Cognitive-Dissonance-Based Educational Methodological Innovation for a Conceptual Change to Increase Institutional Confidence and Learning Motivation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of the Educational Theory for the Topic

1.2. Philosophical Analysis of the Topicality of the Subject

2. Literary Analysis

2.1. Education Governance and Policy Issues

2.2. Educational Technology Issues

3. Methodology

3.1. Background and Description of the Research Environment

3.2. Qualitative Methods

3.2.1. Industry Interviews and Analysis

3.2.2. Management Interviews and Preference Analysis

3.2.3. Short-Cycle Training and Preference Correction

3.3. Quantitative Methods for Measuring Preferences and the Need for Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Innovation Preferences Before and After Training

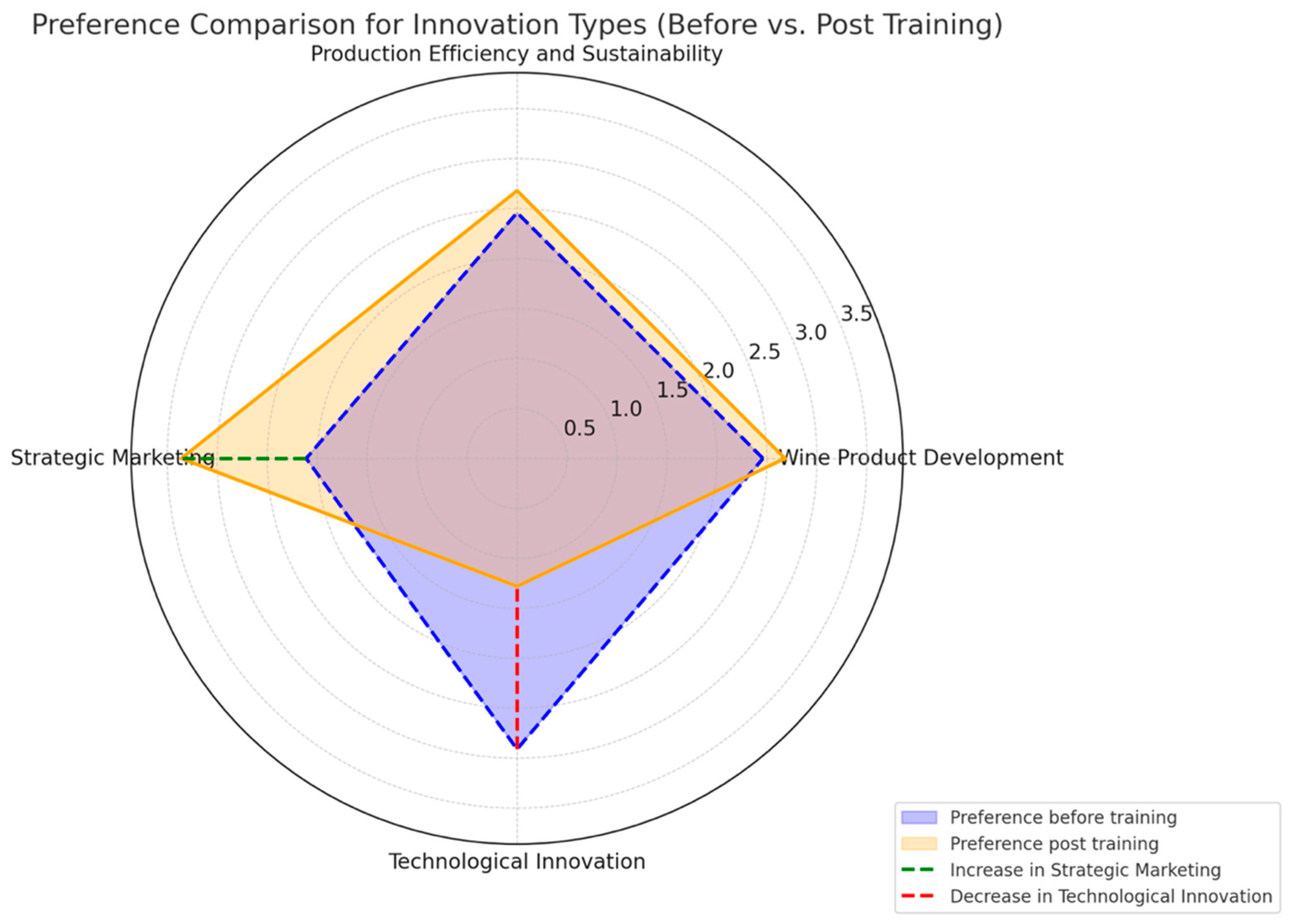

- Strategic Marketing: participants noted a newfound appreciation for the relevance of marketing strategies to their business goals. One respondent commented the following: “I had not considered how essential strategic marketing is to align our products with market demands. This training changed my perspective entirely”.

