Diverging Paths: How German University Curricula Differ from Computing Education Guidelines

Abstract

1. Introduction

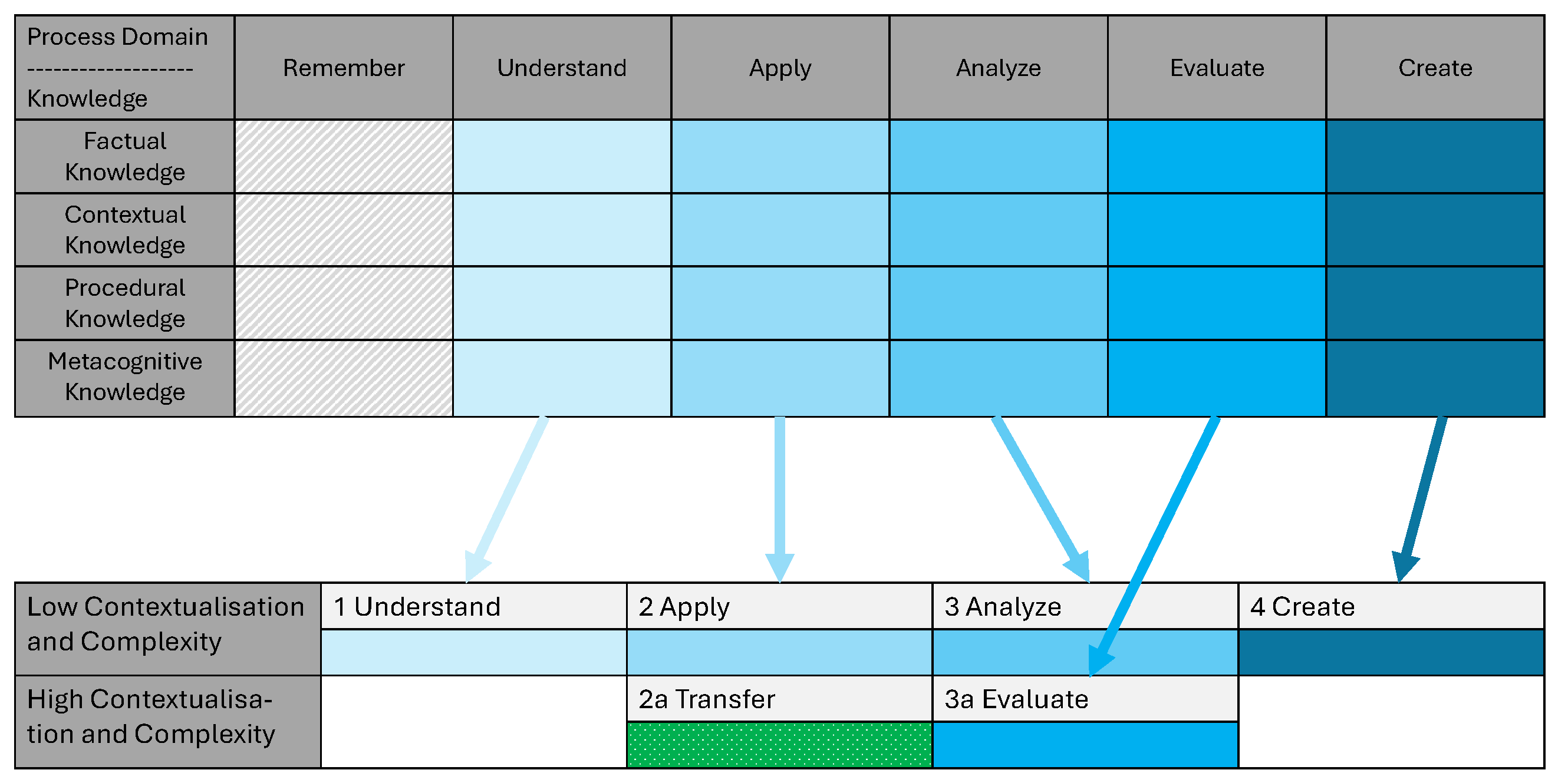

2. Theoretical Background

3. Method

- RQ1

- Which learning outcomes defined in the guidelines of the GI can still be found in teaching?

- RQ2

- Which learning outcomes defined in the guidelines of the GI can no longer be found in teaching?

- RQ3

- Which new learning outcomes are actually taught in higher education but are not yet addressed in the GI recommendations?

3.1. Literature Survey

3.2. Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA)

