In this section, we address each research question by presenting findings drawn from observational and interview data and providing discussions of the findings in light of the theoretical framework and literature review. In examining the epistemic and positional framing of students, we first report and discuss the epistemic goals of the SDCs as students understand them and the positions or roles that students believed they took up to work toward those goals. Then, we expand upon that understanding to describe the ways power was taken up or distributed within groups and how gender influenced the groups’ activity. Two primary takeaways emerged from this study: (i) the group shifted their epistemic and positional framings from collaborative problem solving in the first SDC to polarized positions of authority and a loss of authentic problem solving goals in the last SDC, and (ii) gendered power dynamics may have played a substantial role in this framing shift.

6.1. How Do Students Understand and Navigate Positional and Epistemic Framings While Participating in Argument-Driven Engineering Design Challenges?

Agency and argumentation are goal-oriented; epistemic agents know what they are trying to accomplish and what their roles are in terms of achieving those goals, including roles around sensemaking and shaping sensemaking practices within the group (

Stroupe et al., 2018). In engineering and design-based learning, the desired epistemic framing of goals involves designing solutions to problems. Additionally, engineering students may be expected to work collaboratively in groups, sharing responsibilities and equitably taking up positions of authority (

Patterson, 2019). In this study, the group initially positioned Kai in an epistemic agentive role and Benny and Bernadine positioned themselves in more technical roles as constructors and recorders, although Kai downplayed this positioning and the group was observed sharing or distributing epistemic agency. These students emphasized that they organically took up these roles based on their abilities and the group’s needs. Later, during the final SDC, Jeremy was positioned as an authority, while Kai struggled to maintain her role as an authority and collaborator. The epistemic framing shifted during the final SDC as well, with Kai and Bernadine in particular losing sight of the goal of the SDCs; they no longer sought to design the best solution for their ‘client,’ but instead sought to finish their design “so we don’t have to go through this again” (from Stage 6 transcript). Their roles became less epistemically focused on finding an effective solution and more procedural, focusing on completing a school task.

