1. Introduction

The aim of the study was to support young students’ learning of social skills through playful learning activities, based on a solution-based psychological approach. In this section, we introduce the context of our study and the theoretical basis of fostering students’ social skills. Additionally, we review the literature on the solution-focused approach and playful learning pedagogy, assessing their relevance and potential benefits applied in an educational context. Finally, we explain the purpose of this study and outline the research questions that guided our investigation.

1.1. Social Skills for Students’ Development

Social skills are essential for fostering healthy relationships, promoting positive social interactions, and ensuring the individual’s ability to develop meaningful relationships and actively participate within the community (

Cacioppo, 2002). Supporting the development of these skills in students is increasingly recognized as crucial in educational contexts, given their profound impact on holistic growth and social interaction across diverse social environments. Social skills are defined as “the requisite abilities needed to perform competently in social situations” (

Grover et al., 2020, p. 19). These include behaviors such as communication, emotional regulation, and cooperation, which underpin adherence to societal norms, support mental health, and promote overall well-being (

Beauchamp & Anderson, 2010).

Social skills encompass three key components: attention–executive component; communication component; and social–emotional component (

Beauchamp & Anderson, 2010). The attention–executive component involves attentional control, self-regulation, cognitive flexibility, and goal setting, all of which are critical for managing social interactions. Attentional control, for instance, enables behaviors like waiting for one’s turn during a game, helping foster positive peer responses (

Anderson, 2008). Communication forms the foundation of social interactions, allowing the exchange of thoughts, intentions, and information. Key aspects include expressive and receptive language skills, joint attention, and the integration of affect and gesture (

Beauchamp & Anderson, 2010;

Landa, 2005). Despite its importance, aspects of social communication have often been overlooked in the literature even though they are directly linked to peer acceptance and successful relationship-building (

Landa, 2005). The social–emotional component includes emotional understanding and regulation, vital for empathy, conflict resolution, and fostering interpersonal connections. These skills enable individuals to navigate complex social environments effectively (

Grover et al., 2020).

Social skills are frequently assessed using standardized measures, such as the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS) (

Gresham & Elliott, 2008), which evaluates domains like communication, cooperation, empathy, and self-control. Definitions of social skills, while varied, consistently emphasize the importance of social communication and interaction within specific contexts (

Little et al., 2017). The SSIS identifies key areas of development, including communication, cooperation, assertion, responsibility, empathy, engagement, and self-control, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding and supporting these abilities (

Grover et al., 2020).

The development of social skills is a central concern for educators and parents as these skills directly influence peer relationships and long-term social integration. This study aims to investigate the use of the “Curious About Others” play, grounded in solution-focused and playful pedagogical approaches, in supporting students’ learning of social skills. Specifically, the educational play activity is designed to address the three key components of social skills—attention–executive, communication, and social–emotional —to foster abilities in communication, cooperation, empathy, and self-control. Such interventions highlight the potential for structured, engaging activities to foster students’ social skills.

1.2. Solution-Focused Approach (SFA) in “Curious About Others” Play

This study was designed to help students acquire social skills and build positive relationships between students through the “Curious about Others” educational guided social play. Developed by Dr. Ben Furman and his colleagues based on an SFA (

Furman, 2024), the aim of this activity is to teach students how to express interest in others positively and to understand that building a positive connection starts by showing genuine interest in others. Human beings naturally gravitate toward those who show interest in them. When individuals feel acknowledged, liked, or admired, they become happier and more open, fostering mutual and reciprocal positive feelings. This is a fundamental way to build rapport and connect with people.

This play “Curious about Others” integrated several key psychological and educational theories, including the SFA, playful learning and engagement, Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, psychological safety, active learning, and collaborative learning. The following sections will explore how these theories and approaches are applied in the design of this educational guided social play.

Solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) was originally developed in the field of psychotherapy, but in recent years, it has been increasingly applied and practiced in the educational field (

Ajmal, 2001;

Milner & Bateman, 2011;

Redpath & Harper, 1999;

Rhodes, 1993;

Stobie et al., 2005;

Walsh, 2012). SFBT was first developed by Insoo Kim Berg and Steve de Shazer in the 1980s (

DeJong & Berg, 2002;

De Shazer, 1985,

1988). SFBT is centered around the concept of envisioning desired future outcomes and identifying the strengths and resources needed to achieve those outcomes (

George et al., 1999). It emphasizes the establishment of supportive relationships in which communication and interaction are focused on the positive strengths, resources, and capabilities of individuals (

DeJong & Berg, 2002).

Several researchers have delineated the core principles of SFBT, which include a focus on preferred behaviors and individual strengths (

Quick, 2008;

Lipchik, 2011;

Nicholas, 2014;

Sklare et al., 2003). SFBT has gained acceptance as an evidence-based psychological therapy intervention (

Alexander & Sked, 2010;

Cepukiene & Pakrosnis, 2011). During the past few decades, an SFA, based on the main principle of SFBT focusing on the students’ strengths and developing new positive behaviors, has been widely used and applied in the educational field to support students’ learning and well-being by educators, notably by teachers, school psychologists, and school counselors (

Kim & Kelly, 2008;

Kim & Franklin, 2009;

Murphy, 2008;

Sklare, 2005).

