1. Introduction

Civic engagement through participation is the focus of (modern) democracy, including in the school-age population and curricular and extracurricular activities of schools that enhance the civic engagement of their students. Civic engagement is instrumental to democracy, and its forms should be adapted to changes in society (

Checkoway & Aldana, 2013). While civic engagement is crucial for a thriving democracy, the ways in which citizens participate can vary. In representative democracies, individuals engage indirectly by electing officials to make decisions on their behalf. In contrast, participatory models of democracy emphasize direct citizen involvement in decision-making. Sieriakova and Kokoza’s qualitative study on civic education (although among university students) illustrates that students associate civic engagement with various forms of voluntary assistance and participation in political life and indicate engagement as value, reflecting a broader action-based approach to civic engagement (

Sieriakova & Kokoza, 2019). This suggests that civic (and citizenship) education can foster a sense of responsibility and community involvement, regardless of whether the democracy is representative or participatory. This perspective also aligns with the understanding that while civic engagement is crucial, the methods and structures through which it is realized can vary significantly. Therefore, civic and citizenship education today carries high expectations, as it plays a pivotal role in preparing individuals for active participation in democratic processes, whether it is formalized as a separate subject, integrated across subjects, or implemented through the overall functioning of the school. This educational framework fosters civic engagement, upholds democratic values, and equips students for informed participation—regardless of the formal status of a particular subject or a whole-school approach. A key goal of civic and citizenship education is to equip young people with the knowledge and skills needed to engage with civic institutions and issues, enabling them to participate actively as responsible citizens in adulthood (

Schulz et al., 2025). Research emphasizes that civic and citizenship education is essential to a functioning democracy as it has a critical role in fostering informed, responsible, and engaged individuals and communities capable of addressing contemporary societal challenges. For example, longitudinal study results show that engagement during adolescence predicts citizenship engagement in adulthood, 10 to 15 years later (

Obradović & Masten, 2007), including adolescent minorities (

Chan et al., 2014). From the perspective of the school environment, one of the key findings in the literature is that a supportive school environment enhances civic engagement among students.

Lenzi et al. (

2014) emphasize that a democratic school climate, characterized by open discussions about civic issues and opportunities for student participation, positively correlates with students’ sense of civic responsibility and their intentions to engage in civic activities later in life. Another study demonstrated the role of an open classroom climate in fostering students’ civic knowledge and efficacy (

Knowles & McCafferty-Wright, 2015). Additionally, the research found that adolescents’ civic knowledge and attitudes significantly “influence” their future likelihood of voting, indicating that school-based interventions can effectively enhance civic engagement (

Cohen & Chaffee, 2012). However, another longitudinal research also shows that from a practical standpoint, it is important to recognize that highly engaged youth do not automatically remain civically active; ongoing civic discussions—particularly those with parents and friends—along with other opportunities, are essential for sustaining long-term engagement (

Wray-Lake & Shubert, 2019).

Hoskins et al. (

2011) highlight the significant impact of civic and citizenship education on students’ civic knowledge and attitudes, which are essential for fostering belonging and responsibility in democratic societies. But it seems that this is similar for both Western and Eastern political contexts, as, similarly,

Geske and Čekse (

2013) emphasize that civic and citizenship education should cultivate both knowledge and a commitment to civic engagement. The systematic literature review of 25 controlled trials on civic and citizenship education and political engagement confirms the value of participatory methods, whole-school approaches, and teacher training while highlighting the lack of strong causal evidence and funding challenges in the field (

Donbavand & Hoskins, 2021). In summary, civic and citizenship education is vital for preparing students for active participation in democracy, equipping them with the knowledge and skills necessary for responsible engagement, regardless of the political context or (specific) educational approach. Although many different contexts (such as individual or familial) are important for this, the school context still remains important.

When discussing civic and citizenship education in schools today, it is important to emphasize that a minimalistic approach—focused on providing basic information about the constitution, political system, and laws and fostering only essential civic virtues like obeying laws, solidarity, and voting—has long been insufficient (

Klemenčič, 2012). Instead, a maximalist approach is highlighted, emphasizing broad definitions of citizenship; fostering critical and independent thinking; reflecting on societal values, justice, and democracy; and developing public virtues such as engagement in solving societal and global issues. The primary goal of this approach is not just to inform but to equip students to apply this knowledge, enhancing their understanding and capacity for active participation/engagement (

Klemenčič, 2012). However, this distinction is not something new; it was already discussed by

McLaughlin (

1992) in terms of the complex and contested term of citizenship that also concerns “education for citizenship”. McLaughlin discusses not two distinct conceptions but rather two contrasting or continuum-based interpretations of “education for citizenship”—minimal and maximal—illustrated through four key aspects: identity, necessary virtues, the expected level of political involvement of the individual they thought to follow, and the social prerequisites for effective citizenship. He also emphasizes that the key difference between minimal and maximal interpretations of “citizenship education” lies in the emphasis on students’ critical understanding and thinking and the depth of liberal and political education involved (

McLaughlin, 1992). To some extent, this “distinction” is also reflected in the understanding of civic education (or civics) and citizenship education. “Citizenship education” and “civic education or civics” are largely interchangeable terms, though “civics” is often linked to more traditional approaches that emphasize knowledge of the constitution and political institutions (

McCowan & Gomez, 2012). However, recognizing this complexity, many civic education programs in Western democracies over the past two (or three) decades have aimed not only to impart knowledge of political systems and rights but also to promote active, participatory citizenship aligned with McLaughlin’s maximal interpretation (

Peterson & Bentley, 2016). These initiatives combine civics education with service learning, emphasizing that citizenship is not just about understanding but also about responsible action within a community (

Boyte, 2003;

Peterson & Bentley, 2016). Focus on this approach is also visible in European countries (

Eurydice, 2017) and/or countries participating in the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (

Schulz et al., 2025) when examining the main goals of civic and citizenship approaches in these countries/educational systems.

As society changes, new or, to some extent, renewed approaches to civic engagement are needed to build future capacity; however, this does not mean that some traditional approaches will and should disappear. While traditional citizen participation once sufficed, there is now a demand for innovative forms of engagement and fresh perspectives (

Checkoway & Aldana, 2013) but also on already established forms. They identified the following basic strategies: preparing young people for civic involvement in a diverse democracy involves encouraging participation in established institutions that support existing power structures (for example, participation through formal political and governmental institutions), teaching grassroots organizing to challenge power (forming a group for social and political action), fostering intergroup dialogue for inclusive communication (encourage meaningful dialogue that facilitates communication, enhances the understanding, examines issues and drives change, and promotes sociopolitical development to raise awareness), and empowering individuals and redistributing power in society (which fosters critical awareness of societal participation, particularly the individual and structural factors that influence engagement). Based on the same authors, each form of civic engagement has a unique educational approach (such as citizen participation—civics/citizenship courses, student government, and school clubs; grassroots organizing—community workshops, afterschool programs, and summer internships; intergroup dialogue—school courses, afterschool dialogues, weekend retreats, and summer programs; and sociopolitical development—social justice and human rights groups, schools, community organizations, and university-community partnerships). They continue, adding that some advocate for a “new civics” that merges these into one unified model, and this often comes from educational elites who do not represent marginalized groups in society (

Checkoway & Aldana, 2013). Innovative forms of adolescent and youth engagement in society have evolved significantly, particularly in response to changing social dynamics (such as closures of in-person spaces) and the increasing role of technology. Digital activism has emerged as a vital platform for youth engagement. Interviews with high school and college students reveal that digital and social media play a crucial role in adolescent activism by supporting traditional political engagement, with significant overlap between their online and offline networks (

Maher & Earl, 2019).

Wilf et al. (

2023) discuss how online spaces have become central for youth civic actions, especially during significant social movements like Black Lives Matter and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors argue that social media not only facilitates communication but also empowers adolescents and youth, in general, to participate in critical civic discussions and actions, thereby expanding the traditional boundaries of civic engagement.