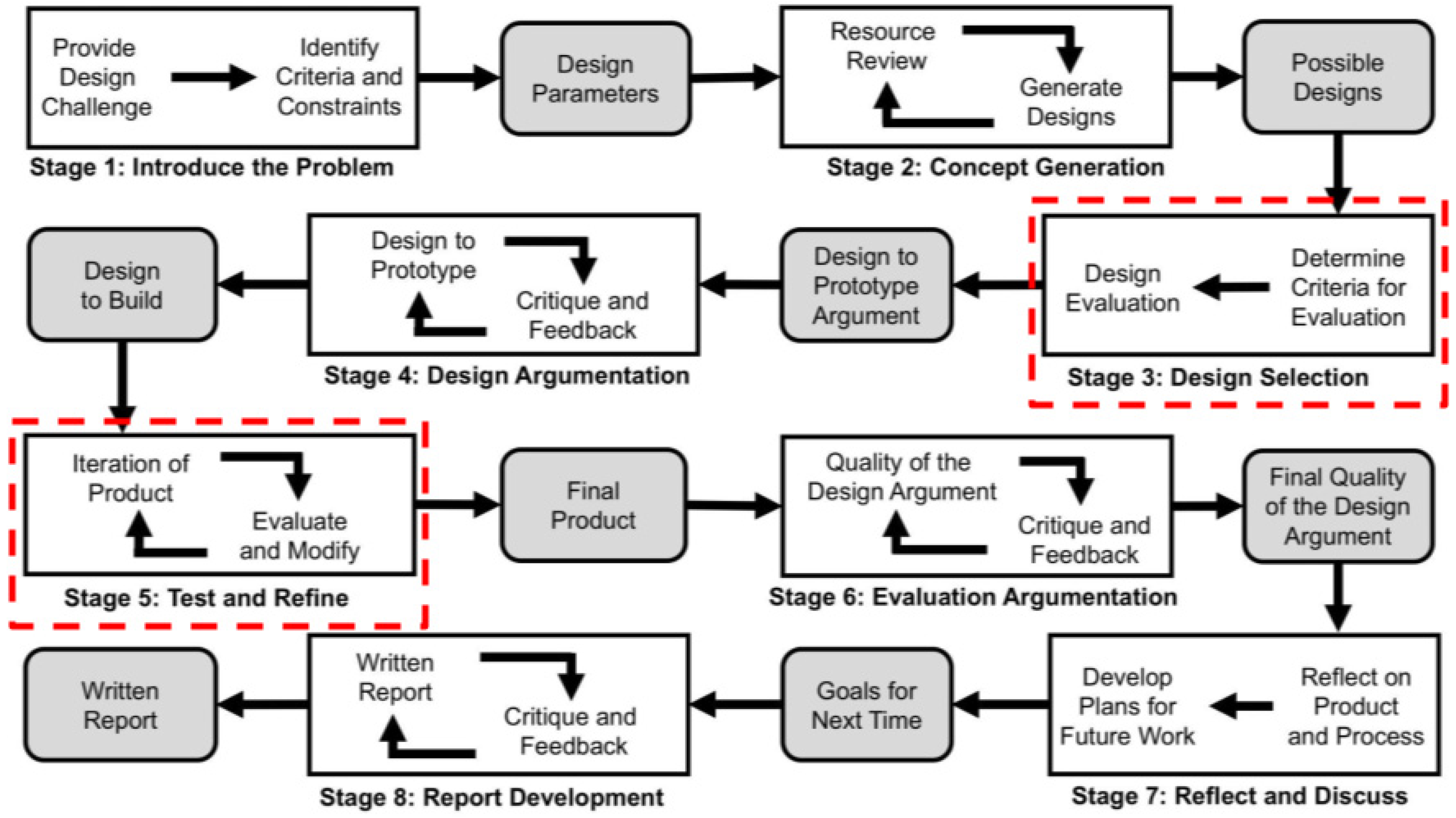

The group identified problem solving as the epistemic goal of the SDCs and framed knowledge construction as a general epistemic goal in Mr. Martin’s class. As Lacey described during the focus group interview, “You’re given a list of constraints and criteria, and … you’re trying to design something that a ‘client’ has requested”. In this case, Mr. Martin acted as the hypothetical client who was requesting design prototypes for a particular need (i.e., storing and insulating vaccines without electricity and reducing injury from vehicle collisions). These students generally felt that the teacher emphasized learning as a goal in his class, saying that Mr. Martin “just tries his hardest to make sure that we learn what he’s trying to teach us” (Lacey) and “He wants us to pass [the state standardized test] so he makes sure that we know everything” (Bernadine). Students described the goal of their groupwork, or epistemic framing, in terms of knowledge-building and designing solutions, suggesting that they understood their roles to be important for sensemaking (

Berland & Reiser, 2011;

Cunningham & Kelly, 2017;

Odden & Russ, 2019) and that they acted in these roles as epistemic agents, meaning that they shaped the epistemic practices of their group (

Stroupe et al., 2018).

When the group was asked to describe their specific roles, they spoke to a division of labor they naturally “fell into”. This mostly reflects the positional framing of their activity in technical roles. Sometimes, this was based on a student’s strengths or weaknesses. As Lacey noted, “I did not trust myself with the hot glue because the first project we did, I severely burned myself … [so] I made quite a few designs and helped with the building that did not involve glue. I usually got the supplies and stuff”. Benny and Bernadine both worked on the actual building of the prototypes, with Bernadine noting, “I just kind of did most of the hot glue because I like hot glue”. Benny additionally worked in the packet, which was given to students to provide information such as client needs and structure for planning and recording tests and arguments. Kai was less certain of her role: “I just remember panicking a lot. I didn’t know what to do because it was like, we’re already over budget”. However, Lacey explicitly positioned Kai as the leader, and Bernadine attributed science knowledge authority to Kai:

Interviewer: Lacey called you a leader?