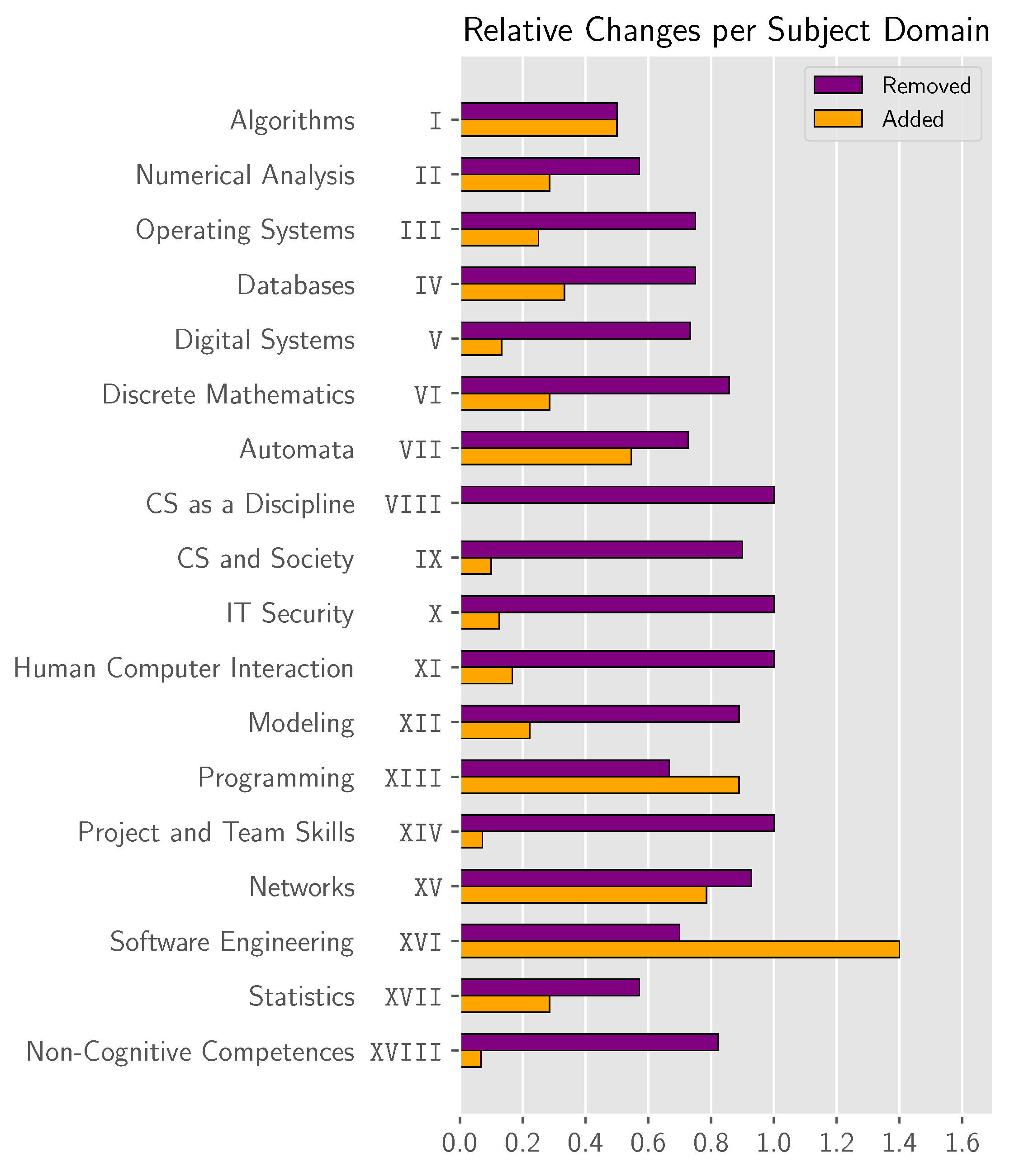

4. Primary (Quantitative) Findings

- Every subject area experienced removal of at least half of their defined competences;

- No competences of the subject areas VIII (Computer Science as a Discipline), X (IT Security), XI (Human Computer Interaction), and XIV (Project and Team Skills) remained; all were removed in accordance with the study criteria;

- Subject areas XIII (Programming Languages and Methods) and XVI (Software Engineering) experienced the most additions with about 90% and about 140%, respectively.

5. Secondary (Qualitative) Findings

5.1. No Learning Outcomes

5.1.1. Example 1

| English original: an introduction to [...] the programming of database applications is given. |

| — Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel (1-Fach)—infDB01a Database Systems |

| Students can write simple SELECT statements containing a FROM/WHERE clause. |

| Students can explain the difference between inner join, left join, right join, and outer join. |

| Students can write a JOIN statement using the optimal type of join. |

| Students can construct an optimized database view. |

5.1.2. Example 2

| German original: Festgelegte Schnittstellen mit bekannter Spezifikation liefern einen Teil der Daten für das eingebettete System und das System gibt ebenfalls Daten über normierte Schnittstellen heraus. |

| English translation: Interfaces with known specifications provide a part of the data for the embedded system and the system also sends data through standartized interfaces. |

| — HS Bremerhaven—Eingebettete Systeme |

5.1.3. Example 3

| German original: Simulation, Reduktion, Vollständigkeit |

| English translation: Simulation, Reduction, Completeness |

| — Uni Lübeck—CS2000 Theoretische Informatik |

| Students can use software programs to simulate the execution of different models. |

| Students can perform reduction to reduce a given problem to another given problem. |

| Students can prove the NP-completeness of a given problem. |

5.2. Unclear Learning Outcomes

5.2.1. Example 1

| English original: an introduction to [...] the programming of database applications is given. |

| — Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel (1-Fach)—infDB01a Database Systems |

| Know: Students can state the syntax of a SELECT statement. |

| Understand: Students can explain a given simple SELECT statement containing a FROM/WHERE clause. |

| Apply: Students can write simple SELECT statements containing a FROM/WHERE clause based on a textual description. |

