Developing Coaches Through a Cognitive Apprenticeship Approach: A Case Study from Adventure Sports

Abstract

1. Introduction

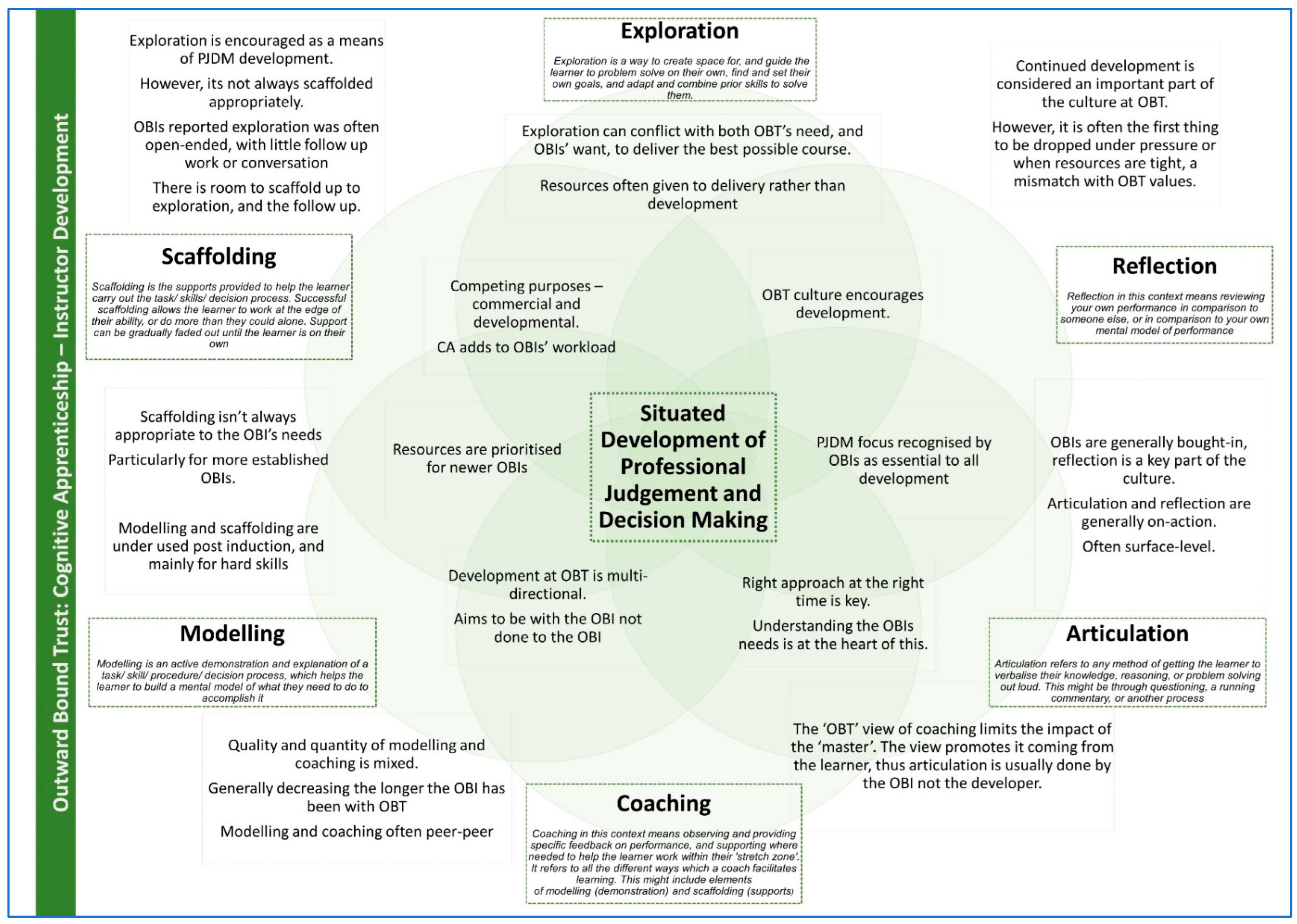

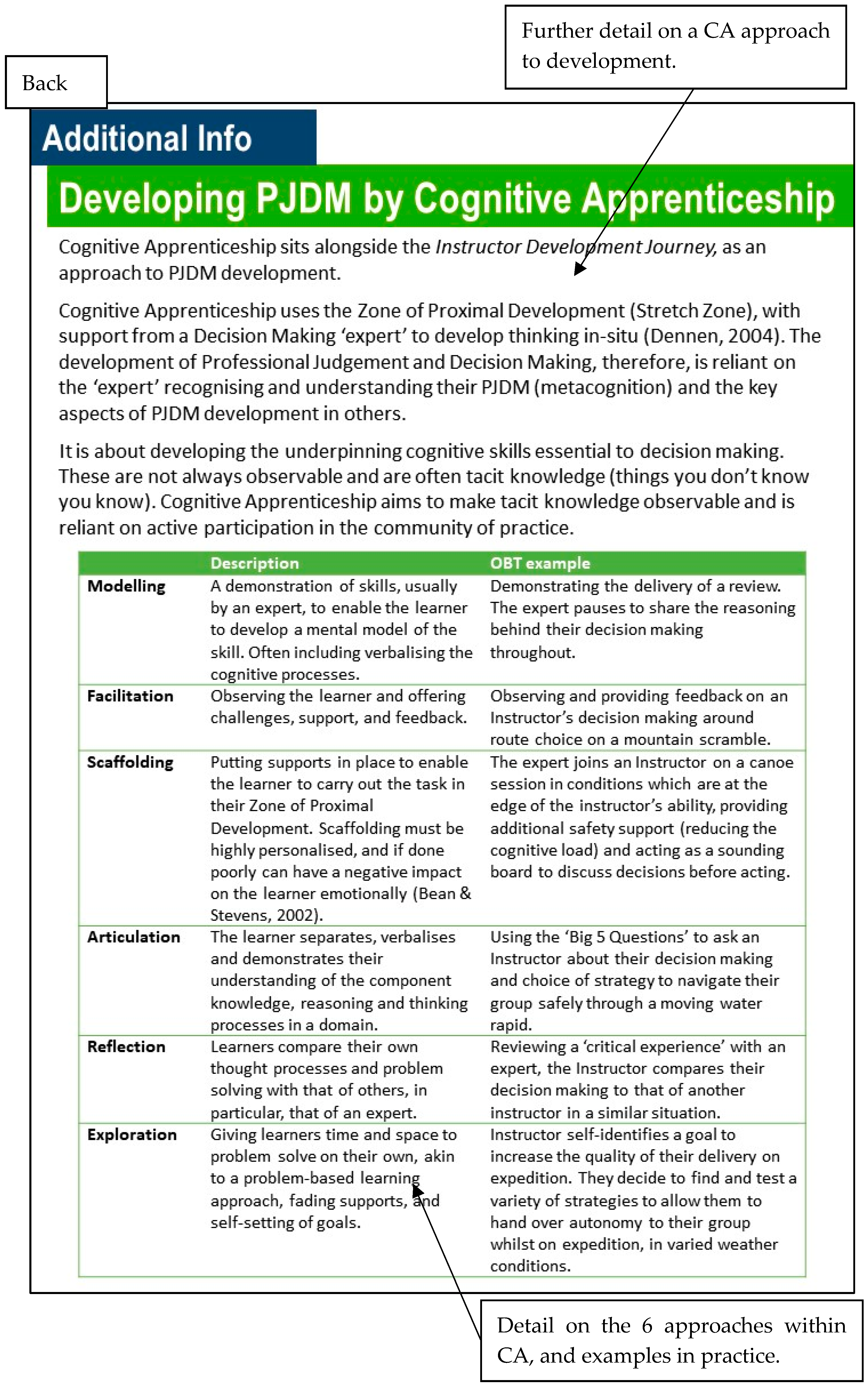

1.1. Cognitive Apprenticeship

Utilisation of the CA Approach

1.2. The Trust’s Coaches–Characteristics and Context

1.3. PJDM and the Trust’s Coaches

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phase 1: Survey

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Procedure

2.1.3. Analysis

2.2. Phase 2: Focus Group

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Procedure

2.2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1

3.1.1. Developmental Needs of the Coach in Conflict with Organisational Needs

During staff canoe training we were shown how to construct canoe sails. The trainer found a calm space (both physical and time) to explain and demonstrate… The explanation enabled me to understand the how and why and the risks involved.

