Technology-Enhanced Language Learning: Subtitling as a Technique to Foster Proficiency and Intercultural Awareness

Abstract

1. Introduction

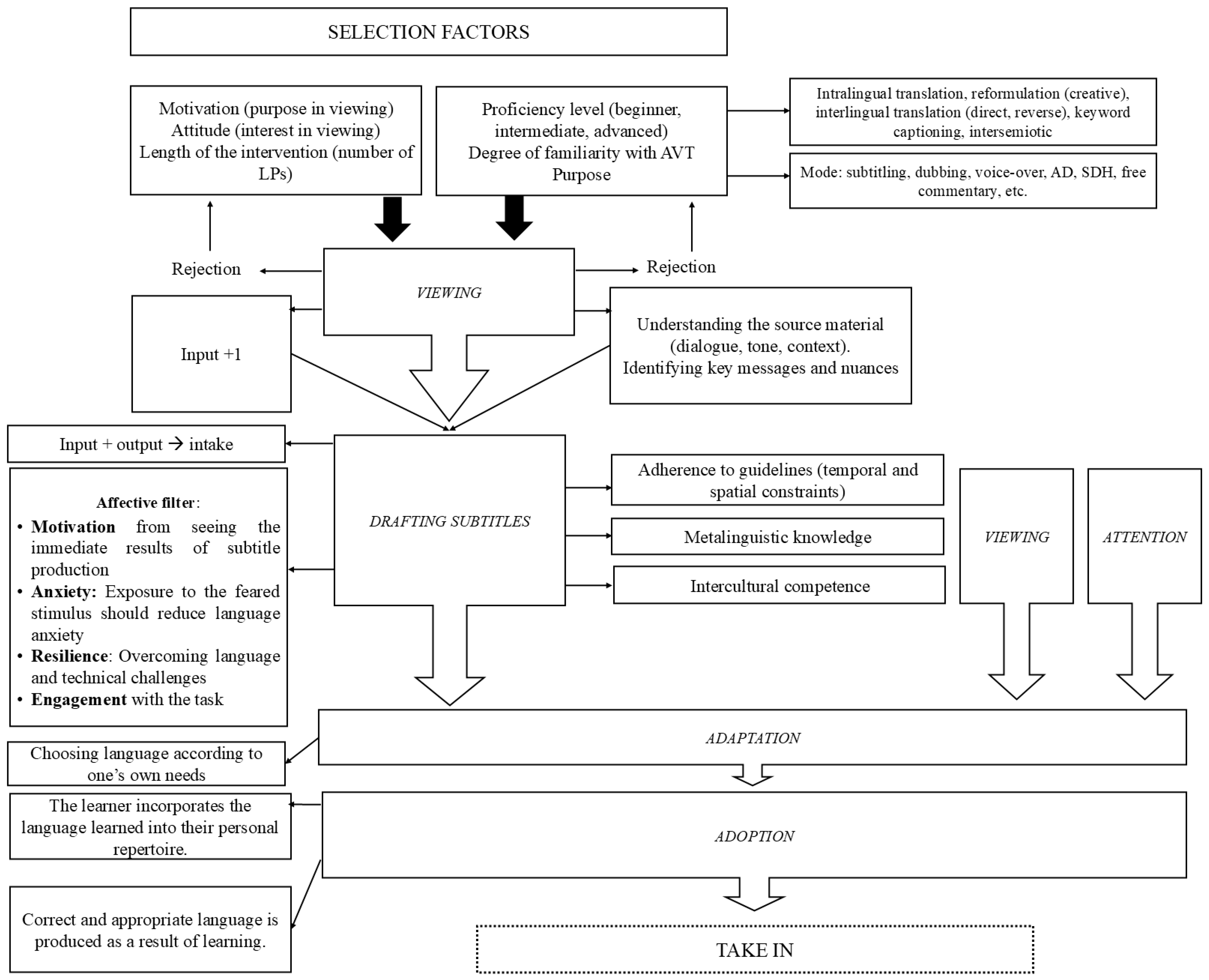

- Warm-up: This is the first stage of the lesson plan. It should include oral and written reception tasks related to the video, which has been specifically chosen for the lesson plan, as well as exercises about grammar or vocabulary to reinforce these aspects.