Lacey: Yeah, you were kind of more of the-

Kai: I just-

Bernadine: You were really good at the science part of it.

Lacey: You’re more organized, I think, even though you were panicking.

Kai: I just did what needed to be done in the packet.

From these self-reflections of roles and positions, Lacey and Bernadine thought that Kai held a position of some power or authority, leading and organizing the group, but Kai thought of her own actions as less influential and based more on the group’s needs, just “doing what needed to be done”. Kai seemed to undervalue her position, despite having a hand in most if not all aspects of the design process. This is explored more in the next section. From the observations of student discourse, Kai did take on a position of authority and agency, developing many solutions and advocating for her ideas. For example, Kai shared her two vaccine storage design concepts early in Stage 3 of the first SDC:

| Turn | Talk |

| 3 | Kai: So, who’s going first? |

| 4 | Lacey: I volunteer you as tribute. |

| 5 | Kai: Dang it. Yeah, that’s cool. Okay. I’m a messy writer so it looks like a lump of dust. But, I wanted to get the box and we’d buy two boxes so we could use one as insulation because everything else is expensive. We’d buy one freezer bag, put it at the bottom. We’d take a bunch of batting and put a couple layers and then, yeah, basically… |

| 6 | Lacey: Can I see? |

| 7 | Kai: It would be a box, we’d put another box in the box with a bunch of batting on the outside. |

| 8 | Benny: What are the names of them? |

| 9 | Kai: I just put Concept 1 and Concept 2. The cost is exactly $15. |

| 10 | Lacey: And what’s the second one? |

| 11 | Kai: Here, let me see. Basically instead of building two boxes, we buy one box. We cut it up, make a mini box, and then we put three layers of the cardboard and three layers of the batting and then we put- |

| 12 | Lacey: Is the batting on the inside or the outside? |

| 13 | Kai: The inside. |

| 14 | Lacey: Okay. |

| 15 | Kai: And then we cover that portion of the three and then three layers of batting another piece of cardboard with a freezer bag at the bottom and the vaccine on the inside with kind of like a insulatable, but like clip it so that it won’t break. Keep it in place. It would be two splits on the side and make a club or handle. |

| 16 | Lacey: Nice. |

| 17 | Kai: And get a sill seal and then put it on the edge so that the heat doesn’t leak out. |

In this example, we see Kai and Lacey negotiating the first sharer. As Kai shared her design concept, we also see how she connected the materials to the goals of being able to transport the vaccine using a club or handle and to reduce heat transfer (into the box, though she misspoke). Kai also kept the group on task, adding credence to Lacey’s description of Kai as a leader. This type of collaborative exchange was typical during the first SDC, as Lacey reflected on in the interview: “I feel like a lot of our ideas were super similar … kind of an amalgamation of all of us”. Previous studies show the importance of collaboration in argumentation as students negotiate epistemic authority and agency (

Chen, 2020;

Engle et al., 2014;

González-Howard & McNeill, 2020;

Ha & Kim, 2021). Negotiations of epistemic authority, or who is positioned as a capable knowledge producer (

Engle et al., 2014), were seen when Lacey described herself as making “quite a few designs” in the interview and the group positioned Kai as a “leader” and epistemic authority for science knowledge during the first SDC.