Some studies on adolescent civic engagement focus on the cognitive aspects of civics and citizenship, but it is equally important to consider how their emotional and behavioral responses to political and social issues shape their future civic engagement (

Alva et al., 2023). While lower-secondary students (which are the target students of this article) are not yet fully able to participate in society (in terms of electoral participation, as they do not have voting rights yet), they are still expected to participate in other forms (both in school and beyond), and the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) emphasizes measuring their (behavioral) intentions for future engagement (

Schulz, 2024). This aligns with the theory of planned behavior (

Schulz, 2024), which links attitudes to behavior through intentions. The theory of planned behavior (

Ajzen & Fishbein, 2000) suggests that human actions are driven by three factors: behavioral beliefs (about consequences), normative beliefs (about others’ expectations), and control beliefs (about factors that help or hinder action). These beliefs shape attitudes, perceived social pressure (subjective norms), and perceived behavioral control. Together, these elements form behavioral intentions, which predict actions. Stronger intentions arise from positive attitudes, supportive norms, and higher perceived control. While intention directly precedes behavior, perceived control also influences action, especially when execution is challenging, making it a useful predictor alongside intention (

Ajzen & Fishbein, 2000). Additionally, school-based engagement offers young people experiences with political activities that positively influence future participation (

Keating & Janmaat, 2016; in

Schulz, 2024), as already discussed above.

Expected future civic engagement can refer to various types of activity extending beyond politics to broader aspects of community life, including promoting and supporting actions in support of social issues (

Verba et al., 1995). Around half a century ago, scholars introduced the concept of unconventional activities associated with social movements, such as grassroots campaigns and protests (

Barnes & Kaase, 1979; in

Schulz, 2024). These unconventional forms of engagement may involve both legal and illegal efforts aimed at promoting social reform and action (

Kaase, 1990), distinguishing them from conventional activities like political party engagement, voting, or running for office (

Alscher et al., 2022;

Schulz, 2024). Although called unconventional at that time, today, we cannot characterize them as unconventional anymore. We could also call them normative and non-normative collective actions. Normative collective actions, such as legal demonstrations and public protests, align with societal norms, while non-normative actions challenge the legitimacy of the social system through illegal or socially unacceptable activities (

Gil De Zúñiga & Goyanes, 2023;

Wright, 2010;

Wright et al., 1990). Unconventional or non-normative forms can encompass a spectrum of activities, from moderate and non-violent actions (such as participating in marches and signing petitions) to more radical or violent forms (including the destruction of public or private property) (

Zúñiga et al., 2023). To influence political agendas or outcomes, citizens may engage in extra-parliamentary activities/manifestations, often called protest behavior. However,

Ekman and Amnå (

2012) avoid the term “unconventional”, as actions like signing petitions or joining demonstrations are now common. Instead, they refer to extra-parliamentary participation, distinguishing between its legal and illegal forms. Legal extra-parliamentary activities include participating in demonstrations, strikes, and protests, as well as engaging in groups or parties that operate outside the parliamentary sphere, such as social movements or political action groups. These forms of participation/engagement, like involvement in women’s rights, animal protection, or global justice movements, particularly appeal to young people. Unlike traditional political parties, they are non-hierarchical and offer more than just advocacy—they provide a sense of action, personal engagement, and the opportunity to make a difference (

Ekman & Amnå, 2012).

The motivation to participate in (political) protests is assumed to be related to a wish for their voices to be heard and to influence public opinion in order to invoke actions from the governments. Protests are an indicator of democracy where citizens are entitled to participate in peaceful protests that represent the collective basic level action for achieving social change for the disadvantaged ones. On the other hand, illegal protests are an effective form of civil disobedience (

Kuang & Kennedy, 2020). Previous studies on adolescents (e.g.,

Ainley & Schulz, 2011) have found that the expected participation in illegal protests is related to multiple factors like civic knowledge, citizenship self-efficacy, community participation experiences, interest in social and political issues, and internal political efficacy. Self-efficacy is also related positively to expected participation in illegal protests. Expected illegal protests, however, are also related negatively to the trust in governmental institutions (

Ainley & Schulz, 2011). In addition, negative civic participation (including illegal protests in the future) is related to negative traditional values, previous participation experiences, civic values, poor attitudes toward democratic values, as well as toward issues of social equality (

Kuang & Kennedy, 2020).

While illegal protests can be viewed with skepticism, numerous scholars argue that they can be legitimate forms of civic engagement, particularly when they arise in response to systemic injustices or oppressive political conditions.

Dahl and Stattin (

2015) assert that illegal political activities, including protests, can be justified as a symbolic rejection of an oppressive system. They argue that when legal avenues for change are blocked or ineffective, individuals may resort to illegal protests as a means of expressing dissent and demanding accountability from authorities. The results of their study among adolescents in Sweden show that adolescents engaged in illegal political activism appear to have similar resources for political participation as their legally engaged peers. However, they are more inclined to justify actions based on outcomes, likely reflecting a broader challenge to authority. Similarly,

Inguanzo et al. (

2021) explore the motivations behind unlawful political protests, suggesting that individuals may engage in these actions as a response to authoritarianism or perceived injustices within democratic systems. Also, their findings indicate that illegal protests can emerge as a form of resistance against oppressive political environments, thereby legitimizing such actions in the eyes of participants and sympathizers and that the illegal protesters are not substantially more ideologically extreme than the general population and that use of social media are strong predictors for illegal protest as well as prior protest activities are (nearly 95% of those in their sample who participated in illegal protests also took part in legal ones; a representative sample of the US population was achieved). Similarly,

Ekman and Amnå (

2012) have also pointed out that people who participate in illegal protests are also likely to take part in legal protests but not necessarily in traditional party activities. Protest-oriented or “new” political participation includes demonstrations, extra-parliamentary protests, signing petitions, and political consumption (e.g., boycotts), so they go beyond “actual” political participation (

Ekman & Amnå, 2012).

There is a visible trend in the increasing number of protests all over the world.

Ortiz et al. (

2022) investigated the trends in protest on a world scale between 2006 and 2020. They found that in Europe and Central Asia, for example, the number of protests increased from 119 in 2006–2010 to 368 in 2016–2020, i.e., more than three times. A similar picture was seen in North America, 44 vs. 126 protests. Protests increased significantly in middle-income and high-income countries. Global and international protests also show rising numbers, with a total of 239 protests between 2006 and 2020. The largest number of protests (1503) was due to the failure of political representation and political systems, followed by economic justice and anti-austerity protests (1484), civil rights protests (1360), and global justice protests (897). Many of the protests took action that was beyond the legal allowance. In many cases, the protests turned into crowd violence. About 20% of the protests between 2006 and 2020 ended in vandalism, looting, and violence. Some examples of such protests, amongst many others, are the radical right protests for the return of the monarchy and against LGBT rights in Brazil, protests against COVID-19 lockdowns and a lack of jobs in Chile and Senegal, and the “yellow vests” in France and Ireland (

Ortiz et al., 2022).

The purpose of this article is to investigate the 14-year trends in expected participation in illegal protests using the data from three cycles of the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) (i.e., 2009, 2016, and 2022) conducted by the IEA (

IEA & ACER, 2024). ICCS is a cross-sectional study providing trend items on various civic and citizenship topics in education, including expectations for participation in illegal protest activities. In the study, 8th-grade students (except for Norway, where 9th-grade students were used) participated. Previous studies (e.g.,

Ainley & Schulz, 2011) on “old” data have found several associations between participation in protests and students’ civic knowledge and other individual characteristics, and now we are testing this with newer data and from the trend perspective. In addition, this study also explores the changes in the association between self-reported future participation in illegal protests and the measures available in ICCS databases. The purpose of this article is, therefore, to investigate the trends of students in grade 8 (in Denmark, Malta, Slovenia, Italy, Estonia, Colombia, Sweden, Netherlands, Chinese Taipei, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Latvia) and grade 9 (Norway) in terms of their expectations of participating in illegal protest activities in countries participating in all three cycles of the ICCS (2009, 2016 and 2022)—overall, by gender and by immigration background.

