Abstract

The role and responsibility of universities in supporting student mental health has been the subject of high-profile legal debate. Drawing on a thematic analysis of twelve semi-structured focus groups conducted during the Student Minds UK University Mental Health Charter consultations, this paper elucidates the experiences, perceptions, and practices of 75 staff working within student services to support student mental health, with the aim of clarifying the implications for role responsibilities within a whole university approach. Participants described being ‘stretched at both ends’ in response to a significant and ongoing increase both in overall demand and complexity of presentation, further compounded by capacity challenges in public mental health services. Despite the care and commitment of staff, these conditions compromise the effectiveness, safety, and accessibility of university services. As a result, students increasingly present with mental health challenges in academic settings, multiplying risk for themselves, their peers, academic staff, and their universities, whilst negatively impacting the learning process. Thus, precisely as sectoral debate around UK universities’ legal duty of care intensifies, the role and responsibility of university services and academic staff in relation to other institutional and external stakeholders is becoming increasingly indeterminate. Taken together, the findings demonstrate the imperative of clearer conceptualisation and investment in student services alongside closer working relationships with academic staff to ensure student success and safety, and to meet the principles of good practice in the University Mental Health Charter, as advocated by UK government.

1. Introduction

Research literature and discourse across the UK higher education sector have increasingly highlighted concerns about student mental health and wellbeing. Undergraduate students in the UK have reported substantially lower levels of subjective wellbeing, compared with the general population aged 16 to 24, on all four domains (life satisfaction, life worthwhile, happiness, and low anxiety) (ONS, 2020). In some UK-based research, the prevalence and severity of student mental health difficulties have been found to exceed the age-equivalent non-student population (Lewis et al., 2021; Maguire & Cameron, 2021), with evidence of contributing social, academic, and financial factors within the university environment (Duraku et al., 2024). Evidence also shows that UK students report elevated and increasing levels of psychological distress at university, with increasing demand for university mental health services (Broglia et al., 2017), particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic (Bennett et al., 2022; Jia et al., 2021). Indicatively, 61% of UK university counselling services reported an increase in demand of over 25% between 2012 and 2017 (Thorley, 2017), whilst rates of student suicide and self-injury in the UK also increased during the same period (McManus & Gunnell, 2020). Longitudinal data suggest a further increase in cases and service demand following the COVID-19 pandemic (Allen et al., 2023; Jia et al., 2021). Notwithstanding, it is estimated that 75% of students requiring professional support do not access university support services (Macaskill, 2013). Notably, marginalised and minoritized student demographics evidentially experience additional mental health challenges, barriers, and inequalities at university (Stoll et al., 2022), further exacerbated post-COVID-19 (Paton et al., 2023). In addition, students in professional courses such as nursing, medicine, and dentistry report higher psychological distress and risk of suicide (Lewis & Cardwell, 2018), alongside lower help-seeking from university mental health services (Mitchell, 2018; Knipe et al., 2018).

Mental health difficulties at university can have significant individual, institutional, economic, and societal implications (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2021). Students experiencing mental health difficulties in the UK have been shown to be more likely to withdraw from university and to underperform academically, and less likely to progress to higher level employment or postgraduate study (Hughes & Spanner, 2019). There is also a significant financial cost to the institution and potential for reputational damage (Butlin et al., 2017). Conversely, good mental wellbeing at university has been associated with multiple affective and cognitive academic processes and outcomes, including improved concentration, creativity, motivation, problem-solving, and exam performance (Hughes et al., 2022). Beneficial institutional impacts include enhanced recruitment, retention, reputation, productivity, and contribution to key institutional agendas such as equality, safety, diversity, sustainability, and civic engagement (Dooris et al., 2010). Hence, alongside the legal requirement for UK universities to make reasonable adjustments for students with long-term mental health conditions under the 2010 Equality Act, there is “a clear transactional relationship between the core missions of universities and the wellbeing of students and staff” (Hughes & Spanner, 2019, p. 7). As such, support for mental wellbeing delivered in student services has implications for the whole university, including teaching and learning (Hughes, 2021).

Given this, it is unsurprising that universities have long had a role in explicitly supporting student mental health, extending from the post-war years (Crook, 2020). The first university counselling services appeared in the UK, USA, and Australia in the 1950s (Streatfield, 2019; Walker, 1979) and had become ubiquitous by the 1970s (Jacobs, 1979). The interventions developed and provided by university services have been found to be effective in producing both clinical and academic improvement in a UK student population (Broglia et al., 2021; Worsley et al., 2022; McKenzie et al., 2015; Simpson & Ferguson, 2014) and in reducing academic withdrawal (Wallace, 2012). In the UK, these services and interventions have traditionally been provided by student services departments. Whilst student services vary according to the type and size of institution (Rückert, 2015), typically, their role and function, in relation to mental health and wellbeing, entails individual support for those experiencing long-term mental illness, bespoke, time-limited, individual and group student counselling both in person and online; prevention and outreach; consultation with faculty and staff; and risk assessment and management (Prince, 2015). These services are designed to complement mainstream primary and secondary mental health services in the UK, which provide generalist support and needs-based triage for common mental health difficulties and referral-based specialist services, including crisis and urgent care, for severe and enduring difficulties, respectively (Batchelor et al., 2020).

The role of student services is now increasingly positioned within a whole university approach (Universities UK, 2020; WHO, 1986). “A whole university approach means not only providing well-resourced mental health services and interventions, but taking a multi-stranded approach which recognises that all aspects of university life can support and promote mental health and wellbeing” (Hughes & Spanner, 2019, p.10). The University Mental Health Charter provides an evidence informed framework to implement a whole university approach in practice, which has been advocated by UK government (Department for Education, 2024). Within this conception, to be effective, university mental health services must be safe, accessible to all, appropriately resourced, relevant to local context, and well governed (Hughes & Spanner, 2019). This involves consideration of effective working relationships with external partners and the wider university including academic staff, based on clear signposting and common understanding and goals (Hughes, 2021).

However, reported increases in student need, elevated interest from government and the media, external pressures, and shifts in sector discourse have raised new questions about the role of universities and student services (Barkham et al., 2019). These tensions were evinced in the high profile Abrahart v University of Bristol case in the UK. Following a diagnosis of chronic social anxiety, Natasha Abrahart died by suicide in April 2018 on the day of an oral examination. Her parents took the university to court for disability discrimination under the Equality Act 2010, arguing that the university had failed to make reasonable adjustments, breaching its duty of care under the law of negligence. Twenty-five bereaved families, or the LEARN (Lived Experience for Action Right Now) network, further petitioned parliament to create a statutory duty of care for students in higher education (Lewis & Stiebahl, 2024).