- Video viewing: In this second stage, learners are shown the video, and they should answer a set of questions to ensure they have fully understood the contents of the video they would later be asked to translate. It is important to note that the video should not last more than 2 min.

- DAT task: This is the most challenging stage of the lesson plan, as students are expected to undertake their own translation of a 1 min excerpt retrieved from the video they viewed in the second stage, according to the AVT mode (subtitling, voice-over, dubbing, AD, SDH or free commentary) and the language combination established by the teacher (keyword captioning, interlingual, intralingual or creative). Stages 1 (warm-up) and 2 (video viewing) are essential for completing this task, as they provide the specific scaffolding needed for students to produce their translation.

- Post-DAT task: This final stage aims to consolidate the new knowledge through a mediation task. If the DAT task involves captioning, the task should include mediation and oral production. For DAT tasks based on revoicing, this final stage should involve mediation and written production.

1.1. Didactic Subtitling: Educational Background

1.2. Didactic Subtitling: State of the Art

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Important Considerations on the Implementation of the Intervention

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Materials

- Mary Shelley (https://www.tradilex.es/secuencias/27/lessons/75, accessed on 2 September 2024);

- Emily Dickinson (https://www.tradilex.es/secuencias/27/lessons/76, accessed on 2 September 2024);

- Jane Austen (https://www.tradilex.es/secuencias/27/lessons/77, accessed on 2 September 2024);

- Virginia Woolf (https://www.tradilex.es/secuencias/27/lessons/78, accessed on 2 September 2024).

2.4. Schedule

- Week 1: Participants were asked to complete the language skills test, which was administered in a paper-based format in a controlled environment; they also were asked to fulfill the ERI scale.

- Week 2: The participants completed a lesson plan on Mary Shelley. The objectives included developing audiovisual mediation and reception, improving written production, deepening lexical and grammatical aspects such as conditional sentences and reported speech and fostering sensitivity towards motherhood from a feminist perspective. The structure consisted of a warm-up with five exercises, a critical viewing of a film scene followed by a short-written reflection, creating their own English subtitles and a consolidation task requiring a 250–300-word essay imagining the life of a hypothetical sister of Shakespeare.

- Week 3: The participants engaged in a lesson plan centered on Emily Dickinson, aimed at enhancing audiovisual mediation and reception skills. The lesson plan also sought to improve written expression, consolidate grammatical elements like conditional sentences and foster an understanding of the underrepresentation of certain groups in the literary canon, including non-heteronormative identities. The session began with a warm-up featuring reading comprehension, grammar practice and mediation tasks. Students then critically analyzed the trailer for the Dickinson series before creating their own English subtitles for a selected scene. The lesson concluded with a reflective writing task, drawing from biographical notes, poems, and the trailer to explore Dickinson’s work from a feminist perspective, with particular emphasis on the role of sexuality in her poetry.

- Week 4: The participants worked on a lesson plan centered on Jane Austen. The objectives were to enhance audiovisual mediation and reception, improve written production and strengthen specific grammatical structures such as inversions and modal verbs. Additionally, the lesson encouraged a deeper understanding of human relationships through a feminist and class-conscious perspective while exploring Austen’s work from a feminist approach. The session began with a warm-up that provided historical and biographical context, followed by multiple-choice questions on key facts and a grammar-focused task. During the critical viewing phase, students took notes while watching the Pride and Prejudice trailer and then reflected on the topic of marriage as a trade. For the subtitling task, they were asked to create subtitles from scratch for a well-known scene from the film adaptation. The lesson concluded with a consolidation activity, where students wrote an essay analyzing a quote from Pride and Prejudice in relation to the topic of marriage as a trade.