From this perspective, three research questions arise:

What individual factors are associated with 8th-grade students toward intended illegal protest activities in the future for students from twelve European countries?

How is the civic knowledge of students associated with intended illegal protest activities in the future?

How is the attitudinal context of students (their self-efficacy perception, interest in political and social issues, and trust in civic institutions) associated with their future intentions for illegal protests over time?

This article offers significant insights for educational sciences by examining the factors associated with adolescents’ inclinations toward illegal protest activities. Implications for educational sciences and school practices can be manifold, such as (1) curriculum development, integrating robust civic and citizenship education programs that enhance students’ understanding of legal avenues for political participation that can reduce the allure of illegal activities, and (2) addressing students’ individual factors: educational interventions should consider the individual factors of students, such as gender differences and immigration backgrounds, providing additional support and resources to those from disadvantaged backgrounds to prevent marginalization that could lead to illegal protest intentions. Our article is the first glance at this topic and investigates the association between intended illegal protest activities, civic knowledge, and some individual students’ backgrounds (such as immigration status and gender differences) and attitudinal contexts, e.g., self-efficacy perception, interest in political and social issues, and trust in civic institutions.

3. Results

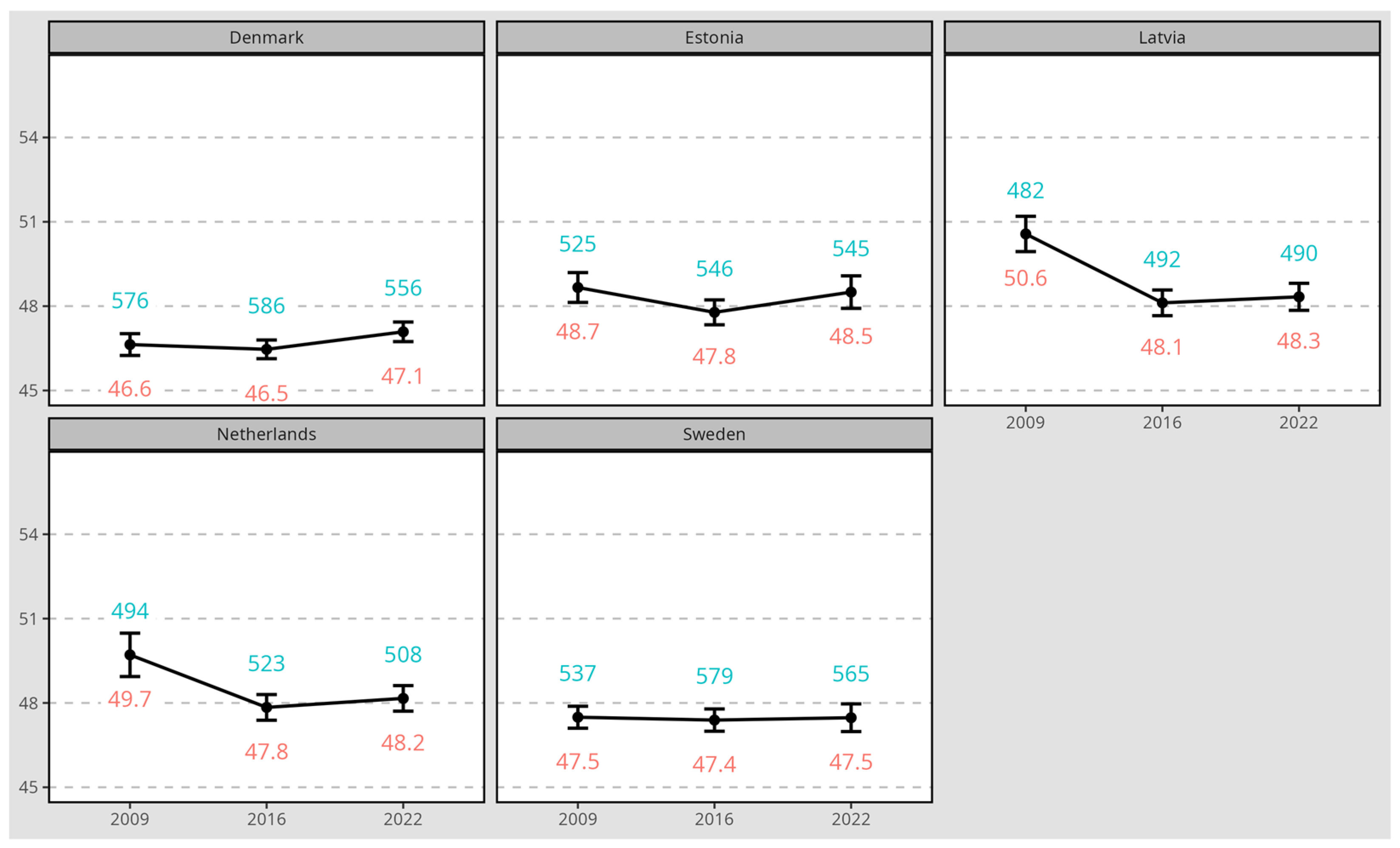

For clarity and ease of comprehension, the results of the trends in average students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities are presented graphically. The countries’ overall trends are presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Exact statistical tests are provided in the tables in

Appendix A. The numbers in red in the figures are the estimates of average scale scores of the students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities scale, and the numbers in blue represent the average civic knowledge scores in each ICCS cycle. Each of these figures contains a graphical representation of a different set of countries depending on the trends in students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities.

Figure 1 presents the countries with low (and even negative) changes,

Figure 2 with medium changes, and

Figure 3 with large changes in students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities over the cycles of ICCS. In these figures, the numbers in blue represent the average civic achievement scores, the numbers in orange represent the average on the intended future illegal protest participation scale. In Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, the Netherlands, and Sweden, the changes are very small. In Latvia, the overall changes across the cycles are even negative. In Denmark, the average is insignificantly higher in 2016 compared to 2009, and in 2022, it increases significantly, but it is just 0.63 points. In Estonia, the average first decreases significantly from 2009 and then increases significantly from 2016 to 2022, reaching approximately the same level as 2009 (no significant difference between 2009 and 2022). In Latvia, the level drops significantly from 2009 to 2016 by 2.5 points and remains about the same in 2022 (insignificant difference between 2016 and 2022). The trends in the Netherlands are the same as those in Latvia. In Sweden, the levels of expected student participation in illegal protest activities change only by up to 0.10 points across the three cycles, and none of the changes is significant.

Figure 2 presents the trends in countries with medium changes in students’ expected participation in illegal activities (Bulgaria, Chinese Taipei, Lithuania, and Norway). In Bulgaria, the levels of expected participation in illegal protest activities increase steadily, with differences being significant between 2009 and 2016 and 2009 and 2022. This trend is very similar in Chinese Taipei, although the overall results in the three cycles are much lower. In Norway, the difference between 2009 and 2016 is statistically insignificant but is larger and statistically significant between 2009 and 2022 and between 2016 and 2022. In Lithuania, the trend is first downward from 2009 to 2016, although very small (0.14 points) and insignificant, but the difference between 2016 and 2022 is larger and significant.

Figure 3 presents the results with the largest changes in students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities. In Malta, the average increases between 2009 and 2016 by 2.75 points, and the difference is statistically significant. In 2022, the average decreases and is significantly lower than in 2016 but still significantly higher than in 2009. In Slovenia, the average increases between 2009 and 2016 but is small (0.35 points) and insignificant. However, the difference between 2016 and 2022 becomes much bigger (2.37 points) and is statistically significant. In Italy, the differences are significant between all three cycles and are increasing over time, from 0.74 (2009 to 2016) to 1.65 (2016 to 2022). The largest increasing trends are observed in Colombia, with all differences being statistically significant. There, the change between 2009 and 2016 is 3.65 points.