However, there was a marked change during the final SDC, when Jeremy joined the group, replacing Lacey. Although Jeremy was not interviewed and as such could not speak for himself, the original group noted that he disrupted their positioning around shared or flexible roles. As Bernadine reflected, “I feel like he did most of the work, like he pushed us away and did most of the work”. The other group members described the way Jeremy took over the group and pushed forward his design concept without discussion and did not contribute to the work of completing the packet. During the focus group interview, Bernadine and Benny shared the following about Jeremy’s decision to use his design concept despite there being disagreement on the groups’ ranking matrices, where the lowest score represents the best design concept across multiple criteria:

Bernadine: [Jeremy’s concept] was the highest [score] on mine [ranking matrix] and it was the lowest on his … and he was like, ‘Okay we’re doing my idea!’ Because-

Benny: Yeah, without any say. …

Bernadine: He was like, ‘Oh we’re doing my idea,’ and then he was talking, and talking, and talking, and he wouldn’t write anything down and I was writing stuff down and I was trying to give him my ideas and he wouldn’t listen. And then when he wrote nothing down, he was trying to copy off my work.

While the group had previously worked collaboratively, sharing ideas and each contributing to the design process, most of the dialog and idea generation observed during the final SDC was dominated by Jeremy and Kai, which polarized the group and hindered their design work. At the same time, Jeremy refused to write in his packet as the discussion moved forward, instead relying on Bernadine to record his ideas and copying from her work later, positioning her in a technician role.

In another example, we see Jeremy and Kai competing to share their design concepts with the rest of the group. On the second day of Stage 3, Mr. Martin began class by reminding students about the criteria and constraints of the design challenge and how to use the criteria and constraints to rank and select a concept. Kai returned to describing her design concept, but Jeremy and Benny held a simultaneous conversation about Jeremy’s design concept:

| Turn | Talk |

| 101 | Kai: Can we just get two popsicle sticks? |

| 102 | Bernadine: Kai, thank you for explaining yours, ‘cause I didn’t- [crosstalk] |

| 103 | Kai: Just take popsicles and glue them on the side. Call it a day. |

| 104 | Bernadine: I was thinking of putting like… Mine wouldn’t work, so I was thinking instead of just doing popsicle sticks, putting foam, too. [crosstalk] |

| 105 | Jeremy: Okay. Mine is $6.75. |

| 106 | Kai: Oh, I haven’t finished- |

| 107 | Bernadine: Yeah, Kai hasn’t finished. |

| 108 | Kai: -from like yesterday. Okay. So. it’s like- |

| 109 | Jeremy: Actually, $6.25 would have to [crosstalk]- |

| 110 | Kai: -the same design for both of them. |

| 111 | Jeremy: -because [inaudible] |

| 112 | Kai: Basically, you either use a jug or popsicle sticks. Because, like- I just made a thing of rice, sand, and foam in the middle, so it’d compress. |

| 113 | Jeremy: $6.25. |

In this example, Jeremy took up a position as an epistemic authority but did not allow others to share in this role. Kai attempted to continue maintaining her own epistemic authority to share her concept, but this episode was not productive with both students talking over one another. Neither allowed the other to take up the position of sharer in this moment. Similar polarized dynamics were observed by

Shim and Kim (

2018) and

González-Howard and McNeill (

2020), although neither of these studies explicitly examined gender as a factor; the influence of gendered power dynamics will be discussed in the next section.

Along with this disruption of positional framing, we also observed a substantial shift in the nature of the epistemic framing of the task in the final SDC compared to the first. For example, near the end of Stage 3, Kai suggested that they combine her concept with Jeremy’s concept before building it, similar to what the group had done during the first SDC.

| Turn | Talk |

| 521 | Kai: Before we start, we might want to consider refining the design. I wasn’t completely sure about how technical the- |

| 522 | Jeremy: Well, the thing is we’re supposed to refine the design after our- |

| 523 | Kai: Yes, but before we build it, we should probably make sure that it’s the best. |

| 524 | Bernadine: But if we make it work the first time, then we won’t have to do it again. |

| 525 | Kai: We’d have to do better than- [crosstalk] |

| 526 | Jeremy: Well, the thing is we still need to find out all the problems and then just- |

| 527 | Kai: Can we just- |

| 528 | Jeremy: Who knows, Styrofoam might cause a problem itself. You don’t know that. |