- Technological Innovation: interviews revealed that the decreased preference for technological innovation was not a rejection of its importance but rather an adjustment towards a balanced perspective. As one participant explained the following: “We now see technology as part of a broader innovation strategy rather than the sole focus”.

- Operational and Sustainability Focus: participants highlighted how the training encouraged them to reevaluate their priorities. One manager remarked the following: “Sustainability initiatives seemed less urgent before, but now I recognize their long-term value in enhancing production efficiency”.

- -

- The blue line represents the pre-training preference values, which illustrate the baseline in each dimension.

- -

- The yellow line shows the change in post-training preferences, which reflects the results of the shifts.

- -

- The green dashed line highlights the increase in the strategic marketing preference. This innovation dimension shows one of the most significant positive shifts and reflects the targeted effectiveness of training in this area.

- -

- The red dashed line highlights the declining preference for technological innovation. This decrease may be the result of a reallocation of resources and attention, reflecting a shift in the focus of training.

- -

- The shape of the spider web diagram shows significant variations. The difference between the pre- and post-training lines visually highlights the shift in preferences.

- -

- The dimensions of strategic marketing and wine product development show a greater territorial growth, indicating that participants in these areas are better aligned with industry expectations.

- -

- The narrowing of the field in the technological innovation dimension confirms the decline in preferences, while the dimension of production efficiency and sustainability remains essentially unchanged, indicating stability in this area.

- -

- Starting from the center of Figure 2, it is clear that preferences varied across dimensions. The visual indication of the direction of change (increase or decrease) facilitates data analysis, while the colors and dashed lines clearly distinguish between positive and negative trends.

- -

- An increase in the strategic marketing dimension emphasizes the effectiveness of training, while a decrease in technological innovation indicates an understanding that the innovation focus has become more aligned with industry needs.

- -

- The advantage of the spider web diagram is that it can illustrate both the relative values of preferences and their shift over time. The spatial shifts in the graph intuitively reflect the shift in preferences as a result of training.

- -

- The different color coding and line styles ensure that changes are clearly distinguishable, making it easier to quickly interpret and present trends.

- Product Development—Strategic Marketing (H = 5.104, p = 0.024)

- Production Efficiency—Strategic Marketing (H = 4.573, p = 0.033)

- Strategic Marketing—Technological Innovation (H = 6.291, p = 0.012)