In general, the average overall trend in students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities increases over the ICCS cycles as civic knowledge decreases. This is mostly evident in Bulgaria, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Netherlands. In other countries, the pattern is unclear. For example, in Denmark, the levels in 2009 and 2016 are the same, but in 2016, the achievement is higher, while in 2022, the achievement is lower, and the expected participation in illegal protest is significantly higher. In Estonia, the average achievement in 2016 and 2022 is the same (just a one-point difference), with a significant increase in the average intentions to participate in illegal activities. However, there is a very small and insignificant difference in anticipated participation in illegal protest activities between 2009 and 2022, but the average achievement in civic knowledge is 20 points. In Sweden, the levels of anticipated participation in illegal protest activities are the same across all three cycles, but the achievement in civic knowledge varies by 42 points across all three years of the ICCS’s administration. Bulgaria is another interesting example, as the average civic knowledge scores increased along with the levels of students’ expectations to participate in illegal protest activities between 2009 and 2016; then, in 2022, the achievement scores in civic knowledge suddenly dropped by 29 points with the highest levels of expected participation in illegal protest activities across all cycles. In Norway and Slovenia, the average civic scores increase with the increase in students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities from 2009 to 2016; then, they suddenly drop with the highest levels of expected participation in 2022. The most interesting case is probably Chinese Taipei, where the increase in students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities increases steadily across the cycles, and so do the average scores in civic knowledge.

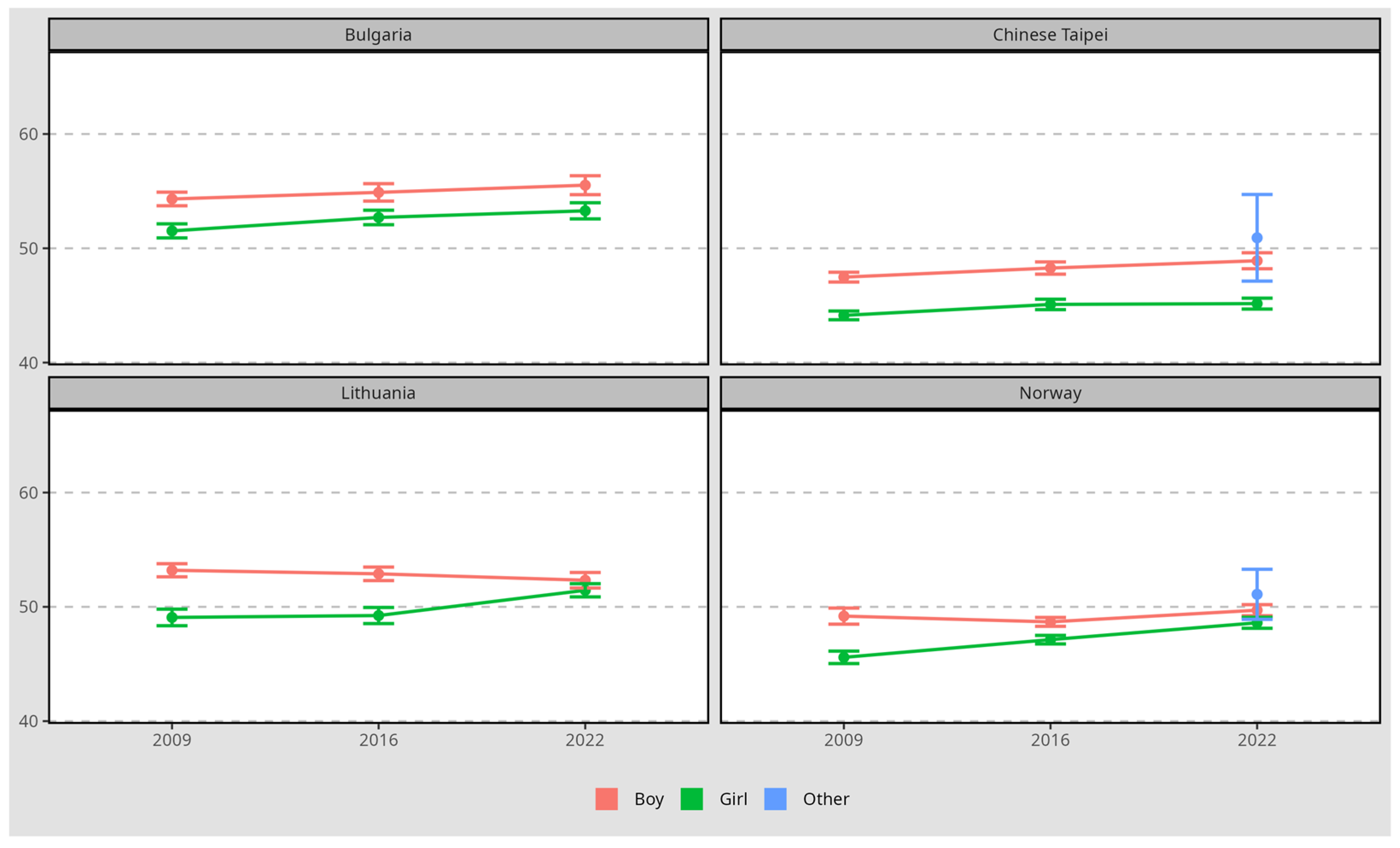

The presentation of the results continues with the findings on students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities by their gender (see

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 and

Table A2 and

Table A3 in

Appendix A for exact statistical tests). The countries are grouped as per the overall amount of changes across the cycles from above. Different patterns have been identified across the countries. First, in some countries (Denmark, Bulgaria, Chinese Taipei, Italy, and Slovenia), the levels of anticipated participation in illegal protest activities between boys and girls differ (boys had significantly higher expectations), and the trend lines are almost strictly parallel. Both female and male students in these countries show an increase in their expected participation in illegal protest activities. The differences are significant both across the cycles and between the two genders.

The other countries show different patterns. In Estonia, Latvia, and Sweden, male students have decreasing trends in their expectations, while female students show an increase in their expectations. In Lithuania and Norway, the trends are rather similar: male students have a steady but rather flat trend over time, while the expectations of female students to participate in illegal protest activities have increased. The common aspect in this group of countries is that the expectations of male students decrease or remain unchanged over time, while the expectations of female students increase steadily from 2009 to 2022, and while these gender differences are significant in all cycles, they decrease over time from 10.59 points in Norway and nearly 9 points in Lithuania to 1.10 points in Norway and 2.27 in Lithuania.

In Colombia, the trends for both genders increased steadily over time, but the increase from 2009 to 2022 for female students is much more rapid than for male students, and while the differences between males and females were significantly different in 2009 and 2016, in 2022, the difference was insignificant and very small, just 0.14 points on the scale (i.e., the gaps disappear). The trends in Malta are different from all other countries. The differences increased for both genders between 2009 and 2016, with more rapid growth for female students, and in both cycles, these differences are significant. In 2022, however, the average expectations for participating in illegal protest activities decreased significantly for male students while remaining the same for female students. While the gender differences in 2009 and 2016 in Malta are statistically significant, in 2022, they become statistically insignificant (i.e., there is no gap).

In addition, Chinese Taipei, Colombia, Denmark, Latvia, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden included the category “Other” for student gender in the questionnaire. Although in some countries, the results appear to be significantly different from those of male and female students (see the blue error bars in the figures below), there are too few cases (just one percent across the countries) to reliably estimate the levels for students with “Other” gender. Besides this, this category is present only in ICCS 2022. This is why no statistical tests were performed for these students, and the presentation of these results is omitted.