I was given the space to take ownership of my own exploration and CPD, however there could be more meetings with line managers. Sometimes I feel a bit out of the loop… I don’t think that the, kind of, self-led works for me. Mostly because we’re so busy here, there’s so much going on for me and I feel like I’m still learning lots.

While the pass-out system provides a scaffold to allow people to operate inside and at the edge of their comfort zones, sometimes it can feel like a barrier to being allowed to run activities that are well within your skillset and comfort zone.

As a new instructor I feel a lot of time is going into adjusting and focusing on the basics and just getting by. I find it hard to add time for extra exploration into learning models and research, in between managing a group and pass-outs.

3.1.2. Developmental Culture

This community CA approach aligned with the Trust’s developmental culture, fostering a sense of development being done with, rather than done to the coach. OBC42 described an example of scaffolded development, demonstrating the effectiveness of the well-applied CA approach and a shift in ownership of development from LAM to coach, leading to a pass-out:I was able to work with another [coach] … they coached me in the pros and cons of bellringing techniques over belay devices… at the end of the session, they gave good constructive feedback on my session and then shared what they would have done differently. I really liked this.(OBC52)

However, this example was not the universal experience of the participants. Some of the LAMs appeared more skilled than others with the CA approach, highlighting the need for a more intentional approach to PJDM development and further training for LAMs in applying the CA approach.I had no experience of rowing sessions before starting at Outward Bound … I shadowed a couple of rowing sessions, including one run by [a LAM] where afterwards we had a sit-down chat about the session, and I got the opportunity to ask any questions about how they had run things. A few weeks later [the LAM] encouraged me to invite them along for another rowing session, which they offered to let me run and then provide feedback for me, before I did a pass-out. The next opportunity I had after that to row I had a successful pass-out.

3.2. Phase 2

3.2.1. Acknowledgement of the Current Status of PJDM Development

3.2.2. A Purposeful and Intentional Approach to PJDM Development

4. Discussion

4.1. Aligning Outward Bound Trust Values and Practice in Coach Development: A Situated Development in a Hyperdynamic Workplace

4.2. A Shared Mental Model of Development

4.3. How Can the Outward Bound Trust Work Toward an Intentional CA?

- (1)

- A facilitated day of training by a subject matter ‘expert’. The first half of the training involves technical input on the key components of the coaches’ PJDM to support an understanding of the components to be developed in the coaches. Participants in the training then reflect on the coaches’ practices and on their own experiences and share examples with the group, supporting the development of a shared mental model. The second half of the day focusses on the process of development, introducing the CA approach and teaching methods (modelling, coaching, scaffolding, articulation, reflection, and exploration). It follows a similar process of input, discussion, reflection, and sharing. At the end of the training, participants identify a specific area of growth, individual to them, to explore further, based on their reflection on their own practice throughout the day. For example, to develop own articulation and to support more experienced coaches to develop their articulation.

- (2)

- Supported self-directed development. Paired with a Head of Learning and Adventure, Learning and Adventure Managers work on their personal actions, observing others’ practices (modelling), offering them feedback on their observations (coaching), discussing (articulation) throughout the day, and making explicit links to the content of the training. The pair will reflect on the session together, and they may choose to use the ‘big 5’ questions (D. Collins & Collins, 2020) as an initial guide. At a later date, they will switch, and the Learning and Adventure Manager will explore ways of working with a coach to develop an aspect of their PJDM, scaffolding their development at both macro (6 months) and micro (session) levels. The Head of Learning and Adventure challenges the Learning and Adventure Manager to operate in their zone of proximal development (scaffolding), offers feedback throughout the day (coaching), and encourages articulation of rich descriptions of the situation (articulation) (L. Collins & Collins, 2022).