5.2.2. Example 2

| German original: fachliche Kompetenzen: Die Studierenden lernen, wie Daten in relationalen Datenbanken abgelegt und verarbeitet werden |

| English translation: expertise: Students learn how data is saved and processed in relational databases |

| — HS Bremerhaven—Datenbanken 1 |

| German original: -Beherrschung elementarer Beweistechniken und Beweise selbst durchführen können. |

| English translation: -Master fundamental methods of proof and are able to do proofs themselves. |

| — Uni Bremen (Hauptfach)—THI 1 |

| German original: können mit Parametern, Transformationen und graphischen Darstellungen umgehen |

| English translation: being able to deal with parameters, transformations, and graphical representations |

| — HAW—Analysis und lineare Algebra |

| Remember: Students can describe how data is saved in relational databases. |

| Understand: Students can explain why data is saved in a given data type in a database. |

| Apply: Students can perform a SELECT statement on a given database. |

| Analyze: Students can compare different schemas for saving data in a database. |

| Evaluate: Students can argue whether a given schema is appropriate for given data. |

| Create: Students can create a schema for a set of given data. |

5.3. Lack of Context

5.3.1. Example 1

| German original: Vorgehen bei der Analyse und beim Entwurf von umfangreichen Systemen |

| English translation: Approach for the analysis and design of large systems. |

| — HSB—Softwaretechnik |

| XVI Software Engineering: Students can analyze whether a system follows given code quality standards. |

| XII Modeling: Students can analyze whether the behavior of a system fits the model of the system. |

5.3.2. Example 2

| German original: - Methodenwissen für die Analyse von Anwendungskontexten und die Gestaltung von Informatiksystemen. |

| English translation: - Method knowledge for the analysis of application contexts and the design of information systems |

| — Uni Hamburg—InfB-IKON Informatik im Kontext |

| Remembering: Students can enumerate over different methods for the analysis of application contexts and the design of information systems. |

| Procedural knowledge: Students can determine which method should be applied for a given analysis task of a given information system. |

| Procedural Analysis: Students are able to select and execute a fitting method to analyze application contexts. |

5.3.3. Example 3

| German original: entwerfen, implementieren und analysieren anhand von Anforderungen eigene Algorithmen, |

| English translation: design, implement and analyze own algorithms based on requirements |

| — BHH—Algorithmen und Datenstrukturen |

| Students can create own algorithms given a problem to solve and a target runtime in Landau-notation. |

| Students implement own algorithms given run time constraints of a real (physical) system. |

| Students can analyze whether a self-designed algorithm is correct given a formal specification. |

5.3.4. Example 4

| German original: Simulation, Reduktion, Vollständigkeit |

| English translation: Simulation, Reduction, Completeness |

| — Uni Lübeck—CS2000 Theoretische Informatik |

5.3.5. Example 5

| German original: Analyse der Betriebsmittelanforderungen in einer Mehrprozess-Umgebung |

| English translation: Analysis of resource requirements in a multicore environment |

| — HS Bremen (Dualer Studiengang Informatik)—Betriebssysteme |

| Students can analyze why a deadlock occurred in a multicore environment. |

| Students can analyze what conditions must be true in a given multicore environment for deadlock to occur. |

| Students can analyze which (and how many) resources are needed to execute a given task. |

5.3.6. Example 6

| German original: In Gruppen Probleme analysieren und gemeinsam Lösungsstrategien entwickeln und präsentieren können |

| English translation: Work in a group to analyze problems and collaboratively develop and present solutions35 |

| — Uni Bremen (Hauptfach)—Praktische Informatik 2, Technische Informatik 2, Informatik und Gesellschaft |

| Technical computer science 2: Students find problems in a given hardware-software-system. |

| Practical computer science 2: Students can rephrase a formal problem. Students can create a program that solves a formal problem. |

| Computer Science and Society: [no special learning outcome needed here] |

| Soft skills (separate section in all three modules): Students can work in a group. |

5.4. Separate Lists for Different Learning Outcomes

5.5. Further Findings

| German original: Sie kennen die Einfachheit und Eleganz der Konstruktion von Algorithmen durch das Weglassen von Programmvariablen, Zuweisungen und Schleifen. |

| English translation: They know the simplicity and elegance of constructing algorithms by foregoing variables, assignments and loops. |

| — FH Wedel—B010 Grundlagen der Funktionalen Programmierung |

| Students construct algorithms in the functional programming paradigm without using variables, assignments and loops. |

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion of Direct Coding Results (RQ1 and RQ2)