| 529 | Kai: What Styrofoam? There’s nothing in the cost… |

| 530 | Jeremy: Well, you said something about using the Styrofoam cup instead of a plastic bottle. |

| 531 | Kai: What? No, I wasn’t saying that. Just say put it to the design because all we have is a bottle. So- |

| 532 | Jeremy: We’ll add the stuff after to refine the design. |

| 533 | Kai: But then we won’t have to if we do it right the first time. |

| 534 | Jeremy: Well, the thing is, that we already agreed upon this idea. I don’t think we should refine it, and we should find all the problems- |

| 535 | Kai: I’m just concerned that it’s not going to work. |

Kai’s suggestion was critiqued by Jeremy, who advocated for using his design as it was, and adding that “we’ll add the stuff after [we test it] to refine the design,” representing a more methodological approach. This disagreement about altering the design occupied much of the discussion throughout this SDC and reflects a significant difference in the epistemic framing between Jeremy’s strict methodological approach and the rest of the groups’ creative, generative approach that allowed for adjustments to and combinations of design concepts prior to building. Mr. Martin supported Jeremy’s framing, most clearly observed when he told the group “What you’ll do is decide which one you’re building. Build it then I’ll let you make modifications to it. The first one you design, you test it. The way it is, no modifications” (turn 411). Notably, the ADE framework is intended to encourage peer feedback and critique followed by adjustments to design concepts in Stage 4; this stage was skipped by Mr. Martin in the final SDC due to time constraints.

The group never did revise Jeremy’s initial idea, even after building and testing. Conflict within the group resulted in first Kai and then Bernadine disengaging from the design goals. When discussing the size of a highway crash barrier design concept, Kai states that “To be completely honest, let’s just build it, I don’t—As long as it’s not overly giant…” (turn 221). As the group attempted to decide on a concept to move forward with, they realized that they had a tie between several design concepts across all criteria. The group appealed to Jeremy to rank the concepts again, without focusing on accuracy:

| Turn | Talk |

| 271 | Kai: Just rank it Jeremy. |

| 272 | Bernadine: Just rank it. |

| 273 | Kai: One through four. |

| 274 | Bernadine: Doesn’t have to be scientifically perfect. |

| 275 | Benny: Just assume. |

| 276 | Kai: Just rank it. It’s not going to be accurate either way. |

| 277 | Jeremy: Okay. I agree mine would be two. |

| 278 | Kai: We don’t have all the measurements. Mr. Martin? |

| 279 | Mr. Martin: Did you pick somebody [to collect data on their Chromebook]? Are they logged on? |

| 280 | Benny: Don’t do same numbers. |

| 281 | Kai: Is this the last one of these we’re going to do this year? Okay. Thanks. |

| 282 | Jeremy: So whoever I give number one would be the one we use, obviously. |

| 283-285 | [off-topic talk] |

| 286 | Jeremy: Just to be sure I’m accurate. This one based on… |

| 287 | Kai: Jeremy, which one do you think will work? |

| 288 | Bernadine: Yeah, it’s not that hard. You don’t have to determine each one. You don’t have to go, hm-mm-hmm [affirmative]. Hm-mm-hmm [affirmative]. Hm-mm-hmm [affirmative]. Just go- |

| 289 | Kai: Which one do you think will work? |

| 290 | Bernadine: Done. |

| 291 | Kai: And rank. |

Here, we see Kai, Bernadine, and Benny encouraging Jeremy to just rank the concepts based not on “scientifically perfect” or “accurate” criteria (turns 274-276), but based on which he assumes “will work” (turn 287). When Jeremy declares his own concept “Sand Bottle” to be the decision, Kai clarifies, “Okay, so we can do Sand Bottle?” (turn 312) to which Bernadine responds, “I don’t care” (turn 313). This reflects a shift in the epistemic framing of the purpose of the SDC as well as a shift in authority to Jeremy to make decisions, regardless of performance metrics or collaboration between group members.