- (3)

- Continued self-directed development within the role. The Learning and Adventure manager continues to explore ways to develop coaches’ using the CA approach, individualised to each coach. Learning and Adventure managers are encouraged to share their experience of their own developments with each other, ask questions (articulate and reflect), and gain feedback and support (coaching and scaffolding). This is done across centres, via video call, to support the development of a shared mental model across the OBT as a whole. At these sessions, Learning and Adventure Managers also review the initial targets set and establish new areas to explore.

- (4)

- Peer-supported development. Learning and Adventure Managers pair up with one another and work with a coach for a second day of modelling and coaching each other. They follow a similar process to the previous targeted development day (stage 2), comparing their practice feedback that focuses on their use of the appropriate method at the right time for the individual to allow the coach to work within their zone of proximal development and scaffolding of the coaches’ cognitive load.

- (5)

- A facilitated day of training by a subject matter ‘expert’. Around 6 months later, a second training day reviews the progress made and offers additional support individually to each Learning and Adventure Manager. The input in this training session focuses on the developmental culture within the Trust. The technical input focuses on the community of practice, the importance of personal and professional experience, and adaptive expertise.

- (6)

- Cyclical continued development. Stages 3 and 4 are repeated, overseen, and supported by the Head of Learning and Adventure. Learning Adventure Managers continue their development in skilfully applying the CA approach as the new aspects of their practice become embedded. The discussions, reflections, articulation, and curiosity about the way in which others work become a natural aspect of the community of practice and support a continued development.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Algarra, N. N., McAuliffe, J. J., & Seubert, C. N. (2020). Neuroanesthesiologists as interoperative neurophysiologists: A collaborative cognitive apprenticeship model of training in a community of clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing, 34(2), 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashford, M., Taylor, J., Payne, J., Waldouck, D., & Collins, D. (2023). “Getting on the same page” enhancing team performance with shared mental models—Case studies of evidence informed practice in elite sport. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, 1057143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkham, P. (2020, December 13). Outdoor education centres warn of risk of closure due to COVID. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/dec/13/outdoor-education-centres-warn-of-risk-of-closure-due-to-covid (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Barkham, P. (2021, March 23). “We’ve fallen off the radar”: Outdoor centres in crisis over lack of COVID help. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/mar/23/outdoor-education-centres-crisis-lack-covid-support (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Barry, M., & Collins, L. (2021). Learning the trade–recognising the needs of aspiring adventure sports professionals. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 23(2), 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, T. W., & Stevens, L. P. (2002). Scaffolding Reflection for Preservice and Inservice Teachers. Reflective Practice, 3, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon-Bowers, J., Salas, E., & Converse, S. (1993). Shared mental models in expert team decision making. In N. Castellan (Ed.), Individual and group decision making: Current issues (pp. 221–246). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, K., Stalmeijer, R. E., Könings, K. D., Segers, M., & van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (2014). How experts deal with novel situations: A review of adaptive expertise. Educational Research Review, 12(1), 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallerio, F., Wadey, R., & Wagstaff, C. R. D. (2020). Member reflections with elite coaches and gymnasts: Looking back to look forward. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 12(1), 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancey, W. J. (1995). Situated cognition: How representations are created and given meaning. In R. Lewis, & P. Mendelsohn (Eds.), Lessons from learning (pp. 231–242). North Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, A. (2005). Cognitive apprenticeship. In R. Sawyer (Ed.), The cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 47–60). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A., Brown, J., & Holum, A. (1991). Cognitive apprenticeship: Making thinking visible. American Educator, 15(3), 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, A., & Stevens, A. (1991). A cognitive theory of inquiry teaching. In P. Goodyear (Ed.), Teaching knowledge and intelligent tutoring (pp. 203–230). Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, D., Burke, V., Martindale, A., & Cruickshank, A. (2014). The illusion of competency versus the desirability of expertise: Seeking a common standard for support professions in sport. Sports Medicine, 45(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, D., & Collins, L. (2020). Developing coaches’ professional judgement and decision making: Using the ‘Big 5’. Journal of Sports Sciences, 39(1), 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, D., Taylor, J., Ashford, M., & Collins, L. (2022). It depends coaching—The most fundamental, simple and complex principle or a mere copout? Sports Coaching Review, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D., Willmott, T., & Collins, L. (2018). Periodization and self-regulation in action sports: Coping with the emotional load. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(1652), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L., & Collins, D. (2015). Integration of professional judgement and decision-making in high-level adventure sports coaching practice. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(6), 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, L., & Collins, D. (2016). Professional judgement and decision-making in the planning process of high-level adventure sports coaching practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 16(3), 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L., & Collins, D. (2017). The foci of in-action professional judgement and decision-making in high-level adventure sports coaching practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 17(2), 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L., & Collins, D. (2022). The role of situational awareness in the professional judgement and decision-making of adventure sport coaches. Journal of Expertise, 5(4), 117–131. Available online: https://journalofexpertise.org/articles/volume5_issue4/JoE_5_4_Collins_Collins.html (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano-Clark, V. L. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshank, A., & Collins, D. (2017). Beyond ‘crude pragmatism’ in sports coaching: Insights from C.S. Peirce, William James, and John Dewey: A commentary. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 12(1), 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennen, V. P. (2004). Cognitive Apprenticeship in Educational Practice: Research on scaffolding, modeling, mentoring, and coaching as instructional strategies. In D. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 813–828). Lawrence Erlbaum & Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Eastabrook, C., & Collins, L. (2021). What do participants perceive as the attributes of a good adventure sports coach? Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 21(2), 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M. R. (1995). Measurement of Situation Awareness in Dynamic Systems. Human Factors, 37(1), 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, B. C., McGee, S., Schwartz, N., & Purcell, S. (2000). The experience of constructivism: Transforming teacher epistemology. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 32(4), 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (1982). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R., & Casey, M. (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kuusela, H., & Paul, P. (2000). A comparison of concurrent verbal protocol analysis retrospective. The American Journal of Psychology, 113(3), 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation (Learning in doing: Social, cognitive and computational perspectives). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofland, J., Snow, D. A., Anderson, L., & Lofland, L. H. (2006). Analyzing social settings: A guide to qualitative observation and analysis (4th ed.). Thompson Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Martindale, A., & Collins, D. (2005). Professional judgment and decision making: The role of intention for impact. Sport Psychologist, 19(3), 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martindale, A., & Collins, D. (2012). A professional judgment and decision making case study: Reflection-in-action research. The Sport Psychologist, 26, 500–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, H. (1996). Situated learning perspectives. Educational Technology Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mees, A. (2024). Developing “it depends” in the wild: An exploration of outdoor instructors’ professional judgement and decision making and its development in the outward bound trust. University of Edinburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Mees, A., & Collins, L. (2022). Doing the right thing, in the right place, with the right people, at the right time; a study of the development of judgment and decision making in mid-career outdoor instructors. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 24(3), 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mees, A., Sinfield, D., Collins, D., & Collins, L. (2020). Adaptive expertise—A characteristic of expertise in outdoor instructors? Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 25(4), 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mees, A., Toering, T., & Collins, L. (2021). Exploring the development of judgement and decision making in “competent” outdoor instructors. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 22(1), 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J. (2004). A handbook of reflective and experiential learning: Theory and practice. Routledge Falmer. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, G. (2010). Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 15(5), 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phonic.ai. (2023). Phonic. Infillion. [Google Scholar]