6.1.1. Incidence of Subject Domains

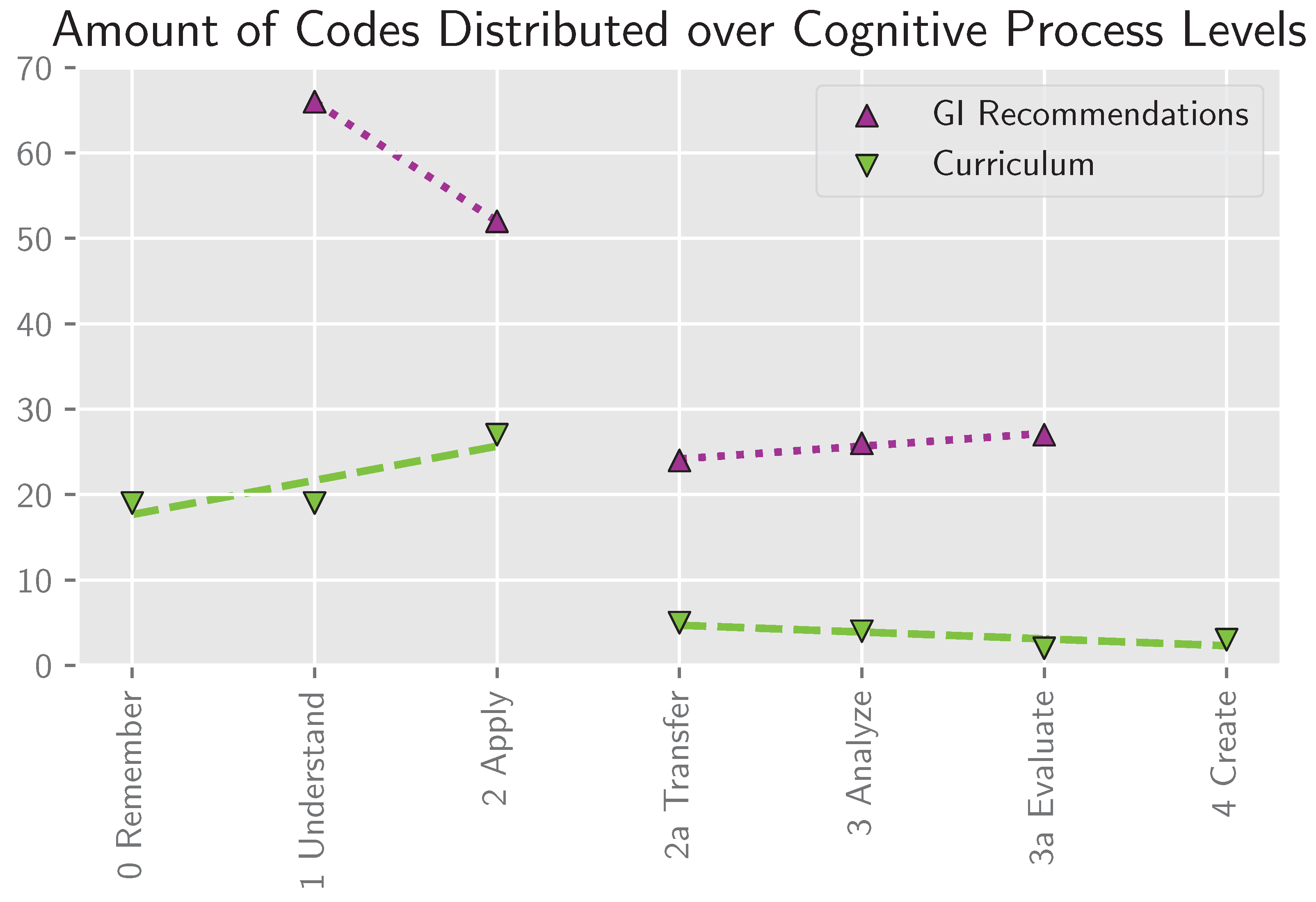

6.1.2. Checking for GI Model Assumptions

- Rote Remembering (without Understanding) has no relevance for one’s own field of expertise;

- Creating only happens in theses or large projects situated late in the study program, at least in the context of Bachelors’ degrees;

- Evaluation is only a context-specific special case of Analysis;

- Non-cognitive competencies can not be formulated as learning outcomes.

Thus, at least in the revised taxonomy (which the GI refers to), Creating refers to any process in which a problem is tackled by freely generating a solution space and then implementing a fitting solution38.Create […] also refers to objectives calling for production that all students can and will do. […] in meeting these objectives, many students will create in the sense of producing their own synthesis […] to form a new whole […]—Anderson et al. (2001, p. 85; text that was highlighted in italics in the source is underlined here.)

- There is a clear distinction between the two levels in both the original Bloom’s Taxonomy (e.g., see Bloom et al. (1956, p. 144, p. 185)39) as well as in the AKT (e.g., see Anderson et al. (2001, p. 68)). Any changes to the established theory should therefore be carefully explained. The GI gives as a reason that Analyze is a sine qua non for Evaluate40, which is in immediate contradiction to the AKT scheme they use (see Anderson et al. (2001, pp. 267–268), Krathwohl (2002, p. 215)). The only other reason is the GI claiming that high complexity and contextualization are mandatory for evaluation (Zukunft, 2016, p. 68), a claim they give no real explanation for. Imagine an exercise like “Evaluate whether a given pseudo code (e.g., list all permutations of a list with 20 elements) can be run in reasonable time on a common PC.”. This fulfills the definition of low context of the GI (level K2) but is clearly an evaluation task;

- Many learning outcomes by the GI are wrongly sorted based on their wording. For example, in IT Security, the learning outcome “X.3.a Question properties and limitations of security concepts, combine different concepts in a sensible manner, and evaluate the security of complex systems.” is sorted as Analyze while “X.3a.a Analyze situations in a company setting that pertain to IT security.” is sorted as Evaluate (highlights made by the authors of the paper).

