1. Introduction

Schools are expected to strive for inclusive education (

UNESCO, 2008), which requires a systemic approach to education, ensuring structural changes in policies and legislation, attitudes, teaching and learning practices, and management and evaluation. Inclusive education might be particularly beneficial for gifted students, as it caters to the specific educational needs of individual students (

Ninkov, 2020). For a long time, extracurricular and differentiated instruction in the Netherlands focused on students with learning and behavioural problems, under the assumption that gifted students did not require additional educational support (

De Boer et al., 2013). Since then, various educational interventions for gifted students have been developed, such as acceleration (e.g.,

Hoogeveen, 2015) and enrichment (e.g.,

Van der Meulen et al., 2014). However, these interventions are often inadequate in practice, hindering gifted students from realising their full potential (

Wong & Morton, 2017).

UNESCO (

2008) highlighted the importance of a systemic approach to more inclusive education. The actiotope model of giftedness (

Ziegler, 2005) supports this systemic approach by considering the interaction between cognitive, non-cognitive, and environmental factors in the development of giftedness (

Ziegler & Phillipson, 2012). These environmental factors encompass the student’s school and home environments, including school leaders.

School leaders in gifted education play an important role in supporting, motivating, and inspiring others while maintaining high expectations for their programmes (

Haworth, 2020). School leaders who embody these attributes often lead highly regarded gifted education programmes, as they empower others, foster development, and advocate effectively for their gifted students. In the Dutch educational system, schools operate with significant autonomy, with policy development occurring primarily at the school board or individual school level. School leaders are thus crucial decision-makers, while overseeing school processes (

Neeleman, 2019). Consequently, school leaders have an important role in the system surrounding gifted students, as they possess greater capacity to implement school-wide measures that are tailored to the needs of gifted students.

The scientific literature currently lacks insights into how school leaders perceive their relationships with other involved actors in gifted education. This gap could be addressed by exploring school leaders’ perspectives on the involvement of and their interactions with parents, teachers, and other school leaders within the context of gifted education. Focusing on these specific actors is crucial, as they play integral roles in shaping and supporting education (

Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009). Therefore, understanding these relationships, along with the opportunities and challenges in strengthening support for gifted students, is essential for advancing this field of research.

Given that the concepts of involvement and interaction can differ significantly across countries and cultures, the current study defined these concepts using Dutch literature and the Dutch educational context. Therefore, involvement is understood as the active participation and engagement of teachers, parents, and other school leaders in shaping and supporting the gifted student’s educational development. It is not a fixed personal trait but emerges from dynamic exchanges between individuals and their environment (

Volman, 2011) and is considered one of the essential conditions for learning (

Mascareño Lara et al., 2023). Central to this involvement is a collaborative, non-obligatory partnership between the school and home, always in the best interest of the student (

Flinkevleugel & Eenshuistra, 2017). Interaction, in the current study, refers to the continuous process of communication and reciprocal exchange between these key actors (parents, teachers, and other school leaders). Effective communication is essential for establishing a strong collaborative partnership between the school and home, helping to prevent misunderstandings and to avoid educational problems (

Herweijer & Vogels, 2013). Understanding school leaders’ viewpoints on the involvement of multiple actor groups and interactions with these actor groups could provide valuable insights into both the opportunities and challenges for enhancing and sustaining mechanisms supporting gifted education.

Collaboration refers to the process where individuals engage in joint activities, such as exchanging ideas and experiences, with the aim of achieving individual and shared learning outcomes. In the context of education, collaboration encompasses various forms of interaction, ranging from providing assistance to joint work and collegial support. These activities can lead to changes in knowledge, beliefs, and behaviour, both at the individual and group levels (

Doppenberg et al., 2012).

VanTassel-Baska and Johnsen (

2007) emphasised the importance of collaboration and advocacy among gifted educators, school leaders, and parents for effecting change in gifted education. The Council for Exceptional Children (

CEC, 2024) recently published the ‘CEC Initial Practice-Based Professional Preparation Standards for Gifted Educators’. Standard 7, ‘Collaborating with other Stakeholders’ also underscores the importance of collaboration with educational professionals, families, and service providers to facilitate effective educational support for gifted students.

Parents are often the most prominent actors in the home environment of gifted students. Parental support positively impacts the motivation of gifted students (

Al-Dhamit & Kreishan, 2016), and helps them realise their full potential (

Renati et al., 2022). School leaders also recognise parental involvement as crucial for educational improvement and success (

Ishimaru, 2019). Furthermore, systemic approaches suggest that interactions within a gifted student’s system, including family and educational actors, can impact talent development (

Ziegler & Stoeger, 2017). Despite this understanding, there remains a noticeable gap in the literature regarding school leaders’ perspective on parental involvement and their interactions with parents, particularly in the context of gifted education.

Teachers can be seen as the most prominent actors in the school environment of gifted students, playing an important role in, e.g., identifying gifted students (

Golle et al., 2023) and providing a challenging learning environment (

Steenberghs et al., 2023). Creating this environment, including implementing educational interventions, necessitates clear policies (

Subotnik et al., 2011). Teachers are responsible for putting these policies into practice, which requires clear directions from policymakers, such as school leaders (

Mills et al., 2014). Maintaining positive relationships between school leaders and teachers not only facilitates this process, but it also significantly impacts the overall school environment, influencing, for example, job satisfaction and attitudes (

Price, 2012). Although the need for collaboration and interaction between teachers and school leaders seems clear, little empirical evidence exists on these topics, especially in the context of gifted education. Understanding the mechanisms and conditions underlying these dynamics could provide valuable tools for educators to sustain effective change and enhancement for gifted students.

In addition to school leaders’ relationships with parents and teachers, their relationships with other school leaders are also crucial. Despite the traditional focus on improving individual schools,

Jones and Harris (

2014) emphasised that school leaders should invest in disciplined professional collaboration, which fosters shared leadership and facilitates lasting organisational change. While

Jones and Harris (

2014) focused on general education, this principle is especially relevant in gifted education, because gifted students often require both cross-classroom and cross-school measures to ensure appropriate and cost-effective education.

