Analyzing Barriers to Mentee Activity in a School-Based Talent Mentoring Program: A Mixed-Method Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Mentoring in the Context of Talent Development

1.2. Mentoring Programs for Talented Youth: Insights and Opportunities

1.3. General Considerations About Ensuring Effectiveness in School-Based Talent Mentoring

2. The Learning Pathway Mentoring Program

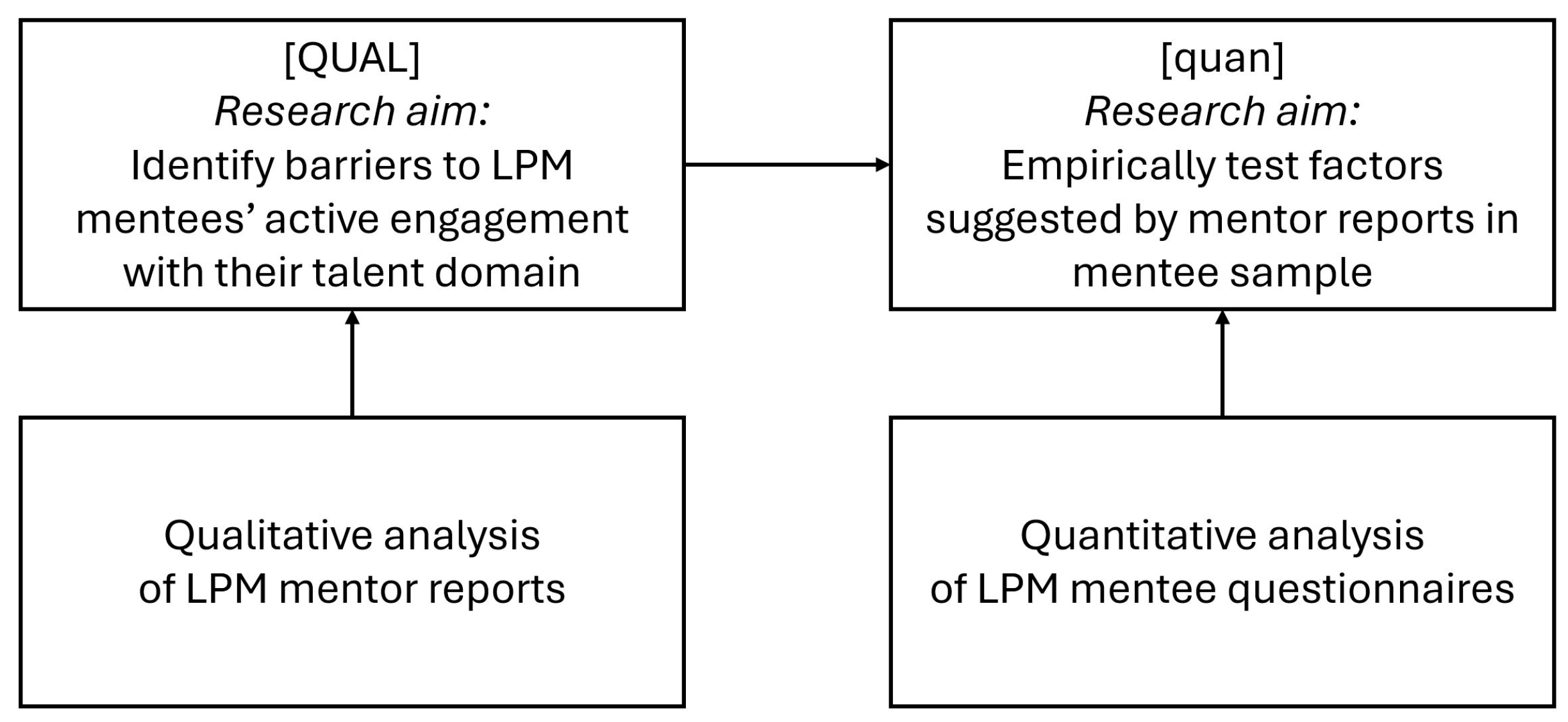

3. Current Study

Which barriers to mentees’ active engagement within their talent domains do teachers report who serve as mentors in a school-based talent mentoring program?

4. Qualitative Study

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Sample and Procedure

4.1.2. Measures

4.1.3. Qualitative Text Analysis

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Themes and Frequencies

4.2.2. Typology Investigation

5. Quantitative Study

- Is there a positive correlation between the priority mentees assign to their talent domain (domain priority) and the time they invest in talent domain activities (domain time investment)?