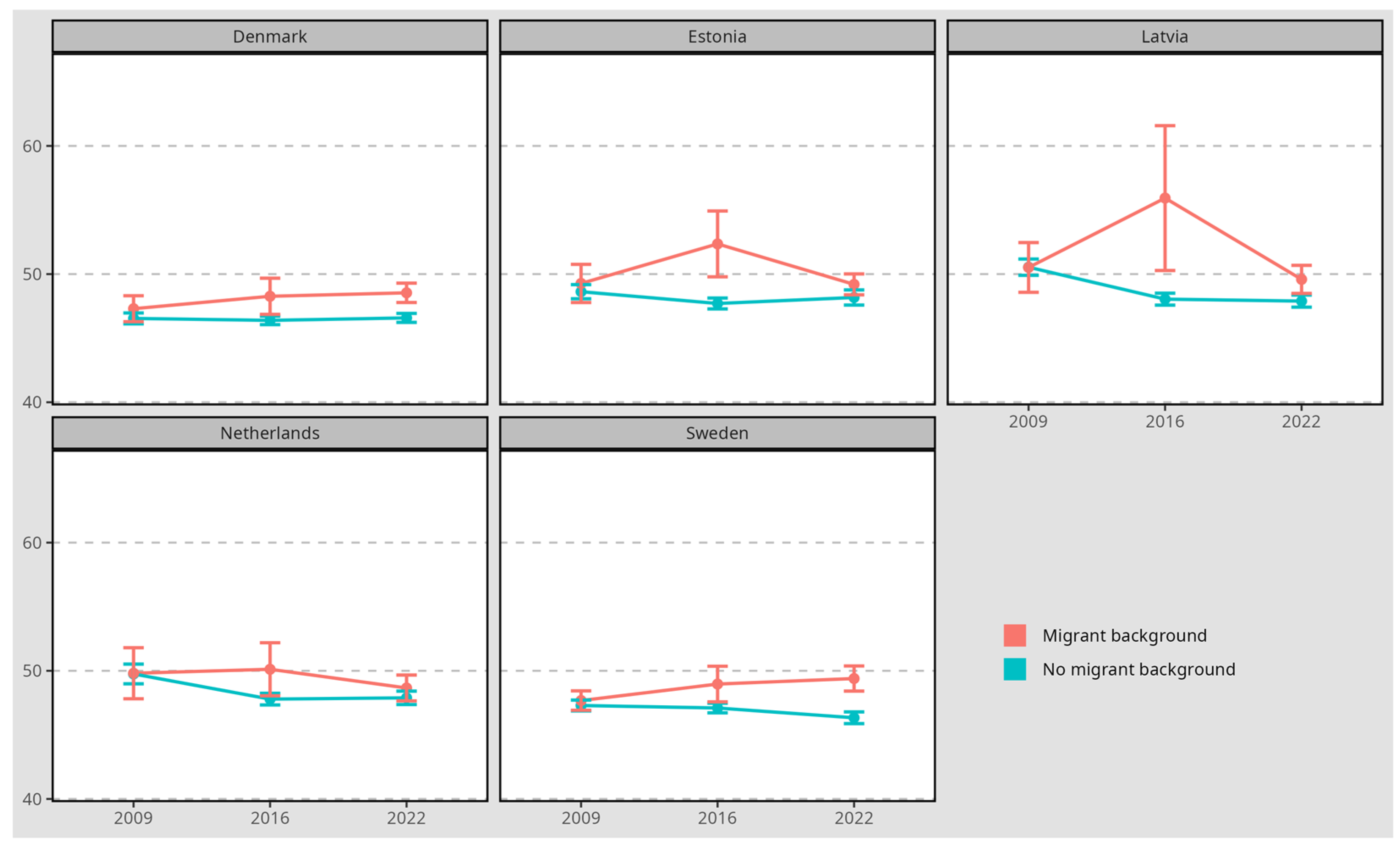

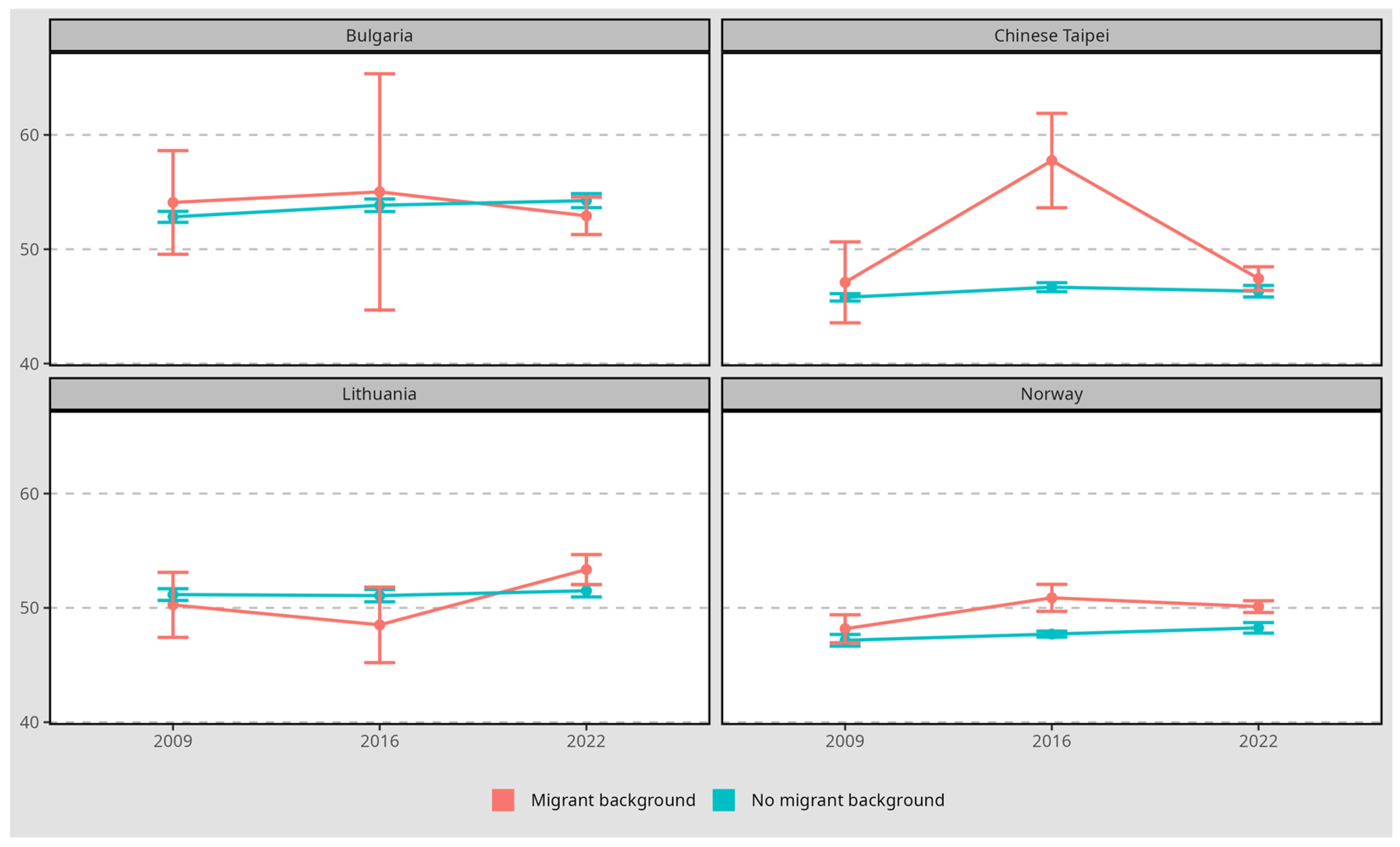

The last results in this article are on the trends in students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities by their immigration backgrounds (see

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 and

Table A4 and

Table A5 in

Appendix A). In general, students with immigrant backgrounds have higher expectations for taking part in illegal protest activities in all cycles of ICCS. In Colombia, Italy, and Slovenia, the trends of students with and without immigrant backgrounds participating are steadily increasing. In Colombia, however, the differences between students with and without an immigrant background are not significant in all three ICCS cycles, while in Italy, they are insignificant only in ICCS 2009. In Slovenia, the differences are significant in all three cycles. In Denmark, the trend for students without immigrant backgrounds remains stable over time, while for students with immigrant backgrounds, it is increasing (while small and insignificant in 2009, the differences increase and become significant in subsequent ICCS cycles). In Norway, the trend is quite similar to the one in Denmark, but with a slight decrease for students with an immigrant background in 2022. In Sweden, the trends are also similar, but with a significant, although small, decrease for students without an immigrant background from 2016 to 2022.