Alongside this increased pressure, expectation, and scrutiny on services, the ‘funding of support services… has also not kept pace with the growth in student numbers’ (Macaskill, 2013, p. 5) in the UK, resulting in an ongoing challenge in maintaining effective embedded services (Broglia et al., 2017). Indeed, increasing demand has led to shorter and fewer session allocations, longer waiting periods, and an increase in online provision and referral to private providers (Barden & Caleb, 2019; Mair, 2015). UK students and counselling practitioners have subsequently identified challenges with the accessibility and availability, coordination and communication, and suitability and inclusivity of service provision (Priestley et al., 2021; Cage et al., 2020; Randall & Bewick, 2016). These challenges have been compounded by similar issues related to resourcing and demand within primary and secondary mental health services (British Medical Association, 2024).

Despite high levels of interest in the provision of university mental health services in the UK and internationally, there remains a relative lack of consensus on a number of fronts (Brown, 2018). This uncertainty permeates and obfuscates contemporary political, sectoral and legal debate regarding the role of universities in supporting mental health within a whole university approach. There is a need for greater clarity around the composition and implications of the apparent rise in student presentations to UK student mental health services. Whilst Ecclestone (2020) has argued that this rise indicates an increase in students’ willingness to self-identify as mentally ill, rather than an actual rise in mental illness, comparative evidence using validated measures suggests a genuine deterioration in student mental health symptomology in recent years (Allen et al., 2023; Jia et al., 2021). Furthermore, there is little research documenting how UK university student services are responding to the challenges around the demand and resourcing of student mental health and wellbeing services in practice, in order to maintain safe and effective services for a diverse range of needs (Sampson et al., 2022). Finally, there is also an identified need for further research into the implications of these issues for the wider university system, particularly pertaining to consistent communication and the maintenance of the roles and responsibilities of academic staff (Zile et al., 2024). Given these current gaps in the evidence base, the work reported in this paper sought to bring nuance and light to these questions by exploring the lived reality of student services staff, as they attempt to respond to and support student mental health and wellbeing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

Data are taken from twelve semi-structured focus groups conducted with UK university support service staff during the Student Minds University Mental Health Charter Consultations (Student Minds, n.d.). Focus groups were hosted in-person in Scotland (University of Strathclyde), London (University of Arts), the West Midlands (University of Staffordshire), Wales (University of Cardiff), Yorkshire (University of Leeds), and Northern Ireland (University of Ulster). Participants were recruited from multiple UK universities beyond each host intuition. Each focus group was moderated by an experienced qualitative researcher to ensure inclusivity and focus. Focus groups were semi-structured without a prescribed schedule or topic guide, although facilitation prompts were informed by the aforementioned themes identified in the literature, relating to demand, provision, and partnership working [see Appendix A]. In areas of mental health research in which there is little existing knowledge, qualitative approaches which seek to understand the lived narratives of individual experiences often provide the most profitable research strategy (Palinkas, 2014).

2.2. Participants

Focus groups ranged in size from 3 to 12, with 75 participants in total. Participants were members of university staff that self-identified as student service professionals or as having responsibility for student welfare at UK universities. To understand a range of roles and responsibilities across the university system, no exclusion criteria were specified. Participants were selected to encapsulate a range of experiences and expertise across relevant policy and practice roles within different UK universities, including student service managers (n = 6), counselling service managers (n = 28), counselling practitioners (n = 1), mental health advisors (n = 8), disability advisors (n = 6), wellbeing advisors (n = 14), service administrators (n = 3), student union staff (n = 6) and academic liaisons (n = 3) [see Table 1]. Participants were recruited between January and April 2019 by Student Minds through an extensive network of national and local stakeholders. Each focus group lasted approximately 55 min, providing a total of 655 min, and was audio-recorded and transcribed. Participants provided signed informed consent for their data to be used confidentially and anonymously in the development of the charter and production of associated research documentation. Participants were provided with the opportunity to withdraw their data within one month of data collection without reason or penalty, and signposted to relevant support in their institution to safeguard them from personal or social harm. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Derby Arts Humanities and Education Ethics Committee.

Table 1.

Participant roles.

2.3. Analysis

Two reviewers [GH and MP] initially coded the transcripts separately to inform an inductive reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This involved adherence to the progressive phases of thematic analysis as identified by Braun & Clarke (2006, p. 86) from data immersion, coding, thematic identification, and thematic review, whilst foregrounding “researcher subjectivity, organic and recursive coding processes, and the importance of deep reflection on, and engagement with, data” (Braun & Clarke, 2019, p. 595). The reviewers subsequently conferred to iteratively review similarities and differences in coding structure and synthesise emergent themes. There was broad initial agreement between the reviewers on the salient thematic findings and the focus and scope of the paper. Where differences emerged, conversation continued until consensus was reached through reflexive critical engagement with pre-existing paradigmatic and epistemological or experiential assumptions and expectations; reference to reflective memos; and the clarification of the content and relationship between coding categories within each theme. No findings were discounted due to a lack of consensus. For practical purposes, all data collection was conducted prior to analysis rather than iteratively, though the reoccurrence of thematic identification indicated data saturation had been reached.

3. Results

Taken together, the findings suggest that demand for university support services is increasing across the spectrum of severity. Participants reported a rise in overall demand coupled with a rise in the number of students with complex needs and higher levels of risk. Added to this, a reported rise in thresholds for public mental health services provided by National Health Service [NHS] and Social Care agencies was reported to result in university services becoming the only support available for some students experiencing significant mental illness, characterised by distress and reduced functioning impacting negatively on day to day experience, for which one may have received or be eligible to receive a clinical diagnosis (Hughes & Spanner, 2019). Universities are subsequently ‘stretched at both ends’ as they seek to respond to increasing demand and severity. Notwithstanding, participants emphasised that ‘student services do great work especially considering the NHS’ and that ‘what student services does collectively … [is] one of the fundamental components of the student’s journey … [and] needs to be resourced’ [FG4]. The findings outline participants’ perceptions of how this demand is constituted, the challenges they face as student services staff in delivering accessible, inclusive, and effective services whilst safely managing and preventing risk, the implications for perceived roles and responsibilities, and the responses of universities to these challenges.

3.1. Service Provision

Across the focus groups, participants identified “different levels of services for different severities of mental health presentation” [FG5]. These services could be seen as separate but overlapping strands of support, composed of the following:

- Proactive outreach to the general student population including psychoeducational and lifestyle interventions, and self-help materials.