- Week 5: The participants engaged in a lesson plan focused on Virginia Woolf. The objectives were to develop audiovisual mediation and reception skills, enhance written production and reinforce grammatical aspects such as conditional inversions, question tags and the use of infinitives and gerunds. Additionally, the lesson encouraged reflection on the importance of mental health and explored Woolf’s work from a feminist perspective, with particular attention to mental health issues. The session began with a warm-up that included reading a passage from Mrs. Dalloway, followed by comprehension questions and grammar exercises contextualized within the text. In the critical viewing phase, students watched the trailer for The Hours, a film in which Virginia Woolf is portrayed, and were asked to write brief predictions about the film’s content, focusing on mental health. For the subtitling task, they created subtitles for a scene in which Woolf discusses her mental health with her husband. The lesson concluded with a consolidation task, in which students were asked to write an essay on the role of cinema in raising awareness of mental health.

- Week 6: An additional week was granted to allow participants who had not yet finished the lesson plans to complete them.

- Week 7: During the final week, they repeated the assessments from Week 1, which included the language skills test, administered in a paper-based format under controlled conditions, as well as completing the ERI scale.

- June: two months after the end of the experiment, students were provided with the same language skill test and the ERI scale in order to gather the data for the post-delayed test. From April to June, students had the same regular theory lessons together with practical sessions based on traditional textbook practices.