Kim and Kelly (

2008) have stated that the advantages of the SFA in a school setting are its strengths-based approach, student-centered approach, and actions in which small changes matter. Educators, including teachers, school psychologists, and counselors, have widely adopted the SFA to support students’ academic and emotional development (

Kim & Kelly, 2008). The primary goals of SFA in schools are to help students focus on their goals, identify their strengths and resources, and engage in small, positive actions that can lead to broader changes in their lives.

Kim and Franklin (

2009) conducted an influential meta-analysis examining SFBT’s effectiveness in schools. They found that SFBT led to positive student outcomes, particularly in addressing internalizing behaviors like anxiety and depression.

Niu et al. (

2022) have demonstrated that an SFA can enhance relationships among students, parents, and teachers. Research indicates that an SFA can be effectively integrated into pedagogical methods to support the development of students’ social–emotional and self-management skills (

Niu & Niemi, 2020;

Niu et al., 2022).

Kim and Franklin’s (

2009) meta-analysis offers a comprehensive evaluation of SFBT in school settings. It demonstrates the SFBT’s effectiveness in fostering positive student outcomes, particularly in reducing internalizing behaviors such as anxiety and depression. Similarly, research by

Niu et al. (

2022) highlights that SFA can improve relationships among students, parents, and teachers, fostering stronger social connections. Integrating an SFA into pedagogical strategies has proven effective in enhancing students’ social–emotional learning and self-management skills (

Niu & Niemi, 2020). Furthermore, in a broader context,

Bond et al. (

2013) conducted an international review of SFBT in educational settings, and confirmed its value, especially for addressing both internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Their study emphasizes SFBT’s strength-based and goal-oriented framework, which is well suited for school environments.

This study introduces the “Curious About Others” educational play, a practical tool based on the SFA designed to enhance social skills and improve relationship dynamics among students. By focusing on students’ hobbies, strengths, and talents, the play aims to foster positive interactions and build closer connections among students. During the explanation and demonstration of the play, teachers provide examples of solution-focused questions to ask, emphasizing the importance of positive inquiries while advising against questions that could elicit negative feelings.

1.3. Psychological Safety in Learning of Social Skills

Psychological safety, as conceptualized by

Edmondson (

1999), has emerged as a crucial factor influencing team learning dynamics.

Carmeli and Gittell (

2009) investigated the interplay between psychological safety, high-quality interpersonal relationships, and organizational learning. Their findings underscored a positive correlation between robust interpersonal relationships and psychological safety, which, in turn, fostered enhanced learning behaviors within organizational contexts (

Carmeli & Gittell, 2009). Furthermore, research (

Roh et al., 2018) suggested that pre-briefing strategies, such as orientation sessions conducted by instructors, could enhance team psychological safety and performance among students.

In the “Curious about Others” play, the promotion of psychological safety can be approached through several strategies: First, participants affirm each other’s contributions by responding positively when hobbies are shared, using gestures or words like “I also like it” or “you are great!”. Second, students are encouraged to use SFA questions that stimulate positive emotions and cognitive engagement. If unsure about what to ask, students can defer their turn to the next person by saying “Pass the question”. Third, participants are given the option to decline to answer a question they feel uncomfortable with, by saying “Pass, next question please”. Fourth, a “talking pen” can be used to ensure equitable expression opportunities for each participant, enhancing overall inclusivity and psychological safety within the group environment.

1.4. Playful Learning, Active and Collaborative Learning in the “Curious About Others” Play

The “Curious About Others” play incorporates playful learning and active and collaborative learning approaches, positioning students as active participants in group activities in their own educational journeys.

Play has been recognized as a powerful tool to inform, engage, and influence attitudes and behaviors (

Whitton, 2018). Playful learning brings the elements of fun, interest, and engagement in learning, and it can attract and retain the learners in their learning process. Research (

Andreopoulou & Moustakas, 2019) indicates that playful learning can support the development of interpersonal competencies and social skills, which are crucial for students.

Playful learning can be an effective mode of teaching and learning, and it generates excitement, enjoyment, and interest, enhancing motivation and engagement (

Rice, 2009). The research on playful learning indicates that it positively impacts learning at a range of school levels, as well as in professional environments (

Sawyer, 2006). Integrating play with learning can be challenging for teachers (

Hyvönen, 2011).

Vogt and Schiemann (

2020) suggested that teachers benefit from workshops and interventions through which they can act playfully, learn agency and expertise, and develop their pedagogical strengths. There are various types of play. This study focused on guided social play, a form of play through which adults create an environment with specific learning goals in mind but which allows children to explore and interact freely. This type of play promotes interaction with peers, fostering social skills and relationships. It has also been described as ‘intentional teaching’ (

Epstein, 2007), ‘conceptual play’ (

Fleer, 2008), and ‘pedagogical activity’ (

Dockett, 2010). In this study, teachers used the “Curious About Others” game as a pedagogical intervention to support students in developing their social skills.