- General support for student wellbeing through a range of services, not all of which focus on mental health as their primary function, including accommodation services, library services, physical exercise services, financial advice services, spirituality and faith services, and academic services.

- Specialist support for those who begin to experience problems with their mental health such as counselling and psychotherapy services, mental health teams, wellbeing officers and advisors, residential assistants and wardens, pastoral academic officers, peer support, and listening services.

- Specialist support for those with a long-term mental health diagnosis, often funded by Disabled Students’ Allowance, including disability services; mental health practitioners and advisors, specialist mentors and liaison officers.

- Crisis and urgent care for those at immediate risk of harm to themselves and/or others, via the provision of rapid response both during and outside conventional office hours, including crisis case workers, vulnerable student officers, security services, safeguarding officers, and external partnerships with NHS and third-sector crisis services.

3.2. Growth in Demand—Difficulty Meeting Need with Available Resources

Participant experiences unanimously echoed the findings in the literature that there has been a significant and ongoing increase in student need. Within the focus groups, they spoke of a “tsunami of need”.

“In four years our demand doubled and it’s gone up another 30% over the last year”.[FG9]

“The number of students seeing the counselling service now is about 12% of the population and it used to be something like 5%”.[FG2]

“We’re drowning in demand”.[FG5]

This account of increase in demand was perceived to present across the range of the mental health spectrum and represent a genuine expression of student need. Whilst there was some acknowledgement that “there is a huge push of talking about mental health… which is pushing up numbers” [FG10] and “in improving access, reducing stigma, and raising awareness, we have more and more students accessing our services” [FG9], generally participants concurred that the majority of students presenting to services need support and that “students tend not to come to our services until they are in absolute crisis” [FG11]. Therefore, some staff described having “barely seen a student that has come through that door and who is not appropriate for counselling” [FG9].

This experience of growth in demand presented a serious challenge as, in most instances, resources were seen to have not kept pace with demand and in some cases had actually been reduced. There were variations in how this demand–resource gap was expressed, with some participants describing the problem as one of too high a level of demand, while others identified that “lack of resources is the problem, rather than demand” [FG9]. In general though, there was agreement that this gap was real and problematic.

“The budgets are going down and not up [meaning that] the demand is just off the scale in relation to the resource that we have currently to meet it”.[FG2]

“Every year we’re getting more and more and more students, and not really any more staffing … so we can’t meet the demand”.[FG2]

“The sheer number of referrals and students wanting or needing to take up the service doesn’t match the actual staffing of the service”.[FG1]

The composition of this increase in demand was unclear, as participants identified increases in a range of differing presentations from general anxiety to psychosis, with some universities seeing growth in particular presentations, such as eating disorders. However, there was a consensus that the largest rises have been seen in presentations of anxiety.

“Anxiety, without a doubt, is clearly on the rise”.[FG4]

“The two biggest presenting issues we have are anxiety and depression”.[FG10]

3.2.1. Waiting Lists

The impact of the demand–resource gap was highlighted most clearly in the discussion of waiting times and lists. Participants emphasised that the gap made it more challenging to maintain accessible, safe, and effective services. In particular, services highlighted that “any reduction in staffing means that people have to wait slightly longer” [FG2] and therefore, “it can be quite hard to manage the numbers” [FG7] because “we’ve not got enough resource to get through the waiting list” [FG5] or “the capacity to see everybody as quickly” [FG4]. Consequently, given the “sheer volume coming in, the timeframes that students then have to wait to get support is quite long” [FG1] with “a 10-week wait” in one service.

Excessive waiting lists were identified as having significant implications for service accessibility, effectiveness, and safety by discouraging disclosure, exacerbating symptomology, reducing intervention effectiveness, impeding the identification of risk, and ultimately preventing services from providing proactive, preventative, or prolonged care to students. The demand–resource gap was seen to impact both the decision making and behaviour of services and students. Participants described difficult decisions that services have had to face and address.

“If there are more students coming through the door something has got to give, is it the number of sessions or do you have to raise the bar and say, ‘Sorry, you’re not quite unwell enough to come to the services’”.[FG2]

However, increasing service thresholds were seen to prevent opportunities to provide support at the earliest opportunity “which then escalates into withdrawal and non-engagement, which then makes it very difficult to help” [FG12]. These decisions then were also seen to affect the ways in which students engaged with services. Long waiting lists appeared to deter students from approaching services for support or to disengage before services have had the chance to positively impact on the student’s wellbeing.

“Students get annoyed with the service and they think, “I’m not going to bother coming”.[FG2]

Longer waiting times were also perceived to increase risk.

“The wait starts to increase and problems exacerbate quickly, particularly once somebody’s been encouraged to disclose. Then they disclose and if that need is not met, I think, you see things get worse quite quickly, more so than if they were just left to their own virtue, because the expectation of help is evoked and then they’re let down”.[FG9]

3.2.2. Working with Academic Staff

An additional consequence of longer waiting lists appeared to be that staff outside student services were having to absorb some of this need, with potential negative consequences for their wellbeing.

Staff “are affected by what the students told them as well, so its impacting on their mental health”.[FG1]

This phenomenon was discussed in relation to academic staff in particular. Participants reported that students are turning to academic staff for support with their mental health and the responses of academic staff can then, in turn, create additional challenges for student services. This was perceived to happen in two ways. First, some academic staff were seen to be fearful of students disclosing serious mental health problems to them and of not responding adequately when students do present.

“The challenge for student services is the fear amongst academic staff of a student making a disclosure or talking about their mental health”.[FG1]

“[They’ve] become so risk averse and so worried about getting it wrong that as soon as someone cries they’re referred into Student Wellbeing Services”.[FG11]

This fear creates a desire in some academics for an immediately available response that places additional demands on student services.

“A small body of academics seem to think that Student Services will come running with Hi-Vis jackets on like a SWAT team and sort things out, [but] we don’t have the resources”.[FG1]

At the other extreme, participants reported that some academic staff are attempting to cover gaps in support by going beyond the boundaries of their role, which can then contribute to an increase in risk.

“They feel obliged to over help [and] actually that over help can be damaging in terms of timely referrals [and] timely signposting”.[FG5]

”One of the challenges that we have is that some academics are holding too much, and not understanding boundaries, and not letting go… which increases the risk to students”.[FG11]

“They like to hold things themselves because they think they can manage it. Then when it reaches crisis point, then the hot potato comes to us and it’s, ‘Fix it’”[FG1].