- Do changes in the priority mentees assign to their talent domain (domain priority) over the course of the mentoring program predict the extent of mentees’ talent domain activities (domain activity) after two years of mentoring?

- Do changes in mentees’ interest for their talent domain (domain interest) over the course of the mentoring program predict the extent of mentees’ talent domain activities (domain activity) after two years of mentoring?

- 4.

- Do mentee–mentor contact interruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic negatively predict the extent of mentees’ talent domain activities (domain activity) after two years of mentoring?

5.1. Method

5.1.1. Procedure

5.1.2. Sample

5.1.3. Measures

5.1.4. Analysis

5.2. Results

5.2.1. Descriptive

5.2.2. Predicting Domain Activity After Two Years of Mentoring

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary of Findings

6.2. Recommendations for Talent Development Mentoring

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions

6.4. Conclusions

- (1)

- In line with extant mentoring research in the context of academic or workplace mentoring, LPM mentors see a low commitment of mentees to activities and insufficient ability to work independently as a barrier to the successful implementation of activities and projects, impeding engagement and mentoring success.

- (2)

- In the context of a school-based talent mentoring program aimed at enhancing competence in a domain, LPM mentors expect mentees to sufficiently prioritize mentoring activities.

- (3)

- More importantly, LPM mentors specifically judge a diffusion of interests and subjective priorities in their mentees as strongly impedimental to the successful implementation of mentoring activities.

- (4)