Furthermore, this educational play is conducted in groups in which students work together. Collaborative learning, widely advocated for its role in acquiring competencies (

Barkley et al., 2005;

Niu, 2021), fosters interactions between students in the classroom.

Niu’s (

2021) research indicated that a safe, collaborative learning environment, with students as active agents in their learning and teachers as facilitators, is crucial for developing students’ generic competencies.

Sociocultural theory from Vygotsky’s perspective (

Vygotsky, 1978) is also reflected in the “Curious about Others” play, which has features in his thinking in the role of interaction and language. This impacts how people develop their social skills through interactions through the social aspects of the play. Sociocultural theory provides a foundational perspective on the development of social skills, particularly through the lens of play. This theoretical framework underscores the significance of children’s experiences and social interactions in shaping the complexity of their play activities (

Bodrova, 2008;

Hakkarainen, 2006;

Holzman, 2009;

Van Oers, 2010). Central to the sociocultural viewpoint is the role of language as the principal cultural tool for knowledge creation (

Van Oers, 2010). The role of interaction (

Holzman, 2009) is critical for students’ learning; the interactions are not limited only to interaction between human beings but also include interactions between the learners and artifacts, such as the tools used in learning.

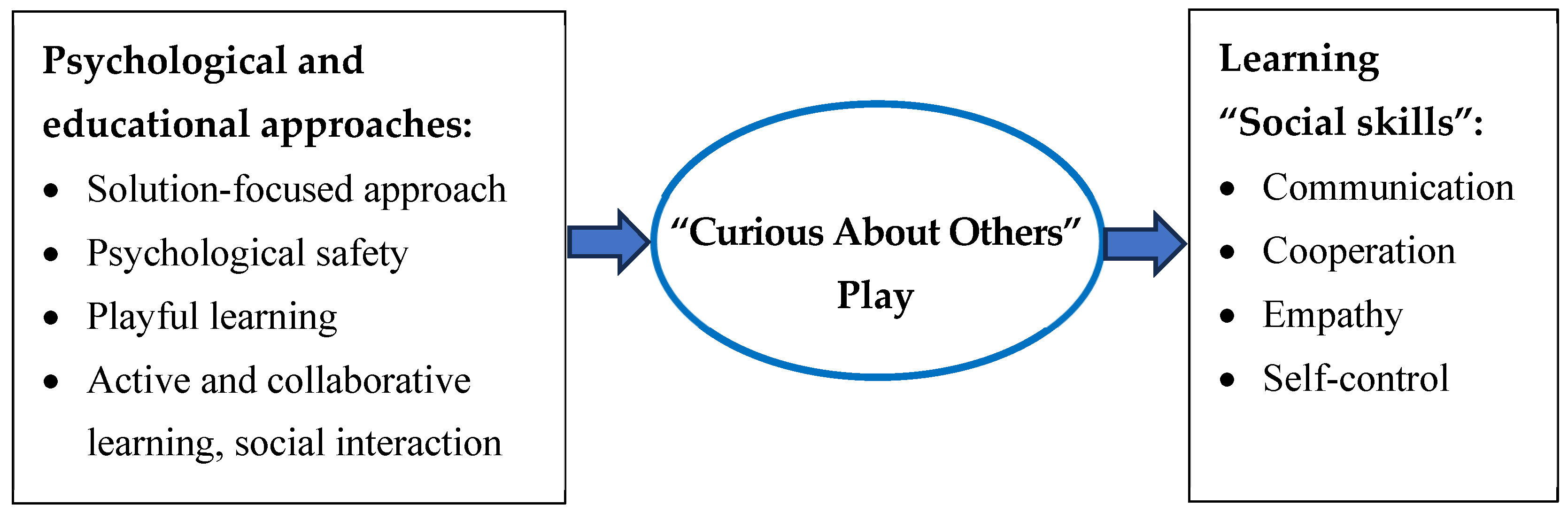

In this study, the “Curious About Others” play was designed to embody these characteristics, integrating cooperative and active learning approaches. Embedded within this approach are elements of the SFA, psychological safety, Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, and playful learning. This integration defined educational objectives aimed at nurturing social skills and enhancing relationship dynamics between students.

1.5. Research Aims, Theoretical Framework, and Research Questions

In our study, we examined how young students’ social skills could be enhanced through playful learning using the “Curious About Others” activity, which integrates several educational and psychological theories and approaches. Our objective was to investigate students’ perceptions of their learning experiences and the development of their social skills through participation in this activity within the school environment. We incorporated key theories and concepts discussed in

Section 1.1,

Section 1.2,

Section 1.3 and

Section 1.4 into the theoretical framework presented in

Figure 1.

In this study, we sought to respond to the following research questions:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): What did students perceive as their learning outcomes related to social skills from the activity?