3. Results

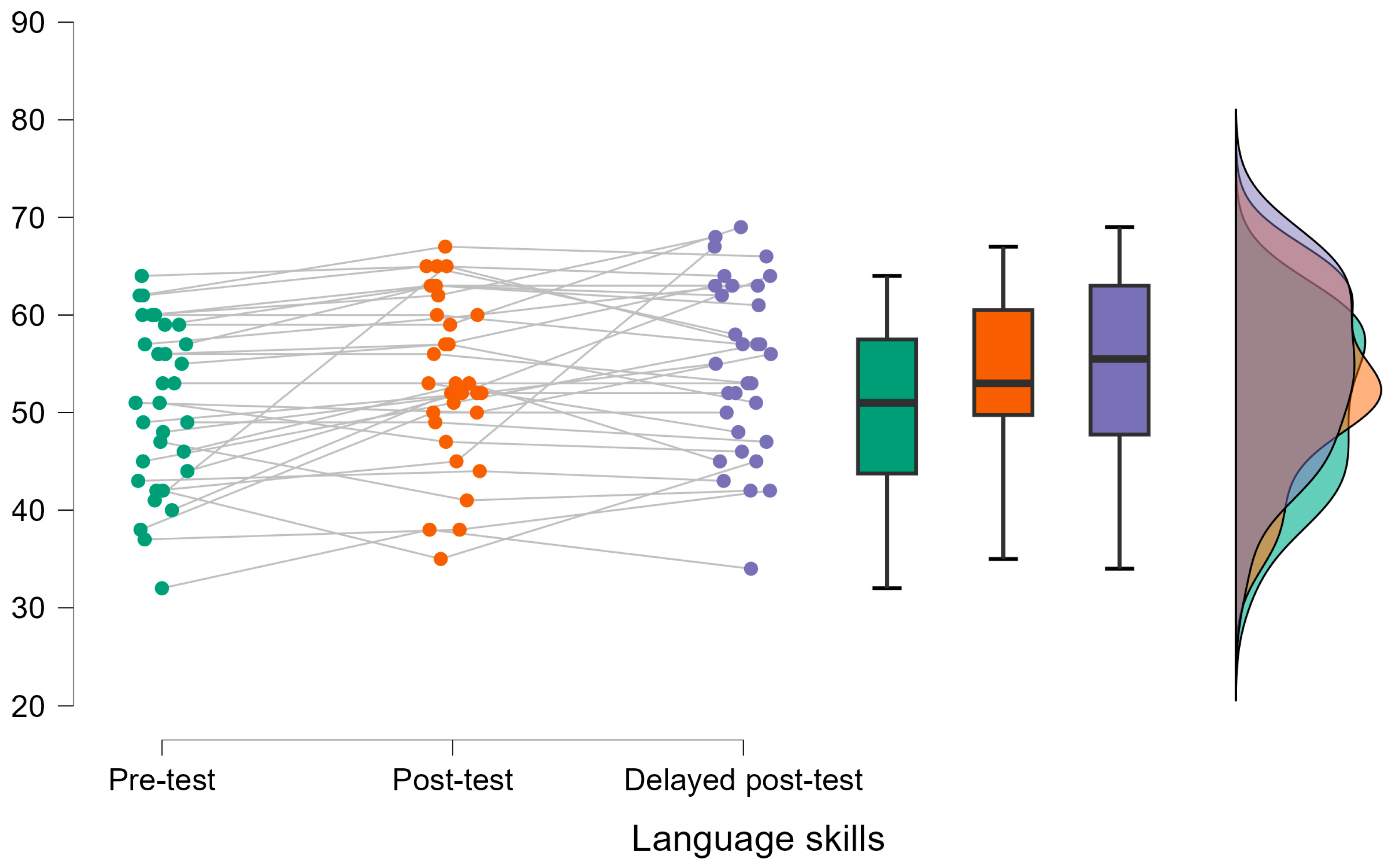

3.1. Language Gains

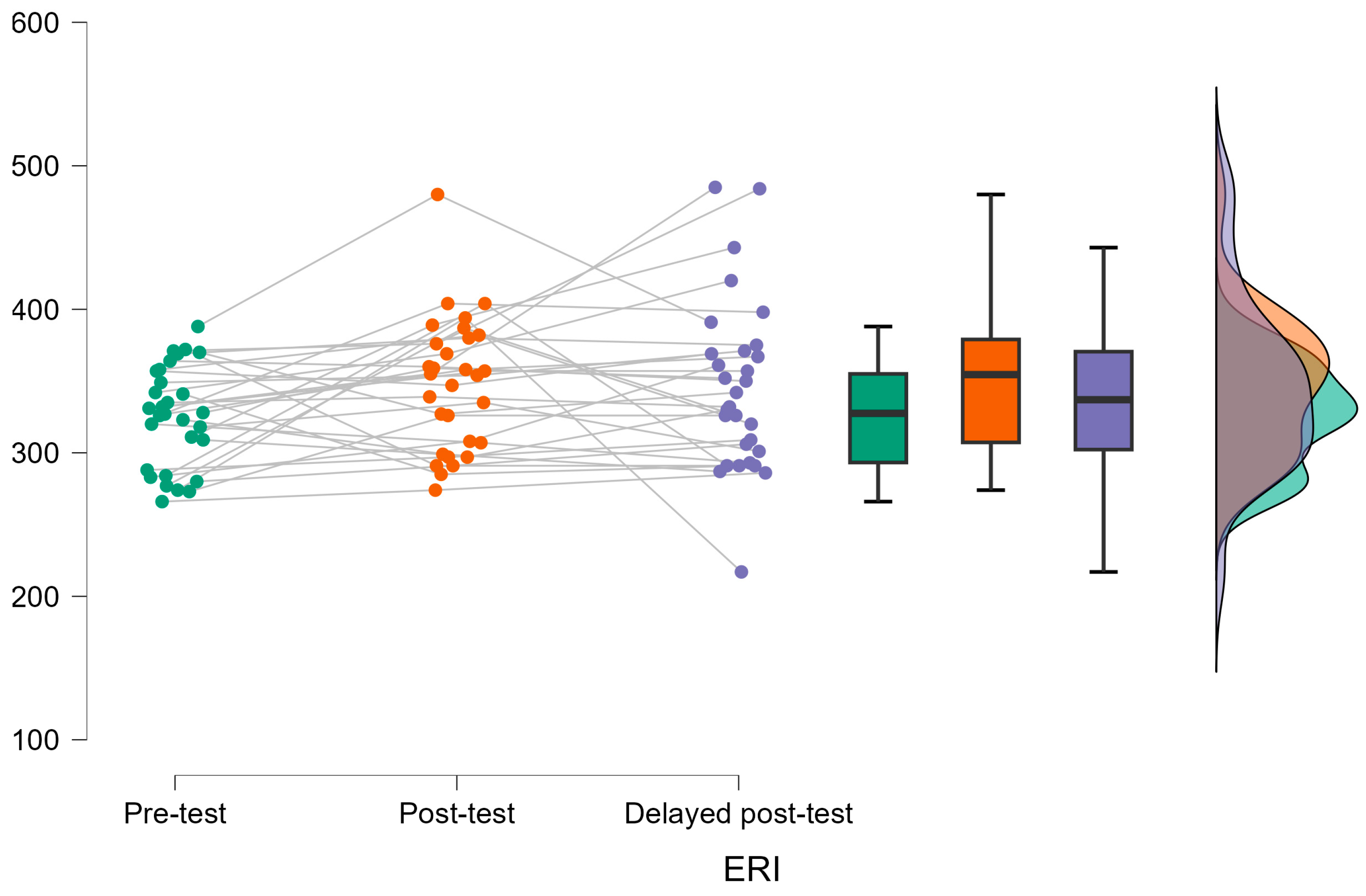

3.2. Interculturality

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Audio Description |

| AIALL | Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Language Learning |