- Findings of our auxiliary quantitative analysis of LPM mentee data suggest that the priority of mentoring subject may be a stronger predictor of mentee activity after two years of mentoring than overall GPA or interest in the subject domain.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asendorpf, J. B., van de Schoot, R., Denissen, J. J. A., & Hutteman, R. (2014). Reducing bias due to systematic attrition in longitudinal studies: The benefits of multiple imputation. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(5), 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J. L., Mazerolle, S. M., & Nottingham, S. L. (2017). Attributes of effective mentoring relationships for novice faculty members: Perspectives of mentors and mentees. Athletic Training Education Journal, 12(2), 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, A., Grossman, J. B., & DuBois, D. L. (2015). Using volunteer mentors to improve the academic outcomes of underserved students: The role of relationships. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(4), 408–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B. S. (Ed.). (1985). Developing talent in young people (1st ed.). Ballentine Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bonneville-Roussy, A., & Bouffard, T. (2015). When quantity is not enough: Disentangling the roles of practice time, self-regulation and deliberate practice in musical achievement. Psychology of Music, 43(5), 686–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. S., Rhodes, J. E., Howard, W. J., Lowe, S. R., Schwartz, S. E. O., & Herrera, C. (2013). Pathways of influence in school-based mentoring: The mediating role of parent and teacher relationships. Journal of School Psychology, 51(1), 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Elliot, A. J., & Sheldon, K. M. (2019). Psychological need support as a predictor of intrinsic and external motivation: The mediational role of achievement goals. Educational Psychology, 39(8), 1090–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. P., & Wong, J. (2013). Career counseling for gifted students. Australian Journal of Career Development, 22(3), 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K. M., Hagler, M. A., Stams, G.-J., Raposa, E. B., Burton, S., & Rhodes, J. E. (2020). Non-specific versus targeted approaches to youth mentoring: A follow-up meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(5), 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, L. J., Micko, K. J., & Cross, T. L. (2015). Twenty-five years of research on the lived experience of being gifted in school: Capturing the students’ voices. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 38(4), 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J. T., Gregus, S. J., Burton, A., Hernandez Rodriguez, J., Blue, M., Faith, M. A., & Cavell, T. A. (2016). Exploring change processes in school-based mentoring for bullied children. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 37(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J., Plano Clark, V. L., Gutmann, M., & Hanson, W. (2003). Advance mixed methods research designs. In A. Tashakkori, & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (pp. 209–240). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, D. Y. (2020). Assessing and accessing high human potential: A brief history of giftedness and what it means to school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 57(10), 1514–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debatin, T., Hopp, M. D. S., Vialle, W., & Ziegler, A. (2023). The meta-analyses of deliberate practice underestimate the effect size because they neglect the core characteristic of individualization—An analysis and empirical evidence. Current Psychology, 42(13), 10815–10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, M., Stewart, J., & van Gorder, K. (2015). Using methodological triangulation to examine the effectiveness of a mentoring program for online instructors. Distance Education, 36(3), 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, D. L., Holloway, B. E., Valentine, J. C., & Cooper, H. (2002). Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30(2), 157–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, D. L., Portillo, N., Rhodes, J. E., Silverthorn, N., & Valentine, J. C. (2011). How effective are mentoring programs for youth? A systematic assessment of the evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest: A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 12(2), 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durik, A. M., Vida, M., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Task values and ability beliefs as predictors of high school literacy choices: A developmental analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(2), 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L. T., Allen, T. D., Evans, S. C., Ng, T., & DuBois, D. (2008). Does mentoring matter? A multidisciplinary meta-analysis comparing mentored and non-mentored individuals. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(2), 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L. T., Allen, T. D., Hoffman, B. J., Baranik, L. E., Sauer, J. B., Baldwin, S., Morrison, M. A., Kinkade, K. M., Maher, C. P., Curtis, S., & Evans, S. C. (2013). An interdisciplinary meta-analysis of the potential antecedents, correlates, and consequences of protégé perceptions of mentoring. Psychological Bulletin, 139(2), 441–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elledge, L. C., Cavell, T. A., Ogle, N. T., & Newgent, R. A. (2010). School-based mentoring as selective prevention for bullied children: A preliminary test. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(3), 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerick, L. J. (1992). Academic underachievement among the gifted: Students’ perceptions of factors that reverse the pattern. Gifted Child Quarterly, 36(3), 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C. K. (2017). Multiple imputation as a flexible tool for missing data handling in clinical research. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 98, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericsson, K. A., & Harwell, K. W. (2019). Deliberate practice and proposed limits on the effects of practice on the acquisition of expert performance: Why the original definition matters and recommendations for future research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R., Perényi, Á., & Birdthistle, N. (2018). The positive relationship between flipped and blended learning and student engagement, performance and satisfaction. Active Learning in Higher Education, 22(2), 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. (1998). A proposal for subcategories within gifted or talented populations. Gifted Child Quarterly, 42(2), 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. (2010). Motivation within the DMGT 2.0 framework. High Ability Studies, 21(2), 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. (2015). Academic talent development programs: A best practices model. Asia Pacific Education Review, 16(2), 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R. (2014). Antecedents of mentoring support: A meta-analysis of individual, relational, and structural or organizational factors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(3), 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassinger, R., Porath, M., & Ziegler, A. (2010). Mentoring the gifted: A conceptual analysis. High Ability Studies, 21(1), 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, J. B., Chan, C. S., Schwartz, S. E. O., & Rhodes, J. E. (2012). The test of time in school-based mentoring: The role of relationship duration and re-matching on academic outcomes. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49(1–2), 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, J. B., & Rhodes, J. E. (2002). The test of time: Predictors and effects of duration in youth mentoring relationships. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30(2), 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hairon, S., Loh, S. H., Lim, S. P., Govindani, S. N., Tan, J. K. T., & Tay, E. C. J. (2020). Structured mentoring: Principles for effective mentoring. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 19(2), 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlin, R. G., & Sage, L. (2011). Behavioural criteria of perceived mentoring effectiveness. Journal of European Industrial Training, 35(8), 752–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbronner, N. N. (2011). Stepping onto the STEM pathway: Factors affecting talented students’ declaration of STEM majors in college. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 34(6), 876–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, C., Grossman, J. B., Kauh, T. J., & McMaken, J. (2011). Mentoring in schools: An impact study of Big Brothers Big Sisters school-based mentoring. Child Development, 82(1), 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, C., & Karcher, M. J. (2014). School-based mentoring. In D. L. DuBois, & M. Karcher (Eds.), Handbook of youth mentoring (pp. 203–220). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, T. P., & Olenchak, F. R. (2000). Mentors for gifted underachieving males: Developing potential and realizing promise. Gifted Child Quarterly, 44(3), 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablon, E. M., & Lyons, M. D. (2021). Dyadic report of relationship quality in school-based mentoring: Effects on academic and behavioral outcomes. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(2), 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvin, L., & Subotnik, R. F. (2010). Wisdom from conservatory faculty: Insights on success in classical music rerformance. Roeper Review, 32(2), 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S., & Park, S. (2020). Mentoring in the human resource development context. In B. J. Irby, J. N. Boswell, L. J. Searby, F. Kochan, R. Garza, & N. Abdelrahman (Eds.), The Wiley international handbook of mentoring (pp. 45–63). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchewa, S. S., Christensen, K. M., Poon, C. Y., Parnes, M., & Schwartz, S. (2021). More than fun and games? Understanding the role of school-based mentor-mentee match activity profiles in relationship processes and outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchewa, S. S., Yoviene, L. A., Schwartz, S. E. O., Herrera, C., & Rhodes, J. E. (2018). Relational experiences in school-based mentoring. Youth & Society, 50(8), 1078–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcher, M. J. (2008). The study of mentoring in the learning environment (SMILE): A randomized evaluation of the effectiveness of school-based mentoring. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 9(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karcher, M. J., Nakkula, M. J., & Harris, J. (2005). Developmental mentoring match characteristics: Correspondence between mentors’ and mentees’ assessments of relationship quality. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 26(2), 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, T. E., Collier, P. J., Blakeslee, J. E., Logan, K., McCracken, K., & Morris, C. (2014). Early career mentoring for translational researchers: Mentee perspectives on challenges and issues. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 26(3), 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, T. E., & Pryce, J. M. (2012). Different roles and different results: How activity orientations correspond to relationship quality and student outcomes in school-based mentoring. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 33(1), 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiewra, K. A., Luo, L., & Flanigan, A. E. (2021). Educational psychology early career award winners: How did they do It? Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1981–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of enrichment programs on gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 60(2), 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupersmidt, J. B., Stump, K. N., Stelter, R. L., & Rhodes, J. E. (2017). Predictors of premature match closure in youth mentoring relationships. American Journal of Community Psychology, 59(1–2), 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laco, D., & Johnson, W. (2019). “I expect it to be great… But will it be?” An investigation of outcomes, processes, and mediators of a school-based mentoring program. Youth & Society, 51(7), 934–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M. H. C., & Kwok, O. (2015). Examining the rule of thumb of not using multilevel modeling: The “Design Effect Smaller Than Two” rule. The Journal of Experimental Education, 83(3), 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, R. N., & Reschly, A. L. (2013). Reexamining gifted underachievement and dropout through the lens of student engagement. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 36(2), 220–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H., Cui, Y., & Zhou, W. (2018). Relationships between student engagement and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 46(3), 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, A. M., Goodloe, C. L., Johnson, H. E., & Deutsch, N. L. (2019). Understanding mutuality: Unpacking relational processes in youth mentoring relationships. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(1), 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (1993). The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment: Confirmation from meta-analysis. American Psychologist, 48(12), 1181–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, C. A., Kearney, K. L., & Britner, P. A. (2010). Students’ self-concept and perceptions of mentoring relationships in a summer mentorship program for talented adolescents. Roeper Review, 32(3), 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, D. F. (2009). Identifying academically talented students: Some general principles, two specific procedures. In L. V. Shavinina (Ed.), International handbook on giftedness (pp. 971–997). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdtke, O., Robitzsch, A., & Grund, S. (2017). Multiple imputation of missing data in multilevel designs: A comparison of different strategies. Psychological Methods, 22(1), 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M. D., McQuillin, S. D., & Henderson, L. J. (2019). Finding the sweet spot: Investigating the effects of relationship closeness and instrumental activities in school-based mentoring. American Journal of Community Psychology, 63(1-2), 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadov, S., & Topçu, A. (2014). The role of e-mentoring in mathematically gifted students’ academic life: A case study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 37(3), 220–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J., Rosário, P., Cunha, J., Carlos Núñez, J., Vallejo, G., & Moreira, T. (2024). How to help students in their transition to middle school? Effectiveness of a school-based group mentoring program promoting students’ engagement, self-regulation, and goal setting. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 76, 102230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathison, S. (1988). Why triangulate? Educational Researcher, 17(2), 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, B., Daunicht, T.-M., Emmerdinger, K., Stöger, H., & Ziegler, A. (2024). Das Mentoring-Programm “Individuelle Lernpfade” [The mentoring program “Individual learning pathways”]. In C. Fischer, F. Käpnick, C. Perleth, F. Preckel, M. Vock, H.-W. Wollersheim, & G. Weigand (Eds.), Wege der begabungsförderung in schule und unterricht: Transformative impulse aus wissenschaft und praxis (pp. 139–150). wbv Publikation. [Google Scholar]