6.2. New Learning Outcomes and Domains (RQ3)

6.3. A Note on the Quality of Learning Outcomes (Secondary Findings)

6.4. A Note on the GI Recommendations

| English original: understanding of the tasks, structure and functionality of an operating system |

| — CAU—1-Fach–infOS-01a Operating Systems |

| German original: können Softwaresysteme auf verschiedenen Abstraktionsebenen beschreiben |

| English translation: can describe software systems on different abstraction layers |

| — Uni Lübeck—CS2300-KP06 Software Engineering |

6.5. Limitations

6.5.1. Blind Spot: Electives and Study Specializations

6.5.2. Regional Selection Bias

6.5.3. Bias Caused by Syllabus Descriptions

6.5.4. Data Density

6.5.5. Single Coder

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKT | Anderson–Krathwohl Taxonomy |

| GI | Gesellschaft für Informatik, e.V. (German Computer Science Society) |

| RQ | Research Question |

| QCA | Qualitative Content Analysis |

| 1 | See https://ehea.info/, accessed on 10 November 2025. |

| 2 | See Ministerial Conference in Bologna (1999) for the original declaration. |

| 3 | https://acbsp.org/page/outcomes_assessment, accessed on 11 November 2025. |

| 4 | See https://gi.de/, accessed on 10 November 2025. |

| 5 | Originally, the Bloom working group postulated three different taxonomies with different areas (or domains) of application: The Cognitive domain, the Affective domain, and the Psychomotor domain. In current discourse, only the Cognitive domain receives much attention; while a definition for the Affective domain exists, most efforts for formal education focus on cognitive outcomes. The Psychomotor domain hadn’t even been defined by the original working group, although works from different authors that do define it exist (see Anderson et al. (2001, p. xxvii)). |

| 6 | In addition, the name might lean on the two notable works that present and describe the revision to the scientific and educational communities: Anderson et al. (2001) and Krathwohl (2002). |

| 7 | Sometimes, the revised model is used, but the newer knowledge domain is ignored, leading to learning outcomes whose wordings align with the process domain of the AKT (rather than the original Bloom taxonomy), e.g., by using Create instead of Synthesis, but are not sorted in the second dimension. |

| 8 | Calling back to the notion of hierarchy, most readers are probably familiar with the aforementioned “Bloom Pyramid”. This pyramid form cannot actually be found in the primary works on the taxonomy. Furthermore, for the revised model, the notion of the pyramid is indeed factually wrong since “[…] [in the revision] the requirement of a strict hierarchy has been relaxed to allow the categories to overlap one another.” (Krathwohl, 2002, p. 215). |

| 9 | Some examples are learning outcome, learning objective, competence, competency, mastery, outcome-based education vs. outcome-based teaching and learning, and outcome-based education vs. competency-based education. These terms are sometimes used interchangeably, although they appear to have slightly different meanings. For more discussion, see Hartel and Foegeding (2004), Harden (2002), Holmes et al. (2021); see also Nodine (2016, p. 10). Other examples may be content, curriculum and syllabus, which all denote some form of course or program description; course and program, which are both used to label an entire degree; or course and module, which both can be used to label a(n atomic) unit (or group of units) of learning. The label course is especially egregious: a course of study vs. a course on programming. |

| 10 | The GI model actually defines five levels of complexity and contextualization (Zukunft, 2016, p. 10): K1 no contextualization; K2 small examples; K3 more complex examples; K4 internal projects; and K5 company projects. However, in the actual competence matrix, the first two levels and the second two levels are combined, respectively, into the rows for “low” and “high” contextualization and complexity. The fifth level receives no further attention in the GI model. |

| 11 | In addition to K for complexity (Komplexität), the recommendations also define W for the type of knowledge according to Anderson et al. (2001) (Wissen) and T for the type of scientific work. Notably, T is not independent of the dimensions of cognitive processes, complexity (K), and type of knowledge (W) in the GI model. |

| 12 | The Joint Task Force on Computing Curricula Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) IEEE Computer Society (2013), which had been the current version during the time in which the current GI model had been designed. |

| 13 | An in-depth comparison would be a research project in itself and shall thus be omitted here. |

| 14 | |

| 15 | The non-cognitive competences are comparable to the Professional Practices of the CS2013 recommendations, although the Professional Practices are more thoroughly integrated in CS2013 (The Joint Task Force on Computing Curricula Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) IEEE Computer Society, 2013, pp. 15–16) up to being part of their own subject area, Social Issues and Professional Practice (The Joint Task Force on Computing Curricula Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) IEEE Computer Society, 2013, pp. 192–203). |

| 16 | See https://gi.de/ueber-uns, accessed on 17 July 2025, only available in German. |

| 17 | Representing all universities that offer study programs in computer science. |

| 18 | Representing all other higher education institutes that offer study programs in computer science. |

| 19 | https://www.asiin.de/en/home.html, accessed on 23 September 2025. |

| 20 | Internationally recognized might be the one by the ACM/IEEE/AAAI (Kumar et al., 2024) |

| 21 | Unfortunately, the accord does not define what computer science/computing actually is. It defines multiple professional levels (Seoul accord, 2008, Sec. D.2); however, they are defined as “Apply knowledge of computing fundamentals, knowledge of a computing specialization, and mathematics, science, and domain knowledge appropriate for the computing specialization…” (Seoul accord, 2008, D.2.3) and neither knowledge of computing fundamentals nor knowledge of a computing specialization are actually defined. Therefore, it is impossible to derive learning outcomes on a content level from it. |

| 22 | According to https://www.seoulaccord.org/signatories.php, accessed on 23 September 2025. A list of accreditation agencies that are officially recognized in Germany can be found at https://www.akkreditierungsrat.de/en/accreditation-system/agencies/agencies, accessed on 23 September 2025. |

| 23 | Available at https://web.arbeitsagentur.de/studiensuche/, accessed on 23 September 2025 (only available in German). |

| 24 | In German education, dual study or work-study programs combine an academic degree with related vocational training in a company. |