| AVT | Audiovisual Translation |

| CALL | Computer-Assisted Language Learning |

| CLT | Cognitive Load Theory |

| DAT | Didactic Audiovisual Translation |

| DCT | Dual Coding Theory |

| LP(s) | Lesson Plan(s) |

| MALL | Mobile-Assisted Language Learning |

| PC | Personal Computer |

| PPP | Presentation, Practice, Production |

| SDH | Subtitling for the Deaf and hard of Hearing |

| TBL | Task-Based Learning |

| TS | Translation Studies |

References

- Abascal, E. G. F., Rodríguez, B. G., Sánchez, M. P. J., Díaz, M. D. M., & Sánchez, F. J. D. (2010). Psicología de la emoción. Editorial Universitaria Ramón Areces. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, H. M., Mahdi, H. S., & Alwathnani, D. (2023). Effectiveness of subtitles in L2 classrooms: A meta-analysis study. Education Sciences, 13(3), 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaiz-Castro, P., Gómez-Parra, M. E., & Espejo-Mohedano, R. (2022). An exploration of the impact of bilingualism on mobility, employability, and intercultural competence: The colombian case. Studia Anglica Posnaniensia, 57(1), 179–197. Available online: https://sciendo.com/article/10.2478/stap-2022-0008 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Ávila-Cabrera, J. J., & Corral Esteban, A. (2021). The project SubESPSKills: Subtitling tasks for students of business English to improve written production skills. English for Specific Purposes, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárcena, E. (2020). Hacia un nuevo paradigma de aprendizaje de segundas lenguas móvil, abierto y social. Propósitos y Representaciones, 8(1), e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, S. (2022). Subtitles as a tool to boost language learning and intercultural awareness? Journal of Audiovisual Translation, 5(1), 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños-García-Escribano, A. (2025). Practices, education and technology in audiovisual translation. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bolaños-García-Escribano, A., & Navarrete, M. (2022). An action-oriented approach to didactic dubbing in foreign language education: Students as producers. XLinguae, 5(2), 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillo de Larreta-Azelain, M. D., & Martín Monje, E. (2016). Students’ engagement in online language learning through short video lessons. Porta Linguarum, 26, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto-Cantero, P., Sabaté-Carrové, M., & Gómez-Pérez, M. C. (2021). Preliminary design of an initial test of integrated skills within TRADILEX: An ongoing project on the validity of audiovisual translation tools in teaching English. Research in Education and Learning Innovation Archives, 27, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danan, M. (2004). Captioning and subtitling: Undervalued language learning strategies. Meta, 49(1), 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J., & Skerrit, G. (2020). Macmillan english hub C1 (Iberia ed.). Macmillan Education. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Cintas, J. (1995). El subtitulado como técnica docente. Vida Hispánica, 12, 10–14. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10044/1/1400 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Díaz-Cintas, J. (1997). Un ejemplo de explotación de los medios audiovisuales en la didáctica de lenguas extranjeras. In M. Cuellar (Ed.), Las nuevas tecnologías integradas en la programación didáctica de lenguas extranjeras (pp. 181–191). Universitat de Valencia. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Cintas, J., & Remael, A. (2021). Subtitling. Concepts and practices. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Costales, A., Talaván, N., & Tinedo-Rodríguez, A. J. (2023). Didactic audiovisual translation in language teaching: Results from TRADILEX. [Traducción audiovisual didáctica en enseñanza de lenguas: Resultados del proyecto TRADILEX]. Comunicar, 77, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumuselu, A. D., De Maeyer, S., Donche, V., & del Mar Gutiérrez Colon Plana, M. (2015). Television series inside the EFL classroom: Bridging the gap between teaching and learning informal language through subtitles. Linguistics and Education, 32((Pt B)), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego Espinosa, V. M. (2018). “CALL” computer assisted language learning. Letras ConCiencia TecnoLógica, 4, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J. (2020). CALL research: Where are we now? ReCALL, 32(2), 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Plasencia, Y. (2020). Instrumentos de medición de la competencia comunicativa intercultural en español LE/L2. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 7(2), 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vera, P. (2021). Building bridges between audiovisual translation and english for specific purposes. Iberica, 2021(41), 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Parra, M. E. (2018). Bilingual and intercultural education (BIE): Meeting 21st century educational demands. Theoria et Historia Scientiarum, 15, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Parra, M. E., Huertas-Abril, C. A., & Espejo-Mohedano, R. (2021). Key factors to evaluate the impact of bilingual programs: Employability, mobility and intercultural awareness. Porta Linguarum, 2021(35), 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmer, J. (2015). The practice of english language teaching (5th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hestiana, M., & Anita, A. (2022). The role of movie subtitles to improve students’ vocabulary. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 3(1), 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Abril, C. A., & Gómez-Parra, M. E. (2018). Inglés para fines sociales y de cooperación: Guía para la elaboración de materiales. Graò. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas-Abril, C. A., & Palacios-Hidalgo, F. J. (2023). New possibilities of artificial intelligence-assisted language learning (AIALL): Comparing visions from the East and the West. Education Sciences, 13(12), 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. Pergamon. [Google Scholar]

- Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon. [Google Scholar]

- Krashen, S. (1989). We acquire vocabulary and spelling by reading: Additional evidence for the input hypothesis. The Modern Language Journal, 73(4), 440–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrea-Espinar, Á., & Raigón-Rodríguez, A. (2019a). Sitcoms as a tool for cultural learning in the EFL classroom. Pixel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educacion, 56, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrea-Espinar, Á., & Raigón-Rodríguez, A. (2019b). The development of culture in English foreign language textbooks: The case of English File. Revista de Lenguas Para Fines Específicos, 25(2), 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrea-Espinar, Á., & Raigón-Rodríguez, A. (2022). Unveiling American values using sitcoms. Porta Linguarum, 2022(37), 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertola, J. (2019). Audiovisual translation in the foreign language classroom: Applications in the teaching of English and other foreign languages. Research-Publishing.net. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sierra, J. J. (2018). PluriTAV: Audiovisual translation as a tool for the development of multilingual competencies in the classroom. In T. Read, S. Montaner-Villalba, & B. Sedano-Cuevas (Eds.), Technological innovation for specialized linguistic domains. Languages for digital lives and cultures. Proceedings of TISLID’18 (pp. 85–95). Éditions Universitaires Européennes. [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin, L. I., & Lertola, J. (2015). Captioning and revoicing of clips in foreign language learning-using Clipflair for teaching Italian in online learning environments. In C. Ramsey-Portolano (Ed.), The future of Italian teaching: Media, new technologies and multi-disciplinary perspectives (pp. 55–69). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Negi, S., & Mitra, R. (2022). Native language subtitling of educational videos: A multimodal analysis with eye tracking, EEG and self-reports. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(6), 1793–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogea-Pozo, M. d. M. (2018). Subtitulado del género documental: De la traducción audiovisual a la traducción especializada. Sindéresis. [Google Scholar]