Research Question 2 (RQ2): What challenges did students encounter during the activity, and how did they address these obstacles?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

This study was conducted as one part of a school project that was aimed at enhancing students’ development and well-being in a primary school located in Beijing, China. The intervention and data collection took place in June 2023. The teacher received training and practiced the play before the intervention for students. The participants were second-grade students, averaging eight years of age, from two classes totaling 72 students (28 girls and 44 boys). Data from two participants were excluded from this study because of their absence due to illness during the intervention period. Participants in this study are described in

Table 1.

The research was conducted with permission obtained from the school administration, the teachers involved, and students’ parents. All students and their parents were informed about the voluntary nature of participation in the activities and answering questions, confidentiality measures, and their right to withdraw at any time. All personal information of participants was anonymized to ensure confidentiality.

Qualitative data from students were collected through discussions, reflections, written assignments, and interviews. Students’ discussions and reflections on the activity were guided by questions such as: (1) What were your feelings about undertaking this activity? (2) What did you learn? (3) Did you notice any changes in yourself or in your class? (4) Did you encounter any difficulties? These discussions and reflections were voice-recorded and subsequently transcribed.

Additional qualitative data were gathered from observations and interviews with teachers. Two class teachers who were responsible for these classes participated in this study. The interview for the teachers included the following questions: (1) What were your observations while students were playing the activity? (2) What did you notice the students have learned? (3) What changes did you observe in the students and in the class later? (4) What difficulties or challenges did you encounter in facilitating the activity? (5) Is there anything else you would like to share? The teachers’ interview data were voice recorded and transcribed.

Table 2 lists the intervention and data collection timeline and process.

2.2. Description of “Curious About Others” Play

In this study, the “Curious about others” play was used as an intervention. The “Curious about others” play activity consisted of three parts:

Students can choose to practice and apply the activity at home by interviewing their parents, grandparents, siblings, neighbors, or anyone they want to know more about, using the same types of questions mentioned above.

After a week of practice, each student needs to write a learning diary, reflecting on their experience. They share their learning experiences by answering the following questions. Alternatively, teachers can gather all the students in the class to discuss these reflective questions together.

How did I feel about this activity?

What did I learn from this activity?

What changes have I noticed in myself?

In the past week, when did I use the skill of being curious about others?

Did I encounter any difficulties while playing this activity?

2.3. Research Method and Data Analysis

In this study, we applied the qualitative content analysis research method. Content analysis is a systematic research method used to make valid inferences from data within its context, aiming to provide knowledge, new insights, a representation of facts, and practical guidelines for action (

Krippendorff, 1980). It allows researchers to structure their analysis while retaining flexibility to explore complex phenomena. However, one challenge is that researchers may interpret data through their own subjective perspectives (

Sandelowski, 1995). As

Creswell et al. (

2007) noted, qualitative researchers approach their work with specific worldviews shaped by a set of beliefs or assumptions.

In this study, we had a diverse and experienced team of Finnish-, Chinese-, and English-speaking researchers. We were mindful of our cultural backgrounds and aimed to remain aware of these influences while analyzing the study context. Ensuring trustworthiness is crucial in qualitative content analysis, achieved through strategies such as credibility, dependability, and confirmability (

Elo et al., 2014). Trustworthiness relies on the availability of rich, relevant, and well-saturated data (

Elo et al., 2014), making the alignment of data collection, analysis, and reporting essential.

Improving the trustworthiness of content analysis starts with thorough preparation, requiring advanced skills in data gathering, analysis, and reporting (

Sklare, 2005). In this study, we ensured trustworthiness through detailed preparation before the study, careful data collection, collaboration with experienced researchers, and detailed descriptions of participants and the research process. By adhering to these practices, we maintained a rigorous and trustworthy approach throughout this research process.

We utilized Atlas.ti version 23 software for the qualitative data analysis in this study. We imported the qualitative data in the form of textual documents into the software for systematic examination. The analysis was carried out by a team of four experienced researchers. Initially, two researchers independently conducted coding of the data. Following the independent coding phase, the two researchers compared their findings and collaboratively refined their analysis with input from the other two researchers. This iterative process ensured inter-coder reliability and consensus on the coding framework. Subsequently, the team engaged in discussions to synthesize insights and facilitate data interpretation. The analysis provided a foundation for addressing the research questions (RQs) and revealed the findings.

To address RQ1, we employed a deductive content analysis approach to identify codes corresponding to four key elements (referred to as categories) of social skills. For instance, terms related to the communication skills category, such as “listening” and “expressing oneself,” were coded accordingly.

Table 3 outlines the qualitative data analysis process using deductive content analysis. The analysis focused on four primary categories associated with social skills: communication, cooperation, empathy, and self-control.

For RQ2, where no pre-established categories were available, we employed an inductive content analysis approach. This method allowed us to explore and identify the challenges students encountered during the activity without predefined categories. The inductive approach enabled an open exploration of the data to identify emerging categories related to the challenges.

Table 4 illustrates the qualitative data analysis process used for addressing RQ2 through inductive content analysis.

3. Results

In this section, we present the findings aligned with the research questions proposed in this study, structured as follows: (1) students’ learning outcomes related to social skills and (2) challenges encountered by the students.