- Pimmer, C., Pachler, N., Nierle, J., & Genewein, U. (2012). Learning through inter- and intradisciplinary problem solving: Using cognitive apprenticeship to analyse doctor-to-doctor consultation. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 17(5), 759–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyani, M., & Sen, A. (2009). The tacit dimension (Revised). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics XM. (2023, March 22). Qualtrics. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Schommer, M. (1994). Synthesizing epistemological belief research: Tentative understandings and provocative confusions. Educational Psychology Review, 6(4), 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Stalmeijer, R., Dolmans, D., Wolfhagen, I., Muijtjens, A., & Scherpbier, A. (2010). The maastricht clinical teaching questionnaire (MCTQ) as a valid and reliable instrument for the evaluation of clinical teachers. Academic Medicine, 85(11), 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalmeijer, R., Dolmans, D., Wolfhagen, I., & Scherpbier, A. (2009). Cognitive apprenticeship in clinical practice: Can it stimulate learning in the opinion of students? Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14(4), 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioural sciences. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, B. (2009). Spatial cognition. In The cambridge handbook of situated cognition (pp. 201–216). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1977). The development of higher psychological functions. Soviet Review, 18(3), 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modelling |

|---|

| 1. LAMs demonstrated how to do things which were new to me |

| 2. LAMs created opportunities to observe them, or another instructor when appropriate |

| 3. LAMs served as a role model as to the kind of coach I would like to become |

| Coaching |

| 4. LAMs gave useful feedback during or after observation of my practice |

| 5. LAMs adjusted their level of coaching and support to my level of experience |

| 6. LAMs offered me sufficient opportunities to deliver sessions independently |

| Articulation |

| 7. LAMs asked me to provide a rationale for my actions and decisions |

| 8. LAMs asked me questions aimed at increasing my understanding and awareness |

| 9. LAMs encouraged me to explore my strengths and weaknesses |

| Exploration |

| 10. LAMs encouraged me to formulate goals for my development |

| 11. LAMs encouraged me to pursue the goals set for my development |

| Safe Learning Environment |

| 12. LAMs created a safe learning environment |

| 13. LAMs were genuinely interested in my development as an instructor |

| 14. LAMs showed that they respected me |

| Scaffolding | |

|---|---|

| Description of CA approach | Scaffolding is the support provided to help the learner carry out the task/skills/decision process. Successful scaffolding allows the learner to work at the limit of their ability, or do more that they could alone. Support can be gradually faded out until the learner is on their own. |

| Example Vignette | “The Learning and Adventure Manager was aware of my previous experience and offered me enough opportunity to work independently. I was encouraged to work within my ‘stretch zone’ rather than my ‘comfort zone’. I was supported with activities which were at the top end of my skillset, and the support was gradually reduced so that I could become more independent.” |

| Question 1 | Please describe generally your experiences of scaffolding over the past 12 months. Think about when, where, and how you experienced or engaged in scaffolding. You could compare to the example above if you prefer… |

| Question 2 | Describe a specific experience at Outward Bound during the past 12 months which demonstrates scaffolding. What impact did this have on your development as a coach? |

| Question 3 | In your experience, what are the challenges with scaffolding as part of your development at Outward Bound? |

| Question 4 | How do you think the process of scaffolding could be improved at Outward Bound? |

| CA Approach | Modelling | Coaching | Articulation | Exploration | Learning Environment | Total Score | N | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||

| Overall M | 3.18 | 2.78 | 3.18 | 3.87 | 4.02 | 4.02 | 3.8 | 3.75 | 3.35 | 3.4 | 3.07 | 4.22 | 3.76 | 4.16 | 50.56 | 55 |

| SD | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 1.13 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 1.23 | 1.03 | 1.14 | 0.90 | 10.66 | |

| Centre 1 | 3.64 | 3.00 | 3.27 | 3.73 | 3.91 | 3.82 | 4.18 | 4.00 | 3.36 | 3.45 | 3.27 | 4.36 | 3.45 | 4.18 | 51.64 | 11 |

| SD | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.28 | 1.12 | 1.34 | 1.20 | 1.21 | 0.75 | 11.03 | |

| Centre 2 | 2.77 | 2.31 | 2.77 | 3.54 | 3.62 | 4.00 | 3.38 | 3.00 | 2.85 | 3.00 | 2.92 | 3.77 | 3.46 | 3.77 | 45.15 | 13 |