- Ogea-Pozo, M. d. M. (2020a). La traducción audiovisual desde una dimensión interdisciplinar y didáctica. Sindéresis. [Google Scholar]

- Ogea-Pozo, M. d. M. (2020b). Subtitling documentaries: A learning tool for enhancing scientific translation skills. Current Trends in Translation Teaching and Learning E, 7, 445–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogea-Pozo, M. d. M., & Talaván, N. (2024). Teaching languages for social and cooperation purposes: Using didactic media accessibility in foreign language education. In A. B. García-Escribano, & M. Oakín (Eds.), Inclusion, diversity and innovation in translation education (pp. 69–91). UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paas, F., & Sweller, J. (2014). Implications of cognitive load theory for multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 27–42). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Lara, C., del Mar Ogea-Pozo, M., & Botella-Tejera, C. (2024). Empirical studies in didactic audiovisual translation. Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverter Oliver, B., Cerezo Merchán, B., & Pedregosa, I. (2021). PluriTAV didactic sequences: Concept, design and implementation. In J. J. Martínez-Sierra (Ed.), Multilingualism, translation and language teaching (pp. 57–76). Tirant Humanidades. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Arancón, P. (2023). Developing L2 intercultural competence in an online context through didactic audiovisual translation. Languages, 8(3), 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Arancón, P., Bobadilla-Pérez, M., & Fernández-Costales, A. (2024). Can didactic audiovisual translation enhance intercultural learning through CALL? Validity and reliability of a students’ questionnaire. Journal for Multicultural Education, 18(1–2), 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoli, S. (2006, May 1–5). Learning via subtitling (LvS). A tool for the creation of foreign language learning activities based on film subtitling. Marie Curie Euroconferences MuTra: Audiovisual Translation Scenarios (pp. 66–73), Copenhagen, Denmark. Available online: http://www.translationconcepts.org/pdf/MuTra_2006_Proceedings.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Sokoli, S. (2015). ClipFlair: Foreign language learning through interactive revoicing and captioning of clips. In Y. Gambier, A. Caimi, & C. Mariotti (Eds.), Subtitles and language learning (pp. 127–148). Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Soler Pardo, B. (2020). La subtitulación y el doblaje como recursos didácticos para aprender inglés como lengua extranjera utilizando el software Clipflair. Lenguaje y Textos, 51, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaván, N. (2006). Using the technique of subtitling to improve business communicative skills. Revista de Lenguas Para Fines Específicos, 12, 313–346. Available online: https://ojsspdc.ulpgc.es/ojs/index.php/LFE/article/view/170 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Talaván, N. (2010). Subtitling as a task and subtitles as support: Pedagogical applications. In J. D. Cintas, A. Matamala, & J. Neves (Eds.), New insights into audiovisual translation and media accessibility (pp. 285–299). Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaván, N. (2013). La subtitulación en el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras. Octaedro. [Google Scholar]