In this way, these issues were perceived to compound risk for students, academic staff, and the wider institution.

3.3. Increase in Complexity and Co-Morbidity

Alongside a perception of increasing demand, services also identified “an increase in complex presentation” [FG9] with “needs [that] are complex and multiple” [FG5] and which require more resource-intensive and long-term support.

“There are more and more students presenting with more and more issues and more complex issues”.[FG12]

“We’ve seen a really big increase in people with really high levels of distress and very complex issues”.[FG10]

“Very, very complex at times with multiple presenting needs”.[FG5]

“The whole severity has gone up and very clearly over the past year”.[FG10]

These increasing presentations include long-term mental illnesses, such as psychosis, significant psychological trauma, comorbid presentations and personality disorders.

“There’s an increase in complexity and historical trauma”.[FG11]

“Personality disorders are becoming more and more prevalent”.[FG3]

“A number of people come to university with very complex needs”.[FG3]

The influence of widening participation and changes in student demographics on the presentation of complexity was acknowledged, whereby “people come to university who wouldn’t normally come to university, but then that also increases the chances that more vulnerable people come to university” [FG5], so that increasingly “what we see in universities probably reflects what’s going on out there generally in terms of the presentation of mental health distress” [FG1].

Part of this rise in complexity was a perceived increase in the number of students who were assessed to be at risk from suicide, which increased the challenge to services and staff.

“670 of 1400 referrals have told us that they’ve felt suicidal”.[FG1]

“Our main presentation in health and wellbeing would be students presenting with thoughts about not worth living, thoughts of suicide”.[FG11]

“What a lot of students are telling us is that they’re feeling suicidal”.[FG1]

These presentations did include an increase in more general and milder suicidal ideation but, importantly, participants were clear that they had also seen a rise in more severe presentations.

“The number of students presenting with severe suicidal intent has increased very significantly … we’ve seen particular methods, students rehearsing specific and fatal methods of killing themselves”.[FG10]

Crucially, taken together, it was the combination of a general rise in demand, coupled with the rise in complex presentations and risk that was perceived to put strain on the capacity of services to respond effectively and safely.

“It’s not just about the volume, it’s about the complexity”.[FG3]

3.4. Limitations in NHS and Social Care Support

Compounding the perceived rise in demand, complexity, and risk, was an apparent reduction in the support available for students within the NHS and Social Care. Participants identified that local cuts to health services resources had resulted in increasing thresholds to access these services. As a result, many students who would previously have been able to access specialist care and support were now denied these interventions or were placed on long waiting lists. Student services departments and staff described trying to fill this gap, which added to overall workload, complexity, and risk.

“The cuts on health service have had a huge impact on demand”.[FG4]

“We refer people to really top services in the NHS… the crisis team, when people are really at significant risk, and more and more likely they bounce back to us. So people have committed serious suicide attempts and sometimes they are discharged back to us, in the middle of the night, without any care plan, and that’s really difficult because we’re not equipped for that”.[FG10]

“There are high-risk cases of students that we are carrying whilst they’re waiting for NHS appointments to come through. I think that’s probably one of our biggest concerns”.[FG1]

“Because of the challenges in referring out to specialist secondary services, we’re probably supporting students longer in our internal services. … A referral out would seem a better option, but that isn’t always there”.[FG3]

“The message is always they don’t meet our thresholds for support so therefore they come back to university having had a night in A and E [Accident and Emergency] without any discharge plan or support plan”.[FG4]

In some instances, participants reported that hard-pressed NHS staff were making referrals in the opposite direction—directing students back to the support at their university.

“External health services, if they know the student is supported in university they are much more reluctant to intervene. So they say, “Don’t worry you go to see your counsellor at the university health centre. We won’t put you on the waiting list or we won’t offer you an intervention in the statutory service”.[FG4]

Participants expressed understanding for NHS staff who are making these decisions, recognising that in a competition for scarce resources, students do have more resources to draw upon than many other patients. Their frustration was reserved for the systemic lack of funding that placed them in the position of trying to provide support beyond the function, purpose, or design of their services that result in serious implications for student safety.

“We have seen an increase of the complexity, and although we identify ourselves as working with minimum, low risk, in fact we are working much more with higher risk than we want to but someone has to provide that holding space for the students until they get into services [and] those services also have very much longer waiting times”.[FG10]

“The challenges are the waiting lists and the thresholds for NHS care. We’ve heard site liaison at our local acute hospital say the words, “We will discharge them into the care of the university”. We’re talking about students that are making attempts on their life. In that horrible cycle of making a suicide attempt, they’re judged to have capacity, so they’re discharged, sometimes at any hour of the day, to the care of the university. That’s really misleading and very worrying”.[FG1]

As a consequence of experiencing increasing demand, complexity, and NHS cuts, service staff emphasised the challenge of managing and maintaining student safety and the emotional impact on their own wellbeing. Staff expressed concerns they are holding risk they are not resourced to manage and that this can lead to increased risks to both staff and students.

“It puts a lot of pressure on staff to hold that risk and act as a care coordinator in terms of trying to manage that risk and it is very difficult”.[FG12]

“We’re always five steps behind, at least—then that has terrible consequences… we can’t really do any follow-up and that’s a risk that the student is off out there”.[FG1]

“Those students that fall down the gaps in local NHS provision and more than mild to moderate, but they’re not in crisis… they’re falling through the gap the whole time and it’s really dangerous”.[FG6]

3.5. The Struggle to Define the Role of University Student Services

Across the focus groups, there was ongoing concern and debate as to the appropriate role of student services in the wider system. The challenge of high, complex, and diverse student demand within a challenging resource environment, coupled with the expectations of students, parents, university leadership, government, and a resource-challenged NHS, created an environment in which it was difficult for participants to clearly define the boundaries of their services. Participants identified particular challenges in managing “the expectations of people on universities, be that other services, be that families, or be that students, and the difference between providing an education and a therapeutic environment” [FG3].

“As a university we are not clear enough in stating what we’re able to support and, more importantly, what we’re not able to support”.[FG6]

“What we’re being presented with, we need to have a different approach and a different perspective”.[FG5]

Of particular importance, many participants believed the role student services should play and the role they are having to play, in the current environment, are very different. Some participants suggested that the role of university services is to deliver “embedded services which complement the NHS ones” [FG1] but that in the absence of adequately resourced NHS services, such a model was difficult to maintain.

