Effectiveness of a Training Program on the Psychological Well-Being and Self-Efficacy of Active Teachers, Controlling for Gender and Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Well-Being in Teachers

1.2. Teacher Self-Efficacy

1.3. Impact of Gender and Teaching Experience

1.4. Training Programs: A Key Strategy for Teacher Well-Being and Self-Efficacy

1.5. The Present Study

1.6. Objectives and Hypotheses

- Objective 1: to analyze whether there is a significant increase in all factors of psychological well-being in the experimental group of teachers compared to the control group after the training.

- Objective 2: to analyze whether there is a significant increase in all factors of teacher self-efficacy in the experimental group of teachers compared to the control group after the training.

- Objective 3: to examine the effectiveness of the training program in improving psychological well-being and teacher self-efficacy once the effect of the covariates of gender and years of teaching experience has been controlled for.

- Hypotheses 1: the implemented training program is effective in significantly improving the psychological well-being and teacher self-efficacy of the experimental group compared to the control group.

- Hypothesis 2: the implemented training program is effective in significantly improving the psychological well-being and teacher self-efficacy of the experimental group compared to the control group, once the effect of the covariates of gender and years of teaching experience has been controlled for.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Psychological Well-Being

2.2.2. Teacher Self-Efficacy

2.2.3. Training Program EmpowerTeach: Building Well-Being and Self-Efficacy

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Design and Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Training Program Overview