With the change in group composition, we observed how polarized power dynamics, specifically masculine hegemony (

Due, 2014), interfered with the uptake of epistemic agency by reducing equitable participation in the group during the last SDC and changing the epistemic framing of the purpose of the SDC. Notably, Benny, the consistent boy in the group throughout the SDCs, did not leverage masculine hegemony or power over the rest of the group. He typically played a muted role, approving of or adding to others’ ideas without competition or polarization and contributing to the building of the prototype in later stages. Benny offers an example of what

Due (

2014) refers to as a “supporting and conflict-avoiding boy” (p. 450).

6.2. How Do Interactions Between Group Members and Their Reflections Reveal Gendered Power Dynamics?

Gender influences the ways in which students interact with one another (

Due, 2014) and how students position themselves through empowered or disempowered positions (

Carr, 2003). In this study, we observed dramatic, negative shifts in how the group resolved problems or disagreements and the ways that the girls in the group talked about their own knowledge and abilities over time. This is likely the result of the group composition changing, which disrupted the interactions and dynamics the group had established through previous SDCs. Jeremy’s presence in the group, and his different ideas about how the task should be completed, caused conflict within the group. Simultaneously, Kai and Bernadine changed how they talk about their own capabilities, disparaging themselves rather than building one another up. Specifically, we observed differences in the ways that the group resolved problems or disagreements and the ways that the girls in the group talked about their own knowledge and abilities.

During the first SDC, when Lacey noticed a problem with Benny’s design concept called “Batman,” the group worked together to brainstorm a solution:

| Turn | Talk |

| 81 | Lacey: Okay so what’s the Batman? |

| 82 | Benny: Cardboard box but cut it down to as big as the 8 oz. water bottle and then put a freezer bag inside the water bottle and then sill seal at the top. |

| 83 | Lacey: So is that a box or a bag? Sorry. |

| 84 | Benny: Box. |

| 85 | Lacey: Okay. |

| 86 | Benny: Insulation on the top also. |

| 87 | Kai: Can I see? |

| 88 | Lacey: How much is it? |

| 89 | Benny: $13.75. |

| 90 | Lacey: $13.75. Well here’s the thing, I saw how big the ice pack was and it might not fit in the water bottle. |

| 91 | Kai: We could maybe just wrap it on the outside. |

| 92 | Benny: You could put it like- [mimes wrapping an ice pack around a water bottle] |

| 93 | Lacey: And then put the vaccine in the water bottle? |

| 94 | Benny: Yeah. |

| 95 | Kai: I think that’s a good idea. I like this one. |

Lacey realized in turn 90 that the ice packs available to them would not fit inside a plastic water bottle, as Benny had originally planned (turn 82). Kai’s suggestion in turn 91 was accepted by Benny and Lacey. Additionally, in this event, we see Kai praising Benny’s concept as a “good idea”.

This contrasts with an event seen during the last SDC. Jeremy’s highway crash barrier design concept involved a plastic water bottle filled with sand. Kai had noted earlier that the compression test result data they had access to showed that Styrofoam “tested really well” with a compression ratio of 3.59 (compression distance to mass). She was concerned that the plastic water bottle would compress too much without absorbing enough force.

| Turn | Talk |

| 444 | Kai: We need to compress… |

| 445 | Jeremy: We can cut a different portion of the bottle if we need to. |

| 446 | Kai: Yes, but like, my problem is plastic is really easy to compress. It’s not going to take that much impact. |

| 447 | Jeremy: I see where you’re coming from. But it’s also fairly cheap for what we’re doing. |

| 448 | Kai: It is cheap but will it work? ‘Cause Styrofoam- |

| 449 | Bernadine: Yours cost like $6, we still, like… it doesn’t- |

| 450 | Kai: Styrofoam is also cheap and it compresses more. |

| 451 | Bernadine: Yeah. Styrofoam would work better. We probably wouldn’t have to build it again if it worked the first time. |