| 25 | In English, it is also known as Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. |

| 26 | Most universities in Germany offer areas where you can choose between different courses and sometimes even include courses from different disciplines. Since it is not clear if every graduate has gained the competences listed in these non-mandatory courses, we did not include them in the study. |

| 27 | While the study used the German book (Mayring, 2022) as a foundation, an English version also exists and is provided here as reference Mayring (2021). Note that the English version prescribes a strict eight-step process, which is only implied in the German version. |

| 28 | That is, math competences that could not be (clearly) assigned to one of the already defined math subject domains. These deal with, for example, proofs and formal notation, which are relevant for all fields of math. |

| 29 | Notable mentions for content are: types of companies, company structures, and the interaction between CS/ICT and business management. |

| 30 | Analogously to Note 7, General Computer Science describes topics and competences related to computer science that could not clearly be assigned to any single subject domain, such as general skills in handling computers, computational thinking, or tool skills like LATEX. |

| 31 | There could be an argument made about whether 2a Transfer, at least for the GI recommendations, should belong to the first or the second bin. The quality of the fit does not vary greatly. However, as it is immediately obvious where the border between bins for the curricula is situated, it was chosen to keep the models for both distributions within the same constraints. |

| 32 | For example, the Hamburg Law for Higher Education (Hamburgisches Hochschulgesetz) demands “die pädagogische Eignung für die Lehre an der Hochschule,” (HmbHG, 2025, § 15 (1) 2.) (translation: “the pedagogical qualification for teaching at an institute of higher education”). However, the qualification is only suggested to be certified by displaying relevant accomplishments during the Juniorprofessur (HmbHG, 2025, §15 (2)) (a Juniorprofessur is an assistant professor without tenure intended to learn the job of “professor” and qualify themselves for tenure positions instead of getting a traditional qualification through habilitation). This often amounts to having taught courses, not possessing any formal training. |

| 33 | For example, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel (1-Fach)—infDB01a Database Systems refers to the course “infDB01a Database Systems” as offered in the study program “1-Fach” at the institute “Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel”. |

| 34 | Since No Level is not desirable, it is not shown as an example. |

| 35 | Another perfectly valid translation might be “Work in a group to analyze problems, develop solutions together and use presentation methods.“—a translation suggested by a different author—which is further evidence for how unclear this learning outcome actually is, as it differs somewhat in how the group work is scoped: The first translation requires group presentations whereas the second does not. |

| 36 | Any personal positions of the authors notwithstanding, the authors do not want to make a claim concerning the importance of any one subject area over any other. |

| 37 | And in fact, Anderson et al. (2001, p. 34) mentioned that to clearly assign learning outcomes to a level, it is important to include other information such as observation of the classroom, analysis of assessment items, or the instructors’ intend. |

| 38 | Not unlike what “modern” vernacular refers to as Problem-Based Learning. |

| 39 | “Analysis emphasizes the breakdown of the material into its constituent parts and detection of the relationships of the parts and of the way they are organized.” (Bloom et al., 1956, p. 144) vs. “Evaluation is defined as the making of judgments about the value, for some purpose, of ideas, works, solutions, methods, material, etc.” (Bloom et al., 1956, p. 185) |

| 40 | The exact quote is “Da außerdem das Analysieren unabdingbare Voraussetzung für das Bewerten ist, […]” (Zukunft, 2016, p. 68), which translates to “Since Analysis is an indispensable requirement for Evaluation, […]” |

| 41 | Which combines economics, business administration, as well as computer science and is similar to “information systems” in English. For an example, see https://www.haw-hamburg.de/en/bachelor-business-information-systems/, accessed on 30 September 2025. |

| 42 | With the exception of XXI Artificial Intelligence, XXII Signal Processing, and ICIX General Maths, the new topics can be found in the ACM/IEEE/AAAI recommendations (Kumar et al., 2024) but are fringe topics subsumed under larger topics. |

| 43 | E.g., computer science at the University of Hamburg contains a module Seminar which is mandatory and teaches research methods; however, students can choose one from several different courses to fill that module. |

| 44 | On the other hand, one could argue that the coding actually represents the reality well and that those sections containing only keywords/chapters should be considered violating the outcome-based education approach. |

| 45 | For a hypothetical example, for databases it is mentioned that “Students perform queries on common database models”, and a specific database like MongoDB is (only) mentioned in the keywords of all universities; that discovery would have been a valuable insight for the question of the diverging paths. In this hypothetical scenario, the discovery could be that universities do not teach relational databases but all teach the same NoSQL database. |

| 46 | Strictly speaking, Anderson et al. (2001, see p. 34) does not speak of coders but of instructors having the task to classify teaching material. Therefore, Anderson et al. (2001) suggests not only looking at formal descriptions but also observing the course itself, looking at the examination, and talking to the instructors. Since this study—by design—only looked at the curricula, such an extensive approach was not possible |