| Module | Objectives | Content | Methodology |

| Psychological well-being |

|

|

|

| Teaching effectiveness |

|

|

|

| Professional development |

|

|

|

References

- Acosta-Faneite, S. F. (2023). Competencias emocionales de los docentes y su relación con la educación emocional de los estudiantes. Revista Dialogus, 1(12), 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M. (2019). Psychological wellbeing of University Teachers in Pakistan. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 6(2), 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Pincay, R. C., Mendoza-Vega, A. J., Reasco-España, V. N., Morán-Ortiz, M. E., & Vera-Arias, M. J. (2024). El desarrollo profesional y la colaboración docente. revisión literaria. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 7(6), 8870–8881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansley, B. M., Houchins, D. E., Varjas, K., Roach, A., Patterson, D., & Hendrick, R. (2021). The impact of an online stress intervention on burnout and teacher efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 98, 103251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Muñoz, A. M. (2019). Perfil docente, bienestar y competencias emocionales para la mejora, calidad e innovación de la escuela. Pedagogía, Filosofía y Educación Prenatal, 8(5), 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy the exercise of control. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, A. (2023). Impact of psychological wellbeing on job performance of employees. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto-Rivas, M. E., Molina-Naranjo, M. J., & Mendoza-Bravo, K. L. (2021). Educación emocional: Factor clave en el proceso educativo. Revista Cognosis: Revista de Filosofía, Letras y Ciencias de la Educación, 6, 19–28. Available online: https://dialnet.uniroja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8538859 (accessed on 9 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Sánchez, J. A. (2023). Modelo explicativo del bienestar subjetivo en función de la autoeficacia, bienestar psicológico y optimismo de profesores de una universidad privada [Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León]. [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal-Aréstegui, F. I. (2023). Influencia del estrés laboral en el bienestar psicológico de profesores en Ayacucho. Revista Educación, 21(22), 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquerra, R., Pérez, J. C., & García, E. (2015). Inteligencia emocional en educación. Editorial Síntesis. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, A., & Díaz, D. (2005). El bienestar social: Su concepto y medición. Psicothema, 17(4), 582–589. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/727/72717407.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Buitrago-Orjuela, L. A., Barrera-Verdugo, M. A., Plazas-Serrano, L. Y., & Chaparro-Penagos, C. (2021). Estrés laboral: Una revisión de las principales causas consecuencias y estrategias de prevención. Revista Investigación en Salud Universidad de Boyacá, 8(2), 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I., & Kim, L. E. (2020). Teacher self-efficacy, instructional quality, and student motivational beliefs: An analysis using multilevel structural equation modeling. Learning and Instruction, 66, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caichug-Rivera, D. M., Ruíz, D. L., & Laurella, S. L. (2021). El estrés laboral, COVID-19 y otros factores que determinan el bienestar docente. I2D Revista Científica, 1(1), 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Palacio, I. C. (2023). Educar para el bienestar: Una condición para la formación de maestros en servicio. Voces y Silencios: Revista Latinoamericana de Educación, 14(1), 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, E. M. M., Gonzalez, A. F., & Jacott, L. (2018). Teachers’ subjective well-being and satisfaction with life. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 16(1), 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Gualda, R., Herrero, M., Rodríguez-Carvajal, R., Brackett, M. A., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2019). The role of emotional regulation ability, personality, and burnout among Spanish teachers. International Journal of Stress Management, 26(2), 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D. (2008). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy among Chinese secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 28(2), 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien-Duong, A., Nhung-Nguyen, H., Tran, A., & Minh-Trinh, T. (2023). An investigation into teachers’ occupational well-being and education leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1112577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Herrada, M. I., & García-Horta, J. B. (2024). La salud mental y su relación con el bienestar psicosocial en profesores. Políticas Sociales Sectoriales, 2(2), 431–448. Available online: https://politicassociales.uanl.mx/index.php/pss/article/view/102 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Del Valle, S., De la Vega, R., & Rodríguez, M. (2015). Percepción de las competencias profesionales del docente de educación física en primaria y secundaria. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte, 15(59), 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dhanabhakyam, M., & Sarath, M. (2023). Psychological wellbeing: Asystematic literature review. International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology, 3(1), 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, A., Ilaltdinova, E., & Frolova, S. (2020). Teachers’ professional well-being: State and factors. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(5), 1698–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiman-Nemser, S. (2003). What new teachers need to learn. Educational Leadership, 60(8), 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, W., Wang, L., He, X., Chen, H., & He, J. (2022). Subjective well-being of special education teachers in China: The relation of social support and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 802811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Delgado, Y., García-Álvarez, E., López-Aguilar, D., & Álvarez-Pérez, P. R. (2023). Incidencia del género en el estrés laboral y burnout del profesorado universitario. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 21(3), 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C. (2010). La identidad docente: Constantes y desafíos. Revista Interamericana de Investigación. Educación y Pedagogía, 3(1), 15–42. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=561058717001 (accessed on 10 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gilar-Corbi, R., Pozo-Rico, T., & Castejón-Costa, J.-L. (2018a). Desarrollando la inteligencia emocional en educación superior: Evaluación de la efectividad de un programa en tres países. Educación XX1, 22(1), 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilar-Corbi, R., Pozo-Rico, T., Pertegal-Felices, M. L., & Sanchez, B. (2018b). Emotional intelligence training intervention among trainee teachers: A quasi-experimental study. Psicologia, Reflexao e Critica, 31(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, P. (2008). Creencias epistemológicas y de eficacia docente de profesores que postulan al programa de acreditación de excelencia pedagógica y su relación con las prácticas de aula [Ph.D. dissertation, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile]. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Pozo, C., Schoeps, K., Montoya-Castilla, I., & Gil-Gómez, J. A. (2024). Impacto de la inteligencia emocional y del clima escolar sobre el bienestar subjetivo y los síntomas emocionales en la adolescencia. Estudios sobre Educación, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Blanck, W. C. (1999). Análisis multivariante. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Jácquez, L. F., & Ceniceros-Cázares, D. I. (2018). Autoeficacia docente y desempeño docente, ¿una relación entre variables? Innovación Educativa, 18(78), 171–192. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-26732018000300171 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Huertes del Arco, A., Elvira-Valdés, M. A., Izquierdo-Sotorrío, E., & Roa-González, J. (2023). Estado de ánimo de los docentes en el contexto educativo español. In M. Molero-Jurado, A. Martos-Martínez, P. Molina-Moreno, M. Pérez-Fuentes, & S. Fernández-Gea (Eds.), Nuevas perspectivas de investigación en el ámbito escolar: Abordaje integral de variables psicológicas y educativas (pp. 55–562). Dykinson. [Google Scholar]