4.2. Achievement of Training Objectives and Long-Term Impacts

4.3. Evaluation of Hypotheses Based on the Results

4.3.1. Significance of the Results

4.3.2. Generalizability of the Results

5. Discussion

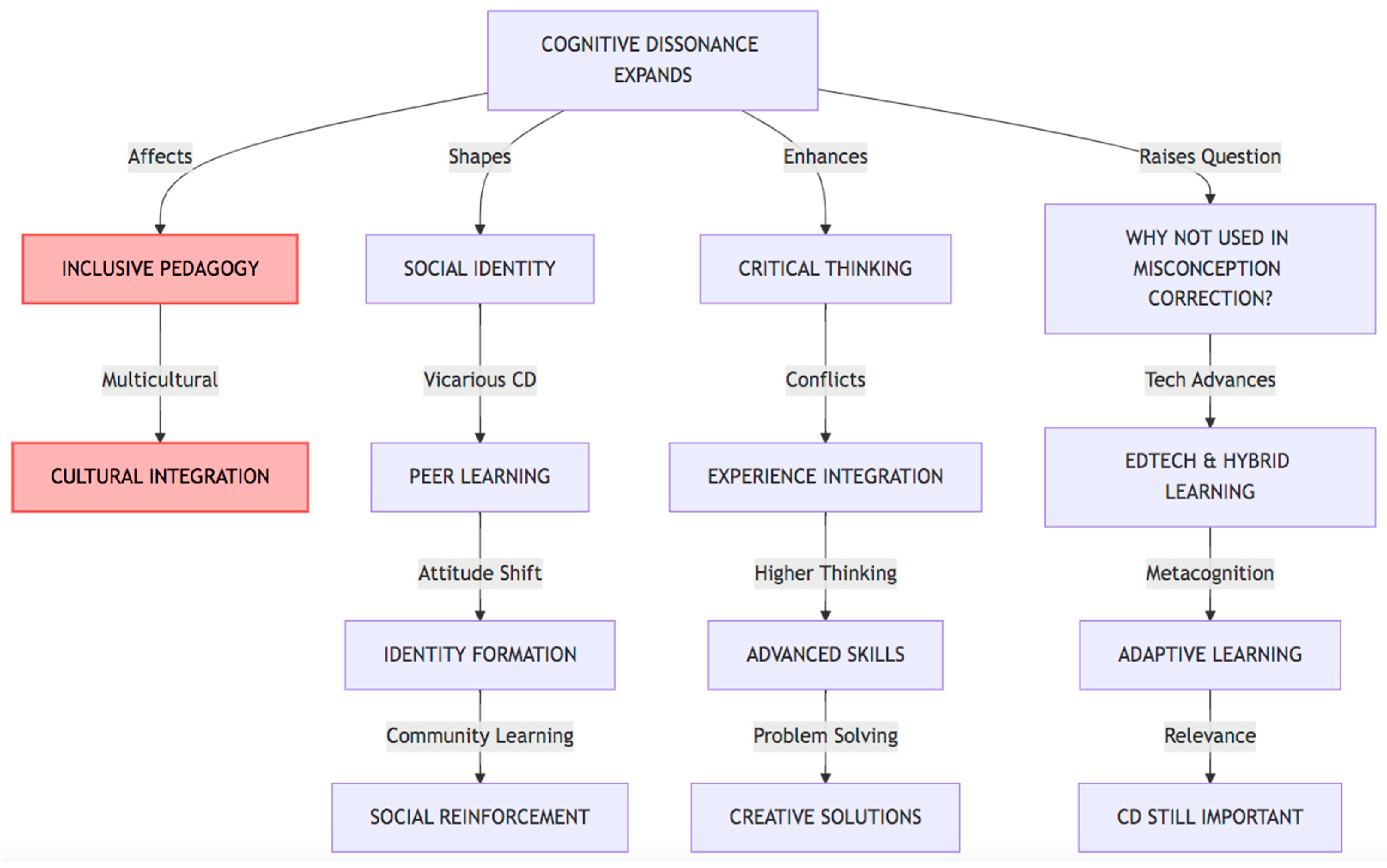

5.1. Dilemmas of the Theoretical Framework

- Diagnostic teaching methods: these methods help teachers to uncover students’ misconceptions, allowing them to target conceptual misunderstandings. They are particularly important in inclusive education as they support teachers in understanding learners’ starting points and designing effective interventions. In this way, they contribute to the effectiveness of the learning process and to the development of correct understanding (Kopmann, 2022).Inducing cognitive conflict: CDT-based methods aim to confront learners with their own misconceptions, encouraging them to re-evaluate their thinking. This can often be achieved through experimentation, by presenting real problems that highlight the gaps in misconceptions and help to develop more accurate knowledge. As Thomas and Kirby (2020) established, situational interest and cognitive conflict can be effective tools for helping learners recognize their own faulty thinking patterns and facilitating deeper learning processes. Furthermore, according to T. Brown (2018), “Cognitive dissonance-based teaching strategies help students learn at a deeper, conceptual level while strengthening their critical thinking skills”.

- Reflective reinforcement: techniques to make students aware of their thinking processes and newly acquired concepts, and to encourage reflection. Reflective reinforcement helps learners to better understand the differences between correct and incorrect concepts, thereby developing deeper and more sustainable knowledge. As Lopez and Carter (2019) emphasize, “Reflective practices not only reinforce current learning, but also support long-term cognitive development by enabling learners to apply their existing knowledge in new situations”. Furthermore, according to Singh and Patel (2021), “Encouraging self-reflection is key to developing independent learning skills and promotes deeper student engagement in the learning process”.