3.1. Students’ Learning Outcomes Related to Social Skills

In this section, we present the findings to answer the first part of RQ1 regarding students’ perceptions of their learning related to social skills resulting from the play activity. A deductive approach was used to analyze the qualitative data. The data indicated that through participating in this activity, students advanced their social skills. Students reported gaining valuable skills and making personal advancements in the following areas: (1) communication; (2) cooperation; (3) empathy; and (4) self-control.

3.1.1. Improved Ability to Communication with Others

Our data showed that the “Curious About Others” play based on an SFA can enhance students’ communication skills, focusing on their listening, self-expression, and concentration abilities. Students reported learning to listen actively and understand others better. This was echoed by teachers, who observed increased attentiveness and focused listening during lessons. Students gained confidence in articulating their thoughts and engaging in meaningful dialogue, including asking and answering questions effectively. Both students and teachers noted improvements in concentration during interactions, allowing for deeper engagement and understanding. This is supported by the student and teacher data, which are listed in

Table 5. Improvements in active listening and expressive abilities likely contribute to stronger interpersonal relationships and better engagement. Teachers’ observations of heightened attentiveness corroborate students’ self-reports, indicating that these gains are noticeable and impactful in classroom settings.

3.1.2. Strengthened Ability to Cooperate

The data reflect students’ strengthened ability to cooperate, as evidenced by both the student and the teacher data. The findings revealed improvements in students’ group work, collaboration, and overall teamwork. Students reported feeling encouraged and supported by their classmates, which boosted their confidence and willingness to offer reciprocal support. There was a noticeable increase in mutual support and helpfulness within the class. Students highlighted the collaborative nature of their group work, noting that they collectively addressed difficulties and improved as a team. The activity facilitated the development of new friendships, enhanced understanding of peers’ strengths, and contributed to a supportive classroom environment. Teachers also observed improved teamwork and a positive classroom atmosphere because of the activity. This is supported by the student and teacher data listed in

Table 6. These findings underscore the value of this kind of activity in strengthening students’ cooperative skills and fostering a supportive and collaborative classroom environment.

3.1.3. Increased Empathy and Appreciation Among Students

The data revealed increased empathy and appreciation among students in students’ caring and expressing kindness. Students learned to offer kind words, praise others, and celebrate their peers’ strengths. These actions fostered positive emotions and mutual appreciation. Students acknowledged and valued individual differences, seeing the unique strengths in their peers. Through increased understanding and appreciation, students built stronger friendships and a sense of closeness with their peers. Students experienced boosts in self-esteem as they felt recognized and appreciated by their peers, improving their confidence and happiness. This is supported by the student data, which are listed in

Table 7. The findings suggest that the “Curious About Others” play based on an SFA promoted empathy and appreciation which can enhance the social and emotional dynamics among students. Praising and recognizing the strengths of others foster positive emotions, deeper connections, and trust among peers. This process not only strengthens interpersonal relationships but also cultivates a supportive community where individuals feel valued and respected.

3.1.4. Enhanced Ability in Students’ Self-Control

The data indicated notable enhanced ability in students’ self-control, particularly in the areas of turn-taking, attentiveness, and focus. Students demonstrated increased patience by waiting for their turn to speak during class discussions, with tools like the “talking pen” serving as an effective aid. There was increased attentiveness in the class. Both students and teachers noted better focus during lessons, including active listening and reduced interruptions. Teachers also reported improved classroom dynamics, with students displaying greater self-regulation and attentiveness. This is supported by the student and teacher data listed in

Table 8. The findings highlighted the importance of structured tools and practices, like the “talking pen,” in fostering self-control among students. These strategies encourage behavioral regulation, such as waiting for turns and being attentive, which are crucial for productive learning environments and better classroom management.

3.1.5. Summary of the Students’ Social Skills Development

In summary, evidence from both the student and teacher data demonstrates that the students enhanced their social skills across communication, cooperation, empathy, and self-control through engaging in this educational play. Students improved in listening, expressing themselves, and focusing during interactions. Both students and teachers reported heightened attentiveness and confidence in dialogue, fostering stronger relationships and engagement. Teamwork flourished, with students providing mutual support and addressing challenges collaboratively. Teachers observed a positive classroom atmosphere with better collaboration and reduced conflicts. Students developed kindness, learned to value peers’ strengths, and built stronger friendships. This fostered trust, positive emotions, and self-confidence through peer validation. Students demonstrated improved turn-taking, attentiveness, and behavioral regulation, aided by structured tools like the “talking pen.” Teachers noted better focus and classroom management.

These findings from the student data were confirmed by the teachers’ interview data. The primary responsible teacher confirmed these observations, noting the values of the “Curious About Others” play in fostering students’ social skills, particularly in the areas of communication, cooperation, empathy, and self-control with listening and waiting for their turn to speak, fostering better relationships among students, and increasing collaboration and support with fewer conflicts in her class. She remarked:

“Although this play looks very simple, it has brought great joy and learning to everyone. And I have noticed that listening is more important than telling. Learning to listen can bring each other closer together. To learn to listen, the first step is to focus and concentrate on listening, to give the other person a positive expression, to listen without evaluation or judgment, and to learn to ask good questions. Students have learned a lot from this simple game. Students are better now at waiting for their turn to speak and listening to others.”