- Kuk, A., Guszkowska, M., & Gala-Kwiatkowska, A. (2021). Changes in emotional intelligence of university students participating in psychological workshops and their predictors. Current Psychology, 40, 1864–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarides, R., Fauth, B., Gaspard, H., & Göllner, R. (2021). Teacher self-efficacy and enthusiasm: Relations to changes in student-perceived teaching quality at the beginning of secondary education. Learning and Instruction, 73, 101435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarides, R., Schiefele, U., Hettinger, K., & Frommelt, M. C. (2023). Tracing the signal from teachers to students: How teachers’ motivational beliefs longitudinally relate to student interest through student-reported teaching practices. Journal of Educational Psychology, 115(2), 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martínez, O., García-Jiménez, E., & Cuesta-Sáez-de-Tejada, J.-D. (2023). El bienestar emocional de los docentes como factor determinante en los procesos de enseñanza/aprendizaje en el aula. Estudios Sobre Educación, 44, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinauskas, R., & Malinauskiene, V. (2021). Training the social-emotional skills of youth school students in physical education classes. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 741195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardones-Soto, G. (2023). La influencia del clima escolar en el aprendizaje: Revisión sistemática. Revista Realidad Educativa, 3(2), 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martillo-Ortegano, B. G., Valverde-Velez, C. G., & Bastidas-Bolaños, C. M. (2023). High labor demand in the Contact Center of Guayaquil: Correlation between climate and work stress. Revista Científica Mundo de la Investigación y el Conocimiento, 7(1), 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Saura, H. F., Calderón, A., & Sánchez López, M. C. (2024). Programas de formación emocional inicial y permanente para docentes de Educación Infantil y Primaria: Una revisión sistemática. Revista Complutense de Educación, 35(1), 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M. P., López-Curbelo, M., & Fortes, D. (2019). Gender and psychological well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes-Rodrigues, L. T., Lago, E. C., Pinheiro-Landim, C. A., Pires-Ribeiro, I., & Vasconcelos-Mesquita, G. (2020). Estrés y depresión en docentes de una institución pública de enseñanza. Enfermería Global, 19(1), 209–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzón, L., Dávila, J., Rodríguez, E., & Pérez, A. (2023). La resiliencia en el contexto universitario, un estudio mixto exploratorio. Pensamiento Americano, 16(31), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S., Sofia-Roberto, M., Salgado-Pereira, N., Marques-Pinto, A., & Veiga-Simäo, A. M. (2021). Impacts of social and emotional learning interventions for teachers on teachers’ outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 677217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Cuenca, M., Ortiz-Cuenca, C., Chango-Unapucha, M. C., Cuenca-Barrera, C. E., & Ortiz-Cuenca, P. (2024). Factores que influyen en el estado emocional y desempeño de los docentes en la educación presencial. MENTOR Revista De investigación Educativa Y Deportiva, 3(7), 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachón-González, L. (2021). Estrés, tensión y fatiga por carga mental del trabajo. Gestión de la Seguridad y la Salud en el Trabajo, 2(1), 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Norambuena, S., Castelli-Correia, L. F., Venditti-Junior, R., & Silva-Junior, O. T. (2023). Autoeficacia en profesores de Educación Física chilenos de la región del Ñuble: Formación y desempeño profesional. Educación Física Y Ciencia, 25(1), e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinedo-Torres, N. P. (2023). Incidencia del bienestar docente en la calidad educativa. Gaceta de Pedagogía, 1(46), 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Rico, T., Gilar-Corbi, R., Izquierdo, A., & Castejón, J.-L. (2020). Teacher training can make a difference: Tools to overcome the impact of COVID-19 on Primary schools. an experimental study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Rico, T., Poveda, R., Gutiérrez-Fresneda, R., Castejón, J.-L., & Gilar-Corbi, R. (2023). Revamping teacher training for challenging times: Teachers’ well-being, resilience, emotional intelligence, and innovative methodologies as key teaching competencies. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Rico, T., & Sandoval, I. (2020). Can academic achievement in primary school students be improved through teacher training on Emotional Intelligence as a Key Academic Competency? Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas-Molero, P., Zurita-Ortega, F., Ubago-Jiménez, J. L., & González-Valero, G. (2019). Influence of emotional intelligence and burnout syndrome on teachers well-being: A systematic review. Social Sciences, 8(6), 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Trujillo, V., De Juanas-Oliva, A., & Rodríguez-Bravo, A. E. (2023). Factores asociados al bienestar psicológico de los docentes e implicaciones futuras: Una revisión sistemática. Revista de Psicología y Educación, 18(2), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, S., Núñez, J. C., Valle, A., Blas, R., & Rosario, P. (2009). Teachers’ self-efficacy, motivation and teaching strategies. Escritos de Psicología, 3(1), 1–7. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?pid=s1989-38092009000300001&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 11 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chávez, L., Fernández-Silano, M. G., Cantera-Artíguez, E., & Arocha-Marrero, C. (2024). Autoeficacia, burnout y bienestar psicológico docente desde la psicología positiva: Una aproximación con ecuaciones estructurales. Avances en Psicología, 32(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gómez, M., del Valle, S., Vega-Marcos, R., & Paniagua-Sánchez, D. (2018). Análisis de las creencias de los docentes en el desarrollo de su labor profesional. Indivisa Boletín de Estudios e Investigación, (18), 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, V. E., Carreño-Villavicencio, D. V., Quijije-Anchundia, P. J., & Aria-Arias, A. E. (2023). Estrés, ansiedad y desempeño laboral en docentes universitarios. South Florida Journal of Development, 4(8), 3047–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful ageing. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 12(1), 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M., Grau, R., & Martínez, I. M. (2005). Demandas laborales y conductas de afrontamiento: El rol modulador de la autoeficacia profesional. Psicothema, 17(3), 390–395. Available online: https://www.psicothema.com/pdf/3118.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2017). Social and emotional learning and teachers. The Future of Children, 27(1), 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanzione, I., Szpunar, G., & Femminini, A. (2024). Social and emotional skills for educational professionals success and work well-being. Form@re—Open Journal Per La Formazione in Rete, 24(1), 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täschner, J., Dicke, T., Reinhold, S., & Holzberger, D. (2024). “Yes, I Can!” A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies promoting teacher self-efficacy. Review of Educational Research, 20(10), 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, R., Valle, A., Rodríguez, S., Piñeiro, I., & Regueiro, B. (2020). Perceived stress and indicators of burnout in teachers at Portuguese higher education institutions (HEI). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2007). The differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(6), 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, S., Veiga-Branco, A., Rebelo, H., Afonso-Lourenço, A., & Cristóvão, A. M. (2020). The relationship between emotional intelligence ability and teacher efficacy. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(3), 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, C., & Hervás, G. (2009). La ciencia del bienestar: Fundamentos de una psicología positiva. Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y., Liu, Y., & Peng, J. (2024). Noticing the unnoticed: Teacher self-efficacy as a mediator between school context and teacher burnout in developing regions. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 28(2), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Levene | Control | Experimental | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | F | p | M (SD) | M (SD) | t (141) | p |