5.2. Practical Implications and Solutions

5.3. Definition of the Training Methodology

5.4. Research and Experiment Implementation

5.4.1. Introduction to the Training Program

5.4.2. Efficiency Evaluation

5.4.3. More Training and Participant Feedback

6. Conclusions

6.1. Proposals for Education Policy and Curriculum Innovation

6.2. The Applicability of the Methodology in Different Contexts

6.3. Synthesis and Practical Recommendations

7. Limitations

7.1. Sample and Sectoral Restrictions

7.2. Lack of Analysis of Long-Term Effects

7.3. Methodological Issues

7.4. Individual Adaptability

7.5. Possibility of Wider Adaptation

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdalina, L., Bulatova, E., Gosteva, S., Kunakovskaya, L., & Frolova, O. A. (2022). Professional development of teachers in the context of the lifelong learning model: The role of modern technologies. World Journal on Educational Technology, 14(1), 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A., Blackwell, M., & Sen, M. (2018). Explaining preferences from behavior: A cognitive dissonance approach. American Journal of Political Science, 62(4), 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, L., Hosseini, M., & Abbasi, M. (2021). Ethical considerations in educational research. Journal of Educational Ethics, 18(1), 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Anisimova, A. E. (2014). The future of education based on planning needs in labor force in the USA and the UK regions. International Education Studies, 7(6), 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabidze, L. (2021). Modern trends in development of winemaking. Economics, 104(3–5), 202101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artz, G. M., Guo, Z., & Orazem, P. F. (2018). Location, location, location: Place-specific human capital, rural firm entry and firm survival. In R. J. Stimson (Ed.), New advances in regional economics and research (pp. 173–191). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Beloedova, A. V., & Tyazhlov, Y. (2023). Scientific text on the Internet: Communication-typological characteristics. Scientific Knowledge Online. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377921437 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Borsos, L., & Kruzslicz, T. (2022). Digital teaching solutions in teaching Hungarian as a foreign language—Lessons from distance learning in the wake of the COVID-19 epidemic. Modern Language Teaching, 1–2, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. (2018). Using cognitive dissonance to foster critical thinking in the classroom. Critical Thinking in Education Quarterly, 22(3), 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Busher, H., & Fox, A. (2020). The amoral academy? A critical discussion of research ethics in the neo-liberal university. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 39(2), 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela-Borja, Y. M., Intriago-Loor, M. E., Solórzano-Coello, D. L., & Rodríguez-Gámez, M. (2020). Los procesos motivacionales de la teoría cognitiva social y su repercusión en el aprendizaje de los estudiantes de bachillerato. Dominio de las Ciencias, 6(3), 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. K. H., & Hume, A. (2019). Towards a consensus model: Literature review of how science teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge is investigated in empirical studies. In Repositioning pedagogical content knowledge in teachers’ knowledge for teaching science (pp. 1–18). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa Rêgo, L., Santiago, A. N., Campos, T. A. M., & Rodrigues, M. A. C. (2023). Influência da autoestima na manutenção da motivação no processo de aprendizagem. Revista Cognitionis, 6(2), 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C. D., & Araujo-Oliveira, A. (2021). Métacognition, états affectifs et engagement cognitif chez des étudiants universitaires: Triade percutante pour l’apprentissage et l’inclusion. Education Journal, 23(1), 8602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejeu, V., Dejeu, P., Muresan, A., & Bradea, P. (2025). Bone composition changes and calcium metabolism in obese adolescents and young adults undergoing sleeve gastrectomy: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sá, L. T. F., & Henrique, A. (2019). A triangulação na pesquisa científica em educação. Praxis Educacional, 15(36), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, A. K., & Peyrefitte, J. (2022). Investigation of innovation in wine industry via meta-analysis. Wine Business Case Research Journal, 5(1), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draycott, S., & Dabbs, A. (1998). Cognitive dissonance and motivational interviewing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M. (2022). Innovation management in wine business—Need to address front-end, back-end, or both? Wine Business Case Research Journal, 5(1), 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigon, A., Doloreux, D., & Shearmur, R. (2020). Drivers of eco-innovation and conventional innovation in the Canadian wine industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 275, 124115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C. B., & Birkinshaw, J. (2019). The hierarchical erosion effect: A new perspective on perceptual differences and business performance. Journal of Management Studies, 56(7), 1231–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2008). Diverse economies: Performative practices for other worlds. Progress in Human Geography, 32(5), 613–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouin, M.-M., Denis, C., Lefebvre, N., Lanctôt, S., & Bélisle, M. (2022). Favoriser l’alignement pédagogique lors d’une migration en formation à distance: Une Démarche SoTL. OTESSA Conference Proceedings, 2(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillitsch, M., & Asheim, B. (2018). Place-based innovation policy for industrial diversification in regions. European Planning Studies, 26(8), 1638–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutić, T., Stević, F., & Labak, I. (2023). Peer teaching as support for the use of concept maps in independent online learning. Educational Innovations, 9(2), 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, E. (2019). Embracing a culture of lifelong learning—In universities & all spheres of life. Journal of Lifelong Learning, 18(1), 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, N., Muthmainah, & Wulandari, R. (2022). Children’s online cognitive learning through integrated technology and hybrid learning. Journal of Pedagogy and Early Development, 16(1), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hußner, I., Lazarides, R., Symes, W., Richter, E., & Westphal, A. (2023). Reflect on your teaching experience: Systematic reflection of teaching behaviour and changes in student teachers’ self-efficacy for reflection. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 26, 1301–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifrianti, S. (2018). Membangun kompetensi pedagogik dan keterampilan dasar mengajar bagi mahasiswa melalui lesson study. Terampil: Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pembelajaran Dasar, 5(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikävalko, M., Sointu, E., Lambert, M., & Viljaranta, J. (2022). Students’ self-efficacy in self-regulation together with behavioural and emotional strengths: Investigating their self-perceptions. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 37(5), 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S. Y., & Ivanova, D. V. (2021). Education as an institutional factor of social change. Journal of Sociological Research, 7(4), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R. (2019). Inclusive pedagogy: Tapping cognitive dissonance experienced by international students. Writing & Pedagogy, 11(1), 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaubert, M., Girandola, F., & Souchet, L. (2020). Cognitive dissonance and social identity in educational contexts. European Review of Social Psychology, 31(1), 46–79. [Google Scholar]