- Talaván, N., Ibáñez, A., & Bárcena, E. (2017). Exploring collaborative reverse subtitling for the enhancement of written production activities in English as a second language. ReCALL, 29(1), 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaván, N., & Lertola, J. (2022). Audiovisual translation as a didactic resource in foreign language education. A methodological proposal. Encuentro: Revista de Investigación e Innovación en la Clase de Idiomas, 30, 23–39. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10017/50584 (accessed on 26 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Talaván, N., Lertola, J., & Costal, T. (2016). iCap: Intralingual captioning for writing and vocabulary enhancement. Alicante Journal of English Studies, 29, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaván, N., Lertola, J., & Fernández-Costales, A. (2024). Didactic audiovisual translation and foreign language education. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaván, N., & Rodríguez-Arancón, P. (2024a). Didactic audiovisual translation in online context: A pilot study. Hikma: Estudios de Traducción, 23(1), 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaván, N., & Rodríguez-Arancón, P. (2024b). Subtitling short films to improve writing and translation skills. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada, 37(1), 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy-Ventura, N., Huensch, A., Katz, J., & Mitchell, R. (2024). Is second language attrition inevitable after instruction ends? An exploratory longitudinal study of advanced instructed second language users. Language Learning, 75(1), 42–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderplank, R. (1988). The value of teletext subtitles in language learning. ELT Journal, 42(4), 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderplank, R., & Feng Teng, M. (2024). Intentional vocabulary learning through captioned viewing: Comparing Vanderplank’s “cognitive-affective model” with Gesa and Miralpeix. In X. Feng, F. Teng, A. Kukulska-Hulme, & D. Wu (Eds.), Theory and practice in vocabulary research in digital environments (pp. 2–24). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Veroz-Gónzalez, M. A. (2024). Integrating didactic audiovisual translation for improved French language acquisition in translation and interpreting programmes. In C. Plaza-Lara, M. del Mar Ogea-Pozo, & C. Botella-Tejera (Eds.), Empirical studies in didactic audiovisual translation (pp. 47–66). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., & Lee, C. I. (2021). Multimedia gloss presentation: Learners’ preference and the effects on efl vocabulary learning and reading comprehension. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 602520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Lucas, M., Bem-Haja, P., & Pedro, L. (2023). Analysis of short videos on TikTok for learning Portuguese as a foreign language. Comunicar, 31(77), 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Language Skills | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | 32 | 50.563 | 8.496 |

| Post-test | 32 | 53.656 | 8.635 |

| Delayed post-test | 32 | 54.781 | 8.932 |

| Cases | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language gains | 305.438 | 2 | 152.719 | 7.148 | 0.002 | 0.187 |

| Residuals | 1324.562 | 62 | 21.634 | - | - | - |

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Mean Difference | SE | t | Cohen’s d | pbonf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | 3.094 | 1.001 | 3.090 | 0.356 | 0.013 |

| Delayed-post-test | 4.219 | 1.320 | 3.197 | 0.485 | 0.010 | |

| Post-test | Delayed-post-test | 1.125 | 1.123 | 1.002 | 0.129 | 0.973 |

| Intercultural Competence | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | 30 | 325.533 | 36.066 |

| Post-test | 30 | 347.700 | 45.845 |

| Delayed post-test | 30 | 345.700 | 59.699 |

| Cases | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercultural competence | 9020.556 | 2 | 4510.278 | 3.084 | 0.056 | 0.096 |

| Residuals | 84810.778 | 58 | 1462.255 |

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Mean Difference | SE | t | Cohen’s d | pbonf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | 22.167 | 8.841 | 2.507 | 0.462 | 0.054 |

| Delayed-post-test | 20.167 | 9.919 | 29 | 0.421 | 0.154 | |

| Post-test | Delayed-post-test | 2.000 | 10.765 | 0.186 | 0.042 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tinedo-Rodríguez, A.-J. Technology-Enhanced Language Learning: Subtitling as a Technique to Foster Proficiency and Intercultural Awareness. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 375. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030375

Tinedo-Rodríguez A-J. Technology-Enhanced Language Learning: Subtitling as a Technique to Foster Proficiency and Intercultural Awareness. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):375. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030375

Chicago/Turabian StyleTinedo-Rodríguez, Antonio-Jesús. 2025. "Technology-Enhanced Language Learning: Subtitling as a Technique to Foster Proficiency and Intercultural Awareness" Education Sciences 15, no. 3: 375. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030375

APA StyleTinedo-Rodríguez, A.-J. (2025). Technology-Enhanced Language Learning: Subtitling as a Technique to Foster Proficiency and Intercultural Awareness. Education Sciences, 15(3), 375. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030375