VanTassel-Baska and Johnsen (

2007) specifically highlighted the necessity of collaboration among educators, administrators (such as school leaders), and parents to effect change in gifted education and better support gifted students. By collaborating, school leaders can create a more cohesive and effective educational environment that benefits gifted students. However, there is still little research focused on school leaders’ involvement and their interactions with each other, particularly in the context of gifted education. Understanding these dynamics could be fundamental for enhancing gifted education and support.

2. Current Study

The current study focused on school leaders’ perceptions regarding the involvement of and interactions with other key actors, i.e., parents, teachers, and other school leaders, in the context of gifted education. Additionally, potential relationships between involvement and interactions with these key actors were explored. Given the limited understanding of the underlying mechanisms and conditions related to the involvement of and interactions with these environmental actors, the current study also examined perceived facilitators and barriers to involvement and interactions as perceived by school leaders. Employing an exploratory (mixed-method) approach, this study aimed to provide valuable insights to enhance inclusive primary and secondary education for gifted students.

The first set of research questions (RQs) delved into school leaders’ perspectives regarding the involvement of different actors in gifted education:

To what extent do school leaders perceive the involvement of parents, teachers, and other school leaders, and how satisfied are school leaders with these levels of involvement?

Is there a relationship between school leaders’ perceptions of involvement of parents, teachers, and other school leaders, and their satisfaction levels with this involvement?

What factors do school leaders perceive as facilitators or barriers to effective involvement of parents, teachers, and other school leaders?

The second set of RQs explored the interactions between school leaders and different actors in gifted education:

- 4.

To what extent do school leaders perceive interactions with parents, teachers, and other school leaders, and how satisfied are school leaders with these interactions?

- 5.

Is there a relationship between school leaders’ perceived number of interactions with parents, teachers, and other school leaders, and their satisfaction levels with these interactions?

- 6.

What factors do school leaders perceive as facilitators or barriers to effective interactions with parents, teachers, and other school leaders?

The final set of RQs investigated school leaders’ perceived relationships between the involvement of and interactions with different actors in gifted education:

- 7.

Is there a relationship between school leaders’ satisfaction with involvement and satisfaction with interactions with parents, teachers, and other school leaders?

- 8.

How do school leaders perceive the relationship between their satisfaction with involvement and their interactions with parents, teachers, and other school leaders?

4. Results

4.1. Involvement of Actors and Satisfaction with Involvement

Table 2 presents the perceptions of school leaders regarding the involvement and satisfaction levels with the involvement of parents, teachers, and other school leaders in gifted education (RQ1). On average, school leaders rated parental involvement with mean scores ranging from “neutral” to “involved”, teacher involvement from “involved” to “very involved”, and other school leaders’ involvement from “not involved” to “neutral”. Mean satisfaction levels across all actor groups ranged from “neutral” to “satisfied”.

Results from repeated measures ANOVA tests unveiled differences participants perceived among the actor groups concerning perceived involvement. The assumption of sphericity was violated for involvement (Mauchly’s test; p < 0.001), necessitating the use of Huynh-Feldt correction due to an Epsilon greater than 0.75. A significant effect of actor group was observed, F(1.57, 158.80) = 52.31, p < 0.001, indicating a large effect, partial η2 = 0.341. Simple contrasts revealed that school leaders perceived teachers as significantly more involved compared to both parents (p =< 0.001; partial η2 = 0.236) and other school leaders (p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.437) in gifted education. Furthermore, school leaders perceived parents as significantly more involved than other school leaders (p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.244) in gifted education.

The assumption of sphericity was met for satisfaction levels (Mauchly’s test; p = 0.675). No significant effect of group was found, F(2, 164) = 2.12, p = 0.124, indicating no discernible differences in school leaders’ satisfaction levels with the perceived involvement of parents, teachers, and other school leaders in gifted education.

4.2. Relationship Between Involvement and Satisfaction with Involvement

Simple linear regression analyses unveiled significant relationships between school leaders’ perceived involvement of and satisfaction levels in gifted education across all actor groups (RQ2).

Table 3 presents these relationships, highlighting large effect sizes. These findings underscore that larger perceived involvement of actors was positively correlated with increased satisfaction among school leaders in gifted education.

4.3. Facilitators and Barriers to Involvement

4.3.1. Facilitators to Involvement

Interview participants were asked to identify factors facilitating the involvement of the various actor groups, i.e., parents, teachers, and other school leaders (RQ3). These facilitators are detailed in

Table 4, alongside descriptive statistics. Quotes representing each facilitator are presented in

Supplemental Table S1. The following results focus on the three most frequently mentioned facilitators.

For parental involvement, the most frequently mentioned facilitator was “Approachability”, with one school leader commenting:

Give the opportunity to also respond to this via email. You can open a response window there, so it is very accessible to communicate about this to parents. That can be done quite easily. That this does have a positive effect on parental involvement in general.

The second most frequently mentioned facilitator was “Willingness”, exemplified by the quote, “Well, that sounding board, quite a lot of parents have responded to it, and they also said to each other, ‘Hey, maybe I should start a WhatsApp group.’”. The third most frequently mentioned was “Open Communication”, with a school leader mentioning: “... I find those parents to be very constructive in their criticism. It’s not about criticising us or saying we’re not doing well, but more about thinking together, ‘What can we all do?’ I found that approach very constructive.”.

Focusing on the teachers’ involvement, the most frequently mentioned facilitator by school leaders was “Willingness”. One school leader illustrated this by saying:

The willingness is there because they really want to. And also how they are experimenting with it and what they already offer, because it’s not that they want to but do nothing. A lot is happening in the classroom in terms of extra work, yes.

This was followed by “Student-Centredness”, as expressed by a school leader: “That we have eyes for the well-being of every child.”. Lastly, “Knowledge(sharing)” was third most frequently mentioned, with one school leader stating:

And well, the expertise was partly gone. And I really think that’s a very strong point, that a group of colleagues really took it upon themselves and started building together. And well, the expertise that has been built up over the past years and the experience, that is really invaluable.