In Chinese Taipei, Estonia, Latvia, and Norway, the trends for students without an immigrant background remain steady or with a slight decrease, while the trends for students suddenly peaked in 2016 and then decreased again to the levels, or close to the levels, of 2009. These peaks for students with an immigrant background in 2009 are most prominent in Chinese Taipei and Latvia, are to a much lesser extent in Estonia, and are the least prominent in Norway.

In Malta, students with an immigrant background exhibit a downward trend in their expectations to participate in illegal protest activities, although, in all three cycles, their expectations are significantly higher than for students with no immigrant background. The trends for Maltese students with no immigrant background peaked in 2016, and then the expectations decreased again in 2022. However, the expectations of students with no immigrant background in 2022 are still significantly higher than in 2009.

In Bulgaria, students with an immigrant background had higher expectations than non-immigrant students in 2009 and 2016 and then lower in 2022, but none of the differences between students with and without an immigrant background are statistically significant across the three ICCS cycles. In Lithuania, exactly the opposite trends are observed, although the difference between students with and without an immigrant background is statistically significant (students with immigrant backgrounds are higher). In the Netherlands, the trends for both students with and without an immigrant background are monotonically decreasing, with a statistically significant difference in 2016 only (students with an immigrant background are higher).

The last analysis in this study is on the changes in the strength of association between students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities scale on the one hand and the students’ citizenship self-efficacy, students’ interest in political and social issues, and students’ trust in civic institution scales on the other hand. The results are presented in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4. The sorting of the tables is according to the relative changes in the strength of the associations of students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities with the rest of the scales.

Table 2 presents the changes in the association between students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities and students’ citizenship self-efficacy scales. All correlation coefficients are positive in all three cycles (i.e., positive changes in expected participation in illegal protest activities are also associated with positive changes in citizenship self-efficacy) in all cycles for all countries. The only exceptions are Denmark and Sweden in 2009, but their coefficients are very close to zero (

r = −0.01) and statistically insignificant. Over time, the strength of associations is changing. The associations were fairly low in 2009, whereas in four (Estonia, Denmark, Sweden, and Slovenia) out of the thirteen countries, the coefficients were insignificant. In 2016, the coefficient was insignificant only in Denmark. In 2022, the coefficients in all countries were significant. The smallest changes between 2009 and 2022 are observed in Italy (from

r = 0.09 to

r = 0.14), Estonia (from

r = 0.04 to

r = 0.11), Chinese Taipei (from

r = 0.16 to

r = 0.24), and Denmark (from

r = −0.01 to

r = 0.09). Medium changes in association between 2009 and 2022 are observed in the Netherlands (from

r = 0.11 to

r = 0.23), Malta (from

r = 0.17 to

r = 0.29), Lithuania (from

r = 0.10 to

r = 0.22), Latvia (from

r = 0.11 to

r = 0.25), and Bulgaria (from

r = 0.14 to

r = 0.29). The largest changes between 2009 and 2022 are observed in Norway (from

r = 0.07 to

r = 0.25), Colombia (from

r = 0.11 to

r = 0.30), Sweden (from

r = −0.01 to

r = 0.19), and Slovenia (from

r = 0.04 to

r = 0.25).

Table 3 presents the changes in the strength of association between students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities and students’ interest in political and social issues scales. In most countries, the correlations in all three cycles are negative (i.e., positive changes in student expected association with illegal protest activities are associated with negative changes in student interest, or vice versa). The strength of the association with a negative sign changes between 2009 and 2022 in Denmark (from

r = −0.05 to

r = −0.09). In Malta, the correlation remains positive (from

r = 0.10 to

r = 0.08). In Slovenia, the coefficient is strictly zero in 2009 and negative but very close to zero (

r = −0.01) in 2022. In Italy, Estonia, and Norway, the coefficients are negative but very close to zero and remain the same between 2009 and 2022. In Colombia, Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Latvia (in this order), the strength of the relationship between 2009 and 2022 increases. The increase is different across these countries, with the smallest in Colombia (from

r = 0.05 to

r = 0.07) and the largest in Latvia (from

r = −0.01 to

r = 0.08). In Sweden, the Netherlands, and Latvia, the association is becoming close to zero over time. In Chinese Taipei, the correlation changes its sign from negative to positive, but all coefficients are statistically insignificant. Statistically significant coefficients in countries where the strength of the correlation increases in 2022 are found only in Colombia, Bulgaria, and Latvia. Positive correlation coefficients are found in Malta, Colombia, the Netherlands, Bulgaria, and Latvia. Negative coefficients are found in all other countries.

The correlation coefficients between students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities and students’ trust in civic institutions scales are presented in

Table 4. In all countries in 2009, the association between the two scales is negative (i.e., the more students expect to participate in illegal protest activities, the less they tend to trust civic institutions or vice versa) and, in most cases (except for Chinese Taipei, Malta, and Bulgaria), statistically insignificant and close to zero. In 2016, the association between students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities and students’ trust in civic institutions scales is weaker than in 2009 and becomes close to zero in more cases (Lithuania, Chinese Taipei, the Netherlands, Latvia, Malta, and Bulgaria) compared to 2009, with the greatest decrease in the Netherlands (from

r = −0.13 to

r = −0.01) and Sweden (from

r = −0.21 to

r = −0.10).

In 2022, the correlations in most countries change to positive (i.e., the more students expect to participate in illegal protest activities, the more they tend to trust civic institutions), with the only exceptions in Estonia and Denmark, where the coefficients still remain negative but become closer to zero (i.e., weaken) compared to 2009 and 2016, although still remaining significant. In all other countries, the coefficients become positive, except for Sweden, where it is strictly zero (no relationship), and in Lithuania, Norway, the Netherlands, and Italy, the coefficients are very close to zero and statistically insignificant. The largest changes from 2009 to 2022 are in Denmark, Netherlands, Italy, Latvia, Slovenia, Malta, Sweden, Colombia, and Bulgaria, where the coefficients not only changed their direction but also their size. The greatest changes from 2009 to 2022 are in Colombia (from r = 0.05 to r = 0.27) and Bulgaria (from r = −0.03 to r = 0.19).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this article was to investigate the trends in students’ expectations to participate in illegal protest activities in countries participating in all three cycles of ICCS (2009, 2016, and 2022)—overall, by gender and by immigration background. The results on the countries’ overall trends show that students’ anticipation for participation in illegal protest activities increases in most participating countries, except for those in North Europe (Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, the Netherlands, and Sweden), where the levels remain stable over time and without increase. In these countries, the overall levels are also quite low. At first glance, these findings may seem to contradict those of

Ortiz et al. (

2022), who found that protests prevail greatly in middle-income and high-income countries. However, a key distinction is that while

Ortiz et al. (

2022) measure actual protest activity, our study examines anticipated participation in protests. Additionally, the age of the participants in this study (students in grade 8) differs significantly from the age of the protesters in

Ortiz et al. (

2022), representing a mix of various age cohorts. The increase in anticipated participation in illegal protest activities in our study is most notable in countries in South Europe (Italy, Malta, and Slovenia) and Colombia.