- McQuillin, S. D., & Lyons, M. D. (2021). A national study of mentoring program characteristics and premature match closure: The role of program training and ongoing support. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 22(3), 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, J. C., Rosário, P., Vallejo, G., & González-Pienda, J. A. (2013). A longitudinal assessment of the effectiveness of a school-based mentoring program in middle school. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(1), 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, S. J., Choe, S. M. M., Otto, W. J., & Rahman, Z. (2018). Learning about the lives and early experiences of notable Asian American women: Productive giftedness, childhood traits, and supportive conditions. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 41(2), 160–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, K. M., & Plucker, J. A. (2004). Two steps forward, one step back: Effect size reporting in gifted education research from 1995–2000. Roeper Review, 26(2), 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D. W., Nicholson, L. J., Pekrun, R., Becker, S., & Symes, W. (2019). Expectancy of success, attainment value, engagement, and achievement: A moderated mediation analysis. Learning and Instruction, 60, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarda, A.-K., Matthes, B., Emmerdinger, K., Stoeger, H., & Ziegler, A. (2023). Individuelle Lernpfade. Ein schulbasiertes 1:1-Mentoring-Programm zur Förderung leistungsstarker und besonders motivierter Schülerinnen und Schüler [Individual learning pathways: A school-based one-on-one mentoring program to support high-performing and highly motivated students]. In C. Fischer, C. Fischer-Ontrup, F. Käpnick, N. Neuber, & C. Reintjes (Eds.), Potenziale erkennen—Talente entwickeln—Bildung nachhaltig gestalten: Beiträge aus der begabungsförderung (pp. 199–209). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Raposa, E. B., Rhodes, J., Stams, G. J. J. M., Card, N., Burton, S., Schwartz, S., Sykes, L. A. Y., Kanchewa, S., Kupersmidt, J., & Hussain, S. (2019). The effects of youth mentoring programs: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(3), 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Roche, G. R. (1979). Much ado about mentors. Harvard Business Review, 57(1), 14–20. Available online: https://hbr.org/1979/01/much-ado-about-mentors (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Schick, H., & Phillipson, S. N. (2009). Learning motivation and performance excellence in adolescents with high intellectual potential: What really matters? High Ability Studies, 20(1), 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M., & Preckel, F. (2017). Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 143(6), 565–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes, F., & Alarcao, M. (2014). Promoting well-being in school-based mentoring through basic psychological needs support: Does it really count? Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(2), 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. K., & Wood, S. M. (2020). Supporting the career development of gifted students: New role and function for school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 57(10), 1558–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R. (2006). Understanding the mentoring process between adolescents and adults. Youth & Society, 37(3), 287–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbergen-Hu, S., Makel, M. C., & Olszewski-Kubilius, P. (2016). What one hundred years of research says about the effects of ability grouping and acceleration on K–12 students’ academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 849–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmayr, R., & Spinath, B. (2009). The importance of motivation as a predictor of school achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 19(1), 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R. J. (2001). Giftedness as developing expertise: A theory of the interface between high abilities and achieved excellence. High Ability Studies, 12(2), 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J., Stoll, O., Pescheck, E., & Otto, K. (2008). Perfectionism and achievement goals in athletes: Relations with approach and avoidance orientations in mastery and performance goals. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 9(2), 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeger, H., Balestrini, D. P., & Ziegler, A. (2018). International perspectives and trends in research on giftedness and talent development. In S. I. Pfeiffer, E. Shaunessy-Dedrick, & M. Foley-Nicpon (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology. Apa handbook of giftedness and talent (1st ed., pp. 25–37). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeger, H., Debatin, T., Heilemann, M., & Ziegler, A. (2019). Online mentoring for talented girls in STEM: The role of relationship quality and changes in learning environments in explaining mentoring success. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2019(168), 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeger, H., Emmerdinger, K., & Ziegler, A. (2021). Teilprojekt 21: Individualisierung durch Mentoring: Praktische Umsetzung und Erforschung verschiedener Konzepte im schulischen Kontext [Subproject 21: Individualization through mentoring: Practical implementation and exploration of various concepts in a school context]. In C. Fischer, G. Weigand, F. Preckel, F. Käpnick, M. Vock, C. Perleth, & H.-W. Wollersheim (Eds.), Hochbegabung und pädagogische praxis. Leistung macht schule: Förderung leistungsstarker und potenziell besonders leistungsfähiger Schülerinnen und Schüler (pp. 213–223). Beltz Juventa. [Google Scholar]