| 452 | Jeremy: So let’s try the plastic the first time and then we’ll try the Styrofoam to see if that does better. |

| 453 | Kai: I was- So… it’s just the bottle and then sand. |

| 454 | Jeremy: Bottle, sand, popsicle sticks and then foam on the bottom. |

In this instance, when Kai brought up a potential issue with the materials in Jeremy’s design concept, Jeremy first defended the plastic as cheap (turn 447), which Kai and Bernadine disputed in turns 448–451, with Styrofoam also being cheap and more effective. Then, Jeremy appealed to a methodical approach, citing that they can change the material after testing (turn 452). The group continued to unproductively dispute various aspects of Jeremy’s Sand Bottle concept for the remainder of the class period and into the next day they worked on the SDC. As described in the previous section, Kai and Bernadine gave up their efforts and eventually disengaged from the design process.

We also observed a change in the ways the girls’ talked about themselves and one another. During the first SDC, there were several instances of empowering talk and praise. For example, in turn 95, Kai praises Benny’s Batman concept, saying “I think that’s a good idea. I like this one”. Soon after, Bernadine describes her design concept; Kai similarly tells her “That’s genius. How big is it? Did you cut up the box just regular?” (turn 98). Likewise, Bernadine agrees with the groups’ shared idea to insert the vaccine Falcon tube into the water bottle in place of the screw-on cap, saying “That’s smart. That’s smart” (turn 177). These are examples of praising and empowering language (

Carr, 2003) used during the first SDC, as Kai and Bernadine complimented one anothers’ design concepts and ideas as “smart” and “genius”. Importantly, a distribution of power was performed in part through this intentional encouragement by peers to share their ideas and thoughts, similar to what

Bennett et al. (

2010) and

Ha and Kim (

2021) found.

However, this changed during the final SDC. Rather than empowering each other and complimenting one another’s ideas, Kai and Bernadine shifted to using disempowered language (

Carr, 2003), especially when referring to themselves. For example, when calculating the weight of her highway crash barrier concept, Kai struggled, commenting “I got, um… I can’t do math” (turn 121). Bernadine responded, “Yesterday I didn’t know two plus two” (turn 121). Later, still trying to estimate the total weight of her design concept, Kai again disparages her own abilities:

| Turn | Talk |

| 155 | Bernadine: How many grams of rice- |

| 156 | Kai: I’d say, like 15. |

| 157 | Bernadine: 15 g? |

| 158 | Kai: I don’t know. I can’t make this. |

| 159 | Jeremy: Did you use any sand or rice? |

| 160 | Kai: I used rice. |

| 161 | Jeremy: Okay, that’s 100 g. |

| 162 | Kai: Then like, 150. |

| 163 | Jeremy: 150. |

| 164 | Kai: I’m not good at weight. |

| 165 | Jeremy: Let me see. [Kai hands her packet to Jeremy] Let’s see here. Okay, so, popsicle sticks. That’s… |

| 166 | Kai: Don’t pay attention to the thing at the bottom. |

| 167 | Jeremy: M’kay. If I had to estimate, 150 g. |

| 168 | Kai: Okay. |

Bernadine and Jeremy prompt Kai to calculating a reasonable weight estimate for her concept, but Kai continues to second-guess herself, saying she cannot do it (turn 158) or that she is not good at it (turn 164). When Jeremy comes to the same weight estimate (turn 167) that she herself stated earlier (turn 162), Kai simply accepts his answer, saying “Okay” (turn 168).