Among individual-level predictors, most studies (which do not focus on our target grade but are general) identify the following: (1) gender (women are less likely to participate in protest than men; although the gender gap in protest participation has declined in advanced societies, it is still visible), (2) age (approaches demonstrate that the age effect is consistently relevant to protest potential, whether the effect is negative or curvilinear), and (3) education (in a sense that better-educated people are more likely to engage in protest) as common sociodemographic predictors to attend protests (

Kwak, 2022), but those studies do not focus on illegal protest. In our study, we use civic knowledge as a proxy for education.

In general, civic knowledge achievement is associated negatively with students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities. This was found in most countries, but in countries in North Europe, the pattern is unclear—in some cases, lower levels of expectations to participate in illegal protest activities are associated with higher achievement and vice versa. This could mean that schools, which are important agents for acquiring civic knowledge, need to enhance curriculum development as well as practices in this area. And actually, it could suggest a nuanced interaction between civic knowledge and student attitudes toward political and societal activism (in different forms). This complexity underscores the need for schools, as pivotal agents in civic knowledge acquisition, to enhance their curriculum and pedagogical practices in civic and citizenship education (

Isac et al., 2011;

Hooghe & Dassonneville, 2011) with a special focus on different forms of social and political engagements. Moreover, the quality of civic and citizenship education—encompassing both the content delivered and the learning environment—has been shown to significantly impact students’ civic knowledge and engagement levels (

Isac et al., 2011;

Hooghe & Dassonneville, 2011). This is especially important, as findings from

Alscher et al. (

2022) suggest that fostering student engagement through cognitive activation is crucial for encouraging participation, with its impact mediated by political interest and knowledge, highlighting its greater importance over other teaching quality facets. Another finding from the literature supports the importance of civic knowledge; for example, “less politically knowledgeable citizens also tend to engage in illegal protest more frequently” (

Gil De Zúñiga & Goyanes, 2023, p. 1). Using data from 1960 to 2010 across 216 countries, an analysis performed by

Sawyer and Korotayev (

2022) shows that formal education increases anti-government protests in early development but reduces riots, especially later. As societies become more educated, protests rise but take more peaceful forms, as

Sawyer and Korotayev (

2022) predict. Their study also finds the strongest link between education and protests at early development stages, suggesting that secondary education plays a key role. Therefore, we could identify formal (compulsory) education as an especially important stage for civic engagement in the future. Education fosters tolerance, enhances human capital, and promotes social mobility, helping to mitigate destructive tendencies in protest movements (

Ustyuzhanin et al., 2023). Although our article focuses on the expected future participation of eighth graders in illegal protests, two points must be emphasized. First, school and civic and citizenship education play a crucial role in both present and future engagement in society, not just in legal/illegal protests. Second, expected or actual participation in society is often correlated in the literature with various individual factors of those who engage or predict their future engagement (this will be elaborated further in the next paragraph). Civic knowledge and engagement are interconnected, although it is not necessarily that civic knowledge would lead to engagement (

Galston, 2001), and also, contrary to findings from 50 years ago (authors annotation), recent research indicates that traditional classroom-based civic and citizenship education can greatly enhance political knowledge (

Galston, 2001). Further, well-informed students are more likely to participate in political life, such as voting or organizing civic initiatives; conversely, civic participation also enhances civic knowledge (

García-Cabrero et al., 2016). However, newer research (not necessarily on adolescents) shows a correlation between social media use and illegal protests. The link between social media and illegal protests is complex, shaped by factors such as previous protest involvement, political knowledge, and the psychological impact of authoritarianism.

Inguanzo et al. (

2021) highlight that both prior protest participation and social media news consumption strongly predict engagement in illegal protests, indicating that social media may activate underlying authoritarian tendencies and contribute to a more contentious political climate. Similarly,

Gil De Zúñiga and Goyanes (

2023) argue that platforms like WhatsApp can facilitate civil disobedience by increasing political awareness and mobilizing individuals for illegal protests. At the same time, a study on adolescents (ICCS 2022—which is also our target population, even more as they are the same students as in our study) shows that in most participating countries, students who used digital media for civic engagement (creating, sharing, commenting on, or liking online content about political or social issues) tended to have slightly lower civic knowledge (

Schulz et al., 2025). It is also important that students know how to identify true/reliable information on the internet. And as the results of the ICILS study (International Computer and Information Literacy Study) on eighth-grade students in 2023 showed, only 24% of students internationally were able to identify at least one thing they could do to check whether a website was a reliable source of information (

Fraillon, 2024). All this indicates how important it is to strengthen not only offline engagement among young people but also online engagement and how crucial digital citizenship education is. The latter is defined as “the empowerment of learners of all ages through education or the acquisition of competences for learning and active participation in a digital society to exercise and defend their democratic rights and responsibilities online, and to promote and protect human rights, democracy, and the rule of law in cyberspace” (

Council of Europe, n.d.), which is clearly connected with civic engagement in more general terms.

Concerning student gender, the general trend across the participating countries is that male students have a higher anticipation of participating in all cycles. However, in nine countries (Colombia, Estonia, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, and Sweden), the gap between male and female students is shrinking over time. It is notable that in countries located in North Europe (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden), the trends are decreasing or staying at the same levels for male students while increasing for female students. In Colombia, Italy, and Slovenia, on the other hand, the trends are increasing levels for both female and male students. In Bulgaria and Denmark, the gaps between male and female students are unchanged, but the trends in the levels of anticipated participation in illegal protest activities are moderately increasing for both genders. In Chinese Taipei, the gaps between female and male students are slowly increasing due to increasing expectations of male students and decreasing expectations of female students in 2022. Overall, the trends observed across these diverse contexts underscore the multifaceted nature of gender dynamics, including in education. The variations in anticipation levels among male and female students across different countries may suggest that educational policies and cultural contexts play critical roles in shaping these experiences. However, we should not attribute everything solely to education, as it is most likely a matter of highly complex contexts. For example,

Banaszak et al. (

2021) discovered that nations with greater gender equality exhibit smaller gender disparities in protest participation. This suggests that women’s participation in protests, including illegal ones, may have broader societal implications, potentially reshaping gender norms and expectations. Additionally, the motivations for engaging in illegal protests can vary significantly between genders.

Inguanzo et al. (

2021) examine the impact of authoritarianism on individuals’ decisions to participate in illegal political protests, highlighting that while both men and women may be motivated by a desire to resist oppressive systems, the way they express this opposition can vary depending on gendered experiences and societal expectations. When discussing protest engagement, the literature shows that collective action is typically male-dominated, with men favoring confrontational tactics like protests, while women are more inclined toward non-confrontational methods such as petitioning, reflecting key differences in participation patterns (

Dodson, 2015;

Isaacson, 2024), and this is also characteristic of young people (

Grasso & Giugni, 2022). All of this points to highly complex and overlapping contexts when interpreting gender differences in protests, including illegal ones.

When it comes to immigration background, the overall trends across the countries show that, in general, students with an immigrant background have higher expectations to participate in illegal protest activities. The only exception to this is Lithuania, where in 2009 and 2016, the expectations of students with an immigrant background were lower than those of the students without an immigrant background, but the differences are small and insignificant. In 2022, however, the differences become larger (students with an immigrant background are higher) and statistically significant. Over time, the gap widens in Denmark, Lithuania, Norway, the Netherlands, Slovenia, and Sweden. All of these countries, except for Slovenia, are located in North Europe. On the other hand, in Malta and Colombia, the gap is shrinking. In Colombia, this is due to the rising expectations of students without an immigrant background to participate in illegal protest activities, which reaches the levels of the expectations of students with an immigrant background. In Malta, this is due to the steadily declining expectation levels of students with an immigrant background. The involvement of adolescents with immigrant backgrounds in protests, including illegal ones, is likely a multifaceted issue influenced by their backgrounds, experiences, and the sociopolitical environment they navigate. In fact, outside the ICCS study, there is a lack of research in this area, especially regarding adolescents with an immigrant background (not those being immigrants) and their expected participation in illegal protests.