References

- Agentur für Qualitätssicherung durch Akkreditierung von Studiengängen e. V. (2019). Gutachten zur Akkreditierung der Studiengänge · “Informatik“ (B.Sc.) · “Informatik“ (M.Sc.) · “Praktische Informatik“ (M.Sc.) an der FernUniversität in Hagen (No. 449-xx–3). Hannover. Available online: https://antrag.akkreditierungsrat.de/dokument/c73b8c84-5b9c-469a-9530-3fc6d9443165 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Allegre, C., Berlinguer, L., Blackstone, T., & Rüttgers, J. (1998). Sorbonne Joint Declaration. Joint declaration on harmonisation of the architecture of the European higher education system. Available online: https://ehea.info/media.ehea.info/file/1998_Sorbonne/61/2/1998_Sorbonne_Declaration_English_552612.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P. W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M. C. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (abridged edition). Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Annala, J., Lindén, J., & Mäkinen, M. (2015). Curriculum in higher education research. In J. M. Case, & J. Huisman (Eds.), Researching higher education—International perspectives on theory, policy and practice (pp. 171–189). Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASIIN e.V. (2018). Fachspezifisch ergänzende hinweise des fachausschusses 4—informatik zur akkreditierung von bachelor- und masterstudiengängen der informatik (verabschiedet: 29. März 2018). Available online: https://www.asiin.de/files/content/kriterien/ASIIN_FEH_04_Informatik_2018-03-29.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Aubel, I., Zug, S., Dietrich, A., Nau, J., Henke, K., Helbing, P., Streitferdt, D., Terkowsky, C., Boettcher, K., Ortelt, T. R., Schade, M., Kockmann, N., Haertel, T., Wilkesmann, U., Finck, M., Haase, J., Herrmann, F., Kobras, L., Meussen, B., … Versick, D. (2022). Adaptable Digital Labs - Motivation and Vision of the CrossLab Project. In 2022 IEEE German Education Conference (GeCon) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, T. (2022). Die Wirksamkeit von Lernzielen für Studienleistungen–eine experimentelle Studie. Die Hochschullehre, 8, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does (4th ed.). Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. handbook 1: Cognitive domain. McKay New York. [Google Scholar]

- Brahimi, T., Sarirete, A., & Ibrahim, R. M. (2016). The impact of accreditation on student learning outcomes. International Journal of Knowledge Society Research, 7(4), 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlier, J.-É., & Croché, S. (2007). The Bologna process: The outcome of competition between Europe and the USA and now a stimulus to this competition. European Education, 4, 10–26. Available online: https://dial.uclouvain.be/pr/boreal/en/object/boreal%3A180588/datastream/PDF_01/view (accessed on 11 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H. M. (1988). Organizing knowledge syntheses: A taxonomy of literature reviews. Knowledge in Society, 1(1), 104–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desel, J. (2017). Die Entwicklung neuer GI-empfehlungen für informatik-studiengänge. In INFORMATIK 2017 (pp. 235–240). Gesellschaft für Informatik. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, K. A. (1989). The association between student ratings of specific instructional dimensions and student achievement: Refining and extending the synthesis of data from multisection validity studies. Research in Higher Education, 30(6), 583–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foundation for International Business Administration Accreditation. (2023). Assessment guide for the accreditation of bachelor and master programmes by FIBAA. Available online: https://www.fibaa.org/fileadmin/redakteur/pdf/PROG/Handreichungen_und_Vorlagen/231006_AG_PROG_Bachelor_Master_en.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V. (2005). Empfehlungen für bachelor- und masterprogramme im studienfach informatik an hochschulen. Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V. Available online: https://dl.gi.de/bitstreams/dc7ba3f3-979d-46bf-b69b-7643ff715d55/download (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Hamburgisches Hochschulgesetz (HmbHG) Vom 18. Juli 2001 zuletzt geändert durch Gesetz vom 19. Februar 2025, HmbGVBl. S. 241. (2025). Available online: https://www.landesrecht-hamburg.de/bsha/document/jlr-HSchulGHArahmen (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Harden, R. M. (2002). Learning outcomes and instructional objectives: Is there a difference? Medical Teacher, 24(2), 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrow, A. J. (1972). A taxonomy of the psychomotor domain: A guide for developing behavioral objectives. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Hartel, R., & Foegeding, E. (2004). Learning: Objectives, competencies, or outcomes? Journal of Food Science Education, 3(4), 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, A. G. D., Tuin, M. P., & Turner, S. L. (2021). Competence and competency in higher education, simple terms yet with complex meanings: Theoretical and practical issues for university teachers and assessors implementing Competency-Based Education (CBE). Educational Process International Journal, 10(3), 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C. G., & Fuller, U. (2006). Is Bloom’s taxonomy appropriate for computer science? In Proceedings of the 6th baltic sea conference on computing education research: Koli calling 2006 (pp. 120–123). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D. (2006). Writing and using learning outcomes: A practical guide. University College Cork. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesler, N. (2020). Towards a competence model for the novice programmer using bloom’s revised taxonomy—An Empirical Approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 acm conference on innovation and technology in computer science education (pp. 459–465). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 212–218. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1477405 (accessed on 7 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Krathwohl, D. R., Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives, the classification of educational goals; handbook II: The afffective domain. Dacid KcMay. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A. N., Raj, R. K., Aly, S. G., Anderson, M. D., Becker, B. A., Blumenthal, R. L., Eaton, E., Epstein, S. L., Goldweber, M., Jalote, P., Lea, D., Oudshoorn, M., Pias, M., Reiser, S., Servin, C., Simha, R., Winters, T., & Xiang, Q. (2024). Computer science curricula 2023. Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar]

