArthur, J. (2023). Rethinking authentic assessment: Work, well-being and society. Higher Education, 85, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price Waterhouse Coopers. (2023). Getting in and getting started. Available online: https://www.pwc.co.uk/who-we-are/our-purpose/empowered-people-communities/social-mobility/getting-in-and-getting-started.html (accessed on 10th December 2023).

- Sanders, M. (2023). Student mental health in 2023: Who is struggling and how the situation is changing. Kings College. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, J., & Fishbach, A. (2024). Feeling known predicts relationship satisfaction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 111, 104559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallman, H. M., & King, S. (2016). The learning thermometer: Closing the loop between teaching, learning, wellbeing and support in universities. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 13(5), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Student Minds. (2023). Student minds research briefing. [Online]. Available online: https://www.studentminds.org.uk/uploads/3/7/8/4/3784584/student_minds_insight_briefing_feb23.pdf (accessed on 10th December 2023).

- Studiosity. (2023). UK student wellbeing survey. Red Brick Research. [Online]. Available online: https://www.studiosity.com/hubfs/Studiosity/Downloads/Research/2023%20UK%20Student%20Wellbeing/STUDIOSITY%20UK%20Student%20Wellbeing%20Survey%202023%20(2).pdf (accessed on 10th December 2023).

- Upsher, R., Nobili, A., Hughes, G., & Byrom, N. (2022). A systematic review of interventions embedded in curriculum to improve university student wellbeing. Educational Research Review, 37, 100464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upsher, R., Percy, Z., Cappiello, L., Hughes, G., Oates, J., Nobili, A., Rakow, K., Anaukwu, C., & Foster, J. (2023). Understanding how the university curriculum impacts student wellbeing: A qualitative study. Higher Education, 86, 1213–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worsley, J. D., Pennington, A., & Corcoran, R. (2022). Supporting mental health and wellbeing of university and college students: A systematic review of review-level evidence of interventions. PLoS ONE, 17(7), e0266725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Principle from EMH |

|---|---|---|

| Building students | Academic and student frustrations

| Learning focussed Scaffolded design Learner development Learning focussed Learning focussed Learning focussed Learner development |

| Building connections | Induction Psychological Safety

| Social belonging Social belonging Social belonging Social belonging |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hargreaves, J.; Cooke, B.; McKenna, J. Integrating Mental Health in Curriculum Design: Reflections from a Case Study in Sport, Exercise, and Health Science. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050529

Hargreaves J, Cooke B, McKenna J. Integrating Mental Health in Curriculum Design: Reflections from a Case Study in Sport, Exercise, and Health Science. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050529

Chicago/Turabian StyleHargreaves, Jackie, Belinda Cooke, and Jim McKenna. 2025. "Integrating Mental Health in Curriculum Design: Reflections from a Case Study in Sport, Exercise, and Health Science" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050529

APA StyleHargreaves, J., Cooke, B., & McKenna, J. (2025). Integrating Mental Health in Curriculum Design: Reflections from a Case Study in Sport, Exercise, and Health Science. Education Sciences, 15(5), 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050529