She further added:

“Students have changed a lot after engaging in this activity. Classroom management has become smoother, with students displaying increased concentration and attentive listening when I speak. Notably, the students look happier, and conflicts have decreased, leading to improved adherence to classroom rules.”

3.2. Challenges and Solutions

To address RQ2, we investigated the challenges students faced during the activity. While the challenges were generally minor, they provided valuable learning experiences and opportunities for personal growth. We used an inductive approach for data analysis.

First, students faced difficulties with self-expression. Several students struggled with presenting themselves clearly in conversation, deciding whether to answer certain questions, and overcoming shyness. They learned to handle these situations by asserting themselves and by using phrases like “Pass, next question, please” when uncomfortable. Overcoming shyness and fear of judgment helped students become braver and contributed to building self-confidence.

Second, compliance with game rules posed a challenge. Some groups encountered issues with adherence to rules, particularly regarding turn-taking. Certain students dominated conversations, limiting opportunities for others to participate and highlighting the need for better rule compliance.

Third, there were challenges related to managing time and making decisions in prioritizing hobbies. Students struggled with discussing multiple hobbies within the allotted time, requiring them to make thoughtful decisions and prioritize their sharing.

Overall, the educational activity presented minor challenges, including a lack of self-expression skills, overcoming shyness, adhering to rules, managing time, and decision-making. These challenges served as valuable learning opportunities, promoting the development of better communication skills, cooperation, empathy, and self-control.

Table 9 presents the students’ challenges and ways to address them.

4. Discussion

This study explored students’ perception of their learning outcomes resulting from engaging in “Curious About Others,” the aim of which was to develop students’ social skills within the context of Chinese schools. The findings from this study reveal positive advancements in students’ social skills across communication, cooperation, empathy, and self-control. In this discussion, we interpret these findings within the framework of existing literature and theoretical perspectives.

Our results indicated that the “Curious About Others” play enhanced students’ social skills across main areas of communication, cooperation, empathy, and self-control. These results are consistent with the literature on social skills, which emphasizes the importance of key development areas in social skills (

Grover et al., 2020;

Little et al., 2017). Students demonstrated an improved ability to articulate their thoughts, engage in active listening, and participate in meaningful dialogues. This aligns with previous research indicating that structured play and educational activities can facilitate the development of such skills (

Niu et al., 2022). The activity also promoted interpersonal relationship-building and collaborative behaviors. Additionally, the increased ability to manage and resolve conflicts observed in this study further underscores the effectiveness of the intervention in fostering good relationships among students and promoting the importance of psychological safety in a learning environment (

Edmondson, 1999).

The design of the “Curious About Others” intervention incorporated various pedagogical and theoretical approaches, such as an SFA, playful learning, active and collaborative learning with Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory (

Vygotsky, 1978), and psychological safety (

Edmondson, 1999). The findings of the study are aligned with the essential elements in these theoretical frameworks. The results provided evidence of the value of the SFA in educational settings. SFA’s emphasis on strengths and positive behaviors (

Quick, 2008;

Lipchik, 2011;

Nicholas, 2014;

Sklare et al., 2003) aligns well with the observed improvements in students’ social skills. Its focus on positive changes can lead to developmental outcomes (

Cepukiene & Pakrosnis, 2011). Psychological safety, promoted through strategies like equitable expression and positive feedback, contributed to a supportive learning environment (

Niu, 2021). Furthermore, our findings are aligned with Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory (

Vygotsky, 1978), which emphasizes the role of social interactions and language in cognitive development. The play’s design, which encouraged interaction and collaboration, reflects Vygotsky’s perspective on the importance of social contexts in learning (

Vygotsky, 1978). The results and their theoretical alignments suggest that fostering positive social interactions through structured playful-related activities can significantly enhance students’ social skills.

While the study revealed several benefits, it also identified some challenges. Some students experienced difficulties with self-expression, including articulating their thoughts clearly, overcoming shyness, and managing fear of judgment. Additionally, adherence to rules and constraints related to limited time posed minor obstacles. The results of the challenges experienced by the students are important knowledge for teachers and parents. Learning self-expression skills, including articulating their thoughts clearly, overcoming shyness, and managing fear of judgment, needs time, and students often need many kinds of support. One way to help students can be this kind of play, in which students can have positive experiences in a psychologically safe environment. However, other supportive methods are also needed.

The findings of this study contribute to the growing body of evidence on the value of playful learning in enhancing social skills in educational settings. The “Curious About Others” play, grounded in multiple theoretical frameworks, promoted students’ social skills with relationship building, communication, cooperation, empathy, self-control, and conflict resolution between students. This intervention proved to be a valuable tool in supporting students’ social and emotional development. Future research should explore further refinements to the play and its application across diverse educational contexts to increase its value in students’ social skills development.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to investigate students’ perceptions of how the “Curious About Others” play enhances their social interactions. The study used a qualitative research method and included students’ written documents, learning reflection discussion recordings, as well as interviews with teachers and students. The findings indicate that this educational activity improved students’ social skills with the ability to communicate, cooperate, empathize, and self-control.