| Psychological well-being | ||||||

| Self-acceptance | 0.02 | 0.90 | 24.17 (6.74) | 22.89 (6.99) | 1.11 | 0.27 |

| Positive relationships | 8.81 | <0.001 | 27.87 (7.98) | 29.48 (5.27) | −1.41 | 0.16 |

| Autonomy | 0.00 | 0.99 | 35.69 (6.79) | 35.07 (6.64) | 0.55 | 0.58 |

| Environmental mastery | 0.01 | 0.91 | 23.77 (7.13) | 22.99 (7.26) | 0.65 | 0.52 |

| Personal growth | 0.00 | 0.95 | 27.61 (8.30) | 27.22 (8.11) | 0.29 | 0.77 |

| Purpose in life | 0.14 | 0.70 | 23.76 (7.18) | 23.11 (7.33) | 0.53 | 0.59 |

| Teacher self-efficacy | ||||||

| Instruction effectiveness | 0.10 | 0.75 | 14.87 (4.76) | 14.30 (4.58) | 0.73 | 0.46 |

| Adaptation teaching | 0.01 | 0.91 | 15.01 (4.74) | 13.96 (5.00) | 1.29 | 0.20 |

| Achievement motivation | 0.51 | 0.48 | 14.69 (4.94) | 14.16 (4.75) | 0.64 | 0.52 |

| Maintain discipline | 0.35 | 0.56 | 14.74 (4.77) | 14.16 (4.67) | 0.73 | 0.46 |

| Collaborate community | 0.42 | 0.52 | 14.87 (4.96) | 14.03 (4.82) | 1.03 | 0.30 |

| Cope with change | 0.04 | 0.83 | 14.59 (4.69) | 14.08 (4.82) | 0.63 | 0.53 |

| Variable | Source | SS | df | MS | F | p | η2 | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-acceptance | Intra | 231.98 | 1 | 231.98 | 20.43 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.99 |

| Intra × Gender | 0.73 | 1 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.800 | 0.00 | 0.06 | |

| Intra × Experience | 173.37 | 1 | 173.37 | 15.27 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.97 | |

| Intra × Inter | 1101.95 | 1 | 1101.95 | 97.05 | <0.001 | 0.41 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 1578.19 | 139 | 11.35 | |||||

| Gender | 8.75 | 1 | 8.75 | 0.20 | 0.652 | 0.00 | 0.07 | |

| Experience | 2734.90 | 1 | 2734.90 | 63.69 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 673.10 | 1 | 673.10 | 15.68 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.98 | |

| Error Inter | 5968.32 | 139 | 42.94 | |||||

| Positive relationships | Intra | 0.82 | 1 | 0.82 | 0.12 | 0.731 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Intra × Gender | 0.42 | 1 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.804 | 0.00 | 0.06 | |

| Intra × Experience | 51.04 | 1 | 51.04 | 7.40 | 0.007 | 0.05 | 0.77 | |

| Intra × Inter | 461.89 | 1 | 461.89 | 67.01 | <0.001 | 0.32 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 958.12 | 139 | 6.89 | |||||

| Gender | 12.20 | 1 | 12.20 | 0.25 | 0.615 | 0.00 | 0.08 | |

| Experience | 2718.60 | 1 | 2718.60 | 56.63 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 1467.19 | 1 | 1467.19 | 30.56 | <0.001 | 0.18 | 1.00 | |

| Error Inter | 6672.85 | 139 | 48.01 | |||||

| Autonomy | Intra | 290.85 | 1 | 290.85 | 28.33 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 1.00 |