Concerning other school leaders’ involvement, “Collaboration” was the most frequently mentioned facilitator. One school leader described it as follows: “We exchange information between schools on what we are working on, how we approach things and how they approach things, and exchanging developments. I think that’s just very valuable.”. The second most frequently mentioned facilitator was “Policy”, illustrated by this quote: “... the schools within a school board have now written down those core values, and in my opinion, those core values provide enough guidance to work on that piece of customisation and to work with that piece of gifted education.”. “Willingness” was the third most frequently mentioned facilitator. One school leader expressed: “… I have never encountered resistance or a fragment of it, such as ‘Well, these students manage fine, so we don’t find it necessary.’”.

4.3.2. Barriers to Involvement

To conclude the answering of RQ3, interview participants were asked to identify perceived barriers to the involvement of the different actor groups. The mentioned barriers, along with descriptive statistics, are detailed in

Table 5. Quotes illustrating each barrier are provided in

Supplemental Table S2. The following results focus on the three most frequently mentioned barriers.

The most frequently mentioned barrier to parental involvement was “Lack of Knowledge(sharing)”. One school leader stated:

Yes, let me think. Yes, I have the impression that some parents sometimes cannot fully understand their child, or don’t fully get it. That understanding is a bit difficult. Yes, it sounds a bit unpleasant to say. I think it’s because they don’t have a lot of knowledge about it themselves. Often, it’s also about that aspect of giftedness.

This was followed by “Lack of Willingness”, with one school leader mentioning: “But it is difficult, in any case, to get the parent council properly filled.”. The barrier “Lack of Alignment” was the third most frequently mentioned, with one school leader illustrating:

And ultimately, it leads to a result, and in the long term, that’s a diploma, which is ultimately what you want as a school, of course. When parents are completely on a different page, then it becomes really difficult for such a child. So, when we as a school and parents are not on the same page, it can sometimes really cause a hassle.

When focusing on barriers to teachers’ involvement, “Lack of Knowledge(sharing)” was the most frequently mentioned, as exemplified by one school leader: “… have too little knowledge of it, despite us organising various training sessions, simply the lack of sufficient knowledge.”. The second most frequently mentioned barrier was “Lack of Willingness”, highlighted by one school leader: “… you have a group that still thinks it’s all nonsense, …”. “Student-Centredness” was third most frequently mentioned, with one school leader stating:

But what I would really appreciate is if teachers are so involved that they say, ‘Yes, even though I do have the regular group, right? Often, you tend to focus on the mean level of your class, so to speak. I have them in mind, but I also try to keep an eye out and sometimes ask a probing question because that triggers them, yes’.

When asked to identify barriers to other school leaders’ involvement, “Lack of Collaboration” was most frequently mentioned. One school leader mentioned:

Yeah, I think it’s really beneficial to compare policies together. Like, ‘Hey, how do you view gifted students? What’s your vision on that, and here’s ours?’ Putting them side by side, right? It might create some friction sometimes. But, well, that can lead to great conversations, I think, and you can use that. However, it’s not like I’ll just take your policy and implement it here. That doesn’t work.

This was followed by “Lack of Willingness”, as illustrated by one school leader: “Yes, I hear from the giftedness specialists who also work at my school that they find it difficult to get some teams on board.”. The third most frequently mentioned barrier was “Lack of Policy”, as exemplified by this quote: “There are a lot of policy plans in schools, often, right? The support plan. I would like to see the school leadership ensure that every support plan also includes a chapter dedicated to gifted students.”.