- John, C. A. (2021). Cognitive dissonance in Nella Larsen’s Passing. Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association, 53(2), 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafatis, S. P., Ledden, L., Riley, D., & Singh, J. (2016). The added value of brand alliances in higher education. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3237–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D. P., Kumar, A., Dutta, R., & Malhotra, S. (2022). The role of interactive and immersive technologies in higher education: A survey. Journal of Engineering Education and Technology, 36(2), 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopmann, H. (2022). Diagnostic teaching methods in inclusive education: Teacher perspectives and conceptual misunderstandings. Educational Studies Journal, 48(2), 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Krajcik, J., McNeill, K. L., & Reiser, B. J. (2008). Learning-goals-driven design model: Developing curriculum materials that align with national standards and incorporate project-based pedagogy. Science Education, 92(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, I. T. (2023). Structural relationship among educational service quality, self-directed learning ability, and learning flow recognized by lifelong education college students: The moderating effect of adult learner characteristics. Journal of Educational Research, 21(4), 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepinoy, A., Vanderlinde, R., & Lo Bue, S. (2023). Emergency remote teaching, students’ motivation and satisfaction of their basic psychological needs in higher education. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1187251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, O., Taylor, S., Boyacigiller, N. A., & Bodner, T. E. (2015). Perceived senior leadership opportunities in MNCs: The effect of social hierarchy and capital. Journal of World Business, 50(4), 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M., & Carter, P. (2019). Reflective practices in education: Bridging theoretical understanding and practical application. Journal of Educational Development, 28(1), 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lungu, V. (2022). Prospective pedagogy: Conceptual and methodological fundamentals. European Journal of Education, 58(4), 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, C., & Calzone, S. (2022). Spazi di apprendimento virtuali e integrati: L’esperienza di alcune scuole italiane impegnate nei progetti ‘PON per la scuola’. IUF Research, 3(6), 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdiarmid, G., & Zhao, Y. (2022). Time to rethink: Educating for a technology-transformed world. Educational Research Journal, 36(4), 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, N. B., & Yan, Z. (2021). Involved and autonomy-supportive teachers make reflective students: Linking need-supportive teacher practices to student self-assessment practices. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molcsanyak, O., & Borzik, O. (2019). Study of key aspects of implementing innovations in higher education institutions. Education and Human Studies, 1, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoasong, M. Z. (2022). Curriculum adaptation for blended learning in resource-scarce contexts. Journal of Management Education, 46(3), 456–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, N. F. (2016). Market-led strategic change: Transforming the process of going to market (4th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornpongtechavanich, P., & Wannapiroon, P. (2021). Intelligent interactive learning platform for seamless learning ecosystem to enhance digital citizenship’s lifelong learning. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 16(14), 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M., Nottis, K., Vigeant, M., Kim, C., & Jablonski, E. (2016, June 26–29). The effect of course type on engineering undergraduates’ situational motivation and curiosity. ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rofiq, S. K. (2023). Penerapan model pembelajaran attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction untuk mengembangkan hasil belajar. Ambarsa, 3(1), 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas Baños, M. (2017). Desarrollo económico vs. sustentabilidad fuerte: Los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje de una educación para el Siglo XXI. Revista de Educación y Desarrollo, 8(4), 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlberg, P., & Oldroyd, D. (2010). Pedagogy for economic competitiveness and sustainable development. European Journal of Education, 45(2), 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, S. (2021). Upaya peningkatan kompetensi penggunaan WhatsApp sebagai media pembelajaran jarak jauh melalui In House Training. Jurnal Komunikasi, 5(1), 1282–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. N., & Parvatiyar, A. (2021). Sustainable marketing: Market-driving, not market-driven. SAGE Open, 11(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., & Patel, K. (2021). Enhancing self-directed learning through reflective reinforcement techniques. Journal of Advanced Educational Research, 42(5), 321–336. [Google Scholar]