| Intra × Gender | 0.30 | 1 | 0.30 | 0.03 | 0.865 | 0.00 | 0.05 | |

| Intra × Experience | 344.06 | 1 | 344.06 | 33.52 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 1.00 | |

| Intra × Inter | 928.98 | 1 | 928.98 | 90.50 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 1426.88 | 139 | 10.26 | |||||

| Gender | 0.65 | 1 | 0.65 | 0.02 | 0.893 | 0.00 | 0.05 | |

| Experience | 2699.38 | 1 | 2699.38 | 74.36 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 839.11 | 1 | 839.11 | 23.11 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 1.00 | |

| Error Inter | 5045.66 | 139 | 36.30 | |||||

| Environmental mastery | Intra | 300.27 | 1 | 300.27 | 25.89 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 1.00 |

| Intra × Gender | 4.76 | 1 | 4.76 | 0.41 | 0.523 | 0.00 | 0.10 | |

| Intra × Experience | 213.46 | 1 | 213.46 | 18.41 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 1.00 | |

| Intra × Inter | 878.48 | 1 | 878.48 | 75.75 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 1612.01 | 139 | 11.60 | |||||

| Gender | 0.24 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.941 | 0.00 | 0.05 | |

| Experience | 3259.09 | 1 | 3259.09 | 74.61 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 722.22 | 1 | 722.22 | 16.53 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.98 | |

| Error Inter | 6071.61 | 139 | 43.68 | |||||

| Personal growth | Intra | 234.91 | 1 | 234.91 | 16.85 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.98 |

| Intra × Gender | 9.19 | 1 | 9.19 | 0.66 | 0.418 | 0.00 | 0.13 | |

| Intra × Experience | 295.82 | 1 | 295.82 | 21.22 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 1.00 | |

| Intra × Inter | 1152.98 | 1 | 1152.98 | 82.70 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 1937.78 | 139 | 13.94 | |||||

| Gender | 12.37 | 1 | 12.37 | 0.27 | 0.635 | 0.00 | 0.08 | |

| Experience | 4707.24 | 1 | 4707.24 | 85.98 | <0.001 | 0.38 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 1224.89 | 1 | 1224.89 | 22.37 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 1.00 | |

| Error Inter | 7609.87 | 139 | 54.75 | |||||

| Purpose in life | Intra | 176.85 | 1 | 176.85 | 15.99 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.98 |

| Intra × Gender | 4.86 | 1 | 4.86 | 0.44 | 0.509 | 0.00 | 0.10 | |

| Intra × Experience | 258.61 | 1 | 258.61 | 23.39 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 1.00 | |

| Intra × Inter | 772.59 | 1 | 772.59 | 69.87 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 1536.95 | 139 | 11.06 | |||||

| Gender | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.02 | 0.896 | 0.00 | 0.05 | |

| Experience | 3234.90 | 1 | 3234.90 | 74.15 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 684.25 | 1 | 684.25 | 15.68 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.98 | |

| Error Inter | 6064.00 | 139 | 43.63 |

| Variable | Source | SS | df | MS | F | p | η2 | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instruction effectiveness | Intra | 183.78 | 1 | 183.78 | 32.52 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 1.00 |

| Intra × Gender | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.00 | 0.05 | |

| Intra × Experience | 109.64 | 1 | 109.64 | 19.40 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.99 | |

| Intra × Inter | 977.94 | 1 | 977.94 | 173.06 | <0.001 | 0.55 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 185.48 | 139 | 5.65 | |||||

| Gender | 0.89 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.05 | 0.828 | 0.00 | 0.055 | |

| Experience | 1093.60 | 1 | 1093.60 | 58.06 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 826.08 | 1 | 826.08 | 43.85 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 1.00 | |

| Error Inter | 2618.35 | 139 | 18.84 | |||||

| Adaptation teaching | Intra | 159.72 | 1 | 159.72 | 24.18 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.998 |

| Intra × Gender | 0.97 | 1 | 0.97 | 0.15 | 0.701 | 0.00 | 0.067 | |

| Intra × Experience | 106.75 | 1 | 106.75 | 16.16 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.979 | |

| Intra × Inter | 1243.18 | 1 | 1243.18 | 188.23 | <0.001 | 0.57 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 918.04 | 139 | 6.60 | |||||

| Gender | 3.395 | 1 | 3.39 | 0.17 | 0.680 | 0.00 | 0.07 | |

| Experience | 1286.11 | 1 | 1286.11 | 64.74 | <0.001 | 0.32 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 825.17 | 1 | 825.168 | 41.54 | < 0.001 | 0.23 | 1.00 | |

| Error Inter | 2761.33 | 139 | 19.87 | |||||

| Achievement motivation | Intra | 180.02 | 1 | 180.02 | 32.62 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 1.00 |