4.4. Interactions and Satisfaction with Interactions

4.4.1. Interactions Concerning Knowledge Sharing

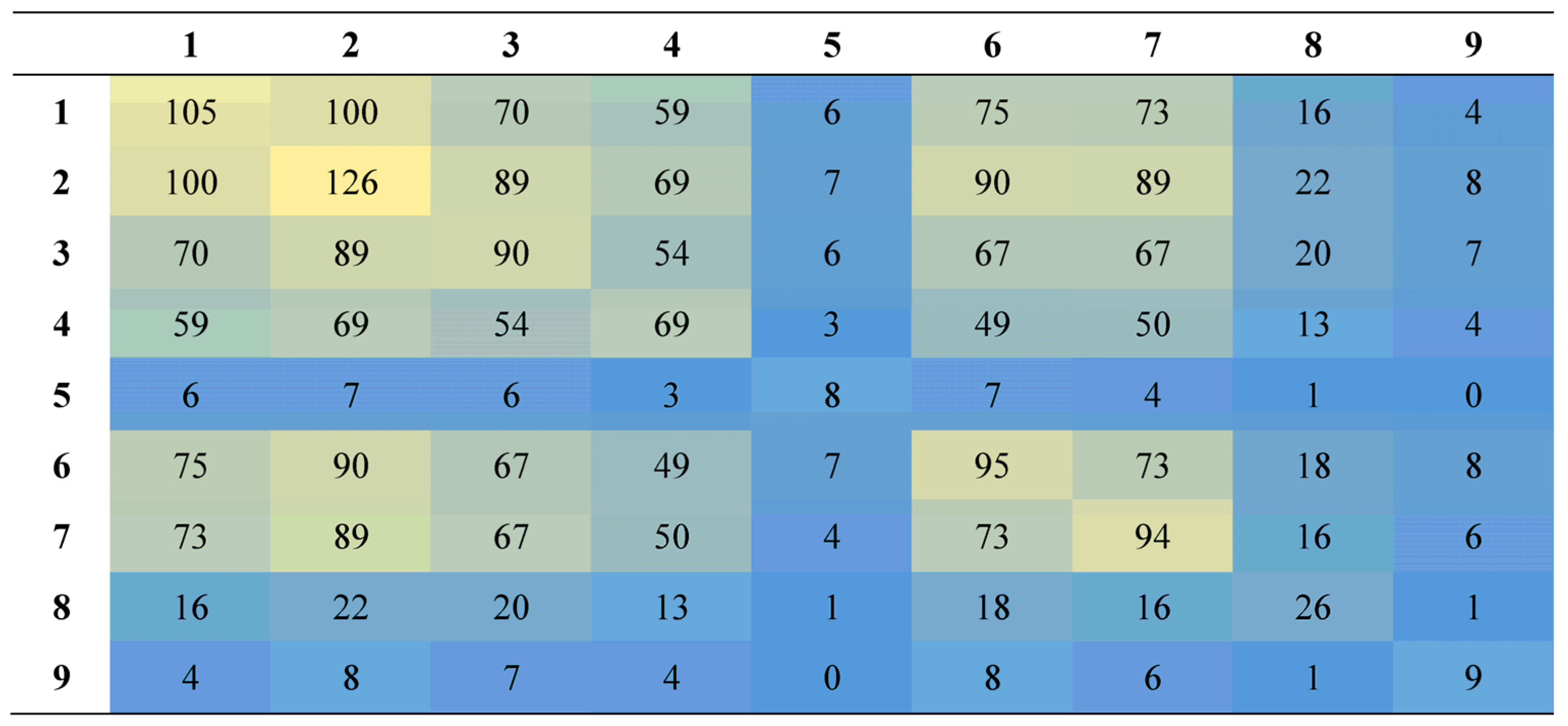

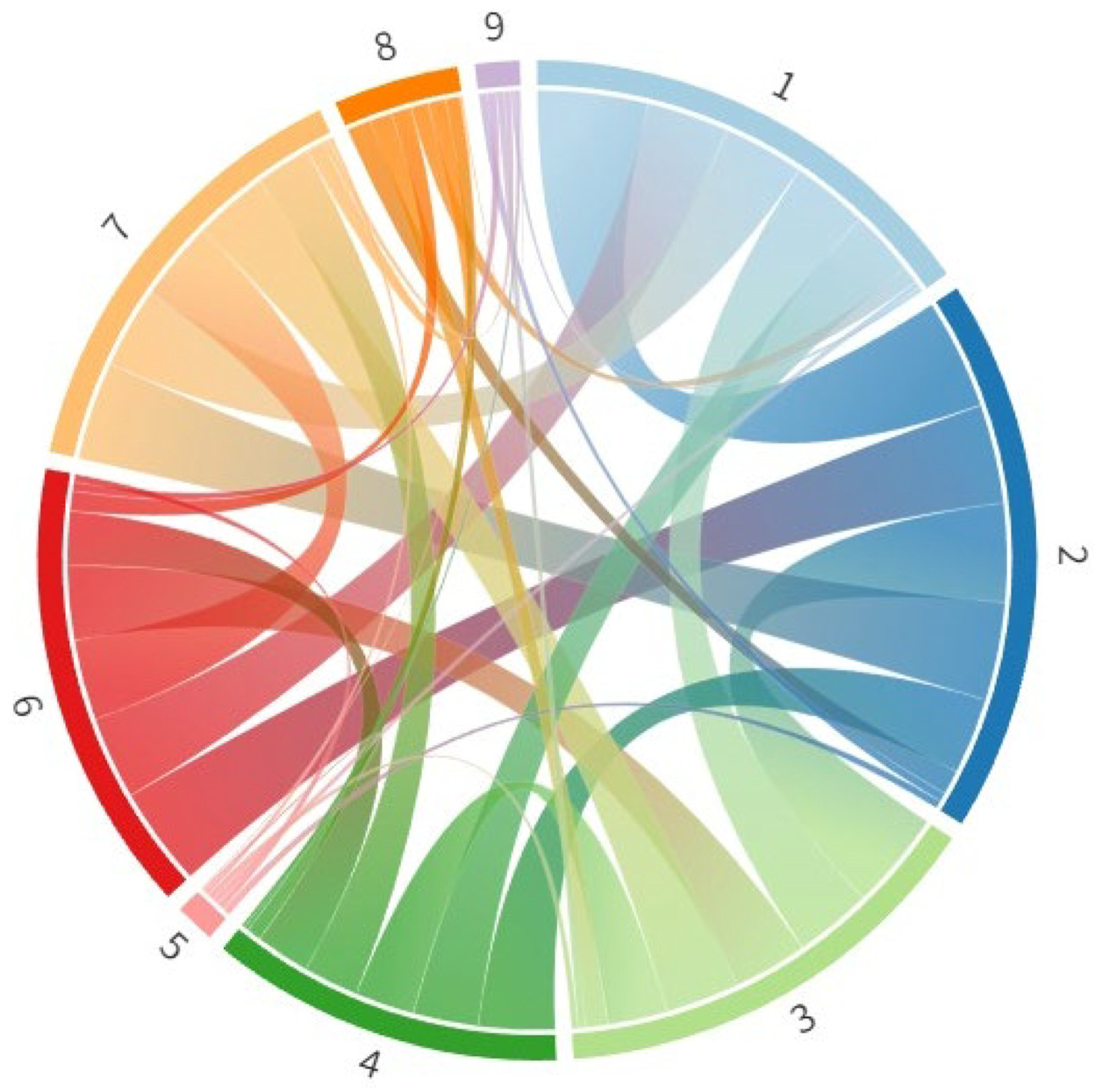

Table 6 provides the descriptive statistics illustrating the frequency of interactions between school leaders and parents, teachers, and other school leaders concerning knowledge sharing on gifted education (RQ4). The mean scores suggest that interactions with parents and other school leaders occurred “yearly” to “multiple times a year”, and interactions with teachers ranged from “multiple times a year” to “monthly”.

Results from repeated measures ANOVA tests unveiled that the effect of actor group was significant F(2, 236) = 30.20, p < 0.001, with a large effect size, partial η2 = 0.204. Simple contrasts revealed that school leaders reported significantly higher levels of interactions regarding knowledge sharing on giftedness with teachers compared to both parents (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.209) and other school leaders (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.299). No differences were found in the frequency of interactions with parents compared to those with other school leaders (p = 0.020). Sphericity was confirmed (Mauchly’s test; p = 0.250).