- Stoeger, H., Hopp, M., & Ziegler, A. (2017). Online mentoring as an extracurricular measure to encourage talented girls in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics): An empirical study of one-on-one versus group mentoring. Gifted Child Quarterly, 61(3), 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeger, H., Luo, L., & Ziegler, A. (2024). Attracting and developing STEMM talent toward excellence and innovation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1533(1), 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeger, H., Schirner, S., Laemmle, L., Obergriesser, S., Heilemann, M., & Ziegler, A. (2016). A contextual perspective on talented female participants and their development in extracurricular STEM programs. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1377(1), 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeger, H., & Ziegler, A. (2008). Evaluation of a classroom based training to improve self-regulation in time management tasks during homework activities with fourth graders. Metacognition and Learning, 3(3), 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, S. E., Johnson, M. O., Marquez, C., & Feldman, M. D. (2013). Characteristics of successful and failed mentoring relationships: A qualitative study across two academic health centers. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 88(1), 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subotnik, R. F., Edmiston, A. M., Cook, L., & Ross, M. D. (2010). Mentoring for talent development, creativity, social skills, and insider knowledge: The APA catalyst program. Journal of Advanced Academics, 21(4), 714–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., Khalid, M., & Finster, H. (2021a). A developmental view of mentoring talented students in academic and nonacademic domains. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1483(1), 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. C. (2011). Rethinking giftedness and gifted education: A proposed direction forward based on psychological science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(1), 3–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. C. (2019a). High performance: The central psychological mechanism for talent development. In R. F. Subotnik, F. C. Worrell, & P. Olszewski-Kubilius (Eds.), The psychology of high performance: Developing human potential into domain-specific talent (pp. 7–20). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. C. (2021b). The talent development megamodel: A domain-specific conceptual framework based on the psychology of high performance. In R. J. Sternberg, & D. Ambrose (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness and talent (pp. 425–442). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotnik, R. F., Worrell, F. C., & Olszewski-Kubilius, P. (Eds.). (2019b). The psychology of high performance: Developing human potential into domain-specific talent. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Z. W., & Black, V. G. (2018). Talking to the mentees: Exploring mentee dispositions prior to the mentoring relationship. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 7(4), 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, C. H.-H., Kofinas, A. K., Trivedi, S. K., & Yang, Y. (2020). Overcoming the novelty effect in online gamified learning systems: An empirical evaluation of student engagement and performance. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 36(2), 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S. F., Cardinal, L. B., & Burton, R. M. (2017). Research design for mixed methods. Organizational Research Methods, 20(2), 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R. L., Kemp, C. R., Hodge, K. A., & Bowes, J. M. (2012). Searching for evidence-based practice. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 35(2), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S., & Mayo-Wilson, E. (2012). School-based mentoring for adolescents. Research on Social Work Practice, 22(3), 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B., & Salmela, J. H. (2010). Examination of practice activities related to the acquisition of elite performance in Canadian middle distance running. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 41, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, A. (2005). The actiotope model of giftedness. In R. J. Sternberg, & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 411–436). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A., Daunicht, T.-M., Quarda, A.-K., Emmerdinger, K., & Stoeger, H. (2022). Das Lernpfadkonzept: Theoretischer Hintergrund und zentrale Konzepte [The Learning Pathway concept: Theoretical background and central concepts]. In G. Weigand, C. Fischer, F. Käpnick, C. Perleth, F. Preckel, M. Vock, & H.-W. Wollersheim (Eds.), Leistung macht schule: Band 2. Dimensionen der begabungs- und begabtenförderung in der schule (381–396). wbv Publikation. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, A., Gryc, K. L., Hopp, M. D. S., & Stoeger, H. (2021). Spaces of possibilities: A theoretical analysis of mentoring from a regulatory perspective. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1483(1), 174–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zierer, K. (2021). Effects of pandemic-related school closures on pupils’ performance and learning in selected countries: A rapid review. Education Sciences, 11(6), 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Description | Sample |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | Collection of answers in mentor reports to the following: (a) Activities: Where did you encounter difficulties? (b) Where did you encounter difficulties in communication and cooperation [between you and your mentee]? (c) How have the available resources changed throughout the course of mentoring? | N = 57 mentor reports |