Later, we again see Kai and Bernadine referencing disempowering language, as they estimate the size of their design concepts and became confused about area and volume:

| Turn | Talk |

| 204 | Kai: Not perfectly to scale but I just… That is I believe eight centimeters, nine centimeters, in length. … So I’m just going to say it’s about nine. With all the foam and the thing on the tip, that’s three for the width. Hold on, let me- |

| 205 | Jeremy: Nine for width, what’s the height? |

| 206 | Kai: Okay, like 162 cm cubed. |

| 207 | Bernadine: It’s squared not cubed. |

| 208 | Kai: I thought it was supposed to be cubed. |

| 209 | Bernadine: No. It’s squared. |

| 210 | Kai: But his thing [the teacher’s instructions on the whiteboard] says cubed. |

| 211 | Bernadine: I think you said cubed. That confused him, hold on. [looking through packet] |

| 212 | Jeremy: Cubed is- |

| 213 | Bernadine: I don’t know what cubed means. |

| 214 | Jeremy: -width, length, and height. |

| 215 | Bernadine: Am I supposed to know what cubed means? Because I don’t know. |

| 216 | Kai: It’s supposed to be cubed right? So I multiplied width, length, and height. |

| 217 | Bernadine: I just put 129 cm squared. |

| 218 | Kai: Then why’d he write cubed? Okay, it’s like, 52 cm squared. |

| 219 | Jeremy: So yours is around 52 cm squared? |

| 220 | Bernadine: I have no idea what mine is. |

Kai thought that the “size” measurement they should use was the three-dimensional cubic size of the entire highway crash barrier, rather than the footprint area where the barrier would fit onto the test track. Despite “cubed” being written on the whiteboard, she accepts Jeremy and Bernadine’s claim that the correct size metric should be squared. Further, in turns 213 and 215, Bernadine claims she does not know what cubed means. In contrast, the only empowering language observed in Stage 3 of the final SDC came from Jeremy, when he was referring to his SDC 1 vaccine storage design in his previous group. He stated “I mean, my table was literally just trying to change all of my design when they came down to my design, for every- and I was pretty good in most stats” (turn 334).

These disempowered comments from Kai and Bernadine reflect a broader pattern throughout the final SDC, which sharply contrasts to the first SDC, where these girls often referred to their own abilities using empowering language. Some context for this shift may be seen in the interview, where Bernadine reflected that she does not always speak up out of fear of being described as bossy: “when I was little I used to be really bossy so I try not to be as bossy so I don’t talk as much”. Her disempowered talk about her own intelligence may be her way of stepping back from any authoritative positioning. Similarly, Kai minimized her role in the SDCs, saying that she “just did what needed to be done in the packet”. This is very different from the leadership role she was observed to take up in the group.

Only in the final SDC, after the group composition changed, did we see instances of disempowered language (

Carr, 2003) and a pattern of epistemic oppression (

Dotson, 2014;

Fricker, 1999;

Pohlhaus, 2020); this served to diminish the contributions and positioning of the girls in the group (Kai and Bernadine). Additionally, Bernadine’s avoidance of taking up space to talk in order to avoid being perceived as “bossy” is emblematic of how girls uniquely experience the label of “bossy” as a microaggression (

Clerkin et al., 2015). In understanding engineering to be a male-dominated field (e.g.,

Kinzie, 2007;

Malicky, 2003;

Morelock, 2017) wherein girls view themselves and are viewed by their peers as less competent or capable (e.g.,

Due, 2014;

Master et al., 2017;

Nazar et al., 2019), we attribute the polarized structure of Mr. Martin’s group during the final SDC and the positioning of Jeremy as empowered and his group—including his exclusion of his peers’ ideas as well as Bernadine’s hesitancy to seem “bossy”—as a function of masculine hegemony (

Due, 2014). Jeremy’s competitive pushing for his ideas caused the whole group to lose meaning in their activity (

Berland et al., 2016), and their epistemic agency subsequently suffered. Without group cohesion, these students changed their goal for the task from one of epistemic importance—designing a solution to a real-world problem—to one of “doing the lesson” (

Jiménez-Aleixandre et al., 2000).