4.4.2. Interactions Concerning General Support Gifted Students

Table 6 presents the descriptive statistics detailing the frequency of interactions between school leaders and parents, teachers, and other school leaders concerning general support for gifted students at a group level. The mean scores reflect interactions ranging from “yearly” to “multiple times a year” with parents and other school leaders, and from “multiple times a year” to “monthly” with teachers.

Results from repeated measures ANOVA tests showed a significant effect of actor group, F(1.86, 225.41) = 50.60, p < 0.001, with a large effect size, partial η2 = 0.295. Simple contrasts indicated that school leaders had significantly more interactions regarding the general support of gifted students with teachers compared to both parents (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.344) and other school leaders (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.404). Furthermore, interactions with parents were significantly more frequent than those with other school leaders (p = 0.003, η2 = 0.069). Due to a violation of sphericity (Mauchly’s test; p = 0.004), the Huynh-Feldt correction was applied (Epsilon > 0.75).

4.4.3. Interactions Concerning Support Individual Gifted Students

Table 6 displays the descriptive statistics detailing how frequently school leaders interacted with parents, teachers, and other school leaders regarding support for individual gifted students. The mean scores suggest that interactions with parents and other school leaders occurred “yearly” to “multiple times a year”, and interactions with teachers ranged from “multiple times a year” to “monthly”.

Results from repeated measures ANOVA tests revealed a significant effect of the actor group, F(2, 240) = 67.93, p < 0.001, with a large effect size, partial η2 = 0.361. Simple contrasts indicated that school leaders reported significantly more frequent interactions with teachers regarding individual support for gifted students compared to both parents (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.336) and other school leaders (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.482). Additionally, interactions with parents were significantly more frequent than those with other school leaders (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.134). Sphericity was confirmed (Mauchly’s test; p = 0.128).

4.4.4. Interactions Concerning Education-Related Issues

Table 6 presents the descriptive statistics detailing the frequency of interactions school 6leaders had with parents, teachers, and other school leaders concerning education-related issues. These scores indicated a mean score of “multiple times a year” for interactions with parents and other school leaders, and a mean ranging from “monthly” to “weekly” for interactions with teachers.

Results from repeated measures ANOVA tests showed a significant effect of actor group, F(2, 250) = 85.37, p < 0.001, with a large effect size, partial η2 = 0.406. Simple contrasts revealed that school leaders interacted significantly more frequently with teachers about education-related issues compared to both parents (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.534) and other school leaders (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.469). No significant difference was found in the frequency of interactions with parents and other school leaders (p = 0.894). Sphericity was assumed (Mauchly’s test; p = 0.143).

4.4.5. Satisfaction with Interactions

To further address RQ4,

Table 7 presents the descriptive statistics outlining the level of school leaders’ satisfaction with their interactions with parents, teachers, and other school leaders regarding gifted education. The results show a mean score ranging from “neutral” to “satisfied” for all actor groups.

Results from repeated measures ANOVA tests revealed that the effect of actor group was not significant, F(1.84, 207.92) = 1.97, p = 0.146. Therefore, there were no significant differences in school leaders’ satisfaction levels in their interactions with parents, teachers, and other school leaders. Due to a violation of sphericity (Mauchly’s test; p = 0.002), the Huynh-Feldt correction was applied (Epsilon > 0.75).

4.5. Relationship Between Type of Interactions and Satisfaction with Interactions

To address RQ5, simple linear regression analyses were conducted, revealing significant relationships between the frequency of interactions and corresponding satisfaction levels of school leaders in gifted education, across all types of interactions with teachers and other school leaders.

Table 8 presented the varied observed effect sizes. Interactions between school leaders and parents showed a significant relationship only when discussing support for gifted students in general. The findings underscore that more frequent interactions with actors correlate with higher satisfaction levels among school leaders in gifted education.

4.6. Facilitators and Barriers to Interactions

4.6.1. Facilitators to Interactions

Interview participants were asked to identify factors facilitating the interactions with the various actor groups, i.e., parents, teachers, and other school leaders (RQ6). These facilitators are detailed in

Table 9, alongside descriptive statistics. Quotes representing each facilitator are presented in

Supplemental Table S3. The following results focus on the three most frequently mentioned facilitators.

For interactions with parents, the most frequently mentioned facilitator was “Open Communication”, with one school leader commenting:

It doesn’t matter what the conversation is about. You just need to make sure you listen to each other, because when you’re angry, you don’t listen to each other well anymore. Then you only think your own opinion is important.

This was followed by “Approachability”, illustrated by one school leader:

Well, as I mentioned earlier, having that conversation with the parent really made a difference. It led to the same parent calling me a while back. ‘Hey [Name of school leader], could you do this and that for me?’ I’ve never had that kind of outreach from that parent before, so I can see that reaching out has made it easier for them to reconnect with me.

The third most frequently mentioned was “Trust”. One school leader mentioned:

Trusting in each other’s abilities is crucial to ensure things go well, so having genuine confidence that parents are professionals who know what their child needs, and likewise, that parents have trust in the school to do the right things together and keep the child at the centre, that’s really the reason for success.

When focusing on facilitators to the interaction with teachers, school leaders most frequently mentioned “Willingness”, as expressed by one school leader: “… the other colleague who just goes full throttle right away and makes everything that seemed impossible possible, right? That’s just great.”. This was followed by “Open Communication”, as underscored by one school leader who mentioned: “Yes, it’s always pleasant when it’s an open conversation with room for reflection.”. Lastly, the third most frequently mentioned facilitator was “Approachability”, as exemplified by one school leader:

They always say, “I can always drop by your office.” Yes, that’s how I am, you can drop by anytime. […] And that means they also want to discuss and can discuss not just about gifted education, but about various other things as well.

Concerning interactions with other school leaders, “Willingness” was the most frequently mentioned facilitator. One school leader described:

Time is always a problem, but when you’re dealing with something, you find the time to solve it. So, I notice that colleagues are always willing to be there for each other, to help or give advice. Similarly, if someone asks me something, I do the same, so it goes both ways.