| (2) | Descriptive data analysis of word count in mentor replies. | N = 57 mentor reports |

| (3) | Two coders mark all missing, neutral, and positive statements across all three questions, e.g., (a) “activities have not concluded yet”; (b) “none; there were no difficulties in communication, the cooperation was excellent; reliable, dependable”; (c) “no change”. | N = 57 mentor reports |

| (4) | Removal of all cases lacking any report of difficulties (n = 11). | N = 46 mentor reports |

| (5) | Sample description by gender (mentor, mentee) and mentoring subject based on matched pre-mentoring nomination questionnaires. | N = 46 mentor reports |

| (6) | Aggregation of answers reporting difficulties across questions per case. | N = 46 mentor reports |

| (7) | Isolation of text segments for coding. Example: k1: Corona, k2: contact only via telephone/online, k3: little time of mentee, k4: due to other hobbies/interests. | N = 46 mentor report K = 129 text segments |

| (8) | The main author applies inductive in vivo coding over several iterations, identifying ten recurring categories (0–9). | N = 46 mentor reports K = 129 text segments C = 10 categories |

| (9) | The main author develops a codebook with explanations and a test coding sheet with fictitious text samples for the training unit (45 min). | NT = 4 KT = 17 |

| (10) | Coding of text segments by two trained independent coders (Krippendorff’s alpha = .81). Inconsistencies (k = 25) are discussed with the main author and jointly recoded. | N = 46 mentor reports K = 129 text segments C = 10 categories |

| (11) | Frequency count of categories per text segments (k) and over mentor reports (n). | N = 46 mentor reports K = 129 text segments C = 10 categories |

| (12) | Iterative typology classification on core themes of mentoring problems by frequency and source (mentee, relational, and contextual). | N = 46 mentor reports T = 9 types |

| Domain | Mentor | Mentee | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Female | Male | n | Female | Male | % | |

| Mathematics | 16 | 6 | 10 | 16 | 5 | 11 | 34.78 |

| German | 11 | 8 | 3 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 23.91 |

| Biology | 6 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 13.04 |

| History | 7 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 17.39 |

| Physics | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4.35 |

| Technics | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2.17 |

| Geography | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2.17 |

| English | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2.17 |

| N | 45 | 25 | 20 | 46 | 26 | 20 | |

| % | 55.56 | 44.44 | 56.52 | 43.48 | 100 | ||

| Category | Description | k | n | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Mentee’s inconsistent motivation and interest(s) | 20 | 19 | ‘sustaining motivation for work’; ‘due to other hobbies/interests’ |

| (2) | Mentee’s insufficient willingness or ability to invest time | 13 | 12 | ‘time expenditure was too high for her’; ‘mentee has little time’ |

| (3) | Mentee’s low commitment to tasks, goals, or agreements | 13 | 9 | ‘continuity and effort’; ‘non-binding nature of some agreements on the student’s side’ |

| (4) | Mentee’s low initiative | 14 | 11 | ‘many ideas/suggestions came from the mentor, not mentee’; ‘no or low initiative of mentee’ |

| (5) | Mentee’s inability to work autonomously | 6 | 6 | ‘there were difficulties regarding the independent implementation by mentee’; ‘practical implementation was often difficult for him’ |

| (6) | Mentee–mentor interaction (quality) | 7 | 7 | ‘video conferences too impersonal’; ‘contact only via telephone/online’ |

| (7) | Mentee–mentor interaction (quantity) | 10 | 10 | ‘frequent changes in the lesson plan, fixed scheduling not possible’; ‘meetings were partly irregular’ |

| (8) | Problems choosing appropriate goals and activities | 13 | 9 | ‘objective was […] not sufficiently clear’; ‘short-term goals were often too difficult’ |

| (9) | COVID-19 pandemic | 25 | 24 | ‘especially during lockdown’; ‘due to Corona’ |

| (0) | Statements relating to resources | 8 | 6 | ‘technical resources were lacking’; ‘general conditions and the social components have changed due to the [mentee’s] illness’ |

| Types | Core Theme | n | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mentee | |||

| (1a) | Inconsistent motivation | 11 | ‘intermittently questionable motivation’; ‘long-term motivation’ |

| (1b) | Inconsistent interest in domain subject | 2 | ‘he lost interest in the subject a little’; ‘mentee has shifted her field of interest from biology to computer science’ |

| (2) | Time constraints | 6 | ‘already 5–6 h of lessons online daily’; ‘high workload in senior classes’ |

| (2 + 1b) | Time constraints due to concurrent interests | 5 | ‘little time of mentee due to other hobbies/interests’; ‘Student does not invest a sufficient amount of time. Has lots of additional projects (music).’ |

| (2 + 1a) | Time constraints and low motivation | 1 | ‘maintaining motivation to work’, ‘daily demands’ |

| (3, 4, 5) | Low self-direction, responsibility, commitment | 8 | ‘mentee has great difficulty with independent work organization, [she] rarely used the school platform’ |

| Relational | |||

| (6/7 + 9) | Inhibited interaction during lockdown | 6 | ‘meetings/appointments did not always work out due to corona conditions.’ |

| (8) | Unsuitable goals/activities | 3 | ‘finding suitable mid-term goals/topic areas that lead to the long-term goal’ |

| Contextual | |||

| (9) | Practical difficulties relating to the pandemic | 4 | ‘interviews with contemporary witnesses (over 80 years old) under the conditions of contact restrictions (“Corona”)’ |

| Sample | All Cases a (N = 82) | Dropouts (n = 34) | Study Sample (n = 48) | Independent Samples t-Test Results (Dropout vs. Study Sample) b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | t | p |