The students’ enhanced social skills highlight the potential benefits of integrating playful learning methods into educational practices. The results align with sociocultural theory, which emphasizes the role of social interaction in cognitive and emotional development (

Van Oers, 2010). The enhancement of social skills underscores the values of strength-based approaches, as supported by previous research (

Niu & Niemi, 2020;

Niu et al., 2022). This research provides practical implications for educators seeking to foster positive social interactions and create a supportive learning environment.

Based on these findings, educators are encouraged to incorporate playful learning activities that promote social skills with an SFA into their curricula. Such interventions can boost student communication, cooperation, empathy, and self-control, and improve social interactions. Additionally, school policies should consider integrating playful and strength-based SFA approaches into broader social–emotional learning frameworks.

However, it is important to acknowledge the study’s limitations. The sample size was relatively small and specific to a particular educational context, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data could have introduced response biases. The intervention period was also relatively short, indicating a need for longitudinal studies to fully assess the effectiveness of the intervention. Future research should address these limitations by employing larger, more diverse samples, incorporating objective measures, and conducting longitudinal studies.

Future research could explore the long-term impact of the “Curious About Others” play on students’ social skills and their overall well-being. Investigating the effectiveness of similar interventions in diverse educational contexts and cultural settings could provide a broader understanding of their applicability. Additionally, examining the impact of such interventions on other aspects of social and emotional development, and students’ well-being would be valuable.

In conclusion, this study underscores the potential of playful learning interventions with the SFA in fostering essential social skills among students. By demonstrating the benefits of the “Curious About Others” play, this research contributes to the growing body of knowledge on educational practices and offers practical recommendations for enhancing the development of students’ social and emotional competencies in the classroom.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.J.N., J.Y., J.W. and F.L.; methodology, validation, formal analysis: S.J.N., J.Y., J.W., H.W., J.L. and H.N.; investigation, resources, data curation: S.J.N., J.Y., J.W. and F.L.; writing—original draft preparation: S.J.N., H.N., J.Y. and J.W.; writing—review and editing: S.J.N., H.N., J.Y., J.W., H.W. and J.L.; visualization: S.J.N., H.N., J.Y., J.W., H.W. and J.L.; supervision: S.J.N., H.N. and J.W.; project administration: S.J.N., J.Y., J.W. and F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this study, we followed the research guidelines of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (TENK guidelines 2019). Ethical principles were discussed and considered in this study. In our research projects, ethical aspects were considered in the research context, data collection, and data management. An institutional review board statement is not needed in this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We express our thanks to Ben Furman for providing his solution-focused “Cruise about others” play intervention. And we thank the teachers and students who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ajmal, Y. (2001). Introducing solution-focused thinking. In Y. Ajmal, & I. Rees (Eds.), Solutions in schools: Creative applications of solution-focused brief thinking with young people and adults (pp. 10–29). BT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S., & Sked, H. (2010). The development of solution-focused multi-agency meetings in a psychological service. Educational Psychology in Practice, 26(3), 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P. (2008). Towards a developmental model of executive function. In V. Anderson, R. Jacobs, & P. Anderson (Eds.), Executive functions and the frontal lobes: A lifespan perspective (pp. 3–22). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Andreopoulou, P., & Moustakas, L. (2019). Playful learning and skills improvement. Open Journal for Educational Research, 3(1), 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, E. F., Cross, K. P., & Major, C. H. (2005). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, M. H., & Anderson, V. (2010). SOCIAL: An integrative framework for the development of social skills. Psychological Bulletin, 136(1), 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodrova, E. (2008). Make-believe play versus academic skills: A Vygotskian approach to today’s dilemma of early childhood education. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 16(3), 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, C., Woods, K., Humphrey, N., Symes, W., & Green, L. (2013). Practitioner review: The effectiveness of solution focused brief therapy with children and families: A systematic and critical evaluation of the literature from 1990–2010. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 54(7), 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T. (2002). Social neuroscience: Understanding the pieces fosters understanding the whole and vice versa. American Psychologist, 57(11), 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmeli, A., & Gittell, J. H. (2009). High-quality relationships, psychological safety, and learning from failures in work organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(6), 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepukiene, V., & Pakrosnis, R. (2011). The outcome of solution-focused brief therapy among foster care adolescents: The changes of behavior and perceived somatic and cognitive difficulties. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(6), 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., Hanson, W. E., Clark Plano, V. L., & Morales, A. (2007). Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(2), 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, P., & Berg, I. K. (2002). Interviewing for solutions. Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- De Shazer, S. (1985). Keys to solution in brief therapy. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- De Shazer, S. (1988). Clues: Investigating solutions in brief therapy. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Dockett, S. (2010). The challenge of play for early childhood education. In S. Rogers (Ed.), Rethinking play and pedagogy in early childhood education: Concepts, contexts, and cultures (pp. 32–48). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Driessen, E. P., Knight, J. K., Smith, M. K., & Ballen, C. J. (2020). Demystifying the meaning of active learning in postsecondary biology education. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 19(4), ar52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, A. (2007). The intentional teacher: Choosing the best strategies for young children’s learning. National Association for the Education of Young Children. [Google Scholar]