| Intra × Gender | 1.62 | 1 | 1.62 | 0.295 | .588 | 0.00 | 0.08 | |

| Intra × Experience | 151.57 | 1 | 151.57 | 27.47 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 1.00 | |

| Intra × Inter | 973.23 | 1 | 973.23 | 176.37 | <0.001 | 0.56 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 767.01 | 139 | 5.52 | |||||

| Gender | 7.39 | 1 | 7.39 | 0.35 | 0.554 | 0.00 | 0.091 | |

| Experience | 1158.96 | 1 | 1158.96 | 55.13 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 849.73 | 1 | 849.73 | 40.42 | <0.001 | 0.22 | 1.00 | |

| Error Inter | 2921.82 | 139 | 21.02 | |||||

| Maintain discipline | Intra | 145.59 | 1 | 145.59 | 25.02 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 1.00 |

| Intra × Gender | 6.72 | 1 | 6.72 | 1.15 | 0.284 | 0.01 | 0.19 | |

| Intra × Experience | 140.01 | 1 | 140.01 | 24.06 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 1.00 | |

| Intra × Inter | 991.69 | 1 | 991.69 | 170.40 | <0.001 | 0.55 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 808.94 | 139 | 5.82 | |||||

| Gender | 0.04 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.961 | 0.00 | 0.05 | |

| Experience | 1101.22 | 1 | 1101.22 | 57.78 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 837.05 | 1 | 837.05 | 43.92 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 1.00 | |

| Error Inter | 2649.05 | 139 | 19.06 | |||||

| Collaborate community | Intra | 163.54 | 1 | 163.54 | 26.78 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 1.00 |

| Intra × Gender | 0.62 | 1 | 0.62 | 0.10 | 0.751 | 0.00 | 0.06 | |

| Intra × Experience | 101.34 | 1 | 101.34 | 16.59 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.98 | |

| Intra × Inter | 1210.21 | 1 | 1210.21 | 198.18 | <0.001 | 0.59 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 848.81 | 139 | 6.11 | |||||

| Gender | 0.11 | 1 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.942 | 0.00 | 0.05 | |

| Experience | 1325.97 | 1 | 1325.97 | 60.80 | <0.001 | 0.30 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 905.80 | 1 | 905.80 | 41.54 | <0.001 | 0.23 | 1.00 | |

| Error Inter | 3031.27 | 139 | 21.81 | |||||

| Cope with change | Intra | 206.89 | 1 | 206.89 | 36.23 | <0.001 | 0.21 | 1.00 |

| Intra × Gender | 0.13 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.880 | 0.00 | 0.05 | |

| Intra × Experience | 113.68 | 1 | 113.68 | 19.91 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.99 | |

| Intra × Inter | 1103.95 | 1 | 1103.95 | 193.33 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 1.00 | |

| Error Intra | 793.70 | 139 | 5.71 | |||||

| Gender | 13.63 | 1 | 13.63 | 0.73 | 0.394 | 0.00 | 0.136 | |

| Experience | 1189.44 | 1 | 1189.44 | 63.91 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 1.00 | |

| Inter | 978.58 | 1 | 978.58 | 52.58 | <0.001 | 0.27 | 1.00 | |

| Error Inter | 2586.78 | 139 | 18.61 |

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Experimental | Control | Experimental | |||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Psychological well-being | ||||||||