| Pre-mentoring | |||||

| Age | 13.15 (1.45) | 13.12 (1.53) | 13.17 (1.40) | 0.150 | .881 |

| GPA | 5.14 (0.65) | 5.05 (0.63) | 5.20 (0.66) | 1.027 | .308 |

| Domain activity | 4.32 (1.10) | 4.05 (1.28) | 4.50 (0.92) | 1.775 | .064 |

| Domain priority | 4.83 (1.01) | 4.53 (1.19) | 5.04 (0.81) | 2.173 | c .034 |

| Domain interest | 5.14 (0.68) | 4.87 (0.64) | 5.33 (0.65) | 3.175 | .002 |

| After two years | |||||

| Weekly hours invested in domain | 6.63 (3.48) | ||||

| GPA | 5.28 (0.69) | ||||

| Domain activity | 4.61 (0.87) | ||||

| Domain priority | 4.77 (0.87) | ||||

| Domain interest | 5.10 (0.69) | ||||

| Age 1 | GPA 1 | Domain Activity 1 | Domain Priority 1 | Domain Interest 1 | GPA 2 | Domain Activity 2 | Domain Priority 2 | Domain Interest 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPA 1 | r | −.03 | – | |||||||

| p | a .846 | |||||||||

| Domain | r | .23 | −.10 | – | ||||||

| activity 1 | p | .116 | a .521 | |||||||

| Domain | r | .23 | −.08 | .54 | – | |||||

| priority 1 | p | .116 | a .583 | <.001 | ||||||

| Domain | r | −.18 | −.02 | .33 | .30 | – | ||||

| interest 1 | p | .223 | a .895 | .022 | .036 | |||||

| GPA 2 | r | .05 | .73 | −.07 | −.01 | .02 | – | |||

| p | .754 | a <.001 | .652 | .955 | .874 | |||||

| Domain | r | .34 | −.08 | .52 | .44 | .31 | −.05 | – | ||

| activity 2 | p | .017 | a .593 | <.001 | .002 | .032 | .753 | |||

| Domain | r | .35 | −.16 | .23 | .42 | .31 | −.14 | .64 | – | |

| priority 2 | p | .016 | a .295 | .124 | .003 | .034 | .343 | <.001 | ||

| Domain | r | −.04 | .08 | .07 | .21 | .51 | −.02 | .31 | .59 | – |

| interest 2 | p | .772 | a .586 | .636 | .150 | <.001 | .901 | .030 | <.001 | |

| Domain | r | .16 | −.18 | .15 | .12 | .15 | −.11 | .35 | .51 | .24 |

| time 2 | p | b .303 | c .250 | b .328 | b .430 | b .308 | b .476 | b .017 | b <.001 | b .102 |

| Variable | b | 95% CI | SE | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.008 | [−1.899, 1.915] | 0.942 | 0.009 | .993 | |

| Domain activity 1 | 0.221 | [−0.047, 0.488] | 0.132 | 0.240 | 1.671 | .103 |

| Continuation during lockdown | 0.419 | [−0.013, 0.851] | 0.213 | 0.224 | 1.966 | .057 |

| Domain priority 1 | 0.692 | [0.307, 1.077] | 0.190 | 0.519 | 3.642 | <.001 |

| Domain priority CS | 0.412 | [0.077, 0.747] | 0.165 | 0.305 | 2.491 | .017 |

| Domain interest 1 | −0.018 | [−0.382, 0.346] | 0.180 | −0.014 | −0.099 | .922 |

| Domain interest CS | −0.164 | [−0.525, 0.189] | 0.179 | −0.124 | −0.918 | .364 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daunicht, T.-M.; Emmerdinger, K.J.; Stoeger, H.; Ziegler, A. Analyzing Barriers to Mentee Activity in a School-Based Talent Mentoring Program: A Mixed-Method Study. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020162

Daunicht T-M, Emmerdinger KJ, Stoeger H, Ziegler A. Analyzing Barriers to Mentee Activity in a School-Based Talent Mentoring Program: A Mixed-Method Study. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(2):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020162

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaunicht, Tina-Myrica, Kathrin Johanna Emmerdinger, Heidrun Stoeger, and Albert Ziegler. 2025. "Analyzing Barriers to Mentee Activity in a School-Based Talent Mentoring Program: A Mixed-Method Study" Education Sciences 15, no. 2: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020162

APA StyleDaunicht, T.-M., Emmerdinger, K. J., Stoeger, H., & Ziegler, A. (2025). Analyzing Barriers to Mentee Activity in a School-Based Talent Mentoring Program: A Mixed-Method Study. Education Sciences, 15(2), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020162