Some participants advocated a shift towards more proactive, preventative, and universal services that are “very much focused on wellbeing” [FG8] with “rebranding to student wellbeing to try and be more holistic” [FG11] “to change the mindset of both the student and the staff population from counselling being the panacea for everything to wellbeing being the place that you go to refer to and self-refer to” [FG9]. This was situated as part of a “move towards a social and inclusive model where we talk more about emotional wellbeing and emotional fitness rather than mental health” [FG9] because “there’s less stigma” [FG9] and “it’s much less pathologised than mental health” [FG2]. In this capacity, services should “offer mindfulness and loads of different workshops that the whole student population can access so they don’t develop problems”’ [FG10]. By extension, some of these participants advocated a more cohesive and holistic approach to mental health with “much more preventative measures” [FG6] across the whole university system “outside of any kind of wellbeing, counselling or mental health framework” [FG2]. “It’s not just about the patching up services at our end, it’s about the whole ethos of the university and the support within departments” [FG7]. “The burden needs to be shared throughout the whole institution” [FG2].

However, in reaction, some participants were concerned that such a model may undermine the value of professional services, such as counselling, which have a stronger evidence base for their effectiveness. Indeed, some saw the move towards a wellbeing model as potentially undermining professional roles and services that are needed to respond to the complexity of presentations staff were seeing.

“I find myself feeling quite worried about this idea that wellbeing is the answer to everything. There seems to be this opinion that come over time, and I’m hearing it here today, and I’m not dissing your opinions but I just want to express that I find it really worrying that there seems to be lots of ideas that we’re working with a snowflake generation, which I find absolutely abhorrent. That people are going to counselling for every problem when they don’t need to go to counselling. As someone who’s headed up a counselling service for six years and been in the sector for eighteen, I have barely seen a student that has come through that door and who is not appropriate for counselling”.[FG9]

“What scares me is that we’re going to get influenced by a university culture that’s moving more towards business, cutting resources and shrinking thinking space by finding quick solutions. And, actually, we’re going to spend a lot of money ignoring what’s really needed, which is time and space and contact. That really scares me”.[FG9]

“It concerns me that if you’ve got people whose specialism was disability and then you stretch too far in one direction and then other people who are counsellors and they’re doing wellbeing assessments, we’re being inclusive, but we’re all doing everything. And, I think, things fall through the gaps, don’t they?”[FG7]

“It’s important to have the specialisms. I think they still matter”.[FG7]

3.6. Service Efforts to Respond

3.6.1. Triage

Efforts to efficiently and effectively respond to service demand included triaging systems that provide “the stepped-care approach, to make sure that you provide the right volume of support at the right stage of mild, moderate, to severe presentations” [FG1]. Most services had created a non-specialist wellbeing advisor role as an initial and central point of contact, who could assess student need and ensure they could access the most appropriate service.

“Our wellbeing team would often look at students who are possibly in an immediate crisis, and they would deal with, make referrals on, and signpost students onto the appropriate service”.[FG12]

“[It provides] rapid access to immediate advice and signposting’ [and] this allows a rapid response to any student that comes to our triage process … [and] links in very closely with other services that we provide … [either] low intensity faster, shorter, briefer work with students [or] high-intensity services, which are much more traditional, counselling, CBT”.[FG1]

Participants identified that the initial engagement with staff conducting triage could in itself have a positive impact on students, as well as supporting the management of waiting lists.

“Those staff do a bit of containment. … [students] feel that they’ve been heard and they’ve been listened to. Quite often even that one interaction is enough for them, and they don’t need to go on”.[FG9]

Triage also ensures that students are not being added to waiting lists for key services if their presenting issue can be better dealt with elsewhere.

“Two thirds of them get dealt with because they’re practical issues or they just need X, Y or Z. But, then that one third get triaged through to the other services”.[FG9]

However, participants also highlighted risks of the triage system to staff and students. Staff conducting triage are often unqualified and are exposed to significant levels of disclosure, which can have an impact on them. Triage also requires students to disclose more than once, which can in turn become a barrier to engaging with support.

“A student comes to you and spends 20 or 30 min telling you their situation, which is very difficult and traumatising for them, then you have to say, “I’m so sorry, please go and tell somebody else… having to retell their stories, that’s quite daunting and people drop out”.[FG2]

It was also recognised that triage can only provide a snapshot assessment of the student’s presentation at one particular moment.

“Need will change’ [between assessment and treatment] ‘by the time you’ve seen them, it’s actually a very acute need … the greater the gap the larger the risk of that happening”.[FG10]

3.6.2. Peer Support

Participants also identified a desire within universities to utilise peer support more to help address the demand–resource gap.

“We’re trying to cope with demand by doing a lot more educating and the peer-to-peer stuff, trying to plug that gap to be the first response before needing counselling”.[FG2]

However, there were also concerns that peer support schemes contain significant risks for student peers and volunteers, given how much they were being asked to do.

“[I worry about] the vulnerability and impact on student volunteers … their access to support, what we’re asking of them”.[FG3]

“We’ve got students giving a huge amount and actually dealing with a lot of trauma difficulty”.[FG3]

Despite these clearly significant challenges, participants were clear about the value and impact of the work of student services. Many took time to celebrate the contributions and abilities of their colleagues. These accounts partly reflected moves towards the increasing professionalisation of mental health roles with the recruitment of more qualified and experienced mental health staff, who are more able to respond effectively.

“The mindfulness workshops are brilliant... but we have [Name], she used to work for [Organisation], and she facilitates those. They’re brilliant”.[FG11]

“I won’t mention where I’m from, but amazing, amazing team that we’ve got here, brilliant”.[FG1]

“It works effectively… rapid response teams of people who are competent to manage someone who has not interacted, with a set of really complex issues, and can sort of tackle them there and then”, “This is what you can do now, this is what you need to do in the medium term, this is what you need to do long term”, just in a very short space of time”.[FG3]

Participants also reflected on the impact of their services and personal interactions with students. These were reflected in formal measures, student feedback, and staff observations.