- Fleer, M. (2008). A cultural-historical perspective on play: Play as a leading activity across cultural communities. In I. Pramling-Samuelsson, & M. Fleer (Eds.), Play and learning in early childhood settings (pp. 1–17). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S., McDonough, M., Smith, M., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(23), 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, B. (2024). Ratkaisuja koulutyön haasteisiin. Viisas Elämä. [Google Scholar]

- George, E., Iveson, C., & Ratner, H. (1999). Problem to solution: Brief therapy with individuals and families. Brief Therapy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (2008). Social skills improvement system—Rating scales (SSIS-RS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, R. L., Nangle, D. W., Buffie, M., & Andrews, L. A. (2020). Defining social skills. In D. W. Nangle, C. A. Erdley, & R. A. Schwartz-Mette (Eds.), Social skills across the life span: Theory, assessment, and intervention (pp. 3–24). Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkarainen, P. (2006). Learning and development in play. In J. Einarsdottir, & J. T. Wagner (Eds.), Nordic childhoods and early education: Philosophy, research, policy, and practice in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden (pp. 183–222). Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Holzman, L. (2009). Vygotsky at work and play. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hyvönen, P. T. (2011). Play in the school context? The perspectives of Finnish teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(8), 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. S., & Franklin, C. (2009). Solution–focused brief therapy in schools: A review of the outcome literature. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(4), 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. S., & Kelly, M. S. (2008). Solution-focused brief therapy in schools. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kozanitis, A., & Nenciovici, L. (2023). Effect of active learning versus traditional lecturing on the learning achievement of college students in humanities and social sciences: A meta-analysis. Higher Education, 86(6), 1377–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Landa, R. J. (2005). Assessment of social communication skills in preschoolers. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 11(3), 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipchik, E. (2011). Beyond technique in solution focused therapy: Working with emotions and the therapeutic relationship. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Little, S. G., Swangler, J., & Akin-Little, A. (2017). Defining social skills. In J. Matson (Ed.), Handbook of social behavior and skills in children (pp. 9–17). Autism and Child Psychopathology Series. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, J., & Bateman, J. (2011). Working with children and teenagers using solution-focused approaches: Enabling children to overcome challenges and achieve their potential. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J. J. (2008). Best practices in conducting brief counseling with students. In A. Thomas, & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 1439–1456). National Association of School Psychologists. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, A. (2014). Solution-focused brief therapy with children who stutter. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 193(C), 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S. J. (2021). Teaching and learning 21st century competencies: Paving the way to the future [Doctoral dissertation, University of Helsinki]. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10138/333263 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Niu, S. J., & Niemi, H. (2020). Teachers support of students’ social-emotional and self-management skills using a solution-focused skillful-class method. The European Journal of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 27(1), 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S. J., Niemi, H., & Furman, B. (2022). Supporting K-12 students to learn social-emotional and self-management skills for their sustainable growth with the solution-focused kids’ skills method. Sustainability, 14(13), 7947. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/13/7947. [CrossRef]

- Quick, E. K. (2008). Doing what works in brief therapy: A strategic solution focused approach (2nd ed.). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Redpath, R., & Harper, M. (1999). Becoming solution-focused. Educational Psychology in Practice, 15(2), 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, J. (1993). The use of solution-focused brief therapy in schools. Educational Psychology in Practice, 9(1), 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L. (2009). Playful learning. Journal for Education in the Built Environment, 4(2), 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, Y. S., Ahn, J.-W., Kim, E., & Kim, J. (2018). Effects of prebriefing on psychological safety and learning outcomes. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 25, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. (1995). Qualitative analysis: What it is and how to begin. Research in Nursing & Health, 18(4), 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R. K. (2006). Educating for innovation. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 1(1), 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklare, G. B. (2005). Brief counseling that works: A solution-focused approach for school counselors and administrators (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sklare, G. B., Sabella, R. A., & Petrosko, J. M. (2003). A preliminary study of the effects of group solution-focused guided imagery on recurring individual problems. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 28(4), 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobie, I., Boyle, J., & Woolfson, L. (2005). Solution-focused approaches in the practice of UK educational psychologists: A study of the nature of their application and evidence of their effectiveness. School Psychology International, 26(1), 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oers, B. (2010). Children’s enculturation through play. In L. Brooker, & S. Edwards (Eds.), Engaging play (pp. 195–209). Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, F., & Schiemann, P. (2020). Assessing biology pre-service teachers’ professional vision of teaching scientific inquiry. Educational Sciences, 10(1), 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, T. (2012). Working with children and teenagers using solution-focused approaches: Enabling children to overcome challenges and achieve their potential. Child Care in Practice, 18(3), 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C., Carnell, E., & Lodge, C. (2007). Effective learning in classrooms. Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, N. (2018). Playful learning: Tools, techniques, and tactics. Research in Learning Technology, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).