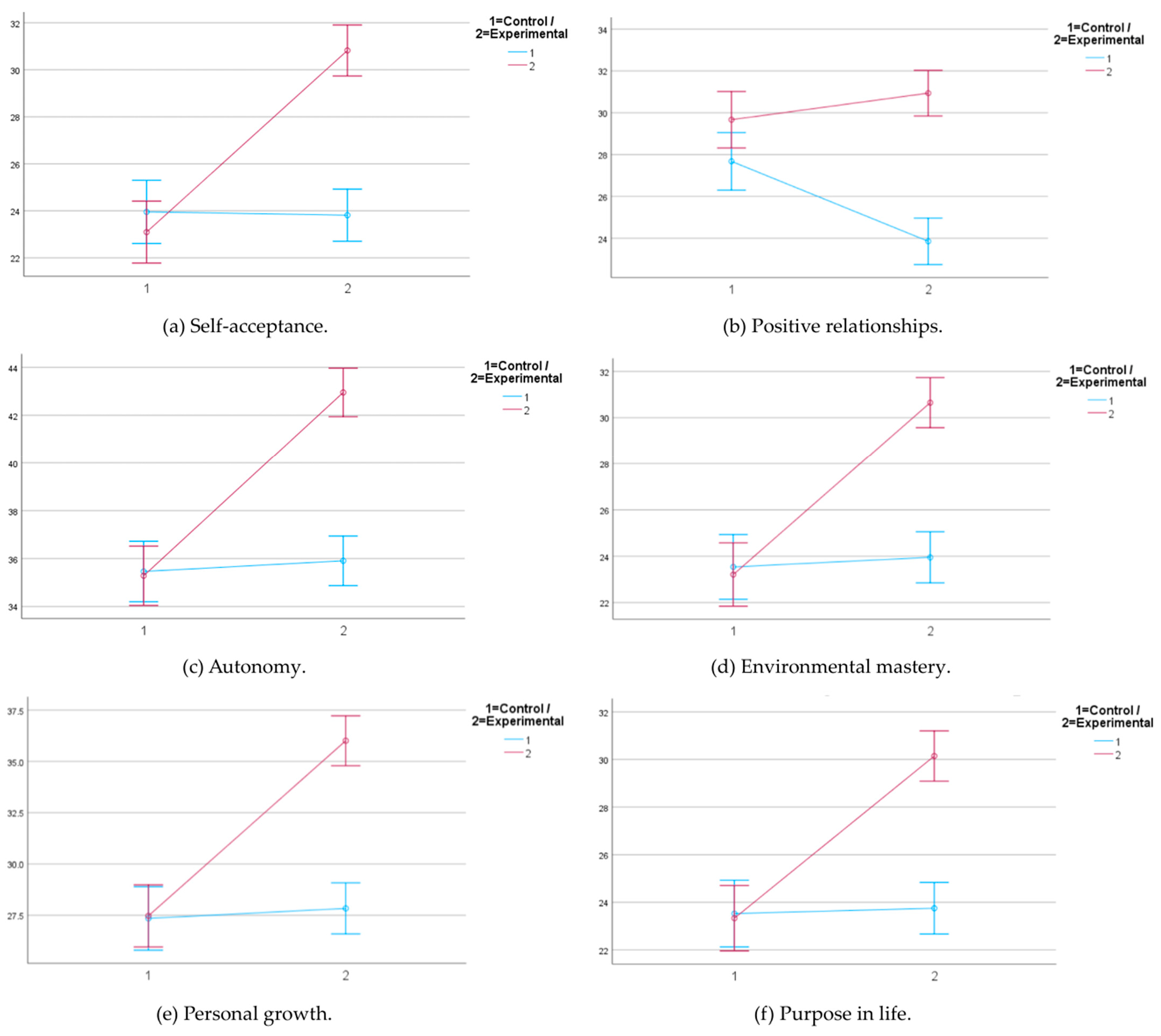

| Self-acceptance | 24.17 | 6.74 | 22.89 | 6.99 | 23.94 | 7.07 | 30.70 | 2.28 |

| Positive relationships | 27.87 | 7.98 | 29.48 | 5.27 | 24.00 | 7.32 | 30.79 | 2.12 |

| Autonomy | 35.69 | 6.79 | 35.07 | 6.64 | 36.01 | 6.58 | 42.85 | 1.53 |

| Environmental mastery | 23.77 | 7.13 | 22.99 | 7.26 | 24.09 | 7.10 | 30.52 | 2.30 |