The second most frequently mentioned facilitator was “Approachability”. One school leader expressed: “As colleagues, being part of a fairly small school board, we have short lines of communication. It’s easy to pick up the phone and quickly ask each other something, so there’s good cooperation in that sense.”. The third most frequently mentioned facilitator was “Open Communication”, illustrated by this quote: “Yes, being able to have an open discussion, not having to agree with each other, and putting differences on the table is something I find very pleasant and constructive to work with.”.

4.6.2. Barriers to Interactions

To further address RQ6, participating school leaders were asked to identify barriers to the interactions with the different actor groups. These barriers, including descriptive statistics, are detailed in

Table 10. Quotes representing each barrier are presented in

Supplemental Table S4. The following results focused on the three most frequently mentioned barriers.

The most frequently mentioned barrier by school leaders concerning interactions with parents was “Lack of Open Communication”, as one school leader illustrated by saying: “It doesn’t matter what the conversation is about. As long as you ensure that you listen to each other, because when you’re angry, you don’t listen well to each other, so you only consider your own opinion important.”. This was followed by “Lack of Willingness”, one school leader stated: “Yes. Let me think. Yes, I think that certain assumptions, judgments, and yes, parents who have already filled in things. Or from school as well, from both sides, that communication really gets in the way.”. The third most frequently mentioned was “Lack of Trust”, exemplified by one school leader stating: “Yes, when a parent has no or only partial trust in the school, it impacts the child.”.

When focusing on interacting with teachers, school leaders most frequently mentioned the barrier “Time-Work Pressure”. One school leader mentioned: “The reason it’s less effective is usually due to two main reasons: either the workload, meaning you’re asking colleagues to do things they really don’t have time for, yet you still want them to do it.”. The second most frequently mentioned barrier was “Lack of Knowledge(sharing)”, with one school leader saying:

I always think it’s good to have conversations about education, regardless of the topic. And with gifted education, you do notice that there is still a lot of unknowns, which sometimes leads to viewpoints or opinions that are not entirely in favour of the gifted child.

“Lack of Willingness” was the third most frequently mentioned barrier, illustrated by this quote: “And on the other hand, there’s still the colleague who has less attention and interest in these students or this type of student. That can make things a bit more difficult, yes.”.

Concerning interactions with other school leaders, “Lack of Willingness” was most often perceived as a barrier. One school leader stated: “Sometimes schools are quite cautious among themselves, you know? Because there’s also a PR aspect at play in these situations.”. This was followed by “Time-Work Pressure”, as exemplified by one school leader stating: “I just haven’t had much time for that this year, so it’s also a bit of that.”. “Lack of Policy” was the third most frequently mentioned barrier, with one school leader mentioning: “I would like it to be more structured.”.

4.7. Relationship Between Satisfaction with Involvement and Satisfaction with Interactions

To address RQ7, simple linear regression analyses were conducted, revealing significant relationships between school leaders’ satisfaction levels with perceived involvement and their satisfaction levels with interactions in gifted education across all actor groups. These relationships were found to have medium to large effect sizes, as detailed in

Table 11. This indicates that higher satisfaction with perceived involvement of an actor correlates with greater satisfaction with their interactions among school leaders in gifted education.

4.8. Perceived Relationship Between Satisfaction with Involvement and Interaction

Interview participants were asked about their perceived relationships regarding their satisfaction with actor involvement and their interactions, thereby addressing the final research question, RQ8. These perceived relationships, along with descriptive statistics, are outlined in

Table 12.

Supplemental Table S5 presents example quotes per perceived relationship. The following results focused on the three most frequently mentioned relationships.

When focusing on the relationship between satisfaction with parental involvement, and the interaction school leaders had with them, “Not Perceived” was mentioned most often. This is illustrated by a school leader mentioning: “I don’t think the influence on that affects the frequency or quality, no.”. This was followed by “More Satisfied–Better Interaction”. One school leader mentioned: “If all goes well, I will have informal contact with parents much faster and easier. And if communication is difficult, I am less likely to speak to someone quickly and easily in a fun, informal way.”

The third most frequently mentioned relationship was “More Satisfied–More Interaction”, with one school leader stating: “Yes, because if parents seek you out, it is naturally much easier.”.

School leaders mentioned “Less Satisfied–More Interaction” most frequently when focusing on the relationship between their satisfaction with the perceived involvement of teachers and the interactions these school leaders had with the teachers, with one school leader saying: “Yes, because when things aren’t going well, you have more frequent interactions about it. And you have more to deal with.”. This was followed by “Not Perceived”, highlighted by one school leader stating: “I cannot say that, no.”. Lastly, “More Satisfied–Better Interaction” was the third most frequently mentioned relationship, with one school leader mentioning: “Yes, of course. So, the moment you have satisfaction and a good feeling about it, you get more done, as I mentioned earlier. That seems logical to me, yes.”.

When exploring the relationship between satisfaction with other school leaders’ involvement, and the interactions school leaders had with them, “Not Perceived” was mentioned most often. One school leader exemplified: “That I couldn’t say.”. This was followed by “More Satisfied–More Interaction”, with one school leader stating:

And if you want to initiate new developments or set up something completely new, then yes, you just need a lot more help. You have a lot more questions, and then you also seek much more contact, and that opportunity is just there, so I’m very satisfied with that.

All other mentioned relationships only occurred once.

5. Discussion

This exploratory mixed-methods study, using both a questionnaire and semi-structured interviews, examined school leaders’ perceptions of the involvement of and interactions with parents, teachers, and other school leaders in gifted education. In doing so, the current study aimed to provide valuable insights into previously unknown perspectives, thereby enhancing the understanding of inclusive primary and secondary education for gifted students.