- Marzano, R. J. (1998). A theory-based meta-analysis of research on instruction. Mid-Continent Regional Educational Lab. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. (2021). Qualitative content analysis: A step-by-step guide. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. (2022). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken (13th ed.). BELTZ. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerial Conference in Berlin. (2003). “Realising the european higher education area”. Communiqué of the conference of ministers responsible for higher education in Berlin on 19 September 2003. Available online: https://ehea.info/media.ehea.info/file/2003_Berlin/28/4/2003_Berlin_Communique_English_577284.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Ministerial Conference in Bologna. (1999). The bologna declaration of 19 june 1999. Joint declaration of the european ministers of education. Available online: https://ehea.info/media.ehea.info/file/Ministerial_conferences/02/8/1999_Bologna_Declaration_English_553028.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Nodine, T. (2016). How did we get here? A brief history of competency-based higher education in the United States. The Journal of Competency-Based Education, 1(1), 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancratz, N., & Grave, V. (2023, September 13–14). “Informatik und gesellschaft” in der hochschullehre: Eine untersuchung von modulhandbüchern verschiedener informatikstudiengänge an norddeutschen universitäten. 10. Fachtatung Hochschuldidaktik Informatik (HDI 2023), Aachen, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul accord. (2008). Taipei. Available online: https://www.seoulaccord.org/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Simpson, B. J. (1966). The classification of educational objectives: Psychomotor domain. Illinois Journal of Home Economics, 10(4), 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tedre, M. (2011). Computing as a science: A survey of competing viewpoints. Minds and Machines, 21(3), 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joint Task Force on Computing Curricula Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) IEEE Computer Society. (2013). Computer science curricula 2013: Curriculum guidelines for undergraduate degree programs in computer science. ACM, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, R. W. (1949). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, R. W., & Hlebowitsh, P. S. (2013). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez-Iturbide, J. A. (2021). An analysis of the formal properties of bloom’s taxonomy and its implications for computing education. In Proceedings of the 21st koli calling international conference on computing education research (pp. 1–7). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentrale Evaluations- und Akkreditierungsagentur. (2018). Akkreditierungsbericht zum akkreditierungsantrag der FHDW hannover abteilung betriebswirtschaftslehre 449-xx-3 (No. 449-xx–3). Hannover. Available online: https://hub.zeva.org/AkkreditierteStudiengaengeAltesSchema/Downloads/Download/176 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Zukunft, O. (2016). Empfehlungen für bachelor- und masterprogramme im studienfach informatik an hochschulen (Juli 2016). Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V. Available online: https://dl.gi.de/handle/20.500.12116/2332 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

| Number | Subject Domain | No Level | Know | Understand | Apply | Transfer | Analyze | Evaluate | Create | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Algorithms and Data Structures | 241 | 43 | 58 | 36 | 23 | 35 | 19 | 10 | 465 |

| II | Numerical Analysis | 106 | 8 | 17 | 19 | 12 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 160 |

| III | Operating Systems | 151 | 4 | 41 | 14 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 236 |

| IV | Databases and Information Systems | 144 | 21 | 17 | 47 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 251 |

| V | Digital Logic, Digital Systems, Computer Architecture | 225 | 31 | 82 | 46 | 1 | 17 | 10 | 7 | 419 |

| VI | Discrete Structures, Logic, Algebra | 181 | 20 | 26 | 50 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 289 |

| VII | Formal Languages and Automata | 196 | 19 | 26 | 32 | 3 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 291 |

| VIII | Computer Science as a Discipline | 17 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 32 |

| IX | Computer Science and Society | 66 | 9 | 27 | 12 | 2 | 8 | 24 | 1 | 149 |

| X | IT Security | 52 | 15 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 83 |

| XI | Human Computer Interaction | 34 | 12 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 60 |

| XII | Modeling | 63 | 9 | 9 | 38 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 130 |

| XIII | Programming Languages and Methods | 305 | 57 | 46 | 120 | 10 | 14 | 6 | 8 | 566 |

| XIV | Project and Team Skills | 22 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 33 |

| XV | Computer Networks and Distributed Systems | 132 | 62 | 25 | 44 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 3 | 291 |

| XVI | Software Engineering | 209 | 43 | 28 | 76 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 9 | 390 |

| XVII | Probability Theory and Statistics | 118 | 11 | 8 | 21 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 172 |

| XVIII | Non-Cognitive Competences † | 408 | 408 | |||||||

| XIX | Data Science | 15 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 |

| XX | Business Administration | 53 | 21 | 30 | 21 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 137 |

| XXI | Artificial Intelligence | 20 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 36 |

| XXII | Signal Processing | 26 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 39 |

| XXIII | Research Methods | 12 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 44 |

| XXIV | Robotics | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| ICVIII | Computer Science (General) | 38 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43 |

| ICIX | Mathematics (General) | 41 | 7 | 40 | 52 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 162 |

| Total | 2878 | 414 | 508 | 674 | 112 | 131 | 139 | 67 | 4923 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kobras, L.; Soll, M.; Desel, J. Diverging Paths: How German University Curricula Differ from Computing Education Guidelines. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121694

Kobras L, Soll M, Desel J. Diverging Paths: How German University Curricula Differ from Computing Education Guidelines. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121694

Chicago/Turabian StyleKobras, Louis, Marcus Soll, and Jörg Desel. 2025. "Diverging Paths: How German University Curricula Differ from Computing Education Guidelines" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121694

APA StyleKobras, L., Soll, M., & Desel, J. (2025). Diverging Paths: How German University Curricula Differ from Computing Education Guidelines. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121694