“Students typically will tell us it’s a really important resource, and if it hadn’t been there somewhere between a third and a half would have either definitely left or most probably left the university”.[FG7]

“I’ve seen so many students come and make amazing recoveries. And what that recovery means to them is defined by their [circumstance]”.[FG3]

4. Discussion

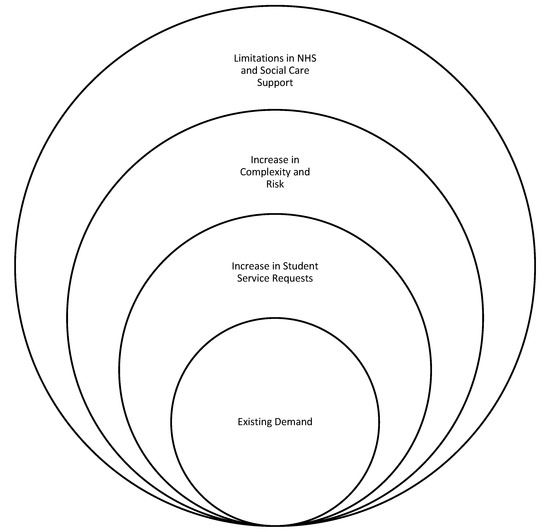

The reported experiences of participants reflect existing evidence demonstrating an increasing, elevated, and persistent demand for university support services across UK universities (Thorley, 2017). Drawing on the experiences of student services staff, accounts of increasing demands on student services and the implications for the university can now be conceptualised as comprising four elements set within a broader environment and set of competing expectations [see Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Accounts of increasing demands on student services and the implications for the university.

4.1. Existing Demand

As set out in the introduction, student mental health is not a new concern for universities and there are ongoing, compelling reasons for universities to direct attention and resources towards providing appropriate support. Student services have a demonstrable track record in providing effective responses that can improve mental health, academic performance, academic persistence, and student experience. Even if whole university responses and societal improvements significantly reduce the current level of need, there always have been and always will be some students who require embedded, professional support within their university (Crook, 2020). As a result, universities have long provided services to meet this underlying need and this need will continue.

4.2. Reported Increase in Number of Student Service Requests

The participants in this research echoed the evidence in the literature (e.g., Thorley, 2017) describing an exponential growth in student demand. These numbers have outstripped the available resources in many UK universities, stretching the ability of student services to deliver safe, effective, and well-governed services (Mair, 2015; Randall & Bewick, 2016).

4.3. Rise in Complexity and Risk

Whilst some authors in the UK (Ecclestone, 2020; Ecclestone & Hayes, 2019; Ecclestone & Lewis, 2014; Arie, 2017) have attributed growing student demand for services to a pathologisation of everyday emotions, the complexity, severity, and risk present in this dataset do not support this trend. Consistent with previous findings (Akram et al., 2020), reported suicidal ideation was higher in this dataset [670 of 1400 referrals] than documented in the UK general population (Mulholland et al., 2021). Participants reported an increase in the number of students presenting with complex and challenging experiences and symptoms, alongside an increase in risk. This growth along all aspects of the mental health continuum suggests a more general rise in poor mental health across the population.

4.4. Limitations in Available NHS and Social Care Support

As a consequence of overstretched public health systems in the UK, universities are having to provide more support to students who are significantly ill and/or who present a risk to themselves.

These demands are contributing to a broader environment in which staff who are not mental health professionals are also having to respond to more and more severe disclosures from students. Indeed, it was found that where university support services cannot respond to student needs, students present elsewhere in the institution. Prior research (Hughes & Byrom, 2019) has likewise shown that demand is displaced within the institution rather than dissipated, which increases risk to the student, their peers, academic staff, staff in other areas such as halls of residence, and the institution itself (Payne, 2022; Hughes et al., 2018). Indeed, 55–65% of university staff are estimated to have been approached by a student to discuss their mental health (Farrer et al., 2015; Gulliver et al., 2018) yet 60% felt unequipped to respond (Gulliver et al., 2018). A total of 50–71% of UK academic staff have reported receiving little or no formal training, resources, or recognition and lack clarity around boundaries, responsibilities, and knowledge to safely and appropriately support students experiencing difficulties (Hughes et al., 2018; Hughes & Byrom, 2019; Margrove et al., 2014; McAllister et al., 2014). In particular, academic staff report difficulty distinguishing between pedagogical and personal or pastoral problems, concerns over perceived procedural delays in students’ accessing services, unfamiliarity with available services and their functions, and lack clarity or resources to implement reasonable adjustments for students within their role as educators (Payne, 2022; Ramluggun et al., 2022). Clarifying academic roles, responsibilities, and boundaries will be increasingly important in the context of the legal duty of care debate to support institutions to safely provide reasonable adjustments, enhance learning, and promote staff wellbeing as part of a whole university approach (Ramluggun et al., 2022; Spear et al., 2021).

Public, government, and media expectations of UK universities have also increased, placing more pressure on the role that student services can and should play. There is consequently a need for a clearer conceptualisation of the role of student services that is reflective of the current and ongoing reality (Barkham et al., 2019). While it is understandable that some universities may wish to hold a conception that sees mental health as being outside of their bailiwick, this is unsustainable in the contemporary post-COVID-19 environment and political context. If universities are to maintain student wellbeing, academic performance, persistence, and experience, they must continue to provide services that effectively meet the principles of good practice in the University Mental Health Charter (Hughes & Spanner, 2019). This requires services that are appropriately resourced, safe, effective, accessible, and well governed, with appropriate professional staff and a clear guiding purpose. Robust, professional services are better placed to build relationships with NHS and Social Care, and to more clearly define and maintain professional boundaries with academic staff.

Finally, it should not be lost, that despite the challenges faced by student services, the participants in this research continued to be proud of their work and the positive impact it has. Given the level of complexity and risk that is being supported by student services staff, it is not fanciful to suggest that there are students and former students today who are alive, successful, and flourishing because of the work of the professionals in university services. This is no small achievement.

5. Conclusions

This paper has presented student service staff experiences of responding to student mental health needs at UK universities. The findings help to specify the composition of demand for university support services as constituting an existing demand, an increase in overall presentation, an increase in the complexity and risk of presentation, and limitations in available NHS and Social Care provision. Significantly therefore, attributions of increasing service demand to a pathologisation of everyday emotions is not supported by the complexity, severity, and risk of symptomology reported in this dataset. The subsequent demand–resource gap described by participants can compromise the effectiveness, safety, and accessibility of university services and undermine the delivery of a whole university approach. Within this environment and amidst competing expectation, participants subsequently struggled to reconceptualise the role and responsibility of university services in relation to other institutional and external stakeholders. Taken together, the findings demonstrate the imperative for a clearer conceptualisation and investment in student services to ensure student success and safety, and to meet the principles of good practice in the University Mental Health Charter.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.H. and L.S.; methodology, G.H. and L.S.; formal analysis, G.H. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, G.H. and M.P.; writing—review and editing, G.H. and M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the UPP Foundation and The Office for Students, through the charity Student Minds, as part of the development of the University Mental Health Charter.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Derby Arts Humanities and Education Ethics Committee in January 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Access to the data is provided to experienced researchers who sign to accept the requirements of the ethical agreement and are part of the SMaRteN network.