5.1. Involvement Concerning Education for Gifted Students

The questionnaire data revealed that school leaders perceived varying levels of involvement among different actor groups (RQ1). Teachers were considered as most involved, while parents and other school leaders were perceived as less involved. This can be logically explained by the fact that there are varying contexts and relational dynamics among the actor groups. For example, teachers naturally have more frequent opportunities for involving with the school leader, due to their daily presence and direct interaction with the school leader. In contrast, parents are typically external actors with fewer built-in opportunities for direct involvement with the school leader. Similarly, other school leaders operate in other schools, which limits their day-to-day involvement with other school leaders. Furthermore, in the Netherlands, school leaders operate with such autonomy that contact with other school leaders from other schools is not necessary for leading the school (

Neeleman, 2019).

Despite these variations in perceived involvement, school leaders’ overall satisfaction with the involvement of parents, teachers, and other school leaders in gifted education remained neutral to satisfied, with no significant differences between actor groups. This suggests that varying levels of involvement do not lead to dissatisfaction, but may rather reflect a functional balance in collaboration within the gifted education context. This supports the idea that collaboration between educators, administrators (such as school leaders), and parents is essential for effecting change in gifted education (

VanTassel-Baska & Johnsen, 2007).

Paccaud et al. (

2021) emphasised that families and schools are two essential stakeholders in the development and educational success of students.

Erdener and Knoeppel (

2018) also highlighted that the synergy between families, teachers, and the community is key to improving student development and communication. The positive relationship between perceived involvement and satisfaction with involvement (RQ2) reinforces the idea that, in general, more involvement results in higher satisfaction. Despite the varying levels of involvement across actor groups, the overall satisfaction of school leaders again suggests a functional balance in roles, where each actor group contributes to gifted education. This functional balance and the perceived relationships also align with the actiotope model’s idea that successful talent development depends on interactions between key actors in a student’s environment, such as parents, teachers, and school leaders (

Ziegler, 2005;

Ziegler & Phillipson, 2012). Thus, the perceived involvement levels of parents, teachers, and other school leaders can be seen as part of a broader system in which all actors play complementary roles in supporting gifted students’ development.

Interviews with school leaders revealed that willingness to contribute to and/or communicate about gifted education is a facilitator for the involvement of parents, teachers, and other school leaders, while absence of this willingness was seen as a barrier (RQ3). This finding aligns with

Erdener (

2014), who reported that teachers’ willingness in interactions positively impact parental involvement. In the current study, school leaders similarly identified willingness as an essential factor in facilitating involvement of all actor groups. For the involvement of teachers, student-centredness and knowledge(sharing) were mentioned as facilitators by the school leaders, whereas collaboration, willingness, and policy were significant facilitators for involvement of other school leaders, with the absence of these factors noted as barriers. This is consistent with conclusions drawn by

Jones and Harris (

2014), who emphasised the role of professional collaboration in driving organisational change. The school leaders in the current study underscored the importance of such collaboration within gifted education.

5.2. Interactions Concerning Education for Gifted Students

The current study also examined school leaders’ interactions with parents, teachers, and other school leaders in the context of gifted education (RQ4), as the understanding of these dynamics could be fundamental for enhancing support for gifted students. Questionnaire data revealed that interactions with teachers occurred more frequently than with parents and other school leaders across all queried topics (i.e., knowledge sharing, general support for gifted students, support for individual gifted students, and education-related issues). However, this frequency did not significantly impact satisfaction levels of school leaders. Satisfaction remained neutral to satisfied, suggesting that the nature and quality of these interactions are more crucial than their frequency.

A positive relationship was found between the perceived number of interactions that school leaders had with other actors and their corresponding satisfaction, particularly with teachers and other school leaders. For interactions with parents, this positive relationship was found only for interactions related to general support for gifted students. These findings suggests that while the

quantity of interactions can affect satisfaction, it is likely that the

quality of these interactions ultimately enhances both satisfaction and outcomes (RQ5). This is consistent with earlier research by

Hung and Lin (

2013), which, though conducted in a non-educational setting, emphasised the role of effective communication in influencing satisfaction. Similarly,

Paccaud et al. (

2021) highlighted the importance of quality communication in the context of school-family relationships, reinforcing the need to focus on improving interaction quality to achieve higher satisfaction levels.

The interviews identified school leaders’ perceived key facilitators and barriers related to their interactions with parents, teachers, and other school leaders (RQ6). Considering interactions with parents, open communication and trust were mentioned as important facilitators, while the absence of these factors was noted as significant. This aligns with the findings of

Paccaud et al. (

2021), who emphasised the importance of trust and effective communication in fostering school–family collaboration. For interactions with teachers and other school leaders, willingness to contribute to and/or communicate about gifted education was frequently noted as a facilitator, while its absence was commonly seen as a barrier. As previously noted by

Erdener (

2014), willingness is essential in ensuring productive interactions and positive student outcomes.

The current study contributes to the actiotope model of giftedness that emphasises the interaction of systems surrounding the gifted students as critical to their talent development (

Ziegler & Stoeger, 2017). This model views giftedness as a result of complex interactions between, for instance, environmental systems. From the current study, it can be concluded that open communication, approachability, trust, willingness, collaboration and alignment are key factors in interactions between school leaders and parents, teachers, and other school leaders that positively contribute to talent development. This empirically based knowledge is a significant addition to this theoretical model.

5.3. Relationship Between Involvement and Interaction Concerning Education for Gifted Students

Questionnaire data revealed that school leaders’ satisfaction with the involvement of any actor group was positively related to their satisfaction with interactions with those groups (RQ7). However, interviews suggested that the majority of school leaders did not perceive a direct relationship between these factors (RQ8). When school leaders did perceive a relationship, they indicated that higher satisfaction with involvement generally led to better interactions with parents and teachers, and to more frequent interactions with parents and other school leaders. Altogether, these findings underscore the complexity of the relationship between involvement and interactions. Previous sections of this discussion highlighted school leaders’ perceived importance of the involvement of and interactions with parents, teachers, and school leaders. Therefore, it can be assumed that the balance between frequency and quality favours a functional balance, where quality of interactions and adequate involvement create a supportive environment for talent development. This, in turn, aligns to the actiotope model, which emphasised the complexity of interactions between (environmental) systems surrounding the gifted student, ultimately enhancing their development (

Ziegler, 2005;

Ziegler & Phillipson, 2012;

Ziegler & Stoeger, 2017).