- Stolk, J., Zastavker, Y., & Gross, M. D. (2018, June 23–July 27). Gender, motivation, and pedagogy in the STEM classroom: A quantitative characterization. Proceedings of ASEE Annual Conference (p. 30556), Salt Lake City, UT, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J., & Cooper, J. (2001). A self-standards model of cognitive dissonance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(3), 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, K. (2020). A study on national education policy 2020 regarding career opportunities. Shanlax International Journal of Economics, 9(1), 3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungurova, N. (2021). Self-trust and academic motivation of students in virtual educational space. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 196, 15405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijs, A., & Van Den Akker, J. (2009). Curriculum in development. SLO. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C. L., & Kirby, L. A. J. (2020). Situational interest helps correct misconceptions: An investigation of conceptual change in university students. Instructional Science, 48(5), 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinea, M. (2019). Rethinking Teacher Training According to 21st Century Competences. European Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 4(3), 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waye, V., Rocca, L., Veneziani, M., Helliar, C., & Suryawathy, I. (2022). Policy, regulation, and institutional approaches to digital innovation in the wine sector: A cross-country comparison. British Food Journal, 125(5), 1854–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovleva, O., & Kushnir, O. (2021). Implementation of SDGs in higher education institutions as a key stage in the development of modern education. Herald of Kyiv National University of Culture and Arts, 48, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B., & Nie, J. (2021). The transformation of higher education under the concept of lifelong education. Advances in Higher Education, 4(12), 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yucedal, H. M. (2022). learning strategies in lifelong learning. International Journal of Social Science Research and Review, 5(9), 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Innovation Type | Preferences Before Training | Preferences Post Training |

|---|---|---|

| Product Development | 2.46 | 2.68 |

| Production Efficiency and Sustainability | 2.46 | 2.68 |

| Strategic Marketing | 2.11 | 3.36 |

| Technological Innovation | 2.91 | 1.28 |

| Pair | Kruskal-Wallis H Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Product Development—Production Efficiency | 0.174 | 0.678 |

| Product Development—Strategic Marketing | 5.104 | 0.024 |

| Product Development—Technological Innovation | 3.206 | 0.074 |

| Production Efficiency—Strategic Marketing | 4.573 | 0.033 |

| Production Efficiency—Technological Innovation | 1.984 | 0.159 |

| Strategic Marketing—Technological Innovation | 6.291 | 0.012 |

| Method | Promoting a Change of Mindset | Increasing Motivation to Learn | Correction of Erroneous Views | Practical Feasibility | Aggregate Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive dissonance induction | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 19 |

| Activating prior knowledge | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 13 |

| Reflective learning | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 15 |

| Developing critical thinking | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 14 |

| Conflict-based learning | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Köpeczi-Bócz, T. Cognitive-Dissonance-Based Educational Methodological Innovation for a Conceptual Change to Increase Institutional Confidence and Learning Motivation. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030378

Köpeczi-Bócz T. Cognitive-Dissonance-Based Educational Methodological Innovation for a Conceptual Change to Increase Institutional Confidence and Learning Motivation. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):378. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030378

Chicago/Turabian StyleKöpeczi-Bócz, Tamás. 2025. "Cognitive-Dissonance-Based Educational Methodological Innovation for a Conceptual Change to Increase Institutional Confidence and Learning Motivation" Education Sciences 15, no. 3: 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030378

APA StyleKöpeczi-Bócz, T. (2025). Cognitive-Dissonance-Based Educational Methodological Innovation for a Conceptual Change to Increase Institutional Confidence and Learning Motivation. Education Sciences, 15(3), 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030378