Conflicts of Interest

Gareth Hughes supports Student Minds as a self-employed consultant and is the Content Development Lead for the University Mental Health Charter. Gareth is also a member of Student Minds Clinical Advisory Group. Michael Priestley works for Student Minds as a self- employed assessor for the University Mental Health Charter award scheme. Leigh Spanner was employed full time by Student Minds as Sector Improvement Lead and project manager for the University Mental Health Charter, at the time of gathering this data.

Appendix A. Focus Group Prompts

- What services do you provide for students who experience problems with their mental health while at university?

- What are the most common problems that students present with?

- What are the main challenges that university services face in delivering effective support?

- How cohesively do different services work together across the university? How well do student services work with academic departments?

- How do you measure the effectiveness of university services?

- What support do you provide for students with long-term mental health problems?

- Do you provide any specific interventions or services for groups you’ve identified as particularly vulnerable to developing mental health problems? Please give examples of these services, if any.

- What proportion of your students receive support from private providers versus in-house provision?

- How do you ensure that your teams or staff members are culturally competent and able to respond to the diversity of student need?

References

- Akram, U., Ypsilanti, A., Gardani, M., Irvine, K., Allen, S., Akram, A., Drabble, J., Bickle, E., Kaye, L., Lipinski, D., Matuszyk, E., Sarlak, H., Steedman, E., & Lazuras, L. (2020). Prevalence and psychiatric correlates of suicidal ideation in UK university students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 272(1), 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R., Kannangara, C., & Carson, J. (2023). Long-term mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students in the UK: A longitudinal analysis over 12 months. British Journal of Educational Studies, 71(6), 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arie, S. (2017). Simon Wessely: “Every time we have a mental health awareness week my spirits sink”. British Medical Journal, 358, j4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barden, N., & Caleb, R. (2019). Student mental health and wellbeing in higher education: A practical guide. SAGE Publications Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Barkham, M., Broglia, E., Dufour, G., Fudge, M., Knowles, L., Percy, A., Turner, A., & Charlotte, W. (2019). Towards and evidence-base for student wellbeing and mental health: Definitions, developmental transitions and datasets. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19(4), 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, R., Pitman, E., Sharpington, A., Stock, M., & Cage, E. (2020). Student perspectives on mental health support and services in the UK. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(4), 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J., Heron, J., Gunnell, D., Purdy, S., & Linton, M. J. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student mental health and wellbeing in UK university students: A multiyear cross-sectional analysis. Journal of Mental Health, 31(4), 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Medical Association. (2024). Mental health pressures in England. Available online: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/pressures/mental-health-pressures-data-analysis (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Broglia, E., Millings, A., & Barkham, M. (2017). Challenges to addressing student mental health in embedded counselling services: A survey of UK higher and further education institutions. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 46(4), 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broglia, E., Ryan, G., Williams, C., Fudge, M., Knowles, L., Turner, A., Dufour, G., Percy, A., Barkham, M., & on behalf of the SCORE Consortium. (2021). Profiling student mental health and counselling effectiveness: Lessons from four UK services using complete data and different outcome measures. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 51(2), 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. (2018). Student mental health: Some answers and more questions. Journal of Mental Health, 27(3), 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butlin, T., Lawton, B., Darougar, J., Jones, M., & Bradley, A. (2017). University and college counselling services. British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy. Sector Overview 003. Available online: https://www.bacp.co.uk/media/2237/bacp-university-college-counselling-services-sector-resource-003.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Cage, E., Stock, M., Sharpington, A., Pitman, E., & Batchelor, R. (2020). Barriers to accessing support for mental health issues at university. Studies in Higher Education, 45(8), 1637–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, S. (2020). Historicising the “crisis” in undergraduate mental health: British universities and student mental illness, 1944–1968. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 75(2), 193–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department for Education. (2024). How we’re supporting university students with their mental health. Available online: https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2024/03/14/how-supporting-university-students-mental-health/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Dooris, M., Cawood, J., Doherty, S., & Powell, S. (2010). Healthy universities: Concept, model and framework for applying the healthy settings approach within higher education in England. Available online: https://healthyuniversities.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/HU-Final_Report-FINAL_v21.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Duraku, Z., Davis, H., Arënliu, A., Uka, F., & Behluli, V. (2024). Overcoming mental health challenges in higher education: A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1466060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecclestone, K. (2020). Are universities encouraging students to believe hard study is bad for their mental health? Times Higher Education. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/are-universities-encouraging-students-believe-hard-study-bad-their-mental-health (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Ecclestone, K., & Hayes, D. (2019). The dangerous rise of therapeutic education (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecclestone, K., & Lewis, L. (2014). Interventions for resilience in educational settings: Challenging policy discourses of risk and vulnerability. Journal of Education Policy, 29(2), 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, L., Gulliver, A., Bennett, K., & Griffiths, K. M. (2015). Exploring the acceptability of online mental health interventions among university teaching staff: Implications for intervention dissemination and uptake. Internet Interventions, 2(1), 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, A., Farrer, L., Bennett, K., Ali, K., Hellsing, A., Katruss, N., & Griffiths, K. (2018). University staff experiences of students with mental health problems and their perceptions of staff training needs. Journal of Mental Health, 27(3), 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G. (2021). The challenge of student mental well-being: Reconnecting students services with the academic universe. In F. Padró, M. Kek, & H. Huijser (Eds.), Student support services. University development and administration. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G., & Byrom, N. (2019). Managing student mental health: The challenges faced by academics on professional healthcare courses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(7), 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, G., & Spanner, L. (2019). The university mental health charter. Student Minds. Available online: https://www.studentminds.org.uk/uploads/3/7/8/4/3784584/180129_student_mental_health__the_role_and_experience_of_academics__student_minds_pdf.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Hughes, G., Panjwani, M., Tulcidas, P., & Byrom, N. (2018). The role and experiences of academics. Available online: https://www.studentminds.org.uk/uploads/3/7/8/4/3784584/summary_of_the_report_the_role_and_experiences_of_academics_student_minds__1_.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Hughes, G., Upsher, R., Nobili, A., Kirkman, A., Wilson, C., Bowers-Brown, T., Foster, J., Bradley, S., & Byrom, N. (2022). Education for mental health: Enhancing student mental health through curriculum and pedagogy. Advance HE. Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/education-mental-health-toolkit (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Jacobs, M. (1979). Counselling within a student health service. In A. Wilkinson (Ed.), Student health practice. Pitman Medical Publishing Company Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, R., Knight, H., Ayling, K., Coupland, C., Corner, J., Denning, C., Ball, J., Bolton, K., Morling, J. R., Grazziela, F., Morris, D. E., Tighe, P., Villalon, A., Blake, H., & Vedhara, K. (2021). Prospective examination of mental health in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipe, D., Maughan, C., Gilbert, J., Dymock, D., Moran, P., & Gunnell, D. (2018). Mental health in medical, dentistry and veterinary students: Cross-sectional online survey. BJPsych Open, 4(6), 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, E., & Cardwell, J. (2018). A comparative study of mental health and wellbeing among UK students on professional degree programmes. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(9), 1226–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G., McCloud, T., & Callender, C. (2021). Higher education and mental health: Analyses of the LSYPE cohorts. Department for Education Research Report. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60d5d9af8fa8f50aad4ddac0/Higher_education_and_mental_health__analyses_of_the_LSYPE_cohorts.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Lewis, J., & Stiebahl, S. (2024). Student mental health in England: Statistics, policy, and guidance. House of Commons Library. Available online: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8593/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Macaskill, A. (2013). The mental health of university students in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 41(4), 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, C., & Cameron, J. (2021). Thriving learners: Initial findings from Scottish HEIs 2021. Mental Health Foundation Scotland. Available online: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/MHF-Thriving-Learners-Report-Full.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Mair, D. (2015). Short-term counselling in higher education: Context, theory, and practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margrove, K., Gustowska, M., & Grove, L. (2014). Provision of support for psychological distress by university staff, and receptiveness to mental health training. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38(1), 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, M., Wynaden, D., Happell, B., Flynn, T., Walters, V., Duggan, R., Bryne, L., Heslop, K., & Gaskin, C. (2014). Staff experiences of providing support to students who are managing mental health challenges: A qualitative study from two Australian universities. Advances in Mental Health, 12(3), 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, K., Murray, K., Murray, A., & Richelieu, M. (2015). The effectiveness of university counselling for students with academic issues. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 15(4), 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, S., & Gunnell, D. (2020). Trends in mental health, non-suicidal self-harm and suicide attempts in 16–24-year old students and non-students in England, 2000–2014. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(1), 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A. (2018). Psychological distress in student nurses undertaking an educational programme with professional registration as a nurse: Their perceived barriers and facilitators in seeking psychological support. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 25(4), 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, H., McIntyre, J., Haines-Delmont, A., Whittington, R., Comerford, T., & Corcoran, R. (2021). Investigation to identify individual socioeconomic and health determinants of suicidal ideation using responses to a cross-sectional, community-based public health survey. BMJ Open, 11(2), e035252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office for National Statistics [ONS]. (2020). Personal wellbeing, loneliness and mental health. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/educationandchildcare/articles/coronavirusandtheimpactonstudentsinhighereducationinenglandseptembertodecember2020/2020-12-21#personal-well-being-loneliness-and-mental-health (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Palinkas, L. A. (2014). Qualitative and mixed methods in mental health services and implementation research. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 43(6), 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, L., Tiffin, P. A., Barkham, M., Bewick, B., Broglia, E., Edwards, L., Knowles, L., McMillan, D., & Heron, P. (2023). Mental health trajectories in university students across the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from the student wellbeing at Northern England universities prospective cohort study. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1188690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, H. (2022). Teaching staff and student perceptions of staff support for student mental health: A university case study. Education Sciences, 12(4), 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M., Broglia, E., Hughes, G., & Spanner, L. (2021). Student perspectives on improving mental health support services at university. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(1), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, J. (2015). University student counselling and mental health in the United States: Trends and challenges. Mental Health & Prevention, 3(1), 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramluggun, P., Kozlowska, O., Mansbridge, S., Rioga, M., & Anjoyeb, M. (2022). Mental health in higher education: Faculty staff survey on supporting students with mental health needs. Health Education, 122(6), 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, E., & Bewick, B. (2016). Exploration of counsellors’ perceptions of the redesigned service pathways: A qualitative study of a UK university student counselling service. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 44(1), 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2021). Mental health of higher education students. Available online: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/mental-health-of-higher-education-students-(cr231).pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Rückert, H. -W. (2015). Students’ mental health and psychological counselling in Europe. Mental Health & Prevention, 3(1), 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, K., Priestley, M., Dodd, A. L., Broglia, E., Wykes, T., Robotham, D., Tyrrell, K., Ortega Vega, M., & Byrom, N. C. (2022). Key questions: Research priorities for student mental health. BJPsych Open, 8(3), e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, A., & Ferguson, K. (2014). The role of university support services on academic outcomes for students with mental illness. Education Research International, 1(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, S., Morey, Y., & van Steen, T. (2021). Academics’ perceptions & experiences of working with students with mental health problems: Insights from across the UK higher education sector. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(5), 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, N., Yalipende, Y., Byrom, N., Hatch, S., & Lempp, H. (2022). Mental health and mental wellbeing of black students at UK universities: A review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open, 12(2), e050720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streatfield, N. (2019). Professional support in higher education. In N. Barden, & R. Caleb (Eds.), Student mental health and wellbeing in higher education: A practical guide. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Student Minds. (n.d.). University communities come together to shape the university mental health charter. Available online: https://www.studentminds.org.uk/latestnews/university-communities-come-together-to-shape-the-university-mental-health-charter (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Thorley, C. (2017). Not by degrees: Improving student mental health in the UK’s universities. Institute for Public Policy Research [IPPR]. Available online: https://www.ippr.org/articles/not-by-degrees (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- UUK [Universities UK]. (2020). Stepchange: Mentally healthy universities. Universities UK. Available online: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Documents/2020/uuk-stepchange-mhu.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Walker, J. (1979). Student counselling services. In A. Wilkinson (Ed.), Student health practice. Pitman Medical Publishing Company Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, P. (2012). The impact of counselling on academic outcomes: The student perspective. University and College Counselling Journal, 6–11. Available online: https://www.bacp.co.uk/bacp-journals/university-and-college-counselling/november-2012/the-impact-of-counselling-on-academic-outcomes/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- World Health Organisation. (1986). The Ottawa charter for health promotion. WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/Ottawa/en/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Worsley, J., Pennington, A., & Corcoran, R. (2022). Supporting mental health and wellbeing of university and college students: A systematic review of review-level evidence of interventions. PLoS ONE, 17(7), e0266725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zile, A., Priestley, M., & Hughes, G. (2024). Learning from the university mental health charter: An analysis of outcomes reports. Student Minds. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).