The current study provides important insights into the mechanisms that could contribute to effective systems for talent development. Several overlaps were observed between the most frequently mentioned facilitators and barriers to involvement and interactions. For example, for parents, teachers and other school leaders, willingness was a facilitator, while the absence of willingness was frequently mentioned as barrier to both involvement and interaction. These overlaps between facilitators and barriers suggest that small changes in the system, such as enhancing willingness or improving communication, hold the potential to have a substantial positive impact on the overall involvement of actors in gifted education. This is again aligned with the actiotope model, indicating that improvements in the interaction within the environmental systems could potentially enhance the development of a gifted student (

Ziegler & Stoeger, 2017).

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

The current study had some limitations, resulting in recommendations for future research. Firstly, the focus was exclusively on school leaders’ perspectives, which does not capture all perspectives and the full scope of involvement of and interactions with various actors in gifted education. Expanding research to include perspectives from other key actors, such as parents, teachers, and students, could provide a more comprehensive view.

Wai and Guilbault (

2023) highlighted the value of integrating multidisciplinary perspectives in gifted education research, suggesting that insights from diverse fields can help address complex questions and broaden understanding. By incorporating perspectives beyond gifted education professionals into research, new ideas and insights could be uncovered, ultimately enriching the overall knowledge and research in this area.

Secondly, the current study may have been affected by participation bias, which is common in questionnaire research and can lead to a skewed dataset (

Elston, 2021). Although reminder strategies were used, which have been shown to reduce bias (

Verger et al., 2021), these efforts did not result in a sufficient number of interview participants. The additional recruitment efforts could have further contributed to participant selection bias. It is likely that school leaders with a particular interest in or affinity for giftedness were more inclined to participate in this study.

Thirdly, the current study included school leaders from Dutch schools for primary and secondary education facilitating a broader understanding of shared principles and overarching patterns concerning concepts of (satisfaction with) involvement and interaction with actors. However, results might vary between the two types of education, because of differences in the way the actor groups behaviour in both types. Unfortunately, our limited sample size prevented us from making a comparison between the two education types. Therefore, exploring differences between primary and secondary education could offer valuable insights. It could also be relevant to investigate whether there is a relationship between the number and combination of offered interventions for gifted students and the level of education (i.e., primary and secondary).

Additionally, comparing perspectives of school leaders from schools that provide gifted education to those of schools that do not, might help develop a more comprehensive view of involvement and interactions across educational settings. In the Netherlands, schools operate with significant autonomy, making school leaders crucial decision-makers who oversee school processes (

Neeleman, 2019). Finally, this research needs to be expanded to other countries and cultures to provide further insights in cross-cultural differences and similarities which could lead to a deeper understanding of gifted education (

VanTassel-Baska, 2013).

5.5. Implications for Educational Practice

The current study has several implications for educational practice, highlighting several key areas where professional development can be enhanced to better support gifted education. These implications are grounded in the perceptions and experiences of school leaders, as well as the identified facilitators and barriers to effective involvement and interaction with parents, teachers, and other school leaders.

School leaders, parents, and teachers are advised to foster a willingness to contribute to and/or communicate about gifted education. This collective willingness among parents, teachers, and school leaders could be essential for overcoming barriers and enhancing support for gifted students. Parents are encouraged to remain approachable, and engage in open communication regarding their gifted child’s education. Teachers are advised to actively update their knowledge about giftedness and to share it with their colleagues and other actors. School leaders are advised to refine and clarify their policies on gifted education.

The current study offers an overview of school leaders’ perceptions regarding the involvement of and interactions with key actors in gifted education, including facilitators and barriers. By highlighting these factors, it creates awareness that serves as an initial step toward improvement. Recognising these dynamics enables school leaders and other actors to address existing gaps and challenges actively. This understanding can serve as a foundation for developing targeted strategies to enhance collaboration and support for gifted students.

Furthermore, continuous professional development should include opportunities for teachers and school leaders to update and share their knowledge about gifted education. This can be achieved, for example, through workshops, seminars, and collaborative learning communities. Furthermore, by means of continuous professional development, expertise can be built in identifying and supporting gifted students which is crucial for creating a challenging and supportive learning environment (

Steenberghs et al., 2023). Additionally, professional development could emphasise the importance of a student-centred approach in gifted education. This involves recognising and addressing the unique needs of gifted students and ensuring that educational practices are tailored to support their development (

Ninkov, 2020). Training in student-centred teaching methods can help teachers create a more inclusive and supportive classroom environment.

Professional development could also address possible barriers to involvement and interaction identified in the current study. Providing strategies to enhance positive involvement and interaction of all actors can lead towards more effective support for gifted students. For example, professional development programmes could focus on enhancing collaboration and communication skills among school leaders, teachers, and parents, because effective communication is essential for establishing strong partnerships and preventing misunderstandings (

Herweijer & Vogels, 2013). Training in open communication and trust-building can facilitate better interactions and involvement (

Paccaud et al., 2021).

Concerning the school level, it is important that school leaders endorse the importance of tailored and inclusive education for gifted students. Creating a supportive school culture that values and promotes gifted education is essential (

Gubbels et al., 2025). Professional development programmes could include principles on how to foster a positive school culture, where all stakeholders are committed to supporting gifted students (

Haworth, 2020). This includes promoting a shared vision and values among school leaders, teachers, and parents. In order to do so, school leaders could be invited to attend professional development activities concerning development and implementation of clear policies that support gifted education, such as the systemic approach to inclusive education and the actiotope model of giftedness (

Ziegler & Stoeger, 2017). Clear policies can guide teachers in implementing effective educational interventions (

Subotnik et al., 2011).

By focusing on these areas, professional development programmes can better equip school leaders, teachers, and parents to support the educational needs of gifted students, ultimately leading to more effective and inclusive educational practices.