| Personal growth | 27.61 | 8.30 | 27.22 | 8.11 | 28.00 | 8.14 | 35.85 | 2.63 |

| Purpose in life | 23.76 | 7.18 | 23.11 | 7.33 | 23.89 | 6.85 | 30.01 | 2.45 |

| Teacher self-efficacy | ||||||||

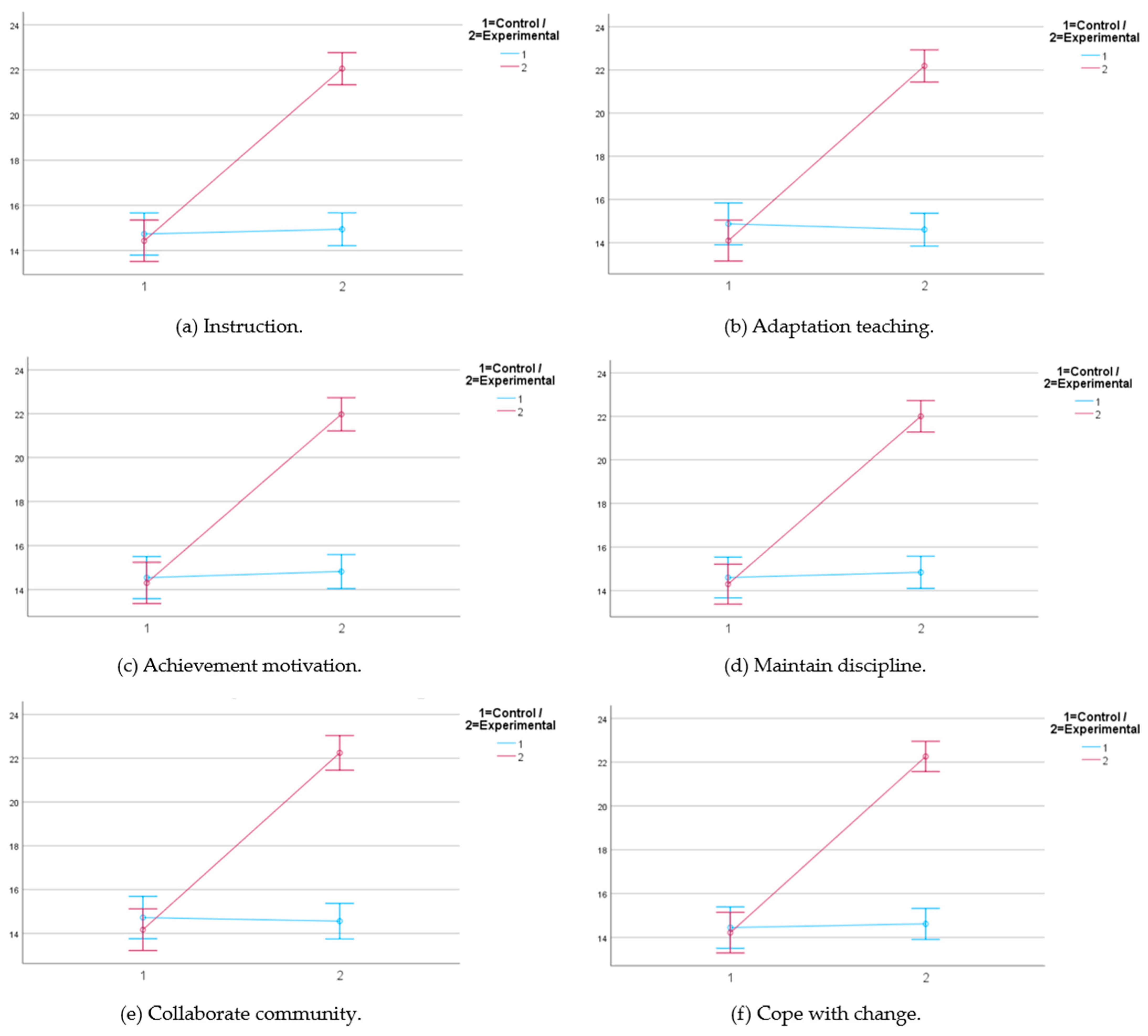

| Instruction effectiveness | 14.87 | 4.76 | 14.30 | 4.58 | 15.01 | 4.62 | 21.99 | 0.96 |

| Adaptation teaching | 15.01 | 4.74 | 13.96 | 4.99 | 14.69 | 4.89 | 22.11 | 1.03 |

| Achievement motivation | 14.69 | 4.94 | 14.16 | 4.75 | 14.89 | 4.86 | 21.90 | 0.96 |

| Maintain discipline | 14.74 | 4.77 | 14.16 | 4.67 | 14.91 | 4.67 | 21.93 | 0.93 |

| Collaborate community | 14.87 | 4.96 | 14.03 | 4.82 | 14.64 | 5.19 | 22.16 | 1.04 |

| Cope with change | 14.59 | 4.69 | 14.08 | 4.82 | 14.69 | 4.55 | 22.19 | 1.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Izquierdo, A.; Pozo-Rico, T.; Pérez-Rico, C.; Fernández-García, C.; Castejón, J.-L.; Gilar-Corbi, R. Effectiveness of a Training Program on the Psychological Well-Being and Self-Efficacy of Active Teachers, Controlling for Gender and Experience. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030382

Izquierdo A, Pozo-Rico T, Pérez-Rico C, Fernández-García C, Castejón J-L, Gilar-Corbi R. Effectiveness of a Training Program on the Psychological Well-Being and Self-Efficacy of Active Teachers, Controlling for Gender and Experience. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030382

Chicago/Turabian StyleIzquierdo, Andrea, Teresa Pozo-Rico, Cristina Pérez-Rico, Carlos Fernández-García, Juan-Luis Castejón, and Raquel Gilar-Corbi. 2025. "Effectiveness of a Training Program on the Psychological Well-Being and Self-Efficacy of Active Teachers, Controlling for Gender and Experience" Education Sciences 15, no. 3: 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030382

APA StyleIzquierdo, A., Pozo-Rico, T., Pérez-Rico, C., Fernández-García, C., Castejón, J.-L., & Gilar-Corbi, R. (2025). Effectiveness of a Training Program on the Psychological Well-Being and Self-Efficacy of Active Teachers, Controlling for Gender and Experience. Education Sciences, 15(3), 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030382