Understanding why people become politically engaged requires considering not only their actual competencies but also their perception of their own competence (

Matthieu & Junius, 2024). The relationship between students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities and their citizenship self-efficacy changes its strength increasingly over time in about half of the countries. The coefficients are positive in all countries (i.e., the higher the expectations to participate in illegal protest activities, the higher the citizenship self-efficacy tends to be). Interestingly, in some countries, the correlations between students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities and their interest in political and social issues are negative (i.e., higher expectations for participating in illegal protest activities are associated with low interest in political and social issues), while in others, they are positive (i.e., higher expectations for participating in illegal protest activities are associated with higher interest in political and social issues). Also, these change over time, and while in most countries, the associations were negative in 2009, in 2022, in most countries, they were positive. In countries in North Europe (Denmark, Estonia, Norway, and Sweden), the associations remain negative or become close to zero over time. Similarly, the association between students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities and their trust in civic institutions was negative in 2009 and, over time, became positive in almost all countries. In countries in North Europe (Denmark, Estonia, Lithuania, Norway, the Netherlands, Sweden), the association approaches zero over time. This is in line with another study that used the longitudinal data of students aged 14–17 (where second-wave data collection was conducted 1.5 years later)—results showed that the changes in adolescents’ readiness for non-normative participation (such as readiness to confront social rules for political reasons) were predicted by their lower institutional trust (

Šerek et al., 2018).

Compared to other countries in this study, Colombia and Chinese Taipei show rather different results. This is not unexpected, as the rest of the countries have a lot in common with each other, being situated in Europe. These differences are probably due to historical, cultural, and political differences. Differences, however, also appear across the European countries in this study. While students’ expectations to participate in illegal protest activities show increasing trends in countries located in the south of Europe, in countries in the north, the trends are rather stable, i.e., without change over time. Furthermore, the gaps in students’ expectations are closing between female and male students due to the decreasing expectations of male students and the increasing expectations of female students. This is rather different from countries located in the south of Europe, which show increasing trends for both genders. These differences are also visible in the expectations by migration background, where, mostly in countries located in North Europe, the expectations of students with an immigrant background increase, and the gap with the rest of the students increases as well. In most countries in the north of Europe, the strength of association between students’ expectations for participation in illegal protest activities and interest in political and social issues decreases and approaches zero over time, but this trend is not observed in the rest of the countries in this study. Similarly, in all countries in North Europe, the association between students’ expected participation in illegal protest activities and their trust in civic institutions changes from negative to positive over time. Malta shows rather different trends from all countries in this study.

5. Conclusions, Limitations of Our Study, and Possible Further Research

The results of our article show the important profiling of students who are more inclined to participate in illegal protests together with trend changes in investigated societies. These findings can inform the development of curricula and teaching strategies (in investigated countries) that promote critical thinking, ethical decision-making, and constructive civic engagement. The findings pay special attention to the importance of addressing why some students lean toward illegal protests by exploring their social environments, perceived lack of agency, or distrust in institutions. Additionally, the results also suggest the need to integrate lessons on peaceful advocacy, conflict resolution, and democratic processes to channel student activism into lawful and impactful forms of participation and engagement. One of the key implications of our results is the need to integrate lessons on peaceful advocacy and conflict resolution into school curricula (if they are not). The fact that lower civic knowledge is often associated with higher expectations of participation in illegal protest activities suggests that students may lack awareness of lawful and effective means of political engagement. Schools must, therefore, ensure that civic and citizenship education programs (subjects or whole-school approach) equip students with knowledge and skills to advocate for change within democratic frameworks. Lessons on peaceful advocacy could include historical and contemporary examples of nonviolent movements that have successfully led to social and political transformation, such as recent youth-led climate movements. Conflict resolution skills are particularly vital in this context, as protests—whether legal or illegal—often emerge from unresolved societal tensions. Teaching students negotiation, mediation, active listening skills, and cooperation among them (including solidarity of different forms) can help them develop the ability to engage in constructive dialogues rather than resorting to confrontational tactics. This aligns with previous research showing that fostering student engagement through cognitive activation—rather than just passive knowledge transmission—enhances their ability to participate meaningfully in civic life (

Alscher et al., 2022). In addition to peaceful advocacy, it is crucial that students understand the democratic processes available for civic engagement. Civic and citizenship education should also emphasize participatory democracy, explaining mechanisms such as petitions, referenda, community organizing, and policy advocacy. Encouraging students to take part in school-based civic initiatives, such as student councils, model parliaments, and youth advisory boards, can provide practical experiences in democratic decision-making. Moreover, partnerships between schools and local governments could help students see how civic participation translates into real-world impact, reinforcing the idea that engagement within legal frameworks can be effective. Our article also points to the increasing role of digital media in shaping students’ engagement with social and political issues. While social media can facilitate civic participation, it also carries risks, including misinformation and the amplification of extreme viewpoints. The findings from the ICILS study (

Fraillon, 2024) demonstrate that a significant proportion of 8th graders lack the skills to assess the credibility of online sources, making them more susceptible to manipulative narratives. Given this, digital citizenship education should be one of the key components of civic and citizenship learning. Schools should teach students how to critically evaluate information, engage in fact-checking, and recognize biased or misleading content. In addition, lessons on responsible digital activism can help students understand how to use online platforms for advocacy in ways that align with democratic principles. Rather than promoting illegal protest activities, social media can be harnessed for awareness campaigns, online petitions, and organizing lawful demonstrations. By equipping students with digital literacy skills (including civic and citizenship topics), educators can help mitigate the negative influence of online misinformation while promoting ethical and constructive online engagement. All this can help educators foster a sense of empowerment and responsibility while addressing the underlying causes of disengagement or radicalization. However, the complex interplay between civic and citizenship education, sociopolitical factors, and adolescent’s engagement in illegal protests needs to be recognized. While civic and citizenship education has the potential to foster informed and engaged citizens, the realities of socio-economic conditions, political climates, and digital influences complicate this landscape. As such, educators and policymakers must consider these multifaceted dynamics to effectively nurture civic engagement among youth. However, civic and citizenship education alone may not be sufficient if young people feel that their voices are not heard or that legal avenues for political engagement are ineffective.

This study comes with limitations. While the civic knowledge scale is concretely measured with a test, on the contrary, other variables are self-reported. However, the very important limitation of this study is the absence of a discussion regarding the general political climate in the various countries participating in the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) over the course of its three cycles (2009, 2016, and 2022). The political context can significantly influence students’ attitudes and expectations toward civic participation, including their anticipation of engaging in illegal protests. For instance,

Kitanova (

2019) highlights that contextual factors, such as the political environment and youth political participation, can vary widely across countries, potentially impacting the levels of civic engagement among adolescents. This is why we would like to raise this limitation, as understanding these contextual influences is, therefore, crucial, as they may correlate with the trends observed in students’ anticipated participation in illegal protests. The lack of this analysis may limit the generalizability of the findings and the ability to draw comprehensive conclusions about the factors influencing youth activism (in illegal protests) across different political landscapes.

There is also the question of whether examples of illegal protests in the ICCS study should be replaced or renewed, although this would mean no more trends. However, the discussion on illegal but legitimate protests could add value to the research. Yet, we fear that this might make international comparisons impossible.

Future research should aim to incorporate an analysis of the political climate in the participating countries during the ICCS study periods. This could involve examining how changes in government policies, political stability, and public sentiment toward civic engagement influence students’ expectations and behaviors regarding protests. However, future research could investigate the role of civic and citizenship education in shaping students’ attitudes toward different forms of engagement. Additionally, longitudinal studies that track the political socialization of adolescents in relation to their civic engagement with a focus on illegal protests could provide valuable insights.