| SD | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 1.05 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.15 | 0.80 | 1.08 | 1.12 | 1.16 | 1.39 | 1.09 | 10.98 | |

| Centre 3 | 2.60 | 2.80 | 3.60 | 3.40 | 4.60 | 4.80 | 3.00 | 3.80 | 3.40 | 3.60 | 3.20 | 5.00 | 4.60 | 4.60 | 53.00 | 6 |

| SD | 0.89 | 0.83 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.70 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 1.14 | 1.09 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 5.22 | |

| Centre 4 | 3.31 | 2.92 | 3.27 | 4.19 | 4.15 | 3.96 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.58 | 3.54 | 3.04 | 4.23 | 3.88 | 4.27 | 52.35 | 26 |

| SD | 1.08 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 0.93 | 1.01 | 1.34 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.31 | 0.90 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 10.67 | |

| Overarching Theme | Theme | Subtheme | Example Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental needs of the coach in conflict with the organisational needs of the Trust | Choosing the right approach at the right time for the coach | OBIs’ PJDM development was a consequence of the trainers’ PJDM around individualisation | I felt like it could possibly take away your autonomy (OBC16) |

| Appropriateness of timing when giving freedom and independence | I felt almost pushed to be independent straight after the induction phase (OBC12) | ||

| Lack of follow-up for exploratory PJDM development | These experiments are never checked or questioned (OBC13) | ||

| The quality and quantity of the CA approach decreased over time | I was given many opportunities to observe… however, after [the induction] this has dropped (OBC9) | ||

| Challenges of PJDM development situated in the workplace | Client needs were prioritised over development needs | I do think that [opportunities to work with] peers need to stop being used as resilience for the course and used as development (OBC50) | |

| Development conflicts with OBIs’ desire/the Trust’s need to do the job | If a time urgency suddenly turned up, it would be the modelling and the questions that took a hit (OBC20) | ||

| Developing PJDM through a CA added to the OBIs’ workload and cognitive demands | Under stress or time pressure it is easy to slide back into bad habits rather than modelling (OBC34) | ||

| Sound PJDM required to provide safety | It creates an opportunity for failure, which clearly creates limitations in its use with technical skill sets (OBC13) | ||

| Developmental Culture | Development as an organisational value | The learning environment | It’s self-generated with me. We use ’one note’ and I often write something up after a course. (OBC32) |

| Development was underpinned by quality of rapport between trainer and OBI | I want it to be authentic… All about building rapport for me and noticing when my ‘cup is full’ (OBC39) | ||

| OBIs value PJDM development | [The LAM] would give me freedom to make decisions and execute them, allowing me to reflect on the outcome then he would give advice or other options (OBC2) | ||

| A mismatch between values and actions | Rarely am I challenged by anyone to be a bit more reflective (OBC16). | ||

| A community approach to CA | PJDM development was multi-directional | I was able to work with another [OBC]… I really liked this style of coaching where they were empowering me (OBC52) | |

| PDJM development was done with the OBI, not to the OBI | I have had lots of encouragement to pursue qualifications such as sea kayak leader, canoe leader. I have been coached predominantly on the water by my line manager, who has challenged my thought process. (OBC42) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mees, A.; Collins, D.; Collins, L. Developing Coaches Through a Cognitive Apprenticeship Approach: A Case Study from Adventure Sports. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030288

Mees A, Collins D, Collins L. Developing Coaches Through a Cognitive Apprenticeship Approach: A Case Study from Adventure Sports. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):288. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030288

Chicago/Turabian StyleMees, Alice, Dave Collins, and Loel Collins. 2025. "Developing Coaches Through a Cognitive Apprenticeship Approach: A Case Study from Adventure Sports" Education Sciences 15, no. 3: 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030288

APA StyleMees, A., Collins, D., & Collins, L. (2025). Developing Coaches Through a Cognitive Apprenticeship Approach: A Case Study from Adventure Sports. Education Sciences, 15(3), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030288